Abstract

The dismantlement of evidence-based environmental governance by the Trump Administration requires new forms of activism that uphold science and environmental regulatory agencies while critiquing the politics of knowledge production. The Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI) emerged after the November 2016 U.S. Presidential elections, becoming an organization of over 175 volunteer researchers, technologists, archivists, and activists innovating more just forms of government accountability and environmental regulation. Our successes include: 1) leading a public movement to archive vulnerable federal data evidencing climate change and environmental injustice; 2) conducting multi-sited interviews of current and former federal agency personnel regarding the transition into the Trump administration; 3) tracking changes to federal websites. In this article, we conduct a “social movement organizational autoethnography” on the field of movements intersecting within EDGI and on our theory, tactics, and practices. We offer ideas for expanding and iterating on methods of public, collaborative scholarship and advocacy.

The Trump administration has sought to dismantle scientific norms and evidence-based environmental governance. This political situation requires new forms of collective action that can advocate for and uphold state science practices and environmental regulatory agencies while still maintaining a critical approach to their politics of knowledge production. In this article, we provide a “social movement organizational (SMO) autoethnography” of the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI), a North American network that includes 175 members from more than thirty different academic institutions and ten non-profit or grassroots organizations, as well as caring and committed volunteers who come from a broad spectrum of work and life backgrounds.

EDGI formed in the weeks after the November 2016 U.S. elections, and has concentrated on four main projects: 1) Web archiving: Between December 2016 and June 2017, EDGI helped coordinate forty-nine “DataRescue” events and build open-source tools for grassroots web-archiving to ensure continued public access to critical scientific research (see Walker et al. in press); 2) Interviewing federal employees: EDGI members have conducted 90 confidential interviews with current and former employees at the EPA and OSHA to document internal attacks on these agencies by Trump political appointees (such as the former EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt), preserve institutional memories, and contribute to ongoing media coverage of the current administration; 3) Website monitoring: EDGI tracks changes to tens of thousands of federal agency web pages, which analysts review a prioritized subset of on a weekly basis in order to compile reports and publish findings of socially-meaningful web page changes in collaboration with journalists (including EcoWatch, the New York Times, POLITICO, the Hill, the Washington Post, Vox, PBS Frontline, and CNN);[1] 4) Research and publications: EDGI also publishes its own research and analysis in public reports (Dillon, Sellers, and EDGI 2017; Paris, Lave, and UCS Science Network 2017; Whitington 2017) and scholarly journals (Dillon et al. 2017, 2018; Fredrickson et al. 2018; Walker et al. in press, Dillon et al. in press) and newspaper op-eds (EDGI 2018a).

Since December 2016, EDGI has successfully combined diverse research projects, academic disciplines, activist tactics, and social movement fields to form a concerted challenge to the Trump administration’s anti-science, anti-environmental agenda. In this article, we undertake a “social movement organization (SMO) autoethnography” that examines EDGI’s formation and situates the organization within a broader “field of movements” (Brown et al. 2010). We show how EDGI brought together activists, professionals, and scholars from data, environmental, and scientific communities, and argue that its successes were only possible because of the diverse skill sets, disciplines, and knowledge practices of its members. We also explore EDGI as a case study of “digitally-enabled social change” (Earl and Kimport 2011) by examining EDGI’s creation and use of web-based technologies and tools to bring together geographically dispersed social actors to work collaboratively, develop innovative social movement tactics, and quickly disseminate information to a broad audience. We describe EDGI’s unique structure--as a grassroots, horizontal organization, inspired by feminist values--that seeks to value different knowledge practices and forms of labor. Above all, members of EDGI, hailing from different disciplines and professional backgrounds, are united by the goal of “data resistance,” in which we develop new data infrastructures and technological strategies as tools of opposition to the Trump administration and to a longer legacy of inadequate and unevenly enforced environmental data and governance practices in the United States. In organizing, EDGI benefited from a rapidly changing and catalytic political opportunity structure in which diverse social movements were trying to figure out how to engage in resistance to a new administration while addressing long-standing issues such as a lack of government accountability.

Given our central goal to preserve data and institutional memory of federal environmental agencies while envisioning new forms of data stewardship and environmental governance, we recognize the importance of documenting our history and reflecting on it through a sociological lens. EDGI members’ different disciplinary approaches have unique contexts and desires for documentation: social scientists value ethnographic insights into how social movement organizations develop and operate; archivists and librarians value the preservation of the historical record and its attendant data; environmental historians value the historical record of individual and organizational responses to political events shaping the environmental landscape; and science and technology studies scholars value doing and explaining technologies of resistance, such as DataRescue events (which we describe below). The first part of the article provides methodological and theoretical context for EDGI’s organizing practices, focusing on the field of movements that shape our work and unique form of online collective activism. The second part of the article discusses the formation of EDGI to provide context about the background and orientations of our individual and institutional members. This part also discusses specific accomplishments and the types of data resistance that we engage in (e.g., data archiving, web monitoring, interviewing, and developing accessible and accountable infrastructures for data practices). A third section reflects on the aspects of EDGI organizing tactics and structure that makes these successes possible as well as some limitations to organizing thus far. We conclude with a section on EDGI’s self-presentation as an organization committed to positive visioning through the practice of data resistance.

SOCIAL MOVEMENT AUTOETHNOGRAPHY AND EDGI’S FIELD OF MOVEMENTS

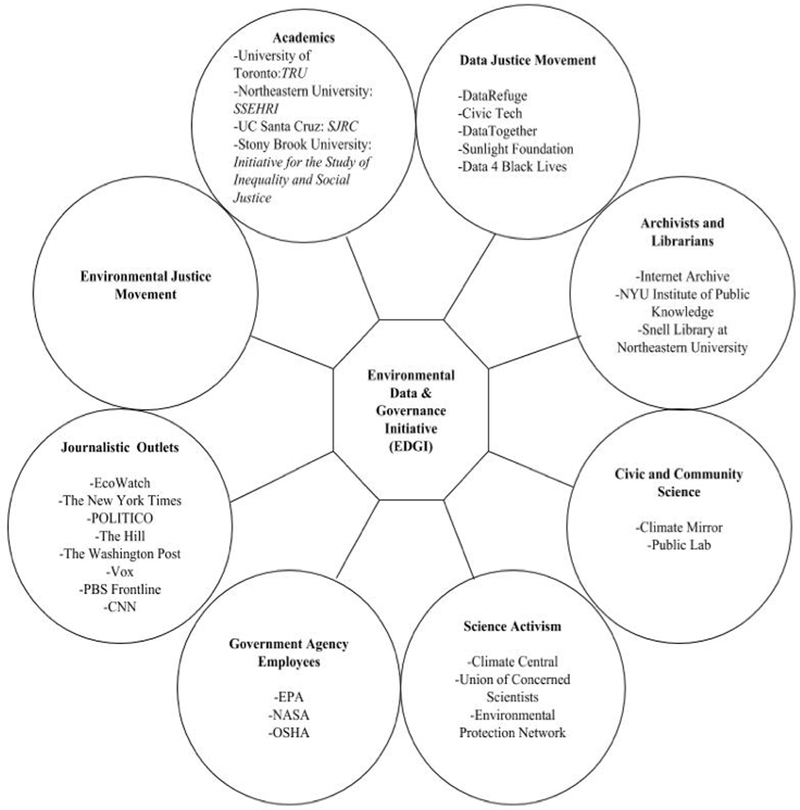

EDGI is a unique organization, operating in a field of movements that do not normally interact with each other but are increasingly finding common ground. Insights from various social movement and academic disciplines influence our work and tactics. We describe these guiding perspectives in Figure 1 as a “field of movements,” based on Phil Brown et al.’s (2010) “field analysis” approach that situates social movements within fields, which are multiple, broader social movement communities, discourses, and legacies (Martin 2003). These fields include strategic allies and coalition partners who may have conflicting perspectives or ideologies. Field analysis is informed by Raka Ray’s (1999) “fields of action,” Maren Klawiter’s (1999) “cultures of action,” Adele Clarke and Susan Star’s (2008) “social worlds,” and is integral to the practice of SMO autoethnography. Below, we describe this practice and then map EDGI’s field of movements.

