Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS:

Low rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance are primarily due to provider-related process failures. However, few studies have evaluated primary care provider (PCP) practice patterns, attitudes, and barriers to HCC surveillance at academic tertiary care referral centers.

METHODS:

We conducted a web-based survey of PCPs at 2 tertiary care referral centers (133 providers) from June 2017 through December 2017. The survey was adapted from pretested surveys and included questions about practice patterns, attitudes, and barriers to HCC surveillance. We used the Fisher exact and Mann–Whitney rank-sum tests to identify factors associated with adherence to HCC surveillance recommendations, for categoric and continuous variables, respectively.

RESULTS:

We obtained a provider-level response rate of 75% and clinic-level response rate of 100% (133 providers). Whereas most PCPs performed HCC surveillance themselves, one-third deferred surveillance to subspecialists and referred patients to a hepatology clinic. Providers believed the combination of ultrasound and a-fetoprotein analysis to be highly effective for early stage tumor detection and reported using the combination for assessment of most patients. However, PCPs were more likely to use computed tomography– or magnetic resonance imaging-based surveillance for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or decompensated cirrhosis. Most providers believed HCC surveillance to be efficacious for early tumor detection and increasing survival. However, they desired increased high-quality evidence to characterize screening benefits and harms. Providers expressed notable misconceptions about HCC surveillance, including the role for measurement of liver enzyme levels in HCC surveillance and cost effectiveness of surveillance in patients without cirrhosis. They also reported barriers, including not being up to date on HCC surveillance recommendations, limited time in the clinic, and competing clinical concerns.

CONCLUSIONS:

In a web-based survey, PCPs reported misconceptions and barriers to HCC surveillance. This indicates the need for interventions, including provider education, to improve HCC surveillance effectiveness in clinical practice.

Keywords: Liver Cancer, Early Detection, NASH, Survey, Screening

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Despite advances in the management of hepatitis C infection, HCC remains the fastest growing cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1,2 Tumor stage at diagnosis is the strongest indicator of prognosis and candidacy for curative treatment.3,4 To improve early detection of HCC in patients with cirrhosis, professional societies, including the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver, recommend HCC surveillance using ultrasound with or without α-fetoprotein (AFP) every 6 months.1,4,5

Despite these recommendations, surveillance utilization has been poor. A minority of patients with cirrhosis undergo any surveillance, with less than 5% undergoing guideline-concordant semiannual surveillance.6–8 Recent focus has shifted to explore reasons why adherence to surveillance recommendations remain suboptimal to inform future intervention strategies. Prior studies have suggested provider-related processes, including failure to recognize cirrhosis and lack of provider orders, contribute more to HCC surveillance underuse than patient-related processes, such as poor adherence.9 Although subspecialty care with a gastroenterologist or hepatologist increases the odds of HCC surveillance at least 2-fold,6–8,10,11 primary care provider (PCP) visits do not appear to increase HCC surveillance utilization similarly.8,12 However, most patients with cirrhosis are seen by PCPs, with only 20% to 50% seen by a gastroenterologist or hepatologist, depending on the practice setting.8,13 Therefore, it is critical to evaluate PCP attitudes and barriers to surveillance to identify high-yield intervention targets that can improve HCC surveillance rates.

Engaging PCPs in HCC surveillance begins with identification and exploration of provider-reported barriers to surveillance. PCPs at an urban safety-net health system, comprised largely of racial/ethnic minority and uninsured patients, had a lack of knowledge about surveillance guidelines, misunderstanding about efficacy of screening modalities, and cited patient financial concerns as obstacles to regular surveillance.14 A survey of North Carolina PCPs, more than 80% of whom were in private practice, similarly showed many were unaware of surveillance recommendations and most deferred surveillance to subspecialists.15 These findings are not unexpected because HCC surveillance is recommended by the AASLD and the European Association for the Study of the Liver, but not societies such as the US Preventive Services Task Force or the American College of Physicians. It also is unclear if these results can be generalizable to PCPs at university-affiliated academic medical centers, because patients at tertiary care referral centers are more likely to undergo HCC surveillance.7,8 A paucity of data exist regarding provider knowledge, attitudes, and barriers for HCC surveillance at large academic medical centers. The objective of this study was to investigate knowledge and barriers to HCC surveillance among PCPs at university-affiliated academic medical centers.

