Abstract

Due to the wide availability, rapid execution, low cost, and possibility of being acquired at the patient's bed, chest X-Ray is a fundamental tool in the diagnosis, follow-up and evaluation of the treatment effectiveness of patients with pneumonia, also in the context of COVID-19 infection. However, false negative cases are possible.

We report 4 cases of false negative chest X-Rays, in patients who were diagnosed positive for COVID-19 by real-time transverse-transcript-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and executed chest unenhanced CTs just after the X-Rays, demonstrating signs of COVID-19 pneumonia.

Keywords: Pneumonia, Viral, Multidetector computed tomography, COVID-19, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Radiography

Introduction

As a consequence of the rapid increase of patients who are positive or suspected positive for COVID-19, a high number of chest imaging examinations are required. Thanks to the wide availability, rapid execution, low cost, and possibility of being acquired at the patient's bed, chest X-Ray has become an essential tool in the diagnosis, follow-up, and evaluation of the treatment effectiveness of COVID-19 pneumonia.1 However, due to the intrinsic limitations of this technique, false-negative cases are possible.

We aim to report four cases of false-negative chest x-rays, in patients who were diagnosed positive for COVID-19 by real-time transverse-transcript-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and executed chest unenhanced CT scans just after the X-Rays, demonstrating signs of COVID-19 pneumonia.

Material and methods

All patients were considered normal weight, so the examinations were performed with standard protocols. Chest X-Rays were acquired with the same fixed digital X-Ray unit (DigitalDiagnost C90, Philips) in both posteroanterior and lateral projection, in the orthostatic position. Source to image distance was set at 180 cm for all of the exposures. Acquisition parameters were: 98 kV, 7 mAs, for the posteroanterior projection and 110 kV and 8 mAs for the lateral projection.

Chest CT scans were executed on the same CT scanner (Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens), with the following acquisition parameters: reference kV, 120; reference mAs, 150 (with automated tube current modulation, CareDose); rotation time, 0.5 s; collimation, 128 × 0.6 mm; pitch value, 1; scan direction, craniocaudal, and reconstructed as follows: for lung, slice thickness of 0.75 mm with reconstruction spacing of 0.5 mm, for mediastinum, slice thickness of 3 mm with reconstruction spacing of 1 mm.

All the X-Ray and CT examinations have been evaluated and formally reported by experienced chest radiologists. CTs were performed the same day as the X-Ray, after a median time interval of 60 ± 20 min.

Case 1

A thirty-seven-year-old male colleague, with no previous significant medical history, presented to our Emergency Department with cough and fever up to 39° for 2 days. His vital signs were within the normal ranges. Ear temperature was 38.5 °C and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. Blood tests showed normal results (included C Reactive Protein that was 4.4 mg/L). Chest X-Ray, executed in posteroanterior and lateral projections, on fixed X-Ray equipment (Fig. 1 A and B), was reported by an experienced radiologist as negative.

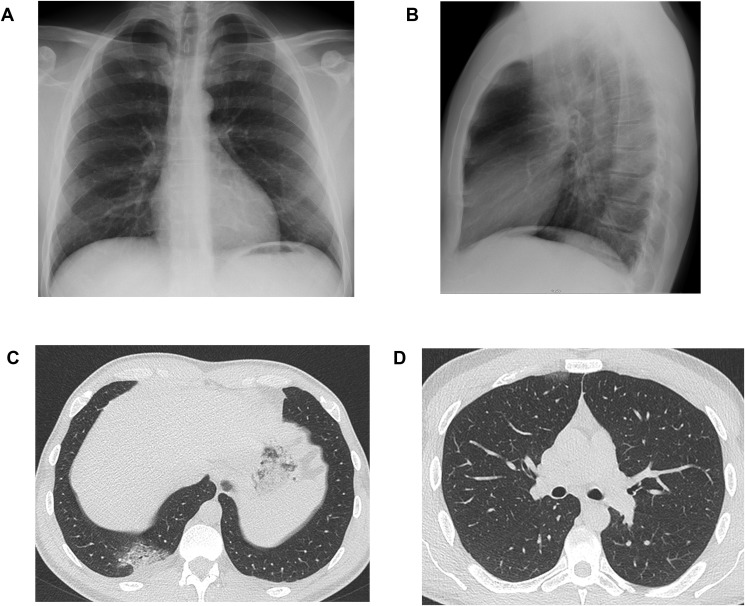

Figure 1.

