Abstract

COVID-19 mortality disproportionally affects nursing homes, creating enormous pressures to deliver high-quality end-of-life care. Comprehensive palliative care should be an explicit part of both national and global COVID-19 response plans. Therefore, we aimed to identify, review, and compare national and international COVID-19 guidance for nursing homes concerning palliative care, issued by government bodies and professional associations. We performed a directed documentary and content analysis of newly developed or adapted COVID-19 guidance documents from across the world. Documents were collected via expert consultation and independently screened against prespecified eligibility criteria. We applied thematic analysis and narrative synthesis techniques. We identified 21 eligible documents covering both nursing homes and palliative care, from the World Health Organization (n = 3), and eight individual countries: U.S. (n = 7), The Netherlands (n = 2), Ireland (n = 1), U.K. (n = 3), Switzerland (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 1), and Belgium (n = 1). International documents focused primarily on infection prevention and control, including only a few sentences on palliative care–related topics. Palliative care themes most frequently mentioned across documents were end-of-life visits, advance care planning documentation, and clinical decision making toward the end of life (focusing on hospital transfers). There is a dearth of comprehensive international COVID-19 guidance on palliative care for nursing homes. Most have a limited focus both regarding breadth of topics and recommendations made. Key aspects of palliative care, that is, symptom management, staff education and support, referral to specialist services or hospice, and family support, need greater attention in future guidelines.

Key Words: COVID-19, nursing homes, long-term care, palliative care

Impact Statement

What this research specifically adds

-

•

This paper reports on the first directed documentary and content analysis of guidance documents from across the world concerning palliative care in nursing homes in the context of COVID-19. Findings can support future palliative care guidance development for COVID-19 in nursing homes, by highlighting unaddressed topics that require urgent attention.

-

•

Twenty-one documents (both international and country-specific) provided recommendations regarding palliative care in nursing homes in the context of COVID-19 (up until April 8, 2020), albeit mostly with a very limited focus (e.g. regulating visits for dying residents, hospitalizations at the end of life).

-

•

Key aspects of palliative care were largely unaddressed, including protocols for holistic assessment and management of symptoms and needs at the end of life (including stockpiling medications), education of staff concerning palliative care, referral to specialist palliative care or hospice, advance care planning communication, support for family including bereavement care, and support for staff.

Introduction

Nursing home residents, who are often frail and affected by multimorbidity, account for between 42% and 57% of all deaths related to COVID-19,1 , 2 although these data are unsystematically reported. The high mortality in nursing homes is likely due to the vulnerability of the population and the close physical proximity between residents and staff, as well as insufficient staff training and equipment for infection control.3 , 4

Although guidelines to support nursing homes in preventing and managing the current crisis are evolving rapidly across the world, there is urgent need specifically for clear guidance on end-of-life care for these settings.5 , 6 Palliative care has a key role in the care for older people affected by COVID-19.7 It is an approach that aims to improve people's quality of life and that of their families, facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness. It includes not only impeccable symptom management—including for respiratory distress—but also psychological, social, and spiritual care and support in medically and ethically difficult end-of-life decision making.8

We sought to inform the update and development of new guidelines by examining and synthesizing existing national and international COVID-19 guidance documents for nursing homes concerning palliative and/or end-of-life care, and by studying which specific recommendations they make.

Methods

We conducted a directed documentary and content analysis of guidance documents across the world concerning palliative care in nursing homes in the context of COVID-19.

Representatives of regional, national, or international networks with expertise in geriatrics, long-term care, or palliative care identified eligible guidance documents. In addition, government and professional associations' web sites were hand-searched. We collected data from March 25 to April 8, 2020. We included publicly available documents concerning COVID-19 that were specifically developed for or included a separate section on nursing homes (“long-term,” “aged,” “post-acute long-term,” “residential” care, “care homes,” or “care retirement communities”); included advice concerning palliative or end-of-life care, advance care planning (ACP), end-of-life decisions, or critically ill/terminal/end-stage patients; were endorsed by a representative body (i.e., association of health care professionals, governments); and written in English, German, French, or Dutch. Eligibility of documents was evaluated independently by J. G., L. P., and L. V. d. B. against inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement, decisions were discussed until consensus was reached. Excerpts were extracted by J. G. applying inductive bottom-up coding of common themes and performing content analysis using NVIVO (QSR) software. Initially coded themes (by J. G.) were discussed with L. P. and L. V. d. B., after which a final coding instruction was prepared by J. G. Final themes were reviewed and discussed by all authors to reach consensus. Results are reported using narrative synthesis techniques.

No ethics approval was required.

