Abstract

Background:

Promoting health literacy in early life is regarded as an important means of sustaining health literacy and health over the life course. However, little evidence is available on children's health literacy, partly due to a scarcity of suitable measurement tools. Although there are 18 tools to measure specific items of health literacy for people younger than age 13 years, there is a lack of comparable, valid, and age-appropriate measures of generic health literacy.

Objective:

This study aimed to develop and qualitatively test an age-adapted version of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q) for German-speaking children age 9 and 10 years. Although validated for adults and adolescents, the HLS-EU-Q has never been age-adapted or used with children.

Methods:

The content and language of HLS-EU-Q items were adapted for this age range. The literature was consulted to inform this process, and adaptations were developed and selected based on consensus among authors. From an item pool of 102 adapted items, 37 were given to 30 fourth-grade students in a cognitive pretest, which is a standard procedure in questionnaire development aiming to explore how items are interpreted. Participants (18 girls, 12 boys) were mostly age 9 or 10 years (range, 9–11 years).

Key Results:

Problems with misinterpretation were identified for some items and participants (e.g., items designed to assess participants' perceived difficulty in accessing and appraising health information were partly answered on the basis of knowledge and experience). A final selection of 26 well-performing items corresponded to the underlying HLS-EU-Q framework.

Conclusions:

This is the first age-adapted version of the HLS-EU-Q. A preliminary 26-item questionnaire was successfully developed that performed well in a cognitive pretest. However, further research needs to verify its validity and reliability. The present findings help to advance the measurement of generic self-reported health literacy in children and highlight the need for cognitive pretesting as an essential part of questionnaire development. [HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice. 2020;4(2):e119–e128.]

Plain Language Summary:

The European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire is used for testing adults' health literacy. It was adapted for German-speaking children age 9 and 10 years. Based on a review of the original items and the literature, 26 questionnaire items were developed and tested in interviews with 30 children. Although problems with understanding could be identified, the questionnaire was mostly well understood.

Both researchers and policymakers agree on the importance of promoting health literacy at an early age for empowerment, long-term health, and quality of life throughout the life course (Borzekowski, 2009; Public Health England, 2015). In particular, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized health literacy as “a critical determinant of health,” stating that health literacy “must be an integral part of the skills and competencies developed over a lifetime, first and foremost through the school curriculum.” (World Health Organization, 2017, p. 8) Such propositions, which may potentially determine the kind of skills conveyed to young people and how these are conveyed through the school system, need to be based on solid evidence. However, at present, there are hardly any reliable or comparable data on the development and distribution of children's health literacy in different age groups, settings, and countries (Okan et al., 2018).

Measuring Children's Health Literacy: State of Research

Three systematic reviews (Guo et al., 2018; Okan et al., 2018; Ormshaw, Paakkari, & Kannas, 2013) have identified 18 measurement tools used to study health literacy in children (defined here as people younger than age 13 years). These tools differ greatly because they cover a broad range of measurement approaches (self-report, performance test, mixed), of components of health literacy (health knowledge, health-related beliefs, communication, self-management, critical thinking, access to health information, service navigation), and of health areas (general health, oral health, mental health, diabetes, nutrition) (Bollweg & Okan, 2019). Even those tools designed to measure “general” or “generic” health literacy (i.e., health literacy that is not specific for certain diseases or health areas) are hardly comparable due to their focus on different components or topics. Some are tailored for a narrow age range, whereas others were designed originally for adults but are applied to children without any age-related adaptation. Furthermore, some of the identified measurement tools either lack or fail to report any assessment of psychometric properties (Bollweg & Okan, 2019). Hence, there is a need for comparable and validated tools designed to assess health literacy in specific age groups. This applies particularly to Germany, because only two of the identified measurement tools are available in German (Schmidt et al., 2010; Wallmann, Gierschner, & Froböse, 2012). This study addresses this research gap by developing and testing a measurement tool to assess generic health literacy in fourth-grade elementary school children in Germany.

