To the Editor:

Recent evidence derived from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), shows a direct correlation between the severity of systemic inflammation, progression to respiratory failure, and fatal outcome.1 The appearance of clinical signs of severe pneumonia is associated with progressive and persistent elevation of D-dimer and inflammatory markers, including ferritin, a laboratory biomarker of macrophage activation.1 These findings are consistent with the characteristics of the immunopathological infiltrate described in lungs infected with SARS-CoV-2, which is marked by diffuse macrophage infiltration and is consistent with cytokine overproduction.2 , 3 These features are reminiscent of syndromes characterized by overt inflammation driven by the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as macrophage activation syndrome and Still’s disease, which suggests that an early anti-inflammatory approach in patients who develop interstitial pneumonia could be crucial to prevent the progression of lung damage toward respiratory failure requiring ventilatory support and ultimately death.4

The IL-6 blocker tocilizumab, administered with the same protocol used in cytokine release syndrome secondary to chimeric antigen receptor-T therapies, has provided encouraging preliminary results.5 These results support the use of anti-inflammatory treatments in the management of COVID-19–related pneumonia. The potential effectiveness of glucocorticoid therapy, although controversial, has been recently highlighted in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome.6 The rapid expansion of the pandemic in Italy in the past weeks has led to a shortage of tocilizumab, thus prompting the search for alternative therapeutic strategies based on other cytokine blockers. Recent studies have shown that coronavirus regulates the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome by inducing the maturation and secretion of IL-1β,7 suggesting a potential role for IL-1 inhibitors in the management of the inflammatory complications induced by SARS-CoV-2.

Here, we report the first experience with the early use of high intravenous (IV) doses of the recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) in 5 patients with severe/moderate COVID-19 with pulmonary involvement. The rationale for the use of anakinra at high IV doses, rather than at the standard regimen of 100 mg/daily subcutaneously, derives from previous experiences in other conditions characterized by massive cytokine release, such as severe secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis8 and sepsis.

On admission, all patients displayed a recent onset of dyspnea, associated with fever, systemic inflammation, rapidly worsening respiratory distress, and marked lung abnormalities on chest computed tomography (Table I ; Fig 1, A-C). Soon after admission, all patients received, after providing informed consent, treatment with high-dose IV anakinra added to the current standard of care (Table I). The starting dose was 100 mg every 8 hours (300 mg/daily) for 24 to 48 hours, followed by tapering, according to clinical response. Methylprednisolone was also administered in patient 4 (Table I). The off-label use of anakinra was approved by the internal review board of the Galliera Hospital.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of patients at hospital admission, therapeutic interventions, and outcome

| Characteristic | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 62 | 59 | 40 | 55 | 56 |

| Sex | M | M | F | F | M |

| Comorbidities | Cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia | — | — | Cardiovascular isease, hypertension | — |

| Emergency department presentation | Clinical |

Fever, cough, fatigue, splenomegaly |

Fever, cough, fatigue, dyspnea |

Fever, cough, fatigue, dyspnea, nausea |

Fever, cough, dyspnea |

Fever, fatigue, dyspnea |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) |

Sat. O2 |

37.7 |

96% |

38.2 |

97% |

37.6 |

94% |

37 |

97% |

37.1 |

85% |

|

| PaO2/FiO2 |

Clinical score∗ |

308 |

Moderate |

345 |

Moderate |

226 |

Severe |

116 |

Severe |

213 |

Severe |

|

| SARS-CoV-2 nasal swab | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | |||||||

| Anakinra administration | Days after disease onset | 10 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 7 | ||||||

| Days after admission | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Cumulative dose (mg) | 600 | 1400 | 900 | 1000 | 800 | |||||||

| Other therapies administered | HCQ, enoxaparin, antiviral, azythromycin | HCQ, enoxaparin, antiviral, azythromycin | HCQ, enoxaparin, antiviral, azythromycin | MPred (0.5-1 mg/kg/d for 3 d), enoxaparin, azythromycin | HCQ, enoxaparin, antiviral, azythromycin | |||||||

| Results | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days of | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | ||||||

| CPAP (PEEP 10 cm H2O) | FiO2 35%-60% (Venturi mask) | — | 13 | — | 13 | 3 | — | — | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| FiO2 24%-32%(nasal cannula) | Ambient air | — | 3 | — | 1 | 4 | 1 | — | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Hospitalization | Hospitalization after anakinra | 16 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 9 |

| Parameter | Range | Day −1/+1 | Discharge | Day −1/+1 | Discharge | Day −1/+1 | Discharge | Day −1/+1 | Discharge | Day −1/+1 | Discharge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaO2/FiO2 | — | — | 233 | 411 | 135 | 419 | 226 | 322 | 116 | 350 | 157 | 304 |

| CRP | 0-0.5 mg/dL | 5.9 | 0.07 | 5.62 | 1.08 | 16.5 | 1.74 | 3.8 | 0.16 | 12.18 | 0.85 | |

| Ferritin | 30-400 ng/mL | 2,760 | 826 | 2,948 | 1,147 | 1,346 | 1,130 | 460 | 294 | 1,637 | 1,292 | |

| D-dimer | 0-500 ng/mL | 43,033 | 624 | 376 | 622 | 665 | 466 | 3,587 | 1,050 | 684 | 673 | |

| LDH | 135-200 U/L | 443 | 203 | 392 | 242 | 322 | 263 | 493 | 226 | 296 | 198 | |

| Lymphocytes | 1.13-3.37 109/L | 0.88 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 1.56 | 0.95 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.07 | 0.7 | 1.51 | |

| Neutrophils | 2.01-5.72 109/L | 7.09 | 4.22 | 4 | 2.9 | 5.22 | 3.83 | 3.7 | 2.88 | 16.46 | 4.4 | |

| Platelets | 0-0.5 mg/dL | 155 | 332 | 300 | 537 | 167 | 230 | 241 | 194 | 289 | 400 | |

CPAP, Continuous positive airway pressure; CRP, C-reactive protein; F, female; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; M, male; MPred, methylprednisolone; PaO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

Antiviral: ritonavir and darunavir for 1 wk.

