Abstract

Site-specific recombinases, such as Cre, are a widely used tool for genetic lineage tracing in the fields of developmental biology, neural science, stem cell biology, and regenerative medicine. However, nonspecific cell labeling by some genetic Cre tools remains a technical limitation of this recombination system, which has resulted in data misinterpretation and led to many controversies in the scientific community. In the past decade, to enhance the specificity and precision of genetic targeting, researchers have used two or more orthogonal recombinases simultaneously for labeling cell lineages. Here, we review the history of cell-tracing strategies and then elaborate on the working principle and application of a recently developed dual genetic lineage-tracing approach for cell fate studies. We place an emphasis on discussing the technical strengths and caveats of different methods, with the goal to develop more specific and efficient tracing technologies for cell fate mapping. Our review also provides several examples for how to use different types of DNA recombinase–mediated lineage-tracing strategies to improve the resolution of the cell fate mapping in order to probe and explore cell fate–related biological phenomena in the life sciences.

Keywords: development, gene mapping, gene expression, genetics, stem cell, Cre-loxP, Dre-rox, dual recombination, genetic recombination, lineage trace, site-specific DNA recombinase, cell fate mapping, organ regeneration, tissue regeneration, reporter gene

Introduction

In developmental and regeneration studies, different cell types and lineages have unique properties and functions for biological processes. In studies of organ regeneration and tissue regeneration, we should identify the key cell types and their ultimate fate in complex biological process, such as their number, location, cell behavior, gene profile, and function. For in vivo cell fate studies, genetic lineage tracing represents a powerful approach to track and understand one cell lineage without in vitro artificial manipulation. Based on genetic DNA recombination, genetic lineage tracing is a way of permanently and indelibly marking a cell and its descendants for as long as they live. Therefore, genetic fate mapping studies based on this technology have been widely used to understand cell fate and behaviors in multiple life science disciplines, such as development, tumor biology, neuroscience, and regenerative medicine (1–3).

Before the widespread use of the DNA site-specific recombination (SSR)2 system for genetic lineage tracing, multiple strategies have been developed for labeling cells and tracking their fates. Vital dye labeling was the first physical approach used for cell lineage tracing in the early 20th century. This method employed agar chips impregnated with vital dyes and lipid-soluble carbocyanine dyes, such as octadecyl (C18) indocarbocyanines and oxacarbocyanine, that were integrated into the plasma membrane (4) (Fig. 1A); substrate-activated horseradish peroxidase–conjugated lipid-soluble fluorescence (5, 6); or DNA/histone level labeling (7–9). When cells migrate and divide, the fate of their descendants can be tracked by cell labeling. Moreover, analysis of 14C incorporation by genomic DNA, which was used during the Cold War, introduced another way to predict cell turnover by analyzing the present 14C level in tissues and to estimate its age (10, 11).

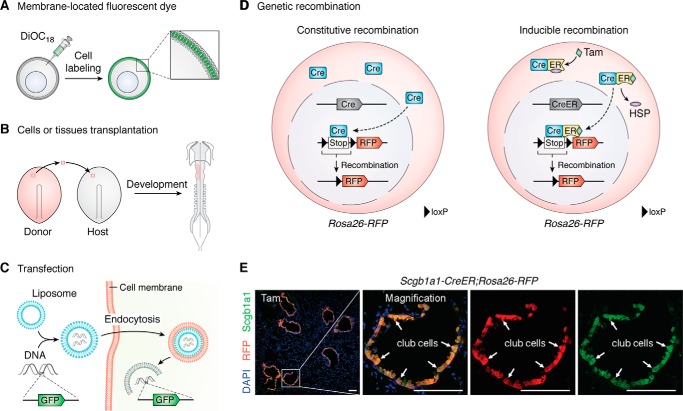

Figure 1.

Lineage-tracing strategies. A, dyes for cell labeling. The lipid-soluble carbocyanine dyes could be embedded into lipid bilayer for cell tracing. B, transplantation of labeled cells or tissues from donor embryo to host embryo. The fate of labeled cells or tissues could be tracked during embryonic development. C, introduction of reporter genes such as GFP by transfection or viral infection has been used for cell labeling. D, cell fate tracing by DNA site–specific recombination. The genetic recombination includes constitutive recombination and inducible recombination. Take the widely used Cre-loxP system as an example. The loxP-flanked transcriptional stop cassette (Stop) was inserted before the RFP gene. In constitutive recombination, after the cell type–specific promoter drives the Cre recombinase expression in target cells, the loxP-flanked Stop cassette can be removed, and the reporter gene would be turned on. Because the excision of genomic level is permanent and heritable, all Cre+ cells and their progeny could be labeled by the reporter gene. However, in inducible recombination, binding to heat shock proteins (HSPs), the Cre-ER fusion protein is held in the cytoplasm. Only after the ligand (tamoxifen) enters the cell cytoplasm and binds to ER can the Cre-ER fusion protein release from the HSP and enter the cell nucleus for Cre-loxP recombination. E, immunostaining for RFP, DAPI, and club cell marker Scgb1a1 on Scgb1a1-CreER;Rosa26-RFP adult lung section after tamoxifen treatment. White arrows, RFP+Scgb1a1+ club cells. Tam, tamoxifen. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Transplantation is another approach used in cell mapping studies (Fig. 1B). Transplantation of targeted cells or tissues from one embryo into another embryo has long been used for studying early embryonic development (12). More recently, transplantation has been widely used in stem cell fate studies of adult tissues, such as blood, skin, and tumors (13–16). Bone marrow transplantation is a classic approach for hematopoietic stem cell studies. Moreover, cancer cell transplantation has also been widely used in tumor biology research. However, cell fate plasticity results derived from cell transplantation may not be consistent with direct in vivo genetic fate tracing results and thus should be interpreted with caution (17). Transfection or viral infection is another useful approach for cell labeling that has been introduced since the end of the 20th century (Fig. 1C). The reporter genes encoding fluorescent protein or LacZ can be introduced in target cells by physical or chemical transfection or viral transduction for cell labeling and fate tracing (18–21).

The DNA SSR systems have been developed since the end of the 20th century (Fig. 1D). The SSR components include a recombinase enzyme and two recognition sites (1). Thus far, multiple DNA SSR systems have been identified for genomic engineering, such as Cre-loxP, FLP-FRT, Dre-rox, VCre-VloxP, SCre-SloxP, and Nigri-nox (22–26). Among all, the Cre-loxP system is the one most commonly used for mammalian gene editing. The widely used Cre-loxP site-specific recombination system of P1 bacteriophage contains two components, Cre (cyclization recombination) and loxP sites. Cre recombinase is a 38-kDa protein encoded by Cre cDNA, which could be driven by a specific promoter of a gene for user's interest. The loxP site is a 34-bp sequence, consisting of an 8-bp core region flanked by two 13-bp palindromic sequences (26). The Cre recombinase could recognize and catalyze the recombination between two loxP sites. The result of Cre-loxP recombination depends on the orientation of the two loxP sites. If their orientations are in the same direction, the Cre-loxP–mediated recombination results in the excision of the DNA sequence flanked by the two loxP sites. If their orientations are in opposite directions, the Cre-loxP–mediated recombination results in the inversion of the DNA sequences flanked by the two loxP sites. The Cre recombinase could specifically recognize loxP sites and efficiently mediate a Cre-loxP recombination event (26). Cre recombinase is driven by a cell- or tissue-specific promoter and another gene locus, generally a widely active one such as Rosa26, that harbors a loxP-flanked transcriptional stop cassette followed by a reporter gene. After Cre-loxP recombination, the stop cassette is removed, and the expression of the reporter gene is constitutively turned on. Because this genetic labeling is permanent and irreversible, the Cre-expressing cells and their progenies heritably express the reporter gene (26, 27). Such a genetic recombination technology has been widely applied in lineage-tracing and gene function studies in the fields of developmental biology, oncology, immunology, and stem cell and regeneration biology (1, 28–30).

