Abstract

Background

Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) tumor proportion score (TPS) is currently widely used for selection of immune therapies in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Most of samples for PD-L1 expression were obtained from tumor tissue. However, the feasible of malignant pleural effusion (MPE) cytological samples for PD-L1 detection is poorly reported. And the correlation between oncogene mutations and PD-L1 expression based on high-throughput sequencing is rarely studied.

Methods

NSCLC MPE cytological samples and partially paired tumor tissue from our institution analyzed for PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) using the clone SP263 pharmDx kit and evaluated genomic aberrations in all patients using next generation sequencing (NGS).

Results

One hundred and twenty-three MPE cell blocks and 29 paired tumor tissue were successfully tested for PD-L1 expression. PD-L1 TPS of ≥50% were seen in 18.7% (23/123) of all samples. The accordance of PD-L1 expression in tumor tissue and MPE samples was 86.2% (50% as cut-off value). PD-L1 TPS ≥50% tumors were significantly associated with EGFR wild-type (P=0.007), but, no correlation between other genes and PD-L1 expression. A trend of longer overall survival (OS) was observed in patients with PD-L1 TPS <50% than those TPS ≥50% (20.0 vs. 13.8 months, P=0.057). No difference of tumor mutational burden (TMB) was observed between patients with PD-L1 ≥50% and <50% (8.2/MB and 7.7/MB, P=0.47).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that cytological material is feasible for PD-L1 IHC analysis. Gene alterations could partially contribute to select the samples that with different PD-L1 expression. No correlation between the PD-L1 expression and TMB.

Keywords: Tumor proportion score (TPS), malignant pleural effusion (MPE), programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), oncogene mutations

Introduction

Patients of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harbored EGFR, ALK and ROS1 improved the overall survival (OS) and quality of life after the molecular targeted therapy (1-6). However, the survival in patients with wild-type of gene alternations was not improved recently. The anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitors, have been approved for systemic therapy in advanced NSCLC for remarkable efficacy compared with chemotherapy, especially in patients with PD-L1 tumor proportion scores (TPSs) of ≥50% (7-9). However, many questions are not well answered currently (10). PD-L1 detection was mostly based on tumor tissue in previous studies. It is not well known that whether the cytological samples could be used for PD-L1 detection. The relationship between EGFR/ALK mutations and PD-L1 expression was clearly investigated, while, the data based on high-throughput sequencing was scarce.

In present study, 123 malignant pleural effusion (MPE) samples were retrospectively analyzed for PD-L1 expression. Meanwhile, all of the samples were detected gene alterations with next generation sequencing (NGS) containing 416 genes. We aim to expound the feasibility of MPE samples for PD-L1 detection and investigate the correlation between oncogene mutations and PD-L1 expression.

Methods

Sample selection

Patients were enrolled in the study between Aug 2015 and Dec 2016. Eligible patients were aged at least 18 years and had advanced, non-squamous NSCLC with pleural effusion. All of the pleural effusion samples were confirmed as malignant by cytological smears. At the time of enrollment, the patients had not received targeted inhibitors. Patient exclusion criteria included squamous cell lung cancer, small cell lung cancer, or other metastatic malignancies tumor to the lung. Diagnosis of the tumors was performed by institutional pathologists with the accordance of the 2015 WHO classification. The study was approved by Zhejiang Cancer Hospital Ethics Committee (IRB2014-03-032). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Preparation of cell block and tumor PD-L1 analysis

About 50-mL fluid specimens were centrifuged at 2,500–3,000 rpm for 5 min. Cell sediments were then harvested, fixed with 3 times the volume of 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 60 min, wrapped in filter paper, and processed in an automatic tissue processor. The samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 4–5 mm.

Ventana independently stained all cases using PD-L1 IHC assay platforms. At Ventana, sections were stained with anti-PD-L1 (SP263, Roche) rabbit monoclonal primary antibody and a matched rabbit immunoglobulin G-negative control with an OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit on the BenchMark ULTRA automated staining platform. Three pathologists were independently evaluated all PD-L1 immunostained slides.

