Abstract

Neurotropic and neuroinvasive capabilities of coronaviruses have been described in humans. Neurological problems found in patients with coronavirus infection include: febrile seizures, convulsions, loss of consciousness, encephalomyelitis, and encephalitis. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is caused by SARS-CoV2. In severe cases, patients may develop severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and acute cardiac injury. While seizures and status epilepticus have not been widely reported in the past five months since the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, patients with COVID-19 may have hypoxia, multiorgan failure, and severe metabolic and electrolyte disarrangements; hence, it is plausible to expect clinical or subclinical acute symptomatic seizures to happen in these patients. One should be prepared to treat seizures appropriately, if they happen in a patient who is already in a critical medical condition and suffers from organ failure.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Seizure, COVID-19, Coronavirus

1. Introduction

Coronavirus is one of the major viruses that primarily targets the human respiratory system. Previous outbreaks of coronaviruses include the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012. The most recent pandemic of coronavirus infection is coronavirus disease (COVID-19) that is caused by SARS-CoV2; it is the causative agent of a potentially fatal disease [1]. The symptoms of COVID-19 infection appear after an incubation period of about five days. The most common symptoms at the onset of COVID-19 illness are fever, cough, and fatigue; other symptoms include sputum production, headache, hemoptysis, diarrhea, and dyspnea. In severe cases, patients may develop severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, organ failure, and acute cardiac injury [1]. The first cases were reported in December 2019 [1]; however, when the MEDLINE (accessed from PubMed) was searched, from inception to May 3, 2020, with the key word “COVID 19”, surprisingly 8767 articles were yielded. This shows that COVID-19 pandemic is of great global public health concern.

2. Neurological manifestations of coronavirus infections

Coronaviruses have been associated with neurological manifestations in patients with respiratory tract infections [2]. Neurotropic and neuroinvasive capabilities of coronaviruses have been described in humans. Upon nasal infection, coronavirus enters the central nervous system (CNS) through the olfactory bulb, causing inflammation and demyelination. Once the infection is set, the virus can reach the whole brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in less than seven days [2]. Neurological problems found in patients with coronavirus infection include: febrile seizures, convulsions, change in mental status, encephalomyelitis, and encephalitis [2]. In this narrative review, the evidence on the occurrence and management of seizures in patients with various coronavirus (CoV) infections will be discussed.

2.1. SARS and seizures

The first case of SARS-CoV infection with neurological manifestations was reported in 2003; the patient had seizures [3]. Another patient with SARS and seizures has been reported later in the literature [4]. In these two patients, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tested positive for SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) [3, 4].

In a more recent study, among 183 hospitalized children with clinically suspected acute encephalitis, 22 (12%) had coronavirus infection (type was not specified) by detection of anti-CoV IgM. Five of these 22 patients (23%) had seizures. Cerebrospinal fluid was analyzed in all patients with coronavirus-associated encephalitis; 10 patients (45.5%) had CSF pleocytosis. Three of the 22 patients with coronavirus-associated encephalitis underwent electroencephalography (EEG); all three results were normal [5].

2.2. MERS and seizures

In one study of 70 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV infection, six people (8.6%) had seizures and altered mental status was reported in 26% of the patients (18 patients) [6]. MERS-CoV infection is a serious disease that may affect multiple organs and may cause pulmonary, renal, hematological, gastrointestinal, and neurological (e.g., seizures, intracerebral hemorrhage, etc.) complications [6,7].

Furthermore, there are reports of seizures associated with other types of coronavirus infection [8]. In one study of viral etiological causes of febrile seizures for respiratory pathogens in 174 children, in patients younger than 12 months, CoV−OC43 was the most common etiology [9]. In addition, in young children, CoV-HKU1 infection is also associated with febrile seizures [10].

