Abstract

The two studies presented in this article examine the relationships of personality traits and trait emotional intelligence (EI) with compassion and self-compassion in samples of Italian workers. Study 1 explored the relationship between trait EI and both compassion and self-compassion, controlling for the effects of personality traits in 219 workers of private Italian organizations. Hierarchical regression analyses revealed that trait EI explained variance beyond that accounted for by personality traits in relation to both compassion and self-compassion. Study 2 analyzed the contribution of trait EI in mediating the relationship between personality traits and both compassion and self-compassion of 231 workers from public Italian organizations with results supporting the mediating role of trait EI.

Keywords: Compassion, Self-compassion, Trait emotional intelligence, Personality traits

1. Introduction

The complexities of the 21st century characterized by instability, insecurity and continuous changes (Blustein, Kenny, Di Fabio, & Guichard, 2019; Peiró, Sora, & Caballer, 2012) pose challenges to the well-being of individuals in all aspects of daily life (Di Fabio and Kenny, 2016a, Di Fabio and Kenny, 2016b, Di Fabio and Kenny, 2018). This has led to the growth of positive psychology and the development and promotion of strength-based intervention and prevention initiatives (Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014a, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014b, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2018, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2019) that are amenable to specific training to support the health and well-being of individuals. Research has clearly supported that a strength-based focus (Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014a, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014b, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2018, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2019) is also critical in promoting the positive capacity of the various organizations, including the work place, to support the people who comprise them (Blustein, 2011; Peiró, 2008; Peiró, Bayonab, Caballer, & Di Fabio, 2020; Tetrick & Peiró, 2012). The insecurity of the current working context due to, for example, automation, changing consumer demands, and most recently the Covid-19 pandemic underscores the importance of creating and promoting healthy work place organizations (Di Fabio, 2017a; Di Fabio & Rosen, 2018). Strength-based perspectives (Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014a, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014b, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2018, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2019) in organizations are centered on fostering workers' resources through early intervention actions that encourage psychological capacity through focused and systemic programs.

Compassion and self-compassion are among the many identified factors linked with psychological health and well-being (Bluth & Neff, 2018; Cassell, 2002; Mwanje, 2018; Reizer, 2019; Worline & Dutton, 2017). Compassion (Gu, Cavanagh, Baer, & Strauss, 2017) and self-compassion (Neff, 2003) are crucial promising resources for promoting healthy organizations, in terms of individual well-being (Bluth & Neff, 2018; López, Sanderman, Ranchor, & Schroevers, 2018; Seppala, Rossomando, & Doty, 2013; Zessin, Dickhäuser, & Garbade, 2015) as well as the promotion of prosocial behaviors towards each other (Condon, 2017; Lindsay & Creswell, 2014; Marshall, Ciarrochi, Parker, & Sahdra, 2019; Runyan et al., 2019; Yang, Guo, Kou, & Liu, 2019).

The construct of compassion (Gu et al., 2017) is defined as the emotional perception and recognition of the suffering of others and the desire to alleviate it, understanding the universality of suffering, feeling moved by the person suffering and emotionally connecting with their distress, and tolerating uncomfortable feelings (e.g., fear, distress) so that we remain open to and accepting of the person suffering. Compassion at work appears to fit directly with the growing focus on relational perspectives at work (Blustein, 2006, Blustein, 2011) and the importance of relationships in organizational contexts for the well-being of workers (Allan, Duffy, & Douglass, 2015; Duffy, Blustein, Diemer, & Autin, 2016). Dutton, Workman, and Hardin (2014) suggested that compassion is embedded in personal, relational and organizational contexts and reported that interpersonal compassion has the potential to affect not only sufferers but also focal actors, third parties, and organizations. Research has shown that people who experienced compassion from others in the workplace show increased positive emotions such as gratitude and reduced anxiety (Lilius et al., 2008) as well as improved commitment to the organization (Grant, Dutton, & Rosso, 2008; Lilius et al., 2008). Compassion also appears to facilitate the transmission of dignity and worth from one person to another, permitting people at work to feel valued (Dutton et al., 2014; Frost, 2003). Of interest is that compassionate individuals experience more compassion satisfaction when helping others (Stamm, 2002), more pro-social identity as caring person (Grant et al., 2008), and perceive themselves as more effective leaders (Melwani, Mueller, & Overbeck, 2012). A third party effect suggested that observers of compassion seem to feel ‘proud’ when people in their organization are compassionate and encouraging towards others (Dutton, Lilius, & Kanov, 2007; Haidt, 2002).

Compassion observed in organizations appears to foster collective positive outcomes in terms of higher levels of shared positive emotion such as pride and gratefulness (Dutton et al. 2006), greater collective commitment, and lower turnover rates (Grant et al., 2008; Lilius et al., 2008). Compassion shown by co-workers facilitated improved emotional connections at work and increased employees' performance (Dutton, Frost, Worline, Lilius, & Kanov, 2002; Frost, Dutton, Worline, & Wilson, 2000). A longitudinal study (Eldor, 2018) of public service sector employees who received compassionate feelings (e.g., affection, generosity, caring, tenderness) from their supervisors, showed a greater service-oriented performance of compassionate behavior towards clients supporting Chu's (2017) contention that exhibiting compassion could be a crucial aspect of productivity in organizations.

Regarding the association between compassion and well-being, a brief compassion training with a sample of healthy adults resulted in participants' experiencing higher positive affect compared to a control group (Klimecki, Leiberg, Lamm, & Singer, 2012). People who receive compassion appear to recuperate faster from physically from illness (Brody, 1992) and psychologically from grief (Bento, 1994; Doka, 1989). Compassion satisfaction felt by nurses was positively associated with well-being (Kim et al., 2017; Kim & Yeom, 2018) and inversely associated with burnout (Kim et al., 2017).

Extending compassion to the self, self-compassion refers to a regulation strategy in which feelings of worry or stress are not avoided but instead being open and sensitive to one's own suffering, experiencing feelings of care and kindness to oneself, taking an attitude of understanding and not judging one's own inadequacies and failures, and recognizing that one's own experience is part of the common human experience (Neff, 2003). Self-compassion is also associated with feelings of compassion and concern for others so that being compassionate towards oneself does not mean being focused only on one's own personal needs (Neff, 2003). In particular, self-compassion acknowledges that suffering, failure, and inadequacy are part of the human condition and all people, including themselves, are worthy of compassion (Neff, 2003).