Adapting the HLS-EU-Q: Rationale and Challenges

We chose the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q) (Sørensen et al., 2013) as the starting point for questionnaire development because its validity and reliability been confirmed in a range of studies in different countries and different settings (Amoah, Phillips, Gyasi, Koduah, & Edusei, 2017; Duong et al., 2017; Nakayama et al., 2015; Pelikan & Ganahl, 2017; Sørensen et al., 2015; Toçi, Burazeri, Sørensen, Kamberi, & Brand, 2015). Furthermore, it is built on a comprehensive definition of generic health literacy that goes beyond health care navigation and addresses how people use health information in everyday life (Sørensen et al., 2012). Moreover, a German adaptation of the HLS-EUQ was already available at the start of this study. Although used with adults and even adolescents, the HLS-EU-Q has never been used with children (Pelikan & Ganahl, 2017). In the interest of comparability and of assessing health literacy across the lifespan, it seems particularly useful to adapt this measurement tool for a younger age group. Although children might have only a limited ability to make their own health-related decisions, assessing health literacy at an early age will make it possible to explore both the emergence of disparities in health literacy and the determinants of health literacy in childhood.

Nonetheless, several critical aspects emerge when adapting the HLS-EU-Q for children. First, it was developed for adults and addresses health-related topics that might not be relevant in children's everyday lives; thus, content-wise adaptations might be necessary. These could relate to, for example, age-specific disease patterns, aspects of dependency, or limited participation in health-related decision making (Okan, Bröder, Pinheiro, & Bauer, 2017). Second, the HLSEU-Q might be too difficult for fourth-grade students to understand. A study of 14- to 17-year-old adolescents, for instance, revealed that some terms in the questionnaire were not well understood or were even misinterpreted (Domanska et al., 2018). Such problems can be expected to be even more prevalent in younger age groups. Accordingly, extensive adaptations of language and item complexity are necessary to ensure the appropriateness of the questionnaire for children age 9 and 10 years.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a questionnaire development study to adapt and test HLS-EU-Q items. We carried out two phases of cognitive pretesting to guide the item adaptation and to test its comprehensibility. We also conducted a subsequent quantitative validation study that is reported elsewhere (Bollweg et al., in press).

Using the HLS-EU-Q

The HLS-EU-Q assesses participants' perceived difficulty in accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying health information in the contexts of health care, disease prevention, and health promotion. Thus, the questionnaire is not a performance test, but assesses “subjective health literacy” or “self-reported health literacy.” The HLS-EU-Q has been used in different versions with varying numbers of items, although the 47-item version is in most common use (Pelikan & Ganahl, 2017). We retained the original HLS-EU-Q item format and response categories; hence, each item is phrased: “How easy or difficult is it for you to . . . ?” and answered on 4-point scales ranging from 1 (very difficult) to 4 (very easy). The HLS-EU-Q is usually administered as a (computer-assisted) personal interview using the aforementioned four response options along with a “don't know” option if participants express this response (Sørensen et al., 2013). In this study, we used the HLS-EU-Q in a paper-and-pencil format and provided “don't know” as an additional response category to avoid arbitrary or unidentified missing responses. We also tested an alternative item format using statements (e.g., “It is easy for me to understand . . .”) and a 5-point agreement scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (absolutely true).

Item Adaptation

We assessed the adaptability of all HLS-EU-Q47 items by examining their content and language. To determine the appropriateness of each item's content, we examined German health reporting and health-related studies. Specifically, we collected information on diseases prevalent among 9- and 10-year-old children, on vaccination status, interactions with health care professionals, medication intake, body perception, and school-related stress. Based on this information, we evaluated whether the items address topics that are important for children's health in the given age group (e.g., a “cold” instead of “high blood pressure”). To rate the appropriateness of each item's language, we screened the literature on child research and the recommendations on item development in certain age groups. We also consulted existing questionnaires used with children in other studies and used this information to further inform the adaptation of HLS-EU-Q items to develop items with a language and grammatical structure that are easier to understand, more concrete, and simpler than that in the original items. However, it was also important to preserve the meaning of the original items and the inherent structure of the questionnaire (accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying health information in the contexts of health care, disease prevention, and health promotion).

We developed adaptations for each HLS-EU-Q item, and three researchers (T.M.B., O.O., P.P.) compared the content, language, and fit of the adapted items with the underlying model (Sørensen et al., 2012). We selected items for each phase of the cognitive pretest, and these items were subsequently re-evaluated and modified. We made our final selection of items after the second cognitive pretest. Decisions were based on a consensus among all authors whose research backgrounds covered education, medicine, public health, sociology, psychology, and epidemiology.

We embedded the adapted health literacy items in a broader questionnaire that we developed simultaneously. Table A presents the different item areas of the overall questionnaire. This article focuses only on the development of the health literacy scale.