According to the recombination type and readout, the genetic recombination systems could yield conventional single recombinase-mediated genetic readouts (conventional reporters) or more complex dual recombinase–mediated genetic readouts (dual reporters). Based on the number of fluorescent reporters that are needed for cell labeling, the conventional reporters could be further divided into single-color reporters and multicolor reporters. To facilitate tracing of the subpopulation of cells or to enhance the precision of lineage tracing, dual reporters are currently employed to reflect the varied combinatory readouts of dual recombinases. Based on the arrangement of the recognition sites and the readout, the dual genetic reporter systems could be categorized into three major types: intersectional reporters, exclusive reporters, and nested reporters. These categories will be explained in detail below along with examples that elucidate how dual lineage tracing can improve the resolution of cell fate mapping studies.

Conventional single recombinase–mediated genetic approach

For genetic lineage tracing, inducible Cre recombinase was developed with an attempt to achieve temporal and spatial control of recombination. To facilitate inducible recombination, the human estrogen receptor (ER) is fused to Cre recombinase. Because it binds to heat shock proteins (HSPs), the Cre-ER fusion protein is held in the cytoplasm. Upon induction by the ligand (tamoxifen or metabolite 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen) entering the cell cytoplasm and binding to the ER protein, the activated Cre-ER protein translocates into the nucleus and mediates Cre-loxP recombination (31). Given its ability for temporal control, this method has been widely applied in cell fate–tracing studies (Fig. 1D). Using the bronchiolar epithelial club cell maker gene Scgb1a1 (Secretoglobin1a1) as an example, Scgb1a1-CreER mouse was generated by inserting CreER sequences into the endogenous Scgb1a1 gene locus. The expression of CreER protein is thus specifically derived by Scgb1a1 gene promoter. After tamoxifen treatment in Scgb1a1-CreER;Rosa26-loxP-Stop-loxP-RFP double-positive mice, the CreER protein enters nucleus and mediates Cre-loxP recombination, removing the stop sequence and resulting in the RFP expression. We could detect that almost all Scgb1a1+ club cells are targeted by RFP. For example, using this tool, Hogan's group (32) demonstrated that the club cells of bronchioles could self-renew and regenerate ciliated cells after lung airway injury. The early reporter systems utilized a conventional strategy targeting single recombination. According to the number of fluorescent reporters that are needed for cell labeling, conventional reporter systems can be further divided into two categories: conventional single-color reporter systems and multicolor reporter systems (Fig. 2). The wide application of these strategies has greatly advanced multiple disciplines in the life sciences.

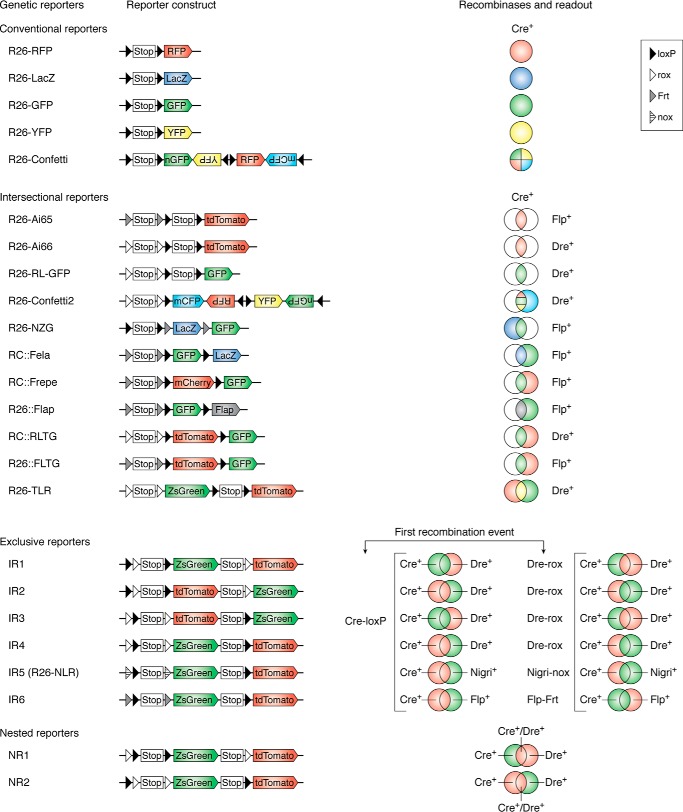

Figure 2.

Genetic recombination systems. The first column indicates different reporter alleles, the second and third columns show the reporter construct and recombinases, and the last column shows the readout of related reporter alleles. The conventional reporter system includes the single-color reporter system and the multicolor reporter system, which are derived by one type recombination. The novel dual-reporter systems include intersectional reporters, exclusive reporters, and nested reporters. In exclusive reporters, the readout depends on the first recombination type. For example, in IR1, the first Cre-loxP will remove the Stop cassette and a rox site, which labels the Cre+ cells (including both Cre+Dre− cells and Cre+Dre+ cells) as ZsGreen. The following Dre-rox recombination results in tdTomato expression of Dre+Cre− cells. In contrast, if the first recombination event is Dre-rox, the Dre+ cells (including both Dre+Cre− cells and Dre+Cre+ cells) are labeled as tdTomato, and the Dre−Cre+ cells would be labeled as ZsGreen by the following Cre-loxP recombination.

Conventional single-color reporter systems

Examples of the ubiquitous single-color reporter derived from a single recombination system include Rosa26-tdTomato, Rosa26-LacZ, Rosa26-GFP, and Rosa26-YFP (33–35) (Fig. 2). After recombination, the reporter gene labels promoter-activated cells for lineage tracing. By crossing Isl1-Cre with the CMV β-actin-nlacZ reporters, Sylvia Evans's group (36) identified IsL1 as a marker of the second heart field progenitors that contribute to the right ventricle, outflow tract, interventricular septum, and aria of the heart during early cardiac development. Hans Clevers's group (37) knocked EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 into the Lgr5 (leucine-rich-repeat-containing G protein–coupled receptor 5) locus and generated the Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 allele. EGFP represented the expression map of Lgr5-positive cells, and CreERT2 was used for lineage tracing. After crossing this allele with the Rosa26-lacZ reporter, they identified that Lgr5 was expressed in epithelial stem cells and that these Lgr5-positive stem cells could give rise to all epithelial cell lineages. Moreover, low doses of tamoxifen treatment can label cells at a single-cell level for clonal analysis. For example, Hopx+ early embryonic neural progenitors have been demonstrated to constantly contribute to dentate neurogenesis of the embryonic, postnatal, and adult stages by a clonal lineage-tracing study (38).

Conventional multicolor reporter systems

By designing different loxP sites and controlling their position/orientation, multicolor reporters have been used in the Cre-loxP system for single-cell labeling and clonal analysis, providing a valuable information on the fate of single cells after cell proliferation, differentiation. Several useful versions of “Brainbow” mouse lines have been available for clonal analysis of neurons, including Thy1-Brainbow-1.0, Thy1-Brainbow-1.1, Thy1-Brainbow-2.0, and Thy1-Brainbow-2.1 (39, 40). After recombination, the individual neurons were randomly labeled by a single-color reporter. More recently, another Rosa26-Confetti was generated by placing the construct under the control of Rosa26 locus, making construct expressed ubiquitously. Therefore, the new version of Rosa26-Confetti could be widely used in other stem cell research field. Using this reporter system, the Clevers group (40) randomly labeled the initial Lgr5+ stem cells and observed multicolor clones within the intestinal crypt. Over time, however, these Lgr5+ multicolor clones compete with each other, and finally, only a single fluorescent clone populates each crypt and contributes to the villi (40).