Methods

Participants

We included PCPs at 2 university-affiliated tertiary care referral medical centers: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UT Southwestern) and University of Michigan Medical Center. UT Southwestern comprises 65 providers across 5 primary care clinics in Dallas, TX, and the University of Michigan includes 68 providers across 4 primary care clinics in Ann Arbor, MI. We included any PCP (ie, general internal medicine or family practice provider), who saw at least 1 patient with cirrhosis annually. We excluded medical trainees including residents or fellows, retired physicians, and PCPs who indicated their primary responsibility was research, administration, or teaching. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at UT Southwestern and the University of Michigan.

Survey Information

An anonymous survey was distributed electronically to all eligible PCPs between June 2017 and December 2017. Providers who did not complete the survey initially were given up to 3 additional opportunities: 2 additional electronic reminders followed by a printed version of the survey delivered to the provider’s office mailbox.

Survey content was derived as previously described,14 with modifications of validated questions16–20 and new questions constructed from a previously proposed model of physician behavior14 that included elements of interest proven to be effective in colorectal cancer screening.21 The survey comprised 3 sequential sections: (1) surveillance practices, (2) surveillance beliefs, and (3) practice and provider characteristics. The first section requested information on the type of patients seen, patterns of surveillance modality, and interactions with patients regarding HCC surveillance in the clinic. The next section concentrated on provider attitudes about the efficacy of surveillance modalities, application of surveillance modalities in patient scenarios, and attitudes about HCC surveillance. The final section focused on provider education and practice and provider demographics. In total, the survey took approximately 20 minutes to complete. The full survey is included in Supplementary Figure 1.

Study Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

Our primary outcome of interest was provider-reported practice patterns and knowledge regarding HCC surveillance recommendations per the AASLD guidelines. This outcome was assessed in 2 independent manners. First, providers were asked to provide self-reported semiannual surveillance rates for patients with cirrhosis. Second, providers were given patient vignettes and asked if they would recommend HCC surveillance. Six cases justified HCC surveillance, and 2 cases did not warrant surveillance. These surveillance recommendations were categorized into 3 possibilities: overuse, underuse, and appropriate guideline-consistent use. Secondary outcomes of interests were surveillance test choice (ultrasound alone, AFP alone, ultrasound and AFP, computed tomography [CT] and/or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], or no surveillance) and surveillance interval (every 3 months, every 6 months, every 12 months, or other).

The Fisher exact test and the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test were performed to identify factors associated with guideline-consistent HCC surveillance recommendations for categoric and continuous variables, respectively. Independent variables included perceived test effectiveness and the influence of factors such as guidelines, practice patterns of colleagues, legal liability, and patient preferences. We assessed potential barriers to surveillance including difficulty in identifying patients with liver disease and/or cirrhosis, time constraints in the clinic, lack of patient interest, difficulty communicating with patients, poor patient compliance, and a shortage of facilities to provide HCC surveillance. Physician and practice demographics included age, sex, race and ethnicity, number of years in practice, provider type (MD vs Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine vs physician’s assistant/nurse practitioner), and number of patients seen during a typical week. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05. All data analysis was performed using Stata 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Practice and Provider Characteristics

We obtained a provider-level response rate of 75% and a clinic-level response rate of 100%. Provider characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The median age of providers was 41 years, 65% were female, and the cohort was racially diverse (58% non-Hispanic white, 30% Asian, 7% black, and 5% Hispanic). More than 80% of providers were board certified in internal medicine, and approximately 10% were board certified in family practice. More than 75% of the providers spent the majority of their time performing clinical activities, with a median clinical effort of 75% (interquartile range, 16%–85%). Most respondents routinely cared for patients with cirrhosis, with more than 40% seeing more than 10 cirrhosis patients annually.

Table 1.

