There seems to be no end in sight to the coronavirus crisis in Spain yet, and each day more people are becoming infected and are losing their lives due to the epidemic outbreak caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Spain currently has the second-highest number of cases in the world after the United States.

All healthcare professionals should employ additional protective measures (masks, goggles, and special protective screens) to treat COVID-19 patients. The use of this equipment for long time periods can cause skin pressure discomfort and injuries, making it essential to take all available measures to protect the skin areas that may be affected and prevent this type of injury (Fig. 1 ). This is compounded by the fact that due to the high number of patients seen in hospitals, healthcare workers must work with these protection measures continuously in place for upwards of 4–5 hours on a daily basis, especially in the case of nursing staff.

Fig. 1.

A distinctive red line can be seen on this nurse's forehead from where her protective equipment pressed down on her face, and an erythematous zone in the nasal dorsum.

Hydrocolloid is semi-permeable material that is present as a layer within a film or foam pad which adheres to the skin, usually used for wound healing. A hydrocolloid dressing (Comfeel®Plus; Coloplast) is used for this purpose.

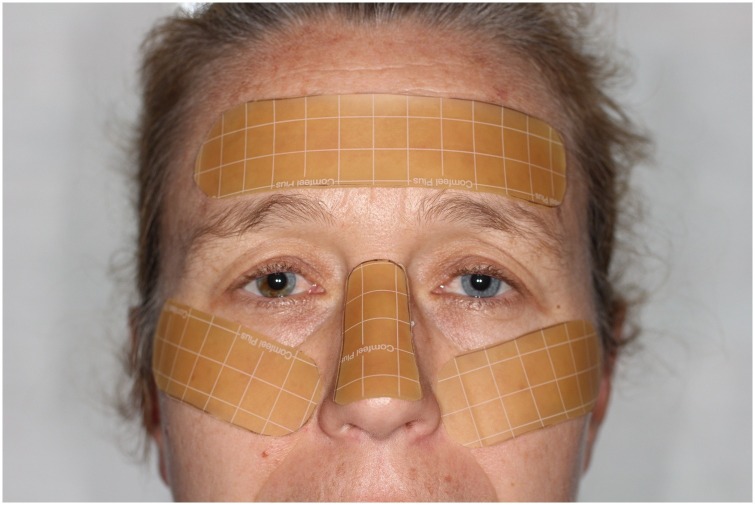

After the hydrocolloid dressing has been trimmed the adhesive dressing is then placed over the skin of the nasal dorsum, cheeks and forehead, covering the area where the mask and protective glasses will rest (Fig. 2, Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 2.

This nurse has hydrocolloid on her cheeks as well as her forehead to stop her protective outfit from rubbing and causing pain.

Fig. 3.

The protective equipment adapts perfectly to the facial surface and the skin on which both the mask and glasses rest. It is completely protected.

A particularly damaged and painful location despite daily use of the strips of for the masks and the elastic band straps of protective glasses and screens with cranial support are the areas of the root of the auricular helix. We will also apply a hydrocolloid dressing to measure friction in these areas (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

The areas of the root of the auricular helix must especially be covered by the hydrocolloid to avoid skin injury.

Most publications related to the prevention of facial injuries caused by medical equipment are described in patients but not amongst healthcare professionals.1, 2, 3 The medical devices that most often cause skin lesions at facial level are ventilation masks, nasogastric tubes, and orotracheal tubes alongside their securing tapes.

The use of face masks and goggles for hours on end in this COVID-19 pandemic situation results in greater sweating which is aggravated by the large number of patients being treated and the stressful situation of possible contagion.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was first officially reported in Asia in February 2003.4 Personal protective equipment such as the N95 mask, gloves, and gowns would be worn often for hours at a time. The most common adverse reaction reported to the N95 mask was acne; some healthcare professionals suffered from the pressure-related effects of mask use, mainly in the form of a rash or sores over the nasal bridge. Previous studies have shown the incidence of nasal bridge pressure ulcers during the use of acute Non-invasive ventilation to be between 5%–20%.5

Conclusion

We recommend the use of hydrocolloid sheets cut to the size and shape of each health professional to avoid continuous chafing in the areas surrounding the mask and protective glasses at the level of the nasal dorsum, forehead and cheeks during the COVID-19 crisis.

Ethics statement/confirmation of patients’ permission

Ethics approval is not required. Patients’ permission not applicable

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

J.L. Del Castillo Pardo de Vera, Email: jldelcastillopardo@gmail.com.

S. Reina Alcalde, Email: kony74@hotmail.com.

J.L. Cebrian Carretero, Email: rodrigator2001@hotmail.com.

M. Burgueño García, Email: mburgueno@me.com.

References

- 1.Schwartz D., Magen Y.K., Levy A. Effects of humidity on skin friction against medical textiles as related to prevention of pressure injuries. Int Wound J. 2018:1–9. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schallom M., Cracchiolo L., Falker A. Pressure ulcer incidence in patients wearing nasal-oral versus fullface noninvasive ventilation masks. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24:349–356. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lew T.W.K., Kwek T.K., Tai D. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill patients with SARS. JAMA. 2003;290:374–380. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foo C.C., Goon A.T., Leow Y.H. Adverse skin reactions to personal protective equipment against acute respiratory syndrome—a descriptive study in Singapore. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:291–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamaguti W.P., Moderno E.V., Yamashita S.Y. Treatment-related risk factors for development of skin breakdown in subjects with acute respiratory failure undergoing non-invasive ventilation or CPAP. Respir Care. 2014;59:1530–1536. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]