Abstract

Clearing agents (CAs) can rapidly remove non-localized targeting biomolecules from circulation for hepatic catabolism, thereby enhancing the therapeutic index (TI), especially for blood (marrow), of the subsequently administered radioisotope in any multi-step pretargeting strategy. Herein we describe the synthesis and in vivo evaluation of a fully synthetic glycodendrimer-based CA for DOTA-based pretargeted radioimmunotherapy (DOTA-PRIT). The novel dendron-CA consists of a non-radioactive yttrium-DOTA-Bn molecule attached via a linker to a glycodendron displaying sixteen terminal α-thio-N-acetylgalactosamine (α-SGalNAc) units (CCA α-16-DOTA-Y3+; molecular weight: 9059 Da). Pretargeting [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn with CCA α-16-DOTA-Y3+ to GPA33-expressing SW1222 human colorectal xenografts was highly effective, leading to absorbed doses of [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn for blood, tumor, liver, spleen, and kidneys of 11.7, 468, 9.97, 5.49, and 13.3 cGy/MBq, respectively. Tumor-to-normal tissues absorbed-dose ratios (i.e., TIs) ranged from 40 (e.g., for blood and kidney) to about 550 for stomach.

Keywords: Lu-177, pretargeted radioimmunotherapy, pretargeting, radioimmunotherapy, clearing agent, colorectal cancer

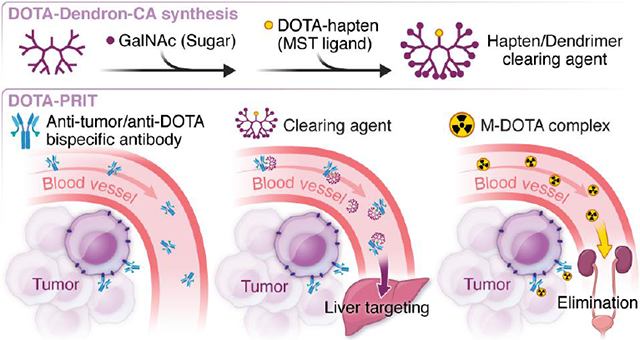

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The therapeutic indices (TIs; tumor-to-normal tissue-absorbed dose ratios) of radioimmunotherapy (RIT) should be maximized for safe and effective treatment of solid tumors.1 RIT with radiolabeled-IgG antibodies suffers from low TIs due to the unfavorable pharmacokinetics of the IgG carrier—slow localization in the targeted tumor and rapid, high uptake in the radiosensitive bone marrow and other reticuloendothelial tissues—and is thus often ineffective at maximum tolerated activities.1 We developed a S-2-(4-aminobenzyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane tetraacetic acid (DOTA) chelate-based pretargeting strategy (DOTA-PRIT) for theranostic imaging and treatment of solid tumors with DOTA-radiohaptens.2-5 DOTA-PRIT consists of separate, temporally spaced injections of three reagents: (1) a tetravalent bispecific IgG-single chain (IgG-scFv; 210 kDa) antibody (BsAb) with high affinity for (a) a tumor antigen (the IgG portion) and (b) the radiometal complex of S-2-(4-aminobenzyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane tetraacetic acid chelate ([M]-DOTA-Bn; the “C825” scFv portion)6; (2) a clearing agent (CA) to rapidly reduce circulating BsAb after sufficient time is given for BsAb to accumulate at antigen-positive tumor7; and (3) a radiolabeled DOTA-hapten such as the DOTA-Bn complex with the theranostic (i.e., gamma- and beta-emitting) isotope lutetium-177 ([177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn).8 To target the radioactivity to tumor, the low-molecular weight circulating DOTA-hapten rapidly enters the tumor parenchyma and binds to the intra-tumoral BsAb and is otherwise rapidly cleared via renal excretion.8 DOTA-PRIT has been applied to tumor antigens encompassing a wide variety of solid and hematological tumor types, targeting tumor antigens that include GD25, GPA332,3, HER24, CD209, CD3810, and CEA6.

