Abstract

The National Health Policy in India mentions equity as a key policy principle and emphasises the role of affirmative action in achieving health equity for a range of excluded groups. We conducted a scoping review of literature and three multi-stakeholder workshops to better understand the available evidence on the impact of affirmative action policies in enhancing the inclusion of ethnic and religious minorities in health, education and governance in India. We consider these public services an important mechanism to enhance the social inclusion of many excluded groups. On the whole, the available empirical evidence regarding the uptake and impact of affirmative action policies is limited. Reservation policies in higher education and electoral constituencies have had a limited positive impact in enhancing the access and representation of minorities. However, reservations in government jobs remain poorly implemented. In general, class, gender and location intersect, creating inter- and intra-group differentials in the impact of these policies. Several government initiatives aimed at enhancing the access of religious minorities to public services/institutions remain poorly evaluated. Future research and practice need to focus on neglected but relevant research themes such as the role of private sector providers in supporting the inclusion of minorities, the political aspects of policy development and implementation, and the role of social mobilisation and movements. Evidence gaps also need to be filled in relation to information systems for monitoring and assessment of social disadvantage, implementation and evaluative research on inclusive policies and understanding how the pathways to inequities can be effectively addressed.

Background

The social origins of ill health have been widely acknowledged in literature (1,2). Consequently, increasing attention has been given to addressing various social determinants of health that operate at individual and population levels (eg social position, access to education, occupation). Hilary Graham noted an ambiguity in public policies in countries that saw early social and economic change following rapid industrialisation (3). She found that despite an emphasis in these policies on the importance of the social determinants of health, at times they did not sufficiently acknowledge the underlying social processes that produce unequal distribution of these factors in the first place. She emphasised the need to recognise this distinction: between the determinants and the processes underlying their unequal and unfair distribution. An approach entirely driven by determinants is likely to fail to reduce health inequity despite resulting in overall improvement in population health outcomes. The subsequent development of the conceptual framework for action on social determinants of health by the World Health Organization both includes and distinguishes the determinants of health and those of health inequity (4). This framework considers a welfare state and redistributive policies as the most powerful determinants of health inequities.

In this sense, affirmative action for fairer distribution of resources relating to the social determinants of health is crucial in enhancing health equity. However, Burns and Schapper (5) as well as Bacchi (6) highlight that dominant discourses brand affirmative action as “preferential treatment” (often couched in language of equal opportunity policies) or simply “diversity management”. This interpretation effectively locates the “problem” within the social groups that are the targets of affirmative action, as if they inherently lacked “merit” and needed “help” to overcome their disadvantage. Such discourse importantly ignores the role of dominant groups in constructing ideas of “merit” and “assessment”, and the ethical implications of such constructs. These authors rather promote affirmative action as a means to address social injustice inflicted upon certain social groups, making a strong ethical case for such action (5,6).

India’s national health policy reflects a dual emphasis on addressing the social determinants of health and reducing health inequity. While the policy document does not elaborate on these issues, it mentions equity as one of ten key policy principles, emphasising that “reducing inequity would mean affirmative action to reach the poorest” (7). India has a long history of affirmative action policies addressing the distribution of some of the most significant determinants of health, such as education, employment and representation in electoral politics. However, attempts to evaluate these policies across sectors as means of reducing health inequities in India have been limited. This is supported by Ravindran and Gaitonde’s synthesis of health equity research in India since the year 2000 (8). A review of health inequality research in India in the past two and a half decades suggested that while the volume of research has increased to some extent there remains a dearth of studies that focus on the impact of policies/programmes, particularly in the context of marginalised communities (9). We, therefore, aimed to scope the research on available policies and their impact on the inclusion of minorities in public services in India. We also aimed to identify knowledge gaps in order to inform future research and practice agenda.

Methods

Context and scope of the study

The work we present in this paper was part of a collaborative project, “Strategic Network on Socially Inclusive Cities” a, with project partners in Asia (India, Vietnam), Africa (Kenya, Nigeria) and Europe (United Kingdom). The network aims to establish partnerships across stakeholders and promote learning across sectors/disciplines. It focuses on social inclusion of religious and ethnic minorities in a range of public institutions (especially related to health, education, police and governance) through mapping available evidence on the drivers of their exclusion, impact of inclusive policies, and areas that need further research.

In the Indian context, the network focused on officially recognised minorities and socially excluded groups to study the impact of prevailing affirmative action policies on their inclusion in education, health and governance. We originally intended to also explore police services but found insufficient published literature on this from India. Public services were conceptualised as a mechanism for stimulating social inclusion (10). The network used a broad interpretation of the term “policy” where the workshop participants deliberated on several inclusion strategies beyond legislative measures, such as the use of public interest litigation, community-led actions and social movements (11). However, this paper limits its scope to the affirmative action policies of governments through legislative and administrative means. We aim to better understand:

-

♦

the direct impact of these policies in achieving desired outcomes among the intended groups (especially religious and ethnic minorities);

-

♦

specific issues that hinder desired outcomes; and

-

♦

the research gaps/challenges with regard to the affirmative action policies in India.

Hence, we looked at the available evidence on whether and how affirmative action policies in areas of health, education, and governance directly benefited these groups. We acknowledge that a comprehensive assessment of the impact of such policies needs to go beyond examining the direct and immediate benefits among intended groups, which was the focus of this empirical enquiry. However, we were able to make some observations on indirect and long-term impacts of these policies while discussing the results.

