Significance

Police misconduct and use of force have come under increasing scrutiny and public attention. The procedural justice model of policing, which emphasizes transparency, explaining policing actions, and responding to community concerns, has been identified as a strategy for decreasing the number of interactions in which civilians experience disrespectful treatment or the unjustified use of force. This paper evaluates whether a large-scale implementation of procedural justice training in the Chicago Police Department reduced complaints against police and the use of force against civilians. By showing that training reduced complaints and the use of force, this research indicates that officer retraining in procedural justice is a viable strategy for decreasing harmful policing practices and building popular legitimacy.

Keywords: procedural justice, policing, misconduct, complaints, force

Abstract

Existing research shows that distrust of the police is widespread and consequential for public safety. However, there is a shortage of interventions that demonstrably reduce negative police interactions with the communities they serve. A training program in Chicago attempted to encourage 8,480 officers to adopt procedural justice policing strategies. These strategies emphasize respect, neutrality, and transparency in the exercise of authority, while providing opportunities for civilians to explain their side of events. We find that training reduced complaints against the police by 10.0% and reduced the use of force against civilians by 6.4% over 2 y. These findings affirm the feasibility of changing the command and control style of policing which has been associated with popular distrust and the use of force, through a broad training program built around the concept of procedurally just policing.

The August 9, 2014 police shooting of unarmed civilian Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO, gained national prominence by highlighting police use of excessive force. What was unusual about this event was not that it happened, since the level of police shootings has been more or less constant for years (1), but the scale of publicity it drew to the use of force in American policing. Such shootings are only the highly visible top of a spectrum of perceived police abuses of authority, beginning with asserting dominance via demeaning, disrespectful, and harassing treatment and escalating to involve the use of clubs, tasers, and, in some cases, guns. The justifiability of any particular instance of the use of force can be debated, but there have been a number of suggestions that the police in America today overuse command and control techniques, which emphasize dominance via the threat or use of force, and that better strategies for managing interactions with the public in ways which build public trust and deescalate hostility and conflict need to be identified and incorporated into American policing (2–6).

The case for developing new strategies for policing is articulated in President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing report (7). This report argues that popular legitimacy should be the first pillar of contemporary policing. It has led to efforts to identify ways to implement this agenda by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (8) and by the US Department of Justice (9). This examination of the research literature suggests that a promising strategy for building popular legitimacy is procedural justice policing, a model of policing which emphasizes listening and responding to people in the community, explaining police policies and practices in interactions with civilians, and treating the public with dignity, courtesy, and respect (10). The procedural justice model is built around developing consensus and cooperation with the community. A variety of research of the police suggests that procedural justice policing can build popular legitimacy and heighten willing deference and cooperation (2, 11, 12).

As with any policing reform effort, a key issue is the feasibility of implementing this change in policing culture. In this case, the question is whether police officers can be trained to adopt a new style of policing and, if so trained, whether they will change their behavior in ways that diminish the number of interactions in which civilians experience what they feel is disrespectful treatment (13) or the unjustified use of force by the police. Translating from evidence-informed policies to the adoption of new policing strategies has long been a major challenge in American policing. One common tactic is officer retraining. Indeed, saying that a problem is being addressed by retraining is a common leadership response to crises. Unfortunately, such retraining efforts often go unevaluated (14), and it is unclear if an actual change in on-the-job officer behavior has occurred.

This study evaluates a major effort to implement officer retraining in procedurally just policing practices by the Chicago Police Department (CPD). The CPD created a 1-d Procedural Justice training program for their training academy and then assigned the vast majority of serving officers to participate in that training. The training program emphasized the importance of voice, neutrality, respect, and trustworthiness in policing actions. Officers were encouraged to provide opportunities for civilians to state and explain their case before making a decision, apply consistent and explicable rules-based decision-making, treat civilians with dignity and respect their status as community members, and demonstrate willingness to act in the interests of the community and with responsiveness to civilians’ concerns.

The rollout of the training program created an opportunity to test the impact of training upon police behavior as reflected in complaints about the police and mandatory use of force reports. The procedural justice training syllabus highlights the importance of interpersonal aspects of policing interactions and provides officers with detailed templates for approaching civilians in ways that are respectful and minimize conflict, which should reduce the frequency of interactions in which civilians feel that they have been treated with discourtesy or disrespect. The training syllabus also emphasizes behavioral models that avoid force escalation and instead gain compliance through nonforceful approaches, reducing the likelihood that officers will rely on the use of force in civilian interactions.

