Abstract

This study reports on the drug use outcomes in an efficacy trial of a culturally grounded, school-based, substance abuse prevention curriculum in rural Hawaiʻi. The curriculum (Hoʻouna Pono) was developed through a series of pre-prevention and pilot/feasibility studies funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and focuses on culturally relevant drug resistance skills training. The present study used a dynamic wait-listed control group design (Brown, Wyman, Guo, & Pena, 2006), in which cohorts of middle/intermediate public schools on Hawaiʻi Island were exposed to the curriculum at different time periods over a two-year time frame. Four-hundred and eighty six youth participated in the study. Approximately 90% of these youth were 11 or 12 years of age at the start of the trial. Growth curve modeling over six waves of data was conducted for alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes/e-cigarettes, crystal methamphetamine, and other hard drugs. The findings for alcohol use were contrary to the hypothesized effects of the intervention, but may have been a reflection of a lack equivalence among the cohorts in risk factors that were unaccounted for in the study. Despite this issue, the findings also indicated small, statistically significant changes in the intended direction for cigarette/e-cigarette and hard drug use. The present study compliments prior pilot research on the curriculum, and has implications for addressing Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander health disparities.

Keywords: culturally grounded prevention, efficacy, Native Hawaiian, youth, substance abuse

In numerous studies, Native Hawaiian youth have been found to report the highest rates of alcohol (Makini et al., 2001; Nigg, Anderson, Troumbley, Alam, & Keller, 2013; Nishimura, Hishinuma, & Goebert, 2013), tobacco (Glanz, Maskarinec, & Carlin, 2005; Glanz, Mau, Steffen, Maskarinec, & Arriola, 2007; Kim, Ziedonis, & Chen, 2007), and other drug use (Mayeda, Hishinuma, Nishimura, Garcia-Santiago, & Mark, 2006; Wong, Klingle, & Price, 2004) among predominant youth ethnic groups in Hawaiʻi. Substance use has been associated with adverse behavioral and health consequences for Hawaiian youth, such as suicidality (Else, Andrade, & Nahulu, 2007), school absences, suspensions, and infractions (Hishinuma et al., 2006), and aggressive behavior (Helm & Okamoto, 2016; Helm, Okamoto, Kaliades, & Giroux, 2014), emphasizing the pressing need to address substance use disparities for these youth. Despite this need, there continues to be a lack of substance abuse research focused on Native Hawaiian youth, including culturally tailored intervention research designed to prevent the use of substances over time (Durand, Cook, Konishi, & Nigg, 2015; Edwards, Giroux, & Okamoto, 2010).

To address this gap in the prevention and health disparities research, the purpose of this study is to describe the substance use outcomes in an efficacy trial of a school-based curriculum based on cultural values and beliefs of rural Hawaiian youth. Although the curriculum’s cultural focus may seem narrow or specific, prior research has indicated that it also has broader relevance to non-Hawaiian youth in rural communities (Okamoto, Kulis, Helm, Lauricella, & Valdez, 2016). Native Hawaiian culture is at the core of “local” culture in Hawaiʻi, which encompasses the social and behavioral norms of multiple Asian and Pacific Islander ethnic groups (Okamura, 1980). This is particularly the case for communities in rural Hawaiʻi, where higher proportions of Native Hawaiians are concentrated and exert a stronger cultural and social influence compared to urban areas in the State. As a result, the cultural focus of the curriculum directly addresses Native Hawaiian substance use disparities, while also having broader implications for rural health promotion across the State.

The curriculum (Hoʻouna Pono) was developed from a series of pre-prevention and pilot/feasibility prevention studies utilizing community-based participatory research principles and practices on Hawaiʻi Island (Helm & Okamoto, 2013). A prior pilot study of the curriculum evaluated variables considered distal to substance use (i.e., perceived risk in accepting drug offers, use of resistance strategies associated with lower drug use); however, due to methodological limitations, it was unable to evaluate the actual use of substances over time (Okamoto et al., 2016). The present study focuses on substance use outcomes across a two-year time frame associated with the implementation of the curriculum, in order to complement the findings from the earlier pilot study.

Literature Review

Substance Abuse Prevention for Indigenous Youth

A recent systematic literature review of substance abuse prevention curricula for Indigenous youth identified a total of 14 empirical studies published between 1988 and 2016 (Liddell & Burnette, 2017). Of the studies identified by Liddell and Burnette, only 5 (36%) examined substance use behavioral outcomes. In one of these studies, Schinke, Tepevac, and Cole (2000) found that American Indian youth participating in a culturally tailored life skills program had a slower growth rate of smokeless tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use over time, compared with youth in the control condition. All five of the studies identified by Liddell and Burnette focused on American Indian youth populations from different regions, such as the Northern Plains (Schinke et al., 2000) or the Pacific Northwest (Donovan et al., 2015). In terms of research design, only four of the studies in Liddell and Burnette’s review employed the use of a comparison group and/or a randomized controlled trial methodology in the evaluation of their curricula. Finally, only two of the studies in their review focused on Native Hawaiian youth (Helm et al., 2015; Okamoto et al., 2016). Helm et al. (2015) described the development of a substance abuse prevention curriculum for rural Hawaiian youth using community-based participatory action research principles and procedures. Okamoto et al. (2016) described the development and evaluation of the pilot version of Hoʻouna Pono in rural public schools on Hawaiʻi Island.

Earlier systematic research reviews have also corroborated the lack of prevention and/or intervention research focused on Native Hawaiian and/or Pacific Islander youth found by Liddell and Burnette (Durand et al., 2015; Edwards et al., 2010; Rehuher, Hiramatsu, & Helm, 2008). To the best of our knowledge and to date, there has been only one published substance abuse prevention trial focused on substance use outcomes of Hawaiian youth. Kim, Withy, Jackson, and Sekaguchi (2007) conducted an assessment of the Pono Curriculum, which was a culturally based prevention curriculum focused on risk and protective factors related to substance use for rural Hawaiian youth. While the findings of the curriculum were promising in the areas of alcohol and hard drug use, the reductions were found to be non-significant. Further, due to its grassroots nature, the trial lacked a control or comparison group to evaluate intervention effects. Nonetheless, the study was foundational for the future development and evaluation of culturally grounded curricula for Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander youth, such as the curriculum evaluated in the present study.

