Abstract

Objective:

Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) poses a major challenge to the healthcare system. We assessed factors that should be considered when designing sub-processes of a C. difficile infection (CDI) prevention bundle.

Design:

Phenomenological qualitative study.

Methods:

We conducted three focus groups of environmental services (EVS) staff, physicians, and nurses to assess their perspectives on a CDI prevention bundle. We used the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model to examine five sub-processes of the CDI bundle: diagnostic testing, empiric isolation, contact isolation, hand hygiene, and environmental disinfection. We coded transcripts to the five SEIPS elements and ensured scientific rigor. We assessed for common, unique, and conflicting factors across stakeholder groups and sub-processes of the CDI bundle.

Results:

Each focus group lasted 1.5 hours on average. Common work system barriers included inconsistencies in knowledge and practice of CDI management procedures; increased workload; poor setup of aspects of the physical environment (e.g., inconvenient location of sinks); and inconsistencies in CDI documentation. Unique barriers and facilitators were related to specific activities performed by the stakeholder group. For instance, algorithmic approaches used by physicians facilitated timely diagnosis of CDI. Conflicting barriers or facilitators were related to opposing objectives, e.g., clinicians needing rapid placement of a patient in a room while EVS needed time to disinfect the room.

Conclusions:

A systems engineering approach can help to holistically identify factors that influence successful implementation of sub-processes of infection prevention bundles.

INTRODUCTION

Despite many efforts towards its prevention, Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) continues to pose a major challenge to the healthcare system.1 C. difficile is a major healthcare-associated pathogen and the most common infectious cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea, resulting in high morbidity and mortality, increased healthcare utilization and costs, and prolonged hospital stays.2 Prevention of C. difficile infection (CDI) is challenging; therefore, innovative integration of numerous control methods has been developed, albeit with limited success.3,4 Consequently, many professional organizations such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) recommend an infection control “bundle” strategy for CDI control and prevention.5

A CDI bundle is comprised of individual intervention components as part of a larger process; we refer to these as “sub-processes.” They include diagnostic testing, empiric isolation, contact isolation, hand hygiene, and environmental disinfection. Successful implementation of these sub-processes is dependent upon multiple stakeholders including physicians, nurses, nursing assistants, environmental services personnel, families/caregivers, and others who interact with patients.6,7 It is important to understand how these different stakeholders are affected by and must comply with sub-processes for successful implementation of the entire CDI bundle.

In our previous work, using a human factors approach and focusing on nurses’ perspectives, we demonstrated that work system barriers and facilitators were associated with all bundle sub-processes.6 In this paper, we extend the scope of our previous work by examining perspectives of three stakeholder groups (i.e., environmental services personnel, physicians, and nurses) at the forefront of CDI prevention. Yanke et al. have done similar work, but unlike an academic teaching hospital where we conducted our study, their setting was a Veteran Affairs hospital and some of the bundle sub-processes were different than the ones we assess here.8 This approach of incorporating multiple perspectives in the context of system design has been successfully applied elsewhere.9–11

In this study, we use a human factors and systems engineering approach and incorporate the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model as our conceptual framework.12–14 This model has been used widely in infection prevention.15,16 The SEIPS model focuses on five elements of the work system — person, tasks, tools and technologies, physical environment, and organizational conditions.17 These interact and may create barriers or facilitators to completion of sub-processes of the CDI bundle.

In this paper, we aim to answer the question: “What must be considered when designing sub-processes as part of the overall C.difficile bundle when multiple stakeholders are involved?” This includes consideration of common, unique (to a stakeholder group) and conflicting work system barriers and facilitators i.e., when a facilitator for one stakeholder group is a barrier for another.

METHODS

Setting

This study was performed at a large academic teaching hospital in the Midwestern U.S. It is part of a larger study with a goal of conducting a work system analysis to better understand factors that facilitate or hinder implementation of a “bundle” of CDI prevention practices – what we refer to here as “sub-processes” (i.e., diagnostic testing, empiric isolation, contact isolation, hand hygiene, disinfection). In Table 1, we provide components of the C.difficile bundle of the institution during the study period. This study was approved by the organization’s Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Components of the C. difficile prevention bundle at the study institution

| 1. Enhanced contact precautions measures for patients with C. difficile infection (CDI) | |