Figure 1:

EDGI Field of Movements

Social Movement Organizational Autoethnography

The concept of “SMO autoethnography,” a key lens through which we frame our analysis of EDGI, goes beyond traditional organizational autoethnography. As originally formulated, organizational autoethnography is a method to “illuminate the relationship between the individual and the organization” (Boyle and Parry 2007, 185). Continued work under this approach consistently focuses on the individual’s place in the organization (Herrmann 2017). SMO autoethnography is different in that it is the collectively-produced, self-reflexive representation of an organization itself and the social and historical context in which members organize. In its most successful form, SMO autoethnography is not simply an individual member’s description of the organization, but a collectively-produced analysis that situates the organization within its broader “field of movements” (Brown et al. 2010).

EDGI’s Contributions to Online Collective Action

Since its formation in November 2016, EDGI has developed unique forms of online collective action in two respects. First, as a geographically dispersed organization spanning multiple time zones, EDGI’s collaborative work and horizontal organizational structure are enabled by the use of online applications, including Google Drive, Zoom, Slack, GitHub, and HackMD. These spaces are not separate and interact with one another- Google Documents, Sheets, and Zoom meeting links are often dropped into Slack channels, and links to Slack conversations or channels may appear on the other platforms. These online technologies allow EDGI members to organize and collaborate on diverse projects without co-presence in time and space, and according to EDGI’s values of transparency and accessibility. Secondly, EDGI’s political goals have focused on online environmental data, alterations to government environmental agency websites, and developing an engaged framework of “environmental data justice.” Because of this, many of EDGI’s social movement tactics have not only required web-based tools but also the development of our own software and infrastructures for data archiving and website monitoring, which we detail below. In both respects (of web tool use and design) EDGI presents an important case study on the role of digital technologies in social movements.

Jennifer Earl et al. (2010) develop a typology of Internet activism to describe and differentiate uses and consequences of the Internet in political contention: (1) Brochure-ware: for example, when information is simply distributed through the Web; (2) Online facilitation of offline activism (such as when offline protest events use the Web for recruitment and/or logistical support); (3) Online participation: for example, online petitions or letter-writing campaigns; and (4) Online organizing: when entire campaigns and social movements are organized online, which Jennifer Earl and Katrina Kimport (2011) refer to as “e-movements.” One of the motivations for developing this typology is to display qualitative differences in forms of Internet activism and argue against reductive sociological analyses which have either dismissed Internet activism as ineffective or concluded that the Internet has fundamentally changed the nature of collective action. To this point, Earl et al. argue that although some forms of Internet activism, such as the use of websites and listservs (or “brochure-ware”), might increase the size, speed, and scale of collective action, they do not challenge existing social movement theories such as issue framing and resource mobilization (Benford and Snow 2000; McCarthy and Zald 1977). However, Earl et al. also argue that other forms of Internet activism, especially “e-movements,” have altered collective action in ways that require theoretical attention. E-movements, for example, are more akin to a flash flood and not necessarily led by formal social movement organizations (SMOs), nor do they require ongoing support or participation. Studies of e-movement “flash activism” or “five-minute activism” leads Earl et al. to suggest that social movement scholars should develop new theoretical models, moving beyond SMOs as the primary unit of analysis (also see Schussman and Earl 2004) and challenging existing sociological assumptions about the necessity of producing and maintaining collective identity.

EDGI’s working group activities and organizational structure include aspects of Earl et al.’s first three categories: brochure-ware (EDGI distributes online reports and maintains a Twitter account); online facilitation of offline activism (EDGI co-coordinated the 2016 DataRescue project, which we discuss below); and online participation (such as EDGI’s Web Monitoring working group and its collaborative online writing projects, like the “Hundred Days and Counting” Reports). EDGI is not an “e-movement,” as defined by Earl and Kimport (2011), although most of its member interactions and collaborations occur in online spaces, such as Slack, Zoom, or Google Documents. In blurring the boundaries of this typology, EDGI’s ecology of communication platforms offers a new case study of Internet activism for sociologists, one which exemplifies what Emiliano Treré and Alice Mattoni (2016) call the “communicative complexity of contemporary social movements.” EDGI’s success also reinforces Earl and Kimport’s (2011) assertion that the Web offers two specific “affordances,” a term used to describe particular actions enabled by technological design. Namely, Internet communication technologies can (though do not always) (1) reduce the costs of organizing and participation, and (2) reduce the requirement of co-presence for collective action to take place. EDGI provides a model of an organization that substantially leveraged both affordances of Internet communications technologies for collective action.

Indeed, EDGI’s organizational model is only possible through recently developed, Web-based platforms that allow EDGI members to collaborate and co-work without co-presence. By developing protocols for these communication platforms, EDGI seeks to limit the emergence of informal hierarchies and promote feminist practices of care. For example, if more than one member wants to speak in a Zoom meeting, they raise their hands and join the “stack” in the online chat bar, then wait their turn to speak (determined by the EDGI moderator), so all voices are heard. On Slack, most channels are open to all EDGI members, except for personally sensitive discussions or results from web monitoring before they are analyzed. Our collaborative writing protocol uses Google Documents to track edits and ensure changes to a document (such as this article) are approved by consensus. In the past, this process would have been time-consuming and inefficient, involving drafts being passed back and forth between multiple co-authors. Now, we have virtual co-writing sessions and chat with each other while we write an article, protocol, or report.

While literature on Internet activism focuses overwhelmingly on how and whether the Internet shapes social movements, we also ask how collective action shapes technological infrastructures. After reflecting on EDGI’s engagement with information technologies, we propose that a fifth type of group - “Infrastructural Internet activism” - should be added to Earl et al.’s (2010) typology for groups that create or re-configure online tools according to their own political goals. Data resistance falls into this category, for instance when EDGI designs online tools that reflect our mission, vision, and values of transparency and open infrastructures for federal environmental data. This involves the development of a collection of applications built on open-source, decentralized file system to archive data (Walker et al. in press), creation of an open-source software called “Scanner” to monitor websites, and an open database for environmental impact statements that are otherwise difficult to access. While many hacktivist and data justice groups would clearly be included in this category, non-tech specific groups are increasingly finding the need to re-configure and create their own technological infrastructures.[2]

It is also important to note differences between EDGI and other e-activist groups. Most significantly, as we discuss below, EDGI has its origins in several existing research organizations, two of which are physically based in universities and have faculty, students, and staff. Further, EDGI members have been physically present in group settings on many occasions, including DataRescue events, tag-on meetings of professional associations, work-group gatherings, and EDGI’s own retreat.