Clinical score according to “Diagnosis and treatment protocol for novel coronavirus pneumonia” (https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/pdf/2020/1.Clinical.Protocols.for.the.Diagnosis.and.Treatment.of.COVID-19.V7.pdf).

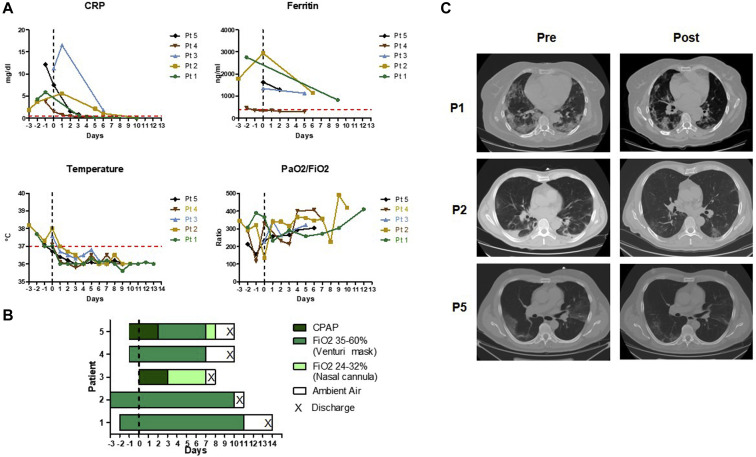

Fig 1.

A, Course of inflammatory biomarkers, body temperature, and lung function parameters over time. The vertical line (time 0) denotes the day of anakinra start, and the horizontal line in red denotes the upper limit of normal values. B, Course of oxygen support before and after anakinra treatment. C, CT scans on admission showing ground glass opacities and infiltration in lungs in P1 and P5 and multiple small patchy shadows and interstitial changes in P2 (left) and course after treatment, before discharge (right). CPAP, Continuous positive airway pressure; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; PaO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen.

All 5 patients experienced rapid resolution of systemic inflammation, and remarkable improvement in respiratory parameters, with reduction of oxygen support requirement and early amelioration of chest computed tomography scan abnormalities before discharge in 3 patients (Table I; Fig 1, A-C). All patients were discharged 6 to 13 days after the start of anakinra. No secondary infections or other adverse events were observed.

These results compare favorably with literature data, showing that patients with a similar inflammatory phenotype and severe respiratory impairment have a high risk for a lethal outcome.1 Our decision to use anakinra was motivated by the shortage of tocilizumab and by the high mortality rate previously observed in our center among patients with prominent inflammatory features and marked respiratory distress. In our preliminary experience, the addition of high-dose IV anakinra to the standard of care enabled rapid control of the inflammatory manifestations and led to a favorable outcome.

We acknowledge the limitations related to the noncontrolled nature of our study, the small size of the patient population, the short-term duration of the treatment, and the variability in laboratory biomarkers. However, these preliminary findings suggest the potential safety of an early anti-inflammatory treatment with high doses of IV anakinra, in the cytokine release syndrome occurring in patients with COVID-19. We propose, therefore, to add anakinra to the list of possible anticytokine treatments for COVID-19–related pneumonia.6 The ultimate assessment of the efficacy and safety of anakinra therapy in COVID-19 pneumonia should be conducted in the context of randomized clinical trials. In this line, an open-label trial based on the administration of 400 mg daily of IV anakinra for 14 days has just started patient recruitment in Italy (NCT04324021) and will provide further evidence. In our preliminary experience, even lower doses of IV anakinra and shorter treatment duration provided a favorable outcome, without significant side effects, in particular secondary infections.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: R. Caorsi receives speaker’s fees and has consultancies for Novartis and SOBI. A. Ravelli receives speaker’s fees and has consultancies for Novartis and SOBI. M. Gattorno receives speaker’s fees and has consultancies for Novartis and SOBI. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Gao Y, Qiao L, Wang W, Chen D. Inflammatory response cells during acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [published online ahead of print April 13, 2020]. Ann Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.7326/L20-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Metha P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunesuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson LA, Canna SW, Schulert GS, Volpi S, Lee PY, Kernan KF, et al. On the alert for cytokine storm: immunopathology in COVID-19 [published online ahead of print April 15, 2020]. Arthritis Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review [published online ahead of print April 13, 2020]. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention [published online ahead of print February 24, 2020]. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Shakoory B., Carcillo J.A., Chatham W.W., Amdur R.L., Zhao H., Dinarello C.A. Interleukin-1 receptor blockade is associated with reduced mortality in sepsis patients with features of macrophage activation syndrome: reanalysis of a prior phase III trial. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:275–278. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eloseily E.M., Weiser P., Crayne C.B., Haines H., Mannion M.L., Stoll M.L. Benefit of anakinra in treating pediatric secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:326–334. doi: 10.1002/art.41103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]