Abstract

Morton’s neuroma is a common pathology affecting the forefoot. It is not a true neuroma but is fibrosis of the nerve. This is caused secondary to pressure or repetitive irritation leading to thickness of the digital nerve, located in the third or second intermetatarsal space. The treatment options are: orthotics, steroid injections and surgical excision usually performed through dorsal approach. Careful clinical examination, patient selection, pre-operative counselling and surgical technique are the key to success in the management of this condition.

Keywords: Morton’s neuroma foot forefoot pain digital nerve

1. Introduction

Morton’s neuroma was first described in the literature in 1876 by an American surgeon, Thomas George Morton. It is a common pathology affecting the forefoot. It is not a true neuroma but is fibrosis of the digital nerve. This is caused secondary to pressure or repetitive irritation leading to thickness of the nerve, located in the second or third intermetatarsal space. The third intermetatarsal space is most commonly affected. Histologically the neuroma has neural oedema, demyelination (axonal injury) and perineural fibrosis.1, 2, 3, 4 This degenerate tissue therefore causes localised pain and discomfort mainly on weight bearing. Current literature suggests that the use of pointed heeled shoes may be a causative factor because this increase in pressure over the forefoot can lead to neuronal injury.1

2. Presentation

The classical description of a Morton’s neuroma is paraesthesia within the affected digital nerve, accompanied by forefoot pain and is more commonly seen in females. 17% of patients describe some trauma to the foot resulting in symptoms.5 The most common characteristic of the pain is burning in nature. Altered sensations and feeling a “pebble in the shoe” is reported by more than 50% of patients. The pain is often exacerbated by walking, use of tight or heeled shoes and is reported by runners due to the increased weight bearing through the forefoot.5,6 Resting the foot or removing the shoe improves pain in most cases especially early in the onset of this condition. In chronic cases the pain could be constant. Night pain and rest pain is reported by about 25% of patients.5

3. Examination

Clinically, there are no visual cues to the presence of a neuroma. Any deformity of the foot specially hallux valgus can lead to overcrowding of the toes and increased pressure on the lesser toes, and is therefore an important predisposing factor. Plantar callosities around metatarsal heads are suggestive of transfer metatarsalgia, synovitis, subluxation or dislocation of metatarso-phalangeal joint of 2nd or 3rd toes. The other differential diagnoses include: plantar plate tear, Freiberg’s disease, stress response or stress fracture of metatarsals. It has been reported that clinical assessment by experienced clinician has up to 98% accuracy as compared to an ultrasound (USS) examination.5

The most sensitive clinical tests for the diagnosis of Morton’s neuroma are the thumb index finger squeeze test, Mulder’s click test and foot squeeze test in that order. Thumb index finger test is performed by applying pressure in the intermetatarsal space. Thumb is placed on the dorsal aspect whereas index finger is kept on the plantar aspect. Positive test results in pain in presence of Morton’s neuroma. It is important to make sure that the pressure is exerted in the intermetatarsal space and not in the metatarsophalangeal joint itself. Splaying of toes is a good indication that the test has been performed appropriately.

Mulder’s click test is performed by dorsiflexing the foot and squeezing the metatarsals. An audible click is suggestive of presence of Morton’s neuroma. This test does not specify which intermetatarsal space which is affected. It is dependent on size of the neuroma and is usually positive in Morton’s neuroma measuring 1 cm or more.5