Primary Care Provider Characteristics

| Characteristics | All providers (N = 100) | UT Southwestern (N = 55) | University of Michigan (N = 45) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% male) | 30 (34.9%) | 19 (35.9%) | 11 (33.3%) | .81 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 50 (58.1%) | 25 (47.2%) | 25 (75.8%) | .04 |

| Hispanic white | 4 (4.7%) | 3 (5.7%) | 1 (3.0%) | |

| Black | 6 (7.0%) | 6 (11.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Asian | 26 (30.2%) | 19 (35.9%) | 7 (21.2%) | |

| Medical specialty | ||||

| MD, internal medicine | 72 (83.7) | 40 (75.5) | 32 (97.0) | .02 |

| MD, family practice | 11 (12.8) | 11 (20.8) | 0(0) | |

| Advanced practice provider | 3 (3.5) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Years in practice | ||||

| <5 | 23 (27.4) | 15 (28.3) | 8 (25.8) | .47 |

| 5–9 | 13 (15.5) | 10 (18.9) | 3 (9.7) | |

| 10–14 | 12 (14.3) | 9 (17.0) | 3 (9.7) | |

| 15–19 | 7 (8.3) | 4 (7.6) | 3 (9.7) | |

| ≥20 | 29 (34.5) | 15 (28.3) | 14 (45.2) | |

| Time spent on clinical care | ||||

| 0–25 | 13 (15.1) | 7 (13.2) | 6 (18.2) | .11 |

| 25–49 | 4 (4.7) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (9.1) | |

| 50–74 | 24 (27.9) | 19 (35.9) | 5 (15.2) | |

| 75–100 | 45 (52.3) | 26 (49.1) | 19 (57.6) | |

| Cirrhosis patients per year, n | ||||

| 1–10 | 57 (57.6) | 36 (65.5) | 21 (47.7) | .11 |

| 11–25 | 32 (32.3) | 16 (29.1) | 16 (36.4) | |

| 26–50 | 7 (7.1) | 3 (5.4) | 4 (9.1) | |

| >50 | 3 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.8) |

UT Southwestern, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Fifty-five percent of respondents practiced at UT Southwestern Medical Center and 45% practiced at the University of Michigan. Most (>80%) providers were not aware of any clinic-based reminders for HCC surveillance, and 16% relied on verbal reminders from care team members during clinic visits. More than 60% of respondents reported that the majority of their patients were Caucasian, with fewer than 10% seeing more than 20% Hispanic or Asian patients and fewer than 25% of respondents seeing more than 20% black patients. Providers primarily reported seeing insured patients, with fewer than 5% of providers seeing more than 20% uninsured patients.

Provider Attitudes and Barriers to Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance

Provider-reported attitudes regarding HCC surveillance are reported in Table 2 and Figure 1. The large majority of providers reported that HCC surveillance is effective for early tumor detection (91.9%), for reducing overall mortality (81.4%), cost effective in cirrhosis (82.5%), and can pose a legal liability if not performed in at-risk patients (80.5%). However, more than 40% of providers incorrectly believed that HCC surveillance also is cost effective in patients without cirrhosis.

Table 2.

Primary Care Provider Attitudes Regarding HCC Surveillance in Patients With Cirrhosis

| Provider attitude | All providers (N = 100) | UT Southwestern (N = 55) | University of Michigan (N = 45) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC surveillance is effective for early tumor detection | ||||

| Strongly agree, n (%) | 29 (33.3) | 19 (35.9) | 10 (29.4) | .63 |

| Agree, n (%) | 51 (58.6) | 29 (54.7) | 22 (64.7) | |

| Disagree, n (%) | 7 (8.1) | 5 (9.4) | 2 (5.9) | |

| Strongly disagree | — | — | — | |

| HCC surveillance reduces all-cause mortality | ||||

| Strongly agree, n (%) | 21 (24.4) | 18 (34.0) | 3 (9.1) | .03 |

| Agree, n (%) | 49 (57.0) | 28 (52.8) | 21 (63.6) | |

| Disagree, n (%) | 15 (17.4) | 6 (11.3) | 9 (27.3) | |

| Strongly disagree, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.9) | — | |