Mosaic analysis with double markers (MADM) is another Cre-dependent dual-color labeling system. One allele encodes the fluorescent proteins of the N terminus of RFP and the C terminus of GFP, which are separated by a loxP site. Another allele encodes the other halves of the fluorescent proteins of the N terminus of GFP and the C terminus of RFP, which are also separated by a loxP site. Only during cell mitosis do recombination events occur between these two loxP sites, resulting in activated full-length RFP and GFP reporters, followed by random labeling of daughter cells with red, green, or yellow fluorescence for lineage-tracing studies. The MADM system has been used for fate mapping of granular cells in the cerebellar cortex, revealing the tumor cell of origin in glioma (10, 41). An advantage of MADM is the accurate genetic readout of cytokinesis, which is very helpful in studying cardiomyocyte proliferation or division (42), due to the involvement of multinuclei and polyploidy during the progression of cell cycle. However, the low efficiency of interchromosome recombination prevents its capture of the majority of cells for analysis (43).

Despite the advances in technology that have generated these valuable tools, conventional strategies have some limitations that need to be considered. For instance, Cre recombinase is generally driven by a gene that is specifically expressed in a certain cell type. However, expression of certain genes that denote cell populations is not always specific. The gene that drives Cre could be ectopically or unintentionally activated in unwanted cell populations, thus leading to unwanted cell labeling (44). Additionally, a single recombinase could only target one cell population at a time, limiting its simultaneous detection in multiple cell lineages of one tissue. Detection of multiple cell lineages and tracing of their cell fate commitment during biological processes require a combination of orthogonal recombinases.

Multiple recombinase–mediated genetic fate mapping

If there are no genes unique to a specific cell type, it cannot be specifically labeled by the conventional approach. Moreover, targeting two gene promoters in one cell population could be more precise than relying on a single promoter as commonly employed in the conventional reporter system. Controlling the restrained reporter expression driven by two promoters requires two distinct SSRs. Recently, diverse dual recombinase–mediated genetic labeling systems have been developed to enhance the specificity and the number of cell types being labeled simultaneously. Cre-loxP, Flp-frt, Dre-rox, and Nigri-nox have been respectively used for designing dual systems (44). Given that the way in which multiple recombinases are used for resolving scientific questions largely relies on the readout of the reporter system, we use the reporter as an entry site to categorize these systems into three different types for multiple recombinase–mediated fate mapping studies, including intersectional reporters, exclusive reporters, and nested reporters (44, 45) (Fig. 2). Their working principles and examples of their application are discussed in the subsequent sections.

Intersectional reporters

The intersectional reporters usually respond to two sets of orthogonal recombination systems, and the expression of the reporters reflects different types of recombinase-mediated recombination (44, 45). The intersectional approach is suitable for genetic targeting of these cell types, which are generally defined by the expression of distinct genes. Based on reporter readout colors, the intersectional reporters could be further categorized into two subclasses: single-color reporter systems and multicolor reporter systems.

Single-color reporter systems

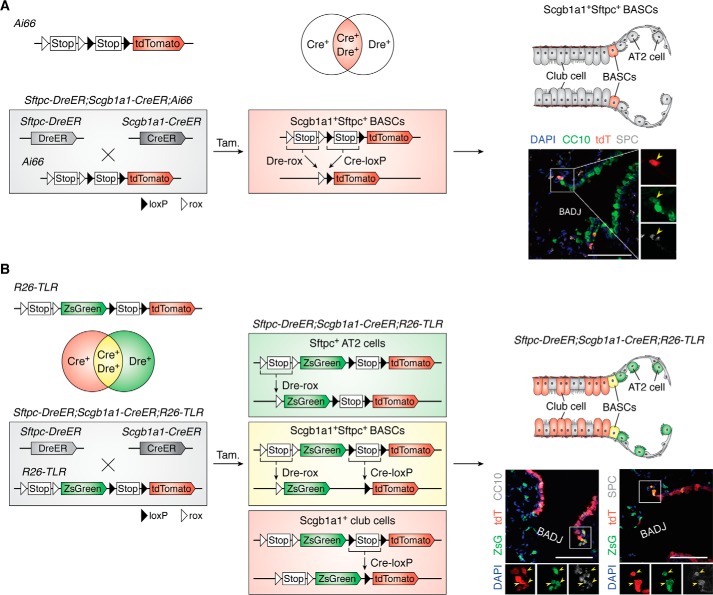

To precisely label one cell population, two cell-specific markers are sometimes used to define a cell population. The double marker–positive cell populations can be specifically labeled by a single reporter after dual recombination has completed in the intersectional single-color reporter systems (Fig. 2). For example, the Ai66 (Rosa26-CAG-rox-Stop-rox-loxP-Stop-loxP-tdTomato) system can be used for labeling double marker–positive cell populations (46–48). Here, we provide one example to delineate how this single-color reporter could be utilized for tracing one cell population defined by two marker genes. In the lung, various resident stem cell populations are distributed among the respiratory tract epithelium from proximal to distal, including the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli. Recent reports have identified a group of multipotent stem cells termed as bronchioalveolar stem cells (BASCs) located at bronchioalveolar duct junctions, which coexpress the bronchiolar club cell marker Scgb1a1 (also called CC10) and the alveolar type 2 cell marker Sftpc (49, 50). Ex vivo organoid culture of sorted Scgb1a1+Sftpc+ BASCs has shown multipotency after their differentiation into both bronchiolar and alveolar epithelial cells (50, 51). Nevertheless, the singular Sftpc-CreER tool could not specifically label BASCs (32). The lack of the single best marker gene specifically defining BASCs makes it impossible to determine its stemness using the conventional Cre-loxP–mediated lineage-tracing approach. Indeed, by using the intersectional genetic reporter system Ai66, Liu et al. circumvented this weakness and specifically traced Scgb1a1+ Sftpc+ BASCs through dual recombinases driven by two marker genes (47). In the Sftpc-DreER;Scgb1a1-CreER;Ai66 triple-positive mouse, the tdTomato reporter gene of Ai66 was activated in BASCs after double Dre-rox and Cre-loxP recombinations, which were driven by the Sftpc and Scgb1a1 promoters, respectively (Fig. 3A). By fate-mapping analysis, Liu et al. provided direct in vivo genetic evidence that BASCs at the bronchioalveolar duct junction have multipotency, generating multiple types of epithelial cells in bronchioles and alveoli after injuries (47). The double-positive cell types could also be labeled by other dual systems. For example, the “split-Cre” system is another novel technique for precisely targeting cell subpopulations when two marker genes are required to define one cell population. The N terminus of the Cre component and the C terminus of the Cre component are controlled by two distinct promoters. Only if the two promoters are both active in the same cell does the recombined functional Cre protein work for genetic labeling of the targeted cells (52). By using Scgb1a1-NCre and Sftpc-CCre mice, Thomas Braun's group (53) also proved that Scgb1a1+Sftpc+ BASCs actively participate in the regeneration of distal lung epithelia in vivo. For specifically targeting cell populations defined by two markers, both the double Dre-rox/Cre-loxP system and split-Cre system can be used to achieve it by combining with appropriate reporter systems. Differently, the mouse tools of the split-Cre system can only serve for this double-positive cell-labeling purpose, as NCre or CCre mouse tools do not work separately. However, the mouse tools of the double Dre-rox/Cre-loxP system also can used individually for conventional lineage tracing. Furthermore, combined with different dual-reporter systems (i.e. intersectional reporters, exclusive reporters, and nested reporters), the Cre- and Dre-expressing tools could be used for many different types of genetic cell labeling, such as Cre+Dre− or Cre−Dre+.

Figure 3.