4. Role of imaging

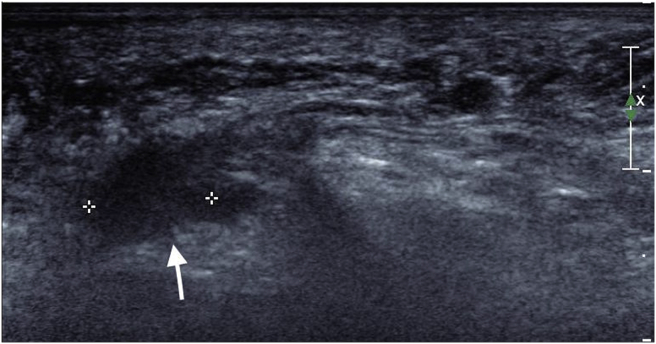

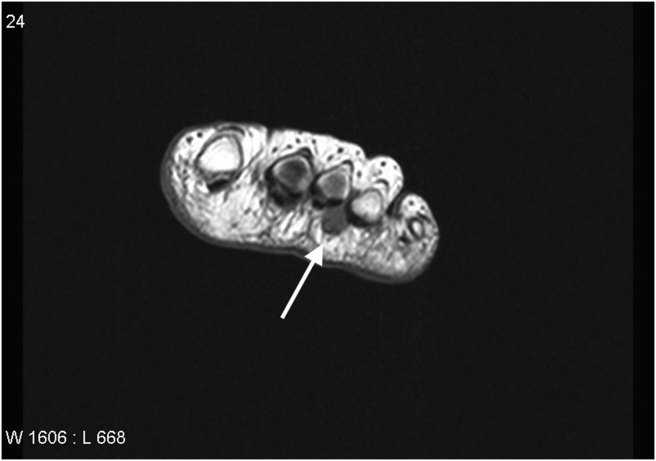

A baseline weight bearing radiograph will aid in the exclusion of other causes of forefoot pain and give an overview of the osteology. USS and Magnetic Resonance imaging (MRI) are comparable modalities for diagnosing Morton’s neuroma.2,7,8 An experienced musculoskeletal radiologist can elicit a neuroma with a sensitivity of 95% with USS (Fig. 1). However, if there is any doubt of the diagnosis, an MRI scan is the gold standard investigation to identify a neuroma, which can most easily be seen on T1 axial slice (Fig. 2).8,9

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound scan showing Morton’s Neuroma (bold arrow).

Fig. 2.

MRI scan showing Morton’s Neuroma (bold arrow).

5. Size

The presence of a neuroma will not automatically cause the patient to experience the symptoms of a Morton’s neuroma. Bencardino reviewed 57 patients and noted that a third of the patients radiologically had a neuroma but were asymptomatic. The mean diameter was 4.1 mm in the asymptomatic group compared to 5.3 mm in the symptomatic group.10 The diagnosis of Morton’s neuroma is relevant only when the transverse diameter on an MRI scan is 5 mm or more and can be correlated to clinical findings.11 Sharp et el reviewed 29 cases and found no correlation between size and severity of symptoms.8 A prospective randomised controlled trial demonstrated no statistically significant difference in the mean size of neuromas that responded to treatment with steroid injections (11 mm), compared to those that did not (12.5 mm). Authors of the study also noted that the size of the neuroma was not significantly different in patients who had a recurrence of symptoms as compared to those who continued to be pain free at 12 months.12 Makki noted that the effect of steroid injection was sustained if the lesion was smaller than 5 mm.13 The literature therefore suggests that size of the lesion does not always correlate with symptom severity, and although smaller neuromas will respond to steroid injections better than larger ones, patient reported outcome will improve for both with the injections.

6. Management

The management of neuroma can be split into non-operative measures or surgical management. The treatment algorithm, generally involves non-operative measures including injection therapy and if these methods fail to improve symptoms, surgical excision is the next option.14

Patient education is very important and the use of wide toebox shoes can be the simplest method of managing symptoms. However, patient compliance is an issue and can result in failure to resolve symptoms.

7. Orthotics

The commonest form of treatment (initially) is the Metatarsal Bar. This insole, made by orthotists spreads the heads of the metatarsals to relieve pressure on the neuroma and thus improve symptoms. However, this does require the patient to wear broad toe box shoes and use the inserts so a degree of compliance is required. There is no evidence to support the use of inversion or eversion insoles, with studies demonstrating no significant improvement in patient reported outcomes.15,16 Their use is therefore not recommended for the treatment of Morton’s Neuroma.

8. Injection therapy

The use of therapeutic injections is very common in the management of Morton’s neuroma, and multiple therapies have been used. The injection can be guided by USS or done using a landmark technique. A randomised trial by Mahadevan et al did not show any statistical difference in patient outcomes after a steroid injection using USS or without.12 Santiago et al. noted that short term improvement in visual analogue scale (VAS) over 3 months in the group of patients having USS guided injections was better but the effect was not sustained at 6 months.17 In a randomised controlled study comparing insoles with steroid injections, Saygi et al. reported that orthotics on their own were not very helpful. Their results suggested that 82% of patients who received 2–3 steroid injections reported complete satisfaction at 12 months.18

Corticosteroid is currently the mainstay of injection treatment for Morton’s Neuroma. Outcomes for this modality show an improvement in multiple different patient reported outcome measures at 12 months.12,13,18, 19, 20 Although the mechanism of action is unclear as the neuroma is degenerate in nature, the understanding is that the steroid reduces the inflammation surrounding the neuroma and therefore reduces pain and also local pressure effects. In a randomised controlled trial, it has been shown that corticosteroid injections are more effective than local anaesthetic alone.20 At 1 year following steroid injection, a third of patients require surgical excision due to recurrence of pain.12,13,19 It has been shown that steroid injections are more effective if used within one year of onset of symptoms.19