Table A.

Topics Assessed in the “Overall Questionnaire” (N = 116 items)

| Area | Number of Items | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Sources of health information | 9 | How much do you learn about health from? |

| Seal-reported health literacy | 26 | How easy or difficult is it for you to eat healthy? |

| Dealing with health information | 4 | When you hear something about health, how often do you ask yourself if it is true? |

| Age, sex, language spoken at home, family affluence | 11 | What language do you speak to your mother most of the time? How many bathrooms are there at home? |

| Parental health orientation | 3 | My parents make sure that I eat healthy. |

| Parental health behavior | 2 | How often does your father work out? |

| Health autonomy | 2 | I decide on my own how many sweets I eat. |

| Health knowledge | 5 | If the label on a drink states “less calories,” is it healthy? |

| Functional health literacy | 15 | Cloze deletion test for reading and a numeracy test. |

| Health behavior | 4 | How many times a day do you brush your teeth? |

| Cultural capital | 3 | How often do you go to a museum or to an exhibition? |

| Attitudes | 5 | I can do a lot to become a healthy adult. |

| Self-efficacy | 3 | I can find a solution to most problems. |

| Self-reported health status | 4 | How healthy are you? |

| Milieu-related attitudes | 14 | Everybody should have the same opportunities in life. |

| Other | 6 | Please write down the time. |

Sample

A convenience sample of 30 children attending 4th grade (age 9 to 11 years) was recruited from two elementary schools in a northern German city. We chose fourth-grade students for this study because in most German federal states, this is the last year before students are allocated to different school tracks. Hence, we could assume that the influence of the school system on the development of students' skills and knowledge in relation to health literacy would still be comparable, because different school tracks had not yet started to influence the acquisition and development of health literacy. Moreover, we could expect children of this age to have sufficiently developed language skills to participate in a written standardized survey.

Cognitive Pretests

Cognitive interviewing, or cognitive pretesting, is a method commonly used in questionnaire development “to understand how respondents perceive and interpret questions and to identify potential problems that may arise” when using a newly developed questionnaire (Drennan, 2003, p. 57). To verify the comprehensibility of adapted health literacy items, we conducted two cognitive pretests in June and September of 2016. To gain in-depth feedback on a broad range of items, we conducted two phases instead of testing a final selection of items in only one session. In both pretests, participants filled in the questionnaire and were interviewed face-to-face using both general and specific probing questions. General probing questions were, for example, “Did you know right away how to fill out the questionnaire?” or “Was there anything you didn't understand?” (all questions were posed and answered in German; the original German versions of these translations are available from the authors on request). Specific probing questions were related to individual items. For instance, the item “. . . how easy or difficult is it for you to understand why you sometimes need to see the doctor even though you are not ill?” was accompanied by the questions “Did any of you ever need to go to the doctor even though you weren't ill? Why did you need to go?” All interviews were audiotaped and analyzed anonymously. Interviews were conducted by trained staff employed by the cooperation partner responsible for data collection, the Social Sciences Service Centre SUZ (Duisburg, Germany). SUZ staff compiled findings from cognitive interviews in a report that not only summarized individual feedback on specific items but also gave an overall assessment of the performance of the questionnaire.

In the first phase of the cognitive pretest, we gave two different sets of adapted HLS-EU-Q items (12 items, and 13 items, respectively) to three girls and three boys age 9 and 10 years in one-on-one interviews (n = 6 in total). We used only the alternative item format in this phase (items formulated as statements with corresponding agreement scale).

Twenty-four participants age 9 to 11 years (15 girls, 9 boys) took part in the second cognitive pretest. In this phase, 24 health literacy items were tested, consisting of 12 well-performing items from the first phase and 12 further items from the item pool. All 24 items were tested in both item formats (original and alternative, 48 items total). We gave 12 of these items to each of four groups of six participants. In this pretest phase, we examined not only health literacy items but also the complete questionnaire (116 items). Due to time constraints, cognitive interviews were also conducted with groups of six children.

