Abstract

User-defined mutagenic libraries are fundamental for applied protein engineering workflows. Here we show that unamplified oligo pools can be used to prepare site saturation mutagenesis libraries from plasmid DNA with near-complete coverage of desired mutations and few off-target mutations. We find that oligo pools yield higher quality libraries when compared to individually synthesized degenerate oligos. We also show that multiple libraries can be multiplexed into a single oligo pool, making preparation of multiple libraries less expensive and more convenient. We provide software for automatic oligo pool design that can generate mutagenic oligos for saturating or focused libraries.

Keywords: deep mutational scanning, directed evolution, nicking mutagenesis, oligo pools, saturation mutagenesis

Introduction

Directed mutagenesis is foundational for synthetic biology and protein engineering. Recent methods support the creation of large libraries of user-defined mutations in a single reaction (Firnberg and Ostermeier 2012; Wrenbeck et al. 2016a, 2016b; Cozens and Pinheiro 2018). Such protocols rely on annealing a short oligonucleotide to a parental template, wherein the oligo encodes a mutation by template mismatch. The complementary strand encoding the desired mutation is synthesized, after which the parental template strand is specifically destroyed. For large libraries, the mismatch is encoded using degenerate nucleotides, such that a single oligo can make up to 63 different mutations per codon substitution. However, degenerate oligonucleotides require hand-mixing to avoid over-representation of nucleobases (Firnberg and Ostermeier 2012) and are often unable to encode a desired subset of amino acids. Microarray-synthesized oligo pool technology has recently found use in synthetic biology (Kosuri and Church 2014), with multiple vendors offering relatively long oligos at moderate error rates. Clever techniques have emerged to use these pools for gene synthesis (Plesa et al. 2018), but the low femtomolar concentrations of individual oligos usually necessitates amplification and further processing from pools, limiting usability.

We recently described the Nicking Mutagenesis (NM, Wrenbeck et al. 2016a, 2016b) method to construct user-defined libraries in one pot using routinely prepared plasmid DNA. Because NM uses very low oligo concentrations, with the template in large excess to the mutational primer, we hypothesized that single stranded oligonucleotides from microarrays could be used directly in the reaction without further amplification. To test whether unpurified oligo pools are compatible with NM, we synthesized a single custom oligonucleotide pool (Agilent technologies) comprising oligos encoding all missense and nonsense mutations from positions 1–69 of the bacterial aliphatic amidase AmiE (Wrenbeck et al. 2017, 1449 oligos of length 33–60 nts), all possible single nucleotide polymorphisms covering residues 15–114 for the anti-Influenza human antibody variable heavy gene UCA9 (Pappas et al. 2014, 1000 57-nt oligos corresponding to a total of 612 non-synonymous mutations), and targeted mutagenic oligos for the Arabidopsis thaliana abscisic acid receptor PYR1 (Park et al. 2015, 185 51-nt oligos printed with 6 replicates). Full oligo sequences are given in Supplementary Data 1.

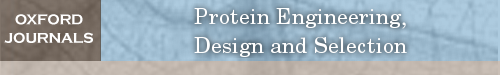

The lyophilized oligo pool was solubilized in 40 L TE at a total concentration of 200 nM, phosphorylated, and diluted directly so as to contain 1.9 nM AmiE-specific oligos. This dilution was used directly in a standard nicking saturation mutagenesis protocol with an amiE-encoding plasmid as a template (see Supporting Note 1). Two replicates were performed. We also performed a control reaction using degenerate ‘NNN’ oligos that were individually synthesized (IDT) covering the same stretch of the gene. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq in 250 bp paired end mode and processed using PACT (Klesmith and Hackel 2018). 100% (1380/1380) of the desired mutations were incorporated for each replicate (see Table I for full library statistics of all sequences; processed datasets are shown as heatmaps in Supplementary Figure S1). The frequency of specific mutants had a correlation of 0.88 between replicates, demonstrating the repeatability of the mutagenesis protocol (Fig S2a). Importantly, the oligo pool library had a much more even representation of all 20 amino acids compared with the degenerate oligos, with a mean coefficient of variation (CV) of 0.12 compared with 0.59, respectively (Fig 1a andFig S3). However, the cumulative distributions of libraries with respect to the number of counts—normalized to the average depth of coverage—were broadly similar (Fig 1b). To determine whether the melting temperature of an individual primer impacts its mutational efficiency, we analyzed the number of counts of a desired mutation as a function of the mutagenic primer melting temperature (Fig S4). We observed that higher primer melting temperatures correlate with higher observed mutational frequencies.