The key question is whether police training can change police behavior. Several efforts to evaluate procedural justice training provide tentative evidence that it can. Skogan et al. (15) found that participation in the Chicago training program studied here increased police officers’ expressed support for using procedural justice strategies in the community. Rosenbaum and Lawrence (16) found that procedural justice training changed cadet behavior during scenarios involving interactions with people in the community. Antrobus et al. (17) found similar positive effects of procedural justice training on officer attitudes and on-the-job behavior in a sample of Australian police officers. And Owens et al. (18) found that procedural justice training led to lower levels of use of force against people in the community among a group of Seattle police officers.

While each of these studies supports the value of procedural justice training, they have important limits. Only two consider behavior in the community, and both of these use small samples (16, 18). Further, Owens et al. (18) focus upon one-on-one training by a supervisor for officers engaging in civilian encounters in small geographic areas, or “hot spots,” with high crime rates. None of these studies speaks to the key policy question: Can a police department change the nature of officer behavior across a large number of officers using a training program that can realistically be implemented? In the current study, the intervention was possible because officers were only taken out of the community for one training day. Without a viable training model, the call for strategies that involve building popular legitimacy must look at other avenues besides training to change police behavior. At this time, there is not strong evidence that training can influence general police behavior in the field.

Results

We evaluated the rollout of procedural justice training in the CPD to conduct a broad assessment of changes in officer field behavior. Beginning in January 2012 and continuing through March 2016, the CPD assigned 8,480 officers to a 1-d training session on procedurally just policing strategies. A further 138 officers were trained after March 2016, when the evaluation period ended. In the training session, officers were introduced to the various ideas associated with procedural justice and its implementation in their everyday work. See SI Appendix for the training syllabus and an overview of the training implementation.

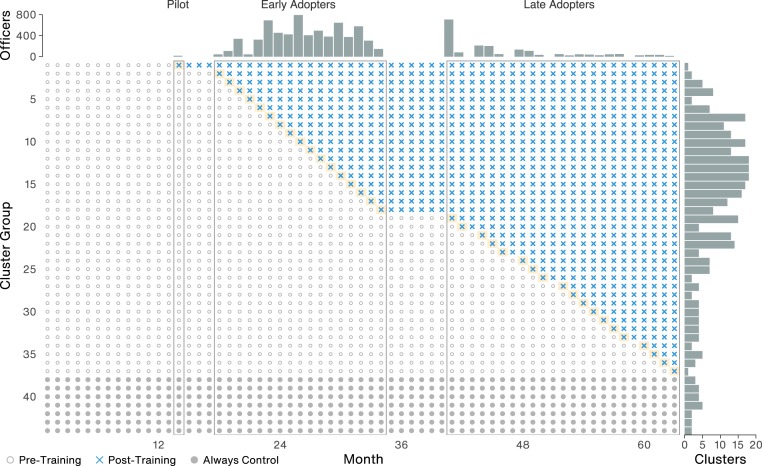

The rollout of training constitutes a staggered adoption design where, instead of units being assigned to a treatment arm and a control arm at a fixed point in time, all officers are assigned to training, but the date on which training is undertaken varies. Once trained, officers remain in the trained condition thereafter. Fig. 1 shows the staggered adoption of training. Following a pilot training session in month 13, the rollout occurred in two phases, from months 18 to 34 and 41 to 63. SI Appendix contains further details on the staggered adoption of training and a graphical summary of the training rollout. To evaluate the effects of training on officer behavior, we combined information about when officers participated in training with records of complaints regarding officer conduct, settlement payouts following civil litigation, and mandatory officer-filed use of force reports.

Fig. 1.

The staggered adoption of procedural justice training in the CPD; 8,480 officers were trained in 305 clusters across 49 mo. Once trained, clusters shift from the pretraining to posttraining condition. The rollout consisted of an initial pilot training program in month 14, followed by a first training phase from months 18 to 34, a 6-mo period in which no training occurred, and a second training phase from months 41 to 63. The study period ends at month 63, the last month for which outcome data are available, such that the 22 clusters trained after month 63 remain in the control condition throughout. The frequency of officers trained per month is shown in the top margin. In this visualization, we grouped clusters by the month in which they were trained. The frequency of clusters per training month is shown in the right margin.