Research on self-compassion has shown increased performance and benefits in overcoming mental barriers, aversive thoughts, fear of failure, and negative emotions (Neff & Knox, 2017). Other studies have reported positive associations of self-compassion to goal mastery (Neff, Hsieh, & Dejitterat, 2005) and achievement goals (Ahmet, 2008), again promoting better performance (Barnard and Curry, 2011). A meta-analysis by Zessin et al. (2015) showed showed that self-compassion was positively associated with both subjective well-being, in terms of both positive and negative affect and life satisfaction, and psychological well-being. On the other hand, self-compassion is also negatively associated with psychopathology (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012), and is instrumental in decreasing anxiety and depression (Neff, 2003). The role of self-compassion and well-being has also been observed in the organizational context (Dev, Fernando III, Lim, & Consedine, 2018). Self-compassion is considered a resilience factor that promotes well-being at work (Dev et al., 2018) while showing inverse associations with emotional exhaustion and burnout at the workplace (Alkema, Linton, & Davies, 2008; Dev et al., 2018).

Compassion and self-compassion have been linked with personality traits grounded in models including the BIG 5 and the HEXACO (Arslan, 2016; Goetz, 2008; Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997; Neff, 2003; Neff, Rude, & Kirkpatrick, 2007; Oral & Arslan, 2017; Thurackal, Corveleyn, & Dezutter, 2016). With personality traits being such key predictors of human behaviour, it is not surprising to find that compassion shows a positive relationship with agreeableness (Goetz, 2008; Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997) while self-compassion appears to be inversely related with neuroticism (Arslan, 2016; Neff, 2003; Neff et al., 2007; Oral & Arslan, 2017; Thurackal et al., 2016).

Strength-based preventive studies (Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014a, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014b, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2018, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2019) have also identified emotional intelligence as a promising primary prevention resource (Di Fabio and Kenny, 2011, Di Fabio and Kenny, 2015, Di Fabio and Kenny, 2016b, Di Fabio and Kenny, 2019) since it is amenable to training, in contrast with personality traits which are somewhat more stable (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The two major descriptions of emotional intelligence (Stough, Saklofske, & Parker, 2009) include ability-based models (Mayer & Salovey, 1997) focused on the cognitive dimensions of emotional intelligence (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000) and trait emotional intelligence models (Bar-On, 1997; Petrides & Furnham, 2001) which describe the subjective experience of emotions and to self-evaluation of one's own emotional and social competences (Bar-On, 1997; Petrides & Furnham, 2001). The trait emotional intelligence model developed by Petrides and Furnham (2001) integrates the dimensions included in an earlier model by Bar-On (1997) and focuses on trait emotional self perceptions and self-efficacy related to personality.

Studies regarding the associations between compassion and emotional intelligence are limited in the literature although there is increasing emphasis on considering EI when recruiting for the helping-caring professions where compassion would be a key quality (Lyon, Trotter, Holt, Powell, & Roe, 2013; Nightingale, Spiby, Sheen, & Slade, 2018, Vesely, Saklofske, & Nordstokke, 2014; Vesely-Maillefer & Saklofske, 2018). Nightingale et al. (2018) reviewed 22 papers that explored the relationship between EI and caring behaviour in health care professionals but only one study specifically centered on relationships between EI and compassion. Dafeeah, Eltohami, and Ghuloum (2015) showed that higher EI results in higher nurse/physician self-reported emotional care/compassion compassionate attitudes towards patients with HIV.

In a related vein, Zeidner, Hadar, Matthews, and Roberts (2013), reported that compassion fatigue defined as the negative consequence of working with patients in combination with a deep, personal, empathetic orientation (Abendroth, 2011) was inversely associated with both trait emotional intelligence and ability-based emotion management in health-care professionals. A more recent study of nurses (Beauvais, Andreychik, & Henkel, 2017) showed that compassion fatigue was inversely associated with ability based emotional intelligence whereas compassion satisfaction showed a positive relationship.

Regarding the self-compassion and EI, Neff (2003) highlighted that self-compassion was related the ability to monitor one's own emotions and the ability to skillfully use this information to guide one's thinking and actions. Heffernan, Quinn Griffin, McNulty, and Fitzpatrick (2010), with officers in the Irish Defence Forces reported positive correlations of the TEIQue-SF (Petrides, 2009) total score with self-compassion. Şenyuva, Kaya, Işik, and Bodur (2014) found that nursing students demonstrated a relationship between self-compassion and self-reported emotional intelligence.

Given the increasing support for the role of compassion, self-compassion and emotional intelligence in psychological health and well-being, the two studies presented here further examine their relationship in Italian workers. Study 1 analyzed the relationships of both compassion and self-compassion with trait EI controlling for the effects of the Big Five personality traits. Study 2 verified whether trait EI mediated the relationships between Big Five personality traits and both compassion and self-compassion.

1.1. Study 1

1.1.1. Aim and research questions

This study examined the relationships of both compassion and self-compassion with trait EI factors, controlling for the effects of personality traits (Big Five model) with a sample of workers in private Italian organizations.

The following research questions were examined: trait EI factors are positively associated with compassion and self-compassion, and EI will add additional variance to that accounted for by the Big Five personality traits in relation to compassion and self-compassion.

1.2. Material and methods

1.2.1. Participants

Two hundred and nineteen workers from private Italian organizations participated in the study (54% men, 46% women). The participants ranged in age from 25 to 64 years (M = 40.83, SD = 9.26). The participation rate was 91%.

1.2.2. Measures

1.2.2.1. Big Five Questionnaire (BFQ)

The Big Five Questionnaire (BFQ; Caprara, Barbaranelli, & Borgogni, 1993) is composed of 132 items answered on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Absolutely false to 5 = Absolutely true). The questionnaire assesses five personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness.

The Cronbach alpha coefficients in the present study were 0.80 for extraversion, 0.79 for agreeableness, 0.82 for conscientiousness, 0.89 for emotional stability, and 0.79 for openness.