Posteroanterior (Fig. 1A) and lateral (Fig. 1B) projections of the chest X-Ray of a thirty-seven-year-old male colleague, who presented to our Emergency Department with cough and fever up to 39° for 2 days. Chest X-Ray did not demonstrate any lung abnormalities. Chest CT executed just after the X-Ray, showed the presence of a crazy paving area in the right posterior costophrenic recess with mild pleural effusion (Fig. 1C). A small subpleural area of GGO is located anteriorly in the upper right lobe (Fig. 1D).

Due to possible exposure to a positive COVID-19 patient, while pending the results of the throat swab, a chest computed tomography (CT) was performed. CT demonstrated the presence of an area of crazy-paving pattern in the right posterior costodiaphragmatic recess, and a focal ground glass opacity (GGO) in the superior right lobe, anteriorly (Fig. 1C and D). The patient was admitted to a dedicated ward.

Case 2

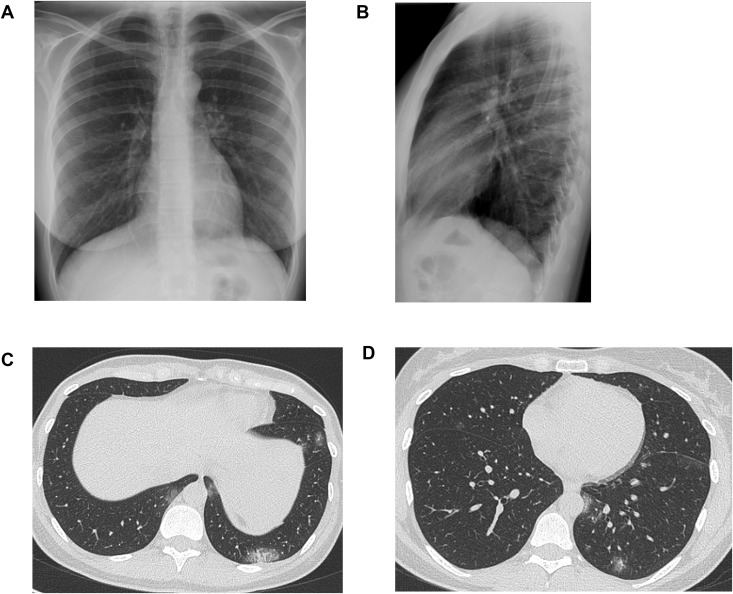

A thirty-seven-year-old female colleague, without significant clinical history, presented with cough and fever up to 38° for 4 days. Her vital signs were within the normal ranges. Ear temperature was 38 °C and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. Blood tests showed normal results, except for serum lactate level (189 U/L). Chest X-Ray was negative (Fig. 2 A and B). Due to the high clinical suspicion of COVID-19 infection, unenhanced chest CT was performed, showing an area of crazy paving in the left posterior costodiaphragmatic recess (Fig. 2B) and patchy GGOs (Fig. 2C and D). The patient was admitted to a dedicated ward.

Figure 2.

Posteroanterior (Fig. 2A) and lateral (Fig. 2B) projections of the chest X-Ray of a thirty-seven-year-old female colleague, who presented with cough and fever. Chest X-Ray did not demonstrate any lung abnormalities. Chest CT executed just after the X-Ray, showed an area of crazy paving in the left posterior costophrenic recess (Fig. 2B); patchy GGOs are also bilaterally recognizable (Fig. 2B and C).