Data collection and analysis

We used a review of the literature and a series of three multi-stakeholder workshops to develop a collective understanding of issues related to the social exclusion of minorities from select public services in India and identify a major research agenda for the future.

First, we initiated a scoping of relevant literature using different combinations of search terms (groups: scheduled caste, SC, scheduled tribe, ST, other backward caste, OBC, religion, ethnic, poverty, BPL and minority; policies: policy, program, service, scheme, affirmative action, reservation, quota, discrimination; sectors: health, medical, education, university, employment, job, government, election, assembly, panchayat; India). We searched select databases (IDEAS-RePEc, JSTOR, World Bank Open Knowledge Repository), a journal archive (Economic and Political Weekly), web portals of concerned government and non-government agencies, and used free internet searches.

The findings of the review were used as one of the inputs into a series of three workshops (May, September and December 2017). The workshops were half-day meetings of researchers, practitioners and policymakers from Karnataka who were engaged in social exclusion/inclusion related work and focused on themes of “social exclusion” (Workshop-1);“socially inclusive policies’”(Workshop-2); and “age, gender and migration” (Workshop-3) respectively. These workshops were aimed at promoting sharing and mutual learning from participants as well as an avenue to build an informal network. Workshop deliberations were summarised in the form of short workshop reports.

We used Nvivo to organise and code selected papers as well as workshop reports. We used thematic analysis identifying dominant themes that defined inclusive policies, their impact and major issues (design, implementation) with regard to these policies.

Results and discussion

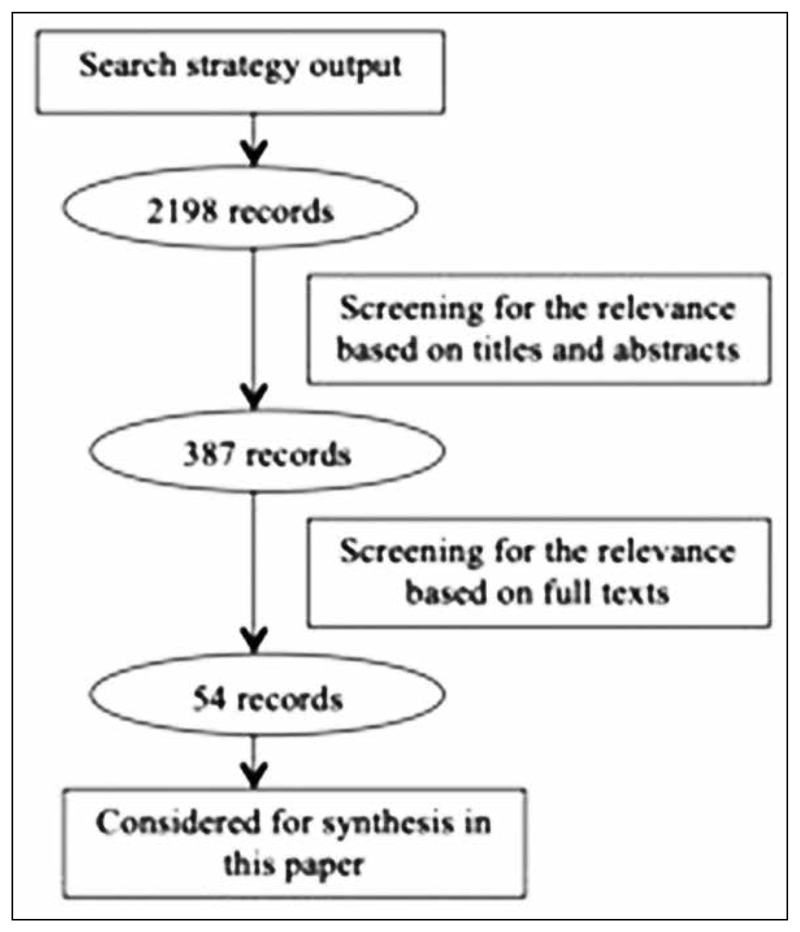

Figure-1 illustrates search strategy and outcomes. We retained 54 papers analysing inclusive policies based on primary/secondary data and critical commentaries.

Figure 1. Literature search strategy and outcomes.

Minorities

The term “minority” has varied interpretations, including a group that is smaller in size/numbers; has less power and representation; or is different in its identity from a larger and/or more powerful group in a society (12). In India, minority commissions identify minorities by statute at the national or state level. The National Minority Commission has notified Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Zoroastrians and Jains as minorities in this way. While there are no explicit criteria followed by these commissions, the designated minorities include a number of religious groups. There are ethnic minorities, which are not notified as such by these commissions, including several indigenous communities (often referred to as Scheduled Tribe statutorily or as adivasis in some states/regions), among others (Workshop-1).

In addition, governments in India recognise certain groups as having suffered social exclusion and consider them beneficiaries of affirmative action policies (13). Scheduled Castes (SC) is one such official category that includes (as per the law) lower caste groups among Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs that suffered from the dehumanising practices of untouchability and caste-based discrimination. Scheduled Tribes (ST) is another category that includes several indigenous communities that suffered disadvantage due to isolation. Finally, there are groups categorised as the Other Backward Class (OBC), who are deemed to suffer social disadvantage in general without any single defining criterion (unlike those in SC and ST). Many segments of the Muslim population come under the OBC category as a result of recognised social disadvantage

Affirmative action policies and their impact

In this section, we summarise the affirmative action policies and related evidence for each of the public service domains studied.