In sum, reviews of substance abuse prevention for Indigenous youth have identified significant gaps in the prevention research. Not only is there an overall lack of published empirical evaluations of substance abuse curricula for Indigenous youth, but the evaluations that have been published have rarely focused on substance use outcomes over time, employed rigorous research methodologies, or have focused on Native Hawaiian and/or Pacific Islander youth populations. The present study fills this research gap by addressing these three areas.

Purpose of the Study

The present study builds upon past pilot/feasibility research evaluating the Hoʻouna Pono curriculum. Okamoto et al. (2016) evaluated a pilot (7-lesson) version of the curriculum using randomized controlled trial procedures. Compared to the control group, the youth receiving the Hoʻouna Pono curriculum maintained or sustained their use of non-confrontational drug resistance strategies (avoid, explain, and leave) at 6-month follow up, and thought about consequences resulting from accepting drug offers significantly more than youth in the control group. While findings related to these distal factors were promising, the pilot study was underpowered to evaluate actual substance use behaviors. The pilot study utilized a modest sample size (N = 213), and an abbreviated version of the curriculum that limited the full exposure to the active ingredients of the curriculum (i.e., resistance skills). These limitations most likely affected the ability for the study to detect intervention effects related to substance use. The present study broadened the sampling frame from the pilot evaluation, and used a full-length version of the curriculum which included two additional videos and lessons, in an attempt to increase the overall power to detect intervention effects.

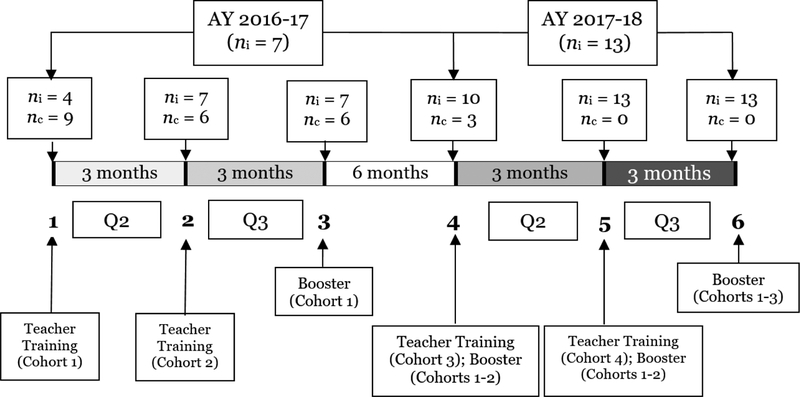

The hypothesis of the present study is that youths’ exposure to the Hoʻouna Pono curriculum will slow their use of alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes/e-cigarettes, crystal methamphetamine, and other hard drugs over time, compared to youth that have not been exposed to the curriculum. The study used a dynamic wait-listed control group design (Brown et al., 2006), in which schools were randomized into four cohorts and were exposed to the curriculum at different times over a two-year period (see Figure 1). As a result, substance use trajectories should be flatter for schools exposed to the curriculum earlier in the trial, compared to those exposed to the curriculum later in the trial. This trend would reflect the proposed preventive effect of the curriculum, as it would illustrate how the curriculum differentially slows the rate of youths’ substance use behaviors as a function of time. Youth exposed earlier to the curriculum (e.g., those in Cohort 1 schools) should show less substance use over time (i.e., flatter trajectories), compared to youth exposed later to the curriculum (e.g., those in Cohort 3 schools). Thus, Cohort 3 serves as a “proxy” control group in our study, since they have the shortest amount of time among the three cohorts to practice the culturally relevant drug resistance strategies introduced in the Hoʻouna Pono curriculum.

Figure 1.

Dynamic Wait-listed Control Group Design for Hoʻouna Pono

N= 13 Hawaiʻi Island Public Schools

ni = n (intervention group), nc = n (control group), Q2 = Academic Quarter 2,

Q3 = Academic Quarter 3, AY = Academic Year

Method

Participants and Procedures

All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Hawaiʻi Pacific University, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Education. Active parental consent and student assent were required for all participants in the study. Five hundred and fifty seven students from 13 different middle, intermediate, or multi-level schools on Hawaiʻi Island returned parental consent forms prior to survey administration. Fifty-eight students (10%) received parental consent to participate in the study, but were absent on the day of baseline survey administration in their respective schools. These students were deemed non-eligible for participation in the study. Ten students (2%) returned parental consent forms in which parents refused to allow their child to participate in the study. Three students (>1%) indicated that they did not wish to participate in the study. Subsequently, 486 youth participated in the efficacy trial. These students were permitted to complete surveys as part of the study; however, because the curriculum was approved through the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Education as an experimental educational practice, youth who were not participating in the study were also allowed to receive the curriculum. The demographic characteristics of the sample by cohort are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Variables by Cohort

| Variable | C1 (n = 95) |

C2 (n = 94) |

C3 (n = 185) |

C4 (n = 112) |

Total (N = 486) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female) | 51.6 (49) | 48.9 (46) | 54.6 (101) | 50.9 (57) | 52.1 (253) |

| Age | |||||

| 10 | 4.2 (4) | 0 | 5.4 (10) | 12.5 (14) | 5.8 (28) |

| 11 | 28.4 (27) | 40.4 (38) | 55.1 (102) | 68.8 (77) | 50.2 (244) |

| 12 | 62.1 (59) | 48.9 (46) | 36.2 (67) | 18.8 (21) | 39.7 (193) |

| 13 or older | 5.3 (5) | 10.6 (10) | 3.2 (6) | 0 | 4.3 (21) |

| Free/Reduced Lunch | 84.6 (77) | 72.0 (67) | 64.3 (117) | 60.0 (66) | 68.7 (327) |

| Ethnicity* | |||||

| Chinese | 30.9 (29) | 22.3 (21) | 27.3 (50) | 20.0 (22) | 25.4 (122) |

| Filipino | 60.6 (57) | 55.3 (52) | 40.4 (74) | 31.8 (35) | 45.3 (218) |

| Hawaiian/Pt. Hawaiian | 57.4 (54) | 56.4 (53) | 53.6 (98) | 50.9 (56) | 54.3 (261) |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 16.0 (15) | 6.4 (6) | 19.1 (35) | 14.5 (16) | 15.0 (72) |

| Japanese | 20.2 (19) | 31.9 (30) | 19.7 (36) | 29.1 (32) | 24.3 (117) |

| Korean | 5.3 (5) | 3.2 (3) | 7.1 (13) | 4.5 (5) | 5.4 (26) |

| Portuguese | 29.8 (28) | 34.0 (32) | 33.3 (61) | 20.0 (22) | 29.7 (143) |

| Samoan | 6.4 (6) | 5.3 (5) | 7.7 (14) | 10.0 (11) | 7.5 (36) |

| White | 29.8 (28) | 17.0 (16) | 36.6 (67) | 34.5 (38) | 31.0 (149) |

| Other Asian | 7.4 (7) | 5.3 (5) | 3.8 (7) | 4.5 (5) | 5.0 (24) |

| Other Pacific Islander | 12.8 (12) | 6.4 (6) | 13.7 (25) | 14.5 (16) | 12.3 (59) |