Case 3

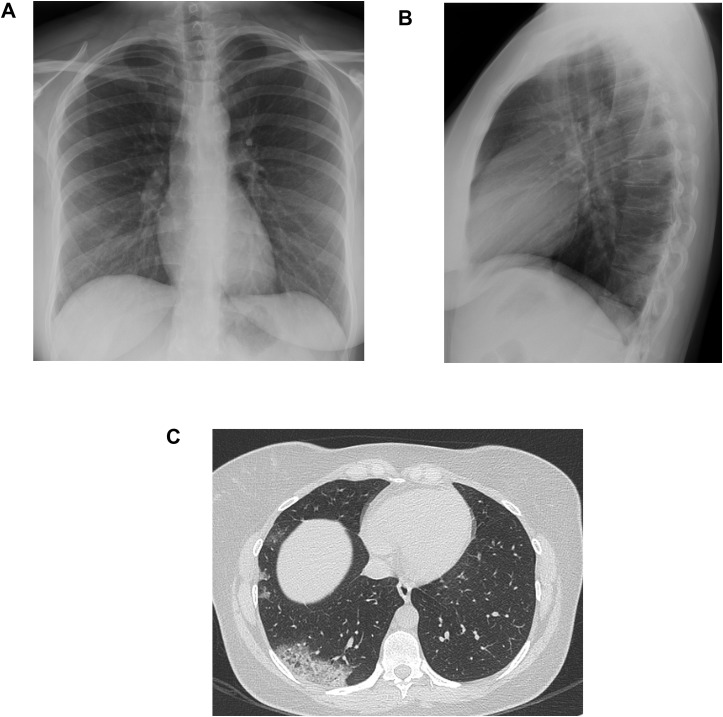

A thirty-three-year-old nurse, without significant clinical history, presented with cough and fever up to 38° for 4 days. Her vital signs were within the normal ranges. Ear temperature was 37.5 °C and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. Blood tests showed normal results, except for serum lactate level (197 U/L) and mildly increased C Reactive Protein (12.5 mg/L). Chest X-Ray was negative (Fig. 3 A, B). Due to the high clinical suspicion of COVID-19 infection, chest CT was performed the same day, demonstrating an extensive consolidation in the right lower lobe, and some patchy GGOs with lateral peripheral distribution (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Posteroanterior (Fig. 3A) and lateral (Fig. 3B) projections of the chest X-Ray of a thirty-three-year-old nurse, who presented with cough and fever. Chest X-Ray was reported as negative; at a review, a slight thickening of the bronchovascular bundles could be observed at the lower right field. Chest CT executed just after the X-Ray, showed an extensive consolidation, with a peripheral posterior location in the right lower lobe, and some patchy GGOs with lateral peripheral distribution (Fig. 3C).