Hospital Precautions

|

Staff specific precautions

|

| 2. C. difficile diagnostic testing | |

| When to test… | |

Adults

|

Pediatric

|

DO NOT test… (Applicable to adult and pediatric)

| |

3. Environmental disinfection

| |

Data Collection

We conducted three focus groups with the following stakeholder groups: 1) environmental services (EVS) workers (i.e., housekeepers), 2) physicians, and 3) nurses (Table 2). A human factors engineer facilitated each focus group. An Infectious Disease physician served as content expert and a logistician assisted the group process. The discussions were audio recorded and transcribed. We used phenomenology, a qualitative research method that is used to describe how participants experience a certain phenomenon, in this case the C. difficile bundle and its sub-processes. Phenomenology allows the researcher to assess the perceptions, perspectives, and understandings of individuals who have actually experienced the phenomenon or situation of interest.18 Further details regarding the methods used in the focus groups are reported elsewhere.7

Table 2.

Focus group participants

| Group | N | Gender | Experience | Unit/service work on |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVS | 6 | 4 female, 2 male | 2 – 30 years | Medicine, surgery & intensive care units |

| Physicians | 8 | 3 female, 5 male | 7 residents (with 2–3 years) 1 attending (1 year) |

Internal medicine |

| Nursing | 10 | 10 female, 0 male | Varying | Medical units |

Data Analysis

Two researchers independently reviewed the transcripts and identified work system barriers19 and facilitators.20 Each identified barrier and facilitator was coded to: 1) the work system element, 2) the associated CDI sub-process, 3) whether it was a barrier or facilitator, and 4) the role (i.e., EVS, physician, nurse). (Online Supplement 1) The two researchers met and compared coding for each transcript with discussion of any discrepancies. Agreed upon coding was then recorded in Dedoose® content analysis software and later downloaded for in-depth analysis of each sub-process.

Using the constant comparison method in which data are repeatedly analyzed and compared,21 we conducted sub-process analysis by first sorting the coded data by sub-process, then by work system element, then by barrier or facilitator, and finally by role. This allowed for ease of comparing common, unique, and conflicting work system barriers and facilitators for each sub-process by role.