2.3. COVID-19 and seizures

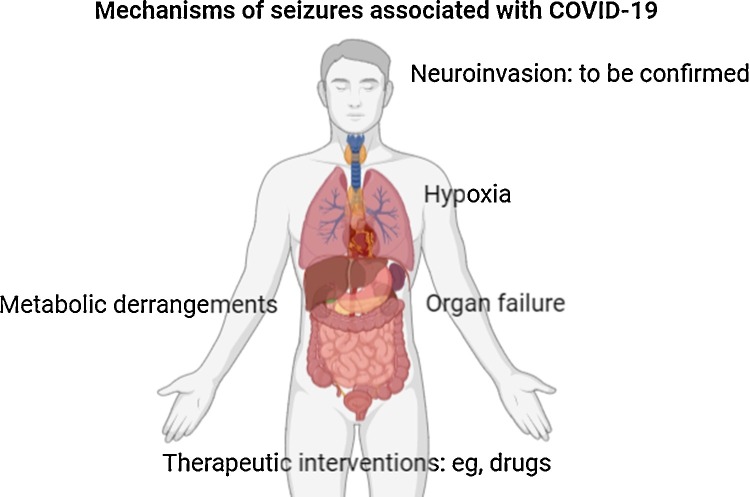

Coronaviruses, which are large enveloped non‐segmented positive‐sense RNA viruses, generally cause enteric and respiratory diseases in animals and humans [11]. Most coronaviruses share a similar viral structure and infection pathway; therefore, the infection mechanisms previously found for other coronaviruses may also be applicable for SARS‐CoV2. A growing body of evidence shows that neurotropism is one common feature of coronaviruses [2,[11]. One study, specifically investigated the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and could document CNS manifestations in 25% of the patients [headache (13%), dizziness (17%), impaired consciousness (8%), acute cerebrovascular problems (3%), ataxia (0.5), and seizures (0.5%)] [12]. There is also a report of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-CoV2 accompanied by seizures (SARS-CoV2 RNA was detected in the CSF) [13]. Another report describes a patient affected by COVID-19 whose primary presentation was a focal status epilepticus [14]. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that some patients with COVID-19 develop seizures as a consequence of hypoxia, metabolic derangements, organ failure, or even cerebral damage that may happen in people with COVID-19 (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of seizures in patients with COVID-19.

3. Management of seizures

Seizures may happen as a result of an acute systemic illness, a primary neurological pathology, or a medication adverse-effect in critically ill patients and can present in a wide array of symptoms from convulsive activity, subtle twitching, to lethargy [15]. In critically ill patients, untreated isolated seizures can quickly escalate to generalized convulsive status epilepticus or, more frequently, nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), which is associated with a high morbidity and mortality [15].

When visiting a patient who is in a critical medical condition and has a change in mental status, it is suggested to make sure that NCSE is not a part of the clinical scenario [16,17]. Salzburg Consensus Criteria for Non-Convulsive Status Epilepticus is a helpful guide to make a diagnosis of NCSE in critically ill patients [18]. If a patient with COVID-19 develops a clinical or subclinical seizure or status epilepticus, it is very reasonable to start the treatment urgently [19]. In such circumstances, one should try to determine the cause of the seizure and manage the cause [e.g., hypoxia, fever (in children), metabolic derangements, etc.] immediately. However, it is often necessary to start antiseizure medication (ASM) therapy as well; this is to abort prolonged seizures and also to prevent further seizures from happening.

When an ASM is initiated, drug factors, such as the onset of action, drug interactions, and adverse effects, and also patient factors, such as age, respiratory, renal, hepatic, and cardiac functions, should be taken into account [20]. Below, is a summary of different scenarios of seizure management in patients, who are critically ill with COVID-19.

3.1. A single seizure less than 5 min long

There is no need for rescue treatment with benzodiazepines (these drugs should be used with caution in patients with compromised respiratory function), but an ASM should be started to prevent further seizures from happening. Since these patients are critically ill, a drug with intravenous (IV) formulation is preferable. However, because these patients suffer from severe respiratory and/or cardiac problems, drugs with significant respiratory/cardiac adverse effects (e.g., Phenytoin, Phenobarbital, etc.) should be prescribed cautiously, with clinical monitoring as appropriate. In addition, drugs with significant drug interactions (e.g., Carbamazepine, Phenytoin, Phenobarbital, and Valproic acid) should be prescribed cautiously [20]. Furthermore, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which may become necessary in the management of patients with COVID-19 and severe pneumonia [21], can impact the pharmacokinetics of highly protein-bound drugs (e.g., Phenytoin and Valproic acid) [20]. Lacosamide should be used with caution in patients with cardiac conduction problems (e.g., marked first-degree AV block, second-degree or higher AV block), on concomitant medications that prolong PR interval, or with severe cardiac disease such as myocardial ischemia or heart failure [22]. Lacosamide use is not recommended in patients with severe hepatic impairment. However, if cardiac impairment or severe hepatic impairment does not exist in a patient with COVID-19, it is a reasonable ASM [23]. Brivaracetam is a safe treatment option in these patients. Dosage adjustment is recommended for all stages of hepatic impairment [24]. Similarly, levetiracetam is an optimal ASM in critically ill patients with a reasonable adverse effect profile and minimal interactions with other drugs. Dosage adjustment is necessary in patients with renal impairment [23].

3.2. More than one seizures (either shorter or longer than 5 min) or status epilepticus (convulsive or nonconvulsive)

General management principals of serial seizures and status epilepticus should be applied. Rescue treatment (with benzodiazepines) and an ASM should be started to abort the seizure and to prevent further seizures from happening [16,20,23].