Political Opportunity Structure

Political opportunity structure (POS) theory argues that social movement outcomes are largely shaped by factors external to the movement organization itself, especially the political context, and that features of the POS influence the choice of activist strategies and the impacts of movements (Kitschelt 1986; McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald 1996). The POS is not fixed; rather it is dynamic and can be altered by activists and social movements (Meyer and Staggenborg 1996). EDGI’s data resistance--particularly the broad scale of the DataRescue project and the national media attention garnered by EDGI--must be understood in the context of massive, anti-Trump protests across many social sectors in the wake of the 2016 election results. These started with the influential Women’s March during the 2017 inauguration week and included marches and other activism defending science in general (such as the March for Science, held on Earth Day 2017), environmental agencies and policies, and also those defending immigrants (the airport protests in 2017), attacking racism and sexual predation (the #MeToo movement), and countering threats from ultra-right and fascist groups. Most specifically, EDGI was spurred by and continues to challenge the deep anti-environmentalism of the Trump administration. This includes climate change denial, withdrawal from the Paris Accord, elevation of oil industry leadership to top positions (e.g. Exxon’s CEO Rex Tillerson to his short tenure as Secretary of State), approval of the Dakota Access Pipeline, dismissal of academic researchers on EPA’s Science Advisory Board, the appointment of Scott Pruitt as EPA Administrator (who, as Oklahoma attorney General, had repeatedly sued the agency to try to weaken its environmental protections), and many other anti-environmental actions. In addition to large-scale science activism, support from sympathetic city and state governments on issues such as climate change has been an important resource for the POS that nourishes EDGI.

Contributing to the POS was a core of veteran scientists and other professionals in EPA and other federal agencies with environmental components (e.g. NIOSH, NOAA, DOE). These professionals were deeply threatened by the political appointees to the agencies, who disrupted their work. Some of those were members of existing EPA veterans’ groups, which provided further support. Having a trusted organization that could present their views to the public was enormously helpful to EDGI’s ability to gain access to many people for interviews and other material.

Opposition to Trump administration attacks on science was a strong element of the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), an organization of scientists and engineers dedicated to science-based solutions for issues around health, safety, and sustainability (Union of Concerned Scientists n.d.), as well as other science communication and advocacy organizations including Climate Central, a non-profit focused on communicating the effects of our changing climate to the public, and 314 Action, a non-profit political action committee supporting scientists running as candidates for public office. The stature and strength of these groups, combined with their interests in collaborating with EDGI (after EDGI’s DataRescue events had gained significant media attention), served as an additional opportunity for building an engaged network with groups that EDGI members had not worked with before. Independent scientists working on climate change, disasters, chemical regulation, and environmental health added to that opportunity as EDGI voiced their shared concerns through avenues such as blog posts and reports that were publicized by several media outlets (EDGI 2018b).

EDGI also benefited from how established institutions, from environmental non-profits to the media, were not well-equipped or prepared to reckon with the Trump administration’s far-reaching assault on federal environmental agencies and policy. The large environmental groups, despite ample staff and resources, had become accustomed during the eight years of the Obama administration and prior to organizing around particular environmental “issues” and influencing administrative proceedings that were similarly siloed. But from its transition teams onward, the Trump administration set about to undermine how entire agencies like the EPA worked, as well as discredit and dismantle established arenas of policy like those dealing with climate change. Moreover, neither the national groups nor print and online media had yet adjusted to just how much of environmental agencies’ work, from science to public outreach, now happened digitally via databases and websites. Established environmental groups had much expertise in particular policy arenas, but far less on the technologies and interfaces that governed so much of environmental agencies’ ties to the public. National media outlets, still undertaking their own far-reaching and often fraught migrations from print to web outlets, had devoted far less scrutiny to similar efforts by government agencies, and were far from ready for how the Trump administration might seek to manipulate these. Thus EDGI, with the participation of technically savvy programmers, archivists, and digital media experts, was able to fill a needed niche of protecting federal online data.

While POS typically examines the opportunities within state structures, EDGI’s utilization of political opportunity is about science politics, and as we have shown above, the opportunity structure has largely involved scientific communities, as well as science organizations. We employ Alissa Cordner et al.’s (2018) notion of “science opportunity structure” (SOS) to explain this derivative of POS. Cordner et al. formulated SOS to theorize how activists dealing with chemical contamination marshalled the resources of scientific researchers and institutions to press their claims of exposure and seek remediation and regulation. As they put it, SOS “explains how formal and informal organizational structures create opportunities and challenges for non-scientists to make claims on scientific knowledge and practices.” EDGI’s development has followed such a path, integrating the resources of diverse scientific communities: library science, data informatics, environmental science, environmental health, analytic chemistry, toxicology, and exposure science. Assembling a multidisciplinary approach to data politics, EDGI’s science opportunity structure drew from the opportunities offered by those many communities.

GENESIS OF A UNIQUE ORGANIZATION WITH MANY ROLES AND COMPONENTS

Here we describe our formation as a rapid response to Trump’s election and the pledge by his campaign and transition teams to dismantle or undermine the EPA’s important functions and roll back industry regulations, particularly within the petrochemical and fossil fuels sectors. From the beginning, EDGI self-organized into multiple working groups coordinated by a steering committee with representatives from each group, which draw on different strengths and disciplinary trainings. We situate our formation in the fields that held together the founders and subsequent members: environmental justice, data justice, science activism, and civic science. We address functions of our workgroups, our products, and the media coverage of our work in order to demonstrate the success of an organization that draws from several research fields and social movements and is built upon horizontal and participatory networks.

Founding the Organization

The fear of data and other information erasure from government websites, combined with deep concern about the overall threat to EPA and other agencies, led a group of academics to form EDGI in the weeks after the November 2016 elections. EDGI began as an e-mail conversation among a dozen colleagues from humanities and social science disciplines as well as environmental organizations. The people in this email exchange of original group were connected both directly through the distributed organization Public Lab, and through intellectual networks of STS scholars. For an example of the latter, some people at the Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute had past and present connections with people at the Technoscience Research Unit, both of which are well-established research units at major universities. EDGI has since grown into an interdisciplinary, cross-professional organization of over 175 members, and countless more volunteers, across the United States and Canada. During the presidential election, Donald Trump promised to get rid of the EPA “in almost every form” and called climate change a “hoax.” Myron Ebell, Trump’s appointee to lead the EPA transition team and the director of a Washington, D.C. think tank with a central role in promoting climate change denial, sought to carry this out. EDGI members were particularly concerned about government data removal given the legacy of the George W. Bush administration (2001–2009) and the Canadian government under Stephen Harper (2006–2015). These administrations demonstrated how erasing environmental data is central to deregulation and undermining environmental policy and agencies, as well as casting doubt and uncertainty on environmental issues such as climate change (Sellers et al. 2017).

In what was an unusually rapid organizational formation, by December 2016, approximately a month after Trump’s election and that initial e-mail, EDGI was up and running in its tasks to archive and preserve federal environmental datasets, monitor and report on changes to federal environmental agency websites, and interview past and present agency employees. While some founding members had collaborated on previous projects, in part through the established institutions discussed in detail below, this was the first time the majority were working together. Further, within the first two months individuals who had not been on that email joined EDGI through word of mouth and based on press coverage, eventually taking up coordinating roles. Organizationally, EDGI sought to build a structure that would mirror the transparency and democracy it sought in the world of government. We have a decentralized, consensus-based structure that relies on various online platforms, and organization-wide decisions are made by a steering committee in weekly meetings that are open to all EDGI members.