NGS analysis

Cell blocks were obtained and shipped to the central testing laboratory by required conditions. The tests were performed in Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc., China. Briefly, DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples. Purified DNA was qualified by Nanodrop2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and quantified by Qubit 3.0 using the dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sequencing libraries were prepared using the KAPA Hyper Prep kit (KAPA Biosystems) with an optimized manufacturer’s protocol. Customized xGen lockdown probes (Integrated DNA Technologies) targeting 416 cancer-relevant genes were used for hybridization enrichment (Table S1). The capture reaction was performed with the NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Hybridization and Wash Kit (Roche) and Dynabeads M-270 (Life Technologies) with optimized manufacturers’ protocols. Genomic fusions were identified by FACTERA with default parameters. Copy number variations (CNVs) were detected using ADTEx (http://adtex.sourceforge.net) with default parameters. Somatic CNVs were identified using paired normal/tumor samples for each exon.

Table S1. List of 416 cancer-related target genes with NGS detection.

| ABCB1 (MDR1) |

| ABCC2 (MRP2) |

|---|

| ADH1B |

| AFF1 |

| AFF4 |

| AIP |

| AKT1 |

| AKT2 |

| AKT3 |

| ALDH2 |

| ALK |

| AMER1 |

| APC |

| AR |

| ARAF |

| ARID1A |

| ARID2 |

| ARID5B |

| ASXL1 |

| ATF1 |

| ATIC |

| ATM |

| ATR |

| ATRX |

| AURKA |

| AURKB |

| AXIN2 |

| AXL |

| BAIAP2L1 |

| BAK1 |

| BAP1 |

| BARD1 |

| BCL2 |

| BCL2L11 (BIM) |

| BIRC3 |

| BLM |

| BMPR1A |

| BRAF |

| BRCA1 |

| BRCA2 |

| BRD4 |

| BRIP1 |

| BTG2 |

| BTK |

| BUB1B |

| c11orf30 |

| CBL |

| CBLB |

| CCND1 |

| CCNE1 |

| CD274 (PD-L1) |

| CD74 |

| CDA |

| CDC73 |

| CDH1 |

| CDK10 |

| CDK12 |

| CDK4 |

| CDK6 |

| CDK8 |

| CDKN1A |

| CDKN1B |

| CDKN1C |

| CDKN2A |

| CDKN2B |

| CDKN2C |

| CEBPA |

| CEP57 |

| CHD4 |

| CHEK1 |

| CHEK2 |

| CLIP1 |

| CLTC |

| COL1A1 |

| CREB1 |

| CREBBP |

| CRKL |

| CSF1R |

| CTCF |

| CTLA4 |

| CTNNB1 |

| CXCR4 |

| CYLD |

| CYP19A1 |

| CYP2A6 |

| CYP2B6*6 |

| CYP2C19*2 |

| CYP2C9*3 |

| CYP2D6*3 |

| CYP2D6*4 |

| CYP2D6*5 |

| CYP2D6*6 |

| CYP2D6*7 |

| CYP2D6*11 |

| CYP2D6*12 |

| CYP2D6*14 |

| CYP3A4*4 |

| CYP3A5*1 |

| CYP3A5*3 |

| DAXX |

| DCTN1 |

| DDIT3 |

| DDR2 |

| DENND1A |

| DHFR |

| DICER1 |

| DNMT3A |

| DPYD |

| DUSP2 |

| EGFR |

| EML4 |

| EP300 |

| EPAS1 |

| EPCAM |

| EPHA2 |