| HCC surveillance is cost effective in patients with cirrhosis | ||||

| Strongly agree, n (%) | 26 (30.2) | 21 (39.6) | 5 (15.2) | .07 |

| Agree, n (%) | 45 (52.3) | 25 (47.2) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Disagree, n (%) | 14 (16.3) | 7 (13.2) | 7 (21.2) | |

| Strongly disagree, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | — | 1 (3.0) | |

| HCC surveillance is cost effective in patients without cirrhosis | ||||

| Strongly agree, n (%) | 7 (8.1) | 7 (13.2) | — | .005 |

| Agree, n (%) | 30 (34.5) | 23 (43.4) | 7 (20.6) | |

| Disagree, n (%) | 33 (37.9) | 14 (26.4) | 19 (55.9) | |

| Strongly disagree, n (%) | 17 (19.5) | 9 (17.0) | 8 (23.5) | |

| Not performing HCC surveillance poses malpractice liability | ||||

| Strongly agree, n (%) | 20 (23.0) | 16 (30.2) | 4 (11.8) | .09 |

| Agree, n (%) | 50 (57.5) | 30 (56.6) | 20 (58.8) | |

| Disagree, n (%) | 16 (18.4) | 7 (13.2) | 9 (26.5) | |

| Strongly disagree, n (%) | 1 (1.2) | — | 1 (2.9) | |

| More data quantifying HCC surveillance benefits are needed | ||||

| Strongly agree, n (%) | 24 (27.9) | 12 (22.6) | 12 (36.4) | .18 |

| Agree, n (%) | 42 (48.8) | 25 (47.2) | 17 (51.5) | |

| Disagree, n (%) | 17 (19.8) | 13 (24.5) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Strongly disagree, n (%) | 3 (3.5) | 3 (5.7) | — | |

| More data quantifying HCC surveillance harms are needed | ||||

| Strongly agree, n (%) | 23 (26.7) | 12 (22.6) | 11 (33.3) | .38 |

| Agree, n (%) | 47 (54.7) | 29 (54.7) | 18 (54.6) | |

| Disagree, n (%) | 13 (15.1) | 9 (17.0) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Strongly disagree, n (%) | 3 (3.5) | 3 (5.7) | — | |

| An RCT evaluating HCC surveillance is needed | ||||

| Strongly agree, n (%) | 12 (14.0) | 4 (7.6) | 8 (24.2) | .004 |

| Agree, n (%) | 43 (50.0) | 23 (43.4) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Disagree, n (%) | 22 (25.6) | 17 (32.1) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Strongly disagree, n (%) | 9 (10.5) | 9 (17.0) | — | |

| Education of PCPs about HCC surveillance is needed | ||||

| Strongly agree, n (%) | 37 (43.0) | 18 (34.0) | 19 (57.6) | .06 |

| Agree, n (%) | 46 (53.5) | 32 (60.4) | 14 (42.4) | |

| Disagree, n (%) | 3 (3.5) | 3 (5.7) | — | |

| Strongly disagree, n (%) | — | — | — |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PCP, primary care provider; RCT, randomized controlled trial; UT Southwestern, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