Case 4

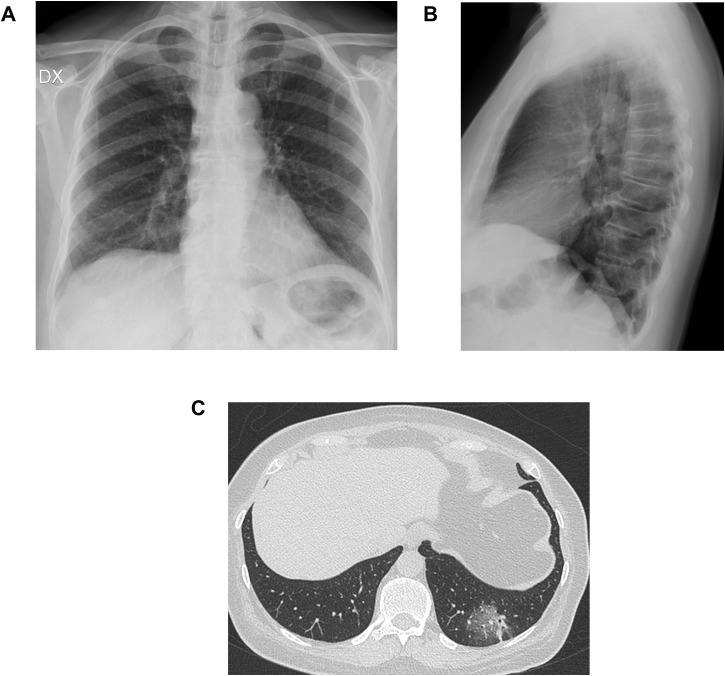

A fifty-six-year-old woman, without significant clinical history, who initially presented to our Emergency Department with chest pain, cough, dyspnoea, and fever up to 38.5° for 4 days. Her vital signs were within the normal ranges. Ear temperature was 38 °C and oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Blood tests showed normal results, except for serum lactate level (189 U/L) and mildly increased C Reactive Protein (9.6 mg/L). The chest X-ray was negative (Fig. 4 A, B). Chest CT demonstrated a posteriorly located GGO in the lower left lobe, with superimposed interlobular septal thickening, resulting in a crazy paving pattern (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Posteroanterior (Fig. 4A) and lateral (Fig. 4B) projections of the chest X-Ray of a fifty-six-year-old woman, who presented with chest pain, cough, dyspnoea, and fever. Chest CT demonstrated an area of crazy paving pattern, posteriorly located in the lower left lobe (Fig. 4C).

Discussion

Even though chest X-Ray represents the faster and widely available tool for lung parenchyma assessment, the COVID-19 imaging literature is currently focused on chest CT, due to the higher sensitivity.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Some authors proposed the chest CT as the first assessment technique for COVID-19 infection in epidemic areas,8 , 9 and this scenario implies a huge burden on Radiology Departments, as well as the designation of CT machines dedicated for the examinations of suspected and positive COVID-19 patients only, with the application of severe infection control procedures.10

The American College of Radiology (ACR) does not recommend the use of chest CT to screen patients for COVID-19 pneumonia and stated that CT scanning should be reserved for symptomatic patients with specific clinical indications.11

ACR also advises to deploy portable radiography machines in the Departments dedicated to the acceptance and treatment of suspected or positive COVID-19 patients, to perform chest X-Rays when a lung evaluation is medically needed while avoiding moving patients.11

Therefore, we can consider chest X-Ray as a first-line tool to assess the presence of lung abnormalities in symptomatic patients, suspected for COVID-19 infection. In our Emergency Department, screening imaging examinations were not performed, we executed chest X-Rays only in patients with suspected symptoms.

The article by Wong et al. retrospectively analysed 64 patients, who received chest X-rays at baseline and follow-up, for a total of 255 examinations.1 They observed that consolidation was the most common finding, observed in 47% of cases, followed by GGO, as previously observed for CT.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Chest abnormalities were mainly bilateral and peripheral, with a prevalent involvement of the lower zones, and a peek at 10–12 days from the onset of the symptoms.

Wong et al. also proposed a radiograph score for a quantification of the consolidation and GGO according to their extension: 0 = no involvement; 1= <25%; 2 = 25–50%; 3 = 50–75%; 4= >75% involvement. In their case series, they reported a sensitivity of 69% of the baseline chest X-Ray, and the presence of one patient with falsely negative chest X-Ray, when compared to CT.1

To the best of our knowledge, no other study analysed the usefulness and the performance of chest X-Ray in the study of COVID-19 patients.

Our institution does not routinely perform chest CT for all COVID-19 patients; in our consecutive case series of 100 X-Rays of positive COVID-19 patients (mean age: 64 ± 16 years; 70 males, 30 females), confirmed by RT-PCR, 25/100 (25%) also received chest CT. Four chest CT out of 25 (16%) were performed after a negative X-Ray.