Results

Characteristics of Guidance Documents

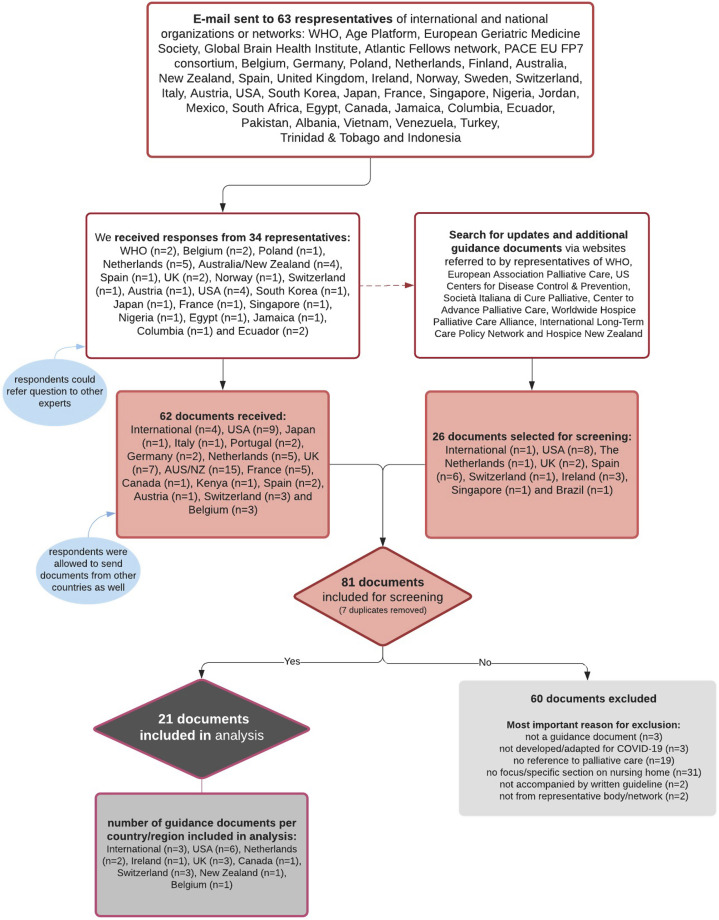

Of 81 identified guidance documents, 21 were eligible (Appendix Fig. 1), three being from the WHO, and eight from individual countries: United States (US, n = 7),9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 the Netherlands (NL, n = 2),16 , 17 Ireland (IE, n = 1),18 United Kingdom (UK, n = 3),19, 20, 21 Switzerland (CH, n = 3),22, 23, 24 New Zealand (NZ, n = 1),25 and Belgium (BE, n = 1)26 (Appendix Table 1).

Appendix Fig. 1.

Flowchart of data collection.

We identified five types of documents, based on the relative extent of their focus on nursing homes and/or palliative care:

-

1.

primary topic is palliative care specifically in nursing homes (n = 4 from CH, NL, and US).

-

2.

primary topic is nursing home care, with recommendations specifically for palliative care (n = 4, NL, CH, and BE).

-

3.

primary topic is palliative care, with recommendations specifically for nursing homes (n = 1, UK).

-

4.

primary topic is nursing home care, with limited focus on palliative care (n = 10, WHO, US, NZ, UK, and IE).

-

5.

cover one specific end-of-life care theme relevant for nursing homes, that is, dead body and funeral arrangements or symptom management in severe respiratory infection (n = 2, WHO).

Recommendations for Nursing Homes Concerning Palliative or End-of-Life Care

Across documents, nine general and eight palliative/end-of-life care–specific themes are addressed, often to a limited extent (Table 1 ). Documents provide guidance regarding restrictions to visits in end-of-life situations (n = 12 documents), ACP (n = 14), and clinical decision making regarding the appropriateness of hospital/ICU admissions (n = 11). The following end-of-life care themes are addressed in less than 10 documents: symptom management at the end of life (n = 8), need for specialist palliative care advice and involvement of palliative care teams (n = 7), preparations of the body and funeral arrangements (n = 4), and spiritual care (n = 3). One document mentions foreseeing stock of medication and a prescription chart to enable palliative care. Almost all lack practical and operational recommendations for staff or facility managers, that is, who should do what, and when. Documents, for example, indicate “plans should be made for palliative care” or “accompany relatives in coping with grief” without further explanation, referrals, or guidance.

Table 1.

General Themes and Palliative/End-of-Life Care Themes Identified in Guidance Documents (n = 21)

| Themes | Subthemes | Examples of Excerpts Underlying Theme (Source) | No. of Different Guidance Documents Covering Theme | No. of Excerpts Underlying Theme | Documents That Addressed Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Themes | |||||

| Theme 1: Preparation of the nursing home for COVID-19 outbreak (capacity for staffing, equipment, supplies) | “All care homes should have a business continuity policy in place including a plan for surge capacity for staffing, including volunteers”13 “RCF settings must have COVID-19 preparedness plans in place to include planning for cohorting of residents (COVID-19 separate from non-COVID-19), enhanced IPC, staff training, establishing surge capacity, promoting resident and family communication.”12 |

10 | 15 | 6; 7; 8; 10; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 20 | |

| Theme 2: Prevention, outbreak management, and control measures | 14 | 90 | |||

| 2.1. Preventive and control measures, including outbreak management in residents and staff | “Minimum precautions to reduce the general risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections: …”20 “Physical distancing in the facility should be instituted to reduce the spread of COVID-19”1 |

13 | 72 | 1; 3; 5; 6; 7; 8; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 19; 20 | |

| 2.2. General communication about precautions to family | “Creating/increasing listserv communication to update families, such as advising to not visit.”5 | 3 | 4 | 5; 8; 12 | |

| 2.3. Alternative ways of in-person visits with family and physicians | “Primary care providers are encouraged to work with care home staff to enable video consultations”15 “Schedule phone or video conferencing between the residents and families”8 |

9 | 14 | 1; 5; 6; 8; 9; 10; 13; 1415 | |

| Theme 3: Education and information about prevention, control, and early COVID-19 symptom recognition and treatment | 10 | 25 | |||

| 3.1. Education and information for residents and family | “Provide information sessions for residents on COVID-19 to inform them about the virus, the disease it causes, and how to protect themselves from infection”1 | 5 | 5 | 1; 3; 5; 6; 12 | |

| 3.2. Education for staff | “We recommend facilities re-educate all staff, clinical and nonclinical on proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and infection control practices.”7 | 8 | 20 | 1; 5; 7; 8; 12; 13; 14; 15 | |

| Theme 4: Surveillance/monitoring and identification of suspected COVID-19 | 13 | 40 | |||

| 4.1. Early COVID symptom recognition and general screening advice | “The facility should ensure that there is active monitoring of residents, twice daily, for signs and symptoms of respiratory illness or changes in their baseline condition, for example, increased confusion, falls, and loss of appetite or sudden deterioration in chronic respiratory disease.”12 | 12 | 25 | 1; 3; 5; 6; 7; 8; 12; 13; 14; 15; 19; 20 | |

| 4.2. Typical symptoms and multimorbidity in older adults | “Elderly persons often have nonclassic respiratory symptoms”12 | 7 | 15 | 3; 8; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15 | |

| Theme 5: Testing for CoV-SARS-19 | “Any suspect case in these facilities should be under investigation and tested.”20 | 1 | 2 | 20 | |

| Theme 6: Hospital admission and transfer procedures | 12 | 40 | |||

| 6.1. Transfer of healthy adults to home/other setting | “Any request to transfer a resident from the ARC bubble to the family household bubble during the period of lockdown should be determined on an exceptional basis.”20 | 1 | 1 | 20 | |

| 6.2. New admissions into the LTCF | “Care homes should remain open to new admissions as much as possible”15 “Where there is evidence of a cluster or outbreak of COVID-19 … the facility should close to admissions day care facilities and visitors.”14 |