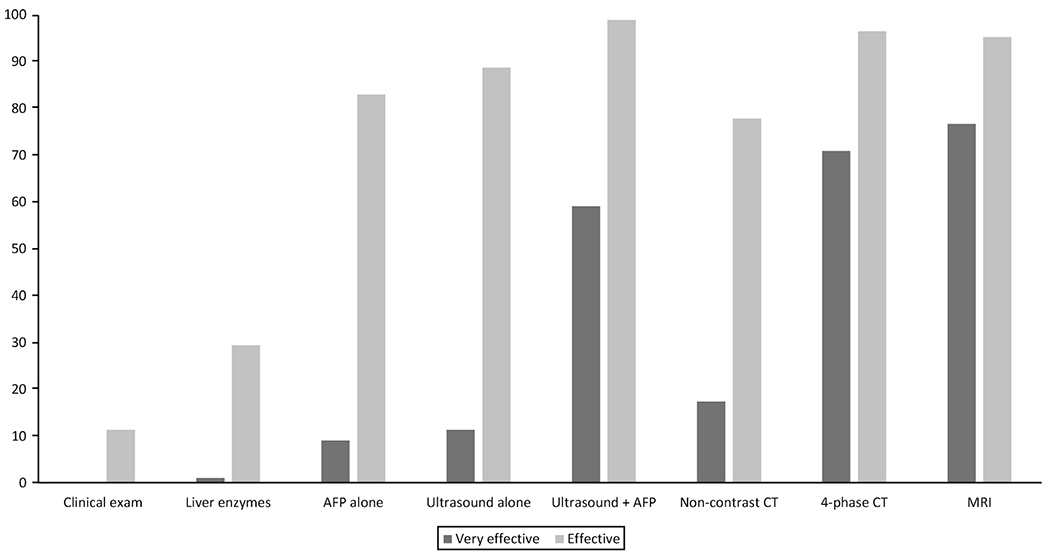

Figure 1.

Primary care provider perceptions of surveillance test effectiveness for early tumor detection.

Although only approximately 10% of providers strongly agreed ultrasound or AFP could be effective for early HCC detection if used alone, nearly 60% strongly agreed the combination of ultrasound with AFP could be effective. Similarly, more than 70% of providers strongly agreed CT and MRI could be effective for early tumor detection. However, some providers incorrectly believed clinical examination (11.4%) and monitoring liver enzyme levels (29.6%) could be effective for HCC surveillance.

More than 90% of providers believed professional society guidelines such as the AASLD and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network provide impetus to perform HCC surveillance. Of interest, 80.0% believed the lack of US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines did not deter the use of HCC surveillance. However, more than 75% of respondents believed further high-quality data quantifying screening-related benefits and harms are needed, including nearly two thirds of providers believing a randomized controlled trial should be performed. More than 40% of providers believed they were not up-to-date with HCC surveillance recommendations, and nearly all (96.5%) reported a need for increased PCP education about HCC and HCC surveillance.