Education

A number of inclusive policies were identified, such as the reservation for admissions in government-funded higher education institutions for SC, ST and OBC. The constitution ensures government financial support for linguistic and religious minorities to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice. These institutions can disproportionately recruit students from particular minority communities.

In the last decade, the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act 2009b mandated the compulsory provision of free education to children between 6-14 years of age (for Classes1 to 8) by governments. This legislation also mandates private sector schools to reserve 25% of seats in Class-1 for children from disadvantaged communities and to teach them free of charge till Class-8. This section therefore supports many from ethnic and religious minorities to attend school when they may not have the financial capacity to do so otherwise. The Prime Minister’s 15-point programme for minorities, implemented by the national and state minority commissions, includes specific strategies for enhancing opportunities for the education of minorities (14). This includes enhancing equitable access to formal schooling and government schemes (like the Integrated Child Development Services), improving educational infrastructure and providing scholarships for meritorious students from minority communities.

Much of the literature focuses on reservations in higher education and consists of commentaries and viewpoints but with limited evidence. Studies, mostly looking at engineering institutions, have used measures assessing the three major aspects of this policy: (i) targeting: who is benefiting from these reservations? (ii) catch-up: how well do the students admitted against reserved seats perform academically? and iii) how do these students fare compared to the general category students in terms of timely completion of courses and getting jobs, or wages in the market?

These studies show that such reservations are generally well targeted. Students from SC and ST communities who were admitted against reserved seats were from poorer families and poorer districts compared to general category students (15–17). However, the targeting is poor when it comes to the OBC category (18). The OBC category includes groups with varying levels of disadvantage and there have been concerns that those from the “creamy” layer (relatively wealthy households within OBC) are capturing most of the reservation benefits to the exclusion of those who are more disadvantaged. In response, there have been proposals to create a sub-quota within the OBC category to avoid such elite capture (19). Because of poor targeting within this category, there is also a high political cost as the non-OBC feel they are more disadvantaged (18). Affirmative action policies for SC and ST have been in place in India since colonial times. Historically, there was limited political resistance to such quotas as they formed a small proportion of overall seats/jobs, remained largely unfilled, and as such did not result in the development of new political/power structures by these groups (20). However, extending affirmative action to OBC led to fierce opposition on several accounts: dominant groups worried about competition at senior levels for government jobs, and the dominance of an idea of “class” (from Marxist influence) as well as framing the idea of “caste” as being a complementary rather hierarchical social order (Gandhian influence) led to inadequate appreciation of caste-based oppression (20).

On the whole, the deficit in participation in higher education, defined as a difference between the proportion of specific groups (eg SC, ST) in the overall population and their proportion among the population currently enrolled in higher education has reduced, particularly for the SC, and is reducing at a faster pace for the ST (21). But while reservations, in general, seem to be helping enhance access to higher education for socially disadvantaged groups, a major challenge remains in ensuring their access to, and completion of school education (21). Suresh and Cheeran show that over a period of 50 years, the literacy gap between the ST and the total population in Kerala and at national level has been reduced but has not closed (22). In 1961, the literacy rate among ST in India was 8.53% as against the total literacy rate of 28.31%. In 2011, the ST literacy rate increased to 59% as against the total literacy rate of 74.4% (22). Furthermore, using data from 1981 to 2011, they highlight that the gender gap in literacy rate and educational attainments (men faring better than women) among the ST in Kerala reduced far more slowly as compared to the gender gaps among the overall population in Kerala (22).

There is generally a slower progression of students admitted against reserved seats compared to general category students, particularly for students admitted to selective majors (subject areas for which there is high competition for admissions) (15,16). This is because they often do not receive the additional support to enable them to “catch up” that these institutions are supposed to provide (16,23). That said, one study by Bagde et al, focusing on engineering institutions, revealed no adverse impact on graduation rates of reserved-category students, even when students opted for selective majors (17). The University Grants Commission has introduced schemesc to help disadvantaged students: (i) coaching classes for competitive exams (in 1984); (ii) remedial coaching at undergraduate and postgraduate levels (in 1994); and (iii) coaching classes for entry into services. However, the implementation of these schemes remains suboptimal. There is mixed evidence on timely completion of courses and wages earned in subsequent jobs. Robles and Krishna, in their specific study of an elite engineering institution, found that while there was no wage discrimination as such between reserved and non-reserved category students, there was a wage gap among reserved category students between those admitted into selective majors and those admitted to other subjects (15). So, while reservations helped students to secure admissions into selective majors, this did not translate into the positive financial outcomes expected.

Available literature on the impact of the Right to Education Act is limited. The workshop participants engaged in the education sector recognised the promise of such enabling legislation. However, they expressed concerns over suboptimal implementation of this legislation, especially among private schools in several states in India (Workshop-2). In general, there is some evidence of improvement in the net enrollment rate (from 84.5% in 2005-06 to 88.08% in 2013-14) and a marked reduction in the annual dropout rate (from 9.1% in 2009-10 to 4.7% in 2013-14) in primary education (24). However, between 2009-10 and 2013-14, the proportion of children from SC and ST communities in the total population of children enrolled remained unchanged. During this period, the proportion of children enrolled in primary education from Muslim communities went up marginally from 13% to 14% and that of children with special needs went up from 1.05% to 1.89% (24). However, there remains a huge regional disparity and gaps in the implementation of the legislation and consequently, in its impact. For example, in the year 2013-14, the proportion of seats reserved for children from economically weaker sections that actually got filled ranged from 2% in Odisha to 69% in Rajasthan (24). An ethnic or religious breakdown of this data was not readily available in the papers we reviewed. Of even greater concern is the fact that the learning outcomes seem to have deteriorated since the passing of the legislation. For example, the reading and basic mathematical competence among Class-1 to Class-5 children progressively declined between 2009 and 2012 (25).

