Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the greatest infectious challenges in recent history. Presently, few treatment options exist and the availability of effective vaccines is at least one year away. There is an urgent need to find currently available, effective therapies in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 infection. In this review, we compare and contrast the use of intravenous immunoglobulin and hyperimmune globulin in the treatment of COVID-19 infection.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Coronavirus, Intravenous immunoglobulin, Hyperimmune globulin

Abbreviations: COVID-19, Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoronaVirus-2; MERS, Middle East Respiratory syndrome; IVIG, intravenous Immunoglobulin; S protein, spike protein; RBD, eceptor binding domain; ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; ADE, antibody dependent enhancement; ALI, acute lung injury; DAD, diffuse alveolar damage

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), poses an unprecedented challenge to clinicians and strain on the healthcare system due to its high rate of infectivity (Ro) and mortality. Currently, there is no consensus on treatment algorithms for COVID-19, as the evidence available is not well controlled and largely anecdotal. Given rapid and catastrophic spread of COVID-19, there is an urgent need to explore pre-existing therapeutic options while novel therapies and vaccines are being developed. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is a product derived from the plasma of thousands of donors used for treatment of primary and secondary immunodeficiencies, autoimmune/inflammatory conditions, neuroimmunologic disorders, and infection-related sequelae. IVIG provides passive immune protection against a broad range of pathogens. Hyperimmune globulin, in contrast, is derived from individuals with high antibody titers to specific pathogens and has been used successfully in the treatment of infections, such as cytomegalovirus and H1N1 influenza. Here, we review the mechanism and utility of IVIG and hyperimmune globulin in viral infections, and consider their usage in COVID-19 infection (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Comparison of Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) vs. Hyperimmune Sera.

| Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) | Hyperimmune sera | |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation |

|

|

| Donors |

|

|

| Usage |

|

|

| Benefits |

|

|

| Limitations |

|

|

| Rationale for use in COVID-19 |

|

|

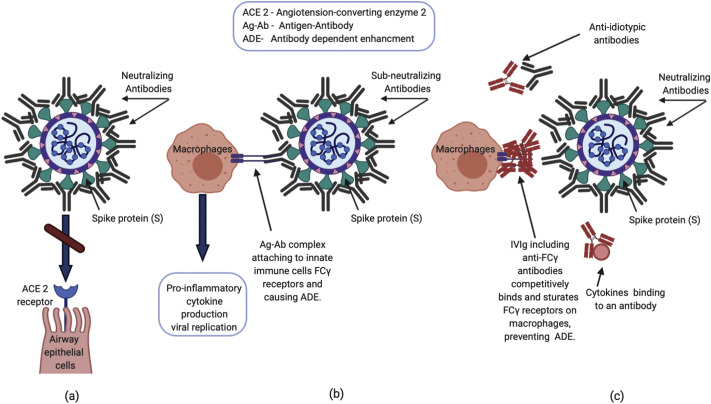

2. Viral binding to host cells

The entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells is mediated by the transmembrane spike (S) glycoprotein that binds to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is highly expressed on the apical surface of many cell types, including airway epithelial cells. The S protein forms a homotrimer that protrudes from the viral surface. Receptor binding is mediated by the S1 subunit through the receptor binding domain (RBD). After binding to the ACE2 receptor, proteolytic activation of the S2 subunit mediates the fusion between the viral and the cellular membranes [1]. Due to the essential role of S glycoprotein in cellular infection, antibodies that bind to S1 and S2 can prevent infection (Fig. 1 ), as demonstrated in cell cultures by incubating virus in the presence of neutralizing antibody and quantitating reduction in viral intracellular RNA levels [2]. A neutralizing antibody can stop viral replication by blocking receptor binding, preventing wall fusion, or preventing uncoating of the virus once inside the cytoplasm.

Fig. 1.

Proposed mechanisms of neutralizing antibodies and IVIG in COVID-19 infection.