1.2.2.2. Trait EI Questionnaire Short Form (TEIQue-SF)

The Trait EI Questionnaire Short Form (TEIQue-SF, Petrides, 2009), translated into Italian by Di Fabio and Palazzeschi (2011) includes 30 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale format (1 = Completely disagree to 7 = Completely agree). The TEIQue is comprised of four factors: well-being, self-control, emotionality, and sociability. Cronbach's alphas in the present study are 0.80 for well-being, 0.81 for self-control, 0.83 for emotionality, and 0.82 for sociability.

1.2.2.3. Compassion Scale (CS)

The Compassion Scale (Gu et al., 2017), translated into Italian by Di Fabio (2019), is composed of 22 items responded to on a 7-point Likert scale response format (1 = not at all true of me to 7 = completely true of me). The scale provides a total score and scores for five dimensions that include recognizing suffering, understanding the universality of suffering, emotional connection, tolerating uncomfortable feelings, and acting to help/alleviate suffering. The total score (alpha reliability coefficient = 0.83) was used in the present study.

1.2.2.4. Self-Compassion Scale (SCS)

The Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, 2003), translated into Italian by Di Fabio (2017b) includes 26 items answered on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = almost never to 5 = almost always). The six compassions dimensions assessed by the SCS include: self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. The total SCS scale with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.82 was used in the present study.

1.2.3. Procedure and data analysis

The questionnaires were administered to small groups by trained psychologists. The order of administration was counterbalanced to control the possible effects of presentation of the instruments. The instruments were administered according to the requirements of privacy and informed consent of Italian law. Descriptive statistics, Pearson's r correlations and hierarchical regressions were calculated.

1.3. Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between the BFQ, TEIQue-SF, CS, and SCS

are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between BFQ, TEIQue-SF, CS, and SCS.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BFQ Extraversion | 74.68 | 8.50 | _ | ||||||||||

| 2. BFQ Agreeableness | 82.35 | 9.73 | 0.16⁎ | _ | |||||||||

| 3. BFQ Conscientiousness | 81.13 | 9.50 | 0.22⁎ | 0.10 | _ | ||||||||

| 4. BFQ Emotional Stability | 72.43 | 12.84 | 0.24⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.14 | _ | |||||||

| 5. BFQ Openness | 84.25 | 8.81 | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.15⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | _ | ||||||

| 6. TEIQue Well-being | 32.41 | 6.35 | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.20⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.20⁎⁎ | _ | |||||

| 7. TEIQue Self-Control | 27.54 | 5.72 | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.24⁎⁎ | 0.12 | 0.59⁎⁎ | 0.20⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | _ | ||||

| 8. TEIQue Emotionality | 43.94 | 6.65 | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.12 | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.30⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | _ | |||

| 9. TEIQue Sociability | 27.80 | 5.40 | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.17⁎ | 0.24⁎⁎ | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | _ | ||

| 10. Compassion | 120.52 | 13.46 | 0.10 | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.17⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.62⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | _ | |

| 11. Self-compassion | 85.86 | 16.19 | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.69⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.40⁎⁎ | _ |

Note. N = 219.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Table 2 shows the results of hierarchical regression model with compassion as the dependent variable and the BFQ entered at the first step followed by the four dimensions of trait EI at the second step.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression. The contributions of personality traits BFQ (first step) and TEIQue dimensions (second step) to compassion.

| Compassion |

|

|---|---|

| β | |

| Step 1 | |

| BFQ Extraversion | 0.05 |

| BFQ Agreeableness | 0.49⁎⁎⁎ |

| BFQ Conscientiousness | 0.12 |

| BFQ Emotional Stability | 0.12 |

| BFQ Openness | 0.03 |

| Step 2 | |

| TEIQue Well-being | 0.13⁎ |

| TEIQue Self-Control | 0.15⁎ |

| TEIQue Emotionality | 0.43⁎⁎⁎ |

| TEIQue Sociability | 0.10 |

| R2 step 1 | 0.36⁎⁎⁎ |

| ∆R2 step 2 | 0.20⁎⁎⁎ |

| R2 total | 0.56⁎⁎⁎ |

Note. N = 219.

p < .05.

p < .001.

With regard to compassion, personality traits accounted for 36% of the variance at step one and the four dimensions of trait EI added a further 20%, accounting overall for 56% of the variance.

Table 3 shows the results of hierarchical regression model with self-compassion as dependent variable and with BFQ at the first step and the four dimensions of trait EI at the second step.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression. The contributions of personality traits BFQ (first step) and TEIQue dimensions (second step) to self-compassion.

| Self-compassion |

|

|---|---|

| β | |

| Step 1 | |

| BFQ Extraversion | 0.10 |

| BFQ Agreeableness | 0.18⁎ |

| BFQ Conscientiousness | 0.02 |

| BFQ Emotional Stability | 0.63⁎⁎⁎ |

| BFQ Openness | 0.02 |

| Step 2 | |

| TEIQue Well-being | 0.12⁎ |

| TEIQue Self-Control | 0.15⁎ |

| TEIQue Emotionality | 0.01 |

| TEIQue Sociability | 0.05 |

| R2step 1 | 0.52⁎⁎⁎ |

| ∆R2step 2 | 0.06⁎⁎⁎ |

| R2total | 0.58⁎⁎⁎ |

Note. N = 219.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Personality traits accounted for 52% of the variance in self-compassion at step one and the four dimensions of trait EI added only 6%, accounting overall for 58% of the variance.

1.4. Discussion

The present study examined the relationship between both compassion and self-compassion, personality traits (Big Five model) and trait EI dimensions including an analysis of the relationships of the combined effects of personality and trait EI.

Trait EI was significantly associated with compassion and added substantial incremental variance beyond personality. In particular, emotionality showed the strongest relationship with compassion indicating that individuals who are able to recognize and express their emotions (Petrides, 2009; Petrides & Furnham, 2001) also perceive themselves as more compassionate (Gu et al., 2017). Emotionality, together with the trait EI factors of self-control and well-being, appear to be a key factors underlying compassion in which we remain open to and accepting of another person's suffering, leading to being motivated to act to alleviate their condition (Di Fabio, 2019; Gu et al., 2017).