Note: Values reported in percentages and raw numbers (in parentheses)

Participants were allowed to select more than one ethnic group on the survey. Due to the high proportion of multi-ethnic youth in Hawaiʻi, percentages do not equal 100 percent.

C1 = Cohort 1, C2 = Cohort 2, C3 = Cohort 3, C4 = Cohort 4

Schools participating in the study were geographically focused within three school complex areas in the Department of Education on Hawaiʻi Island, and comprised 87% of all public middle or intermediate public or public/charter schools on the island. Unlike schools on O’ahu, many of the schools on Hawaiʻi Island are widely dispersed within small townships with populations of less than 50,000. Compared with middle/intermediate school youth on other islands, those on Hawaiʻi Island reported the highest rates of aggressive behavior (fighting, bullying), and tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use, as part of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (Saka, Takeuchi, Fagaragan, & Afaga, 2014).

Research Design

This study used a dynamic wait-listed control group design, which is a “roll out” design that has been applied in the evaluation of prevention interventions in educational settings (Henry, Tolan, Gorman-Smith, & Schoeny, 2017). The decision to employ a dynamic wait-listed control group design in this study was based on community feedback, and balanced scientific rigor with the community’s expectation for all schools participating in the efficacy trial to receive the intervention. The thirteen middle, intermediate, or multi-level schools participating in the study were block randomized into four cohorts by school size (see Figure 1). Small schools had enrollments less than 100 students, medium schools had enrollments between 101–500 students, and large schools had enrollments greater than 500 students. Each cohort received the Hoʻouna Pono curriculum at different time periods over the two-year efficacy trial. Cohorts 1 and 2 received the curriculum during the 2016–2017 academic year, while Cohorts 3 and 4 received the curriculum during the 2017–2018 academic year.

Within two weeks prior to implementing the first lesson of the curriculum, an eight-hour, face-to-face training was conducted by the curriculum developers for teachers implementing the curriculum (see Training and Implementation Fidelity section). Six waves of data were collected across two consecutive academic quarters (Quarters 2 and 3) during each academic year (see Figure 1). As a result, all schools were evaluated at pre-test and immediate post-test, and schools in Cohorts 1–3 received follow up evaluations. Schools in Cohort 1 received follow ups at 3-, 9-, 12-, and 15-months post-intervention, Cohort 2 at 6-, 9-, and 12-months post-intervention, and Cohort 3 at 3-months post-intervention. Prior to each follow-up evaluation, a brief (10–15 minute) booster session was conducted to remind students about the resistance skills covered in the curriculum. Students received the Hoʻouna Pono curriculum as part of their health, social studies, or physical education classes.

Surveys were administered by trained project staff and research assistants during health or physical education classes in participating schools. Public school teachers and/or counselors assisted in the coordination of the survey administration (e.g., compiling lists of eligible students prior to each wave of data collection), but were not present during survey administration. All parts of the survey were read aloud by project staff to students to aid in the comprehension of the survey items. This may have also had the secondary outcome of mitigating respondent fatigue, and also allowed the project staff to clarify and emphasize specific survey questions (e.g., smoking cigarettes included the use of e-cigarettes).

The Hoʻouna Pono Curriculum

Hoʻouna Pono is a classroom-based, video-enhanced curriculum aligned with the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Education Content and Performance Standards in Health (6–8 grade; Hawaiʻi State Department of Education, 2005). The curriculum’s focus on middle/intermediate school-aged youth stems from culturally grounded research which found that this age range is the ideal time to intervene for the prevention of substance use (Marsiglia, Kulis, Nieri, Yabiku, & Coleman, 2011). The full-length version of the curriculum evaluated in this study updated and extended a pilot version of the curriculum, and was validated by Hawaiʻi Island community stakeholders in a series of individual interviews prior to implementation (Okamoto, Helm, Ostrowski, & Flood, 2018). The curriculum consists of nine 45–60 minute lessons primarily focused on resistance skills training. Reviews of youth drug prevention programs have indicated resistance skills training to be a highly effective preventative approach, particularly when conducted within a social influence model of prevention (McBride, 2003; Skiba, Monroe, & Wodarski, 2004). Further, a study found that preadolescents who were highly competent in using drug resistance skills had a significantly lower probability of recent substance use compared to other sampled youth (Hopfer, Hecht, Lanza, Tan, & Xu, 2013).

Specifically, the curriculum is centered on brief video vignettes of Hawaiian youth engaged in realistic drug-related problem situations. These situations serve as the platform for facilitated learning (Harthun, Dustman, Reeves, Marsiglia, & Hecht, 2009), where youth are able to use life experiences stemming from the vignettes as part of the context for resistance skills training. Core drug resistance strategies covered in the curriculum include overt refusal of drug offers, explaining the reasons behind drug refusal, avoiding situations where drugs might be present, redirecting the topic away from drug use, and leaving a situation where drugs are present (Okamoto, Helm, & Dustman, 2015). Each video vignette depicts a situation where drugs and/or alcohol are being offered to Hawaiian youth and a matched set of three different resistance strategies. The situations and resistance strategies depicted in the videos were identified and validated in multiple pre-prevention studies in rural Hawaiʻi (Helm et al., 2008; Okamoto, Helm, Delp, et al., 2011; Okamoto, Helm, Giroux, Edwards, & Kulis, 2010; Okamoto, Helm, Giroux, & Kaliades, 2011; Okamoto, Helm, Giroux, Kaliades, et al., 2010; Okamoto, Helm, Kulis, Delp, & Dinson, 2012; Okamoto, Kulis, Helm, Edwards, & Giroux, 2010, 2014). Each video focuses on the unique familial and relational context of drug offers on Hawaiʻi Island, such as receiving an offer from cousins to take a beer from a cooler during a family party, or receiving an offer to drink beer from an intoxicated parent.