| EPHA3 |

| EPS15 |

| ERBB2 (HER2) |

| ERBB3 |

| ERBB4 |

| ERC1 |

| ERCC1 |

| ERCC2 |

| ERCC3 |

| ERCC4 |

| ERCC5 |

| ERG |

| ESR1 |

| ETV1 |

| ETV4 |

| ETV6 |

| EWSR1 |

| EXT1 |

| EXT2 |

| EZH2 |

| EZR |

| FANCA |

| FANCC |

| FANCD2 |

| FANCE |

| FANCF |

| FANCG |

| FANCL |

| FAT1 |

| FBX1 |

| FBXW7 |

| FEV |

| FGF19 |

| FGFR1 |

| FGFR2 |

| FGFR3 |

| FGFR4 |

| FH |

| FLCN |

| FLI1 |

| FLT1 (VEGFR1) |

| FLT3 |

| FLT4 |

| GATA1 |

| GATA2 |

| GATA3 |

| GATA4 |

| GATA6 |

| GNA11 |

| GNAQ |

| GNAS |

| GOLGA5 |

| GOPC |

| GRIN2A |

| GRM3 |

| GSTM1 |

| GSTP1 |

| GSTT1 |

| HDAC2 |

| HGF |

| HIP1 |

| HLA-A |

| HNF1A |

| HNF1B |

| HRAS |

| HSD3B1 |

| IDH1 |

| IDH2 |

| IGF1R |

| IGF2 |

| IKBKE |

| IKZF1 |

| IKZF3 |

| IL7R |

| INPP4B |

| INPP5D |

| IRF2 |

| JAK1 |

| JAK2 |

| JAK3 |

| JUN |

| KDM5A |

| KDM6A |

| KDR (VEGFR2) |

| KIF5B |

| KIT |

| KITLG |

| KLC1 |

| KLLN |

| KMT2A |

| KMT2B |

| KRAS |

| KTN1 |

| LHCGR |

| LMO1 |

| LRIG3 |

| LYN |

| LZTR1 |

| MAP2K1 (MEK1) |

| MAP2K2 (MEK2) |

| MAP2K4 |

| MAP3K1 |

| MAP4K3 |

| MAX |

| MCL1 |

| MDM2 |

| MDM4 |

| MED12 |

| MEF2B |

| MEN1 |

| MET |

| MGMT |

| MITF |

| MLH1 |

| MLH3 |

| MLLT1 |

| MLLT10 |

| MLLT3 |

| MLLT4 |

| MPL |

| MRE11A |

| MSH2 |

| MSH3 |

| MSH6 |

| MTHFR |

| MTOR |

| MUTYH |

| MYC |

| MYCL |

| MYCN |

| MYD88 |

| NAT1 |

| NBN |

| NCOA4 |

| NF1 |

| NF2 |

| NFKBIA |

| NKX2-1 |

| NOTCH1 |

| NOTCH2 |

| NPM1 |

| NQO1 |

| NR4A3 |

| NRAS |

| NSD1 |

| NTRK1 |

| PAK3 |

| PALB2 |

| PALLD |

| PARK2 |

| PARP1 |

| PARP2 |

| PAX5 |

| PBRM1 |

| PCDH11Y |

| PDCD1 (PD1) |

| PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2) |

| PDE11A |

| PDGFRA |

| PDGFRB |

| PDK1 |

| PGR |

| PHOX2B |

| PIK3C3 |

| PIK3CA |

| PIK3R1 |

| PIK3R2 |

| PKD1 |

| PKD2 |

| PKHD1 |

| PLAG1 |

| PLK1 |

| PMS1 |

| PMS2 |

| POLD1 |

| POLE |

| POLH |

| POT1 |

| POU5F1 |

| PPP2R1A |

| PRDM1 |

| PRF1 |

| PRKACA |

| PRKAR1A |

| PRKCI |

| PRSS1 |

| PTCH1 |

| PTEN |

| PTK2 |

| PTPN11 |

| PTPRD |

| QKI |

| RAC1 |

| RAD50 |

| RAD51 |

| RAD51C |

| RAD51D |

| RAF1 |

| RARA |

| RB1 |

| RECQL4 |

| RET |

| RHOA |

| RICTOR |

| RNF146 |

| RNF43 |

| ROS1 |

| RPTOR |

| RRM1 |

| RTEL1 |

| RUNX1 |

| SBDS |

| SDC4 |

| SDHA |

| SDHAF2 |

| SDHB |

| SDHC |

| SDHD |

| SEPT9 |

| SERP2 |

| SETBP1 |

| SETD2 |

| SF3B1 |

| SGK1 |

| SH2D1A |

| SHOX |

| SLC34A2 |

| SLC7A8 |

| SLX4 |

| SMAD2 |

| SMAD3 |

| SMAD4 |

| SMAD7 |

| SMARCA4 |