Table I.

Summary of statistics for single site saturation mutagenesis (SSM) and double site saturation mutagenesis (DSM) libraries.

| Oligo pool primers | Degenerate ‘NNN’ Oligos | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSM | DSM | SSM | ||||||

| AmiE Rep 1 (%) | AmiE Rep 2 (%) | PYR1 Rep 1 (%) | PYR1 Rep 2 (%) | UCA9 Rep 1 (%) | UCA9 Rep 2 (%) | PYR1 (%) | AmiE (%) | |

| Percentage of reads with: | ||||||||

| No nonsynonymous mutations: | 50.8 | 54.6 | 63.0 | 55.8 | 71.1 | 71.5 | 60.0 | 39.0 |

| One nonsynonymous mutation: | 38.0 | 34.9 | 24.1 | 29.0 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 32.0* | 48.0 |

| Multiple nonsynonymous mutations: | 11.2 | 10.5 | 11.8 | 15.2 | 15.5 | 14.6 | 9.0‡ | 13.0 |

| Coverage of all possible nonsynonymous amino acid mutations: | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 96.7 | 98 | 79.2* | 100 |

*One to two nonsynonymous mutations.

‡More than two nonsynonymous mutations.

Fig. 1.

A single unpurified oligo pool combined with nicking mutagenesis shows a near-complete coverage of all programmed mutations for user-defined single and double mutagenic libraries. (a) The relative amino acid substitution frequencies for AmiE libraries prepared using unpurified oligo pools and ‘NNN’ oligos (CV = coefficient of variation; rep = replicate). Relative frequencies were determined by dividing the sum of the total raw counts of a specific amino acid substitution by the average of all raw counts. (b) The cumulative distribution function of AmiE libraries as a function of the number of counts normalized to the average- depth of coverage. (c) Bar charts showing the percentage of total number of observed programmed versus non-programmed mutations for UCA9 libraries for the two different replicates. (d) A subset of the per position heatmap showing the number of counts per mutations encoded in PYR1 single site libraries. Boxes framed in red represent the programmed mutations. (e) Per position heatmaps comparing the unique expected versus observed programmed double mutations in the PYR1 double site mutagenic library. Boxes framed in orange represent the non-expected unique double mutations due to nucleotide mismatches between oligos and DNA template. (f) X-Gal staining of yeast colonies for PYR1 double mutants that interact with HAB1 in the presence of 1 μM Mandipropamid using an established yeast-two hybrid system. DMSO is the negative control.

To demonstrate that multiple libraries can be prepared from the same oligo pool, we sought to construct a library of all single nucleotide polymorphisms on the majority of UCA9 by performing NM with an UCA9-encoding plasmid as a template with the unamplified oligo pool. We observed a much wider range of variation per mutants compared to the AmiE libraries, which we speculate occurred because the oligos were diluted an additional 1000-fold. However, sequencing confirmed an average of 98% (594/612 and 606/612 nonsynonymous mutations from replicate 1 and replicate 2, respectively) of coverage of the desired mutations (Fig 1c, Fig S5) with a correlation of 0.99 and similar mutational frequencies between replicates (Fig S2b). Notably, mutations were specifically programmed, as there were on average only 5.8% (86/1 488) non-desired mutations observed in the read window (Fig 1c).

Oligo pools offer user-defined mutations relieved from the constraints of degenerate codon compatibility. We next sought to construct a library of 185 designed mutations at 17 positions in the PYR1 (Park et al. 2015) receptor by performing NM using the unamplified oligo pool with a PYR1-encoding plasmid as a template. All 185 mutations were encoded in the library (Fig 1d) and with a correlation of 0.93 between replicates (Fig S2c). Specifically programmed mutations were found on average at 91-fold higher frequencies than the other 1556 potential single non-synonymous mutations in the 261-nt Illumina sequencing window (median 1038 counts vs 0; mean 1198 counts vs. 13 for encoded vs. non-encoded positions) (Table I and Fig S6).