For high-TI DOTA-PRIT, the CA step is interposed between injection of BsAb and radiolabeled DOTA-hapten.2-6, 9, 10 The currently utilized CA is a 500-kD dextran-DOTA hapten conjugate (dextran-CA) designed to bind to the anti-DOTA(M)-scFv domains of the BsAb in circulation via a DOTA(Y) moiety displayed on the dextran scaffold and remove it from the blood via recognition and catabolism by the reticuloendothelial system (RES).7 By virtue of its large size, undesirable binding of CA to tumor-associated BsAb is minimal because of its poor intra-tumoral extravasation.11 The use of dextran-CA for DOTA-PRIT and other pretargeting approaches (e.g., based on bioorthogonal inverse electron demand Diels–Alder reaction12) is facilitated by ease of synthesis and relatively low cost of starting materials as well as a favorable safety profile of dextran-conjugates in animals.

Although highly effective, the use of a dextran-CA has drawbacks. As a naturally occurring glucose polymer, the dextran scaffold is inherently polydisperse, thus presenting challenges related to reproducible batch-to-batch fabrication as well as in vivo use. Also, enzymatic degradation by RES dextran-1,6-glucosidase could potentially lead to the introduction of hapten fragments into the circulation, which will compete with the radiohapten itself for binding by tumor-BsAb.13 Similar issues applied to albumin-based CAs14,15 during clinical streptavidin-biotin PRIT, prompting the development of a dendrimer-based CA (dendron-CA) consisting of a biotin attached via a linker to a glycodendron displaying 16 terminal α-thio-N-acetylgalactosamine (α-SGalNAc) units for active hepatocyte targeting.16 The α-SGalNAc are ligands for the hepatocyte Ashwell-Morell receptor, a lectin involved in the recognition, binding, and clearance of asialoglycoproteins.17 This biotin-dendron-CA was shown to be effective and well-tolerated in patients (e.g., with no side effects during phase I/II studies of PRIT of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma18).

Herein, we sought to adapt the biotin-dendron-CA for DOTA-PRIT. We synthesized a novel DOTA-dendron-CA consisting of 16 terminal α-SGalNAc residues presented using a dendrimer core in place of the dextran and verified its effectiveness in vivo using model DOTA-PRIT.

Results and Discussion

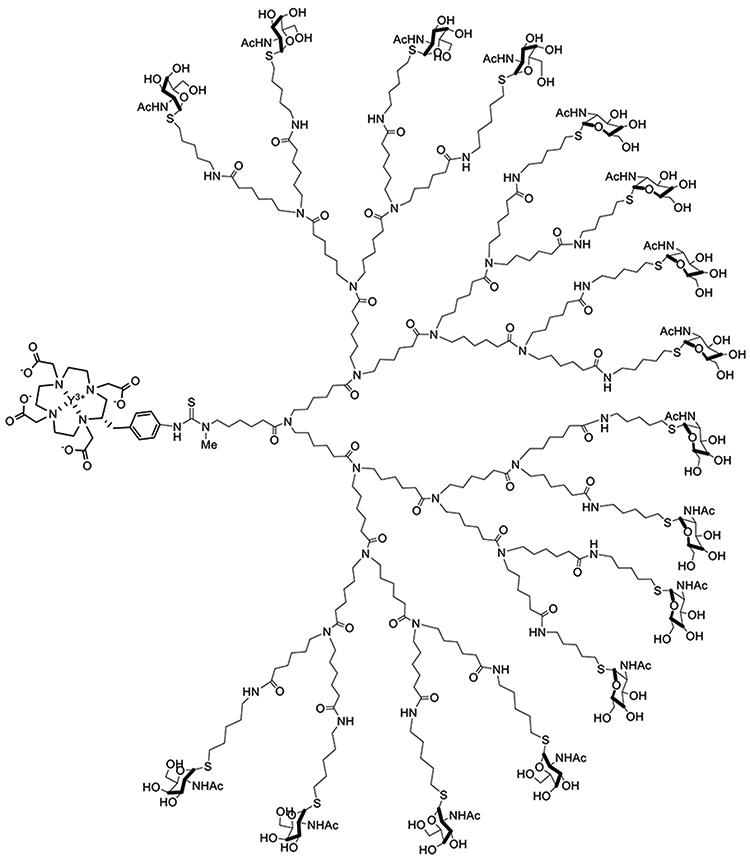

The dendron-CA (Figure 1; see SI for complete synthesis details) was prepared by mixing an advanced fourth-generation dendrimer intermediate, bearing 16 terminal α-SGalNAc residues and a free amine at the stem19, and commercially available S-2-(4-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane tetraacetic acid (p-SCN-Bn-DOTA) under basic conditions to provide the corresponding DOTA-thiourea-dendrimer.