Intersectional reporter systems. A, after dual Dre-rox and Cre-loxP recombination, the intersectional Ai66 reporter can specifically mark the Dre+Cre+ cells as tdTomato. In Sftpc-DreER;Scgb1a1-CreER;Ai66 triple-positive mouse, the Sftpc+Scgb1a1+ BASCs are labeled by tdTomato after tamoxifen treatment. The cartoon image (right) shows that BASCs are marked by red in the Sftpc-DreER;Scgb1a1-CreER;Ai66 triple-positive mouse. Yellow arrowheads in the sectional staining picture (right) indicate Sftpc+Scgb1a1+tdTomato+ BASCs. B, the R26-TLR is another intersectional system that could be used for tracing three cell populations simultaneously. Also, taking the lung epithelium as an example, in the Sftpc-DreER;Scgb1a1-CreER;R26-TLR triple-positive mouse, after Dre-rox recombination, the Sftpc+ AT2 cells are labeled as ZsGreen; after Cre-loxP recombination, the Scgb1a1+ are club cells labeled as tdTomato; and after both Dre-rox and Cre-loxP recombination, the Sftpc+Scgb1a1+ BASCs are labeled as ZsGreen and tdTomato, the readout for which is a yellow fluorescent color. A cartoon image (right) shows the club cells, AT2 cells, and BASCs marked as red, green, and yellow, respectively. Yellow arrowheads in the sectional staining picture (right) indicate ZsGreen+tdTomato+ BASCs. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Multicolor reporter systems

To facilitate genetic labeling of multiple cell types (the cell population and its subpopulation) at the same time with the use of additional colors, some intersectional genetic reporter systems incorporated two or more reporter genes (Fig. 2) (e.g. RC::Fela, RC::Frepe, R26-NZG, R26::Flap, R26-TLR, and Rosa26-Confetti2) (47, 54–59). The structure of some intersectional multicolor reporter systems can be summarized as a Promoter-site1-Stop-site1-site2-reporter A-Stop-site2-reporter B, including RC::Fela, R26-NZG, RC::Frepe, or R26::Flap (Fig. 2). In this design, expression of reporter A requires recombination of recombinase1-site1, and that of reporter B occurs only after recombinations of both recombinase1-site1 and recombinase2-site2. Therefore, this strategy can be used for consecutively labeling recombinase1+ cell populations by reporter A as well as their intersectional recombinase1+recombinase2+ subpopulations by reporter B. Furthermore, in R26-TLR, the structure is CAG promoter-site1-Stop-site1-reporter A-CAG promoter-site2-Stop-site2-reporter B (57). The expression levels of reporter A and reporter B are driven independently by two recombination events, which do not interfere with the readouts with each other. Therefore, the R26-TLR tool can be used to label three cell populations: A+B−, A+B+, and A−B+. Using lung epithelium as an example, Liu et al. (57) showed that the Sftpc-DreER;Scgb1a1-CreER;R26-TLR triple-positive lines could simultaneously trace the three cell populations of Sftpc+ AT2 cells, Scgb1a1+ club cells, and Sftpc+Scgb1a1+ BASCs at homeostasis and after injury (Fig. 3B). In addition to R26-TLR, Rosa26-Confetti2 is the improved version of the conventional R26-Confetti line. After recombination of both Dre-rox and Cre-loxP, the Dre+Cre+ cells and their progenies can be randomly labeled as RFP, YFP, or GFP (47, 58) (Fig. 2). Therefore, this new version of R26-Confetti2 is valuable for clonal analysis of cells defined by two marker genes. Using this tool, Han et al. (58) showed that a single SOX9+ hepatocyte has biopotency, giving rise to both hepatocytes and ductal cells after liver injury, and Liu et al. (60) reported that a single BASC has bidirectional potential to contribute to both bronchiolar and alveolar epithelial cells after lung injury. These examples illustrated how dual reporters can improve the resolution of cell fate mapping, enhancing our understanding of the fate plasticity of those unique cell populations that are not easily defined by tracing based on a single marker gene.

Exclusive reporters

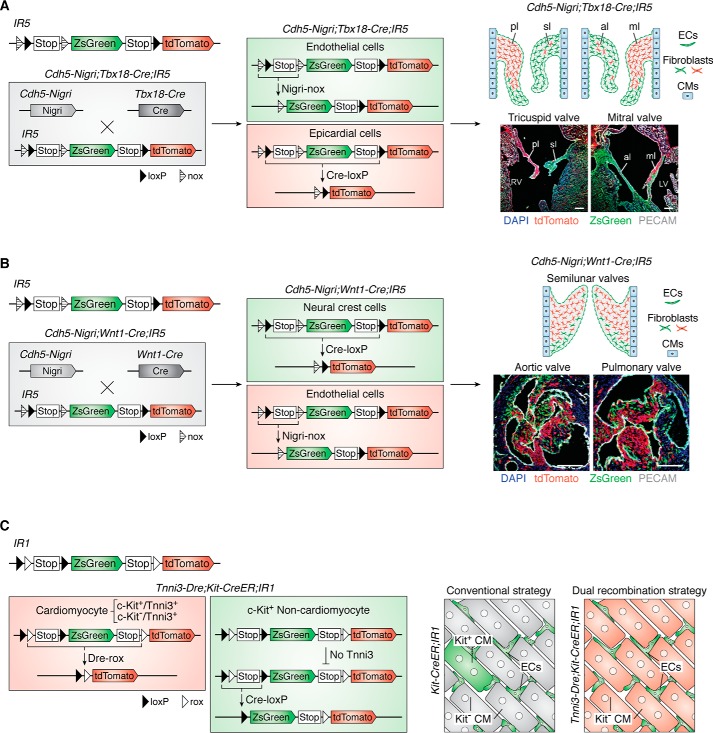

Usually, the activation of a gene in a cell type is not an “all” or “nothing.” A specific gene marker means that the activity of the promoter is relatively high in this cell type, which can be easily tested at transcription and protein levels. Sometimes the promoter of interest could be weakly activated in other cell types, which is regarded as ectopic expression. This ectopic expression can sometimes lead to genetic labeling, which is regarded as unwanted or unintentional tracing that may lead to some controversies regarding cell fate. Taking the c-kit gene as an example, by using the c-kit-CreER tool, previous studies reported that the c-kit+ cells are cardiomyocyte progenitors and could contribute to new cardiomyocytes after heart injury (61). However, subsequent study showed that the c-kit gene is also expressed in very few cardiomyocytes, indicating that traced cardiomyocytes after heart injury could be c-kit+ cardiomyocytes labeled previously. Some of the ectopic expression of genes could be detected at the protein level or transcription level, which is associated with the strength of promoter activity (45, 62). In this case, the exclusive reporter system is a better choice for specifically targeting a unique cell population through two recombination systems. Interleaved reporter 1 (IR1), IR2, IR3, IR4, and IR5 (R26-NLR) are exclusive reporters (24, 45). The structure of the exclusive reporter system is Promoter-site1-site2-Stop-site1-reporter A-Stop-site2-reporter B. These two pairs of recognition sites are interleaved distributed at the interleaving Rosa26 locus. If one recombination occurs first, the expression of the corresponding reporter gene would remove one recognition site of another recombination system. In other words, this would prevent a second recombination in the same cell type. Using IR1 as an example, the structure of IR1 is CAG-loxP-rox-Stop-loxP-ZsGreen-Stop-rox-tdTomato, and the first Cre-loxP recombination would result in ZsGreen expression that removes a rox site, preventing the subsequent Dre-rox recombination in the same cell (45). This strategy is applicable for specific labeling of targeted cells by circumventing ectopic labeling issues and for labeling two distinct cell populations simultaneously. Here, we use the controversial studies of putative c-kit+ cardiomyocyte progenitors as an example. Because some research groups showed that the c-kit is also expressed in very few cardiomyocytes, the controversy is that the newly generated cardiomyocytes are derived from c-kit+ cells or previously labeled c-kit+ cardiomyocytes. So only specifically targeted c-kit+ noncardiomyocytes can draw correct conclusions. The c-kit+ cardiomyocyte labeling cannot be excluded by conventional systems (Fig. 4C). But this controversy have been solved by incorporating the IR1 system and another cardiomyocyte-specific labeling tool, Tnni3-Dre. First, all Tnni3+ cardiomyocytes (including these unwanted c-kit+Tnni3+ cardiomyocytes) can be specifically labeled by Dre-rox recombination. Then after tamoxifen induction, c-kit-CreER could specifically label all c-kit+ cells (excluding these unwanted c-kit+Tnni3+ cardiomyocytes) (Fig. 4C). Fate-mapping analysis showed that c-kit+ noncardiomyocytes do not contribute to new cardiomyocytes at homeostasis or after injury (45). Another example is cardiac valve development. It has been reported that the atrioventricular valve mesenchyme is mainly derived from the epicardium and endocardium (63–65), and the aortic and pulmonary valve mesenchyme is primarily derived from cardiac neural crest cells and the endocardium (63, 66, 67). However, because of separate analyses performed using different lineage-tracing lines, there is still a lack of precise description in the diverse origins of valve mesenchyme of the same mouse heart during development. Liu et al. (24) reported an exclusive reporter system, IR5 (also named R26-NLR), which incorporates Cre-loxP and a newly identified Nigri-nox system. This reporter line can be used to simultaneously label two distinct progenitor cell populations and to identify the dynamic mesenchymal cell contribution from diverse sources during cardiac valve development. In the Tbx18-Cre;Cdh5-Nigri;IR5 triple-positive mouse line, the epicardial cell lineage was traced by tdTomato after Cre-loxP recombination, and the endocardial cell lineage was traced by ZsGreen after Nigri-nox recombination (Fig. 4A). Similarly, in the Wnt1-Cre;Cdh5-Nigri;IR5 triple-positive line, the neural crest lineage and endocardium lineage were traced by tdTomato and ZsGreen, respectively (Fig. 4B). By using IR5, they revealed that the mesenchyme of atrioventricular valves and semilunar valves has diverse and dynamic origins during heart development (24).