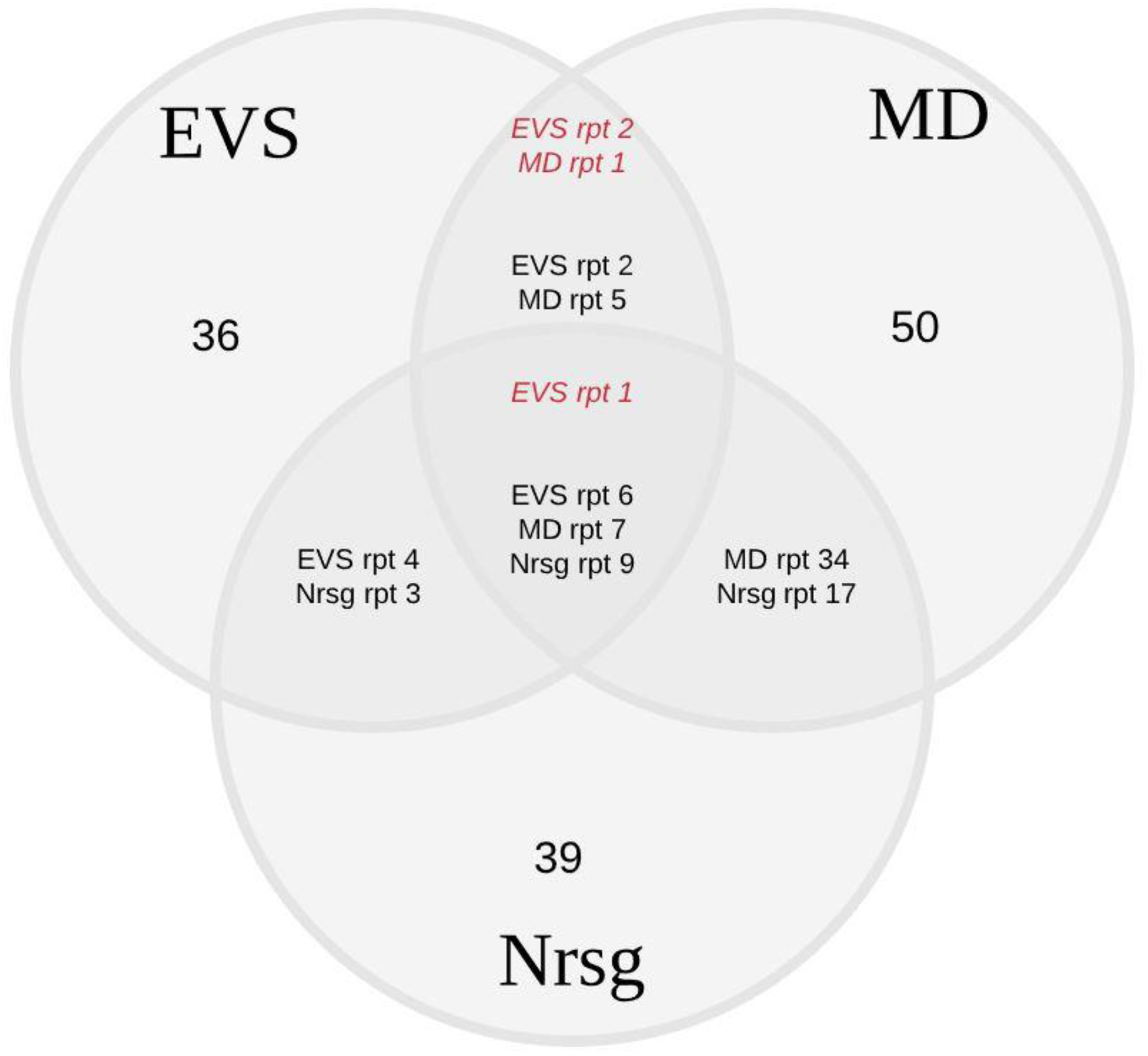

RESULTS

There were 24 participants in three focus groups (each lasting 1.5 hours): six EVS workers, 8 physicians, and 10 nurses. In the following text, we present results for each of the five sub-processes of the CDI prevention bundle. Verbatim quotations (Q#) are presented in Online Supplement 2. A summary of work system barriers and facilitators by sub-process by role is found in Table 3. Common, unique, and conflicting work system data are displayed in Table 4 and in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Sub-process Work System Barriers and Facilitators by Focus Group

| Sub-process | Barriers | Facilitators | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | T | T/T | Orgn | PE | P | T | T/T | Orgn | PE | Total B/F^ | |

| Diagnostic testing | |||||||||||

| EVS* | |||||||||||

| MD* | 9 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 7 | ||||||

| Nursing | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Total | 12 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 38 | ||||

| Empiric isolation | |||||||||||

| EVS | |||||||||||

| MD | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| Nursing | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Total | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 16 | ||

| Contact isolation | |||||||||||

| EVS | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| MD | 4 | 3 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Nursing | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Total | 8 | 11 | 16 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 56 | ||

| Hand hygiene | |||||||||||

| EVS | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | ||||||

| MD | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Nursing | 3 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Total | 6 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 14 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 50 | ||

| Disinfection | |||||||||||

| EVS | 6 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| MD | 8 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Nursing | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Total | 1 | 6 | 12 | 17 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 46 | ||

Note. EVS, environmental services; MD, physicians; B = barrier; F, facilitator; P, person; T = task; T/T, tool/technology; Orgn, organization; PE, physical environment. Blank space means 0.

Table 4.

Number of Common, Unique and Conflicting Work System Barriers and Facilitators by Sub-process for Three Focus Groups

| person | task | tool/technology | organization | physical environment | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Testing | common | unique | conflicting | common | unique | conflicting | common | unique | conflicting | common | unique | conflicting | common | unique | conflicting |

| EVS | |||||||||||||||

| MD | 4(B)+ | 5(B) | 1(F) | 3(B); 2(F) | 3(B); 6(F) | 2(B); 1(F) | |||||||||

| Nrsg | 1(B) | 2(B); 1(F) | 1(F) | 2(B); 2(F) | 2(B) | ||||||||||

| Empiric Isolation | |||||||||||||||

| EVS | |||||||||||||||

| MD | 1(B) | 3(B) | 1(B); 1(F) | 3(B); 3(F) | 1(F) | ||||||||||

| Nrsg | 1(B) | 1(B) | 1(F) | ||||||||||||

| Contact Isolation | |||||||||||||||

| EVS | 1(B) | 1(B) | 1(B); 1(F) | 1(B); 1(F) | 3(B) | 1(F) | |||||||||

| MD | 3(B) | 1(B) | 3(B) | 5(B); 2(F) | 6(B) | 1(B); 3(F) | 1(F) | ||||||||

| Nrsg | 3(B) | 1(B) | 4(B) | 2(B); 2(F) | 2(B) | 1(B); 2(F) | 2(B); 1(F) | ||||||||