To estimate the effect of training on these outcomes, we clustered officers according to the date on which they participated in procedural justice training. For the 8,618 officers nested in the training clusters, we obtained data on all complaints received and all mandatory use of force reports filed in each of the mo from January 2011 to March 2016. We obtained data on whether complaints were sustained or resulted in a settlement payout for the mo from January 2011 to October 2015. In the resulting time series cross-sectional data, , we consider inference on the training effect as a problem of counterfactual estimation in which we seek to ascertain what the posttraining observations would have been under the counterfactual scenario in which the cluster had not been trained. By leveraging variation in the timing of training due to the staggered adoption, we draw on the full observed data to establish the counterfactual: Within each cluster, the pretraining observations inform the posttraining counterfactual estimates; within each month, clusters in the pretraining condition act as controls for clusters in the posttraining condition. For complaints and use of force, the 22 clusters containing 138 officers trained after March 2016 remain in the control condition throughout the evaluation (Fig. 1). For sustained and settled complaints, 33 clusters containing 244 officers trained after October 2015 remain in the always-control condition. If training reduced police misconduct and use of force, then we would expect the observed frequency of complaints, sustained or settled complaints, and force reports for trained clusters to be lower in the posttraining periods than the counterfactual estimates .

We estimate the training effects using an interactive fixed effects (IFE) model (19). We present estimates of the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) per 100 officers per month as well as the cumulative ATT, which represents the total change in complaints, sustained or settled complaints, or use of force in the 24 mo following training. Details on the IFE model are provided in Materials and Methods.

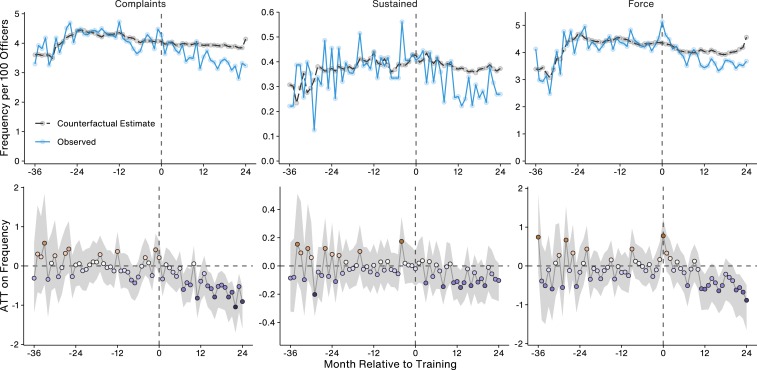

The results of our evaluation indicate that procedural justice training was successful in reducing police misconduct as measured by the frequency of complaints filed against officers. Table 1 reports that training reduced the frequency of complaints received by −11.6 (95% CI: −15.60, −7.45; SE = 2.09; ) per 100 officers in the 24 mo following training. A total of 6,577 complaints were filed against trained officers in the 24 mo after training. We estimate that 7,309 complaints would have been filed without training, a 10.0% reduction equivalent to approximately 732 fewer complaints. During the posttraining period, the CPD received 3.49 complaints per 100 officers per month compared to 4.03 that would have been received in the absence of training. Fig. 2 shows that the observed count and counterfactual count of complaints closely match in the pretraining period before diverging after training is introduced, indicating a valid counterfactual basis for estimating the training effect.

Table 1.

Average effect of training on complaints received, sustained or settled complaints, and mandatory reports of use of force

| Complaints | Sustained | Force | |

| Cumulative ATT | −11.60 | −1.67 | −7.45 |

| SE | 2.09 | 0.61 | 2.33 |

| 95% CI | −15.60, −7.45 | −2.81, −0.40 | −12.40, −3.37 |

| P | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.002 |

| Cluster fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Month fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Officers | 8,618 | 8,618 | 8,618 |

| Months | 63 | 58 | 63 |

| Clusters | 328 | 328 | 328 |

| Treated clusters | 306 | 295 | 306 |

| Always-control clusters | 22 | 33 | 22 |

| Observations | 20,664 | 19,204 | 20,664 |

The cumulative ATT represents the average reduction after 24 mo per 100 trained officers. The 95% CIs are computed using 2,000 block bootstrap runs at the cluster level.