Eight of the nine lessons incorporate one 4–7 minute video vignette. All lessons in the curriculum followed the same basic format–an introduction and/or review of the past lesson, a culture wall activity, a video, 1–2 interactive activities, and a wrap-up activity (Okamoto et al., 2015). The culture wall activity involved the discussion and application of Hawaiʻi Island cultural concepts to drug prevention. For example, the concept of puʻuhonua (place of refuge) is used to introduce the concept of psychosocial “protection” in lesson 2 of the pilot curriculum. Other lessons encourage youth to consider the applicability of Hawaiian cultural constructs (e.g., ‘ohana, aloha) to drug prevention through the culture wall activity and facilitated discussions. The interactive activities following the videos introduce specific resistance skills and relate directly to the characters in the videos.

Training and Implementation Fidelity.

Teachers were trained to implement the curriculum through a free, credit-granting course sanctioned through the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Education. Given the wide geographic dispersion of schools in the study, training and implementation fidelity were conducted using a hybrid format, combining in-person and virtual support. Teachers participated in an 8-hour, in-person training, in which the curriculum was described, and several curricular activities were demonstrated by the program developers and role-played by the teachers. Teachers were also granted access to a Teacher Implementation Website, which included all of the lessons, worksheets, and videos, published research related to the curriculum, a discussion board, and a video conferencing link. The discussion board was facilitated by one of the program developers, and allowed teachers to post their comments and questions related to the curriculum, as well as photos of youth-generated work or students participating in the lessons. It allowed teachers to receive timely responses to their questions regarding the lessons, while also allowing the curriculum developers to monitor the implementation fidelity of the curriculum. The website was accessible via computers and smartphones to promote ease of use for the teachers.

Instrument

Items used to evaluate the curriculum were drawn largely from validated measures of another evidence-based, culturally grounded drug prevention curriculum (keepin’ it REAL; Hecht et al., 2003), and were used to evaluate the pilot version of Hoʻouna Pono (Okamoto et al., 2016). The instrument included demographic items, and items related to culture/enculturation (9 items), risk and protective factors (including drug use frequency, 14 items), drug resistance strategies (6 items), and risk assessment (14 items). Internal consistency on all subscales from the pilot study of the curriculum was moderate to high (i.e., Culture/Enculturation α =.79, Risk Assessment α = .83, and Resistance Strategies α = .92) except for Risk/Protective Factors (Risk α = .57, Protective α = .50).

Due to the focus on substance use behaviors as the dependent variables in the present study, analyses are focused on five specific items used to measure recent (past 30-day) use frequency of alcohol, cigarettes/e-cigarettes, marijuana, “ice” (crystal methamphetamine), and other hard drugs. Alcohol use was measured with “How often, in the last 4 weeks, have you drunk alcohol (beer or liquor)?” Cigarette/e-cigarette use was measured with “How often, in the last 4 weeks, have you smoked cigarettes, including e-cigarettes?” Marijuana use was measured with “How often, in the last 4 weeks, have you smoked marijuana?” “Ice” (crystal methamphetamine) use was measured with “How often, in the last 4 weeks, have you used ‘ice’?” Hard drugs was measured with “How often, in the last 4 weeks, have you used hard drugs other than “ice” (like crack, cocaine, speed, ecstasy, sniffing glue or paint)?” The 5-point Likert scale for each question was “never” (1), “only once” (2), “a few times” (3), “once a week” (4), and “almost every day” (5).

Data Analysis

We used growth curve modeling (GCM) to examine trajectories of substance use across the six waves of data collected over the two-year time frame. GCMs fit a line to the trajectories of outcomes as measured over time (Jackson, 2010). We explored unconditional models to evaluate two types of GCMs—a linear (straight line) and a quadratic (curved line) model. In cases where the quadratic estimates were non-significant, then only the linear model was reported in the conditional models that included predictors. We used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) adjustments in Mplus to provide estimates for any missing data for all cases with initial pre-test (Wave 1) data. We also used the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors estimator in Mplus (MLR) to address the skewed distributions in the dependent variables. The growth curve models accounted for nesting at the school level by including adjustments for school-level random effects. The intraclass correlations due to school-level clustering were small, varying from .02 to .05.

There were several issues that needed to be addressed prior to analysis. First, two of the three schools in Cohort 4 were unable to implement the curriculum to a majority of their students participating in the study. One of these schools refused to implement the curriculum immediately before their implementation date, while the other chose to implement the curriculum only to a small subset of their eligible student population. Thus, due to these school-level decisions that caused high levels of non-random attrition within the cohort, we decided to eliminate Cohort 4 from the longitudinal analyses in the study. Upon completion of this process, the overall sample for longitudinal analysis in this study was 374. Second, tests for baseline equivalence at initial pre-test found significant differences on a number of characteristics that may have influenced responsiveness to the curriculum (e.g., sports participation, ability to understand and speak the Hawaiian language). We adjusted for two of these characteristics—student age at the first survey and socioeconomic status, as measured by receipt of a free of reduced cost school lunch (see Table 1). Specifically, Cohorts 1 and 2 were significantly older than Cohort 3, χ2 (2, N = 374) = 30.9, p < .001, while the proportion of youth receiving free or reduced cost school lunch declined significantly from Cohort 1 to Cohort 3, χ2 (2, N = 366) = 12.2, p < .01. Eighty-five percent of youth in Cohort 1 received a free or reduced cost lunch, compared with sixty-four percent in Cohort 3. The cohorts did not differ significantly by gender or Native Hawaiian background.

The predictors in the model were dummy variables representing differences among the three cohorts, as well as the controls for lack of baseline equivalence (age, school lunch). Because of the expectation that the earlier intervention timing for Cohort 1 would produce relatively better (flatter) substance use growth trajectories for them (compared to Cohorts 2 and 3), we used Cohort 1 as the omitted reference group in these models. Dummy variable estimates for Cohorts 2 and 3 in each model indicated whether, and in what direction, the trajectories for Cohorts 2 and 3 differed from Cohort 1. To represent time as accurately as possible, and to make the models converge more readily, we inserted an extra time point in the middle of the timeline that corresponds to mid-summer between the two academic years. This addition had the effect of spreading out all the survey waves evenly.