It is also possible to sequentially perform NM with the same oligo pool, creating mutagenic libraries with two mutations per gene. We tested this synthesis by performing NM again using the PYR1 single mutagenesis library plasmid DNA as a template. We expected 10 845 out of the 1 462,000 possible double point mutants in the Illumina sequencing read window. Deep sequencing recovered 13 904 double mutants with two or more read counts, of which 8 316 were specifically programmed (Fig 1e andFig S7). Double mutations were depleted at near-adjacent positions (Fig 1e), presumably because a second oligonucleotide containing mismatches would either not anneal or overwrite the mutation encoded from the first oligonucleotide. To demonstrate utility, this library was screened against the non-native ligand mandipropamid using a previously established yeast two hybrid screen (Park et al. 2015). We uncovered PYR1 mutants specific to and responsive at 1 μM mandipropamid; sequencing of 10 constructs showed all 10 had the same specifically programmed F108A F159M double mutant, which outcompeted single mutants F108A and F159M present in the library (Fig 1f).

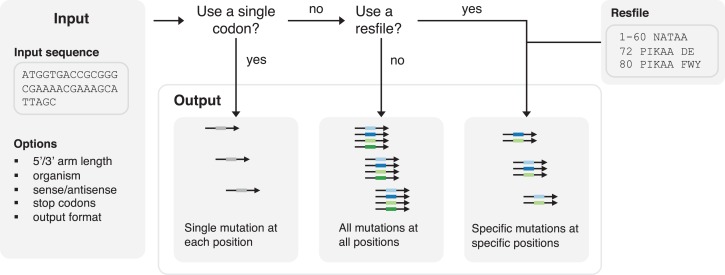

To automate the oligo pool design step, we provide a Python script. Given an input sequence, the script automatically designs oligo sequences and outputs them in a convenient format. It allows the user to set primer length and choose the number of different codons with which to encode each mutation. Codons are selected according to usage frequency in a user-specified organism. If a residue preference file (resfile) is provided, the script can provide oligos for user-specified mutations. For compatibility with synthesis of individual oligos, the user can provide a single degenerate codon to use for all mutagenic oligos. A decision tree and sample inputs for the software are shown in Fig 2. The script and documentation are provided in Supporting Information.

Fig. 2.

Automated oligo pool design for user-defined mutagenesis library construction. A decision tree and sample inputs for the PrimerDesignScript software.

In summary, we have shown that oligo pool synthesis technology can be integrated with nicking mutagenesis to construct user-defined single and double mutagenesis libraries. We anticipate its incorporation into standard directed evolution experiments and its utility for more thorough evaluation of local protein fitness landscapes.

Materials and methods

Strains. The Escherichia coli strain used in this study was XL1-Blue (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) endA1 supE44 thi-1 hsdR17 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F’ proAB lacIqZ∆M15 Tn10 (Tetr)]. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain used in this study was MaV99, MATa SPAL10::URA3.

Plasmid constructs. The pEDA3_amiE plasmid was created as described in Wrenbeck et al. 2016b. Plasmid pBD_PYR1_BbvCI was constructed from pBD_PYR1 (Park et al. 2015) by inserting a BbvCI restriction site using standard cloning. pETcon_UCA9 was created by inserting a codon-optimized VH gene encoding Met1—Ser122 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) into yeast display vector pETcon (Addgene plasmid #41 522) using standard restriction cloning. Sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ) and listed in Supporting Note 2.

Degenerate oligos and oligo pool design. All degenerate ‘NNN’ mutagenesis oligos were designed using Quick Change Primer Design Program (www.agilent.com) and were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies. A single 7 118-member oligonucleotide library pool was custom synthesized by Agilent Technologies (sequences listed in Supplementary Data 1).