While EI did not account for a large amount of additional variance beyond personality traits in relation to self-compassion, self-control and well-being showed the strongest relationships. This suggests that managing one's own emotions (self-control) and having positive personal emotional strengths (well-being) (Petrides, 2009; Petrides & Furnham, 2001) may contribute to increased openness and sensitivity to one's own suffering, experiencing feelings of care and kindness to oneself, taking an attitude of understanding and not judging one's own inadequacies and failures, and recognizing that one's own experience is part of the common human experience (Di Fabio, 2017b; Neff, 2003).

1.5. Study 2

1.5.1. Aim and reearch questions

Following from the results obtained above, Study 2 further examined the relationship between personality, EI and compassion and self-compassion but focused on whether trait EI mediates these relationships. In relation to compassion, we hypothesized that: the trait EI dimensions of emotionality, self control and well-being will mediate the relationship between agreeableness and compassion, and that emotional stability will be positively correlated with both trait EI dimensions and self-compassion. For self-compassion, we predicted positive correlations with trait EI dimensions (self-control and well-being) and that trait EI dimensions (self-control and well-being) will mediate the relationship between emotional stability and self-compassion. We considered EI as a mediator in the relationships between personality traits and compassion and self-compassion because EI is amenable to training (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2011) in contrast to personality traits that are considered to be relatively stable (Costa & McCrae, 1992). As well, EI mediated compassion satisfaction (Valavanis, 2019) and showed consistent positive associations with criteria for well-being (Austin, Saklofske, & Egan, 2005).

1.6. Material and methods

1.6.1. Participants

Participants were 231 workers employed in Italian public organizations (57% men, 43% women). The participants ranged in age from 30 to 65 years (M = 45.02, SD = 8.22). The participation rate was 87%.

1.6.2. Measures

1.6.2.1. Big Five Questionnaire (BFQ)

To evaluate personality traits, the Big Five Questionnaire (BFQ; Caprara et al., 1993) was used as in Study 1. The Cronbach's alpha coefficients in the present study were 0.81 for extraversion, 0.80 for agreeableness, 0.79 for conscientiousness, 0.85 for emotional stability, 0.80 for openness.

1.6.2.2. Trait EI Questionnaire Short Form (TEIQue-SF)

The Trait EI Questionnaire Short Form (TEIQue-SF, Petrides, 2009), Italian version (Di Fabio and Palazzeschi (2011) was the same as used in Study 1. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient in the present study is 0.82 for well-being, 0.80 for self-control, 0.84 for emotionality, and 0.81 for sociability.

Compassion Scale (CS). To evaluate compassion, the Compassion Scale (Gu et al., 2017), the Italian version by Di Fabio (2019) was used as in Study 1. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient in the present study was 0.80.

1.6.2.3. Self-Compassion Scale (SCS)

The Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, 2003), Italian version by Di Fabio (2017b), used in Study 1, was again administered here. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient in the present study was 0.88.

1.6.3. Procedure and data analysis

The questionnaires were administered to small groups by trained psychologists. The order of administration was counterbalanced to control for the possible effects of presentation of the instruments. The instruments were administered according to the requirements of privacy and informed consent of Italian law.

Descriptive statistics, Pearson's r correlations and mediation analysis using the bootstrap method described by Hayes (2013) were carried out. A simple mediation model to assess the effects by which one independent variable is proposed to be associated a dependent variable through an intervening mediator variable.

1.7. Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for the BFQ, TEIQue-SF, CS, and SCS are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between BFQ, TEIQue-SF, CS, and SCS.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BFQ Extraversion | 64.61 | 7.46 | _ | ||||||||||

| 2. BFQ Agreeableness | 72.34 | 9.00 | 0.24⁎⁎ | _ | |||||||||

| 3. BFQ Conscientiousness | 71.14 | 8.94 | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | _ | ||||||||

| 4. BFQ Emotional Stability | 73.92 | 11.37 | 0.15⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.14 | _ | |||||||

| 5. BFQ Openness | 83.97 | 8.77 | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | _ | ||||||

| 6. TEIQue Well-being | 30.10 | 5.47 | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | _ | |||||

| 7. TEIQue Self-Control | 28.29 | 6.08 | 0.16⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.11 | 0.59⁎⁎ | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.40⁎⁎ | _ | ||||

| 8. TEIQue Emotionality | 44.15 | 6.58 | 0.30⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.17⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.54⁎⁎ | 0.40⁎⁎ | _ | |||

| 9. TEIQue Sociability | 29.36 | 6.54 | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | _ | ||

| 10. Compassion | 122.35 | 14.94 | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.57⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.57⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.64⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | _ | |

| 11. Self-compassion | 86.77 | 15.35 | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.11 | 0.66⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.61⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ | _ |

Note. N = 231.

p < .01.

p < .05.

The five personality factors were positively and significantly correlated with all TEIQue factors with one exception and also showed significant correlations with compassion and with one exception, self-compassion. For the TEIQue, emotionality (0.64), well-being (0.57), and self-control (0.48) showed significant correlations with compassion. Subsequently we performed three mediation analyses, using the personality trait of agreeableness as the independent variable, given that it had the highest correlation with compassion, and the three TEIQUE dimensions of emotionality, well-being and self-control as mediators, again because of their higher correlations with compassion.

Agreeableness was positively and directly associated with compassion and also indirectly associated with compassion through emotionality. As can be seen in Fig. 1 , participants who had higher agreeableness perceived themselves to have more emotionality (a = 0.37) and in turn, perceived also themselves to have more compassion (b = 0.96). A bias-corrected bootstraps confidence interval for the indirect effect (ab = 0.36) based on 5000 bootstrap samples was entirely above zero (0.25 to 0.50).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between agreeableness and compassion with TEIQUE dimensions of emotionality as mediator. R2 Mediator Effect Size = 0.24.

The effect of agreeableness on compassion was reduced after controlling for emotionality, but remained statistically significant (path c’ in Fig. 1; p < .001): these results therefore indicated a partial mediation model, with R2 = 0.24, p < .001).