3/4 (75%) patients showed areas of crazy paving pattern at CT; 3/4 (75%) showed patchy GGOs; 1/4 (25%) showed a consolidation. In patients affected by COVID-19 pneumonia, pure GGOs and GGOs with reticular or interlobular septal thickening (resulting in the crazy paving pattern) seem to be the most common findings, whereas pure consolidation is less common.9 Our CT findings are in line with those previously reported in other CT studies on COVID-19 patients.4 , 6 , 9 , 12 , 13 3/4 (75%) showed a unilateral distribution of the lesions; 4/4 (100%), a peripheral distribution of lung abnormalities; 4/4 (100%), a location in the posterior part; 4/4 (100%) showed lower zones involvement. The peripheral distribution, the involvement of posterior and lower lung zones are considered typical CT features of COVID-19 pneumonia; even if bilateral affection is more frequent, unilateral pneumonia has also been reported1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , 9 , 12, 13, 14, 15

Due to the high rate of GGOs, findings can be missed on X-Rays,14 but also confirmed positive patients can show negative chest CT.15

In our case series, 3/4 patients (75%) were healthcare workers, therefore considered high-risk subjects. A previous study observed that nearly 4% of the confirmed COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China, were in healthcare workers,16 suggesting the hospitals as a potential location of transmission even among workers who are trained to protect themselves from potential contagions.17

In conclusion, in positive COVID-19 patients, chest X-Rays could be falsely negative. The presence of suspected symptoms in epidemic areas should alert the Clinicians to this possibility.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Acknowledgement

No funding has been received.

References

- 1.Wong H.Y.F., Lam H.Y.S., Fong A.H., Leung S.T., Chin T.W., Lo C.S.Y. Frequency and distribution of chest radiographic findings in COVID-19 positive patients. Radiology. 2019;27:201160. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou S., Wang Y., Zhu T., Xia L. CT features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia in 62 patients in Wuhan, China. Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng M.-Y., Lee E.Y.P., Yang J., Li X., Wang H., Mei-Sze M. Imaging profile of the COVID-19 infection: radiologic findings and literature review. Radiol Cardiothorac Imag. 2020;2(1) doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung M., Bernheim A., Mei X., Zhang N., Zeng X., Cui J. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ai T., Yang Z., Hou H., Zhan C., Chen C., Lv W. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan F., Ye T., Sun P., Gui S., Liang B., Li L. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernheim A., Mei X., Huang M., Yang Y., Fayad Z.A., Zhang N. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chinese Society of Radiology Radiological diagnosis of new coronavirus infected pneumonitis: expert recommendation from the Chinese Society of Radiology (First edition) Chin J Radiol. 2020;54:E001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zu Z.Y., Jiang M.D., Xu P.P., Chen W., Ni Q.Q., Lu G.M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a perspective from China. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orsi M.A., Oliva A.G., Cellina M. Radiology department preparedness for COVID-19: facing an unexpected outbreak of the disease. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACR recommendations for the use of chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) for suspected COVID-19 infection | American College of Radiology. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection

- 12.Wu J., Wu X., Zeng W., Guo D., Fang Z., Chen L. Chest CT findings in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and its relationship with clinical features. Invest Radiol. 2020;55(5):257–261. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon S.H., Lee K.H., Kim J.Y., Lee Y.K., Ko H., Kim K.H. Chest radiographic and CT findings of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): analysis of nine patients treated in Korea. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21(4):494–500. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong W., Agarwal P.P. Chest imaging appearance of COVID-19 infection. Radiol Cardiothorac Imag. 2020 doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lei J., Li J., Li X., Qi X. CT imaging of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295(1):18. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 Feb 24 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker M.G., Peckham T.K., Seixas N.S. Estimating the burden of United States workers exposed to infection or disease: a key factor in containing risk of COVID-19 infection. PloS One. 2020 Apr 28;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]