Preparation of mutagenesis libraries. Single and double-site saturation mutagenesis libraries were constructed using nicking mutagenesis as described in Wrenbeck et al. 2016a, 2016b with the following changes. To conserve the 20:1 template to oligonucleotide ratio, the volume and concentration of oligos are determined using Supporting Note 1 for the AmiE and PYR1 libraries. The UCA9 libraries were prepared using an additional 1000:1 dilution of the oligo pool. The AmiE library covered residues Met1—Pro69, the PYR1 targeted library covered Val81—Arg167, and the UCA9 library covered Pro15—Gln114. For the PYR1 library encoding double mutants, we use the single-site mutagenesis PYR1 library as our dsDNA plasmid template. The expected number of double mutants was calculated based on the total number of non-synonymous mutations for each pair of desired positions.

Deep sequencing preparation and data analysis. The mutagenesis plasmids were prepared for deep sequencing exactly as described in Kowalsky et al. 2015, following ‘method B’. Then, libraries were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq using 2 × 250 bp pair-end reads by the BioFrontiers Sequencing Core at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Primers used for deep sequencing are listed in Table S1 and a summary of statistical results are in Table I. The software package PACT (Klesmith and Hackel 2018), freely available at GitHub (https://github.com/JKlesmith/PACT/), was used to calculate the sequencing counts obtained from raw FASTQ files. Raw sequencing reads for this work have been deposited in the SRA (SAMN10992661—SAMN10992668).

Yeast two-hybrid screening. The PYR1 double mutant library was transformed into yeast two-hybrid reporter strain MaV99 pACT-HABI and tested for responsiveness to 1 μM mandipropamid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as previously described by Park et al. 2015.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AI141452 to T.A.W. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by DARPA APT to T.A.W. and S.R.C., and NIH T32 Biotechnology Training Grant (Award # T32-GM110523) to A.M.C. This research was developed with funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The views, opinions and/or findings expressed are those of the author and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Data Availability

Raw sequencing reads have been deposited in the Sequencing Read Archive. All plasmids described in this work are available upon request. The oligo generation script is given as supplementary information.

Author contributions

Designed research: A.M.C., P.J.S., M.S.F., J.B., S.R.C., T.A.W.; performed research: A.M.C., P.J.S., M.S.F., M.B.K., A.N.B., J.B.; wrote the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors: A.M.C., P.J.S, T.A.W.

References

- Cozens C. and Pinheiro V.B. (2018) Nucleic Acids Res., 46, e51–e51. 10.1093/nar/gky067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firnberg E. and Ostermeier M. (2012) PLoS One, 7, e52031 10.1371/journal.pone.0052031 Jones, ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesmith J.R. and Hackel B.J., 2018. Improved mutant function prediction via PACT: Protein Analysis and Classifier Toolkit B. Berger, ed. Bioinformatics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kosuri S. and Church G.M. (2014) Nat. Methods, 11, 499–507. 10.1038/nmeth.2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalsky C.A., Klesmith J.R., Stapleton J.A., Kelly V., Reichkitzer N. and Whitehead T.A. (2015) PLoS One, 10, e0118193. G. Schreiber, ed.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas L., Foglierini M., Piccoli L. et al. (2014) Nature, 516, 418–422. 10.1038/nature13764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.-Y., Peterson F.C., Mosquna A., Yao J., Volkman B.F., Cutler S.R. et al. (2015) Nature, 520, 545–548. 10.1038/nature14123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plesa C., Sidore A.M., Lubock N.B., Zhang D., Kosuri S. et al. (2018) Science, 359, 343–347. 10.1126/science.aao5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrenbeck E. Klesmith,J.R., Stapleton, J.A. and Whitehead,T.A.. 2016. a. Protocol Exchange 10.1038/protex.2016.061 [DOI]

- Wrenbeck E.E., Azouz L.R. and Whitehead T.A. (2017) Nat. Commun., 8, 15695 10.1038/ncomms15695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrenbeck E.E., Klesmith J.R., Stapleton J.A., Adeniran A., Tyo K.E.J. and Whitehead T.A. (2016) Nat. Methods, 13, 928–930. 10.1038/nmeth.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequencing reads have been deposited in the Sequencing Read Archive. All plasmids described in this work are available upon request. The oligo generation script is given as supplementary information.