Ethics Approval, Consent for Participation, and Funding

This study was approved by the Bielefeld University Ethics Board (Reference No 2016-141-R), as well as the University Data Protection Officer. Parents or legal guardians provided informed written consent for all participants. Participation was voluntary and participants were informed that all information would be treated with full confidentiality. No incentives were used. This work was carried out within the Health Literacy in Childhood and Adolescence (HLCA) Consortium (www.hlca-consortium.com), funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Results

Item Development

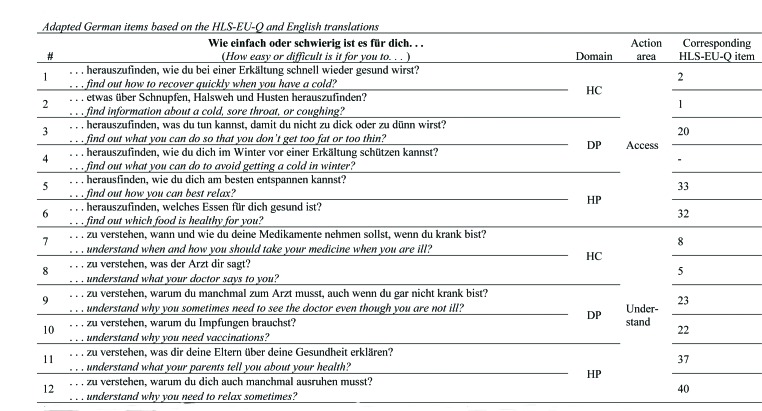

We adapted HLS-EU-Q items to better reflect children's health-related experience. We will illustrate this process with two examples: First, based on the fact that a common cold is among the most prevalent diseases in 7- to 10-year-old children (Kamtsiuris, Atzpodien, Ellert, Schlack, & Schlaud, 2007), we changed the item “. . . find information on treatments of illnesses that concern you?” (HLS-EU-Q item 1) to “. . . find information on how to recover quickly when you have a cold?” (all German-language items used in the test are reported in Table A). Second, the literature reports that a significant proportion of 11-year-old children in Germany consider themselves to be “too fat” or “too skinny” (HBSC-Studienverbund Deutschland, 2015). Thus, the item “. . . find information on how to prevent or manage conditions like being overweight, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol?” (HLS-EU-Q item 20) was changed to “. . . find out what you can do so that you don't get too fat or too skinny.” All items were adapted in a similar manner to better reflect health areas relevant for children of this age while preserving the original meaning of the item.

The literature reveals only rather vague recommendations and no concrete evidence on language, item complexity, and wording (Vogl, 2012). Comparisons with other questionnaires for 9- and 10-year-old children showed that common practice is to use short and concise items and hardly any conditional clauses (cf. Rees & Main, 2015). Accordingly, we aimed for short and concise items. However, the HLS-EU-Q uses a rather wordy format (“On a scale from very easy to very difficult, how easy would you say it is to . . .”), which is why items could be shortened only to a limited extent.

Several alternative adaptations were developed for most HLS-EU-Q items, and the initial item pool consisted of 102 items. The best adaptation for each item was chosen, aiming for an optimal trade-off between congruence with the original item, target group relevance, and easy language. It needs to be noted, however, that the development of items that address the perceived difficulty of appraising health information was particularly challenging because no data were available on specific instances in which children perform such tasks.

Cognitive Pretest

First Phase

Filling in the questionnaires took between 4 and 9 minutes, and consecutive cognitive interviews took between 16 and 33 minutes. Overall, it was easy for participants to fill in the questionnaire, and interviewers noted that the interviewed children's reading ability seemed adequate for the questionnaire content. Some participants were familiar with filling in questionnaires, but those who lacked such familiarity were able to understand the questionnaire instructions. The alternative response format (statements and 5-point agreement scale) was well understood, with all response categories being used. Children reported that it was easy for them to choose an answer, but that they sometimes had to recall memories of specific situations to reply to an item. The structure and layout of the questionnaire were rated positively.

However, specific probing revealed that some items were not understood as intended. For instance, participants were asked to elaborate on their response to the item “It is easy for me to find out how to recover quickly when I have a cold.” One participant responded with “my mother usually makes chicken soup for me when I have a cold”; another participant responded “sometimes I know right away, sometimes I don't”; and a third respondent replied by saying “I would ask the doctor first, because he's informed best. Sometimes, I also look up things on the Internet or ask my parents” (all statements were translated from German by the authors). In two of three cases, the term “to find out” was not reflected in the respective responses, implying that these children considered important parts of the item (“recover from a cold”), but also neglected other important parts (“to find out”). This phenomenon was observed in 12 of 25 items. Specifically, items assessing the perceived difficulty of accessing and appraising health information were often misinterpreted as items about knowledge and habits. Nonetheless, one-half of the items (13 of 25) were interpreted as intended. For example, the item “I understand when and how to take my medicine” was commented on with “the doctor prescribed the medicine and told me when to take it. When the doctor tells me to take one in the morning, I'll do that when I wake up.”