7 | 11 | 7; 8; 12; 13; 14; 15; 20 | |

| 6.3. Procedures for hospital transfers (how and what staff should do and communicate to emergency staff and geriatric departments) | “Before transfer, emergency medical services and the receiving facility should be alerted to the resident's diagnosis, and precautions to be taken including placing a facemask on the resident during transfer.”5 | 5 | 8 | 5; 8; 11; 14; 19 | |

| 6.4. Triage advice regarding hospital or ICU transfers | “Decisions to deny or prioritize care should always be discussed with at least two, but preferably three physicians with experience in the treatment of respiratory failure in the ICU.”21 “GP and ambulance services may aim to triage residents remotely, based on the level of carer concern and their vital signs.”15 |

2 | 5 | 15; 21 | |

| 6.5. (re)admissions to nursing home (from hospital) | “Residential facilities must support the return of their residents from hospital once they are medically stable”20 “Nursing homes should admit any individuals that they would normally admit to their facility, including individuals from hospitals where a case of COVID-19 was/is present.”5 |

8 | 15 | 1; 5; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 20 | |

| Theme 7: General treatment advice for early COVID-19 symptoms | “Approach for fever—nonpharmacological approach: Icepacks at the groin region of body—A wet washcloth—Refresh the patient regularly—Change sheets and clothes—Install a fan”21 | 5 | 22 | 3; 10; 17; 19; 21 | |

| Theme 8: General psychosocial support regarding loneliness, stress, and anxiety not related to end of life | 8 | 23 | |||

| 8.1. for residents | “Care home staff are encouraged to work with residents to address their fears”15 | 7 | 11 | 1; 8; 10; 12; 14; 15; 18 | |

| 8.2. for family | “Ensure family members have access to psychosocial support.”18 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 8.3. for staff | “Regularly and supportively monitor all staff for their well-being and foster an environment for timely communication and provision of care with accurate updates.”1 | 5 | 10 | 1; 12; 15; 18; 21 | |

| Theme 9: Specific considerations for people living with dementia | “Care homes should have standard operating procedures for isolating residents who ‘walk with purpose’ (often referred to as ‘wandering’) as a consequence of cognitive impairment. Behavioral interventions may be employed but physical restraint should not be used.”15 “It may be more difficult for temporary staff members [to know the person living with dementia] … A nurse, or social worker or staff … should complete a personal information form.”9 |

6 | 11 | 6; 9; 13; 14; 15; 20 | |

| palliative Care Themes | |||||

| Theme 1: Saying goodbye, visits at the end of life and bereavement | 17 | 34 | |||

| 1.1. Family preparation for impeding death or severe symptoms of resident | “The procedure for patients with severe pneumonia should be discussed with their relatives”19 “Communicating openly with everyone involved about the impending death”21 |

4 | 4 | 9; 10; 19; 21 | |

| 1.2. Visits in end-of-life/compassionate situations | “Family & friends should be advised that all but essential visiting (for example end of life) is suspended in the interest of protecting residents at this time.”12 “Facilities should restrict visitation of all visitors and nonessential health care personnel, except for certain compassionate care situations, such as an end-of-life situation.”4 |

12 | 28 | 1; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 11; 12; 14; 15; 17; 20 | |

| 1.3. Family bereavement | “Geef reeds aan hoe de postmortale zorg geregeld is” [Indicate how bereavement care is arranged]10 | 2 | 2 | 10; 18 | |

| Theme 2: Symptom management at end of life | 8 | 38 | |||

| 2.1. Comfort care in general without reference to specific symptoms | “Medications meant to provide comfort, including at the end of life … morphine, lorazepam, and similar agents.”8 | 1 | 4 | 8 | |

| 2.2. Delirium | “Delier - haloperidol <70 jaar: x mg … ” [medication for delirium]10 | 2 | 2 | 10; 11 | |

| 2.3. Dyspnea | “DYSPNOE in the terminal phase: in patient who does not use opioids—start morphine continuously … ”21 | 2 | 3 | 10; 21 | |

| 2.4. Anxiety, agitation, or terminal restlessness | “For agitation/restlessness: METHOTRIMEPRAZINE …”16 | 3 | 7 | 10; 16; 21 | |

| 2.5. Breathlessness or respiratory secretion | “Respiratory secretions/congestion near end-of-life. Advise family & bedside staff: not usually uncomfortable, just noisy, due to patient weakness/not able to clear secretions”16 “Oxygen should not be boosted based on oxygen saturation; it is part of normal dying that a patient desaturates”21 |

4 | 6 | 3; 10; 16; 21 | |

| 2.6. Adapting or discontinuation of (burdensome) medication | “No longer measure saturations in a terminal phase”21 “Early detection of inappropriate medication prescriptions is recommended to prevent adverse drug events and drug interactions”3 |

5 | 9 | 3; 10; 14; 19; 21 | |

| 2.7. Palliative (deep) sedation | “If the measures described above with morphine and low-dose benzodiazepines (midazolam) provide insufficient symptom control and the shortness of breath or choking sensation is refractory, initiate DEEP SEDATION if possible after consultation with family and caregivers.”21 | 3 | 7 | 10; 11; 21 | |

| Theme 3: Spiritual care, including religious or cultural support at the end of life | “Specialists in pastoral care as a discipline for spiritual care are present and part of the expanded care team available and make residents, relatives, as well as employees offer spiritual support” [translation by authors]18 “Religious/cultural support and rites may be very important to some residents of RCF, in particular toward end of life”12 |