Figure 4.

Exclusive reporter systems. A, the exclusive IR5 reporter can be used to label distinct cell populations. In the Cdh5-Nigri;Tbx18-Cre;IR5 triple-positive mouse, Cdh5+ endothelial cells (including endocardial cells) are marked as ZsGreen by Nigri-nox recombination, and Tbx18+ epicardial cells are marked as tdTomato by Cre-loxP recombination. The image (right) shows the contribution of these two distinct cell populations for atrioventricular valve mesenchyme during heart development. B, in the Cdh5-Nigri;Wnt1-Cre;IR5 triple-positive mouse, Wnt1+ neural crest cells are marked as tdTomato by Cre-loxP recombination, and Cdh5+ endothelial cells (including endocardial cells) are marked as ZsGreen by Nigri-nox recombination. The image (right) shows the contribution of these two distinct cell populations for outflow track valve mesenchyme during heart development. C, the interleaved reporter 1 (IR1) can be used to label distinct cell populations. After Dre-rox recombination in Dre+ cells, all DNA sequences between these two rox sites would be removed, including a loxP site. So the next Cre-loxP recombination would not happen in Dre+ cells, and it can only happen in Dre−Cre+ cells. Taking the c-kit as an example, because the c-kit ectopic expressed in a little cardiomyocytes, the Kit-CreER;IR1 mouse (conventional strategy) could label kit+ cardiomyocytes after Cre-loxP recombination. In Tnni3-Dre;Kit-CreER;IR1 triple-positive line, firstly, all Tnni3+ cardiomyocytes (including these unwanted c-kit+Tnni3+ cardiomyocytes) can be specific labeled by Dre-rox recombination. Then after tamoxifen induction, c-kit-CreER could specifically labeled all c-kit+ cells (excluding these unwanted c-kit+Tnni3+ cardiomyocytes). ECs, endothelial cells; CM, cardiomyocyte; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; pl, parietal leaflet; sl, septal leaflet; al, aortic leaflet; ml, mural leaflet. Scale bar, 100 μm.

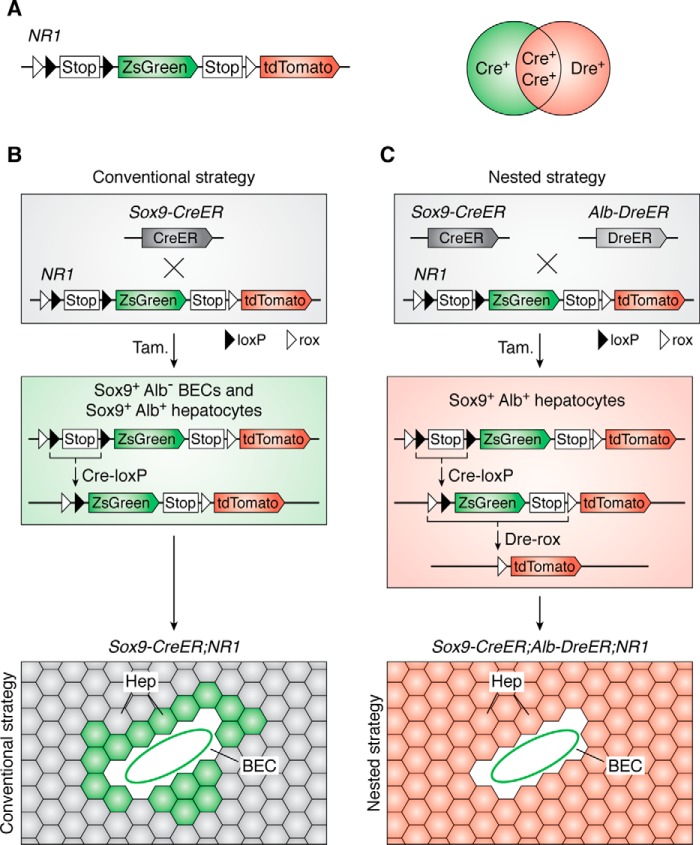

Nested reporters

During the design of a genetic lineage-tracing experiment, we sometimes encounter difficulties when the definition of a specific cell type relies on the expression of both positive and negative markers (e.g. A+B−). The Cre-loxP strategy labels all A+ cells, including the “wanted” cell type (e.g. A+B− cells) and “unwanted” cell types (e.g. A+B+ cells). In this case, we can utilize the dual nested reporter system to precisely distinguish these distinct “wanted” and “unwanted” cell types accurately. By its name, the two pairs of recombination sites are nested as follows: Rosa26-CAG-site2-site1-Stop-site1-reporter A-site2-reporter B. Nested reporters 1 (NR1) and 2 (NR2) are more appropriately designed for cell lineage tracing through the use of inducible recombination systems, such as CreER and DreER (45). The structure of NR1 is CAG-rox-loxP-Stop-loxP-ZsGreen-Stop-rox-tdTomato. In the approach using NR1, the promoter A–mediated internal recombination of Cre-loxP could result in ZsGreen expression in cell A. However, if promoter A is also activated in “unwanted” cell B (A+B+ cells), the sequences of the ZsGreen gene and two loxP sites could both be removed subsequently by an external Dre-rox recombination driven by specific promoter B in that type of cells. Thus, the final readout includes specific labeling of the Cre+Dre− cell population (A+B− cells) by the ZsGreen and of the Cre+Dre+ cell populations (A+B+ cells) by tdTomato (45). Moreover, within Cre+Dre+ cells, the recombination order of Dre-rox and Cre-loxP would not influence the final readout, which is determined by the expression of Cre and Dre. Therefore, the nested reporter system can be used to solve some controversial questions in defining the cell fate of stem cells with known specific expression of both positive and negative markers.