(a) Neutralizing antibodies prevent SARS-CoV2 spike protein from attaching to the ACE2 receptor, inhibiting viral entry into the cell. (b) Immune complexes consisting of viral antigens and anti-viral sub-neutralizing antibodies can activate Fcγ receptors on innate immune cells (e.g. macrophages) in the lung, triggering an exaggerated inflammatory response leading to acute lung injury via antibody dependent enhancement (ADE). Additionally, antibody-bound virus can be internalized through Fcγ receptors, enhancing viral replication. (c) Proposed mechanisms whereby IVIG exerts anti-inflammatory action include saturation of Fcγ receptor binding, anti-idiotypic binding to anti-viral antibodies, and binding of proinflammatory cytokines.

3. Humoral response in SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2

Analyses of patients infected with SARS-CoV has revealed seroconversion four days following disease onset in some individuals and the majority of patients seroconverted between two to three weeks of disease onset in patients infected with either SARS-CoV or Middle East Respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) [3,4]. Weak or delayed antibody responses were associated with poor outcomes. Analysis of SARS-CoV convalescent human plasma revealed that SARS-neutralizing antibodies peaked at four months post recovery, but were undetectable in 16% of patients at 36 months. Evaluation of serum from MERS-CoV patients demonstrated that high antibody titers against MERS-CoV were only likely to be present in patients who had severe disease and those titers waned within six months following recovery. Mild or asymptomatic patients with MERS exhibited no serologic response [4]. These observations demonstrate the importance of verifying high antibody titers in potential convalescent serum donors. Some cross-reactivity was observed in five patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection with SARS-CoV in vitro, but not with other coronaviruses, suggesting that convalescent plasma used to treat SARS-CoV-2 will ideally be obtained from COVID-19 survivors.

Emerging studies have begun to characterize the antibody response seen in patients with COVID-19. To et al. evaluated serum antibody responses in 23 SARS-CoV-2 patients in Hong Kong. The majority of patients were positive for anti-RBD IgG 10 days after symptom onset and 100% of patients were positive for anti-RBD IgG 14 days following symptom onset. Severe disease was associated with earlier production and higher titer of anti-RBD IgG [5]. More recently, the kinetics of immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection were described in 285 patients with COVID-19. In this cohort, the median time required for the development of anti-viral IgG and IgM was 13 days after the start of symptoms, and all patients developed anti-viral IgG within 19 days [6]. While there was over a four-fold log difference found in the anti-viral IgG levels among patients, there was no correlation between anti-viral IgG levels and clinical outcome measures (lymphocyte numbers, C reactive protein levels, or duration of hospitalization) [6]. As neutralization activity of the anti-viral antibodies was not tested, variability in antibody effectiveness may have contributed to the lack of correlation between anti-viral IgG and clinical outcomes [6]. The use of seroconversion as a biomarker of acquired anti-viral immunity requires determination of the antibody levels indicative of prior infection [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. Serial antibody testing during the course of COVID-19 infection in 41 patients within this cohort revealed that 71% either seroconverted or demonstrated a four-fold increase in IgG-specific antibody titers, meeting the established criteria for serologic evidence of MERS-CoV infection [6]. As it is infeasible to test all individuals throughout the course of COVID-19, further evaluation of immune responses in asymptomatic, mild, and severe SARS-CoV-2-infected patients will be needed to quantify the levels and persistence of antibody titers that confer anti-viral immunity.

Recently, Quniti and colleagues in Italy have reported their experience with COVID-19 infection in seven patients with primary immunodeficiency, two with X-linked agammaglobulinemia and five with common variable immune deficiency (CVID), genetic diagnoses unknown (Article in Press, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.013). All patients were maintained on IVIG. Interestingly, both agammaglobulinemia patients had mild disease of short duration. In contrast, all five CVID patient had more severe, prolonged COVID-19 infection with four patients requiring mechanical ventilation and one death. CVID patients were noted to have more comorbidities. Although the experience is quite limited, the milder course in the agammaglobulinemia patients suggests antibodies or B cells may aggravate COVID-19 infection. Alternatively, CVID is generally associated with more severe immune deficiency than X-linked agammaglobulinemia and variable B and T cell defects, suggesting a critical role for cellular immunity against COVID-19. As will be discussed below, the presence of anti-viral antibodies can be associated with exacerbation of disease.