| SMARCB1 |

| SMO |

| SOX2 |

| SPOP |

| SPRY4 |

| SRC |

| SRY |

| STAG2 |

| STAT3 |

| STK11 |

| STMN1 |

| STRN |

| STT3A |

| SUFU |

| TACC1 |

| TACC3 |

| TEK |

| TEKT4 |

| TERC |

| TERT |

| TET2 |

| TFG |

| TGFBR2 |

| THADA |

| TMEM127 |

| TMPRSS2 |

| TNFAIP3 |

| TNFRSF11A |

| TNFRSF14 |

| TNFRSF19 |

| TNFSF11 |

| TOP1 |

| TOP2A |

| TP53 |

| TPM3 |

| TPM4 |

| TPMT*2 |

| TPMT*3 |

| TPMT*4 |

| TPMT*5 |

| TPMT*6 |

| TPMT*7 |

| TPMT*10 |

| TRIM24 |

| TRIM27 |

| TRIM33 |

| TSC1 |

| TSC2 |

| TSHR |

| TTF1 |

| TUBB3 |

| TYMS |

| UGT1A1 |

| VEGFA |

| VHL |

| WAS |

| WISP3 |

| WRN |

| WT1 |

| XPA |

| XPC |

| XRCC1 |

| YAP1 |

| ZNF2 |

| ZNF217 |

| ZNF444 |

| ZNF703 |

NGS, next generation sequencing.

TMB was defined as the number of somatic, coding, base substitution, and indel mutations per megabase of genome examined. For our panel TMB calculation, all base substitutions, including non-synonymous and synonymous alterations, and indels in the coding region of targeted genes were considered with the exception of known hotspot mutations in oncogenic driver genes and truncations in tumor suppressors. Synonymous mutations were counted in order to reduce sampling noise and known driver mutations were excluded as they are over-represented in the panel, as previously described (11).

Statistical methods

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. All P values reported are two-sided, and tests were conducted at the 0.05 significance level. The relationship between different groups was analyzed with chi-square tests. Progression-free survival (PFS) with targeted therapy was defined as the time from initiation targeted treatment to documented progression or death from any cause. PFS was plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method. All analyses were performed using SPSS® version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The last follow-up date was May 31, 2018. The median follow-up time was 20.2 months (range, 3.0–29.5 months). No patients were lost to follow-up.

Results

Baseline clinical and pathologic characteristics

Of the 123 patients analyzed, 65 were male and 58 of female with median age of 59 years old (range, 33 to 81 years old). Most of patients were with histology of adenocarcinoma (119 of 123). Fifty-one patients had smoking history and 72 were never smokers. The details of clinical and pathologic characteristics in present study were listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinicopathological characteristics of study participants.