There are a number of studies looking into the use of ethanol/alcohol injections into neuroma, which show improvement in patient reported outcome measures at 12 months and reduction in neuroma size.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 This included one study at 5 years by Gurdezi, which followed up on the previous study by Hughes et al.22,27 Although the 12 month outcomes were promising with 84% patients reporting complete resolution of symptoms, at 5 years this was the case in only 29% of patients. In addition, a third of patients reported complications which include burning pain associated with alcohol injections which in some cases lasted for weeks.22 Moreover, subsequent surgery following alcohol injections can be difficult due to increased fibrosis and for these reasons we do not recommend alcohol injections for the treatment of Morton’s neuroma.

Radiofrequency ablation is another treatment option which involves inserting a probe into the neuroma. The probe is then heated to between 85 and 90 °C. Although multiple studies report good patient reported outcomes, they have all been small, retrospective in design, with short term follow up. Radiofrequency ablation is not recommended as routine treatment by National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE).28, 29, 30

Similarly, capsaicin, cryotherapy, Yttrium Aluminium Garnet (YAG) laser, extra-corporeal shockwave therapy and Botox injections have all been studied for the treatment of Morton’s neuroma. However, all were small studies with short term follow up, and only weak evidence for their use and are therefore not recommended by the authors.31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37

9. Surgical excision

The neuroma can be excised by two methods, either a dorsal or plantar approach. The dorsal approach allows the patient to weight bear immediately, with the plantar approach there is a risk of wound complications and scar sensitivity. However, no studies have proven benefit over one or the other.15

The plantar approach is less commonly used and success following removal has a broad range from 51% to 85%.38, 39, 40, 41 Wolfort et al. performed a prospective study on 17 neuroma through a plantar approach and achieved an 80% success with return to pre-surgical footwear.38

The dorsal approach, allows immediate weight bearing post-surgery and is better tolerated by patients. Coughlin et al. performed a review of dorsal surgical excision at 5.8 years in 82 patients, of which 85% reported excellent or good outcomes, with 65% remaining pain free at 5.8 years.42 Womack had a 61% success in 232 patients. Dorsal approach is the authors preferred surgical technique (Fig. 3).15,42, 43, 44, 45

Fig. 3.

Dorsal approach for Morton’s Neuroma excision. Bold arrow shows Morton’s Neuroma.

10. Adjacent neuroma

Morton’s neuroma in adjacent intermetatarsal spaces is common with reported incidence as high as 28%.5,46 Multiple studies have reported lower patient satisfaction with excision of adjacent interdigital space neuromas, although the reasoning behind this is uncertain.42,47 There is no clear consensus on whether both neuroma should be excised. Excision of both neuromas can lead to increased complications related to wound healing and numbness. Some clinicians therefore resort to treating this by excising one of the neuromas and decompressing the adjacent intermetatarsal space. Others believe in sequential excision if required following excision of the more symptomatic neuroma.

11. Failure following Morton’s neuroma surgery

The failure rate following surgical excision has been reported as up to 30%. The main reasons for pain following surgical excision are: incorrect diagnosis, neuroma in adjacent intermetatarsal space, incomplete resection, complex regional pain syndrome or recurrence of the Morton’s neuroma also known as stump neuroma. Factors contributing to recurrence include formation of a new neuroma, adhesions and accessory branches of the digital nerves.43,48 There are a number of documented ways of preventing stump neuroma formation.49, 50, 51 Use of steroid injection is the most commonly used modality for dealing with pain following surgical excision. The mechanism of action is breakdown of scar tissue and adhesions. Dellon and Mackinnon described a technique of implantation of the nerve stump within the muscle. In 60 patients with 78 neuromas, 82% of their cohort had a good to excellent results.52 Resection of the neuroma proximally with muscle implantation of the new stump can also be used. Overall the chances of success following revision surgery are much less satisfactory than primary excision.