3 | 10 | 12; 14; 18 | |

| Theme 4: Clinical decision-making toward the end of life | 13 | 41 | |||

| 4.1. Frailty/capacity screening to guide clinical decision-making | “Health care professionals may find the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) to be a useful resource in making and discussing escalation decisions”15 “Nursing home population mainly has CFS below 6-9, at which stage hospital admission for COVID-19 might not be adding much value” (translation by authors)11 |

4 | 8 | 11; 13; 15; 21 | |

| 4.2. Specialist advice and multidisciplinary collaboration in clinical decision-making | “The GP and/or ARC facility (when GP is unavailable) will access specialist advice by telephone (geriatrician/general medicine) before any transfer to hospital.”20 “Ensure multidisciplinary collaboration among physicians, nurses, pharmacists, other health care professionals in the decision-making process to address multimorbidity and functional decline”3 |

4 | 5 | 3; 13; 15; 20 | |

| 4.3. Appropriateness of CPR, oxygen administration, or mechanical ventilation | “Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) should never be considered in this age group regardless of COVID-19.”21 “Very few mechanically ventilated elderly patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) survive.”17 |

3 | 6 | 6; 9; 12 | |

| 4.4. Appropriateness of hospital/ICU admission | “For residents with mild illness, we recommend to treat-in-place. For those with moderate to severe symptoms, consider hospital transfer if that is part of their goals of care.”8 “The question whether hospital admission is indicated for elderly COVID-19 patients with multimorbidity needs to be very carefully considered; it may only be appropriate in the event of complications of concurrent diseases”17 |

11 | 22 | 3; 8; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 17; 19; 20; 21 | |

| Theme 5: Foreseeing stock of medication and prescription chart to enable palliative care | “Care homes should work with GPs and local pharmacists to ensure that they have a stock of anticipatory medications and the community prescription chart, to enable, at short notice, palliative care for residents”15 | 1 | 2 | 15 | |

| Theme 6: Need for specialist palliative care advice and involvement of palliative care teams | “If a difficult course is to be expected, a specialized palliative care team can also be called in for palliative care … ”19 “If required, MPC [mobile palliative care] teams are also to be called in to residential and nursing homes to ensure optimal treatment”17 |

7 | 10 | 8; 10; 15; 16; 17; 19; 21 | |

| Theme 7: Communication about wishes regarding care and treatment, advance care planning, and goals of care discussions in emergency situations | “BEFORE enacting these recommendations, PLEASE clarify patient's GOALS OF CARE these recommendations are consistent with: DNR, no ICU transfer, comfort-focused supportive care”16 “Assess the appropriateness of hospitalization: consult the resident's Advance Care Plan/Treatment Escalation Plan and discuss with the resident and/or their family”13 |

14 | 33 | 3; 5; 8; 9; 10; 11; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17; 19; 20; 21 | |

| Theme 8: Preparations of the body and funeral arrangements | “To date, there is no evidence of persons having become infected from exposure to the bodies of persons who died from COVID-19.”2 “It is crucial to abide by guidance on the preparation of the body and transportation.”14 |

4 | 10 | 2; 12; 13; 14 | |

Bold is overall sum of number of documents in which the theme was addressed.

Twelve documents state that exceptions to restrictions can be made for family visits to residents who are at the end of life, called “compassionate situations” in the U.S. However, all 12 documents state these visits are restricted to a certain maximum number of visits a day, one visitor at the time, and that respiratory, hand hygiene, and distancing measures must be observed. Two documents recommend two weeks of self-isolation of visitors. Some documents are more strict than others regarding who might visit in these circumstances, that is, no children, persons who are not chronically ill, and without COVID-19 symptoms.

Fourteen documents that mention ACP primarily refer to transfers to hospital and/or focused primarily on written plans or orders (such as Provider Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment or POLST) to guide emergency situations. In particular, eight documents state that consulting a person's advance care plan is crucial to take into account when deciding whether they should be hospitalized. A matter of urgency is acknowledged in all documents, stating that residents' advance directives/advance care plans should be completed and up to date; in U.S. documents, it is added that written physician orders must reflect patients' wishes. Seven documents are more specific to what the advance care plan should at least entail: who is the Lasting Power of Attorney (n = 1), whether or not it is desirable to initiate CPR (n = 5), admission to the hospital or ICU (n = 5), endotracheal intubation (n = 2), noninvasive mechanical ventilation (n = 3), fluids (n = 1), antibiotics (n = 1), pharmacological hemodynamic support (n = 1), renal replacement therapy (n = 1), or comfort care (n = 4). Four documents acknowledge that plans may need to be made in emergency situations, with little time available. Six documents highlight the importance of involving representatives/family in goal-setting or ACP. Three documents explicitly state that ACP is a person-centered approach to care, that involves “effective” or “adequate, sympathetic” communication and a thorough understanding of a person's life, values, priorities, and preferences.

Ten documents generally advise against hospital/ICU admissions of COVID-19 patients from nursing homes, unless “clinically indicated.” Documents differ in the strength with which they advise against admissions. While some, especially in Belgium and Scotland, say that this is not advised, U.S. documents make less prescriptive statements. Four documents suggest using the Clinical Frailty Scale to decide whether to hospitalize, but different Clinical Frailty Scale cutoff scores are suggested in the different countries.