| Variable | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 65 (52.8) |

| Female | 58 (47.2) |

| Age (years) | |

| ≥65 | 46 (37.4) |

| <65 | 77 (62.6) |

| Smoking history | |

| Yes | 51 (41.5) |

| No | 72 (58.5) |

| Performance status | |

| 0–1 | 106 (86.2) |

| 2 | 17 (13.8) |

| Metastatic status | |

| M1a | 73 (59.3) |

| M1b | 50 (40.7) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 119 (96.7) |

| Non-adenocarcinoma | 4 (3.3) |

| History of chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 37 (30.1) |

| No | 86 (69.9) |

PD-L1 expression in MPE samples and paired tumor tissues

Totally, 48 (39.0%) were with PD-L1 negative, followed by 1–5% (n=28), and PD-L1 TPSs of 5–49% (n=24). Twenty-three were with proportion of PD-L1 TPS of ≥50%. PD-L1 TPS ≥50% was seen significantly more frequently in smokers as compared to never smokers (P=0.01) and males (P=0.025). While not associated with patient tumor stage (P=0.53), age (P=0.85) and performance status (P=0.33) (Table S2).

Table S2. Comparison of clinical characteristics of PD-L1 TPS ≥50% versus TPS <50%.

| Variable | PD-L1 TPS ≥50% | PD-L1 TPS <50% | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.025 | ||

| Male | 17 | 48 | |

| Female | 6 | 52 | |

| Age, years | 0.85 | ||

| <65 | 14 | 63 | |

| ≥65 | 9 | 37 | |

| Smoking history | 0.01 | ||

| Yes | 15 | 36 | |

| No | 8 | 64 | |

| Metastasis site | 0.53 | ||

| M1a | 15 | 58 | |

| M1b | 8 | 42 | |

| Chemotherapy history | 0.33 | ||

| Yes | 5 | 32 | |

| No | 18 | 68 | |

| Performance status | 0.33 | ||

| 0–1 | 19 | 92 | |

| 2 | 4 | 8 |

PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

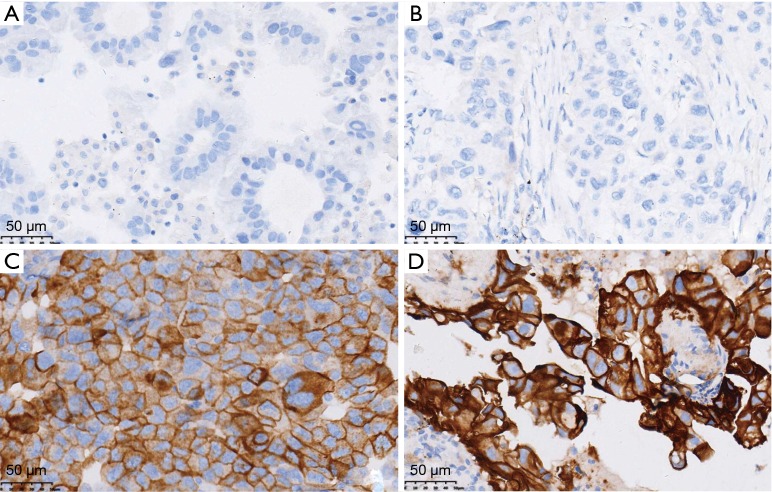

Twenty-nine patients were obtained the paired tumor tissue and with PD-L1 IHC detection (Figure 1). Among the 29 samples, 14 had PD-L1 TPS ≥1% in tumor tissue, and 11 in paired MPE samples, with agreement statistics of 69.0% (20/29) (Table 2). When 50% as cut off value, the accordance between MPE samples and tumor tissue was 86.2% (25/29) (Table 3). The details of comparison between MPE samples and tumor tissue was presented in Tables 2-4.

Figure 1.

PD-L1 expression in MPE samples (A,C) and paired tumor tissue (B,D) (A and B: TPS =0%; C and D: TPS =100%; IHC, ×400). PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; MPE, malignant pleural effusion; TPS, tumor proportion score; IHC, immunohistochemistry.

Table 2. PD-L1 expression in tumor tissue and paired MPE samples (a cut-off value of 1%).

| MPE | Tumor tissue | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | 8 | 3 | 11 (37.9) |

| Negative | 6 | 12 | 18 (62.1) |

| Total | 14 (48.3) | 15 (51.7) | 29 |

PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; MPE, malignant pleural effusion.