| Hand Hygiene | |||||||||||||||

| EVS | 2(B) | 1(B); 3(F) | 2(F) | 4(B) | 1(B) | 2(B) | |||||||||

| MD | 3(B) | 3(B); 2(F) | 1(B) | 2(B); 1(F) | 5(B) | ||||||||||

| Nrsg | 3(B) | 2(B); 2(F) | 1(B) | 2(F) | 5(B) | 2(B); 1(F) | |||||||||

| Disinfection | |||||||||||||||

| EVS | 1(F) | 6(B) | 3(B); 1(F) | 1(B) | 8(B) | 1(B) | 1(B) | 2(B); 1(F) | |||||||

| MD | 8(B); 1(F) | 1(B) | |||||||||||||

| Nrsg | 1(B) | 1(B); 1(F) | 1(B) | 5(B) | 1(B) | 1(B) | |||||||||

Note. EVS, environmental services; MD, physicians; Nrsg, nursing; (B) = Barrier; (F), Facilitator. Blank space means 0.

Figure 1.

Number of Common, Unique, and Conflicting Work System Barriers and Facilitators for the Three Focus Groups.

Italicized text refers to conflicting barriers and facilitators, i.e., when a barrier for one group is a facilitator for another. Note. EVS = environmental services; MD = physicians; Nrsg = nursing; rpt = report

Diagnostic testing

Only the physician and nurse focus groups discussed the diagnostic testing sub-process. Physicians described person-related barriers to identifying CDI that included synthesizing information from patients presenting with multiple complicated conditions (Q1). For trainee physicians, recognizing when to suspect CDI versus antibiotic-associated diarrhea alone was a challenge. Trainee physicians also reported that peer influence sometimes results in either over-ordering tests to avoid embarrassment for missing the diagnosis, or under-ordering tests to avoid unnecessary precautions if CDI is not confirmed. (Q2) Nurses identified challenges in recognizing the need to order a diagnostic test because they perceived that patients do not want to be “embarrassed” or “bother” the nurse to discuss their diarrhea. (Q3) Physicians and nurses concurred when they described barriers associated with obtaining an accurate history or appropriately identifying signs of CDI. Only nurses described facilitators associated with the person element; it related to their clinical experience and ability to recognize CDI based on odor and appearance of the stool sample. (Q4)

Physicians reported barriers associated with the electronic health record (EHR; i.e., a technology) including inconsistent location and documentation of symptoms and signs. Another barrier was that EHR alerts or flags that inform clinicians of a patient’s recent CDI diagnosis are automatically removed 90 days after CDI diagnosis. Physicians also described overuse of email to clinicians, which is less efficient than the EHR in conveying CDI-related (and other) policies and procedures. They also identified design aspects of the EHR that facilitate information finding and both the physicians and nurses reported that EHR design made it easy to place orders. (Q5)

Physicians described organization barriers such as inadequate information when patients are transferred from other healthcare facilities. Nurses reported that inconsistent practices for CDI patients across units is a barrier in caring for these patients. (Q6) Other organization barriers identified by both nurses and physicians were related to poor communication 1) between different roles caring for CDI patients and 2) at handoff between shifts. Physicians reported that nurses’ ability to place orders for diagnostic tests when they suspect CDI facilitated patient care by expediting the diagnostic process. Both focus groups described an organization facilitator: a heightened awareness by clinical staff of CDI (Q7) and the responsiveness of other services (e.g., Lab) to test or for information requests regarding CDI.

Empiric isolation

Person-related barriers unique to physicians included the belief that CDI is not foremost on a physician’s mind when taking a patient’s history and conducting a physical examination. In addition, physicians reported that there is variation among physicians regarding ordering practices for C.difficile testing. This is because these physicians may be uncertain of CDI versus antibiotic associated diarrhea (Q8). Physicians and nurses discussed that patients with suspected CDI sometimes become overwhelmed by and may not understand why healthcare workers must take isolation precautions (Q9). Physicians confirmed that taking precautions (e.g., donning gowns and gloves) slows down rounds (i.e., a task barrier), although the ability to give verbal orders expedites (i.e., facilitates) their work (10).