Discussion

In the 21 COVID-19 guidance documents concerning palliative or end-of-life care in nursing homes we identified worldwide, a wide range of palliative care topics were addressed, albeit to limited extent. Most recommendations concern very specific clinical tasks or subjects such as visits or hospital admissions, while several key aspects of palliative care, practical guidance, and broader structural and coordination considerations are largely absent.27 International WHO guidance focused on infection prevention and control, body and funeral arrangements, and respiratory symptom management only, while including limited recommendations on palliative care–related topics. Essential aspects of palliative care6 , 28 that were not fully addressed include the following: holistic symptom assessment and management at the end of life (including stockpiling medications and equipment), staff training (in particular for care assistants who deliver the majority of hands-on care in these settings) regarding communication, decision-making and comfort for dying residents, referral to specialist palliative care or hospice, comprehensive ACP communication (not limited to documentation), support for family including bereavement care, support for staff, and leadership and coordination related to palliative care.6 , 8 , 27 , 28 Documents also did not provide guidance on deployment of staff such as moving (palliative care) staff from acute settings to the community.6 , 28

Several specific observations should be highlighted. First, although most documents addressed early physical symptom management in COVID-19, only a few made specific recommendations regarding symptoms at the end of life. Nonphysical (psychological, social, or spiritual) needs were hardly addressed. Moreover, attention to dementia was limited to “wandering” residents. This is an important omission given that the majority of nursing home residents have dementia, and the current crisis poses many challenges to them.29 , 30 Several Alzheimer's associations have started drafting COVID-19 guidance specifically for this population,31 , 32 and future nursing home guidance should integrate this. Second, many documents highlight that the restriction of visits can be lifted for dying residents (although strict criteria apply) but fail to provide guidance on supporting family, especially regarding bereavement—although measures, such as physical distancing, might negatively impact the grieving process.33 Third, although it is remarkable that ACP is mentioned in many documents, it is discussed in a very limited way. The emphasis lies on treatment preferences in writing (i.e., do-not-hospitalize or DNR), while the actual communication process is less frequently mentioned.34

This is the first published study that reviewed international COVID-19 guidance for a highly vulnerable population. Its strengths include its international focus—although all included documents are from high-income countries, despite our search including low- and middle-income countries—and use of rigorous and established methods for documentary and qualitative analysis. We may have missed eligible documents, given reliance on country representatives to make a first selection. Also, we did not analyze countries' different regulatory, health care, and cultural contexts.

Given rapid development of the pandemic and deficits in palliative and end-of-life care in nursing homes even before this pandemic,35 the dearth of guidance is perhaps not surprising. However, important efforts are needed to fulfill the call for high-quality palliative care for people with COVID-19,5 specifically for the highly vulnerable population of nursing home residents.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The PACE (Palliative Care for Older People in Care and Nursing Homes in Europe) consortium, Meera Agar (Australia), Rufus Akinyemi (Nigeria), Alejandra Guerrero Barragán (Columbia), Michal Boyd (New Zealand), Anna Brugulat-Serrat (Spain), Rob Bruntink (The Netherlands), Natalia Arias Casais (WHO), Carlos Centeno (Spain), Melissa Chan (Singapore), Yaohua Chen (France), Myriam De la Cruz Puebla (Ecuador), Lissette Duque (Ecuador), Neus Falgas (Spain), Merryn Gott (New Zealand), Zeea Han (WHO), Katharina Heimerl (Austria), Susan Hickman (USA), Sandra Higuet (Belgium), Jo Hockley (UK), Hany Ibrahim (Egypt), Nicholas Jennings (Trinidad and Tobago), Marcos Lama (India), Shamiel McFarlane (Jamaica), Diane Meier (USA), Fanny Monnet (Switzerland/Belgium), Sean Morisson (USA), Miharu Nakanishi (Japan), Bregje Onwuteaka-Philipsen (The Netherlands), Roeline Pasman (The Netherlands), Sophie Pautex (Switzerland), Sheila Payne (UK), Reidar Pedersen (Norway), Fernando Peres (Brazil), Mirko Petrovic (European Geriatric Medicine Society (EUGMS), Ruth Piers (Belgium), YongJoo Rhee (South Korea), Jacqualine Robinson (New Zealand), Trygve Johannes Saevereid (Norway), Katarzyna Szczerbinska (Poland), Nhu Tram (Age Platform Europe), Nele Van den Noortgate (Belgium), Jenny Van der Steen (The Netherlands), and Hein PJ van Hout (The Netherlands).

The authors have no conflicts of interest. Kathleen Unroe is the founder and CEO of Probari, a health care start-up designed to disseminate the OPTIMISTIC clinical care model to reduce nursing home to hospital transfers.

Joni Gilissen is supported by the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI), Atlantic Philanthropies (USA). Lara Pivodic is a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Research Foundation-Flanders, Belgium. The sponsors had no role in design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

Footnotes

G. J. and P. L. contributed equally as first authors.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Characteristics of Guidance Documents, per Country, Type, and Number of Palliative Care Themes Addressed

| No | Issuing Body | Title | Date Issued (Last Update Included in This Study) | Country in Which Issued | Target Audience (as Mentioned in Document) | Purpose of Guidance (as Mentioned in Document) | Typea | Number of Palliative Care Themes Addressed in Document | Methods and Sources Used to Develop Guideline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WHO (World Health Organization) | Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) guidance for long-term care facilities in the context of COVID-19′ | 21/03/20 | International | This interim guidance is for LTCF managers and corresponding IPC (infection prevention and control) focal persons in LTCF. | To provide guidance on IPC in LTCFs in the context of COVID-19 to 1) prevent virus from entering the facility, 2) prevent COVID-19 from spreading within the facility, and 3) prevent from spreading to outside the facility. | Type 4 | 1 (end-of-life visitations) | NA |

| 2 | WHO (World Health Organization) | Infection Prevention and Control for the safe management of a dead body in the context of COVID-19 | 24/03/20 | International | For all those, who tend to the bodies of persons who have died of suspected or confirmed COVID-19, including managers of health care facilities and mortuaries, religious and public health authorities, and families | Guidance on how to tend the bodies of persons who have died of suspected or confirmed COVID-19. | Type 5 | 1 (preparation of body and funeral arrangements) | NA |