Figure 1.

N-acetylgalactosamino dendron-clearing agent designed for use with DOTA-PRIT, CCA-16-DOTA-Y3+ dendron-CA.

For recognition and binding by the anti-DOTA antibody C825 (equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) = 15.4 ± 2.0 pM for Y-DOTA-Bn6, the DOTA-thiourea-dendrimer was loaded with yttrium using Y20 chloride hexahydrate under slightly acidic conditions. The final removal of all sugar acetate groups (48 of them) was performed under degassed conditions using 0.2 N NaOH in methanol. The dendron-CA CCA α-16-DOTA-Y3+ final product was purified by HPLC and fully characterized by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry to ensure product integrity and purity.

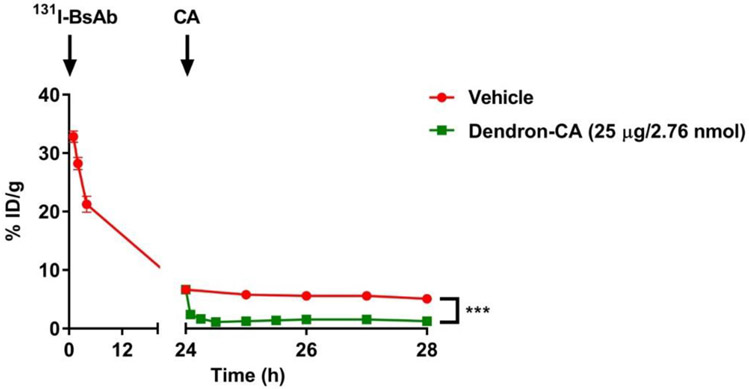

To verify the DOTA-dendron-CA’s effectiveness in vivo as well as to determine the kinetics of removal of DOTA-PRIT-BsAb from circulation, we initially conducted experiments in healthy (tumor-free) athymic nude mice using model radioiodinated-anti-GPA33/anti-DOTA huA33-C825 BsAb (131I-BsAb) as a tracer3. Initially, groups of animals (n = 3/group) were injected with 250 μg (1.19 nmol) of 131I-BsAb (19-22 μCi), a BsAb dose previously optimized for DOTA-PRIT.3 Twenty-four hours later, mice were injected with dendron-CA (25 μg, 2.76 nmol) or vehicle control. Serial tail-vein blood collection was performed at various times up to 4 hours post-injection of CA (or 28 hours post-injection of 131I-BsAb), and the 131I-activity concentration was determined by weighing each sample and radioassay in an 131I-calibrated gamma counter. As shown in below in Figure 2, there was initially no significant difference in blood 131I-activity at baseline (i.e., at 24 hours post-injection of the 131I-BsAb immediately prior to the injection of the CA) between groups, but the CA was very effective in decreasing circulating 131I-BsAb, as the average blood activity concentration significantly dropped by 64% at 5 minutes post-injection from 6.7 %ID/g at baseline to 2.4 %ID/g.

Figure 2.

Effect of dendron-CA CCA-16-DOTA-Y3+ on circulating 131I-BsAb in vivo. Athymic normal (tumor-free) mice were intravenously injected a t = 0 with 131I-BsAb (19-21 μCi; 250 μg, 1.19 nmol), followed with either vehicle (saline) or dendron-CA (25 μg; 2.76 nmol) at t = 24 hours. Serial blood sampling was conducted at various time points from t = 1-28 h post-injection of 131I-BsAb. Data is presented as mean ± SD. For some points, the error bars would be shorter than the height of the symbol. ***P <0.001 compared with vehicle.

At 1 hour post-injection of CA, the average blood activity was 1.3 %ID/g (−81% change from baseline) or 5.8 %ID/g (−13% change from baseline) in those mice given CA or vehicle, respectively. Typically, a 1- to 4-hour time interval between CA and hapten is used for DOTA-PRIT; the average blood activity at 4 hours was essentially unchanged from that at 1 h post-injection of CA (1.2 %ID/g, (−82% change from baseline) or 5.1 %ID/g (−13% change from baseline)) in those mice given CA or vehicle, respectively.