Table 3. PD-L1 expression in tumor tissue and paired MPE samples (a cut-off value of 50%).

| MPE | Tumor tissue | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | 5 | 1 | 6 (20.7) |

| Negative | 3 | 20 | 23 (79.3) |

| Total | 8 (27.6) | 21 (72.4) | 29 |

PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; MPE, malignant pleural effusion.

Table 4. PD-L1 expression in tumor tissue and paired MPE samples (a cut-off value of 10%).

| MPE | Tumor tissue | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | 8 | 1 | 9 (31.0) |

| Negative | 4 | 16 | 20 (69.0) |

| Total | 12 (41.4) | 17 (58.6) | 29 |

PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; MPE, malignant pleural effusion.

NGS results

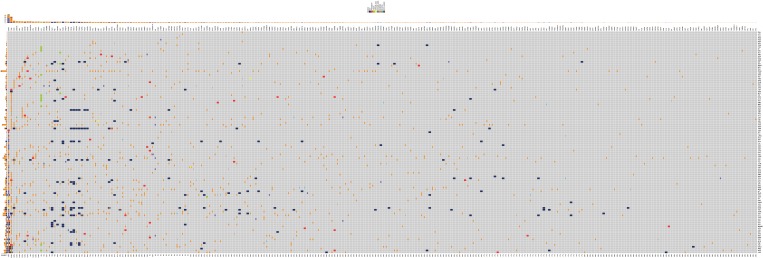

All results of the comparative analyses are presented in Figure 2. Overall, EGFR mutations were with most frequent (55.3%), followed with TP53 mutation (51.2%). Sixteen patients were found to harbor KRAS mutations, ALK rearrangement were observed in 11 patients. There was no ROS1 rearrangement, MET amplification and exon 14 skipping among the 123 samples.

Figure 2.

All of the gene alternations in 123 samples.

Association between PD-L1 expression and oncogene aberrations

Of the 68 patients with EGFR mutations, 10.3% of PD-L1 TPS ≥50%, while, the percentage of PD-L1 TPS ≥50% was 29.1% EGFR wild-type (P=0.007). Of 11 patients with ALK rearrangement, 9 had PD-L1 TPS <50%, as compared with only two tumors with PD-L1 TPS ≥50% (P=0.72). More patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50% in KRAS mutations than wild-type samples (25.0% vs. 17.8%, P=0.73) (Table 5 and Figure S1). The median TMB in samples with PD-L1 ≥50% and <50% was 8.2/MB and 7.7/MB, respectively (P=0.47).

Table 5. Correlation between common oncogene mutations or rearrangement and PD-L1 over-expression.

| Gene | Mutation | Wild-type | PD-L1 TPS ≥50% in mutation | PD-L1 TPS ≥50% in wild-type | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | 68 | 55 | 10.3% (7/68) | 29.1% (16/55) | 0.007 |

| ALK | 11 | 112 | 18.2% (2/11) | 18.8% (21/112) | 0.72 |

| KRAS | 16 | 107 | 25.0% (4/16) | 17.8% (19/107) | 0.73 |

| TP53 | 63 | 60 | 20.6% (13/63) | 16.7% (10/60) | 0.57 |

| KRAS/TP53 | 7 | 116 | 28.6% (2/7) | 18.1% (21/116) | 0.49 |

| RET | 3 | 120 | 33.3% (1/3) | 18.3% (22/120) | 0.93 |

| BRAF | 9 | 114 | 44.4% (4/9) | 16.7% (19/114) | 0.11 |

| ERBB2 | 7 | 116 | 0.0% (0/7) | 19.8% (23/116) | 0.42 |

| PIK3CA | 9 | 114 | 0.0% (0/9) | 20.2% (23/114) | 0.29 |

| STK11 | 6 | 117 | 16.7% (1/6) | 18.8% (22/117) | 0.68 |

PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

Figure S1.