For example, whether Sox9+ ductal cells are progenitors of hepatocytes during liver regeneration remains controversial. Some lineage-tracing studies reported that Sox9-CreER–labeled ductal cells or biliary epithelial cells (BECs) could contribute to hepatocytes at homeostasis and after injury (68, 69). Other studies report that the newly generated hepatocytes are derived from pre-existing hepatocytes after injury (70–74). Of note, Sox9 is expressed in BECs and in some periportal hepatocytes (45, 75, 76). The BECs-to-hepatocytes conjecture based on Sox9 lineage tracing is problematic because the new hepatocytes may possibly be derived from Sox9-CreER–labeled pre-existing hepatocytes (Fig. 5A). By incorporating Sox9 and another hepatocyte-specific marker, albumin (Alb), the dual NR1 reporter can be used to distinguish Sox9+ BECs and Sox9+ hepatocytes by two different reporters through dual-recombination events. In Sox9-CreER;Alb-DreER;NR1 triple-positive mice, two kinds of recombination events can be induced by tamoxifen treatment. The Sox9+ BECs and Sox9+Alb+ hepatocytes are both labeled by ZsGreen after the first Cre-loxP recombination, but after another round of Dre-rox recombination, the Sox9+Alb+ hepatocytes will convert to express tdTomato, and so do all Alb+ hepatocytes that are labeled by a unique tdTomato reporter. Thus, the precisely labeled ZsGreen+ BECs and tdTomato+ hepatocytes can be used to reassess the contribution of Sox9+ ductal cells to hepatocytes during liver repair (Fig. 5B). In summary, such a fate-mapping analysis showed that BECs do not regenerate new hepatocytes but only proliferate to replenish BECs after CCl4-induced liver injury (45). Altogether, the nested system is valuable for distinguishing two distinct cell populations, A+B+ versus A+B−.

Figure 5.

Nested reporter systems. A, the nested NR1 reporter can be used to label distinct cell populations. The Cre+ cells are labeled as ZsGreen by Cre-loxP recombination. The Dre+Cre− cells are marked as tdTomato by Cre-loxP recombination. The final readout of Dre+Cre+ cells is tdTomato because of the final Cre-loxP recombination. B, Sox9 is not a specific marker of BECs; it also targets some hepatocytes (Hep). The readout of Sox9-CreER;NR1 line includes both BECs and hepatocytes, which is same as conventional strategy. C, in the Sox9-CreER;Alb-CreER;NR1 triple-positive mouse (nested strategy), the Sox9+Alb+ hepatocytes are finally labeled as tdTomato. So the nested reporter system is valuable for labeling distinct cell populations.

The choice of strategies mainly depends on the gene expression, mouse tools available, and scientific questions to be addressed. If the promoter A is activated specifically in A type cells of interest, a conventional single recombinase–mediated genetic approach is suitable for specific labeling of A type cells. If the promoter A is ectopically expressed in some “unwanted” B type cells (promoter is B), we can choose exclusive reporters or nested reporters to distinguish the labeling of “unwanted” A+B+ type cells. Here we need two separate recombinases (one is Dre and another is Cre), which are derived by promoter A or B, separately. The choice of which dual-reporter system depends on the types of recombination tools. If the B-mediated recombination tool is constitutive and the A-mediated recombination tool is inducible, we may use exclusive reporters to label all B+ cells (including unwanted A+B+ cells) before tamoxifen induction. If both A- and B-mediated recombinations are inducible, we should choose nested reporters to revert all B+ cells (including unwanted A+B+ cells) labeling into another unique genetic reporter after tamoxifen induction, thus distinctly and specifically labeling A+B− cells.

Conclusions and perspectives

Stem cells are crucial players in organ development, regeneration, and disease. However, the definition of stem cells and their potential in these physiological and pathological processes are unclear unless we can precisely track their lineage commitment. Owing to the efforts of this community, cell-tracing strategies have been developed for more than a century. From transplantation, transfection, and viral transduction to the recently developed and widely used approach of genetic recombination, diverse new techniques have been evolved for more specific and precise cell fate or behavioral studies. Among these techniques, genetic recombination mediated by SSR systems is one of the most powerful tools to achieve these goals. Compared with conventional tools, powerful multiple recombinase–mediated genetic approaches enhance the specificity and precision of cell fate mapping, permitting the discovery of unprecedented cell events in biological processes. Combined with live imaging, we can observe the cell behaviors more accurately and comprehensively. We could also manipulate the function of one cell lineage, such as proliferation inhibition (77), and observe the behavior of another cell lineage simultaneously to see how cell-cell communication coordinating development or tissue repair and regeneration. The new genetic systems could also be combined with CRISPR-Cas9–mediated barcoding, for more complex but higher resolution for single cell fate studies. For these iterations and wide application, more genetic tools should be developed, such as multiple recombination–mediated barcoding systems.

This work was supported by Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Grants XDA16010507 and XDB19000000 and National Science Foundation of China Grants 31730112, 31625019, 91849202, and 81761138040. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- SSR