Second Phase

In the second pretest phase, filling in the questionnaire (116 items) took between 22 and 45 minutes, and the subsequent group interviews took between 31 and 45 minutes. It was observed that the group of participants was more heterogeneous in this pretest, and two participants were unable to finish the questionnaire within one “school hour” (i.e, 45 minutes). Again, the structure and layout of the questionnaire were rated positively, and most items were understood as intended. For instance, the item “. . . to understand what the doctor tells you” was commented on with “difficult . . . doctors talk so quickly,” or “I don't get anything, I can't understand that language.” However, once again, we found that some items were not interpreted as intended. For instance, the item “. . . to find out what you can do so you don't get too fat or too skinny” was commented with “I know what I need to do so I don't get too fat: exercise a lot, eat healthy.” As this example illustrates, the aspect of “finding out” or “accessing information” was not reflected in the participant's comment. This was the case for some participants whose answers were based on their knowledge and experience regarding the tasks or situations described in each item rather than on the processes of accessing, understanding, appraising, or applying health information.

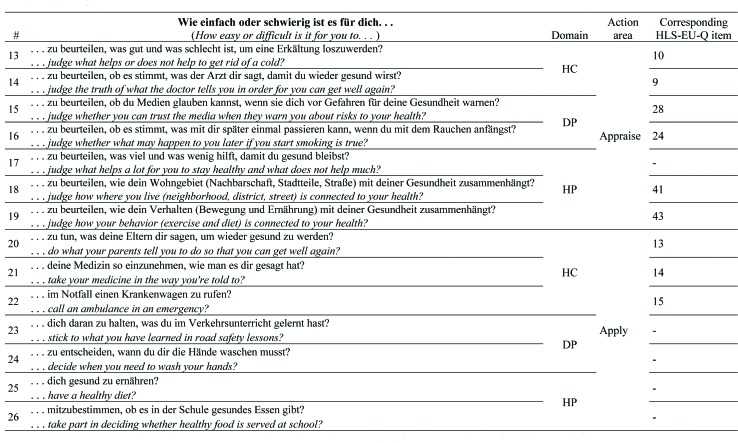

We revised the items and made a final selection of 26 items that performed best in the cognitive pretests and mirror the different action areas and health domains of the HLS-EU definition of health literacy. This means that we also included items addressing the perceived difficulty in accessing and appraising information, although we identified these domains as being prone to misinterpretation for some participants. Nonetheless, they were included to allow for statistical analyses in a subsequent quantitative pilot study. Figure A presents the items used for the quantitative pilot study together with English translations.

Figure A.

English translations are for illustrative purposes only. DP = disease prevention; HC = health care; HLS-EU-Q = European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire; HP = health promotion.

In the second pretest phase, we found no significant differences in how participants responded to either the original or the alternative item format; therefore, we selected the original HLS-EU-Q item format to allow for maximum comparability.

Discussion

This is the first study to develop an age-adapted version of the HLS-EU-Q. A preliminary 26-item adaptation of the questionnaire was developed for German-speaking children age 9 and 10 years and tested qualitatively. The resulting questionnaire was geared toward the life experience of children at this particular age by taking into consideration both epidemiological data and knowledge gained from childhood studies. Researchers with a range of different professional backgrounds were involved in the development process. This made the process discursive, allowed a critical review of the drafting of an item pool, and permitted a final selection of well-performing items.

The questionnaire developed in this study provides a preliminary tool that draws on previous research and focuses on an age group that has yet to receive much attention in this field. It addresses children's perceived difficulty in accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying health-related information in the contexts of health care, disease prevention, and health promotion. It is also a measure of generic health literacy because it does not focus on just one health topic but addresses multiple topics such as “health-related communication,” “nutrition,” “health care,” and “medication adherence.”