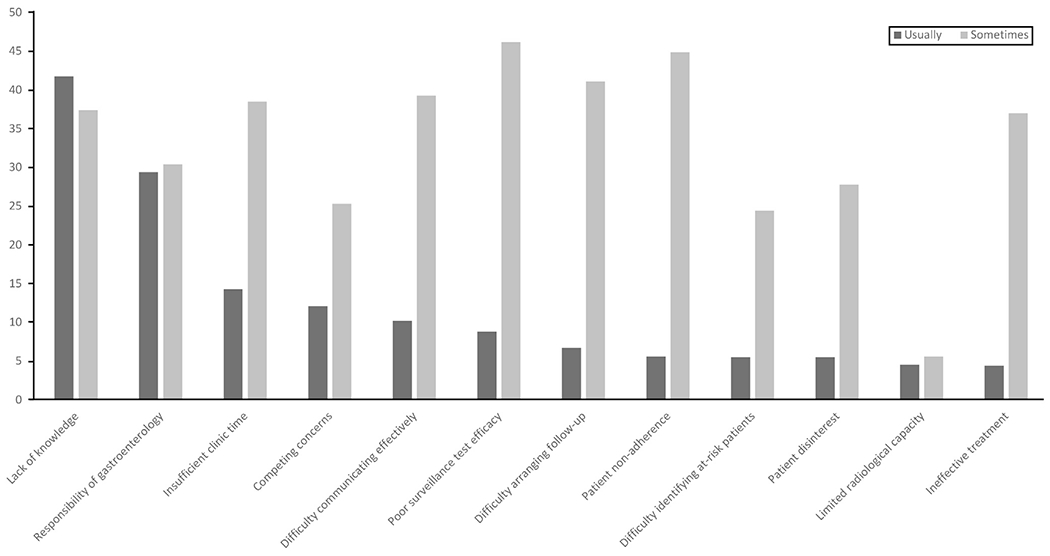

Barriers to HCC surveillance are detailed in Figure 2. The most commonly reported barriers were not being up-to-date with HCC surveillance recommendations (41.8%), considering HCC surveillance outside the scope of primary care (29.4%), limited time in the clinic (14.3%), having more important competing clinical concerns (12.1%), and difficulty communicating effectively with patients about HCC surveillance (10.2%). A higher proportion of PCPs at the University of Michigan considered HCC surveillance outside the scope of primary care (46.0 vs 18.2%; P = .01) and reported not being up-to-date with HCC surveillance recommendations (61.1% vs 29.1%; P = .005) than PCPs at UT Southwestern; however, other barriers were similar between the 2 sites. Less than 10% of providers reported barriers such as difficulty recognizing patients with cirrhosis, patients not adhering to surveillance orders, or a shortage of facilities for screening or diagnostic imaging.

Figure 2.

Primary care provider barriers to HCC surveillance.

Provider Surveillance Practices

Two thirds (67.0%) of providers reported ordering HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis, whereas one-third referred all cirrhosis patients for Hepatology care and deferred HCC surveillance to subspecialists. The proportion of providers who deferred HCC surveillance to subspecialists was higher at the University of Michigan (40.9% vs 26.4%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .13). The most commonly used surveillance tests at both sites were ultrasound with or without AFP, with 98.4% and 90.3% of PCPs who ordered HCC surveillance using ultrasound and AFP, respectively. However, nearly one third of providers who used ultrasound with or without AFP only did so annually. CT- and MRI-based surveillance were performed by only 7 (12.1%) and 5 (8.8%) providers, respectively, with no difference between the 2 sites (P = .70). The majority of providers reported no change in their use of ultrasound or AFP for HCC surveillance over the past year.

In clinical vignettes of patients with HCV or alcohol-related compensated cirrhosis, approximately 90% of providers reported performing surveillance using ultrasound with or without AFP. However, providers were significantly more likely to use CT-/MRI-based surveillance in patients with obesity/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) or decompensated cirrhosis than in patients with HCV or alcohol-related cirrhosis (16.1% and 19.5% vs 2.3% respectively; P < .001 for both). Providers were significantly less likely to order HCC surveillance in elderly patients, with more than one-third (36.8%) opting not to perform HCC surveillance in otherwise healthy 80-year-old patients with compensated cirrhosis. However, nearly three fourths (74.7%) of providers reported performing surveillance of patients with multiple comorbid conditions and two-thirds (62.1%) performed surveillance of patients with HCV infection in the absence of cirrhosis.

Discussion

This study assessed practice patterns, attitudes, and barriers to HCC surveillance among primary care providers at tertiary care academic referral centers. Although most PCPs performed HCC surveillance, one-third referred patients to the Hepatology Department and deferred surveillance to subspecialists. Providers believed HCC surveillance could be efficacious for early tumor detection and improving survival; however, they expressed some important misconceptions about HCC surveillance and reported barriers including limited time in the clinic and competing clinical concerns. Our study highlights the need for interventions including provider education to optimize HCC surveillance in clinical practice.

Providers believed HCC surveillance was beneficial in patients with cirrhosis; however, many expressed a desire for increased high-quality data characterizing both HCC surveillance benefits and harms. Although there are several cohort studies supporting HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis, most studies have notable limitations including lead time and length time bias, as well as the potential for confounders.22,23 There also are limited data evaluating physical, financial, and psychological harms of HCC surveillance.24,25 These data are particularly important in light of experiences in breast and prostate cancer screening, in which changes in screening recommendations as a result of evolving data on the risk-benefit ratio created patient and provider uncertainty and mistrust. A previously attempted randomized controlled trial in Australia was terminated given a lack of enrollment26; however, our data suggest providers in the United States now may be willing to enroll their patients in a randomized clinical trial.