4. Efficacy of IVIG in the treatment of viruses

IVIG was first licensed in the United States in 1980 and is a highly effective therapy for the prevention of life-threatening infections in patients with primary and secondary immune deficiencies (Table 1). IVIG has been used to treat chronic infections, such as parvovirus infection complicated by anemia. Presently, experience with the use of IVIG in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection is very limited. The rationale for the use of IVIG in SARS-CoV-2 infection is modulation of inflammation. Several anti-inflammatory mechanisms of IVIG may lessen the inflammatory response in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, including the presence autoreactive antibodies that bind cytokines or binding to the variable domains of other antibodies (anti-idiotypic antibodies)(Fig. 1). Additionally, the presence of IgG dimers in IVIG may block activating FcγR on innate immune effector cells [11](Fig. 1). There is a case series on IVIG usage in three SARS-CoV-2 patients in China. All 3 patients were classified as severe, and all had lymphopenia with elevated inflammatory markers. The patients received IVIG at 0.3–0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days. They all had normalization of temperature within two days of treatment, and alleviation of respiratory symptoms within five days. Confounding factors include the concurrent usage of antivirals in two of the three patients and steroids in one patient, as well as the lack of case-matched control patients [12]. While the recovery of these patients is encouraging, it is important to consider the difficulty of performing adequately controlled studies in the early days of a deadly pandemic.

The use of IVIG has been reported in the treatment of other coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV. A systematic review of treatment effects in SARS patients, including IVIG or convalescent plasma, has been reported. Five studies of the use of IVIG or convalescent plasma given in addition to corticosteroids and ribavirin were evaluated. These studies were deemed inconclusive since the effects of IVIG or convalescent plasma could not be distinguished from other factors that included comorbidities, stage of illness, and the effect of other treatments [13]. In a single-center prospective study of SARS infection in Taiwan, IVIG was administered for leukopenia or thrombocytopenia, or if there was rapid progression of disease on radiography. A total of 40 patients received IVIG, of whom 22 had severe cytopenias, with one patient having evidence of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The study suggests that IVIG led to significant improvement in leukocyte and platelet counts, but acknowledges that there was no control group to objectively evaluate responses [14]. A single center retrospective study in Singapore found that adult SARS patients treated with a regimen of pulse methylprednisolone (400 mg) and IVIG (0.4 mg/kg) daily for three consecutive days had an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.41 for mortality compared to the untreated group, with a trend towards earlier recovery. However, this finding was not statistically significant (95% CI 0.14–1.23; P = .11). Furthermore, this result was confounded by the concurrent use of steroids [15]. There are two case reports of IVIG used in MERS. One patient received IVIG with high-dose corticosteroids due to thrombocytopenia, with resulting improvement in platelet count. Similar to the previous study, there was concurrent steroid use and, moreover, the patient's overall clinical course is unknown [16]. Thus, the field lacks strong evidence to support the use of IVIG for the treatment of coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS.

5. Efficacy of hyperimmune globulin in the treatment of viruses

More robust evidence exists for the use of hyperimmune globulin in the treatment viral illnesses (Table 1). A retrospective review revealed that convalescent plasma from SARS-CoV survivors administered to SARS-CoV patients with progressive disease resulted in significantly higher discharge rates at day 22 and lower mortality rates, compared to historical controls [17]. In 2009, a prospective cohort study on the effectiveness of convalescent plasma from H1N1 survivors with a titer of ≥1:160 offered to ICU patients with severe H1N1 infection was undertaken. Patients that refused convalescent plasma infusions were controls. Twenty of the 93 patients received convalescent sera. Treatment with convalescent plasma led to significantly reduced respiratory viral load, serum cytokine levels (IL-6, IL-10, TNFα), and mortality [18]. One study compared the effectiveness of hyperimmune globulin from convalescent plasma from H1N1 survivors versus IVIG in H1N1 patients in an ICU on respiratory support and receiving oseltamivir. This study was a prospective, double blind, randomized controlled study which demonstrated reduced a viral load and increased survival in the group receiving hyperimmune globulin. This study demonstrated the superiority of hyperimmune globulin over IVIG in treatment of severe H1N1 infection [19].