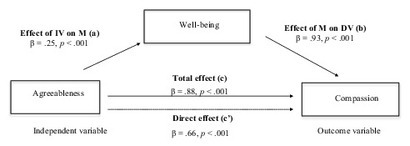

The second mediation model showed that agreeableness was positively and directly associated to compassion and also indirectly associated to compassion through well-being. Fig. 2 shows that participants who had higher agreeableness rated themselves higher on well-being (a = 0.25) and further, participants higher in self-reported well-being also rated themselves to be higher in compassion (b = 0.93). A bias-corrected bootstraps confidence interval for the indirect effect (ab = 0.23) based on 5000 bootstrap samples was entirely above zero (0.12 to 0.36). The effect of agreeableness on compassion was reduced after controlling well-being, although remaining significant (path c’ in Fig. 2; p < .001): these results therefore indicated a partial mediation model, with R2 = 0.17, p < .001).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between agreeableness and compassion with TEIQUE dimensions of well-being as mediator. R2 Mediator Effect Size = 0.17.

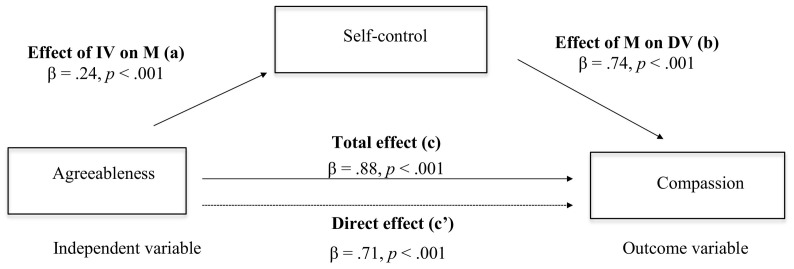

Thirdly, agreeableness was positively and directly associated to compassion and also indirectly associated to compassion through self-control. As shown in Fig. 3 , persons with higher agreeableness perceived themselves to have more self-control (a = 0.24) and participants who perceived themselves to have more self-control perceived also described themselves as higher in compassion (b = 0.74). A bias-corrected bootstraps confidence interval for the indirect effect (ab = 0.18) based on 5000 bootstrap samples was entirely above zero (0.11 to 0.28). The effect of agreeableness on compassion was reduced after controlling self-control, but again remained significant (path c’ in Fig. 3; p < .001): these results therefore indicated a partial mediation model, with R2 = 0.14, p < .001).

Fig. 3.

Relationship between agreeableness and compassion with TEIQUE dimensions of self-control as mediator. R2 Mediator Effect Size = 0.14.

Regarding self-compassion, among personality traits, emotional stability demonstrated significant and robust correlations with TEIQue dimensions and self-compassion, in comparison with lower or non-significant correlations for extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness. Among the TEIQue dimensions, self-control and well-being were most strongly related to self-compassion. This was followed by two mediation analyses, using the personality traits of emotional stability as the independent variables and the two TEIQUE dimensions of self-control and well-being as mediators.

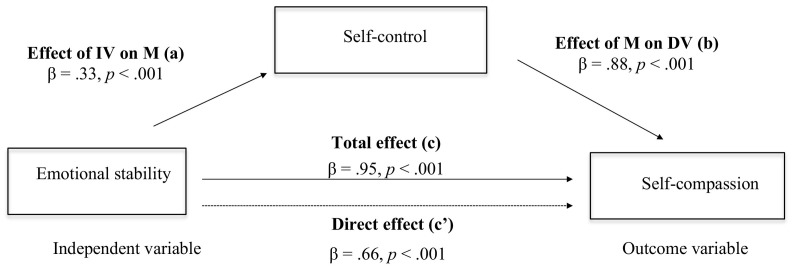

Emotional stability was positively and directly associated with self-compassion and also indirectly through self-control. Fig. 4 shows that participants with higher emotional stability view themselves as having more self-control (a = 0.33) and in turn, as feeling more self-compassion (b = 0.88). A bias-corrected bootstraps confidence interval for the indirect effect (ab = 0.29) based on 5000 bootstrap samples was entirely above zero (0.18 to 0.42). The effect of emotional stability on self-compassion was reduced after controlling self-control, although remaining significant (path c’ in Fig. 4; p < .001): these results therefore indicated a partial mediation model, with R2 = 0.31, p < .001).

Fig. 4.

Relationship between emotional stability and self-compassion with TEIQUE dimensions of self-control as mediator. R2 Mediator Effect Size = 0.31.

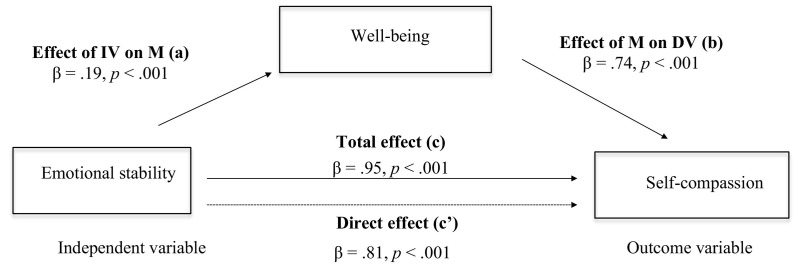

The second mediation model further showed that emotional stability was directly and positively associated to self-compassion as well as indirectly through well-being. Fig. 5 shows participants who had higher emotional stability rated themselves as having greater sense of more well-being (a = 0.19) who then further reported greater feelings of self-compassion (b = 0.74). A bias-corrected bootstraps confidence interval for the indirect effect (ab = 0.14) based on 5000 bootstrap samples was entirely above zero (0.08 to 0.21). The effect of emotional stability on self-compassion was reduced after controlling well-being, although remaining significant (path c’ in Fig. 5; p < .001): these results therefore indicated a partial mediation model, with R2 = 0.16, p < .001).

Fig. 5.

Relationship between emotional stability and self-compassion with TEIQUE dimensions of well-being as mediator. R2 Mediator Effect Size = 0.16.

1.8. Discussion

Study 2 extended previous research by testing mediation models examining the contribution of trait EI as a mediator of Big Five personality traits in relation to both compassion and self-compassion in workers public Italian organizations.

The link between agreeableness and compassion is in line with previous research (Goetz, 2008; Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997). The trait EI facets of emotionality, self-control, and well-being dimensions were positively correlated with compassion confirming the results obtained in Study 1. Furthermore, the relationship between agreeableness and compassion was mediated by emotionality; well-being and self-control results supported a partial mediation model see also Di Fabio, 2019; Gu et al., 2017). The interaction between agreeableness, emotionality and compassion is in line with recognizing emotions in self and others, being able to express emotions to others, and manifesting empathy and sharing fulfilling personal relationships (Petrides, 2009; Petrides & Furnham, 2001).