Top 50 genes in patients with PD-L1 TPS <50% (A) and with PD-L1 TPS ≥50% (B). PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

PD-L1 expression and clinical treatment

Forty-seven patients with EGFR mutations received EGFR-TKIs treatment. The median PFS was 10.2 months (95% CI: 9.1–11.7 months). A trend of longer PFS was observed in patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50% (11.7 vs. 9.7 months, P=0.17). Forty-four patients received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, including 25 with pemetrexed and 19 of other regimens. No PFS difference was found between different regimens (7.0 vs. 6.5 months, P=0.97).

The median OS of all patients was 18.4 months (95% CI: 14.9–21.8 months). A trend of longer OS was observed in patients with PD-L1 TPS <50% than those TPS ≥50% (20.0 vs. 13.8 months, P=0.057) (Figure 3). No survival difference was observed in EGFR/ALK positive patients with PD-L1 TPS <50% than those TPS ≥50% (21.0 vs. 20.5 months, P=0.21); However, a shorter survival was existed in EGFR/ALK negative patients with PD-L1 TPS <50% than those TPS ≥50% (15.5 vs. 12.7 months, P=0.025).

Figure 3.

Overall survivals comparison in patients with different PD-L1 expression. PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1.

Discussion

A high accordance of PD-L1 expression was found between tumor tissue and cytological samples in present study. Further, we investigated the relationship between gene alternations and PD-L1 expression based on high-throughput sequencing. Our results demonstrated PD-L1 expression was associated with some oncogene aberrations.

Two platforms are currently applied in clinical practice for PD-L1 IHC detection, including DAKO and VENTANA (12-14). Patients with PD-L1 TPS of ≥50% were reported to benefit more from pembrolizumab treatment than chemotherapy in KEYNOTE024 study (7). And the PD-L1 TPS of ≥50% were reported in 20% to 30% of advanced NSCLC (7-9). The difference percentage may contribute to different antibodies in different trials. The Blueprint PD-L1 IHC Assay Comparison Project revealed that three antibodies (22C3, 28-8, SP263) were closely aligned on tumor cell staining, but different from SP142 (15). In present study, The PD-L1 TPS of ≥50% were found in 18.7% patients, which was a similar percentage compared with previous studies (16-18). And a high correlation between staining on cytological cell block material and histological specimens was observed. Our results indicated the feasibility of MPE samples for PD-L1 detection.

PD-L1 TPS of ≥50% in EGFR mutation patients were reported with 11% in Gainor et al. study (18). However, lung cancer patients harboring EGFR mutations are associated with lower response to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (usually lower than 5% in previous studies). Low rates of concurrent PD-L1 expression and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) may underlie these results. In present study, 10.3% EGFR-mutated samples were with PD-L1 TPS of ≥50%, in contrast, 29.1% of patients with EGFR wild type were with PD-L1 TPS of ≥50% which consistence with previous study. In another study, Dong et al. found that TP53 mutation significantly activated T-effector and interferon-γ signature. And TP53/KRAS co-mutated subgroup manifested exclusive increased expression of PD-L1 mutation burden (19). The reason may due to these two genes altered a group of genes involved in cell cycle regulating, DNA replication and damage repair, which results to a favorable efficacy to immune treatment. However, it is not clear for the correlation between TP53/KRAS and PD-L1 expression in Dong et al. study. In present study, no significant different was found between TP53/KRAS mutation. The small number patients may cause the bias.