We could not find empirical literature on the impact of the Prime Minister’s new 15-point programme for minorities instituted in 2005. Workshop participants reiterated that one of the major challenges is the lack of adequate efforts to spread awareness among minority communities about these opportunities/measures available to them (Workshop-2)

Governance

We use the term governance in a somewhat narrow sense and refer to two specific aspects. The first relates to the provision, in the Indian constitution, for a reservation of electoral constituencies (election seats) for SC and ST candidates in local (rural-panchayat/urban-municipality), state and national level elections. Since 1994, constitutional amendments also reserve 33% of the constituencies in local government elections for women candidates. The second aspect relates to government employees, who discharge government functions including public service provision. The workshop participants emphasised how while public service providers are crucial in realising the implementation of inclusive policies, they are also part of the wider Indian society and reflect the oppressive social norms that reproduce the marginalisation of certain groups (Workshop-3). Hence, it is important that members of the socially marginalised communities are represented among this category of employee (Workshop-3). The constitution provides for reservations for SC and ST candidates in government jobs in India. This is expected to enhance their representation in public services.

The few available studies examining the effect of political reservations for SC, ST and women candidates in general indicated a positive redistributive impact. These reservations are associated with a reduction in incidence, and to some extent intensity, of poverty among SC, ST and women, as well as among low income communities in general (26,27). This poverty reduction impact is more effectively realised in rural, as compared to urban constituencies, and is more pronounced in the case of SC and ST reservations compared to those for women (26,27). A study of ST reservations in the state assembly reveals similar positive findings, with an increase in targeted spending on tribal welfare programmes (28). Hence, these reservations are not just benefiting SC and ST individuals, but are more generally pro-poor measures.

There is a dearth of empirical data about the impact of the reservations in government jobs, partly because there has been much resistance in implementing such reservations (Workshop-2). For example, Delhi University specifically resisted reservations in teaching jobs till the late 1990s (23). Even when implemented, institutions often adopt methods such as post-based and promotion-based selection rather than an overall quota across posts that take years to effectively open up posts for the selection or recruitment of ST candidates (23). Strategies like the formation of SC/ST teachers associations and social and/or discrimination audits in educational institutions have been crucial in bringing these issues to light (23,29). Hence, while reservations in electoral constituencies seem to have a redistributive and poverty-reducing impact, the effectiveness of reservations in government jobs remains unclear.

Jaffrelot (20), in his incisive review of the impacts of affirmative action published in 2006, found that these policies had been valuable in terms of their political outcomes (in the form of political formations by marginalised caste groups, the fragmentation of political hegemony within the Congress party, and kindling hope and aspirations among lower caste groups) but had been very limited in terms of their positive socio-economic outcomes for the intended groups. In fact, he noted that quotas for jobs for SC, introduced since colonial times, remained largely unfilled due to the presence of indirect discrimination in the form of qualification barriers (as eligibility criteria) and lack of willingness on the part of authorities to fill them (20). For several decades, only the quotas for lower status government jobs were filled. Somewhat ironically, these were mainly positions as sanitation workers – occupations that marginalised groups were otherwise “destined for” in any case because of caste-based discrimination. The quotas for higher status civil service posts were not filled in any significant way till 1980s (20). While this situation has certainly changed, our findings still point to the limited direct impact of affirmative action, especially in the case of job quotas, but also a visible indirect impact through enhanced political representation of these groups, at least for SC and OBC.

Health

Unlike education, health is not a fundamental right in India, although Indian courts have interpreted right to health as part of Article 21 of the constitution that guarantees right to life and personal liberty (30). Consequently, there is no legislation that makes the right to health a justiciable right. There was a proposal to do so as part of the draft of the National Health Policy under discussion in the year 2015 (31). However, it was dropped in the final policy adopted in 2017 (7).

We could not find affirmative action policies in the health sector that specifically aim to benefit ethnic and/or religious minorities. However, several healthcare programmes/schemes exist that broadly target people living below the poverty line as well as people living in rural and difficult-to-reach locations. These groups contain a disproportionately higher representation of ethnic and religious minorities (Workshop-1). Furthermore, the reservations in medical education as well as the presence of minority-administered institutions operating in medical education should, in principle, enhance the representation of marginalised groups in healthcare workforce. Studies indicate that the discrimination in public healthcare delivery based on caste and social groups is a reality (32–34). There is underrepresentation of healthcare workers from marginalised social groups, more so in the cadres of physicians and surgeons (33,34). This is shown to be one of the factors that contribute to an environment leading to discrimination in healthcare delivery. In fact, Dreze and Sen (35) observed that one of the factors behind the better utilisation and performance of the public health system in Tamil Nadu is narrowing of “social distance” between doctors and patients with the recruitment of several doctors who are women and those coming from marginalised social groups.