| 3 | WHO (World Health Organization) | Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected | 13/03/20 | International | Clinicians involved in the care of adult, pregnant, and pediatric patients with or at risk for severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when a SARS-CoV-2 infection is suspected | To strengthen clinical management of patients who are at risk for SARI when SARS-CoV-2 infection is suspected, and to provide up-to-date guidance. | Type 5 | 3 (clinical decision-making, symptom management at end of life, ACP) | Based on evidence-informed guidelines developed by multidisciplinary panel of health care providers with experience in the clinical management of patients with COVID-19 and other viral infections. |

| 4 | Centers from Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) and National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) | Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Nursing Homes with Hospice Patients Guidance for Infection Control and Prevention (additional guidance on compassionate situations) | 13/03/20 (14/03/20 by NHPCO) | US | For hospice workers in nursing homes | Specific guidance for visitation for certain compassionate care situations, such as end of life, and details for hospice workers in nursing homes | Type 1 | 1 (end-of-life visitation) | NA |

| 5 | Centers from Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), Department of Health & Human Services, Center for Clinical Standards and Quality, Safety and Oversight Group | Guidance for Infection Control and Prevention of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Nursing Homes (REVISED), including updated version of 03/04/2020 | 13/03/20 (03/04/20) | US | State Survey Agency Directors (nursing homes) | Guidance to nursing homes to help them improve their infection control and prevention practices to prevent the transmission of COVID-19, including revised guidance for visitation. | Type 4 | 2 (ACP and end-of-life visitation) | NA |

| 6 | The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine–American Medical Directors Association (AMDA), and American Assisted Living Nurses Association (AALNA) | Guidance & Resources for Assisted Living Facilities and Continuing Care Retirement Communities During COVID-19 | 01/04/20 | US | For Assisted Living (AL) Communities, Personal Care Homes, Senior Living Communities, and Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRC), henceforth referred to as ALs and CCRCs | To address the challenges that are distinctive to these communities and offer resources | Type 4 | 1 (end-of-life visitation) | NA |

| 7 | The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine–American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) | COVID-19 guidance for PALTC (Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine) | 27/03/20 | US | Health care personnel working in postacute and long-term care (PALTC) settings | Not stated | Type 4 | 1 (end-of-life visitation) | NA |

| 8 | The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine–American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) | Frequently Asked Questions Regarding COVID-19 and PALTC | 31/03/20 | US | Health care personnel working in postacute and long-term care (PALTC) settings | This document assumes that there is community spread of COVID-19 in your region and provides answers to frequently asked questions from PALTC (Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine) | Type 4 | 4 (specialist PC, symptom management, ACP, end-of-life visitation) | NA |

| 9 | Alzheimer's Association | Emergency Preparedness: Caring for persons living with dementia in a long-term or community-based care setting | No date | US | Employees of long-term and community-based care settings | To provide suggestions to meet the needs of persons living with dementia during a major disease outbreak or disaster | Type 4b | 2 (preparing family, ACP) | NA |

| 10 | Verenso (beroepsvereniging van verpleeghuisartsen en specialisten ouderengeneeskunde) [Verenso (professional organization for nursing home physicians and specialists geriatric medicine)] and Palliaweb | Symptoombestrijding in de verpleeghuissituatie bij patiënten met een COVID-19 (Corona) in de laatste levensfase' [Symptom management in nursing homes for patients that have COVID-19 in end of life/terminal phase] | 24/03/20 | The Netherlands | Specialisten Ouderengeneeskunde, verpleegkundigen en verzorgenden in het verpleeghuis [Specialists geriatric medicine, nurses, and care assistants in nursing homes] | Handvatten aanreiken bij symptoombestrijding tijdens de Coronacrisis [To provide recommendations regarding symptom management during corona crisis] | Type 1 | 5 (end-of-life visitation, symptom management, clinical decision-making, ACP, specialist PC) | NA |

| 11 | Federatie Medisch Specialisten (FMS) Nederland and verpleeghuisartsen [Federation Medical Specialists and nursing home physicians] | Leidraad triage thuisbehandeling versus verwijzen naar het ziekenhuis bij oudere patiënt met (verdenking op) COVID-19 [Guideline triage care treatment and home and admission to hospital of older patient in case of suspecting COVID-19] | 27/03/20 | The Netherlands | Not stated | De Leidraad biedt concrete aandachtspunten en besluitvormingscriteria voor de verwijzing en behandeling van oudere patiënten met een (verdenking op) COVID-19 virusinfectie [The guideline is intended to provide guidance and decision-making criteria for transferring and treating older patients who are suspected to be infected by COVID-19] | Type 2 | 4 (clinical decision making, ACP, end-of-life visitation, symptom management) | We used local protocols and flowcharts. The first version of this document is mainly based on expert-opinion and experience-based. |

| 12 | Ireland Health Services (HSE) and the Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC) | Preliminary Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Infection Prevention and Control Guidance including Outbreak Control in Residential Care Facilities (RCF) and Similar Units [new title after update: Interim Infection Prevention and Control Guidance including Outbreak Control in Residential Care Facilities (RCF) and Similar Units for pandemic COVID-19] | 30/03/20 (updated: 08/04/20) | Ireland | Community residential facilities | This document provides guidance and information on infection prevention and control measures to inform and advise local planning and management in community residential facilities. | Type 4 | 4 (preparation of body and funeral arrangements, clinical decision making, spiritual care, end-of-life visitation) | Inspired by several guidance documents from Communicable Disease Network Australia, Health Protection Scotland, WHO, and HIQA rapid review of public health guidance on infection prevention and control measures for residential care facilities |