6. Pitfalls in the development of anti-viral antibodies

While antibodies against coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 play an important role in host defense against these infections, there is concern that antibodies can trigger a harmful, exaggerated inflammatory response in a process termed antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) (Fig. 1). Previously, ADE has been proposed as an underlying pathogenic mechanism in Dengue hemorrhagic fever. Pre-existing, subneutralizing antibodies form immune complexes with virus which bind to FcγR-bearing cells, leading to increased viral uptake and replication [20]. Similarly, antibodies against the S protein of a coronavirus may facilitate entry into host cells, likely through the FcγR, resulting in increased viral loads. Wan et al. demonstrated that a monoclonal antibody (mAb) against MERS-CoV can bind viral S protein, inducing a conformational change that promotes proteolytic activation of the S protein and viral entry. Further, the mAb was also able to mediate viral entry through uptake by FcγR [21]. Recently, animal models evaluating SARS-CoV infection in macaques has demonstrated that antibodies against the S protein can activate FcγR in M2 macrophages in the lung, triggering an exaggerated inflammatory response with the release of large quantities of IL-6 and IL-8, recruitment of inflammatory cells to the lung, leading to acute lung injury (ALI), diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) and death [22]. This model recapitulates the lung damage observed in lung tissue of deceased SARS-infected patients. In fact, plasma derived from these patients has been shown to trigger release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from macrophages. This process was blocked using anti-FcγR antibodies, implicating this FcγR-mediated pathway in ALI and DAD. Plasma that elicit ADE-induced inflammation was found to be present in patients with earlier onset of production of SARS-CoV IgG and more severe clinical courses.

7. Potential strategies and future studies needed

The COVID-19 pandemic represents one of the most widespread infectious challenges in recent times. As of the time of this publication, COVID-19 is responsible for greater than 250,000 deaths worldwide and the count continues to increase on a daily basis. The search for effective antiviral therapies and treatment is ongoing. Vaccine development is progressing at a rapid pace, but widespread vaccine availability is estimated to be at least one year away. There is an urgent need for effective interventions presently. Performing a randomized controlled trial with a placebo arm in the midst of a deadly pandemic is extremely challenging. Until herd immunity develops against SARS-CoV-2, preferably by means of effective vaccines, the global population will remain at risk. Past experience has demonstrated that vaccine development needs to be performed cautiously to avoid potential exacerbation of disease (i.e. ADE). Use of hyperimmune globulin has demonstrated clear effectiveness in the treatment of influenza and SARS-CoV. However, plasma must be collected and processed from convalescent patients and verified to have adequate titers. Based upon experience with SARS-CoV, plasma should ideally be collected from patients with a milder course of illness without symptoms consistent with ADE (i.e. respiratory distress). Although data for the use of IVIG in SARS and MERS infection is weak, high dose IVIG may be helpful in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection through immune modulation, saturating FcγR and reducing ADE (Fig. 1). Clearly, the use of immunoglobulins in the treatment of COVID-19 is effective, but not without potential adverse consequence (Table 1). Clear demonstration of therapeutic benefit will require well controlled studies.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CAPSULE SUMMARY: Immunoglobulins, including intravenous immunoglobulin and convalescent plasma, have potential uses and limitations in the treatment of COVID-19 infection.

Footnotes

Supported by: 5T32AI00751234(A.A.N.), 1K08AI116979-01 (J.S.C.), Eleanor and Miles Shore 50th Anniversary Fellowship Award (C.D.P.), 1R01AI139633-01(R.S.G.) the Samara Turkel Foundation and the Perkin Fund (R.S.G).