As Table 1 shows, EDGI had the benefit of its founding members being part of established institutes, both inside and outside of universities. The Technoscience Research Institute (TRU) at the University of Toronto had experience in drawing together social justice and science and technology studies approaches, as well as connections with the Toronto civic technology community, and lent its expertise in launching the data archiving work. At Northeastern University, the Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute (SSEHRI) had experience in environmental policy and toxics activism, and lent expertise in ethnographic and interviewing work. Public Lab, a community for Do-it-Yourself environmental science tools and methodologies could provide expertise in open-source technologies with an emphasis on online collaborative interactions. TRU, SSEHRI, and Public Lab all had strong environmental justice engagement and Science and Technology Studies roots, which helped give quick shape to the overall EDGI approach. They were also beginning to take up aspects of the new “data justice” movement that combined critique of exploitative and oppressive uses of data with a community-based approach to using data for the public good. TRU and SSEHRI had available postdocs and graduate students whom the faculty directors could interest in participating, making both centers very visible locations with EDGI’s network. Both institutes were also able to contribute funds from their institutional budgets, and SSEHRI’s full-time grants administrator was available to take on the extensive financial aspects. In sync with the civic science projects of SSEHRI and TRU, Public Lab had long experience as a civic science organization with a distributed structure involving a small number of paid staff and many volunteer members, and three founding EDGI members had strong connections to Public Lab. These provided EDGI with models for what a distributed organization could look like. Additionally, Public Lab was willing and able to provide fiscal sponsorship, enabling EDGI to quickly obtain foundation support without having to form as a 501-c-3 nonprofit. Below we address how EDGI was influenced by, and took up the mantle of, the arenas of environmental justice, data justice, science activism, and civic science.

Table 1.

Organizations Involved in Founding EDGI

| Organization | Location | General Activities | Resources for EDGI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technoscience Research Institute (TRU) | University of Toronto | Feminist STS; Indigenous STS; decolonial protocols; environmental data justice; supporting interdisciplinary social justice and STS research | First data rescue; faculty and grad students provided much infrastructure; provided funds |

| Public Laboratory for Open Technology and Science (Public Lab) | Distributed locations | Low-cost community environmental monitoring; civic science; open-source platform for continuous development | Early data rescue; serves as fiscal sponsor; model for a distributed SMO |

| Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute (SSEHRI) | Northeastern University | Academic-community partnerships and engaged scholarship; training interdisciplinary students and postdocs | Faculty, grad students, postdocs and grants administrator provided much infrastructure. |

Environmental Justice:

The three lead organizations, as well as many EDGI co-founders, are involved in environmental justice (EJ) research and/or activism, including working with EJ groups (such as Communities for a Better Environment; Center for Race, Poverty and the Environment; Alternatives for Community and Environment; West Harlem Environmental Action; Chelsea Greenroots; and Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice) to conduct both traditional and low-cost, innovative monitoring in regular and disaster settings (e.g. fracking sites, post-Katrina formaldehyde exposures in FEMA trailers, BP oil spill mapping), among other projects. The co-founders had long been engaged in meshing their academic positions with activism, and were not slowed down by concerns over whether activism was appropriate for academics.

The EJ movement gained traction in the early 1980s, with a focus on the disproportionate prevalence of hazardous pollution among communities of color and low-income communities and the role this played in the complex patterns of unequal health status. Civil rights organizations prompted much of the EJ movement, highlighting issues of race and class stratification in the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies, and pointing to injustices that the broader environmental movement had previously neglected (Mohai, Pellow, and Roberts 2009; Bullard 2008; Pellow 2000). EJ’s focus has greatly expanded beyond unequal exposures to pollution to include equitable access to transportation, healthy food, greenspaces, reproductive justice, climate justice, inclusive and ecological urban planning and regional development, workplace health and safety, health inequalities, impacts of disasters such as Hurricane Katrina, and the international trade of toxic waste (Agyeman et al. 2016). EJ growth as a major force in US society includes government action such as the establishment of EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice and funding from federal agencies including the EPA. EDGI immediately understood that Pruitt’s EPA would retreat on EJ, a concern that was shared by Mustafa Ali, the head of EPA’s EJ unit, who resigned soon after Pruitt’s appointment.

EDGI recognized the importance of government datasets for helping EJ organizations and academics formulate claims about racism and other injustices. Given this, the continued preservation and public accessibility of federal environmental data, including the Toxics Release Inventory, the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS), and a variety of climate change data, was identified by EDGI members as critical for helping demonstrate the disparate impacts of environmental contamination and climate change on low-income communities and communities of color. The EJ framework drives EDGI’s work conceptually in our commitment to combat racism in general and, more specifically, to reshape environmental data and policy to reduce environmental hazards that overburden low-income populations and communities of color. For example, we have extensively tracked environmental injustices occurring under the current administration, which are documented in several EDGI publications including Pursuing a Toxic Agenda: Environmental Injustice in the Early Trump Administration, the second installment of our “100 Days and Counting” report series, and a peer-reviewed article in the journal Environmental Justice (Dillon et al. 2017).

Data Justice:

EDGI founders were involved with, or at least interested in, the new but rapidly growing “data justice” movement. “Data justice” as a concept has been taken up to address the intersection between “big data” and social justice. As a result, much of the data justice world is concerned with “data harms,” namely how datafication adversely impacts or exploits individuals and groups (Dencik, Hintz, and Cable 2016; Taylor 2017; Heeks and Renken 2016). Examples include discriminatory action, such as using credit scores and neighborhood racial characteristics to deny loans, mortgages, or the ability to purchase homes through the practice of redlining. The field of data justice also concerns itself with issues such as the deliberate sales of personal privacy information, e-data breaches and the common cover-ups of their occurrences and outcomes, and political surveillance to control opposition political movements, carry out voter suppression, and enforce immigration status (Redden and Brand 2017).

Data justice activism counters those above examples and also takes on a wide range of attempts to seek restorative justice. Organizations like Detroit Digital Justice Coalition, Design Justice Network, and Our Data Bodies address issues such as surveillance through data collection and open data by weaving together critical perspectives on data, community skill-building projects, and collecting better data. EDGI membership includes people who have experience adopting data justice approaches and as a result, projects not only respond to potential data harms (e.g., through our archiving of vulnerable government data), but also aim to achieve restorative justice by creating new technical and social infrastructures. As such, EDGI initiated a project, Data Together, in partnership with two companies--qri.io and Protocol Labs--that goes beyond our initial focus on solely rescuing government data to developing open-source and user-friendly software that supports grassroots archiving efforts and community stewardship of data. This environmental data justice work recognizes that governmental environmental data, particularly industry self-reported data like the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory, can work to obscure rather than elucidate environmental justice questions. As a result, equity-focused environmental justice approaches to data need more public-facing and open-source tools to critically analyze the quality, creation and dissemination of data.

Science Activism:

Many EDGI members are experienced with the long tradition of science activism that, propagated by watchdog organizations such as the Health Policy Advisory Committee, Science for the People, and UCS, challenges anti-democratic uses of science, corporate conflicts of interest, industry attacks on scientists and advocates, and abuses of power by regulatory agencies (Moore 2008; Chowkwanyun 2011). There has been a general trend in this direction, as scientists have become more vocal in protesting assaults on science, including the February 19, 2017 stand-up-for-science rally that coincided with the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Boston, and the April 22, 2017 March for Science at 600 locations across the United States and internationally. Much as EDGI protects data, other scientists and their organizations have seen themselves as protecting science overall, including funding, openness, and practical applications (MacKendrick 2017).