Fig. 2.

(Top) Observed and counterfactual estimates of complaints, sustained or settled complaints, and use of force per 100 officers per month. Months are recalibrated to be relative to the onset of training. (Bottom) The ATT for each month is the estimated counterfactual frequency subtracted from the observed frequency in that month. Monthly ATT estimates are colored according to their value relative to zero. The 95% CIs are computed using 2,000 block bootstrap runs at the cluster level.

A key indicator that procedural justice training reduced misconduct is that it reduced the number of complaints that trained officers received. However, it is important to recognize that complaints reflect civilian assessments regarding the inappropriateness of police behavior. These assessments may or may not align with legally or procedurally inappropriate police behavior. Fortunately, we also have records on whether a complaint was sustained or resulted in a settlement payout (20). In Chicago, complaints are investigated by either the Independent Police Review Authority or the CPD’s Bureau of Internal Affairs, which recommend whether complaints should be sustained, before a final decision is issued following CPD review. Similarly, prior to settling a case and paying damages, there is an independent evaluation of the merit of a complaint. Although there are obstacles to pursuing a settlement and racial disparities in the dispositional outcomes of complaints (21), and the investigation of complaints is often forestalled by the absence of a signed affidavit, sustained or settled complaints reflect police behavior that has been demonstrated to violate legally or procedurally justified conduct.

We estimate that training reduced the frequency of sustained or settled complaints by −1.67 (95% CI: −2.81, −0.40; SE = 0.61; ) per 100 officers in the 24 mo following training. Among posttraining officers, 573 complaints were sustained or resulted in a settlement related to misconduct, with settlement payouts totaling $22.9 million. Without training, we estimate there would have been an additional 105 sustained or settled complaints, a reduction of 0.07 per 100 officers per month. This corresponds to a 15.5% reduction from 0.39 to 0.32 sustained or settled complaints per 100 officers per month.

The procedural justice training program was also effective in reducing the frequency with which officers resorted to using force in civilian interactions. Table 1 reports that training reduced mandatory use of force reports by −7.45 (95% CI: −12.40, −3.37; SE = 2.33; ) per 100 officers in the 24 mo after training. During this 2-y period, officers reported using force in 7,116 incidents ranging in severity from a takedown to a firearm discharge (SI Appendix). We estimate that, in the absence of training, there would have been 486 additional uses of force totaling 7,602. This 6.4% reduction in force corresponds to a rate of 3.77 per 100 officers per month in the posttraining period, down 0.40 from the 4.17 expected under the counterfactual of no training. Fig. 2 shows a similar average observed and counterfactual use of force in the pretraining period, again diverging only after training was introduced. In SI Appendix, we report that procedural justice training reduced use of force actions with weapons, but did not cause a decline in either force mitigation efforts or control tactics, indicating that procedural justice training may have deterred officers from the escalation of force.

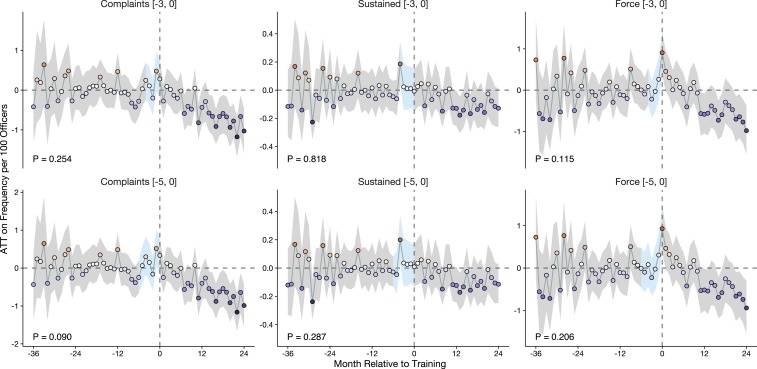

To test whether the estimated effect of training may be affected by time-varying confounding, we carried out placebo tests in which we artificially introduced training 3 mo before each cluster was, in fact, trained (22). We then estimated the placebo training effect in the 3 mo prior to training. As the clusters had not yet undergone training, there should be no evidence for a training effect in this 3-mo placebo period. If there is evidence for a placebo effect, the estimated counterfactual may not be an adequate comparison for the observed outcomes after training. Fig. 3 shows that the complaints, sustained or settled complaints, and use of force models pass the placebo test, indicating that the estimated counterfactual provides a valid basis for identifying the training effect. The values for the placebo ATT in the 3 mo before training was, in fact, introduced are , , and for complaints, sustained or settled complaints, and force, respectively. We also find no evidence for a placebo effect in the period 5 mo before the true onset of training.