Physicians listed barriers related to technology use including difficulty getting access to a computer, hence delays in writing orders. Physicians reported that an isolation order is automatically generated when placing a diagnostic test order. This facilitates the process of empiric isolation.

Nurses reported that receiving incomplete patient information upon transfer from the emergency department was an organization barrier. Physicians identified nurses’ ability to place a diagnostic test order independent of the physician as an organization facilitator (Q11). In the facility where this study was conducted, nurses could place laboratory orders to test for CDI within the first 72 hours of patient admission if there was high suspicion of CDI based on clinical findings such as diarrhea or patient history such as recent antibiotic therapy.

Nurses reported that all patient rooms (physical environment) are isolation-eligible. This was another facilitator to executing empiric isolation.

Contact isolation

Both physicians and nurses discussed negative consequences (i.e., barriers) associated with a lack of knowledge or awareness regarding CDI. For example, physicians reported hearing conflicting evidence concerning contact isolation procedures (Q12) and nurses discussed instances when care team members, despite entering a patient’s room, did not follow contact isolation procedures because they did not have direct physical contact with the patient or items in the patient’s room. (Q13) Both groups discussed negative consequences of delays in posting isolation signs. In addition, both groups talked about patients’ negative reaction to everyone entering their room wearing gowns and gloves (Q9).

All three groups (physicians, nurses, EVS staff) described the increased workload (task barriers) associated with contact isolation. Physicians described slower rounds, EVS staff described additional hand-washing procedures, and nurses identified both issues. Nurses and physicians described delays in stocking necessary supplies for CDI patients, thus delaying or extending rounds. EVS staff described increased workload and lost time when, to facilitate access to a patient by the healthcare team, they must leave a patient room (and have to return later) so the team can efficiently complete rounds (Q14). In this case, expedited access to the patient by the healthcare team (a facilitator) conflicts with effective room cleaning by EVS staff. Task-related facilitators identified by nurses included using slow periods to ensure adequate stocking of contact isolation supplies.

EVS staff reported that occasionally non-EVS staff prematurely remove signs prior to cleaning a discharged CDI patient’s room, a barrier to contact isolation compliance. Physicians described that taking other tools and technologies (e.g., computers, food trays, pagers) into a patient room pose potential for colonization of this equipment by C. difficile. Nurses reported that it was challenging to put on gloves immediately after washing their hands. EVS staff and physicians explained how “excessive” sign use sometimes caused them to overlook contact isolation precaution signs (Q15). Nurses and physicians described that sometimes they run out of supplies (e.g., gowns) needed to comply with contact precautions. All three focus groups discussed a common barrier of feeling hot when wearing gowns. Tool-related facilitators discussed by EVS and physician focus groups included benefits of “appropriate” sign use to ensure precaution compliance. Nurses and EVS staff identified strategies that facilitate their work including the use of pagers by supervisors to ensure staff awareness of CDI patient rooms. Nurses described using larger carts to meet additional supply demands of CDI patients.

Each focus group identified different organization barriers. EVS staff discussed the negative consequences of significant staff turnover and consequent training needs (Q16), physicians talked about pressure from peers to not over-order diagnostic tests, and nurses described confusion due to constantly changing CDI policies (Q17). Physicians noted that clinical team member assistance such as a recommendation by an experienced nurse facilitates CDI procedure compliance. Nurses spoke positively about the organization’s policy that considers CDI patient volume when assigning nurse-patient ratios.

From a physical environment perspective, EVS staff noted that seeing a bag of gowns outside a patient room is a visual cue to follow contact isolation precautions (i.e., a facilitator) and physicians stated that supply cabinets provide a common location for storing gowns.

Hand hygiene

Nurses and physicians reported a lack of common awareness regarding when hand hygiene and glove use should be practiced when caring for a patient with suspected or confirmed CDI (Q18). They also reported breakdowns in compliance with contact precautions that result when other staff fail to post isolation precautions signs (Q19). All of these are person-related barriers.

EVS staff reported that having to perform hand hygiene multiple times for a single room (a task barrier) increases workload.

Participants from all three focus groups reported difficulty putting on gloves immediately after applying hand hygiene gel (Q20), physicians and nurses talked about inconsistency of door sign content, and nurses pointed out the drying effect of excessive hand hygiene – all tool-related barriers. EVS staff commented positively on signs noting CDI rooms. Physicians and EVS staff stated that soap is always available. Facilitators also included strategies by nurses and EVS staff to use larger size gloves after applying hand hygiene gel. All three groups reported that signs placed on gel dispensers provide clear hand hygiene instructions.