Science activism research is also aided by the “New Political Sociology of Science” (NPSS) approach, whose scholars highlight the political-economic forces that shape the conceptualization, funding, production, and dissemination of science. NPSS emphasizes structural systems of power, while highlighting how knowledge production benefits more powerful groups, whether they are defined by race, class, gender, or professional status (Moore and Frickel 2006, Frickel and Hess 2014). This framework underlies much of the work of EDGI as we seek to analyze and highlight the immense power of data production, control, and application in upholding or undermining environmental protections. For example, our interviews with former and current EPA staff illustrate the extent to which pro-business leanings have captured the agency’s work as compared to previous administrations and the consequences this has for environmental and public health (Dillon et al. 2018).

Civic Science:

In EDGI’s archiving efforts that involve preserving federal website data, we are part of the civic science (aka “citizen science” and “community science”) movement. Extensive research on citizen science and community-based participatory research demonstrates the contributions made to scientific knowledge by laypeople. Crowdsourced data has been used in many studies such as wild bird counts, oil spill effects, and water pollution from fracking (Irwin 1995; Dickinson and Bonney 2012; Cavalier and Kennedy 2016; Wylie et al. 2014). In addition to gathering and integrating more scientific observations than possible in a more traditionally funded and operated project, crowdsourced data has the capacity to democratize the research process. While citizen science projects may involve a hierarchical structure of professionals directing amateur observers, the transition to “civic science” engages in popular governance with participants who shape the formation, production, and use of data.

The above four aspects of our work frame and practice are all examples of working at the academic-activist interface. The founders and many members were well-versed in such dual roles and were aware that these sometimes posed contrasting identities that required various types of navigation. Writing this article is indeed an exercise in dealing with these contrasts. A number of us are experienced in bridging activism with academic pursuits and have shared our experiences with those who are newer to this type of scholarship. Our resource-rich academic environments have supported this work, particularly our research centers, such as TRU, SSEHRI, and the Science and Justice Center, which were indeed formed around such a combination.

EDGI’s Organizational Structure

Despite its geographical dispersion across all North American time zones, EDGI is able to accomplish the kind of organizational transparency and reflexivity that enables autoethnography through multiple modes of virtual and in-person communication and working group activities. EDGI’s steering committee holds weekly online meetings, which are open to its members, recorded, and archived with meeting minutes. Each working group holds regular online meetings, which are archived on our shared Google Drive and YouTube channel. EDGI also holds occasional in-person meetings, the first of which was held concurrently with the Society for the Social Studies of Science (4S) conference that many members attended in August 2017, and we are currently planning a second annual dedicated group meeting. EDGI also uses the online work organization platform, Slack, which makes most of our various working group activities and conversation transparent and open to EDGI members (even if they are not involved in those projects). Each working group, whose outcomes are discussed in a later section, has its own regular meetings and develops reports to the whole organization that include how the working group mission dovetails with EDGI’s overall mission, deals with potential conflicts if working groups are not transparent enough in their processes, and educates others in the workflows and products of the working group. Weekly meetings often take up issues such as: how to better engage less-involved members, how to recruit and involve more individuals from traditionally marginalized backgrounds (especially in paid and leadership positions), and how to present EDGI to other organizations or the media. Some of these meetings go further, addressing the overall nature and direction of the organization, especially in light of a significant growth in foundation funding.

Extensive discussions produced several internal collectively-written documents that reflect our feminist practices of care (Tuck 2009; de la Bellacasa 2011) with regards to authorship practices, conflict of interest, and hiring practices. These documents are dynamic and open to changes as projects move forward or as we learn from situations that accompany our growth as an organization. These protocols are located in a shared Google Drive and detail topics such as who to speak to if there is a problem, communication in and outside of EDGI, how to post onto the website or blog, cyber security practices, and how to invite new members, among others. The web monitoring and archiving code and coordination efforts are also thoroughly documented and publicly visible on EDGI’s GitHub repository. These informative documents facilitate the co-production of knowledge and our horizontal structure since they de-mystify our practices, provide clear points of entry for new members, and any member can edit them. We consider this kind of feminist care work as a vital component to EDGI’s organizational successes and hope to serve as a model or starting point for other organizations seeking to engage in similar practices.

Another form of reflexivity is observed in all-EDGI discussions about what articles, reports, and op-eds to write. Even if articles are specialized products of workgroups, the whole organization is able to evaluate whether these are good uses of time and whether they will help develop the organization. Additionally, the steering committee reads final drafts (including this one) to ensure that they accurately reflect EDGI’s perspective. We take care to ensure that students, postdocs, and junior faculty get ample opportunity to be co-authors. Finally, the Environmental Data Justice working group, which will be elaborated on further, provides additional space for members to “slow down” and reflect on key questions such as how EDGI’s processes might counter or perpetuate systems of oppression and whether our practices align with our own mission, vision, and values (Dillon et al. 2018; Vera et al. under review). These forms of reflexivity and care are valuable because social movement organizations are usually caught up in the immediacy of their actions and have little time to explore their history and structure. Additionally, self-reflection helps social movement organizations illuminate their mission, tactics, strategy, and collaborations with other social movement and non-movement partners, and gauge their successes and shortcomings.

EDGI’s Projects

Here, we describe EDGI’s projects in order to illustrate how diverse movements and research fields have been operationalized into a broad, far-reaching strategy to document and respond to threats from the current administration, build participatory and responsive civic technologies and data infrastructures, and create new communities of practice to enable government and industry accountability.

Data Rescue:

EDGI collaborated with the Data Refuge initiative at the University of Pennsylvania and Civic Tech in Toronto and Chicago to create DataRescue, an effort to archive websites and datasets from federal environmental agencies. Participants at the first crowd-sourced archiving event in December 2016 at the University of Toronto archived EPA web pages and developed an open-source toolkit including event planning materials as well as web scraping scripts that were improved at future events. By June 2017, over forty-nine DataRescue events had taken place in cities across the United States and Canada. The DataRescue toolkit and eventual workflow was continually refined through this partnership so that each event contributed to overall archiving efforts. DataRescue archived web pages from the EPA, OSHA, NOAA, NASA, and other agencies by nominating URLs to the Internet Archive’s End-of-Term project and “harvesting” more complex datasets for public access through repositories like Data Refuge. Hundreds of people participated in DataRescue events, reflecting the public value of environmental agencies and science in the U.S., and providing an opportunity to resist the Trump administration’s attacks on science and environmental policy. Extensive media coverage of these rescue events, including by Newsweek and PC Magazine, contributed greatly to EDGI’s public presence and helped recruit new volunteers (see also Lamdan 2017 for a critical appraisal of DataRescue). Further, our relationship with Wayback Machine grew over the course of these events into a collaboration for our current phase of Web Monitoring efforts discussed below.

Web Monitoring:

A group of EDGI steering committee members soon realized that data resistance should go beyond archiving efforts to also tracking ongoing alterations of federal agency websites (Atkin 2017). We adapted methods and tools such as a fee-based software program called Versionista to crawl a selection of 25,000 web pages, mostly on the EPA, NASA, NOAA, the Department of Energy, and the Department of the Interior websites. The Web Monitoring Team consists of a group of volunteer web developers and web analysts that monitor, document, and disseminate changes to these websites. By spring of 2017, our Web Monitoring Team had become arguably the single-most authoritative source for reliable information on changes in federal environmental websites. The Social Science Research Council, aware of our work, invited an essay for the “Just Environments” section of their website (Dillon, Sellers, and EDGI 2017), and on November 14, 2017, seven Democratic senators led with EDGI’s website monitoring results when writing to EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt to request restoration of key climate science material on the EPA website from EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt. We also became an important source for the well-respected UCS, who have highlighted EDGI work in their public outreach. Now, in addition to continuing this monitoring and report writing, we are developing our own web monitoring software called Scanner that will be free, open-source, and publicly accessible.