Fig. 3.

Placebo tests for the effect of training on complaints, sustained or settled complaints, and use of force. In the placebo tests, the training is artificially introduced before the observed onset of training. The placebo ATT is estimated for the period between the artificial onset and the true onset, denoted by the blue region. The P value for the placebo ATT is shown. (Top) Training is artificially introduced 3 mo before the true onset, and the placebo ATT is calculated for the period −3 mo to 0 mo. (Bottom) Training is artificially introduced 5 mo before the true onset, and the ATT is calculated for the period −5 mo to 0 mo. For all outcomes, we find no evidence for an effect of training in the placebo period, and the models pass the placebo test. The 95% CIs and values are computed using 2,000 block bootstraps at the cluster level. The uncertainty for the placebo ATT is larger than the ATT in the full data because the placebo tests are informed by fewer observations in the pretraining condition.

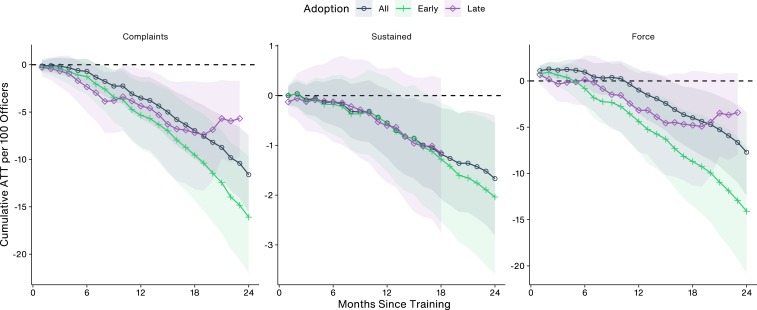

Lastly, Fig. 4 shows that the effect of procedural justice training was durable, reducing complaints and use of force throughout the 24 mo following training. The cumulative ATT is monotonically decreasing for all three outcomes in the model including all trained and control clusters. The durability of the effect on complaints and use of force indicates that procedural justice can elicit a behavioral shift beyond the days and weeks following training.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative ATT per 100 officers in the 24 mo after training by adoption time. The cumulative ATT represents the total reduction in each outcome in the months since the onset of training. Early adopters are those officers trained in the first training phase, encompassing the first 17 mo of the rollout. Late adopters were trained in the second phase from months 41 to 63. The study period ends in month 63 for complaints and use of force and month 58 for sustained and settled complaints. Consequently, the cumulative ATT for late adopters extends for a maximum of 23 mo after training for complaints and use of force and 18 mo for sustained and settled complaints.

However, Fig. 2 shows that the ATT on complaints and use of force is heterogenous over time, with the average effect per 100 officers increasing in magnitude as the time since training grows longer. The reduction in complaints and force is most pronounced after 12 mo to 24 mo has passed since training. Importantly, the number of months that we observe clusters after training varies according to the adoption time of each cluster. Whereas early adopters are observed for at least 24 mo, late adopters are observed for between 1 mo and 23 mo, depending on when they were trained. Early adopters therefore make up a larger share of trained clusters in the 12 mo to 24 mo after training. The larger effect in this period suggests that training had a more pronounced effect on early adopters.

To examine heterogeneity in the training effect by adoption time, we estimated separate IFE models for early adoption clusters and late adoption clusters, retaining the always-control clusters in both models. Fig. 1 shows the early and late adoption periods. Fig. 4 shows that the effect was more pronounced on early adoption clusters. After 18 mo, early adopters had 9.54 fewer complaints, 1.28 fewer sustained and settled complaints, and 8.72 fewer uses of force per 100 officers compared to 6.04, 0.74, and 4.51 for late adopters, respectively. While the effect of training is durable, it caused a larger shift in behavior among officers trained early in the rollout. The complaints and use of force results are consistent across IFE and matrix completion (23) estimators; see SI Appendix.