EVS staff and physicians identified organization barriers to hand hygiene. EVS staff reported the impact of high staff turnover on hand hygiene awareness, and time pressure associated with having to leave a patient’s room at a physician’s request without performing proper hand hygiene (Q21). Physicians reported inconsistent understanding of where to perform hand hygiene (Q22) and problems resulting when all team members are not present in a CDI patient’s room during rounds. An organization facilitator noted by the physicians was the support interns receive from nurses. Nurses talked about peer support for monitoring CDI patients.

Nurses also described physical environment barriers associated with patients trying to access the soap dispenser and the lack of foot pedals on sinks in patient rooms. Foot pedals on hallway sinks facilitated hand washing without contamination of the sink by hands. Common barriers associated with sink use were identified by all three focus groups including challenges accessing the sinks due to their location, the number of sinks on a unit, and clutter interfering with access to sinks.

Disinfection

Nurses reported that keeping the supply cabinets organized and clean was a challenge. This is due to the large number of people who access it (Q23). EVS staff stated that patients preferred the smell of the current room cleaner (Oxycide®) compared to bleach, as previously used.

All task barriers were identified during the EVS focus group and related to the timing and special requirements associated with disinfection of CDI patient rooms. Workflow is negatively affected when EVS staff receive “stat” or urgent requests to immediately clean a room (Q24). Workflow is also affected when clinicians wish to enter a patient room during disinfection. EVS staff perceive the convenience afforded to clinicians supersedes EVS staff work. Finally, needing to change curtains in a patient room adversely affects workflow (Q25) as does patients being on multiple external devices and lines because EVS personnel generally do not handle such equipment, yet they have to clean around it.

EVS staff identified barriers to tool and technology availability for rooms of discharged patients, including delayed access to disinfection machines and premature removal of isolation signs posted on patient doors (Q26). Use of pens, computers, pagers, and stethoscopes pose challenges for physicians to determine whether disinfection is necessary. Nurses talked about medications taken into a patient room that, if not used, must be disposed of outside the room because they cannot be disinfected. Each focus group identified one tool or technology that facilitated room disinfection (Q27).

EVS staff talked extensively about organizational barriers associated with high staff turnover, training, scheduling, and work expectations by supervisors and clinicians. Nurses talked about having an inadequate understanding of disinfection techniques and organizational decisions resulting in an insufficient number of medication scanners, thus frequently compromising appropriate use. EVS staff and nurses talked about a lack of clarity regarding their respective responsibilities in disinfection. Physicians reported that they place pressure on EVS staff to expeditiously clean a discharged CDI patient’s room in order to facilitate a new admission despite the potentially negative consequence of rushed room disinfection (Q28). Although a common barrier (i.e., rushed cleaning may compromise disinfection), the fact that physicians request “stat” cleaning presents conflicting goals between them and EVS staff.

Elements of the physical environment pose barriers to EVS staff trying to adequately disinfect CDI patients’ rooms, such as when clean curtains are not available or when patient’s personal supplies clutter the room. Nurses were unsure of what aspects of the physical environment need to be disinfected (e.g., white boards). They also viewed excessive equipment and furniture in the room as interfering with the disinfection process. EVS staff discussed the positive presence of bags of gowns that helps them to anticipate a CDI patient’s room.

DISCUSSION

We identified unique, common, and conflicting work system barriers and facilitators across sub-processes of the CDI bundle as perceived by different stakeholders who provide care to patients infected with C.difficile. We discuss these and their relevance to patient care below.