As a retrospective nature, our study has several limitations. First, only 29 patients were with paired tumor tissue, hence, the accordance between tumor tissue and MPE sample could not fully validated in present study. Second, only the antibody of SP263 was used to examine the PD-L1 expression, which would be preferred for using another antibody to validate the results. In addition, although the 25% of TPS was recommended as cut-off value for durvalumab study (20). However, in the MYSTIC study, the data showed no more benefit for durvalumab than chemotherapy (21). Hence, 50% may be a preferable cut-off value regardless different antibody. For the purpose of comparison with other antibody, the 50% TPS was used in present study. Thirdly, no PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are approved in China, our data could not be examined in clinics. In additions, NGS in present study was not based on whole exome sequencing, the results based on 416 genes may not well represent the real TMB level, the relationship between PD-L1 and TMB needs to be investigated in future study. Last but not least, only 123 patients were collected in present study, hence, the correlation between rare oncogene mutations and PD-L1 expression was not fully investigate and the results might be affected.

In summary, our data suggests that MPE samples is feasible for PD-L1 IHC analysis. The PD-L1 levels of MPE cell blocks were comparable with paired tumor tissues, however, heterogeneity was found between these two media. Gene alterations based on NGS of MPE samples could contribute to select the samples that with different PD-L1 expression.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no: 81802276).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was approved by Zhejiang Cancer Hospital Ethics Committee (IRB2014-03-032). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2020.02.06). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009;361:947-57. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2380-8. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:121-8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu YL, Zhou C, Liam CK, et al. First-line erlotinib versus gemcitabine/cisplatin in patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: analyses from the phase III, randomized, open-label, ENSURE study. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1883-9. 10.1093/annonc/mdv270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:239-46. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi YK, Wang L, Han BH, et al. First-line icotinib versus cisplatin/pemetrexed plus pemetrexed maintenance therapy for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (CONVINCE): a phase 3, open-label, randomized study. Ann Oncol 2017;28:2443-50. 10.1093/annonc/mdx359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823-33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1837-46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00587-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med 2017;9:34. 10.1186/s13073-017-0424-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacher AG, Gandhi L. Biomarkers for the Clinical Use of PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Review. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1217-22. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rimm DL, Han G, Taube JM, et al. A Prospective, Multi-institutional, Pathologist-Based Assessment of 4 Immunohistochemistry Assays for PD-L1 Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1051-8. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerr KM, Nicolson MC. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, PD-L1, and the Pathologist. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016;140:249-54. 10.5858/arpa.2015-0303-SA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sholl LM, Aisner DL, Allen TC, et al. Programmed Death Ligand-1 Immunohistochemistry--A New Challenge for Pathologists: A Perspective From Members of the Pulmonary Pathology Society. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016;140:341-4. 10.5858/arpa.2015-0506-SA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch FR, Mcelhinny A, Stanforth D, et al. PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry Assays for Lung Cancer: Results from Phase 1 of the Blueprint PD-L1 IHC Assay Comparison Project. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:208-22. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ilie M, Khambata-Ford S, Copie-Bergman C, et al. Use of the 22C3 anti-PD-L1 antibody to determine PD-L1 expression in multiple automated immunohistochemistry platforms. PLoS One 2017;12:e0183023. 10.1371/journal.pone.0183023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rangachari D, VanderLaan PA, Shea M, et al. Correlation between Classic Driver Oncogene Mutations in EGFR, ALK, or ROS1 and 22C3-PD-L1 ≥50% Expression in Lung Adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:878-83. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1540-50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gainor JF, Shaw AT, Sequist LV, et al. EGFR Mutations and ALK Rearrangements Are Associated with Low Response Rates to PD-1 Pathway Blockade in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:4585-93. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong ZY, Zhong WZ, Zhang XC, et al. Potential Predictive Value of TP53 and KRAS Mutation Status for Response to PD-1 Blockade Immunotherapy in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:3012-24. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powles T, O'donnell PH, Massard C, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Durvalumab in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Updated Results From a Phase 1/2 Open-label Study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:e172411. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Planchard D, Yokoi T, Mccleod MJ, et al. A Phase III Study of Durvalumab (MEDI4736) With or Without Tremelimumab for Previously Treated Patients With Advanced NSCLC: Rationale and Protocol Design of the ARCTIC Study. Clin Lung Cancer 2016;17:232-236.e1. 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as