Results

Overall, there were very low use rates for all substances. The percentage of students indicating the recent use of different substances at Wave 1 was as follows: Alcohol (5.6%), cigarettes/e-cigarettes (4.3%), marijuana (2.1%), hard drugs (1.7%), and crystal methamphetamine (1.2%). By Wave 6 the prevalence of recent use had doubled or more for some substances and declined slightly for others, but remained low overall: 10.7% for alcohol, 3.5% for cigarettes/e-cigarettes, 7.2% for marijuana, 0.6% for hard drugs, and 0.9% for crystal methamphetamine.

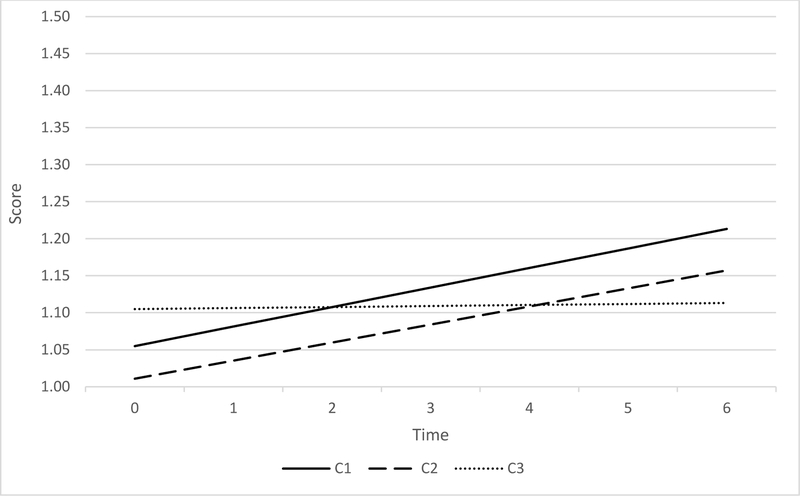

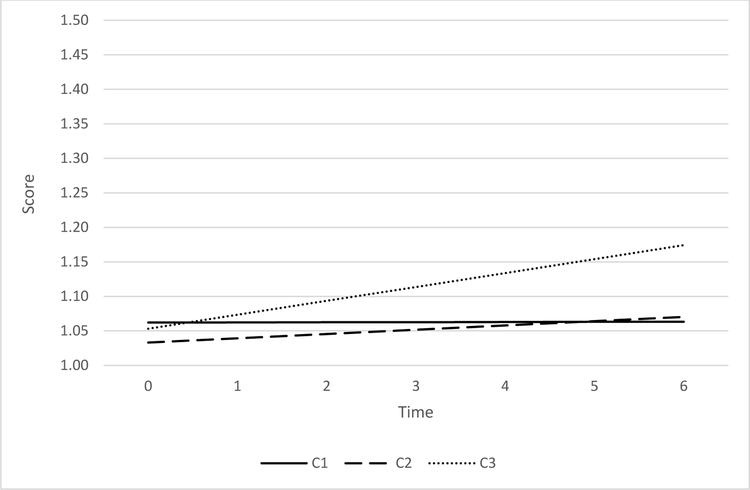

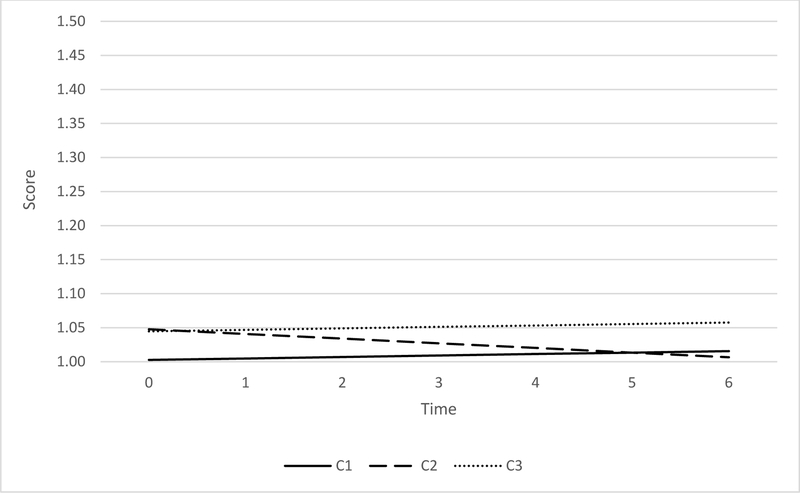

Table 2 shows the results of growth curve models for each of four substances. The top panel for initial use indicates where there were differences at Wave 1 in the frequency of use of each substance. While age and SES were included in these models to adjust for baseline differences among the cohorts, these demographics were not significant predictors of substance use at Wave 1. Further, except for hard drug use, there were no differences among the cohorts in initial levels of use. Compared to Cohort 1, both Cohort 2 and Cohort 3 reported higher frequency of hard drug use at baseline. The bottom panel of the table predicts the growth rate over the two-year time frame, confirming that it was small for all substances, which can be seen in the non-significant estimates for the intercepts. Because there were no significant quadratic (curvilinear) effects for modeling growth these are not presented in the table. Further, there were no estimates for use of “ice”, because the models would not converge, most likely due to extremely low use rates (~1%). There were, however, linear cohort differences for alcohol, cigarette/e-cigarette, and hard drug use, but not for marijuana use. For alcohol use, Cohort 3 had a significantly flatter linear growth trajectory than Cohort 1, while the trajectory for Cohort 2 did not differ from Cohort 1 (see Figure 2). For cigarette/e-cigarette use, Cohort 3 had a trajectory that grew significantly more steeply than Cohort 1, while the trajectory for Cohort 2 did not differ from Cohort 1 (see Figure 3). Finally, for hard drug use, although Cohorts 2 and 3 reported higher use than Cohort 1 at initial pre-test, Cohort 2 reported significantly decreasing growth compared to Cohort 1 over time (see Figure 4).

Table 2.