Next, we conducted CA dose-escalation studies using a model DOTA-PRIT system (targeting sub-cutaneous human colorectal cancer xenograft SW1222 in athymic nude mice with anti-GPA33-DOTA-PRIT) to evaluate the relationship between administered dendron-CA dose and subsequent uptake of [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn in tumor and normal tissues. Briefly, groups of SW1222 tumor-bearing mice (n = 3-4/group) were injected with BsAb (250 μg, 1.19 nmol; t = −28 hours) followed by varying amounts of CA (0-25 μg; 0-2.76 nmol; t = −4 hours). An additional group of tumored animals were given dextran-CA (62.5 μg; 0.125 nmol; 7.625 nmol (Y)DOTA) in place of the dendron-CA for comparison. Four hours after CA administration, the mice were injected with [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn (150-167 μCi; 30-33 pmol). Notably, we used a 24-hour time interval between BsAb and CA; we chose this time interval (e.g., to 48 hours) due to the reported limited serum stability of the C825 scFv; according to Orcutt, et al.21 the binding activity of the C825 scFv decreases to about 60% after 7 days in mouse serum at 37 degrees C. We intend to conduct further studies to clarify optimal timing, with the goal of achieving the highest possible therapeutic index, while maintaining sufficient tumor localization to achieve high tumor radiation-absorbed dose.

Based on previously published work, non-tumor-associated BsAbs-[177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn is metabolized in the liver and spleen, as evidenced by previous ex vivo serial biodistribution studies documenting relatively slow clearance of 177Lu-activity from those tissues in mice administered DOTA-PRIT plus [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn.3 As shown in Table 1, ex vivo biodistribution studies in groups of SW1222 tumor-bearing mice administered DOTA-PRIT plus [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn showed CA-dose dependent tumor-to-blood uptake (i.e., activity concentration) ratios of [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn at 24 hours post-injection of 177Lu-activity; e.g., average tumor-to-blood ratios were 2.9, 26, and 59 for vehicle (0 μg), 15 μg, or 20 μg of dendron-CA, respectively.

Table 1.

Dose escalation of dendron-CA during anti-GPA33 DOTA-PRIT + [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn. 177Lu-activity concentrations and corresponding tumor-to-blood ratios at 24 hours post-injection of [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn are shown. Please see SI Table 1 for additional data. Data is presented as mean ± SEM.

| Dose of CA | n | Blood (%ID/g) |

Tumor (%ID/g) |

Tumor/Blood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 μg vehicle | 4 | 11.9 ± 0.36 | 34.7 ± 4.04 | 2.9 ± 0.4 |

| 2.5 μg/0.276 nmol | 4 | 11.1 ± 1.15 | 32.5 ± 1.76 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

| 5 μg/0.552 nmol | 4 | 9.47 ± 0.28*** | 41.2 ± 3.55 | 4.4 ± 0.4 |

| 10 μg/1.10 nmol | 4 | 6.42 ± 1.25** | 31.5 ± 6.34 | 4.9 ± 1.4 |

| 15 μg/1.66 nmol | 4 | 1.27 ± 0.21*** | 33.3 ± 4.42 | 26.3 ± 5.5 |

| 20 μg/2.21 nmol | 4 | 0.46 ± 0.13*** | 27.2 ± 5.17 | 59.2 ± 20.0 |

| 25 μg/2.76 nmol | 3 | 0.40 ± 0.18*** | 30.8 ± 5.07 | 76.4 ± 36.2 |

| Dextran-CA 62.5 μg/0.125 nmol dextran/7.625 nmol (Y)DOTA | 4 | 0.45 ± 0.09*** | 34.6 ± 4.50 | 77.3 ± 19.2 |

P <0.001 compared with vehicle

P <0.01 compared with vehicle

P <0.05 compared with vehicle

A 25-μg dose of dendron-CA led an average tumor-to-blood uptake ratio of 76, almost identical to dextran-CA (average tumor-to-blood ratio of 77; see table S1). Furthermore, a 25-μg dose of dendron-CA resulted in low tissue uptake in other normal tissues, including liver and spleen. Notably, dosing from 5-25 μg with dendron-CA led to average tumor [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn uptakes of 27-41 %ID/g at 24 hours post-injection 177Lu-activity, with no statistical differences between vehicle (i.e., 0 μg of CA) and dextran-CA controls (each ~35 %ID/g). Furthermore, it was apparent that the dendron-CA did not have a negative impact on subsequent tumor uptake of [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn at doses ≤ 25 μg, as there were no statistical differences between vehicle and all studied doses of dendron-CA (2.5 – 25 μg). In data not shown, we found dendron-CA doses of 40-μg/mouse (n = 3), reduced uptake in tumor an average of 13.8 ± 1.16 %ID/g (significant P = 0.015 compared with 25-μg/mouse) with 0.28 ± 0.03 %ID/g and 0.67 ± 0.09 %ID/g for blood and kidney, respectively, at 24 hours post-injection 177Lu-activity (not significant P = 0.267 and P = 0.466, respectively, compared with 25-μg/mouse).