Although HCC surveillance is recommended primarily by subspecialty and not primary care professional societies, we found most PCPs generally were knowledgeable about HCC surveillance. However, they expressed misconceptions, including more than one-fourth believing liver enzyme levels are helpful for HCC surveillance. This is concerning because patients with cirrhosis can have minimally increased, or even normal, liver enzyme levels, and false reassurance in these cases could lead to underuse of surveillance. Similarly, more than one third of providers withheld HCC surveillance from an otherwise healthy elderly patient, despite data showing similar benefits in well-selected elderly patients.27,28 Conversely, many providers believe surveillance is cost effective in patients without cirrhosis and many providers reported performing HCC surveillance in patients without cirrhosis or in those with multiple comorbid conditions. Overuse of surveillance in low-risk patients or in those with high competing risks of mortality would increase screening-related harms with little incremental benefit. Provider education to identify appropriate at-risk patients, minimizing both underuse and overuse of HCC surveillance, is critical to maximize surveillance value.

The most commonly used surveillance tests were ultrasound and AFP; however, PCPs were more likely to use CT- or MRI-based surveillance in patients with NASH or decompensated cirrhosis. Similar findings also were reported in a survey study among PCPs at a safety-net health system, in which CT/MRI was used by approximately one fifth of providers in these subgroups.14 These subgroups are at higher risk for ultrasound-based surveillance failure, but the cost effectiveness of alternative strategies, including CT- or MRI-based surveillance, has not been established.29–31 Identification of cost-effective strategies in these subgroups is particularly important because the epidemiology of HCC shifts from HCV-related to NASH cirrhosis.32

Provider-reported barriers to HCC surveillance in our study included limited time in the clinic, competing clinical concerns, and being out-of-date with surveillance guidelines. Providers in our study did not report cirrhosis identification as a barrier but this has been shown to be common in retrospective cohort studies.9 Although provider education is an important intervention, it likely would be insufficient in isolation. Preventive care, including cancer screening, typically is relegated to only 1 to 2 minutes of a clinic visit. System-level interventions, such as electronic health reminders, nurse-based protocols, and mailed outreach interventions, have been shown to increase HCC surveillance rates significantly compared with opportunistic visit-based surveillance.33–35 Other interventions such as audit-and-feedback, with or without financial incentives, also may be effective but have yet to be evaluated.

We acknowledge that our study had limitations. Our study was performed in 2 academic tertiary care health systems, with Hepatology specialty care and liver transplant availability, and may not be generalized to other practice settings. Further data are needed to see if similar results are found in other health systems, such as large community practices. Second, HCC surveillance rates were self-reported and may not reflect provider practices per chart review. Because the survey was anonymous, we could not assess actual provider surveillance rates. Third, survey studies inherently are limited by nonresponse bias, in which providers who perform surveillance are more likely to respond, and response bias, in which respondents report how they should practice instead of actual practices.

Overall, our study provides insights into primary care provider practice patterns, attitudes, and barriers regarding HCC surveillance at tertiary care academic centers with access to Hepatology specialty care and liver transplantation. Despite PCPs believing HCC surveillance can be effective and beneficial in patients with cirrhosis, they have misconceptions about how best to perform surveillance and report several barriers to implementation. These misconceptions and barriers might explain the gap between the efficacy of HCC surveillance and its effectiveness in clinical practice. Overall, these findings highlight the need for provider education and systems-level interventions to optimize HCC surveillance effectiveness in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

What You Need to Know.

Background

Although many patients with cirrhosis are followed up by primary care providers, there are few data characterizing primary care provider knowledge, attitudes, and barriers for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance.

Findings

Although many primary care providers performed HCC surveillance, one-third deferred surveillance to subspecialists and referred all cirrhosis patients to a Hepatology Clinic. More than 80% of providers believed HCC surveillance could be efficacious for early tumor detection and increasing survival. However, they expressed important misconceptions about HCC surveillance, including more than one-fourth believing liver enzymes are helpful for HCC surveillance, and reported barriers, including limited time in the clinic and competing clinical concerns.

Implications for patient care

Primary care provider education and systems-level interventions are needed to increase HCC surveillance utilization and optimize surveillance effectiveness in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was conducted with support from National Cancer Institute grants R01CA212008 and RO1 CA222900, and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas 150587. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- AFP

α-fetoprotein

- CT

computed tomography

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PCP

primary care provider

- UT Southwestern

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology at www.cghjournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.029.