Linear Growth Curve Models for Recent Substance Use

| Alcohol | Cigarettes | Marijuana | Hard Drugs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | |

| Initial Use | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.574 | 0.294 | 0.782*** | 0.060 | 0.593 | 0.221*** | 0.943*** | 0.285 |

| Age (Years) | 0.042 | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.042 | 0.021 | 0.004 | 0.024 |

| SES (Lunch) | −0.005 | 0.021 | 0.037 | 0.024 | 0.043 | 0.036 | 0.019 | 0.022 |

| Cohort 2 | −0.044 | 0.041 | −0.029 | 0.031 | −0.097 | 0.076 | 0.045** | 0.016 |

| Cohort 3 | −0.050 | 0.009 | −0.009 | 0.022 | −0.064 | 0.071 | 0.042*** | 0.012 |

| Linear Growth | ||||||||

| Intercept | −0.035 | 0.112 | 0.014 | 0.073 | −0.065 | 0.094 | 0.049 | 0.070 |

| Age (Years) | 0.006 | 0.009 | −0.002 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.004 | 0.006 |

| SES (Lunch) | −0.011 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.010 | −0.006 | 0.015 | −0.001 | 0.003 |

| Cohort 2 | −0.002 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.005 | −0.003 | 0.024 | −0.009** | 0.003 |

| Cohort 3 | −0.025** | 0.009 | 0.020* | 0.009 | −0.011 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| N | 374 | 374 | 374 | 374 | ||||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 2.

Alcohol use trajectories for Cohorts 1–3

Note: Time 0 = Wave 1, Time 1 = Wave 2, Time 2 = Wave 3, Time 3 = Midpoint, Time 4 = Wave 4, Time 5 = Wave 5, Time 6 = Wave 6

C1 = Cohort 1, C2 = Cohort 2, C3 = Cohort 3

Figure 3.

Cigarette/e-cigarette use trajectories for Cohorts 1–3

Note: Time 0 = Wave 1, Time 1 = Wave 2, Time 2 = Wave 3, Time 3 = Midpoint, Time 4 = Wave 4, Time 5 = Wave 5, Time 6 = Wave 6

C1 = Cohort 1, C2 = Cohort 2, C3 = Cohort 3

Figure 4.

Hard drug use trajectories for Cohorts 1–3

Note: Time 0 = Wave 1, Time 1 = Wave 2, Time 2 = Wave 3, Time 3 = Midpoint, Time 4 = Wave 4, Time 5 = Wave 5, Time 6 = Wave 6

C1 = Cohort 1, C2 = Cohort 2, C3 = Cohort 3

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine substance use behavioral changes over time as part of a culturally grounded drug prevention efficacy trial in rural Hawaiʻi. The findings varied by type of substances, and provided partial support for the efficacy of the curriculum. For alcohol use, there was a non-significant difference between Cohorts 1 and 2, which could have been due to the short gap (three months) between the implementation of the curriculum. For both of these cohorts, there were small increases in alcohol use over time, which were not observed in Cohort 3. Overall increases in alcohol use over time were found in evaluations of other culturally focused, evidence-based substance use prevention curricula (Hecht et al., 2003; Schinke et al., 2000). For example, Hecht et al. (2003) found that alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use increased in both the intervention and control conditions within their 16-month randomized controlled trial of ‘keepin it R.E.A.L.; however, the increase was significantly less for intervention students compared to control students. Growth patterns for alcohol use for Cohorts 1 and 2 in the present study were similar to those of the intervention groups in the Schinke et al. and Hecht et al. studies; however, in the present study, they were steeper than the comparison group’s (i.e., Cohort 3’s) virtually flat trajectory. It is possible that the intervention may not have had a preventive effect on alcohol use. However, based on our team’s in-depth, accumulated knowledge of Hawaiʻi Island schools and communities, we feel that the unanticipated between-group differences could be accounted for by the lack of equivalence in risk factors among groups in the present study. Although we adjusted for lack of baseline equivalence in age and socioeconomic status at pre-test and block randomized assignment of schools into cohorts, Cohort 3 schools may have been less impacted by risk factor variables unaccounted for in the study, but associated with age and/or socioeconomic status (e.g., negative peer influences, family risk factors), compared to Cohort 1 and 2 schools. More broadly, the elevated free or reduced cost school lunch rates for Cohorts 1 and 2 may also have been indicative of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, which can contribute to chronic stress and concomitant youth substance use (Mennis, Stahler, & Mason, 2016). The disproportionate influence of these risk factor variables by cohort may have contributed to the flatter alcohol use trajectories over time for Cohort 3, compared to Cohort 1 and 2 schools. Although the findings may indicate a non-preventive effect of the intervention for alcohol use, we feel that it is more likely they are a reflection of a lack of equivalence among the cohorts in risk factors that were unaccounted for in the study.

Nonetheless, despite cohort differences which may have biased lower substance use risk for Cohort 3, we found small, significant differences in the expected direction for cigarette/e-cigarette use, as well as promising findings for preventing hard drug use. The difference between groups for hard drug use was particularly small, pointing to the need to balance practical versus statistical significance in the interpretation of this finding. However, these positive findings suggest that the curriculum might exert its strongest impact on curbing the use of emerging or novel substances, such as electronic nicotine delivery systems, versus long-standing and heavily used substances, such as alcohol. Twenty-seven percent of all middle school youth in the state of Hawaiʻi have tried an electronic nicotine delivery system, ranking first nationally among all states collecting data on middle school youth (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). Further, Hawaiʻi Island ranks the highest in lifetime and current cigarette and e-cigarette use for middle school youth, compared with other islands across the state of Hawaiʻi (Hawaiʻi State Department of Health, 2018). Notably, thirty-two percent of middle school aged youth on Hawaiʻi Island reported trying an electronic nicotine delivery system, with 19% indicating regular use. Compared to middle school aged youth on other islands, youth on Hawaiʻi Island also have reported the highest lifetime use rates for cocaine, ecstasy, and inhalant use (Hawaiʻi State Department of Health, 2018). The findings from the present study are promising, in terms of addressing the disproportionately high cigarette, e-cigarette, and hard drug use rates for middle school youth on Hawaiʻi Island.

Limitations of the Study

There were several limitations in this study. The primary limitation was the potential lack of equivalence between cohorts along key characteristics that were influential to the drug use outcomes over time. Although we adjusted for lack of baseline equivalence across cohorts in age and socioeconomic status, other associated, influential variables, such as negative peer influences or family risk factors, may have exerted a disproportionate influence between cohorts on substance use over time in this study. Our survey instrument did not measure these types of influences; therefore, they were unable to be factored into our analysis. In order to address the issue of influential variables unaccounted for in our study, block randomization based on geographic region and/or socioeconomic status may have been warranted. This process may have distributed the level of school and community risk factors more equitably across cohorts.