Lastly, using an optimized dendron-CA dose, serial biodistribution studies were performed to estimate absorbed doses and TIs during DOTA-PRIT with [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn. In order to calculate absorbed doses for PRIT plus [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn including dendron-CA, groups of nude mice bearing GPA33-expressing SW1222 xenografts (n = 5/group) was injected i.v. with the BsAb huA33-C825 (250 μg; 1.19 nmol) 28 h prior and i.v. with dendron-clearing agent CCA-16-DOTA-Y3+ (25 μg; 2.76 nmol) 4 h prior to administration of [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn (20 pmol, 3.7 MBq [100 μCi]). These mice were sacrificed at 1, 4, 24, or 48 h p.i. of [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn for biodistribution assay; dosimetry calculations were performed using the resulting organ time-activity data (Supplementary Information). The estimated absorbed doses (cGy/MBq) to tumor, blood, liver, and kidney for single-cycle PRIT plus dendron-CA were 468, 11.7 (TI: 40), 9.97 (TI: 47), and 13.3 (TI: 35), respectively (Table 2). In addition, absorbed doses were calculated for select tissues for DOTA-PRIT without dendron-CA by assuming that the respective areas under the curves (AUCs or residence times) and therefore the absorbed doses scaled as the 24-h %ID/g values (i.e., there was no difference in the 177Lu-activity kinetics with and without CA); the calculated estimated absorbed doses for tumor, blood, liver, and kidney were 593, 126 (TI: 4.7), 77 (TI: 7.7), and 39 (TI: 15), respectively.

Table 2.

Absorbed doses for pretargeting of [177Lu]LuDOTA-Bn anti-GPA33-DOTA-PRIT with dendron-clearing agent CCA-16-DOTA-Y3+ in nude mice carrying s.c. GPA33(+) SW1222 tumors. The therapeutic index (TI) is defined as estimated tumor/normal tissues absorbed dose ratio.

| Tissue | Absorbed dose (cGy/MBq) | Therapeutic index |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | 11.7 | 40 |

| Tumor | 468 | --- |

| Heart | 2.66 | 176 |

| Lung | 10.7 | 44 |

| Liver | 9.97 | 47 |

| Spleen | 5.49 | 85 |

| Stomach | 0.86 | 545 |

| Small Intestine | 1.16 | 404 |

| Large Intestine | 1.87 | 250 |

| Kidneys | 13.3 | 35 |

| Muscle | 3.73 | 126 |

| Bone | 3.68 | 127 |

Overall, the TIs ranged from about 40 (e.g., for blood and kidney) to about 550 for stomach. Previously with dextran-CA, we demonstrated effective treatment of SW1222 tumor-bearing mice (e.g., 111.0 MBq delivered in a fractionated dose strategy yielded a complete-response rate of 100%, including survival beyond 140 days post-tumor inoculation in two of nine mice) with estimated absorbed doses of 7304, 100, and 588 cGy to tumor, blood, and kidney and no demonstrable toxicity.3 Therefore, we anticipate that effective and safe colorectal cancer therapy in xenografts in mice is feasible with DOTA-PRIT plus dendron-CA, since a tumor-absorbed dose of ~73 Gy can be achieved with an administered activity of 15.6 MBq (with 183 cGy to blood (marrow) and 207 cGy to kidney, which are below benchmark maximum tolerated doses (MTDs) based on human normal-tissue radiation dose tolerance estimates derived from clinical observations of 250 cGy and 2,000 cGy for bone marrow and kidney, respectively.22 Furthermore, we estimate that the maximum tolerated pretargeted [177Lu] LuDOTA-Bn activity is 21 MBq, with the bone marrow as the dose-limiting organ. At this activity, the estimated absorbed dose delivered to tumor would be 9,828 cGy (98 Gy), with 246 cGy to blood (marrow) and 279 cGy to kidney.