More recently, government-funded health insurance/assurance schemes and the strategic purchase of healthcare services from private care providers have been the prominent government initiatives aimed at enhancing healthcare access among poor and marginalised communities (Workshop-2). The national government and several state governments have developed government-funded health insurance/assurance initiatives targeting the poor and occasionally other vulnerable communities. These initiatives have substantially enhanced insurance coverage among poorer sections of society. For example, the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana covered over 36.3 million households of the total 59.1 million households living below the poverty line by early 2017 (36). However, there is a long way to go. The National Sample Survey revealed that among the lowest quintile of the population (based on average monthly consumption expenditure), the government-funded insurance schemes the only major source of insurance for this segment covered only 10.1% of rural and 7.7% of urban Indians in the early 2014 (37). Moreover, recent studies point out that the scheme has not made any significant reduction in the incidence and the extent of out-of-pocket payments (38–40). These government-funded insurance schemes offer financial protection against hospitalisations but do not cover outpatient services. Studies also reveal that the target (intended) households face barriers at various stages (from enrollment to making insurance claims) of availing benefits under the insurance schemes (41). Further research is needed to evaluate the inclusion of minority ethnic and religious groups within these schemes, who are overrepresented in deprived populations (Workshop-3).

There is some evidence that broad reforms aimed at strengthening state health systems could reduce health inequities. A case study of Odisha (in eastern India) suggests that coordinating multiple health system strengthening strategies helped reduce inequities in maternal and nutritional health outcomes in the state (42). These strategies included: (i) political commitment translating into institutional response; (ii) geographic focus on districts with high SC and ST population and poor health indicators; (iii) health service delivery innovations; (iv) vulnerability mapping and context-based planning at sub-district level; (v) incentives to retain clinicians and expand the cadre of paramedics; and (vi) government initiated measures for financial protection for the health of disadvantaged communities.

This case study indicates the importance of developing a specific focus on addressing inequities using a range of strategies. By contrast, an excessive programmatic focus ignoring social, cultural and economic dynamics that creates unequal power, fundamental to creating inequities, could lead to the inclusion of minorities in public services but on highly adverse terms – a dynamic referred to as “adverse incorporation” (43). For example, ethnographic work examining the strategy of the polio immunisation programme targeted at underserved communities in the last remaining pockets of polio in rural north India (with a largely Muslim population) reveals that these intensive immunisation measures were often coercive, and did not address communities’ concerns about immunisation and/or demands for general healthcare services (44). Hence, a limited achievement in terms of better immunisation rate was fraught with the development of mistrust for health services/programmes among communities.

Intersectionality: Caste, class and gender

One of the criticisms of the reservation policy in India has been that it focuses on a single identity (being SC or ST or OBC) while people belonging to these groups are not equal in terms of the disadvantages they suffer. These disadvantages come from not just one of the group-level attributes but also from other group- and individual-level attributes.

As argued by Deshpande and Yadav, caste (socio-religious identity), class (economic) and gender closely intersect in defining outcomes of the reservation in higher education in India (18). Within each caste/socio-religious group, those in the higher economic classes do better compared to those in the lower economic classes. Within each economic class (except for the lowest economic class), those belonging to higher castes do better than those in lower castes. A gender gap in reservation benefits reflects the worst outcomes (except for higher economic classes among Christians) with women lagging behind in both low economic class and caste groups. The authors propose an alternative model for administering reservation policies that consider both, the group-level (class, caste, religion) and individual-level (family background, type of school attended) disadvantages to ensure that affirmative action is more effectively targeted and addresses more than just a singular caste (socio-religious) identity (18). Several studies point out that STs have not benefited as much as SCs from reservation policies in education, employment and elections. STs have not benefited adequately from the rights granted to them (with the ST quota often remaining underutilised) as well as in comparison with SCs (45). This may be explained by the relative lack of political identity, geographic fragmentation as well as the worldview and value system of adivasis (ST) that do not align with the very individualistic and competitive nature of efforts needed to access public institutions/services (45). Hence, focusing on reservations as a policy intervention in isolation can only have a limited impact.

Agenda for future research and practice

In the earlier sections, we summarised the available evidence on the direct impact of affirmative action policies. In this section, we outline the crosscutting themes across public services/institutions studied that have so far received the least attention and therefore ought to be considered in a future research and practice agenda for India. Given this dearth of literature, many of these recommendations evolved from the three workshops.

Policy implementation

The workshop participants recognised that several policy initiatives, including legislation, programmes, schemes, and administrative measures aimed at enhancing the inclusion of minorities in different public services, do not get adequately translated into practice (Workshop-2, 3). The reviewed literature also points to the fact that despite the persistence of disadvantage among minorities, affirmative action policies either do not adequately reach the intended communities and/or remain poorly utilised (eg reservation quota for STs). It is crucial to better understand implementation issues at different levels that explain the reach and utilisation of these policies. The limited implementation research available mainly uses quantitative measures (eg coverage rates of insurance schemes). While that is useful, there is also a need to understand who falls through the cracks during implementation and why, using more qualitative inquiry methods (Workshop-3).