- site-specific recombination

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- HSP

- heat shock protein

- MADM

- mosaic analysis with double markers

- BASC

- bronchioalveolar stem cell

- RFP

- red fluorescent protein

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- IRES

- internal ribosome entry site

- BEC

- biliary epithelial cell

- Alb

- albumin

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

References

- 1. Kretzschmar K., and Watt F. M. (2012) Lineage tracing. Cell 148, 33–45 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fox D. T., Morris L. X., Nystul T., and Spradling A. C. (2008) Lineage analysis of stem cells. in StemBook, Harvard Stem Cell Institute, Cambridge, MA: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buckingham M. E., and Meilhac S. M. (2011) Tracing cells for tracking cell lineage and clonal behavior. Dev. Cell 21, 394–409 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Axelrod D. (1979) Carbocyanine dye orientation in red-cell membrane studied by microscopic fluorescence polarization. Biophys. J. 26, 557–573 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85271-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weisblat D. A., Sawyer R. T., and Stent G. S. (1978) Cell lineage analysis by intracellular injection of a tracer enzyme. Science 202, 1295–1298 10.1126/science.725606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bałakier H., and Pedersen R. A. (1982) Allocation of cells to inner cell mass and trophectoderm lineages in preimplantation mouse embryos. Dev. Biol. 90, 352–362 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90384-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cotsarelis G., Sun T. T., and Lavker R. M. (1990) Label-retaining cells reside in the bulge area of pilosebaceous unit: implications for follicular stem cells, hair cycle, and skin carcinogenesis. Cell 61, 1329–1337 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90696-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braun K. M., Niemann C., Jensen U. B., Sundberg J. P., Silva-Vargas V., and Watt F. M. (2003) Manipulation of stem cell proliferation and lineage commitment: visualisation of label-retaining cells in wholemounts of mouse epidermis. Development 130, 5241–5255 10.1242/dev.00703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tumbar T., Guasch G., Greco V., Blanpain C., Lowry W. E., Rendl M., and Fuchs E. (2004) Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science 303, 359–363 10.1126/science.1092436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zong H., Espinosa J. S., Su H. H., Muzumdar M. D., and Luo L. (2005) Mosaic analysis with double markers in mice. Cell 121, 479–492 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bergmann O., Bhardwaj R. D., Bernard S., Zdunek S., Barnabé-Heider F., Walsh S., Zupicich J., Alkass K., Buchholz B. A., Druid H., Jovinge S., and Frisén J. (2009) Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 324, 98–102 10.1126/science.1164680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenquist G. C. (1981) Epiblast origin and early migration of neural crest cells in the chick embryo. Dev. Biol. 87, 201–211 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90143-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jensen K. B., Driskell R. R., and Watt F. M. (2010) Assaying proliferation and differentiation capacity of stem cells using disaggregated adult mouse epidermis. Nat. Protoc. 5, 898–911 10.1038/nprot.2010.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Rourke K. P., Loizou E., Livshits G., Schatoff E. M., Baslan T., Manchado E., Simon J., Romesser P. B., Leach B., Han T., Pauli C., Beltran H., Rubin M. A., Dow L. E., and Lowe S. W. (2017) Transplantation of engineered organoids enables rapid generation of metastatic mouse models of colorectal cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 577–582 10.1038/nbt.3837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roper J., Tammela T., Cetinbas N. M., Akkad A., Roghanian A., Rickelt S., Almeqdadi M., Wu K., Oberli M. A., Sánchez-Rivera F. J., Park Y. K., Liang X., Eng G., Taylor M. S., Azimi R., et al. (2017) In vivo genome editing and organoid transplantation models of colorectal cancer and metastasis. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 569–576 10.1038/nbt.3836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Welniak L. A., Blazar B. R., and Murphy W. J. (2007) Immunobiology of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 139–170 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu Q., Huang X., Zhang H., Tian X., He L., Yang R., Yan Y., Wang Q. D., Gillich A., and Zhou B. (2015) c-kit(+) cells adopt vascular endothelial but not epithelial cell fates during lung maintenance and repair. Nat. Med. 21, 866–868 10.1038/nm.3888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holt C. E., Garlick N., and Cornel E. (1990) Lipofection of cDNAs in the embryonic vertebrate central nervous system. Neuron 4, 203–214 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90095-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Itasaki N., Bel-Vialar S., and Krumlauf R. (1999) “Shocking” developments in chick embryology: electroporation and in ovo gene expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, E203–E207 10.1038/70231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lemischka I. R., Raulet D. H., and Mulligan R. C. (1986) Developmental potential and dynamic behavior of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell 45, 917–927 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90566-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holland E. C., and Varmus H. E. (1998) Basic fibroblast growth factor induces cell migration and proliferation after glia-specific gene transfer in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1218–1223 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodríguez C. I., Buchholz F., Galloway J., Sequerra R., Kasper J., Ayala R., Stewart A. F., and Dymecki S. M. (2000) High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat. Genet. 25, 139–140 10.1038/75973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suzuki E., and Nakayama M. (2011) VCre/VloxP and SCre/SloxP: new site-specific recombination systems for genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e49 10.1093/nar/gkq1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu K., Yu W., Tang M., Tang J., Liu X., Liu Q., Li Y., He L., Zhang L., Evans S. M., Tian X., Lui K. O., and Zhou B. (2018) A dual genetic tracing system identifies diverse and dynamic origins of cardiac valve mesenchyme. Development 145, dev167775 10.1242/dev.167775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anastassiadis K., Fu J., Patsch C., Hu S., Weidlich S., Duerschke K., Buchholz F., Edenhofer F., and Stewart A. F. (2009) Dre recombinase, like Cre, is a highly efficient site-specific recombinase in E. coli, mammalian cells and mice. Dis. Model. Mech. 2, 508–515 10.1242/dmm.003087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nagy A. (2000) Cre recombinase: the universal reagent for genome tailoring. Genesis 26, 99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tian X., Pu W. T., and Zhou B. (2015) Cellular origin and developmental program of coronary angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 116, 515–530 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alcolea M. P., and Jones P. H. (2013) Tracking cells in their native habitat: lineage tracing in epithelial neoplasia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 161–171 10.1038/nrc3460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blanpain C., and Simons B. D. (2013) Unravelling stem cell dynamics by lineage tracing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 489–502 10.1038/nrm3625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Joseph C., Quach J. M., Walkley C. R., Lane S. W., Lo Celso C., and Purton L. E. (2013) Deciphering hematopoietic stem cells in their niches: a critical appraisal of genetic models, lineage tracing, and imaging strategies. Cell Stem Cell 13, 520–533 10.1016/j.stem.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Metzger D., Ali S., Bornert J. M., and Chambon P. (1995) Characterization of the amino-terminal transcriptional activation function of the human estrogen-receptor in animal and yeast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 9535–9542 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rawlins E. L., Okubo T., Xue Y., Brass D. M., Auten R. L., Hasegawa H., Wang F., and Hogan B. L. (2009) The role of Scgb1a1+ Clara cells in the long-term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell 4, 525–534 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Madisen L., Zwingman T. A., Sunkin S. M., Oh S. W., Zariwala H. A., Gu H., Ng L. L., Palmiter R. D., Hawrylycz M. J., Jones A. R., Lein E. S., and Zeng H. (2010) A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133–140 10.1038/nn.2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Soriano P. (1999) Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 21, 70–71 10.1038/5007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Srinivas S., Watanabe T., Lin C.-S., William C. M., Tanabe Y., Jessell T. M., and Costantini F. (2001) Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev. Biol. 1, 4 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cai C. L., Liang X., Shi Y., Chu P. H., Pfaff S. L., Chen J., and Evans S. (2003) Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev. Cell 5, 877–889 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00363-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barker N., van Es J. H., Kuipers J., Kujala P., van den Born M., Cozijnsen M., Haegebarth A., Korving J., Begthel H., Peters P. J., and Clevers H. (2007) Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449, 1003–1007 10.1038/nature06196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bonaguidi M. A., Wheeler M. A., Shapiro J. S., Stadel R. P., Sun G. J., Ming G. L., and Song H. (2011) In vivo clonal analysis reveals self-renewing and multipotent adult neural stem cell characteristics. Cell 145, 1142–1155 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Livet J., Weissman T. A., Kang H., Draft R. W., Lu J., Bennis R. A., Sanes J. R., and Lichtman J. W. (2007) Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system. Nature 450, 56–62 10.1038/nature06293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Snippert H. J., van der Flier L. G., Sato T., van Es J. H., van den Born M., Kroon-Veenboer C., Barker N., Klein A. M., van Rheenen J., Simons B. D., and Clevers H. (2010) Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143, 134–144 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu C., Sage J. C., Miller M. R., Verhaak R. G., Hippenmeyer S., Vogel H., Foreman O., Bronson R. T., Nishiyama A., Luo L., and Zong H. (2011) Mosaic analysis with double markers reveals tumor cell of origin in glioma. Cell 146, 209–221 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sereti K. I., Nguyen N. B., Kamran P., Zhao P., Ranjbarvaziri S., Park S., Sabri S., Engel J. L., Sung K., Kulkarni R. P., Ding Y., Hsiai T. K., Plath K., Ernst J., Sahoo D., et al. (2018) Analysis of cardiomyocyte clonal expansion during mouse heart development and injury. Nat. Commun. 