Another limitation of the study is potential selection effects, due to the requirement of active parental consent for youths’ participation in the study. While only 2% of the students in our study returned parental consent forms indicating their childs’ non-participation in the study, there were a number of students in participating schools who never returned the consent form. These students were not allowed to participate in the study. Despite written assurances of confidentiality in the parental consent form (including a description of a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health that was secured prior to the study), recent research in rural Hawaiʻi has described how youth in higher-risk environments may be underrepresented in school-based drug and alcohol studies, due to parental concerns that their personal drug-using behaviors might be exposed (Okamoto et al., 2014). The potential underrepresentation of higher-risk youth may have impacted the generalizability of the research findings in this study.

There were two other notable limitations to our study. Pre-adolescent developmental changes in the sample may have affected the findings, such that intervention effects could have been offset by the natural tendency of children to use substances as they get older. Finally, there was a limitation in measurement, as we did not separate regular cigarette use from e-cigarette use in our survey. Based on recent prevalence data (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018), we deduced that the trajectories were most likely accounted for by e-cigarette use in our study. However, future research should separate regular cigarette use from e-cigarette use, in order to more accurately determine the impact of the curriculum by substances.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the present study provides modest support for the efficacy of the Hoʻouna Pono curriculum. The findings related to cigarette/e-cigarette use have implications for cancer control and prevention for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and address the emerging epidemic of youths’ use of electronic nicotine delivery systems in Hawaiʻi schools and communities. Further, the findings related to hard drug use suggest that the curriculum may help interrupt youths’ transition from “gateway” substance use to more severe substance use. Despite these promising findings, more research is needed to examine the impact of the curriculum on youth alcohol and marijuana use, as well as longitudinal research that examines the impact of the curriculum beyond the two-year time frame of the present study. Future research may also incorporate moderation tests of the curriculum to determine whether differences in substance use trajectories vary by ethnicity or other demographic characteristics. Future directions for this study will include the implementation, adoption, and sustainability of the curriculum within the Hawaiʻi State Department of Education and within rural Hawaiian communities.

Public Significance Statement.

This study examined the effectiveness of a substance abuse prevention curriculum based on rural Native Hawaiian culture in Hawaiʻi. It contributes to the fields of culturally grounded prevention and rural health, and advances our knowledge of psychosocial interventions for Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander youth.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA037836–01A1), with supplemental funding from the College of Health and Society Scholarly Endeavors Program, Hawaiʻi Pacific University. Data analysis for this study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA038657) and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01 MD006110). All authors declare no other conflicts of interest in the publication of this study. The authors acknowledge Wilda Cielo and Nikolas Herrera for their assistance with data collection and management. A version of this article was presented at the 27th Annual Society for Prevention Research Conference in San Francisco, CA.

Contributor Information

Scott K. Okamoto, Hawaiʻi Pacific University

Stephen S. Kulis, Arizona State University

Susana Helm, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Steven Keone Chin, Hawaiʻi Pacific University.

Janice Hata, Hawaiʻi Pacific University.

Emily Hata, Hawaiʻi Pacific University.

Awapuhi Lee, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

References

- Brown CH, Wyman PA, Guo J, & Pena J (2006). Dynamic wait-listed designs for randomized trials: New designs for prevention of youth suicide. Clinical Trials, 3, 259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). 1995–2017 Middle School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Retrieved from http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/

- Donovan DM, Thomas LR, Sigo RLW, Price L, Lonczak H, Lawrence N, … Bagley L (2015). Healing of the Canoe: Preliminary results of a culturally grounded intervention to prevent substance abuse and promote tribal identity for native youth in two Pacific Northwest tribes. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 22(1), 42–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand Z, Cook A, Konishi M, & Nigg C (2015). Alcohol and substance use prevention programs for youth in Hawaii and Pacific Islands: A literature review. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 15(3), 240–251. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2015.1024811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C, Giroux D, & Okamoto SK (2010). A review of the literature on Native Hawaiian youth and drug use: Implications for research and practice. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 9(3), 153–172. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2010.500580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else IRN, Andrade NN, & Nahulu LB (2007). Suicide and suicidal-related behaviors among indigenous Pacific Islanders in the United States. Death Studies, 31(5), 479–501. doi: 10.1080/07481180701244595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Maskarinec G, & Carlin L (2005). Ethnicity, sense of coherence, and tobacco use among adolescents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 29(3), 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Mau M, Steffen A, Maskarinec G, & Arriola KJ (2007). Tobacco use among Native Hawaiian middle school students: Its prevalence, correlates and implications. Ethnicity & Health, 12(3), 227–244. doi: 10.1080/13557850701234948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harthun ML, Dustman PA, Reeves LJ, Marsiglia FF, & Hecht ML (2009). Using community-based participatory research to adapt keepin’ it REAL: Creating a socially, developmentally, and academically appropriate prevention curriculum for 5th graders. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 53(3), 12–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawaiʻi State Department of Education. (2005). Hawaiʻi Content & Performance Standards III Database (Health, Grades 6–8). Retrieved from http://165.248.72.55/hcpsv3/search_results.jsp?contentarea=Health&gradecourse=6-8&strand=&showbenchmark=benchmark&showspa=spa&showrubric=rubric&Go%21=Submit

- Hawaiʻi State Department of Health. (2018). Indicator-Based Information System for Public Health. Retrieved from http://ibis.hhdw.org/ibisph-view/