Data and information systems

Data on the nature and extent of various forms of disadvantage suffered by population groups are very limited (Workshop-1). Even for the groups that have been the target of the prevailing affirmative action policies (ie SC, ST, OBC, religious minorities), there is a dearth of routinely collected information that can explain the dynamics of change in the disadvantages they suffer. There has been generally addition of social groups into these ‘rigid’ categories for affirmative action with a rare removal of any groups from these categories. Such a scenario also leaves room for a politics of appeasement (often referred to as “vote-bank politics”) rather than factual and need-based considerations for affirmative action (Workshop-2). Furthermore, the availability of such information would help understand inter-group as well as intra-group inequities and hence, help refine the design or targeting of inclusive policies. There is a need to evolve and refine the existing information systems to generate periodic and reliable information on social disadvantage.

Evaluation of inclusive policies

One of the major gaps in the available literature is the paucity of adequate evaluative research on policies that claim social inclusion as their primary outcome (Workshop-2). Even for the long-standing reservation policies examined in this paper, the scholarly literature is dominated by opinion pieces with very few studies evaluating these policies for their intended impacts. Despite challenges in studying complex public policies, there have been many advances on the methodological front in evaluating policy interventions (Workshop-2). What is specifically needed are research approaches and methods that not only identify what works but also explain what works for whom, how and in what context (46).

Research on private sector implementation

At present, the affirmative action policies initiated by the state are largely limited to the public sector. The private sector has become a major service provider, especially in areas like health and education, including for minorities (Workshop-2). Both for-profit and not-for-profit private sector entities play a key role in service provision to many disadvantaged groups. In fact, there is an increasing blurring of boundaries between public and private sectors where mere ownership might not be enough to understand the orientation of services towards those suffering exclusion (47). While the limited research available highlights some of the problematic issues of the commercial private sector, there is a need for further research to better understand the role played by heterogeneous non-state actors and how social inclusion could be promoted within and through the private sector (Workshop-2).

Social movements, community-engagement

The Workshop participants acknowledged that many social inclusion policies and more importantly, their implementation, are the result of strong social movements. They also acknowledged the differential impacts of social mobilisation/movements. While some groups (eg differently abled people) have been able to get organised and garner support from influential stakeholders in society to bring their demands into the public discourse, others struggle to get heard and remain at the fringes of policy discourse (Workshop-1, 2). Similarly, self-organisation of members of specific communities and their engagement in policy processes (at different levels, including forming/engaging with community-based institutions) have been crucial in demanding and achieving social justice. There is meagre research into the role of social movements, of social networks (for migrant and other vulnerable communities) and into the politics of community organisation/engagement (Workshop-2, 3).

Inequities

There is a growing focus on researching inequities across sectors. Literature and workshop deliberations around social exclusion pointed towards the need to use an intersectionality lens in researching inequities to ensure that such research helps develop a comprehensive picture of inequities experienced by individuals and communities instead of reducing inequities to analysis of single variables (Workshop-1, 2). It was also pointed out that some of the groups and/or settings (eg slums, those in state recognised categories of exclusion) remain a major focus of such studies while there is little work, if any, on many other groups (eg vulnerable migrant families living on private lands, stateless populations) (Workshop-1).

Intersectoral and interagency coordination

There are several actors and institutions engaged in governing and delivering basic services, welfare benefits and affirmative action. Tackling multiple intersecting sites of disadvantage (resulting in social exclusion) implies a need for coordination across agencies promoting social inclusion in different spheres of life. There is a growing body of research, mainly in high-income countries, on integrating health and social care (Workshop-2). Despite the acknowledgement of the need for such coordination, there is a dearth of research on feasible models for achieving intersectoral and interagency coordination that promotes the social inclusion of minorities (Workshop-2, 3).

Limitations

Our review is not exhaustive and was intended as exploratory, to scope the available literature and highlight trends affecting the social inclusion of minorities and excluded groups in India. Given the available time and resources for the evidence review, we were only able to look at the published literature and official reports. We didn’t review non-English literature and the few papers behind a paywall. We also limited participation in the workshops to stakeholders from Karnataka, which could potentially have limited the national relevance of these discussions. However, some participants worked on national issues and towards the end of the project, the first author also met civil society actors and representatives of the relevant government agencies in Delhi (National Commission on Scheduled Tribes; National Commission for Minorities) to share the project report and gather their feedback.

Conclusions

Affirmative action policies that aim to address social injustice and enhance equitable access to social determinants of health are an important determinant of health equity. India is known for its early reforms to bring in affirmative action. On the whole, the available empirical evidence on the uptake and direct impact of affirmative action policies for ethnic or religious minorities in the areas of education and governance is limited and was not found at all in relation to the health sector. Long-standing reservation policies in higher education and electoral constituencies have had a limited positive impact in enhancing access and in the representation of minorities. Electoral reservations seem to be a pro-poor measure but, as with other policies tackling poverty, better data is needed to understand intergroup differences within deprived populations. It is unclear how effective these approaches are for the inclusion of ethnic and religious minorities, who are overrepresented amongst deprived populations. The reservations in government jobs remain poorly implemented.