Discussion

The force-based command and control model which is the dominant policing model in American policing is concerned with obtaining compliance through the threat or use of dominance and, if needed, coercion (24). This model has long been associated with public perceptions of mistreatment ranging from demeaning treatment to the excessive use of force. Recent discussions about policing emphasize the virtues of a new model of policing based upon procedural justice (2). Research points to desirable benefits from this type of policing, including heightened popular legitimacy, increased acceptance of police authority, and greater public cooperation with the police (15–18).

While empirical research findings suggest that the procedural justice model is preferable to the currently dominant command and control approach in terms of building public trust and promoting compliance and cooperation, its widespread adoption requires the identification of effective implementation models.

This study demonstrates the viability of one such model based upon officer training. The results indicate that training changes actual police behavior in desired ways while officers are in the field. Our findings are bolstered by the three separate outcome measures, which include complaints against police officers, complaints that were sustained or resulted in a settlement payout, and mandatory use of force reports filed by officers. Training reduced complaints against police, reduced demonstrated violations of legal or procedural rules, and reduced the frequency with which officers resorted to the use of force during interactions with civilians.

Importantly, the impact of training on complaints and use of force is durable, lasting at least 2 y. The staggered adoption of training enabled us to estimate the heterogeneity of the training effect by adoption time. The effect of training on late adopters was attenuated, suggesting there may be spillover effects in the rollout of training. That is, early adopters may have encouraged the take-up of procedural justice principles among late adopters prior to the latter group undertaking training, resulting in that training having a smaller effect at the time of delivery.

We anticipate that an evaluation of officer compliance with procedural justice methods in police–civilian interactions will be important for understanding the types of policing behaviors that were adopted and avoided to reduce complaints and the use of force. Further studies may also analyze the possibility of downstream effects associated with officer retraining, such as heightened top-down scrutiny, which may be important mechanisms for reducing misconduct and the use of force.

These results support efforts to change the culture of policing by demonstrating that realistic levels of training can produce substantial changes in police behavior on the streets.

Materials and Methods

Outcome Data.

Outcome data consist of 19,994 complaint records and 21,303 use of force reports, each of which are routinely collected by the CPD. A total of 1,699 of the complaints were sustained or resulted in a settlement payout. The complaints and use of force data cover the period from January 2011 to March 2016. The sustained and settled data cover the period January 2011 to October 2015. Each complaint record identifies the officer named in the complaint, the date of the incident, and the type of officer action that led to the complaint. The use of force reports, known as Tactical Response Reports (TRR) within the CPD, identify the officer filing the report, the date of the incident, and the type of force used. For any officer using force, it is mandatory to file a TRR under departmental policy. We report the count per officer and distribution of types of complaint and force used in SI Appendix.

The routine collection of these data means that our measurements of officer behavior are distinct from and blind to the training program. However, it is important to note that our measurements do not necessarily account for the full range of potential officer misconduct or use of force. Previous work suggests that many people who believe they were mistreated by the police do not file a complaint (25), and the process of filing a complaint can be costly and complicated (26). Although it is departmental policy to file a TRR if force is used, there is no guarantee that officers will comply in all cases.

The outcome data were obtained through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests by the Invisible Institute (http://invisible.institute). The outcome data have been released publicly and are available at https://github.com/invinst/chicago-police-data.

Training and Roster Data.

Training data were provided by the CPD. The training data contain the last name, first name, middle initial, scrambled employee number, and date of training for each of the 8,618 officers in the study. The outcome data contain a unique identifier for each outcome. We matched the training data to the outcome data using CPD roster data. The CPD roster data include officer last name, first name, and the unique identifier used in the outcome data. Employee numbers are protected under FOIA and could not be obtained. The training data contained 10,411 unique officers. From these, 10,285 could be matched to exactly one unique identifier; 23 (0.22%) did not have a name match in the roster data; and 103 (0.99%) could not be matched to exactly one officer in the roster data. The nonunique matches are due to name duplication where, for example, there are two or more officers named John Smith in the roster data and we could not determine which of these received training on a particular date. The 23 officers that did not have a name match in the roster data and 103 officers who could not be uniquely matched were excluded from the analysis.