Overall, these data suggest that this novel CCA-16-DOTA-Y3+ dendron-CA can be used in place of dextran-CA for enhanced blood clearance of a 131I-BsAb as well as for high-TI DOTA-PRIT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Tony Taldone for helpful comments. This study was supported in part by the Donna & Benjamin M. Rosen Chair (to S.M. Larson), Enid A. Haupt Chair (to N.K. Cheung), The Center for Targeted Radioimmunotherapy and Theranostics, Ludwig Center for Cancer Immunotherapy of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (to S.M. Larson), and Mr. William H. Goodwin and Mrs. Alice Goodwin and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research and The Experimental Therapeutics Center of MSK (to S.M. Larson). S.M. Larson was also supported in part by NIH grant P50 CA86438. The authors gratefully acknowledge the MSKCC Small Animal Imaging Core Facility, supported in part by NIH grant P30 CA008748. Work at the MSKCC Organic Synthesis Core is partially supported by NIH grant P01 129243. The authors would also like to thank the NIH (R01 233896, to S.M. Cheal).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting information is available free of charge.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

N.K. Cheung (NKC) reports receiving commercial research grants from Y-mAbs Therapeutics, Inc. and Abpro-Labs, Inc., holding ownership interest/equity in Y-mAbs Therapeutics and in Abpro-Labs, and owning stock options in Eureka Therapeutics, Inc. NKC is the inventor and owner of issued and pending patents, some licensed by MSK to Y-mAbs Therapeutics, Biotec Pharmacon, and Abpro Labs. NKC is a scientific advisory board member of Abpro Labs and Eureka Therapeutics. NKC, S.M. Larson, and S.M. Cheal were named as one of the inventors in the following patent applications relating to GPA33: SK2014-074, SK2015-091, SK2017-079, SK2018-045, SK2014-116, SK2016-052, and SK2018-068 filed by MSK. SML reports receiving commercial research grants from Genentech, Inc., WILEX AG, Telix Pharmaceuticals Limited, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; holding ownership interest/equity in Elucida Oncology Inc.; and holding stock in ImaginAb, Inc. SML is the inventor and owner of issued patents both currently unlicensed and licensed by MSK to Samus Therapeutics, Inc. and Elucida Oncology, Inc. SML is or has served as a consultant to Cynvec LLC, Eli Lilly & Co., Prescient Therapeutics Limited, Advanced Innovative Partners, LLC, Gerson Lehrman Group, Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. H. Xu, H. Guo, and O. Ouerfelli were also named as inventors on issued or pending patents filed by MSK.