9, 754 10.1038/s41467-018-02891-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Henner A., Ventura P. B., Jiang Y., and Zong H. (2013) MADM-ML, a mouse genetic mosaic system with increased clonal efficiency. PLoS ONE 8, e77672 10.1371/journal.pone.0077672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhao H., and Zhou B. (2019) Dual genetic approaches for deciphering cell fate plasticity in vivo: more than double. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 61, 101–109 10.1016/j.ceb.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. He L., Li Y., Li Y., Pu W., Huang X., Tian X., Wang Y., Zhang H., Liu Q., Zhang L., Zhao H., Tang J., Ji H., Cai D., Han Z., et al. (2017) Enhancing the precision of genetic lineage tracing using dual recombinases. Nat. Med. 23, 1488–1498 10.1038/nm.4437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang H., Pu W., Tian X., Huang X., He L., Liu Q., Li Y., Zhang L., He L., Liu K., Gillich A., and Zhou B. (2016) Genetic lineage tracing identifies endocardial origin of liver vasculature. Nat. Genet. 48, 537–543 10.1038/ng.3536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu Q., Liu K., Cui G., Huang X., Yao S., Guo W., Qin Z., Li Y., Yang R., Pu W., Zhang L., He L., Zhao H., Yu W., Tang M., et al. (2019) Lung regeneration by multipotent stem cells residing at the bronchioalveolar-duct junction. Nat. Genet. 51, 728–738 10.1038/s41588-019-0346-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Madisen L., Garner A. R., Shimaoka D., Chuong A. S., Klapoetke N. C., Li L., van der Bourg A., Niino Y., Egolf L., Monetti C., Gu H., Mills M., Cheng A., Tasic B., Nguyen T. N., et al. (2015) Transgenic mice for intersectional targeting of neural sensors and effectors with high specificity and performance. Neuron 85, 942–958 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Giangreco A., Reynolds S. D., and Stripp B. R. (2002) Terminal bronchioles harbor a unique airway stem cell population that localizes to the bronchoalveolar duct junction. Am. J. Pathol. 161, 173–182 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64169-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim C. F., Jackson E. L., Woolfenden A. E., Lawrence S., Babar I., Vogel S., Crowley D., Bronson R. T., and Jacks T. (2005) Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell 121, 823–835 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee J. H., Bhang D. H., Beede A., Huang T. L., Stripp B. R., Bloch K. D., Wagers A. J., Tseng Y. H., Ryeom S., and Kim C. F. (2014) Lung stem cell differentiation in mice directed by endothelial cells via a BMP4-NFATc1-thrombospondin-1 axis. Cell 156, 440–455 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hirrlinger J., Scheller A., Hirrlinger P. G., Kellert B., Tang W., Wehr M. C., Goebbels S., Reichenbach A., Sprengel R., Rossner M. J., and Kirchhoff F. (2009) Split-Cre complementation indicates coincident activity of different genes in vivo. PLoS ONE 4, e4286 10.1371/journal.pone.0004286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Salwig I., Spitznagel B., Vazquez-Armendariz A. I., Khalooghi K., Guenther S., Herold S., Szibor M., and Braun T. (2019) Bronchioalveolar stem cells are a main source for regeneration of distal lung epithelia in vivo. EMBO J. 38, e102099 10.15252/embj.2019102099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Awatramani R., Soriano P., Rodriguez C., Mai J. J., and Dymecki S. M. (2003) Cryptic boundaries in roof plate and choroid plexus identified by intersectional gene activation. Nat. Genet. 35, 70–75 10.1038/ng1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jensen P., Farago A. F., Awatramani R. B., Scott M. M., Deneris E. S., and Dymecki S. M. (2008) Redefining the serotonergic system by genetic lineage. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 417–419 10.1038/nn2050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yamamoto M., Shook N. A., Kanisicak O., Yamamoto S., Wosczyna M. N., Camp J. R., and Goldhamer D. J. (2009) A multifunctional reporter mouse line for Cre- and FLP-dependent lineage analysis. Genesis 47, 107–114 10.1002/dvg.20474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu K., Tang M., Jin H., Liu Q., He L., Zhu H., Liu X., Han X., Li Y., Zhang L., Tang J., Pu W., Lv Z., Wang H., Ji H., and Zhou B. (2020) Triple-cell lineage tracing by a dual reporter on a single allele. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 690–700 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Han X., Wang Y., Pu W., Huang X., Qiu L., Li Y., Yu W., Zhao H., Liu X., He L., Zhang L., Ji Y., Lu J., Lui K. O., and Zhou B. (2019) Lineage tracing reveals the bipotency of SOX9+ hepatocytes during liver regeneration. Stem Cell Reports 12, 624–638 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Engleka K. A., Manderfield L. J., Brust R. D., Li L., Cohen A., Dymecki S. M., and Epstein J. A. (2012) Islet1 derivatives in the heart are of both neural crest and second heart field origin. Circ. Res. 110, 922–926 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.266510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Liu K., Tang M., Liu Q., Han X., Jin H., Zhu H., Li Y., He L., Ji H., and Zhou B. (2020) Bi-directional differentiation of single bronchioalveolar stem cells during lung repair. Cell Discov. 6, 1 10.1038/s41421-019-0132-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ellison G. M., Vicinanza C., Smith A. J., Aquila I., Leone A., Waring C. D., Henning B. J., Stirparo G. G., Papait R., Scarfò M., Agosti V., Viglietto G., Condorelli G., Indolfi C., Ottolenghi S., et al. (2013) Adult c-kit(pos) cardiac stem cells are necessary and sufficient for functional cardiac regeneration and repair. Cell 154, 827–842 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liu Q., Yang R., Huang X., Zhang H., He L., Zhang L. B., Tian X., Nie Y., Hu S., Yan Y., Zhang L., Qiao Z., Wang Q. D., Lui K. O., and Zhou B. (2016) Genetic lineage tracing identifies in situ Kit-expressing cardiomyocytes. Cell Res. 26, 119–130 10.1038/cr.2015.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. de Lange F. J., Moorman A. F., Anderson R. H., Männer J., Soufan A. T., de Gier-de Vries C., Schneider M. D., Webb S., van den Hoff M. J., and Christoffels V. M. (2004) Lineage and morphogenetic analysis of the cardiac valves. Circ. Res. 95, 645–654 10.1161/01.RES.0000141429.13560.cb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lincoln J., Alfieri C. M., and Yutzey K. E. (2004) Development of heart valve leaflets and supporting apparatus in chicken and mouse embryos. Dev. Dyn. 230, 239–250 10.1002/dvdy.20051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rivera-Feliciano J., Lee K. H., Kong S. W., Rajagopal S., Ma Q., Springer Z., Izumo S., Tabin C. J., and Pu W. T. (2006) Development of heart valves requires Gata4 expression in endothelial-derived cells. Development 133, 3607–3618 10.1242/dev.02519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jiang X., Rowitch D. H., Soriano P., McMahon A. P., and Sucov H. M. (2000) Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development 127, 1607–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nakamura T., Colbert M. C., and Robbins J. (2006) Neural crest cells retain multipotential characteristics in the developing valves and label the cardiac conduction system. Circ. Res. 98, 1547–1554 10.1161/01.RES.0000227505.19472.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Furuyama K., Kawaguchi Y., Akiyama H., Horiguchi M., Kodama S., Kuhara T., Hosokawa S., Elbahrawy A., Soeda T., Koizumi M., Masui T., Kawaguchi M., Takaori K., Doi R., Nishi E., et al. (2011) Continuous cell supply from a Sox9-expressing progenitor zone in adult liver, exocrine pancreas and intestine. Nat. Genet. 43, 34–41 10.1038/ng.722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tarlow B. D., Finegold M. J., and Grompe M. (2014) Clonal tracing of Sox9+ liver progenitors in mouse oval cell injury. Hepatology 60, 278–289 10.1002/hep.27084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yanger K., Knigin D., Zong Y., Maggs L., Gu G., Akiyama H., Pikarsky E., and Stanger B. Z. (2014) Adult hepatocytes are generated by self-duplication rather than stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 15, 340–349 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schaub J. R., Malato Y., Gormond C., and Willenbring H. (2014) Evidence against a stem cell origin of new hepatocytes in a common mouse model of chronic liver injury. Cell Reports 8, 933–939 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Malato Y., Naqvi S., Schürmann N., Ng R., Wang B., Zape J., Kay M. A., Grimm D., and Willenbring H. (2011) Fate tracing of mature hepatocytes in mouse liver homeostasis and regeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4850–4860 10.1172/JCI59261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tarlow B. D., Pelz C., Naugler W. E., Wakefield L., Wilson E. M., Finegold M. J., and Grompe M. (2014) Bipotential adult liver progenitors are derived from chronically injured mature hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell 15, 605–618 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang Y., Huang X., He L., Pu W., Li Y., Liu Q., Li Y., Zhang L., Yu W., Zhao H., Zhou Y., and Zhou B. (2017) Genetic tracing of hepatocytes in liver homeostasis, injury, and regeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 8594–8604 10.1074/jbc.M117.782029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Font-Burgada J., Shalapour S., Ramaswamy S., Hsueh B., Rossell D., Umemura A., Taniguchi K., Nakagawa H., Valasek M. A., Ye L., Kopp J. L., Sander M., Carter H., Deisseroth K., Verma I. M., and Karin M. (2015) Hybrid periportal hepatocytes regenerate the injured liver without giving rise to cancer. Cell 162, 766–779 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yanger K., Zong Y., Maggs L. R., Shapira S. N., Maddipati R., Aiello N. M., Thung S. N., Wells R. G., Greenbaum L. E., and Stanger B. Z. (2013) Robust cellular reprogramming occurs spontaneously during liver regeneration. Gene Dev. 27, 719–724 10.1101/gad.207803.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pu W., Han X., He L., Li Y., Huang X., Zhang M., Lv Z., Yu W., Wang Q. D., Cai D., Wang J., Sun R., Fei J., Ji Y., Nie Y., and Zhou B. (2020) A genetic system for tissue-specific inhibition of cell proliferation. Development 147, dev183830 10.1242/dev.183830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]