12. Take home message

Morton’s neuroma is a common cause of forefoot pain. Most cases can initially be managed non surgically. Steroid injections are useful diagnostic and therapeutic non surgical treatment modality. Careful clinical examination, patient selection, pre-operative counselling and surgical technique are the key to success in the management of this condition.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

References

- 1.Wu K.K. Morton’s interdigital neuroma: a clinical review of its etiology, treatment, and results. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1996;35(2):112–119. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(96)80027-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8722878 discussion 187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochman M.G. Imaging of Arthritis and Metabolic Bone Disease. Elsevier Inc.; 2009. Entrapment syndromes; pp. 239–263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morscher E., Ulrich J., Dick W. Morton’s intermetatarsal neuroma: morphology and histological substrate. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21(7):558–562. doi: 10.1177/107110070002100705. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10919620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourke G., Owen J., Machet D. Histological comparison of the third interdigital nerve in patients with Morton’s metatarsalgia and control patients. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64(6):421–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb02243.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7516653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahadevan D., Venkatesan M., Bhatt R., Bhatia M. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for morton’s neuroma compared with ultrasonography. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2015;54(4):549–553. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2014.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganguly A., Warner J., Aniq H. Central metatarsalgia and walking on pebbles: beyond morton neuroma. Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210(4):821–833. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.18460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Symeonidis P.D., Iselin L.D., Simmons N., Fowler S., Dracopoulos G., Stavrou P. Prevalence of interdigital nerve enlargements in an asymptomatic population. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(7):543–547. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharp R.J., Wade C.M., Hennessy M.S., Saxby T.S. The role of MRI and ultrasound imaging in Morton’s neuroma and the effect of size of lesion on symptoms. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(7):999–1005. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b7.12633. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14516035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torres-Claramunt R., Ginés A., Pidemunt G., Puig L., De Zabala S. MRI and ultrasonography in Morton’s neuroma: diagnostic accuracy and correlation. Indian J Orthop. 2012;46(3):321–325. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.96390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bencardino J., Rosenberg Z.S., Beltran J., Liu X., Marty-Delfaut E. Morton’s neuroma. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(3):649–653. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.3.1750649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanetti M., Strehle J.K., Zollinger H., Hodler J. Morton neuroma and fluid in the intermetatarsal bursae on MR images of 70 asymptomatic volunteers. Radiology. 1997;203(2) doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.2.9114115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahadevan D., Attwal M., Bhatt R., Bhatia M. Corticosteroid injection for Morton’s neuroma with or without ultrasound guidance A RANDOMISED CONTROLLED TRIAL. Bone Jt J. 2016;98:498–503. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makki D, Haddad BZ, Mahmood Z, Saleem Shahid M, Pathak S, Garnham I. Efficacy of Corticosteroid Injection Versus Size of Plantar Interdigital Neuroma Level of Evidence: II, Prospective Comparative Study. doi:10.3113/FAI.2012.0722. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Bennett G.L., Graham C.E., Mauldin D.M. Morton’s interdigital neuroma: a comprehensive treatment protocol. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16(12):760–763. doi: 10.1177/107110079501601204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomson C.E., Gibson J.A., Martin D. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004. Interventions for the treatment of Morton’s neuroma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilmartin T.E., Wallace W.A. Effect of pronation and supination orthosis on morton’s neuroma and lower extremity function. Foot Ankle Int. 1994 doi: 10.1177/107110079401500505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santiago F.R., Muñoz P.T., Pryest P., Martínez A.M., Olleta N.P. Role of imaging methods in diagnosis and treatment of Morton’s neuroma. World J Radiol. 2018;10(9):91–99. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v10.i9.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saygi B., Yildirim Y., Saygi E.K., Kara H., Esemenli T. Morton neuroma: comparative results of two conservative methods. Foot Ankle Int. 2005 doi: 10.1177/107110070502600711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markovic M, Bs M. Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection in the treatment of morton’s neuroma. Foot Ankle Int. doi:10.3113/FAI.2008.0483. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Thomson C.E., Beggs I., Martin D.J. Methylprednisolone injections for the treatment of morton neuroma. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2013;95(9):790–798. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fanucci E., Masala S., Fabiano S. Treatment of intermetatarsal Morton’s neuroma with alcohol injection under US guide: 10-month follow-up. Eur Radiol. 2004 doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurdezi S., White T., Ramesh P. Alcohol injection for morton’s neuroma: a five-year follow-up. Foot Ankle Int. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1071100713489555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dockery G.L. The treatment of intermetatarsal neuromas with 4% alcohol sclerosing injections. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1999 doi: 10.1016/S1067-2516(99)80040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musson R.E., Sawhney J.S., Lamb L., Wilkinson A., Obaid H. Ultrasound guided alcohol ablation of morton’s neuroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2012 doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasquali C., Vulcano E., Novario R., Varotto D., Montoli C., Volpe A. Ultrasound-guided alcohol injection for Morton’s neuroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1071100714551386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyer C.F., Mehl L.R., Block A.J., Vancourt R.B. Treatment of recalcitrant intermetatarsal neuroma with 4% sclerosing alcohol injection: a pilot study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2005 doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes R.J., Ali K., Jones H., Kendall S., Connell D.A. Treatment of Morton’s neuroma with alcohol injection under sonographic guidance: follow-up of 101 cases. Am J Roentgenol. 2007 doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chuter G.S.J., Chua Y.P., Connell D.A., Blackney M.C. Ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation in the management of interdigital (Morton’s) neuroma. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(1):107–111. doi: 10.1007/s00256-012-1527-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore J.L., Rosen R., Cohen J., Rosen B. Radiofrequency thermoneurolysis for the treatment of morton’s neuroma. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;51(1):20–22. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Overview | Radiofrequency Ablation for Symptomatic Interdigital (Morton’s) Neuroma | Guidance | NICE.