Common barriers and facilitators

Issues of information gathering from patients and inconsistencies between peers in their knowledge and practice of CDI procedures point to the challenges of working with others to ensure complete and consistent information acquisition and sharing. Variation in understanding and enforcement of the institutional CDI prevention guidelines was associated with inconsistency in CDI practices. This points to the need for adequate feedback to stakeholders involved in infection prevention processes as a means of confirming knowledge, heightening awareness, and promoting interprofessional collaboration.8

Increased workload was associated with contact precautions compliance. Infection prevention practices such as donning and doffing gowns and gloves add to workload. Although the recommendation for contact precautions is included in many clinical practice guidelines for prevention of healthcare-associated infections, including those by the IDSA and SHEA,5 negative consequences such as less healthcare worker contact with patients have been reported.22 In addition, participants in this study were generally skeptical about the impact of contact precautions in preventing transmission of infections. This may be the reason for non-adherence to contact precautions reported by some participants. This skepticism may stem from literature showing that discontinuation of contact precautions was not associated with an increase in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or vancomycin-resistant enterococci.23,24

The design of tools and technology such as the challenge of putting on and taking off gloves coupled with handwashing requirements prior to putting gloves on and a feeling of excessive heat while wearing gowns needs to be addressed. These findings demonstrate the need to pay particular attention to the design and function of tools and technologies necessary for the success of work system interventions (i.e., the CDI bundle).

The poor design and/or location of elements of the physical environment (e.g., sinks) and means of providing storage for patient belongings as well as tools and technologies required for patient care can interfere with effective, efficient infection prevention practices.25

Another common barrier was that policies and procedures were frequently written with a given stakeholder group in mind since they are closely related to tasks the group must perform. Although this practice is useful, we recommend that policies and procedures should be created with consideration of all HCWs’ needs because of the potential overlap in the tasks they perform.

The main common facilitator was the organization-wide mindfulness of CDI and associated responsiveness by support services when making the diagnosis. This facilitated management of C.difficile infected patients.

Unique barriers and facilitators

Physicians

Varying abilities to synthesize relevant information from patients’ histories and apply algorithmic approaches to effectively and accurately identify CDI patients26 were reported as both barriers and facilitators. This can facilitate or complicate management of CDI patients. Physicians faced barriers related to the EHR involving inconsistency in CDI documentation and lack of clarity concerning whether to disinfect devices team members bring into patient rooms (e.g., pages, pens). It is critical for stakeholders to understand when to disinfect what tools and technologies they use.

Nurses

Nurses reported occasional challenges in successfully engaging patients to collect stool samples. Patients must be educated about their care, including why stool samples need to be collected. Patient education has been shown to increase their acceptance of certain infection prevention practices.27

Environmental services

Issues with access to cleaning and disinfection equipment was a problem. Organizations need to store this equipment in areas accessible to EVS staff. The requirement of complying with room disinfection standards within the limited time to clean a room was another challenge. The EVS need to be provided with adequate time to properly clean patient rooms.

Conflicting barriers and facilitators

Conflicting barriers/facilitators related to opposing objectives of HCWs: clinicians wanting ready access to a patient (even if their room is being disinfected) and promptly rooming a newly admitted patient versus EVS staff whose goal is to efficiently and effectively clean/disinfect a patient room. The interruption and/or pressure to expeditiously disinfect a room may compromise the quality of the room disinfection. This problem can be solved by proper coordination and communication between the clinical team and EVS leadership and staff.

Whereas all work system barriers identified here must be addressed through system improvement or (re)design, those identified by more than one group require careful attention. Assurance that resolving the barrier for one group does not exacerbate the barrier for another requires a careful interdisciplinary systems approach. Likewise, when a barrier for one group is a facilitator for another, the sub-process design must consider this and either resolve or minimize the conflict through interdisciplinary efforts.

This study had some limitations. It was conducted in one organization and only captured work systems barriers and facilitators incurred by three groups of HCWs. These three represent those who must comply with all or the majority of the CDI sub-processes discussed here and are the stakeholders who most commonly interact with these patients. There are ancillary staff such as pharmacists who are affected by a lessor number of sub-processes, generally only contact isolation and hand hygiene. Majority of the physicians interviewed were residents in training, it is unknown whether their perspective is similar to that of more experienced physicians. However, this presents a unique opportunity for intervention such as more training in infection control. Moreover, in teaching hospitals, these frontline physicians write most of the initial patient orders including orders related to managing CDI. The perspectives gathered were only hospital-based whereas gaining an understanding from others outside the hospital, especially addressing challenges of information gathering and sharing, would be useful. In addition, the patient and caregiver perspective is missing. Comments made by others that attempted to represent the patient may be incomplete or even inaccurate.