The findings of this study also supported previous research suggesting that emotional stability is associated with self-compassion (Arslan, 2016; Neff, 2003; Neff et al., 2007; Oral & Arslan, 2017; Thurackal et al., 2016) (H4). The trait EI facets of self-control and well-being were positively associated with self-compassion, confirming the results obtained in Study 1 and previous research (Heffernan et al., 2010; Neff, 2003; Şenyuva et al., 2014) (H5). Furthermore, the relationship between emotional stability and self compassion was mediated above all by self-control and the well-being EI facets, although the results indicated a partial mediation model. These findings highlight the promising contribution of trait EI dimensions, especially self-control, as a mediator between emotional stability and self-compassion (Di Fabio, 2017b; Neff, 2003).

2. General discussion

The two studies presented in this article have added to the reported relationships between personality traits, trait emotional intelligence (EI) and both compassion and self-compassion in two samples of Italian workers. Study 1 examined the relationships of both compassion and self-compassion with trait EI, controlling for the effects of the Big Five personality traits. Hierarchical regression analyses showed that trait EI (in particular, the emotionality dimension) accounted for variance in compassion beyond personality. Furthermore, trait EI and especially self-control explained a percentage of variance beyond that accounted for by personality traits in relation to self-compassion. Study 2 further verified that specific trait EI dimensions mediated the relationships between Big Five personality traits and both compassion and self-compassion. This study showed the promising contributions of the TEIQue dimension of emotionality in mediating the relationship between agreeableness and compassion, and of the TEIQue dimension of self-control in mediating the relationship between emotional stability and self-compassion. Taken together these findings show important contributions between the major individual differences constructs of EI and personality in relation both compassion and self-compassion. Such findings have particular relevance for building human capacity that includes desirable qualities such as compassion, which, in turn, has implications for our interactions with others as well as self-care. EI has been shown to be dynamic in the sense that it can be increased or enhanced (Vesely-Maillefer & Saklofske, 2018). In combination with personality factors such as agreeableness, EI factors including emotionality may be key in the development and manifestation of compassion. The ever increasing research findings and applications gleaned from positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005) have clearly shown the benefits to psychological health and well-being of individuals, organizations, and society. As shown in the literature review earlier in this paper, compassion and self-compassion must certainly be regarded as one of the central tenets of positive psychology.

Notwithstanding these promising results, it is necessary to note some limitations of the two studies reported here. The participants were Italian workers from the Tuscany region and thus future research should extend the study to workers from different geographical areas of Italy and other countries and also to include different target groups (e.g., unemployed, general population). Future studies should also consider demographics and background variables, for example gender, age and seniority at work as potential intervening factors. Future research could also explore relationships with other models of trait emotional intelligence (e.g., Bar-On, 1997) and ability-emotional intelligence l (Mayer & Salovey, 1997) as well also different personality models (e.g., Hexaco; Ashton & Lee, 2009).

In conclusion, these two studies add support to the role of trait emotional intelligence as an important and even primary factor in developing and promoting both compassion and self-compassion. Emotional intelligence education and training may be regarded as a key component in strength-based programs (Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014a, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2014b, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2018, Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2019) intended to support healthy organizations and workers (Di Fabio, 2017a; Peiró & Rodríguez, 2008; Tetrick & Peiró, 2012). And compassion would seem to be a most powerful human emotion and expression that has far reaching implications for the self, others and the world we live in.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Annamaria Di Fabio:Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Donald H. Saklofske:Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

References

- Abendroth M. Compassion fatigue: Caregivers at risk. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2011;16(1) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01OS01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmet A.K.I.N. Self-compassion and achievement goals: A structural equation modeling approach. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research. 2008;31:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Alkema K., Linton J.M., Davies R. A study of the relationship between self-care, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout among hospice professionals. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care. 2008;4(2):101–119. doi: 10.1080/15524250802353934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan B.A., Duffy R.D., Douglass R. Meaning in life and work: A developmental perspective. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2015;10(4):323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan C. Interpersonal problem solving, self-compassion and personality traits in university students. Educational Research and Reviews. 2016;11(7):474–481. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton M.C., Lee K. The HEXACO–60: A short measure of the major dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91(4):340–345. doi: 10.1080/00223890902935878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin E.J., Saklofske D.H., Egan V. Personality, well-being and health correlates of trait emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38(3):547–558. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard L.K., Curry J.F. Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology. 2011;15(4):289–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On R. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, ON, Canada: 1997. The emotional intelligence inventory (EQ-I): Technical manual. [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais A., Andreychik M., Henkel L.A. The role of emotional intelligence and empathy in compassionate nursing care. Mindfulness & Compassion. 2017;2(2):92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bento R.F. When the show must go on. Disenfranchised grief in organizations. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 1994;9(6):35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein D.L. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. The psychology of working: A new perspective for career development, counseling, and public policy. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein D.L. A relational theory of working. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2011;79(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein D.L., Kenny M.E., Di Fabio A., Guichard J. Expanding the impact of the psychology of working: Engaging psychology in the struggle for decent work and human rights. Journal of Career Assessment. 2019;27:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bluth K., Neff K.D. New frontiers in understanding the benefits of self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2018;17(6):605–608. [Google Scholar]

- Brody H. Assisted death—A compassionate response to a medical failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;327(19):1384–1388. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211053271912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara G.V., Barbaranelli C., Borgogni L. 2nd ed. Giunti O.S; Firenze, Italy: 1993. BFQ: Big Five Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell E.J. Compassion. In: Snyder C.R., Lopez S.J., editors. Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 434–445. [Google Scholar]

- Chu L.C. Impact of providing compassion on job performance and mental health: The moderating effect of interpersonal relationship quality. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2017;49(4):456–465. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon P. Mindfulness, compassion, and prosocial behaviour. In: Karremans J.C., Papies E.K., editors. Mindfulness in social psychology. Psychology Press; Hove, UK: 2017. pp. 132–146. [Google Scholar]

- Costa P.T., McCrae R.R. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odesssa, FL: 1992. NEO personality inventory-revised (NEO-PI-R) and neo five factor inventory (NEO-FFI) Profesional manual. [Google Scholar]