References

- 1.Walls A.C., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. (e6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ter Meulen J., van den Brink E.N., Poon L.L., Marissen W.E., Leung C.S., Cox F. Human monoclonal antibody combination against SARS coronavirus: synergy and coverage of escape mutants. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prompetchara E., Ketloy C., Palaga T. Immune responses in COVID-19 and potential vaccines: lessons learned from SARS and MERS epidemic. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2020;38(1):1–9. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choe P.G., Perera R., Park W.B., Song K.H., Bang J.H., Kim E.S. MERS-CoV antibody responses 1 year after symptom onset, South Korea, 2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23(7):1079–1084. doi: 10.3201/eid2307.170310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.To KK, Tsang O.T., Leung W.S., Tam A.R., Wu T.C., Lung D.C. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long Q.X., Liu B.Z., Deng H.J., Wu G.C., Deng K., Chen Y.K. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keitel W.A., Voronca D.C., Atmar R.L., Paust S., Hill H., Wolff M.C. Effect of recent seasonal influenza vaccination on serum antibody responses to candidate pandemic influenza a/H5N1 vaccines: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2019;37(37):5535–5543. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tout I., Loureiro D., Mansouri A., Soumelis V., Boyer N., Asselah T. Hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance: immune mechanisms, clinical impact, importance for drug development. J. Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.013. pii: S0168-8278(20)30225-7, [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bissett S.L., Godi A., Jit M., Beddows S. Seropositivity to non-vaccine incorporated genotypes induced by the bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2017;35(32):3922–3929. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cagigi A., Cotugno N., Rinaldi S., Santilli V., Rossi P., Palma P. Downfall of the current antibody correlates of influenza vaccine response in yearly vaccinated subjects: toward qualitative rather than quantitative assays. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(1):22–27. doi: 10.1111/pai.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwab I., Nimmerjahn F. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: how does IgG modulate the immune system? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13(3):176–189. doi: 10.1038/nri3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao W., Liu X., Bai T., Fan H., Hong K., Song H. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin as a therapeutic option for deteriorating patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(3):ofaa102. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stockman L.J., Bellamy R., Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J.T., Sheng W.H., Fang C.T., Chen Y.C., Wang J.L., Yu C.J. Clinical manifestations, laboratory findings, and treatment outcomes of SARS patients. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10(5):818–824. doi: 10.3201/eid1005.030640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lew T.W., Kwek T.K., Tai D., Earnest A., Loo S., Singh K. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. JAMA. 2003;290(3):374–380. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arabi Y.M., Hajeer A.H., Luke T., Raviprakash K., Balkhy H., Johani S. Feasibility of using convalescent plasma immunotherapy for MERS-CoV infection, Saudi Arabia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016;22(9):1554–1561. doi: 10.3201/eid2209.151164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng Y., Wong R., Soo Y.O., Wong W.S., Lee C.K., Ng M.H. Use of convalescent plasma therapy in SARS patients in Hong Kong. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2005;24(1):44–46. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung I.F., To KK, Lee C.K., Lee K.L., Chan K., Yan W.W. Convalescent plasma treatment reduced mortality in patients with severe pandemic influenza a (H1N1) 2009 virus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52(4):447–456. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung I.F.N., To KKW, Lee C.K., Lee K.L., Yan W.W., Chan K. Hyperimmune IV immunoglobulin treatment: a multicenter double-blind randomized controlled trial for patients with severe 2009 influenza a(H1N1) infection. Chest. 2013;144(2):464–473. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murrell S., Wu S.C., Butler M. Review of dengue virus and the development of a vaccine. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011;29(2):239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan Y., Shang J., Sun S., Tai W., Chen J., Geng Q. Molecular mechanism for antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus entry. J. Virol. 2020;94(5) doi: 10.1128/JVI.02015-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L., Wei Q., Lin Q., Fang J., Wang H., Kwok H. Anti-spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI Insight. 2019;4(4) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]