In general, class, gender and location further intersect creating an intra-group differential in the impact of the inclusive policies. There are inter-group differences with Scheduled Tribes lagging behind in comparison to Scheduled Castes in realising the positive impact of reservation policies. Several government initiatives aimed at enhancing the access of religious minorities to public services/institutions remain poorly studied for their impact. Future research and practice need to focus on neglected but relevant themes such as the role of private sector providers in supporting the inclusion of ethnic and religious minorities, the political aspects of policy development and implementation and the role of social mobilisation and movements. Evidence gaps also need to be filled in relation to information systems for monitoring and assessment of social disadvantage, implementation and evaluative research on inclusive policies and understanding how the pathways to inequities can be effectively addressed.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the members of the international- and Karnataka- Network on Socially Inclusive Cities, including the participants of the three workshops organised in Karnataka as part of the Indian component of the Socially Inclusive Cities Network project, for their valuable inputs. They also thank the two peer reviewers for their very useful comments on the manuscript.

funding support

The project activities (review of literature and stakeholder workshops) that this paper draws on were funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (UK) through a grant for the GCRF Socially Inclusive Cities Network (grant reference ES/P007384/1). Upendra Bhojani, NS Prashanth, and Pragati Hebbar were supported for their time through the Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance fellowships (IA/CPHI/17/1/503346, IA/CPHI/16/1/502648, and IA/CPHE/17/1/503338 respectively) awarded to them.

The submission is not under consideration for publication in any other journal. Summary of the content presented in this paper was presented as a poster in the 14th World Congress of Bioethics and 7th National Bioethics Congress.

Footnotes

Statement of competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

See University of Leeds website: https://medicinehealth.leeds.ac.uk/medicine/dir-record/research-projects/979/socially-inclusive-cities

The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009: http://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/The%20Right%20of%20Children%20to%20Free%20and%20Compulsory%20Education%20Act%2C%202009.pdf

See: UGC Guidelines for Coaching Schemes for SC/ST/OBC (Non-Creamy Layer) & Minorities for Colleges XII Plan (2012-17): https://www.ugc.ac.in/pdfnews/2722093_Guidelines-for-Coaching-Schemes-college.pdf

Contributor Information

Upendra Bhojani, Email: upendra@iphindia.org, Faculty & Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance Fellow, Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru, INDIA.

C Madegowda, Email: cmade@atree.org, Secretary, Zilla Budakattu Soligara Abhivruddhi Sangha, Chamarajanagar, INDIA; Senior Research Associate, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, Bengaluru INDIA.

NS Prashanth, Email: prashanthns@iphindia.org, Faculty and Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance fellow, Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru, INDIA.

Pragati Hebbar, Email: pragati@iphindia.org, Faculty & Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance Fellow, Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru INDIA.

Tolib Mirzoev, Email: T.Mirzoev@leeds.ac.uk, Associate Professor of International Health Policy and Systems, Nuffield Centre for International Health and Development, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Saffron Karlsen, Email: s.karlsen@ucl.ac.uk, Senior Lecturer, School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

Ghazala Mir, Email: G.Mir@leeds.ac.uk, Associate Professor, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

References

- 1.Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43943/9789241563703_eng.pdf;jsessionid=85DD6533CBA664FBB77B0038ADEBDB75?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkinson R, Marmot M. Social Determinants of health: the solid facts. 2nd ed. World Health Organization; 2003. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0005/98438/e81384.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham H. Social determinants and their unequal distribution: clarifying policy understandings. Milbank Q. 2004;82(1):101–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00303.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solar O, Irwin A. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice) Geneva: 2010. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Available from: https://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns P, Schapper J. The ethical case for affirmative action. J Bus Ethics. 2008;83:369–79. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacchi C. Policy and discourse: challenging the construction of affirmative action as preferential treatment. J Eur Public Policy. 2004;11(1):128–46. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Gol. National Health Policy 2017. New Delhi: MoHFW; 2017. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in//NHPfiles/national_health_policy_2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravindran TKS, Gaitonde R, editors. Health Inequities in India: a synthesis of recent evidence. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhan N, Rao KD, Kachwaha S. Health inequalities research in India: A review of trends and themes in the literature since the 1990s. [cited 2019 Feb 14];Int J Equity Health. 2016 15:166. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0457-y. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerometta J, Häussermann H, Longo G. Social innovation and civil society in urban governance: strategies for an inclusive city. Urban Stud. 2005 Oct 42;(11):2007–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mir G, Karlsen S, Mitullah W, Ouma S, Bhojani U, Okeke C. Achieving SDG 10: A global review of public service inclusion strategies for ethnic and religious minorities. Draft paper presented at the UNRISD conference; Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development; 2018. [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: http://www.unrisd.org/80256B42004CCC77/(httpInfoFiles)/FFE23E8144F5A514C1258339005A4796/$file/OvercomingInequalities2b_Mir---Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Heritage Dictionary of the English Langauge. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company; 2016. Available from: https://ahdictionary.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Commision for Religious and Linguistic Minorities. Report of the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities. Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India; 2007. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.minorityaffairs.gov.in/reports/national-commission-religious-and-linguistic-minoritie. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Minority Affairs. Guidelines for implementation of Prime Minister’s new 15 point programme for the welfare of minorities. Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India; [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.minorityaffairs.gov.in/sites/default/files/pm15points_eguide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robles VCF, Krishna K. Affirmative action in higher education in India: targetting, catch up, and mismatch. NIBER Working Paper; 2012. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Report No: 17727. Available from: https://nber.org/papers/w17727%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/40657666%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org.mutex.gmu.edu/stable/pdfplus/40657666.pdf?acceptTC=true. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagpurkar S. Are we ready as enough is not enough? Indian J Soc Dev. 2011;11(2):667–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagde BS, Epple D, Taylor L. Does affirmative action work? Caste, gender, college quality, and academic success in India. Am Econ Rev. 2015 Dec 16;106(6):1495–521. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deshpande S, Yadav Y. Redesigning affirmative action: castes and benifits in higher education. Econ Polit Wkly. 2006 Jun 17;41(24):2419–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Commission for Backward Classes. Report relating to the proposal for the sub-categorization within the Other Backward Classes. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowernment, Government of India; 2015. Mar 2, [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.ncbc.nic.in/Writereaddata/ReportoSub-CategorizationwithinOBCs-2015-Pandey635681469081640773.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaffrelot C. The impact of affirmative action in India: more political than socioeconomic. India Rev. 2006;5(2):173–89. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basant R, Sen G. Who participates in higher education in India? rethinking the role of affirmative action. Econ Polit Wkly. 2010 Sep 25;45(39):62–70. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suresh PR, Cheeran MT. Education exclusion of Scheduled Tribes in India. Int J Innov Res Dev. 2015;4(10):135–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xaxa V. Ethnography of reservation in Delhi university. Econ Polit Wkly. 2002 Jul 13;37(28):2849–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.KPMG & Confederation of Indian Industry. Assessing the impact of Right to Education Act. [cited 2019 Feb 14];2016 Mar; Available from: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/03/Assessing-the-impact-of-Right-to-Education-Act.pdf.