References

- 1.Larson SM, Carrasquillo JA, Cheung NK, and Press OW (2015) Radioimmunotherapy of human tumours. Nat Rev Cancer 15, 347–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheal SM, Fung EK, Patel M, Xu H, Guo HF, Zanzonico PB, Monette S, Wittrup KD, Cheung NV, and Larson SM (2017) Curative multicycle radioimmunotherapy monitored by quantitative SPECT/CT-based theranostics, using bispecific antibody pretargeting strategy in colorectal cancer. J Nucl Med 58, 1735–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheal SM, Xu H, Guo HF, Lee SG, Punzalan B, Chalasani S, Fung EK, Jungbluth A, Zanzonico PB, Carrasquillo JA, et al. (2016) Theranostic pretargeted radioimmunotherapy of colorectal cancer xenografts in mice using picomolar affinity 86Y- or 177Lu-DOTA-Bn binding scFv C825/GPA33 IgG bispecific immunoconjugates. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 43, 925–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheal SM, Xu H, Guo HF, Patel M, Punzalan B, Fung EK, Lee SG, Bell M, Singh M, Jungbluth AA, et al. (2018) Theranostic pretargeted radioimmunotherapy of internalizing solid tumor antigens in human tumor xenografts in mice: Curative treatment of HER2-positive breast carcinoma. Theranostics 8, 5106–5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheal SM, Xu H, Guo HF, Zanzonico PB, Larson SM, and Cheung NK (2014) Preclinical evaluation of multistep targeting of diasialoganglioside GD2 using an IgG-scFv bispecific antibody with high affinity for GD2 and DOTA metal complex. Mol Cancer Ther 13, 1803–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orcutt KD, Slusarczyk AL, Cieslewicz M, Ruiz-Yi B, Bhushan KR, Frangioni JV, and Wittrup KD (2011) Engineering an antibody with picomolar affinity to DOTA chelates of multiple radionuclides for pretargeted radioimmunotherapy and imaging, Nucl Med Biol 38, 223–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orcutt KD, Rhoden JJ, Ruiz-Yi B, Frangioni JV, and Wittrup KD (2012) Effect of small-molecule-binding affinity on tumor uptake in vivo: a systematic study using a pretargeted bispecific antibody. Mol Cancer Ther 11, 1365–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orcutt KD, Nasr KA, Whitehead DG, Frangioni JV, and Wittrup KD (2011) Biodistribution and clearance of small molecule hapten chelates for pretargeted radioimmunotherapy. Mol Imaging Biol 13, 215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green DJ, Frayo SL, Lin Y, Hamlin DK, Fisher DR, Frost SH, Kenoyer AL, Hylarides MD, Gopal AK, Gooley TA, et al. (2016) Comparative analysis of bispecific antibody and streptavidin-targeted radioimmunotherapy for B-cell cancers. Cancer Res 76, 6669–6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green DJ, O’Steen S, Lin Y, Comstock ML, Kenoyer AL, Hamlin DK, Wilbur DS, Fisher DR, Nartea M, Hylarides MD, et al. (2018) CD38-bispecific antibody pretargeted radioimmunotherapy for multiple myeloma and other B-cell malignancies. Blood 131, 611–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt MM, and Wittrup KD (2009) A modeling analysis of the effects of molecular size and binding affinity on tumor targeting, Mol Cancer Ther 8, 2861–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer JP, Tully KM, Jackson J, Dilling TR, Reiner T, and Lewis JS (2018) Bioorthogonal masking of circulating antibody-TCO groups using tetrazine-functionalized dextran polymers. Bioconjug Chem 29, 538–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheal SM, Yoo B, Boughdad S, Punzalan B, Yang G, Dilhas A, Torchon G, Pu J, Axworthy DB, Zanzonico P, et al. (2014) Evaluation of glycodendron and synthetically modified dextran clearing agents for multistep targeting of radioisotopes for molecular imaging and radioimmunotherapy. Mol Pharm 11, 400–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knox SJ, Goris ML, Tempero M, Weiden PL, Gentner L, Breitz H, Adams GP, Axworthy D, Gaffigan S, Bryan K, et al. (2000) Phase II trial of yttrium-90-DOTA-biotin pretargeted by NR-LU-10 antibody/streptavidin in patients with metastatic colon cancer. Clin Cancer Research 6, 406–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breitz HB, Weiden PL, Beaumier PL, Axworthy DB, Seiler C, Su FM, Graves S, Bryan K, and Reno JM (2000) Clinical optimization of pretargeted radioimmunotherapy with antibody-streptavidin conjugate and 90Y-DOTA-biotin. J Nucl Med 41, 131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theodore LJ, and Axworthy DB, inventors. Cluster clearing agents, U.S. Patent 6 172 045 January 9, 2001.

- 17.Grewal PK (2010) The Ashwell-Morell receptor. Methods Enzymol 479, 223–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiden PL, Breitz HB, Press O, Appelbaum JW, Bryan JK, Gaffigan S, Stone D, Axworthy D, Fisher D, and Reno J (2000) Pretargeted radioimmunotherapy (PRIT) for treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL): initial phase I/II study results, Cancer Biother Radiopharm 15, 15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoo B, Cheal SM, Torchon G, Dilhas A, Yang G, Pu J, Punzalan B, Larson SM, and Ouerfelli O (2013) N-acetylgalactosamino dendrons as clearing agents to enhance liver targeting of model antibody-fusion protein, Bioconjug Chem 24, 2088–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen EE, Curry TS III, and Nunnally J (1973) An Introduction to the Physics of Diagnostic Radiology. Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia, PA: 252. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orcutt KD, Ackerman ME, Cieslewicz M, Quiroz E, Slusarczyk AL, Frangioni JV, Wittrup KD (2010) A modular IgG-scFv bispecific antibody topology. Protein Eng Des Sel 23, 221–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marks LB, Yorke ED, Jackson A, Ten Haken RK, Constine LS, Eisbruch A, Bentzen SM, Nam J, and Deasy JO (2010) Use of normal tissue complication probability models in the clinic. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 76, S10–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.