| 13 | Department of Health & Social Care, Public Health England, Care Quality Commission, and NHS | Admission and Care of Residents during COVID-19 Incident in a Care Home | 02/04/20 | UK | Care home providers and staff | We want to support care home providers to protect their staff and residents, ensuring that each person is getting the right care in the most appropriate setting for their needs. | Type 4 | 5 (clinical decision making, specialist PC, preparation of body and funeral arrangements, ACP) | NA |

| 14 | Scottish Government/Riaghaltas na h-Alba (gov.scot) | Coronavirus (COVID-19): clinical guidance for nursing home and residential care residents | 13/03/20 (updated: 16/03/20) | UK | Those working with adults in long-term care such as residents of nursing home and residential care settings | This guidance provides targeted clinical advice about COVID-19. | Type 4 | 6 (spiritual care, symptom management, preparations of body and funeral, clinical decision making, ACP, end-of-life visitation, incl bereavement) | NA |

| 15 | British Geriatrics Society (BGS) | COVID-19: Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in care homes | 25/03/20 | UK | First, care home staff, many of whom feel isolated and exposed as part of the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, NHS staff who plan for, work with, and support care home staff, many of whom are trying to develop standardized approaches to care home residents in light of the pandemic. | To help care home staff and NHS staff who work with them to support residents through the pandemic. | Type 2 | 5 (specialist PC, clinical decision making, end-of-life visitation, foreseeing stock, ACP) | Expert author group who assembled this guidance with BGS |

| 16 | BC Centre for Palliative Care Guidelines | Symptom management for adult patients with COVID-19 receiving end-of-life supportive care outside of the ICU | 20/03/20 | Canada | Not stated | Symptom management for adult patients with COVID-19 who receive end-of-life supportive care outside ICU | Type 3 | 3 (ACP, symptom management, specialist PC) | Recommendations compiled collaboratively with input from a team of BC palliative care MDs, pharmacists & allied health. |

| 17 | Roland K. & Markus, M. (Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Stadtspital Waid und Triemli & Spital Affoltern am Albis), approved by Association for Geriatric Palliative Medicine (FGPG) | COVID-19 pandemic: palliative care for elderly and frail patients at home and in residential and nursing homes | 22/03/20 | Switzerland | Not stated | To provide recommendations for practice (palliative care for older adults in nursing homes) | Type 1 | 4 (end-of-life visitation, clinical decision-making, specialist PC, ACP) | NA |

| 18 | Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Palliative Medizin, Pflege und Begleitung [Swiss Society for Palliative Medicine, Nursing and Support] | COVID-19 - Pandemie – Merkblatt zu Spiritual Care und Seelsorge in Langzeitpflegeinstitutionen' [Spiritual care and chaplaincy in LCTFs for COVID 19 patients] | 27/03/20 | Switzerland | Intended as a recommendation for: specialists in pastoral care in retirement and nursing homes, health professionals and those responsible in medical institutions, responsible for the appointing authorities for pastoral workers | Guidance regarding spiritual care and pastoral care in long-term care | Type 2 | 2 (spiritual care, end-of-life visitation) | These recommendations are based on a handout from the Reformed Church of Bern-Jura-Solothurn. |

| 19 | Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Palliative Medizin, Pflege und Begleitung [Swiss Association for Palliative Medicine, Care and Support] | Merkblatt für HausärztInnen Palliative Behandlung von COVID19 zu Hause und im Pflegeheim [Leaflet for general practitioners and palliative treatment of COVID19 at home and in a nursing home] | 24/03/20 (updated: 06/04/20) | Switzerland | General practitioners, Spitex (extramural care, home care) and nursing homes | To ensure good palliative care at home or in nursing homes for elderly and seriously ill patients who no longer want (or no longer receive) intensive care treatment | Type 1 | 5 (clinical decision making, specialist PC, ACP, preparing family, symptom management) | NA |

| 20 | New Zealand Government, Ministry of Health | 1) ‘Update for Disability and Aged Care Providers on Alert Level 4' (30/03/20)' 2) ‘COVID-19 Guidance for admissions into aged residential care facilities at Alert Level 4' (02/04/20) 3) ‘Updated advice for health professionals: novel coronavirus' (COVID-19) (08/04/20) |

30/03/20 (updated: 02/04/20; updated: 08/04/20) | New Zealand | Health professionals in general (including hospital-based, community-based, and public health practitioners) and disability and aged residential care facilities specifically |

1) To provide update on COVID Alert Level 4 2) To provide guidance for admissions into aged residential care 3) To provide information on how to identify and investigate any cases of novel coronavirus (COVID-19), as well as how to apply appropriate contact tracing and infection control measures to prevent its spread |

Type 4 | 3 (clinical decision-making, ACP, end of life visitation) | Information in this document is based on current advice from the WHO. |

| 21 | Group of Belgian geriatricians (University Hospital Leuven, University Hospital Gent and Crataegus) | COVID-19 Guideline regarding Symptom Management and Clinical Decision-Making in Nursing Homes | 25/03/20 | Belgium | Long-term care facilities | To support nursing home staff in symptom management and clinical decision-making regarding hospital admission at the end of life | Type 2 | 4 (clinical decision-making, end of life visitation, symptom management, ACP) | Developed by group of multiple physicians. |

WHO = World Health Organization; NA = not available; BGS = British Geriatrics Group; ACP = advance care planning; PC = palliative care.

Type of guidance document: 1) Palliative care document with substantial section of specific recommendations for nursing homes; 2) Nursing home document with substantial section including specific recommendations regarding palliative care; 3) Palliative care documents specifically for nursing homes; 4) Nursing home document with limited advice for palliative care; 5) Document that relates to specific end-of-life theme which is highly relevant for nursing home population. Note that the fact that some documents cover multiple palliative care themes does not imply that all themes are addressed in equal depth.

Guidance document is aimed at health care providers working for people living with dementia, not specifically for nursing homes. Given that nursing home population has high prevalence of dementia, we considered this to be a guidance document specifically for nursing homes.