This study was also able to highlight some critical aspects when using a version of the HLS-EU-Q adapted for children. Cognitive pretests demonstrated that items that theoretically address four different action areas (i.e., accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying health information) are not identified as such by a portion of the participants. In particular, items designed to assess participants' perceived difficulty in accessing and appraising health information were often answered on the basis of knowledge and habits. In these cases, the respective items did not assess participants' assessment of their capacity to engage successfully in such actions as accessing or appraising health information, but rather their assessment of how knowledgeable they were about the health topic at hand. This relates directly to issues of content and construct validity; when there is ambiguity regarding what is actually being measured (perceived difficulty or knowledge), validity is at stake. Future studies will need to investigate which cognitive processes participants use when responding to individual items and will also need to develop alternatives for specific items that are interpreted in different ways. Nonetheless, these considerations do not compromise the validity of the instrument as a whole because the cognitive pretest has shown that the majority of items are indeed interpreted as intended.

Lastly, it will also be important to investigate whether problems of misinterpretation can also be observed in qualitative tests of the original HLS-EU-Q on adults and adolescents. This will help clarify whether the findings reported here are specific to the target group of 4th-grade students or the particular selection of adapted items presented, or whether they point to more general problems when operationalizing the HLS-EU framework of health literacy. Although the HLS-EU-Q has been used in a notable number of studies (for an overview see Pelikan & Ganahl, 2017), cognitive testing does not seem to be a regular feature in this research. To the best of our knowledge, only three studies give detailed reports on the qualitative testing of the questionnaire (Domanska et al., 2018; Gerich & Moosbrugger, 2018; Storms, Claes, Aertgeerts, & Van den Broucke, 2017). These studies explored how HLS-EU-Q scores interrelate with health knowledge and attitudes (Gerich & Moosbrugger, 2018), and they identified problems due to a misunderstanding of terms (Domanska et al., 2018). They also found that participants with a low level of education had difficulties in indicating which answer applies to them due to abstraction problems and problems in distinguishing between the dimensions “appraising” and “applying” health information (Storms et al., 2017).

Study Limitations

The first limitation to the present findings is that the reported compilation of items represents one selected portion of a larger pool of items based on the HLS-EU-Q and the framework of health literacy. Although the item selection process was informed by the literature and by cognitive testing, other adaptations of items are possible for certain health topics or in the wording. Future research and further adaptations of the HLS-EU-Q will need to scrutinize the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Second, no members of the target group (i.e., children age 9 and 10 years) participated in drafting and selecting items. Target group participation might have improved the acceptability and relevance of the resulting questionnaire for the target group. However, this could not be carried out due to financial and time constraints.

Third, the psychometric properties of the questionnaire have yet to be investigated. Although the data presented here provide first hints on its dimensionality and reliability, a thorough examination of its validity and reliability is still necessary. This can be conducted only in a quantitative survey, which has also been carried out within the frame of this project. However, due to the limited scope of this article, psychometric properties and validation results are not reported here, but they will be reported in a forthcoming article (Bollweg et al., in press).

Fourth, the HLS-EU-Q, and thus the adaptation that we have developed are self-report questionnaires. As such, they do not provide an assessment of abilities but instead reflect respondents' subjective evaluation of perceived difficulty in dealing with health information. Such subjective evaluation might be based on several factors, including, but not limited to, self-efficacy, knowledge, empowerment, or trust in the health care system (Gerich & Moosbrugger, 2018). Also, such measurement might be prone to self-report bias. However, self-report measures have proven useful in addressing a more comprehensive definition of health literacy (Sørensen et al., 2012) that goes beyond the scope of the most common performance-based health literacy measures: health literacy does not only come into action when patients try to pronounce medical terms (cf. Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine; Davis et al., 1993) or extract information from a nutrition label (cf. Newest Vital Sign; Weiss et al., 2005), but it is used to deal with health information in a variety of situations in everyday life (Sørensen et al., 2012). Unless performance tests are capable of assessing different health literacy skills in everyday situations (e.g., finding, understanding, appraising, or applying health-related information), it has to be acknowledged that “[self-report] approaches to testing the definitions of health literacy in the general public may be an economically and ethically feasible approach that can be built upon” (Pleasant, 2014, p. 1498). Furthermore, self-report and performance-based measures are not necessarily mutually exclusive but instead may be different ways of looking at different aspects of health literacy. In this light, the combined assessment of both self-report and performance-based health literacy seems particularly fruitful.