- Dafeeah E.E., Eltohami A.A., Ghuloum S. Emotional intelligence and attitudes toward HIV/AIDS patients among healthcare professionals in the State of Qatar. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation. 2015;4(1):19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dev V., Fernando A.T., III, Lim A.G., Consedine N.S. Does self-compassion mitigate the relationship between burnout and barriers to compassion? A cross-sectional quantitative study of 799 nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2018;81:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A. Positive healthy organizations: Promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. In: Arcangeli G., Giorgi G., Mucci N., Bernaud J.-L., Di Fabio A., editors. Emerging and re-emerging organizational features, work transitions and occupational risk factors: The good, the bad, the right. An interdisciplinary perspective. Vol. 8. 2017. p. 1938. (Research topic in Frontiers in Psychology. Organizational Psychology). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A. Self-Compassion Scale: Primo contributo alla validazione della versione italiana [Self-Compassion Scale: First study for the validation of the Italian version] Counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni. 2017;10(2) doi: 10.14605/CS1021705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A. Compassion scale: proprietà psicometriche della versione italiana [compassion scale: Psychometric properties of the Italian version] Counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni. 2019;12(1) doi: 10.14605/CS1211908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Kenny M.E. Promoting emotional intelligence and career decision making among Italian high school students. Journal of Career Assessment. 2011;19:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Kenny M.E. The contributions of emotional intelligence and social support for adaptive career progress among Italian youth. Journal of Career Development. 2015;42:48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Kenny M.E. From decent work to decent lives: Positive self and relational management (PS&RM) in the twenty-first century. In: Di Fabio A., Blustein D.L., editors. From meaning of working to meaningful lives: The challenges of expanding decent work. Vol. 7. 2016. p. 361. (Research topic in Frontiers in Psychology.Section Organizational Psychology). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Kenny M.E. Promoting well-being: The contribution of emotional intelligence. In: Giorgi G., Shoss M., Di Fabio A., editors. From organizational welfare to business success: Higher performance in healthy organizational environments. Vol. 7. 2016. p. 1182. (Research topic in Frontiers in Psychology. Organizational Psychology). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Kenny M.E. Academic relational civility as a key resource for sustaining well-being. In: Di Fabio A., editor. Psychology of sustainability and sustainable development. Special issue in Sustainability MDPI. Vol. 10(6) 2018. p. 1914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Kenny M.E. 2019. Resources for enhancing employee and organizational well-being beyond personality traits: The promise of emotional intelligence and positive relational management. Personality and Individual Differences (special issue personality, individual differences and healthy organizations) p. 151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Palazzeschi L. Proprietà psicometriche del Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire Short Form (TEIQue-SF) nel contesto italiano[psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire Short Form (TEIQue-SF) in the Italian context] Counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni. 2011;4:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Rosen M.A. Opening the black box of psychological processes in the science of sustainable development: A new frontier. European Journal of Sustainable Development Research. 2018;2(4):47. doi: 10.20897/ejosdr/3933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Saklofske D.H. Comparing ability and self-report trait emotional intelligence, fluid intelligence, and personality traits in career decision. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;64:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Saklofske D.H. Promoting individual resources: The challenge of trait emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;65:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Saklofske D.H. The contributions of personality and emotional intelligence to resiliency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2018;123:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A., Saklofske D.H. Positive relational Management for Sustainable Development: Beyond personality traits - the contribution of emotional intelligence. In: Di Fabio A., editor. Psychology of sustainability and sustainable development. Special issue in Sustainability MDPI. Vol. 11(2) 2019. p. 330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doka K.J. Lexington Books; Lexington, MA: 1989. Disenfranchised grief: Recognizing hidden sorrow. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy R.D., Blustein D.L., Diemer M.A., Autin K.L. The psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2016;63(2):127–148. doi: 10.1037/cou0000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J.E., Frost P.J., Worline M.C., Lilius J.M., Kanov J.M. Leading in times of trauma. Harvard Business Review. 2002;80(1):54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J.E., Worline M.C., Frost P.J., Lilius J. Explaining compassion organizing. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2006;51(1):59–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J.E., Lilius J.M., Kanov J.M. The transformative potential of compassion at work. In: Piderit S.K., Fry R.E., Cooperrider D.L., editors. Handbook of transformative cooperation: New designs and dynamics. Stanford Univ. Press; Stanford, CA: 2007. pp. 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J.E., Workman K.M., Hardin A.E. Compassion at work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2014;1(1):277–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eldor L. Public service sector: The compassionate workplace—The effect of compassion and stress on employee engagement, burnout, and performance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2018;28(1):86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Frost P.J. Harvard Bus. School Press; Boston: 2003. Toxic emotions at work: How compassionate managers handle pain and conflict. [Google Scholar]

- Frost P.J., Dutton J.E., Worline M.C., Wilson A. Narratives of compassion in organizations. Emotion in Organizations. 2000;2:25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz J.L. University of California; Berkeley: 2008. Compassion as a discrete emotion: Its form and function. [Google Scholar]

- Grant A.M., Dutton J.E., Rosso B.D. Giving commitment: Employee support programs and the prosocial sensemaking process. Academy of Management Journal. 2008;51(5):898–918. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano W.G., Eisenberg N.H. Agreeableness: A dimension of personality. In: Hogan R., Johnson J., Briggs S., editors. Handbook of personality psychology. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1997. pp. 795–824. [Google Scholar]