In any of the above scenarios, a thorough investigation of the underlying cause of the seizure should be performed immediately and an appropriate treatment strategy to resolve that cause should be implemented. New-onset seizures in these patients could be considered as acute symptomatic seizures. Patients with acute symptomatic seizures do not need long-term ASM therapy after the period of acute illness, unless a subsequent seizure occurs [25]. Since the period from the onset of COVID-19 symptoms to death may range from 6 to 41 days [1], it is reasonable to continue the ASM for about 6 weeks and then tapper and discontinue the drug rapidly in 1–2 weeks.

4. COVID-19 in people with epilepsy

Another important issue is the potential risks associated with COVID-19 in people with epilepsy (PWE). This issue is so important that it deserves a full manuscript, which is beyond the scope of the current work. There are many questions on this topic, which should be answered and clarified. The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) has provided valuable resources to tackle some of the important issues on this topic [26]. There is also a valuable review by Dr. French and colleagues on “Keeping people with epilepsy safe during the COVID-19 pandemic” [27]. Here, some examples of the issues of COVID-19 in PWE are provided:

4.1. How should the management be altered during the COVID-19 pandemic in PWE?

Drug-drug interactions between ASMs and anti-COVID therapies may pose significant challenges. Furthermore, cardiac, hepatic or renal impairments, which may happen in patients with severe COVID-19, may require adjustment to ASMs. Finally, adverse effects of both groups of therapies (ASMs and anti-COVID therapies) should be considered. For example, lacosamide prolongs the PR interval and hydroxychloroquine (a drug that is suggested to be helpful in treating COVID-19) prolongs the QT interval in electrocardiogram (ECG) [28]. Therefore, administering hydroxychloroquine to a patient with epilepsy, who is already taking lacosamide, may carry an added risk and should be done with precaution and ECG monitoring. Also, QT prolongations may occur with azithromycin and chloroquine and some ASMs (e.g., carbamazepine, lacosamide, phenytoin, and rufinamide) may cause cardiac conduction abnormalities. Co-administration of these two groups of drugs should be done cautiously, with ECG monitoring as appropriate [29,30].

4.2. Have there been issues with access to ASMs during the pandemic?

A study of 227 patients with epilepsy during the SARS outbreak in 2003 in Taiwan, showed that 22% of the people did not receive their medications due to loss of contact with their healthcare providers; 12% of the patients suffered seizure control status worsening during the outbreak (including two patients with status epilepticus) [31]. This should be investigated in the context of the current pandemic.

4.3. Should telemedicine be stepped up, or initiated?

In the context of a pandemic, telemedicine, particularly video consultations, should be promoted and scaled up to reduce the risk of transmission [32]. Telemedicine has been shown to improve access to specialized care for patients with epilepsy in difficult circumstances (e.g., living in rural areas) in previous studies [33]. However, many countries do not have a regulatory framework to authorize, integrate, and reimburse telemedicine services, including during outbreaks [32]. For countries without integrated telemedicine in their national healthcare system, the COVID-19 pandemic is a call to adopt the required regulatory frameworks for supporting wide adoption of telemedicine [32].

5. Conclusion

While seizures and status epilepticus have not been addressed appropriately in the past five months since the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, patients with COVID-19 may have hypoxia, multiorgan failure, and severe metabolic and electrolyte disarrangements; hence, it is plausible to expect clinical or subclinical acute symptomatic seizures to happen in these patients. One should be prepared to treat seizures appropriately, if they happen in a patient who is already in a critical medical condition. Detailed clinical, neurological, and electrophysiological investigations of the patients (particularly those with a change in mental status), and attempts to isolate SARS-CoV-2 from CSF may clarify the roles played by this virus in causing seizures.

Disclosures

Ali A. Asadi-Pooya, M.D.: Honoraria from Cobel Daruo, RaymandRad and Tekaje; Royalty: Oxford University Press (Book publication).

Acknowledgment

This was a non-funded study.