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kulis S, Dustman P, & Miller-Day M (2003). Culturally grounded substance use prevention: An evaluation of the keepin’ it R.E.A.L. curriculum. Prevention Science, 4(4), 233–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, Lee W, Hanakahi V, Gleason K, McCarthy K, & Haumana. (2015). Using photovoice with youth to develop a drug prevention program in a rural Hawaiian community. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 22(1), 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, & Okamoto SK (2013). Developing the Hoʻouna Pono substance use prevention curriculum: Collaborating with Hawaiian youth and communities. Hawaiʻi Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 72(2), 66–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, & Okamoto SK (2016). Gendered perceptions of drugs, aggression, and violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0886260516660301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, Okamoto SK, Kaliades A, & Giroux D (2014). Drug offers as a context for violence perpetration and victimization. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 13(1), 39–57. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.853015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, Okamoto SK, Medeiros H, Chin CIH, Kawano KN, Po’a-Kekuawela K, … Sele FP (2008). Participatory drug prevention research in rural Hawaiʻi with Native Hawaiian middle school students. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 2(4), 307–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, Tolan P, Gorman-Smith D, & Schoeny M (2017). Alternatives to randomized control trial designs for community-based prevention evaluation. Prevention Science, 18(6), 671–680. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0706-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hishinuma ES, Else IRN, Chang JY, Goebert DA, Nishimura ST, Choi–Misailidis S, & Andrade NN (2006). Substance use as a robust correlate of school outcome measures for ethnically diverse adolescents of Asian/Pacific Islander ancestry. School Psychology Quarterly, 21(3), 286–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer S, Hecht ML, Lanza ST, Tan X, & Xu S (2013). Preadolescent drug use resistance skill profiles, substance use, and substance use prevention. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 34(6), 395–404. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0325-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DL (2010). Reporting results of latent growth modeling and multilevel modeling analyses: Some recommendations for rehabilitation psychology. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(3), 272–285. doi: 10.1037/a0020462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R, Withy K, Jackson D, & Sekaguchi L (2007). Initial assessment of a culturally tailored substance abuse prevention program and applicability of the risk and protective model for adolescents of Hawaiʻi. Hawaiʻi Medical Journal, 66, 118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SS, Ziedonis D, & Chen K (2007). Tobacco use and dependence in Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents: A review of the literature. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 6(3), 113–142. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n03_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell J, & Burnette CE (2017). Culturally-informed interventions fo r substance abuse among Indigenous youth in the United States: A review. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 14(5), 329–359. doi: 10.1080/23761407.2017.1335631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makini GK Jr., Hishinuma ES, Kim SP, Carlton BS, Miyamoto RH, Nahulu LB, … Else IRN (2001). Risk and protective factors related to Native Hawaiian adolescent alcohol use. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 36(3), 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Yabiku ST, Nieri TA, & Coleman E (2011). When to intervene: Elementary school, middle school, or both? Effects of keepin’ It REAL on substance use trajectories of Mexican heritage youth. Prevention Science, 12(1), 48–62. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0189-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda DT, Hishinuma ES, Nishimura ST, Garcia-Santiago O, & Mark GY (2006). Asian/Pacific Islander youth violence prevention center: Interpersonal violence and deviant behaviors among youth in Hawaiʻi. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(2), 276.e271–276.e211. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride N (2003). A systematic review of school drug education. Health Education Research, 18(6), 729–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, Stahler GJ, & Mason MJ (2016). Risky substance use environments and addiction: A new frontier for environmental justice research. Interantional Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13, 1–15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13060607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg CR, Anderson JK, Troumbley R, Alam MM, & Keller S (2013). Recent Trends in Adolescent Alcohol Use in Hawaiʻi: 2005–2011. Hawaiʻi Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 72(3), 92–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura ST, Hishinuma ES, & Goebert D (2013). Underage drinking among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 12(3), 259–277. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.805176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Delp JA, Stone K, Dinson A, & Stetkiewicz J (2011). A community stakeholder analysis of drug resistance strategies of rural Native Hawaiian youth. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 32(3–4), 185–193. doi: 10.1007/s10935-011-0247-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, & Dustman PJ (2015). Hoʻouna Pono Drug Prevention Curriculum: Teacher training manual (2nd ed.). Honolulu, HI: Hawaiʻi Pacific University. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Giroux D, Edwards C, & Kulis S (2010). The development and initial validation of the Hawaiian Youth Drug Offers Survey (HYDOS). Ethnicity & Health, 15(1), 73–92. doi: 10.1080/13557850903418828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Giroux D, & Kaliades A (2011). “I no like get caught using drugs”: Explanations for refusal as a drug-resistance strategy for rural Native Hawaiian youths. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 20(2), 150–166. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2011.570131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Giroux D, Kaliades A, Kawano KN, & Kulis S (2010). A typology and analysis of drug resistance strategies of rural Native Hawaiian youth. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(5–6), 311–319. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0222-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Kulis S, Delp JA, & Dinson A (2012). Drug resistance strategies of rural Hawaiian youth as a function of drug offerers and substances: A community stakeholder analysis. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23(3), 1239–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Ostrowski LK, & Flood L (2018). The validation of a school-based, culturally grounded drug prevention curriculum for rural Hawaiian youth. Health Promotion Practice, 19(3), 369–376. doi: 10.1177/1524839917704210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Edwards C, & Giroux D (2010). Gender differences in drug offers of rural Hawaiian Youths: A mixed-methods analysis. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 25(3), 291–306. doi: 10.1177/0886109910375210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Edwards C, & Giroux D (2014). The social contexts of drug offers and their relationship to drug use of rural Hawaiian youths. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 23(4), 242–252. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2013.786937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Lauricella M, & Valdez JK (2016). An evaluation of the Hoʻouna Pono curriculum: A pilot study of culturally grounded substance abuse prevention for rural Hawaiian youth. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 27(2), 815–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura JY (1980). Aloha Kanaka Me Ke Aloha ‘Aina: Local culture and society in Hawaii. Amerasia, 7(2), 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Rehuher D, Hiramatsu T, & Helm S (2008). Evidence-based youth drug prevention: A critique with implications for practice-based contextually relevant prevention in Hawaiʻi. Hawaiʻi Journal of Public Health, 1(1), 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Saka SM, Takeuchi L, Fagaragan A, & Afaga L (2014). Results of the 2013 Hawaiʻi state and counties Youth Risk Behavior Surveys (YRBS) and cross-year comparisons. Honolulu, HI: Curriculum Research & Development Group, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Tepavac L, & Cole KC (2000). Preventing substance use among Native American youth: Three-year results. Addictive Behaviors, 25(3), 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skiba D, Monroe J, & Wodarski JS (2004). Adolescent substance use: Reviewing the effectiveness of prevention strategies. Social Work, 49(3), 343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Klingle RS, & Price RK (2004). Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among Asian American and Pacific Islander Adolescents in California and Hawaii. Addictive Behaviors, 29(1), 127–141. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(03)00079-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]