Training continued beyond the study period when the curriculum was revised and retitled “A Tactical Mindset: Police Legitimacy and Procedural Justice.” Due to insufficient follow-up data, we could not evaluate the effects of this second, revised training module in the present study.

Data Exclusions.

In addition to exclusion due to incomplete name matching, we excluded 1,667 officers who were appointed to the CPD during the study period. One source of information underlying the counterfactual estimator, detailed below, is the frequency of each outcome in the months before the onset of training. Excluding new officers ensures that there exists at least 12 mo of pretraining control observations against which to benchmark the training effect; 94% of the excluded officers underwent training within 6 mo of appointment, which is the typical period an officer spends in the CPD Recruit Academy. As such, the appointment exclusion means that our estimates do not provide evidence on the effects of training new officers, but rather the effects of retraining serving officers. Our evaluation includes the remaining 8,618 officers who were retrained.

Statistical Analysis.

We clustered officers by the date on which they were trained. We then aggregated all complaints, sustained or settled complaints, and use of force reports by cluster in each month from January 2011 to March 2016, forming time series cross-sectional data. Our dependent variable is the frequency of complaints, sustained or settled complaints, or use of force reports per cluster-month. Each outcome is represented by a distinct outcome matrix containing these frequencies, with rows corresponding to clusters of officers and columns corresponding to months.

Each cluster has a training indicator in each month, which is if the cluster has been trained or if the cluster has not yet undergone training. Once a cluster has transitioned from to upon training, the cluster remains in the trained condition thereafter. The training condition for each cluster is represented by a matrix , which has the same dimension as the outcome matrix . The study period ends before the last 22 clusters are trained which therefore remain in the condition throughout. These always-control clusters ensure there are observations in the untrained condition in the latter months of the evaluation period.

To assess the training effect, for each outcome, we estimated a counterfactual matrix in which the elements are estimated counts under the scenario in which training had not taken place. To estimate the counterfactual matrix for each outcome, we used an IFE model (19, 27, 28). The IFE model is given by

| [1] |

where are the observed outcomes, such as the count of complaints received, for each cluster in each month , is an intercept, is a vector of factors representing the rollout of training, is vector of factor loadings which represent unobserved characteristics of the officer clusters and which allow for heterogenous training effects across clusters, and are cluster-specific errors (29). Through the interaction of the factors and factor loadings, the IFE estimator leverages observed patterns in counts within cluster over time and the patterns between clusters within time periods. Through , the estimator incorporates information on the known structure of the training rollout. The number of factors is selected using a cross-validation procedure. By conditioning on the factors and factor loadings, the IFE estimator relaxes the assumption of parallel trends required by alternative models such as difference-in-differences (19).

The IFE estimator produces a counterfactual matrix which we subtract from the observed matrix . The ATT is the mean difference between and in posttreatment months. Descriptively, this is the mean count of complaints per cluster-month that would have been received in the counterfactual condition in which training did not occur subtracted from the mean that we, in fact, observed in the posttraining period. We rescale the ATT to provide the effect per 100 officers per month rather than per cluster-month. For the cumulative ATT, we calculate the sum of the ATT over the 24 mo following the onset of training. A total of 575 officers ended employment at CPD between undertaking training and the end of the study period. We accounted for this source of attrition by updating the number of officers per cluster in each month. In SI Appendix, we show that the estimated effects are comparable if these 575 officers are excluded from the study. Standard errors and confidence intervals are computed using 2,000 block bootstraps at the cluster level (19).

To test for time-varying confounding in the pretraining trends in complaints and use of force, we conducted a set of placebo tests following the procedure introduced in Liu et al. (22). In the placebo tests, training is artificially introduced prematurely for each trained cluster. We run two separate tests with training introduced 3 mo early and then 5 mo early. In the absence of time-varying confounding, which is required for identifying the effect of training, there should be no discernible effect of training in the 3- or 5-mo placebo period before the training was, in fact, introduced. The placebo ATT is calculated using the IFE model following the procedure above. We interpret a large value as evidence against an effect of training in the placebo period.

Data Availability.