- Gu J., Cavanagh K., Baer R., Strauss C. An empirical examination of the factor structure of compassion. PLoS One. 2017;12(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The moral emotions. In: Davidson R.J., Scherer K.R., Goldsmith H.H., editors. Handbook of affective sciences. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 852–870. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan M., Quinn Griffin M.T., McNulty S.R., Fitzpatrick J.J. Self-compassion and emotional intelligence in nurses. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2010;16(4):366–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Yeom H.A. The association between spiritual well-being and burnout in intensive care unit nurses: A descriptive study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2018;46:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.H., Kim S.R., Kim Y.O., Kim J.Y., Kim H.K., Kim H.Y. Influence of type D personality on job stress and job satisfaction in clinical nurses: The mediating effects of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2017;73(4):905–916. doi: 10.1111/jan.13177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimecki O.M., Leiberg S., Lamm C., Singer T. Functional neural plasticity and associated changes in positive affect after compassion training. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;23:1552–1561. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilius J.M., Worline M.C., Maitlis S., Kanov J., Dutton J.E., Frost P. The contours and consequences of compassion at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2008;29(2):193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay E.K., Creswell J.D. Helping the self help others: Self-affirmation increases self-compassion and pro-social behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:421. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López A., Sanderman R., Ranchor A.V., Schroevers M.J. Compassion for others and self-compassion: Levels, correlates, and relationship with psychological well-being. Mindfulness. 2018;9(1):325–331. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0777-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon S.R., Trotter F., Holt B., Powell E., Roe A. Emotional intelligence and its role in recruitment of nursing students. Nursing Standard. 2013;27(40):41–46. doi: 10.7748/ns2013.06.27.40.41.e7529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBeth A., Gumley A. Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S.L., Ciarrochi J., Parker P.D., Sahdra B.K. Is self-compassion selfish? The development of self-compassion, empathy, and prosocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2019 doi: 10.1111/jora.12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer J.D., Salovey P. What is emotional intelligence? In: Salovey P., Sluyter D., editors. Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications. Basic Books; New York, CA: 1997. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer J.D., Salovey P., Caruso D.R. Selecting a measure of emotional intelligence: The case of ability scales. In: Bar-On R., Parker J.D., editors. The handbook of emotional intelligence. Jossey Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2000. pp. 320–342. [Google Scholar]

- Melwani S., Mueller J.S., Overbeck J.R. Looking down: The influence of contempt and compassion on emergent leadership categorizations. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2012;97(6):1171–1185. doi: 10.1037/a0030074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwanje S.P. Makerere university business school Institutional repository; 2018. Organisational compassion, happiness at work and employee engagement in selected HIV/AIDS programme focused organisations. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Neff K.D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003;2(3):223–250. [Google Scholar]

- Neff K.D., Hsieh Y.P., Dejitterat K. Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and Identity. 2005;4(3):263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Neff K.D., Knox M.C. Self-compassion. In: Zeigler-Hill V., Shackelford T.K., editors. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Springer; Cham: 2017. pp. 1–8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff K.D., Rude S.S., Kirkpatrick K.L. An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(4):908–916. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale S., Spiby H., Sheen K., Slade P. The impact of emotional intelligence in health care professionals on caring behaviour towards patients in clinical and long-term care settings: Findings from an integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2018;80:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral T., Arslan C. The investigation of university students’ forgiveness levels in terms of self-compassion, rumination and personality traits. Universal Journal of Educational Research. 2017;5(9):1447–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Peiró J.M. Stress and coping at work: New research trends and their implications for practice. In: Näswall K., Hellgren J., Sverke M., editors. The individual in the changing working life. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2008. pp. 284–310. [Google Scholar]

- Peiró J.M., Bayonab J.A., Caballer A., Di Fabio A. PAID 40th anniversary special issue. Personality and individual differences. 2020. Importance of work characteristics affects job performance: The mediating role of individual dispositions on the work design-performance relationships; p. 157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peiró J.M., Rodríguez I. Work stress, leadership and organizational health. Papeles del Psicólogo. 2008;29(1):68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Peiró J.M., Sora B., Caballer A. Job insecurity in the younger Spanish workforce: Causes and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2012;80(2):444–453. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides K.V. Psychometric properties of the trait EI questionnaire. In: Stough C., Saklofske D.H., Parker J.D., editors. Advances in the assessment of EI. Springer; New York: 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides K.V., Furnham A. Trait EI: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality. 2001;15:425–428. [Google Scholar]

- Reizer A. Bringing self-kindness into the workplace: Exploring the mediating role of self-compassion in the associations between attachment and organizational outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan J.D., Fry B.N., Steenbergh T.A., Arbuckle N.L., Dunbar K., Devers E.E. Using experience sampling to examine links between compassion, eudaimonia, and pro-social behavior. Journal of Personality. 2019;87(3):690–701. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M.E.P., Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M.E.P., Steen T.A., Park N., Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist. 2005;60(5):410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şenyuva E., Kaya H., Işik B., Bodur G. Relationship between self-compassion and emotional intelligence in nursing students. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2014;20(6):588–596. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppala E., Rossomando T., Doty J.R. Social connection and compassion: Important predictors of health and well-being. Social Research: An International Quarterly. 2013;80(2):411–430. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm B.H. Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the compassion satisfaction and fatigue test. In: Figley C.R., editor. Treating compassion fatigue. Brunner-Routledge; New York: 2002. pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Stough C., Saklofske D., Parker J. Springer; New York: 2009. Assessing EI: Theory, research, and applications. [Google Scholar]

- Tetrick L.E., Peiró J.M. The Oxford handbook of organizational psychology. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2012. Occupational safety and health. [Google Scholar]

- Thurackal J.T., Corveleyn J., Dezutter J. Personality and self-compassion: Exploring their relationship in an Indian context. European Journal of Mental Health. 2016;11:18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Valavanis S. Lancaster University; 2019. The relationships between nurses’ emotional intelligence, attachment style, burnout, compassion and stigma. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Vesely A.K., Saklofske D.H., Nordstokke D.W. EI training and pre-service teacher wellbeing. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;65:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Vesely-Maillefer A.K., Saklofske D.H. Emotional intelligence in education. Springer; Cham: 2018. Emotional intelligence and the next generation of teachers; pp. 377–402. [Google Scholar]

- Worline M., Dutton J.E. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; Oakland, CA: 2017. Awakening compassion at work: The quiet power that elevates people and organizations. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Guo Z., Kou Y., Liu B. Linking self-compassion and Prosocial behavior in adolescents: The mediating roles of relatedness and trust. Child Indicators Research. 2019;12:2035–2049. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidner M., Hadar D., Matthews G., Roberts R.D. Personal factors related to compassion fatigue in health professionals. Anxiety, Stress & Coping. 2013;26(6):595–609. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.777045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zessin U., Dickhäuser O., Garbade S. The relationship between self-compassion and well-being: A meta-analysis. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2015;7(3):340–364. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]