- 31.Campbell C.M., Diamond E., Schmidt W.K. 2016. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Injected Capsaicin for Pain in Morton’s Neuroma. Pain. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Climent J.M., Mondéjar-Gómez F., Rodríguez-Ruiz C., Díaz-Llopis I., Gómez-Gallego D., Martín-Medina P. Treatment of Morton neuroma with botulinum toxin a: a pilot study. Clin Drug Invest. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gimber L.H., Melville D.M., Bocian D.A., Krupinski E.A., Del Guidice M.P., Taljanovic M.S. Ultrasound evaluation of morton neuroma before and after laser therapy. Am J Roentgenol. 2017 doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seok H., Kim S.-H., Lee S.Y., Park S.W. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy in patients with morton’s neuroma. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2016 doi: 10.7547/14-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fridman R., Cain J.D., Weil L. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy for interdigital neuroma: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2009;99(3):191–193. doi: 10.7547/0980191. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19448168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caporusso E.F., Fallat L.M., Ruth S.M. Cryogenic neuroablation for the treatment of lower extremity neuromas. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2002 doi: 10.1016/S1067-2516(02)80046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomson L., Aujla R.S., Divall P., Bhatia M. Non-surgical treatments for Morton’s neuroma: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Surg. November 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolfort SF, Dellon AL. Treatment of recurrent neuroma of the interdigital nerve by implantation of the proximal nerve into muscle in the arch of the foot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 40(6):404-410. doi:10.1016/s1067-2516(01)80009-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Akermark C., Crone H., Skoog A., Weidenhielm L. A prospective randomized controlled trial of plantar versus dorsal incisions for operative treatment of primary Morton’s neuroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(9):1198–1204. doi: 10.1177/1071100713484300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nery C., Raduan F., Del Buono A., Asaumi I.D., Maffulli N. Plantar approach for excision of a morton neuroma: a long-term follow-up study. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser A. 2012;94(7):654–658. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giannini S., Bacchini P., Ceccarelli F., Vannini F. Interdigital neuroma: clinical examination and histopathologic results in 63 cases treated with excision. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(2):79–84. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coughlin MJ, Saltzman CL, Anderson RB (Robert B. Mann’s Surgery of the Foot and Ankle.

- 43.Mann R.A., Reynolds J.C. Interdigital neuroma - a critical clinical analysis. Foot Ankle. 1983;3(4):238–243. doi: 10.1177/107110078300300411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Womack J.W., Richardson D.R., Murphy G.A., Richardson E.G., Ishikawa S.N. Long-term evaluation of interdigital neuroma treated by surgical excision. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(6):574–577. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2008.0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKEEVER D.C. Surgical approach for neuroma of plantar digital nerve (Morton’s metatarsalgia) J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1952;34-A(2):490. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14917717 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Limarzi G.M., Scherer K.F., Richardson M.L. CT and MR imaging of the postoperative ankle and foot. Radiographics. 2016;36(6):1828–1848. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016160016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kasparek M., Schneider W. Surgical treatment of Morton’s neuroma: clinical results after open excision. Int Orthop. 2013;37(9):1857–1861. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams S.B., Peters P.G., Schon L.C. Persistent or recurrent interdigital neuromas. Foot Ankle Clin. 2011;16(2):317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dellon A.L. Treatment of Morton’s neuroma as a nerve compression. The role for neurolysis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1992;82(8):399–402. doi: 10.7547/87507315-82-8-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poppler L.H., Parikh R.P., Bichanich M.J. Surgical interventions for the treatment of painful neuroma: a comparative meta-analysis. Pain. 2018;159(2):214–223. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mackinnon S.E., Dellon A.L. Results of treatment of recurrent dorsoradial wrist neuromas. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;19(1):54–61. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198707000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dellon A.L., Mackinnon S.E. Treatment of the painful neuroma by neuroma resection and muscle implantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77(3):427–436. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198603000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]