Finally, it has to be stressed that the items presented here have been investigated only in the German language. The English translations by the authors are only illustrative and have not been subjected to the necessary professional back-translation process when applying English translations to studies of English-speaking children. Also, cultural adaptation and pretesting might be necessary when using the questionnaire in different languages and settings to determine whether all items are appropriate for the respective target groups.

Conclusions

This is the first study to deliver an age-adapted version of the HLS-EU-Q. A preliminary 26-item questionnaire was successfully developed that performed well in a qualitative pretest. However, further quantitative and qualitative studies of different samples are needed to verify the questionnaire's validity and reliability. The present findings provide information on advances in the measurement of generic self-reported HL in children and highlight the need for cognitive pretesting as an essential part of questionnaire development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Frank Faulbaum, PhD, Dawid Bekalarczyk, Dipl-Soz-Wiss, and Marc Danullis, Dipl-Soz, at the Social Sciences Survey Centre (SUZ, Duisburg, Germany) for consultation during the instrument development process and for coordinating the process of data collection and entry. They also thank Kristine Sørensen, PhD, Global Health Literacy Academy (Denmark); Luis Saboga Nunes, PhD, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa (Portugal); and Christiane Firnges, MPH, Frauenhauskoordinierung e.V. (The Association of Women's Shelters), Berlin (Germany), for providing feedback in the instrument development process. Lastly, they thank the following graduate assistants at the CPI, Bielefeld University: Katharina Kornblum, MA; Sandra Kirchhoff, MA; Sophie Langer, MA; Sandra Schlupp, MA; and Juri Kreuz, BA for their support in the recruitment process, verification of data entry, and drafting of information materials.

References

- Amoah P. A. Phillips D. R. Gyasi R. M. Koduah A. O. Edusei J. (2017). Health literacy and self-perceived health status among street youth in Kumasi, Ghana. Cogent Medicine, 4(1), 271 10.1080/2331205X.2016.1275091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollweg T. M. Okan O. (2019). Measuring children's health literacy: Current approaches and challenge. In Okan O., Bauer U., Levin-Zamir D., Pinheiro P., Sørensen K. (Eds.), International handbook of health literacy. Research, practice and policy across the lifespan (pp. 83–97). Policy Press, Bristol, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Bollweg T.M. Okan O. Fretian A. M. Bröder J. Domanska O. Jordan S. Bauer U. (in press). Adapting the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire for 4th-Grade students in Germany: Validation and psychometric analysis, HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borzekowski D. L. G. (2009). Considering children and health literacy: A theoretical approach. Pediatrics, 124(Suppl. 3), S282–S288 10.1542/peds.2009-1162D PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T. C. Long S. W. Jackson R. H. Mayeaux E. J. George R. B. Murphy P. W. Crouch M. A. (1993). Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: A shortened screening instrument. Family Medicine, 25(6), 391–395 PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domanska O. M. Firnges C. Bollweg T. M. Sørensen K. Holm-berg C. Jordan S. (2018). Do adolescents understand the items of the European health literacy survey questionnaire (HLS-EUQ47) - German version? Findings from cognitive interviews of the project “measurement of health literacy among adolescents” (MOHLAA) in Germany. Archives of Public Health, 76(1), 46 10.1186/s13690-018-0276-2 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drennan J. (2003). Cognitive interviewing: Verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42(1), 57–63 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02579.x PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong T. V. Aringazina A. Baisunova G. Nurjanah Pham T. V. Pham K. M. Chang P. W. (2017). Measuring health literacy in Asia: validation of the HLS-EU-Q47 survey tool in six Asian countries. Journal of Epidemiology, 27(2), 80–86 10.1016/j.je.2016.09.005 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerich J. Moosbrugger R. (2018). Subjective estimation of health literacy - What is measured by the HLS-EU scale and how is it linked to empowerment? Health Communication, 33(3), 254–263 10.1080/10410236.2016.1255846 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S. Armstrong R. Waters E. Sathish T. Alif S. M. Browne G. R. Yu X. (2018). Quality of health literacy instruments used in children and adolescents: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 8(6), e020080 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020080 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HBSC-Studienverbund Deutschland(2015). Health behaviour in school-aged children. Retrieved from http://hbsc-germany.de/downloads/faktenblatter-national/