References

- 1.Shahid Z., Kalayanamitra R., McClafferty B., Kepko D., Ramgobin D. COVID-19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jgs.16472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Half of coronavirus deaths happen in care homes, data from EU suggests. The Guardian. 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/13/half-of-coronavirus-deaths-happen-in-care-homes-data-from-eu-suggests Available from.

- 3.Comas-Herrera A., Zalakain J. Mortality associated with COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: early international evidence. International Long-Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE; 2020. https://ltccovid.org/2020/04/12/mortality-associated-with-covid-19-outbreaks-in-care-homes-early-international-evidence/ Available from.

- 4.Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Editorial Palliative care and the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30822-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etkind S.N., Bone A.E., Lovell N. The role and response of palliative care and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: a rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radbruch L., Knaul F.M., de Lima L., de Joncheere C., Bhadelia A. The key role of palliative care in response to the COVID-19 tsunami of suffering. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30964-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macleod R.D., Van den Block L. Springer Nature; Switzerland: 2019. Textbook of Palliative Care. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Nursing Homes with Hospice Patients Guidance for Infection Control and Prevention (Additional guidance on compassionate situations) Centers from Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) and National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO); USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidance for Infection Control and Prevention of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Nursing Homes (REVISED), including updated version of 03/04/2020. Centers from Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), department of Health & human Services, Center for Clinical Standards and Quality, Safety and Oversight Group; USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Symptom management for adult patients with COVID-19 receiving end-of-life supportive care outside of the ICU. BC Centre for Palliative Care Guidelines; Canada: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.COVID-19 guidance for PALTC (Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine) The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine - American Medical Directors Association (AMDA), and American Assisted Living Nurses Association (AALNA); USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frequently Asked Questions Regarding COVID-19 and PALTC. The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine - American Medical Directors Association (AMDA); USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guidance & Resources for Assisted Living Facilities and Continuing Care Retirement Communities During COVID-19. The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine - American Medical Directors Association (AMDA), and American Assisted Living Nurses Association (AALNA); USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emergency Preparedness: Caring for persons living with dementia in a long-term or community-based care setting. USA: Alzheimer's Association; no date.

- 16.Symptoombestrijding in de verpleeghuissituatie bij patiënten met een COVID-19 (Corona) in de laatste levensfase. Verenso (beroepsvereniging van verpleeghuisartsen en specialisten ouderengeneeskunde) [Verenso (professional organisation for nursing home phyisicans and specialists geriatric medicine)] and Palliaweb; The Netherlands: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leidraad triage thuisbehandeling versus verwijzen naar het ziekenhuis bij oudere patiënt met (verdenking op) COVID-19. Federatie Medisch Specialisten (FMS) Nederland and verpleeghuisartsen [Federation Medical Specialists and nursing home physicians]; The Netherlands: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preliminary coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infection prevention and control guidance including outbreak control in Residential Care Facilities (RCF) and similar units [new title after update: interim infection prevention and control guidance including outbreak control in Residential Care Facilities (RCF) and similar units for pandemic COVID-19] Ireland Health Services (HSE) and the Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC); Ireland: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coronavirus (COVID-19): clinical guidance for nursing home and residential care residents'. Scottish Government/Riaghaltas na h-Alba (gov.scot); Scotland: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.COVID-19: Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in care homes. British Geriatrics Society (BGS); UK: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Admission and Care of Residents during COVID-19 Incident in a Care Home. Department of Health & Social care, Public Health England, Care Quality Commission and NHS; UK: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roland K., Markus M. Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Stadtspital Waid und Triemli & Spital Affoltern am Albis, approved by Association for Geriatric Palliative Medicine (FGPG); Switzerland: 2020. COVID-19 pandemic: palliative care for elderly and frail patients at home and in residential and nursing homes. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merkblatt für HausärztInnen Palliative Behandlung von COVID19 zu Hause und im Pflegeheim. Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Palliative Medizin, Pflege und Begleitung [Swiss Association for Palliative Medicine, Care and Support]; Switzerland: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.COVID-19 - Pandemie – Merkblatt zu Spiritual Care und Seelsorge in Langzeitpflegeinstitutionen. Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Palliat Medizin, Pflege Begleitung [Swiss Soc Palliat Med Nurs Support]; Switzerland: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Update for Disability and Aged Care Providers on Alert Level 4 (30/03/20); COVID-19 Guidance for admissions into aged residential care facilities at Alert Level 4 (02/04/20); Updated advice for health professionals: novel coronavirus (COVID-19) (08/04/20) New Zealand Government, Ministry of Health; New Zealand: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.COVID-19 Guideline regarding Symptom Management and Clinical Decision-Making in Nursing Homes. Group of Belgian geriatricians (University Hospital Leuven, University Hospital Gent and Crataegus); Belgium: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrell B.R., Twaddle M.L., Melnick A., Meier D.E. National consensus project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care guidelines, 4th edition. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:1684–1689. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downar J., Seccareccia D. Palliating a pandemic: “all patients must be cared for. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H., Li T., Barbarino P. Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1190–1191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30755-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honinx E., van Dop N., Smets T. Dying in long-term care facilities in Europe: the PACE epidemiological study of deceased residents in six countries. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1199. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7532-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Living with dementia - COVID-19 Alzheimer Europe. 2020. https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Living-with-dementia/COVID-19 Available from.

- 32.Alzheimer's association COVID-19 professional care guidelines. Alzheimer's Dis Demen. https://alz.org/professionals/professional-providers/coronavirus-covid-19-tips-for-dementia-caregivers

- 33.Wallace C.L., Wladkowski S.P., Gibson A., White P. Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rietjens J.A.C., Sudore R.L., Connolly M. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e543–e551. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30582-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pivodic L., Smets T., Van den Noortgate N. Quality of dying and quality of end-of-life care of nursing home residents in six countries: an epidemiological study. Palliat Med. 2018;32:1584–1595. doi: 10.1177/0269216318800610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]