The Web Monitoring project seeks to identify socially meaningful changes to federal websites then circulate reports on these changes to journalists and watchdog organizations. These reports inform the public of the scale and scope of the Trump administration’s effects on federal environmental agencies and offer a new model of government oversight and accountability. In addition to shorter, frequent reports, we publish longer analyses as well, including an October 17, 2017 report, Assessment of Removals and Changes in Access to Resources on the EPA’s ‘Climate and Energy Resources for State, Local, and Tribal Government’ Website (Bergman et al.). Additionally, one of EDGI’s “100 Days and Counting” reports entitled Changing the Digital Climate: How Climate Change Web Content is Being Censored Under the Trump Administration, which is part of a series that we will describe further, highlights the work of web monitoring and generated much press coverage (Rinberg et al. 2018).

Interviewing Project and Support for Agency Staff:

Beginning a month after the election, EDGI began its interviewing project in order to foster public knowledge and document changes at the EPA and OSHA, including presidential transitions and accompanying internal pressures faced by agency staff. Long-accumulated institutional memory and knowledge, as well as practices of evidence-based regulation were also at stake. EDGI was well prepared to investigate and document these internal workings with extended, open-ended interviews. Neither journalists nor NGOs were likely to pursue this time intensive project. EDGI also began to provide connections with the Environmental Protection Network, the EPA Alumni Association, and other formal and informal groups of present and past EPA staff, who are operating at varying levels of resistance to uphold EPA’s legacy of protecting public health and the environment. Providing support for that voice is certainly critical in light of EPA’s use of private investigators to probe the critical perspectives of EPA staff since the Trump administration took office (Lipton and Friedman 2017). In these ways, EDGI supports staff in manifesting their own forms of resistance to the Pruitt leadership. Concern and support for agency staff was more broadly voiced by activists at the “Stand up for Science” rally that a group of EDGI members had also attended on February 19, 2017 in Boston.

Ninety interviews with current and former employees have helped illuminate the Trump administration’s effects on the budgets, staffing levels, and overall capabilities of the agencies tasked with protecting environmental and human health. EDGI analyzed these transcripts and contextualized them with current news reporting and archival material in three “100 Days and Counting” reports. The first report, EPA under Siege: Trump’s Assault in History and Testimony documents how the Trump administration poses the greatest threat to the EPA in its forty-seven year history, comparable to efforts under Reagan to destroy it. The second report, Pursuing a Toxic Agenda: Environmental Injustice in the Early Trump Administration, demonstrates how the Trump administration has increased environmental risks for vulnerable communities through, for example, its support for the Dakota Access Pipeline, the reversal of a pending ban on the pesticide chlorpyrifos, and changes in workplace safety regulations. This report outlines how the Trump administration has proposed to dismantle or significantly reduce funding for environmental protections such as lead remediation and toxic cleanup, and limit access to publicly available environmental data through IRIS, which provides toxicological assessment of environmental contaminants. The third report, Changing the Digital Climate: How Climate Change Web Content is Being Censored under the Trump Administration provides extensive detail on the web monitoring results as we discussed earlier. These three reports have led to news stories in Mother Jones, Bill Moyers.com, the Washington Post, the New York Times, and many other media outlets. EDGI also uses the interview data to publish in peer-reviewed journals in order provide legitimacy to its work in a variety of institutional settings.[3]

Environmental Data Justice:

Though EDGI seeks to protect environmental agencies and federal environmental science from the Trump administration, it does not advocate a return to Obama-era liberalism. Rather, we have worked to build new social practices and analytical concepts that can remake existing environmental data and governance practices. Environmental data justice (EDJ) aims to move beyond practices of documenting harm that have been prevalent, albeit necessary, among environmental justice and critical data activism and scholarship (Tuck 2009). Instead, this framework centers itself around the creation and implementation of new visions and prototypes for anti-oppressive environmental data structures. The concept and practice of environmental data justice emerged from internal conversations about the prior politics of environmental data and the need to critically examine who collects and manages data and whose interests existing databases serve. EDGI members recognize that environmental justice activists have long struggled with the inadequacies and absences of state and industry-led environmental monitoring practices, even as EJ groups often must depend on that same data to make justice claims legible to the state. EDGI seeks to continue in the tradition of grassroots environmental monitoring projects, like the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, by bringing environmental justice concerns together with critical data studies.[4] One example of this is Data Together, which aims to develop community-based and decentralized models of data stewardship. Data Together emerged in part from conversations and reflections during the DataRescue project to embrace a shift from primarily preserving existing datasets towards also building new social and technical infrastructures that enable alternative relationships to data (Walker et al. forthcoming).

As part of developing the concept of EDJ, EDGI organized a mini-conference, “Enacting Environmental Data Justice,” in Boston in August 2017, prior to the annual meeting of the Society for the Social Studies of Science. Sixty attendees worked in small groups and overall plenary sessions to build new concepts and formulations to inform a manifesto and agenda for future work in this area (EDGI 2017). This focus spurred EDGI to draw inspiration from both academic and grassroots groups, such as Data 4 Black Lives, which met in Cambridge, MA November 18–19, 2017; Detroit Digital Justice Coalition; and to present at the May 2018 Data Justice conference in Cardiff, Wales, which is “an international conference exploring research on, and practices of, social justice in an age of datafication.” EDJ is currently partnering with TRU to plan a public facing series of Data Justice-related presentations, prioritizing grassroots over university-based groups but including both.

Capacity and Governance:

The Capacity and Governance Working Group has provided commentary and critical analysis of EPA activities, Congressional bills, and other government activity, and submits public comments on proposed EPA policy and practice. For example, on the night of Scott Pruitt’s inaugural speech as EPA Administrator, EDGI researchers gathered online to collectively annotate the speech transcript, providing historical and sociological context for Pruitt’s statements and rhetoric. EDGI’s annotation was published within a few days, reported on in Newsweek, and included as a piece in Environmental Health News (the definitive daily newsfeed in its field) with an additional EDGI commentary (DiCamillo 2017; Brown, Wylie, and Sellers 2017). Other EDGI reports stemming from this working group include a white paper on H.R. 1430, the Honest and Open New EPA Science Treatment (HONEST) Act of 2017, more commonly referred to as the “Secret Science Act.”