Data and code for reproducing the analyses presented in this paper are available on GitHub, https://github.com/george-wood/procedural_justice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Keniel Yao and Claire Ewing-Nelson for research assistance.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Data and code for reproducing the analyses presented in this paper are available on GitHub, https://github.com/george-wood/procedural_justice.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1920671117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zimring F., When Police Kill (Harvard, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tyler T. R., Goff P., MacCoun R., The impact of psychological science on policing in the United States: Procedural justice, legitimacy, and effective law enforcement. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 16, 75–109 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ariel B., Farrar W. A., Sutherland A., The effect of police body-worn cameras on use of force and citizens’ complaints against the police: A randomized controlled trial. J. Quant. Criminol. 31, 509–535 (2014). Correction in: J. Quant. Criminol.31, 509–535 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mummolo J., Militarization fails to enhance police safety or reduce crime but may harm police reputation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9181–9186 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legewie J., Fagan J., Aggressive policing and the educational performance of minority youth. Am. Socio. Rev. 84, 220–247 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyton K., Sierra-Arévalo M., Rand D. G., A field experiment on community policing and police legitimacy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 19894–19898 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing , “Final report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing” (Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Washington, DC, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lum C., et al. , An Evidence-Assessment of the Recommendations of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy, Fairfax, VA, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quattlebaum M., Meares T., Tyler T. R., “Principles of procedurally just policing” (Yale Law School, New Haven, CT, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyler T. R., Huo Y., Trust in the Law: Encouraging Public Cooperation with the Police and Courts (Russell-Sage Foundation, New York, NY, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyler T. R., Fagan J., Why do people cooperate with the police? Ohio State J. Crim. Law 6, 231–275 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyler T. R., Fagan J., Geller A., Street stops and police legitimacy: Teachable moments in young urban men’s legal socialization. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 11, 751–785 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voigt R., et al. , Language from police body camera footage shows racial disparities in officer respect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 6521–6526 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skogan W. G., Frydl K., Fairness and Effectiveness in Policing: The Evidence (National Academies Press, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skogan W. G., Van Craen M., Hennessy C., Training police for procedural justice. J. Exp. Criminol. 11, 319–334 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenbaum D. P., Lawrence D. S., Teaching procedural justice and communication skills during police-community encounters: Results of a randomized control trial with police recruits. J. Exp. Criminol. 13, 293–319 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antrobus E., Thompson I., Ariel B., Procedural justice training for police recruits. J. Exp. Criminol. 15, 29–53 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owens E., Weisburd D., Amendola K. L., Alpert G. P., Can you build a better cop? Experimental evidence on supervision, training, and policing in the community. Criminol. Publ. Pol. 17, 41–87 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y., Generalized synthetic control method: Causal inference with interactive fixed effects models. Polit. Anal. 25, 57–76 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rozema K., Schanzenbach M., Good cop, bad cop: Using civilian allegations to predict police misconduct. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 11, 1–47 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Headley A. M., D’Alessio S. J., Stolzenberg L., The effect of a complainant’s race and ethnicity on dispositional outcome in police misconduct cases in Chicago. Race Justice 10, 43–61 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L., Wang Y., Xu Y., A practical guide to counterfactual estimators for causal inference with time-series cross-sectional data. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3555463. Accessed 1 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Athey S., Bayati M., Doudchenko N., Imbens G., Khosravi K.. Matrix completion methods for causal panel data models. arXiv:1710.10251v2 (29 September 2018).

- 24.McCluskey J. D., Police Requests for Compliance: Coercive and Procedurally Just Tactics (LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC, New York, NY, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker S., Bumphus V. W., The effectiveness of civilian review: Observations on recent trends and new issues regarding the civilian review of the police. Am. J. Police 11, 1–16 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ba B., Going the extra mile: The cost of complaint filing, accountability, and law enforcement outcomes in Chicago. https://assets.aeaweb.org/asset-server/files/5779.pdf. Accessed 1 April 2020.

- 27.Bai J., Panel data models with interactive fixed effects. Econometrica 77, 1229–1279 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gobillon L., Magnac T., Regional policy evaluation: Interactive fixed effects and synthetic controls. Rev. Econ. Stat. 98, 535–551 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai J., Li K., Theory and methods of panel data methods with interactive fixed effects. Ann. Stat. 42, 142–170 (2014). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and code for reproducing the analyses presented in this paper are available on GitHub, https://github.com/george-wood/procedural_justice.