References

- 1.Rothan H.A., Byrareddy S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;26(Febuary) doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohmwald K., Gálvez N.M.S., Ríos M., Kalergis A.M. Neurologic alterations due to respiratory virus infections. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:386. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung Ec, Chim Ss, Chan Pk, Tong Yk, Ng Ek, Chiu Rw, et al. Detection of SARS coronavirus RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Chem. 2003;49:2108–2109. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.025437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau K.K., Yu WC Chu C.M., Lau S.T., Sheng B., Yuen K.Y. Possible central nervous system infection by SARS coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:342–344. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y., Li H., Fan R., Wen B., Zhang J., Cao X., et al. Coronavirus infections in the central nervous system and respiratory tract show distinct features in hospitalized children. Intervirology. 2016;59:163–169. doi: 10.1159/000453066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saad M., Omrani A.S., Baig K., Bahloul A., Elzein F., Matin M.A., et al. Clinical aspects and outcomes of 70 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a single-center experience in Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Algahtani H., Subahi A., Shirah B. Neurological complications of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3502683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez S.R., Robinson C.C., Holmes K.V. Detection of four human coronaviruses in respiratory infections in children: a one-year study in Colorado. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1597–1604. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carman K.B., Calik M., Karal Y., Isikay S., Kocak O., Ozcelik A., et al. Viral etiological causes of febrile seizures for respiratory pathogens (EFES Study) Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:496–502. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1526588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woo P.C., Yuen K.Y., Lau S.K. Epidemiology of coronavirus-associated respiratory tract infections and the role of rapid diagnostic tests: a prospective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18(Suppl 2):22–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y.C., Bai W.Z., Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may be at least partially responsible for the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;27(Febuary) doi: 10.1002/jmv.25728. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mao L., Wang M., Chen S., et al. Neurological Manifestations of hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. JAMA Neurol. 2020;10(April) doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriguchi T., Harii N., Goto J., et al. A first case of Meningitis/Encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;(20 April):30195–30198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [Epub ahead of print]. 3. pii: S1201-S9712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vollono C., Rollo E., Romozzi M., et al. Focal status epilepticus as unique clinical feature of COVID-19: a case report. Seizure. 2020;78:109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ch’ang J., Claassen J. Seizures in the critically ill. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;141:507–529. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63599-0.00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutter R., Semmlack S., Kaplan P.W. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in adults - insights into the invisible. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:281–293. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Máñez Miró J.U., Díaz de Terán F.J., Alonso Singer P., Aguilar-Amat Prior M.J. Emergency electroencephalogram: usefulness in the diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus by the on-call neurologist. Neurologia. 2018;33:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leitinger M., Beniczky S., Rohracher A., Gardella E., Kalss G., Qerama E., et al. Salzburg consensus criteria for non-convulsive status epilepticus--approach to clinical application. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell J.S., Colangeli R., Wolff M.D., Wall A.K., Phillips T.J., George A., et al. Postictal hypoperfusion/hypoxia provides the foundation for a unified theory of seizure-induced brain abnormalities and behavioral dysfunction. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1493–1501. doi: 10.1111/epi.13827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrokh S., Tahsili-Fahadan P., Ritzl E.K., Lewin J.J., 3rd., Mirski M.A. Antiepileptic drugs in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2018;22:153. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2066-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan. China. JAMA. 2020;7(Febuary) doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lachuer C., Corny J.2, Bézie Y., Ferchichi S., Durand-Gasselin B. Complete atrioventricular block in an elderly patient treated with low-dose lacosamide. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2018;18:579–582. doi: 10.1007/s12012-018-9467-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trinka E., Kälviäinen R. 25 years of advances in the definition, classification and treatment of status epilepticus. Seizure. 2017;44:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brigo F., Lattanzi S., Nardone R., Trinka E. Intravenous brivaracetam in the treatment of status epilepticus: a systematic review. CNS Drugs. 2019;33:771–781. doi: 10.1007/s40263-019-00652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergey G.K. Management of a first seizure. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(1 Epilepsy):38–50. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.https://www.ilae.org/patient-care/covid-19-and-epilepsy/ accessed on April 14, 2020.

- 27.French J.A., Brodie M.J., Caraballo R., et al. Keeping people with epilepsy safe during the Covid-19 pandemic. Neurology. 2020;23(April) doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009632. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009632. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009632. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.https://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB06218/ accessed on April 14, 2020.

- 29.Wu C.I., Postema P.G., Arbelo E., et al. SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 and inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 2020;31(March) doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.03.024. [Epub ahead of print] pii: S1547-5271(20)30285-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auerbach D.S., Biton Y., Polonsky B., et al. Risk of cardiac events in Long QT syndrome patients when taking antiseizure medications. Transl Res. 2018;191:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.10.002. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai S.L., Hsu M.T., Chen S.S. The impact of SARS on epilepsy: the experience of drug withdrawal in epileptic patients. Seizure. 2005;14:557–561. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohannessian R., Duong T.A., Odone A. Global telemedicine implementation and integration within health systems to fight the COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6 doi: 10.2196/18810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haddad N.1, Grant I., Eswaran H. Telemedicine for patients with epilepsy: a pilot experience. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;44:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]