‘ In that white paper, we argue that H.R. 1430 would reduce EPA’s ability to develop environmental protections by limiting the kinds of scientific research the EPA could rely on. For example, it would block the EPA from considering scientific studies that are not reproducible (including studies of socio-natural disasters) or that include private (though anonymized) medical records. H.R. 1430 was passed by the House of Representatives in 2017. As of July 2018, it has emerged in modified form as one of EPA’s own proposed rules (Wittenberg 2018), about which EDGI has released a comment (Underhill et al. 2017). EDGI also gave oral public comments at an EPA hearing on proposed amendments to the Risk Management Program mandated by the Clean Air Act. During 2017, EDGI member Sarah Lamdan, an Associate Professor and law librarian at CUNY School of Law, led EDGI’s Freedom of Information Request (FOIA) efforts, in collaboration with other environmental advocacy groups, like the Sierra Club.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF EDGI’S STRUCTURE

EDGI benefited from a political opportunity structure in which many diverse social movements were strategizing how best to engage in resistance. With concerns about the Trump administration’s future plan, many diverse organizations found common ground to address grievances around administration attacks on the environment. EDGI was able to quickly form and offer an avenue for other groups to easily join in. EDGI’s co-founders were well-connected to varied disciplines and many types of organizations, enabling them to quickly call on colleagues to join in the work, with an appeal to the urgency of the project. What resulted was a unique coalition of diverse actors that do not often interact with each other, including social scientists, biologists, toxicologists, historians, archivists, librarians, computer programmers, and community activists. This coalition was able to integrate insights from multiple social movements and academic fields to create a more cohesive response to threats from the Trump administration and to proactively conceptualize more just social structures and technical infrastructures. EDGI’s strengths center on the combination of skills and disciplines that was needed for the nature of this multifaceted work.

EDGI’s success as a rapidly-formed social movement organization is largely a result of its participatory, horizontal, and transparent organizational form. In addition, as discussed above, the founders had a variety of current and past face-to-face collaborations. Further, the three main organizations and centers that helped launch EDGI were themselves well-connected to people and organizations, enabling quick expansion. The organizational form builds on EDGI members’ experience with collaborative and activist organizing, providing multiple opportunities for involvement, yet at the same time allowing for differing levels of commitment from members As we wrote earlier in this article, the founders had a variety of current and past face-to-face collaborations. Further, the three main organizations and centers that helped launch EDGI were themselves well-connected to many people and organizations, enabling quick expansion. The network of geographically dispersed individuals and institutions is linked through weekly steering committee meetings that are open to all members, via video-conferencing, as well as frequent meetings of individual working groups. Each working group reports to the whole body, yet has enough autonomy to carry out its tasks, thus enabling the best use of different strengths and disciplinary trainings. A number of faculty members were able to involve graduate students, adding to the personnel power. Librarians at several universities, a group attentive to the threats posed by the current administration to data integrity and continuity, made their skills and facilities available for DataRescue events. Some foundations were quick to offer funding, and data storage firms were able to supply in-kind donations. Journalists, themselves under attack by the Trump administration, also extensively covered EDGI activities.

It may be that EDGI’s interest in protecting environmental data and modus operandi have limited our ability to recruit beyond the relatively privileged, digitally skilled and majority White professional academics whose work for EDGI can often dovetail with their primary professional interests and commitments. This requires us to direct a lot of necessary time and effort towards protocols that prioritize the hiring and recruitment of members from traditionally marginalized backgrounds and more direct engagement with low-income, rural, or minority communities who may be the most affected by changing policies or data availability. We also realize that some EJ groups may not be as interested as we are in archiving state environmental data, since the state is often much more of a daily opponent to them. EDGI’s work is in some ways paradoxical in that it seeks to protect the state, even as we argue that the EPA and other state functions have been problematic for environmental justice causes, even in the most liberal democratic administrations.

Another paradox which EDGI navigates is how it advocates for open-source and transparently developed software but still relies on corporate platforms like Zoom, Slack, and Google in order to communicate efficiently and conduct other administrative activities. On Slack and Google, although we keep mostly transparent channels and documents, some working groups require private channels because of sensitive information or discussions. Since this information is kept on the corporate servers of platform services that operate on a freemium model, technical functionality may allow an employee at Slack or Google to access messages that members of EDGI’s steering committee may not even be able to. Moreover, as these services are free to use with the option to subscribe and pay for more features, they are subject to the business models of companies like Google where they may sell the data we generate to marketing firms (Vaidhyanathan 2012). Although we do not condone these practices as they present issues related to the practice of full consent and may facilitate state or corporate surveillance (Dencik, Hintz, and Cable 2016; Redden and Brand 2017), we recognize trade-offs we have made in EDGI for the affordances of these tools in order to attain our political goals.

While a centralized steering committee is essential for coordinating the various activities, it is hard to provide leadership and direction in areas that the Steering Committee may have limited technical or political knowledge. It is also possible that the democratic and horizontal structure can lead to more time spent on processing concerns, thus slowing down some areas of work. To help deal with time availability issues of an all-volunteer organization, two recent foundation grants (totaling $700,000 over a two year period) have given new flexibility to hire regular paid positions. As with any social movement organization of this size, funding is a difficult problem, with much organizational energy diverted to searching for funds for expensive but needed items such as web-monitoring software license fees. Also, EDGI’s administrative work related to funding requires leadership to maintain secure and private interactions that are separate from the online platforms open to all members. Tasks such as budgeting, grant development, and communication with our fiscal sponsors are thus less transparent than other EDGI work. As a result, the average member does not see the large amount of the administrative labor.

CONCLUSION

EDGI develops forms of democratic environmental governance that we hope can be extended in a more liberal regime, and certainly in a new society, based on the following vision statement:

We envision a future in which justice and equity are at the center of environmental, climate, and data governance. Governing agencies and industries will be held accountable through transparent, collaborative, community-centered environmental research, technology, and decision-making. We seek to realize a world that creates and maintains healthy, just, bountiful, and beautiful environs in which people thrive.

Though only a little over a year and a half old as of this writing, EDGI has carried out a tremendous amount of resistance to the Trump administration and is committed to continuing to respond to the threats posed by its anti-science and anti-environmental policies and developing more just environmental decision-making and data practices. EDGI plans to continue developing tools and practices that other scholar-activists can use and develop, for example, carrying out parallel data rescue projects in other areas such as health care or at state and local levels. We also expect to develop new forms of democratic, participatory environmental governance and data justice that will influence policy-makers in subsequent administrations, support academic research, and empower community organizations. While supporting EPA staff who are trying to do their work of environmental protection in a hostile environment, where hundreds of staffers have left already, EDGI is well aware that the EPA has been an imperfect agency. Even under the Obama administration, prior to the Republican takeover of the House in 2010 and the full Congress in 2014, EPA’s budget was cut and its regulatory power curtailed. There was widespread criticism of EPA by environmental activists for the agency’s hesitancy to take stronger regulatory stances that could have occurred even without full Democratic control of Congress. We point this out in order to clearly state that our goals for democratic environmental governance go much further than a return to the pre-Trump years. Beyond EDGI’s creative forms of resistance to current threats, the organization seeks to incorporate justice-oriented social theories and critique in its organizational form and practices, so as to proactively imagine a better society.

Acknowledgments

* We are grateful to the David & Lucile Packard Foundation and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation for support, and to Public Lab for fiscal sponsorship. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32ES023769. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We are also grateful for the thoughtful feedback and suggestions from three anonymous reviewers.

Footnotes

Volunteers on the communications team regularly compile articles, blog posts, television stories, and radio broadcasts that mention EDGI. A full list of EDGI’s media coverage can be found at https://envirodatagov.org/coverage.

For example, Bus Turnaround Coalition is a public transportation advocacy group that creates digital tools to generate bus report cards and ultimately improve New York City public bus transit (http://busturnaround.nyc).

One article has been published in Environmental Justice, two in American Journal of Public Health, two others were recently submitted, and further articles are in preparation.

The Bucket Brigade conducts air monitoring to produce data not gathered by state and federal regulatory agencies and press for greater controls over polluters.