- Kamtsiuris P. Atzpodien K. Ellert U. Schlack R. Schlaud M. (2007). Prävalenz von somatischen erkrankungen bei kindern und jugendlichen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des kinder-und jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS). [Prevalence of somatic diseases in German children and adolescents. Results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz, 50(5–6), 686–700 10.1007/s00103-007-0230-x PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K. Osaka W. Togari T. Ishikawa H. Yonekura Y. Sekido A. Matsumoto M. (2015). Comprehensive health literacy in Japan is lower than in Europe: A validated Japanese-language assessment of health literacy. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 505 10.1186/s12889-015-1835-x PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okan O. Bröder J. Pinheiro P. Bauer U. (2017). Gesundheitsförderung und health literacy. [Health promotion and health literacy]K. M. In Lange A., Steiner C., Schutter S., Reiter H. (Eds.), Handbuch kindheits-und jugendsoziologie (Vol. 124, pp. 1–21). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden; 10.1007/978-3-658-05676-6_48-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okan O. Lopes E. Bollweg T. M. Bröder J. Messer M. Bruland D. Pinheiro P. (2018). Generic health literacy measurement instruments for children and adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 166 10.1186/s12889-018-5054-0 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormshaw M. J. Paakkari L. Kannas L. (2013). Measuring child and adolescent health literacy: A systematic review of literature. Health Education, 113(5), 433–455 10.1108/HE-07-2012-0039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan J. M. Ganahl K. (2017). Measuring health literacy in general populations: Primary findings from the HLS-EU Consortium's health literacy assessment effort. In Logan R. A., Siegel E. R. (Eds.), Studies in health technology and informatics (Vol. 240). Health Literacy: New directions in research, theory and practice (pp. 34–59). IOS Press Incorporated; 10.3233/978-1-61499-790-0-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleasant A. (2014). Advancing health literacy measurement: A pathway to better health and health system performance. Journal of Health Communication, 19(12), 1481–1496 10.1080/10810730.2014.954083 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England (2015). Local action on health inequalities. Improving health literacy to reduce health inequalities: Practice resource. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-action-on-health-inequalities-improving-health-literacy

- Rees G. Main G. (2015). Children's views on their lives and well-being in 15 countries: an initial report on the Children's Worlds survey, 2013–14. Children's Worlds Project (International Survey of Children's Well-Being). [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C. O. Fahland R. A. Franze M. Splieth C. Thyrian J. R. Plachta-Danielzik S. Kohlmann T. (2010). Health-related behaviour, knowledge, attitudes, communication and social status in school children in Eastern Germany. Health Education Research, 25(4), 542–551 10.1093/her/cyq011 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen K. Pelikan J. M. Röthlin F. Ganahl K. Slonska Z. Doyle G. Brand H. the HLS-EU Consortium. (2015). Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU). European Journal of Public Health, 25(6), 1053–1058 10.1093/eurpub/ckv043 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen K. Van den Broucke S. Fullam J. Doyle G. Pelikan J. Slonska Z. Brand H. the (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. (2012). Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 80 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen K. Van den Broucke S. Pelikan J. M. Fullam J. Doyle G. Slonska Z. Brand H. the HLS-EU Consortium. (2013). Measuring health literacy in populations: Illuminating the design and development process of the European health literacy survey questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health, 13(1), 948 10.1186/1471-2458-13-948 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storms H. Claes N. Aertgeerts B. Van den Broucke S. (2017). Measuring health literacy among low literate people: An exploratory feasibility study with the HLS-EU questionnaire. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 475 10.1186/s12889-017-4391-8 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toçi E. Burazeri G. Sørensen K. Kamberi H. Brand H. (2015). Concurrent validation of two key health literacy instruments in a South Eastern European population. European Journal of Public Health, 25(3), 482–486 10.1093/eurpub/cku190 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl S. (2012). Alter und methode. Ein vergleich telefonischer und persönlicher leitfadeninterviews mit kindern [Age and method. A comparison of telephone and personal guideline interviews with children]. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-531-94308-4.

- Wallmann B. Gierschner S. Froböse I. (2012). Gesundheitskompetenz. Was wissen unsere schüler über gesundheit? [Health literacy. What do our students know about health?]. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung, 7(1), 5–10 10.1007/s11553-011-0322-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B. D. Mays M. Z. Martz W. Castro K. M. DeWalt D. A. Pignone M. P. Hale F. A. (2005). Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Annals of Family Medicine, 3(6), 514–522 10.1370/afm.405 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Shanghai declaration on promoting health in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Health Promotion International, 32(1), 7–8 10.1093/heapro/daw103 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]