- 25.Woodrow Wilson School of International and Public Affairs. Lessons in learning: an analysis of outcomes in India’s implementation of the Right to Education Act. [cited 2019 Feb 14];2013 Available from: http://wws.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/content/other/591h-Princeton_Lessons-in-Learning.pdf.

- 26.Kaletski E, Prakash N. Affirmative action policy in developing countries: Lessons learned and a way forward. [cited 2019 Feb 14];WIDER Working paper 2016/52 UNU-WIDER. 2016 Available from: https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/affirmative-action-policy-developing-countries. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chin A, Prakash N. NBER Working Paper. 16509. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2010. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. The redistributive effects of political reservation for minorities: Evidene from India. Available from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w16509. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pande R. Can mandated political representation increase policy influence for disadvantaged minorities? Theory and evidence from India. Am Econ Rev. 2003 Feb;93(4):1132–51. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khora S. Removing discrimination in universities. Econ Polit Wkly. 2016 Feb 6;51(6) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathiharan K. The fundamental right to health care. Indian J Med Ethics. 2003 Oct-Dec;4(11):123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Health Policy 2015, draft (placed in public domain for comments, suggestions, feedback) New Delhi: MoHFW, Government of India; 2015. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/showfile.php?lid=3014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baru R, Acharya A, Kumar AKS, Nagaraj K. Inequities in access to health services in India: caste, class and region. Econ Polit Wkly. 2010;XLV(38):49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 33.George S. Caste and care: is Indian healthcare delivery system favourable for dalits? Bangalore: ISEC; 2015. [cited 2019 Jul 24]. Report No.: 350. Available from: http://www.isec.ac.in/WP 350 - Sobin George.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shirsat P. The chronicle of caste and the medical profession in India. J Humanit Soc Sci. 2017;22(9):65–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dreze J, Sen A. India: development and participation. 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. Population, health and the environment; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna. Overview: Enrollment of Beneficiaries. [cited 2019 Feb 14]; Available from: http://www.rsby.gov.in/Overview.aspx.

- 37.National Sample Survey Office. Key indicators of social consumption in India - Health NSS 71st Round (January-June) 2014. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India: 2015. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available from: http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/national_data_bank/ndb-rpts-71.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karan A, Yip W, Mahal A. Extending health insurance to the poor in India : An impact evaluation of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana on out of pocket spending for healthcare. Soc Sci Med. 2017 May;181:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.053. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuppannan P, Devarajulu SK. Impacts of watershed development programmes: experiences and evidences from Tamil Nadu. [cited 2019 Feb 14];Agri Econ Res Rev. 2019 (22):387–96. Available from: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/18653/1/MPRA_paper_18653.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devadasan N, Seshadri T, Trivedi M, Criel B. Promoting universal financial protection: evidence from the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) in Gujarat, India. [cited 2019 Feb 14];Health Res Policy Syst. 2013 11 doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-29. Available from: https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1478-4505-11-29?site=health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thakur H. Study of awareness, enrollment, and utilization of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (National Health Insurance Scheme) in Maharashtra,India. [cited 2019 Feb 14];Front Public Heal. 2016 3 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00282. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4703752/pdf/fpubh-03-00282.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas D, Sarangi BL, Garg A, Ahuja A, Meherda P, Karthikeyan SR, et al. Closing the health and nutrition gap in Odisha, India: A case study of how transforming the health system is achieving greater equity. [cited 2019 Feb 14];Soc Sci Med. 2015 145:154–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.010. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hickey S, Toit A. Adverse incorporation, social exclusion and chronic poverty. Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working paper 81; 2007. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.chronicpoverty.org/uploads/publication_files/WP81_Hickey_duToit.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeffery P, Jeffery R. Underserved and overdosed? Muslims and the pulse polio initiative in rural north India. Contemp South Asia. 2011;19(2):117–35. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xaxa V. Protective discrimination: why scheduled tribes lag behind scheduled castes. Econ Polit Wkly. 2001 Jul 21;36(29):2765–72. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. Sage Publications Ltd: 1997. p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giusti D, Criel B, De Bethune X. Viewpoint: Public versus private health care delivery: beyond the slogans. Health Policy Plan. 1997;12(3):193–8. doi: 10.1093/heapol/12.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]