In conclusion, sub-processes of a “system” (CDI prevention) must be addressed by identifying and exploring common, unique, and conflicting work system barriers and facilitators across those individuals and groups affected by the intervention. Such factors must be addressed in the continuous implementation of clinical interventions.28 Considerations for workers other than those providing clinical care, whose work also affects or is affected by the intervention, must also be addressed. These different stakeholders will gain from a greater understanding of how their work affects the role and responsibilities of others that must function in the same work system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality through by grant number R03HSO023791 supported this work. Support for this publication was provided partly by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR002373. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

There is no conflict of interest to declare for any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 2015;372:825–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucado J, Gould C, Elixhauser A. Clostridium Difficile Infections (CDI) in Hospital Stays, 2009: Statistical Brief #124 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss K, Boisvert A, Chagnon M, et al. Multipronged intervention strategy to control an outbreak of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and its impact on the rates of CDI from 2002 to 2007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans ME, Kralovic SM, Simbartl LA, Jain R, Roselle GA. Effect of a Clostridium difficile Infection Prevention Initiative in Veterans Affairs Acute Care Facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016;37:720–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:e1–e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ngam C, Hundt AS, Haun N, Carayon P, Stevens L, Safdar N. Barriers and facilitators to Clostridium difficile infection prevention: A nursing perspective. American Journal of Infection Control 2017;45:1363–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hundt AS, Ngam C, Carayon P, Haun N, Safdar N. Work system barriers and facilitators to compliance with infection prevention intervention: Initial findings regarding hand hygiene from three target roles. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the HFES 60th Annual Meeting 2016; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yanke E, Moriarty H, Carayon P, Safdar N. A qualitative, interprofessional analysis of barriers to and facilitators of implementation of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Clostridium difficile prevention bundle using a human factors engineering approach. Am J Infect Control 2018;46:276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie A, Carayon P, Cartmill R, et al. Multi-stakeholder collaboration in the redesign of family-centered rounds process. Applied Ergonomics 2015;46:115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie A, Carayon P, Cox ED, et al. Application of participatory ergonomics to the redesign of the family-centred rounds process. Ergonomics 2015;58:1726–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Detienne F Collaborative design: Managing task interdependencies and mulitiple perspectives. Interacting with Computers 2006;18:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MJ, Carayon-Sainfort P. A balance theory of job design for stress reduction. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 1989;4:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith MJ, Carayon P. Balance theory of job design In: Karowski W, ed. International Encyclopedia of Ergonomics and Human Factors. London: Taylor & Francis; 2001:1181–1184. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carayon P, Hundt AS, Karsh B-T, et al. Work system design for patient safety: The SEIPS model. Quality & Safety in Health Care 2006;15 (Supplement I):i50–i58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanke E, Carayon P, Safdar N. Translating evidence into practice using a systems engineering framework for infection prevention. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 2016;35:1176–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel PR, Kallen AJ. Human factors and systems engineering: The future of infection prevention? Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 2018;39:849–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Wachter RM, et al. Advancing the science of patient safety. Ann Intern Med;154:693–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giorgi A The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 2012;43:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown KA, Mitchell TR. Performance obstacles for direct and indirect labour in high technology manufacturing. International Journal of Production Research 1988;26:1819–1832. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carayon P, Gurses AP, Hundt AS, Ayoub P, Alvarado CJ. Performance obstacles and facilitators of healthcare providers In: Korunka C, Hoffmann P, eds. Change and Quality in Human Service Work. Mering, Germany: Rainer Hampp Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robson C Real World Research. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishig; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan DJ, Pineles L, Shardell M, et al. The effect of contact precautions on healthcare worker activity in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;34:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tschudin-Sutter S, Lucet JC, Mutters NT, Tacconelli E, Zahar JR, Harbarth S. Contact Precautions for Preventing Nosocomial Transmission of Extended-Spectrum β Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli: A Point/Counterpoint Review. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin EM, Bryant B, Grogan TR, et al. Noninfectious Hospital Adverse Events Decline After Elimination of Contact Precautions for MRSA and VRE. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2018;39:788–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartley JM, Olmsted RN, Haas J. Current views of health care design and construction: practical implications for safer, cleaner environments. Am J Infect Control 2010;38:S1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilcox MH, Planche T, Fang FC, Gilligan P. What is the current role of algorithmic approaches for diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection? J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:4347–4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musuuza JS, Roberts TJ, Carayon P, Safdar N. Assessing the sustainability of daily chlorhexidine bathing in the intensive care unit of a Veteran’s Hospital by examining nurses’ perspectives and experiences. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carayon P Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Appl Ergon 2006;37:525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]