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASLEORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1118–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2018;391:1301–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2018; 67:358–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singal AG, Tiro J, Li X, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance among patients with cirrhosis in a population-based integrated health care delivery system. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51:650–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singal AG, Yopp A, Skinner C, et al. Utilization of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance among American patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:861–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer LB, Kappelman MD, Sandler RS, et al. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in a Medicaid cirrhotic population. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:713–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singal AG, Yopp AC, Gupta S, et al. Failure rates in the hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance process. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:1124–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg DS, Taddei TH, Serper M, et al. Identifying barriers to hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in a national sample of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2017;65:864–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davila JA, Morgan RO, Richardson PA, et al. Use of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis in the united states. Hepatology 2010;52:132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg DS, Valderrama A, Kamalakar R, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance among cirrhotic patients with commercial health insurance. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016;50:258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanyal A, Poklepovic A, Moyneur E, et al. Population-based risk factors and resource utilization for HCC: US perspective. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:2183–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalton-Fitzgerald E, Tiro J, Kandunoori P, et al. Practice patterns and attitudes of primary care providers and barriers to surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:791–798.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGowan CE, Edwards TP, Luong MU, et al. Suboptimal surveillance for and knowledge of hepatocellular carcinoma among primary care providers. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13:799–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farvardin S, Patel J, Khambaty M, et al. Patient-reported barriers are associated with lower hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance rates in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2017; 65:875–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klabunde CN, Vernon SW, Nadel MR, et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Med Care 2005;43:939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klabunde CN, Jones E, Brown ML, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with double-contrast barium enema: a national survey of diagnostic radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002; 179:1419–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klabunde CN, Frame PS, Meadow A, et al. A national survey of primary care physicians’ colorectal cancer screening recommendations and practices. Prev Med 2003;36:352–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadel MR, Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, et al. A national survey of primary care physicians’ methods for screening for fecal occult blood. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yabroff KR, Klabunde CN, Yuan G, et al. Are physicians’ recommendations for colorectal cancer screening guidelineconsistent? J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kansagara D, Papak J, Pasha AS, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singal AG, Pillai A, Tiro J. Early detection, curative treatment, and survival rates for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014; 11:e1001624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atiq O, Tiro J, Yopp AC, et al. An assessment of benefits and harms of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2017;65:1196–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor EJ, Jones RL, Guthrie JA, et al. Modeling the benefits and harms of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: information to support informed choices. Hepatology 2017;66:1546–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poustchi H, Farrell GC, Strasser SI, et al. Feasibility of conducting a randomized control trial for liver cancer screening: is a randomized controlled trial for liver cancer screening feasible or still needed? Hepatology 2011;54:1998–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunot A, Le Sourd S, Pracht M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients: challenges and solutions. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2016;3:9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trevisani F, Cantarini MC, Labate AM, et al. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly italian patients with cirrhosis: effects on cancer staging and patient survival. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1470–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simmons O, Fetzer DT, Yokoo T, et al. Predictors of adequate ultrasound quality for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 45:169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tzartzeva K, Obi J, Rich NE, et al. Surveillance imaging and alpha fetoprotein for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1706–1718.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del Poggio P, Olmi S, Ciccarese F, et al. Factors that affect efficacy of ultrasound surveillance for early stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1927–1933.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pais R, Fartoux L, Goumard C, et al. Temporal trends, clinical patterns and outcomes of NAFLD-related HCC in patients undergoing liver resection over a 20-year period. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:856–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beste LA, Ioannou GN, Yang Y, et al. Improved surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma with a primary care-oriented clinical reminder. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singal AG, Tiro JA, Marrero JA, et al. Mailed outreach program increases ultrasound screening of patients with cirrhosis for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2017;152: 608–615.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nazareth S, Leembruggen N, Tuma R, et al. Nurse-led hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance clinic provides an effective method of monitoring patients with cirrhosis. Int J Nurs Pract 2016;22(Suppl 2):3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.