REFERENCES

- Agyeman Julian, Schlosberg David, Craven Luke, and Matthews Caitlin. 2016. “Trends and Directions in Environmental Justice: From Inequity to Everyday Life, Community, and Just Sustainabilities.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 41 (1): 321–40. 10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin Emily. 2017. “Inside the Scientists’ Quiet Resistance to Trump.” The New Republic, February 24, 2017 https://newrepublic.com/article/140731/inside-scientists-quiet-resistance-trump. [Google Scholar]

- Bellacasa Maria Puig de la. 2011. “Matters of Care in Technoscience: Assembling Neglected Things.” Social Studies of Science 41 (1): 85–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benford Robert D., and Snow David A.. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 611–639. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman Andrew, Gehrke Gretchen, Rinberg Toly, Nost Eric, and Aizman Anastasia. “Assessment of Removals and Changes in Access to Resources on the EPA’s ‘Climate and Energy Resources for State, Local, and Tribal Government’ Website” 2017. https://envirodatagov.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/AAR-5-EPA-State-Local-Climate-Energy-171018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle Maree, and Parry Ken. 2007. “Telling the Whole Story: The Case for Organizational Autoethnography.” Culture and Organization 13 (3): 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Phil, Morello-Frosch Rachel, Zavestoski Stephen, Senier Laura, Altman Rebecca, Hoover Elizabeth, Sabrina McCormick, Brian Mayer, and Adams Crystal. 2010. “Field Analysis and Policy Ethnography: New Directions for Studying Health Social Movements” In Banaszak-Holl Jane, Levitsky Sandra, and Zald Mayer (eds.) Social Movements and the Development of Health Institutions. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Phil, Wylie Sara, and Sellers Christopher. 2017. “Commentary: De-Coding Pruitt.” Environmental Health News, March 3, 2017 https://www.ehn.org/commentary_de-coding_pruitt-2497220409.html. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard Robert D. 2008. Dumping In Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality, Third Edition New York: Westview Press; http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=1212681. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier Darlene, and Kennedy Eric B.. 2016. The Rightful Place of Science: Citizen Science. Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- Chowkwanyun Merlin. 2011. “The New Left and Public Health The Health Policy Advisory Center, Community Organizing, and the Big Business of Health, 1967–1975.” American Journal of Public Health 101 (2): 238–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke Adele E., and Star Susan Leigh. 2008. “The Social Worlds Framework: A Theory/Methods Package.” The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies 3: 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Cordner Alissa, Brown Phil, and Richter Lauren. 2018. “Environmental Chemicals and Public Sociology: Engaged Scholarship on Highly Fluorinated Compounds” Presentation at 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dencik Lina, Hintz Arne, and Cable Jonathan. 2016. “Towards Data Justice? The Ambiguity of Anti-Surveillance Resistance in Political Activism.” Big Data & Society 3 (2): 205395171667967 10.1177/2053951716679678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson Janis L., and Bonney Rick. 2012. Citizen Science: Public Participation in Environmental Research. Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DiCamillo Nathan. 2017. “Scott Pruitt’s First Speech to the EPA, Annotated by Environmental Scholars.” Newsweek, February 21, 2017 https://www.newsweek.com/scott-pruitt-epa-speech-graded-annotated-scholars-560822. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon Lindsey, Sellers Christopher, and EDGI. 2017. “Environmental Data and Governance in the Trump Era.” Social Science Research Council. December 5, 2017 https://items.ssrc.org/environmental-data-and-governance-in-the-trump-era/. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon Lindsey, Sellers Christopher, Underhill Vivian, Shapiro Nicholas, Jennifer Liss Ohayon Marianne Sullivan, Brown Phil, Harrison Jill, Wylie Sara, and “EPA Under Siege” Writing Group. 2018. “The Environmental Protection Agency in the Early Trump Administration: Prelude to Regulatory Capture.” American Journal of Public Health 108 (S2): S89–S94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon Lindsey, Walker Dawn, Shapiro Nicholas, Underhill Vivian, Martenyi Megan, Wylie Sara, Lave Rebecca, Murphy Michelle, Brown Phil, and Environmental Data and Governance Initiative. 2017. “Environmental Data Justice and the Trump Administration: Reflections from the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative.” Environmental Justice 10 (6): 186–92. 10.1089/env.2017.0020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon Lindsey, Lave Rebecca, Mansfield Becky, Wylie Sara, Shapiro Nicolas, Chan Anita, and Murphy Michelle. “Situating Data in the Trumpian Era: The Environmental Data and Governance Initiative” Annals of the American Association of Geographers. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Earl Jennifer, and Kimport Katrina. 2011. Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Earl Jennifer, Kimport Katrina, Prieto Greg, Rush Carly, and Reynoso Kimberly. 2010. “Changing the World One Webpage at a Time: Conceptualizing and Explaining Internet Activism.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 15 (4): 425–446. [Google Scholar]

- EDGI. 2017. “Towards an Environmental Data Justice Statement: Initial Thoughts.” Environmental Data & Governance Initiative. September 6, 2017 https://envirodatagov.org/towards-edj-statement/. [Google Scholar]

- EDGI 2018a. “Press Coverage: Member Op-Eds.” Environmental Data & Governance Initiative. 2018 https://envirodatagov.org/press/#op-ed. [Google Scholar]

- EDGI. 2018b. “Press Coverage.” Environmental Data & Governance Initiative. 2018 https://envirodatagov.org/press/. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson Leif, Sellers Christopher, Dillon Lindsey, Jennifer Liss Ohayon Nicholas Shapiro, Sullivan Marianne, Bocking Stephen, Brown Phil, Rosa Vanessa de la, and Harrison Jill. 2018. “History of US Presidential Assaults on Modern Environmental Health Protection.” American Journal of Public Health 108 (S2): S95–S103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frickel Scott, and Hess David J., eds. Fields of Knowledge: Science, Politics and Publics in the Neoliberal Age. Emerald Group Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Heeks Richard, and Renken Jaco. 2016. “Data Justice for Development: What Would It Mean?” Information Development 34 (1): 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann Andrew. 2017. Organizational Autoethnographies: Our Working Lives. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin Alan. 1995. Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise, and Sustainable Development. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kitschelt Herbert P. 1986. “Political Opportunity Structures and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies.” British Journal of Political Science 16 (1): 57–85. [Google Scholar]

- Klawiter Maren. 1999. “Racing for the Cure, Walking Women, and Toxic Touring: Mapping Cultures of Action within the Bay Area Terrain of Breast Cancer.” Social Problems 46 (1): 104–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lamdan Sarah. 2017. “Lessons from DataRescue: The Limitations of Grassroots Climate Change Data Preservation and the Need for Federal Records Law Reform.” U. Pa. L. Rev. Online 166: 231. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton Eric, and Friedman Lisa. 2017. “E.P.A. Contractor Has Spent Past Year Scouring the Agency for Anti-Trump Officials.” The New York Times, December 15, 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/15/us/politics/epa-scott-pruitt-foia.html. [Google Scholar]

- MacKendrick Norah. 2017. “Out of the Labs and into the Streets: Scientists Get Political” In Sociological Forum, 32:896–902. Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Martin John Levi. 2003. “What Is Field Theory?” American Journal of Sociology 109 (1): 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- McAdam Doug, McCarthy John D., and Zald Mayer N., eds. 1996. Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements: Political Opportunities, Mobilizing Structures, and Cultural Framings. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy John D., and Zald Mayer N.. 1977. “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 82 (6): 1212–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer David S., and Staggenborg Suzanne. 1996. “Movements, Countermovements, and the Structure of Political Opportunity.” American Journal of Sociology 101 (6): 1628–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Mohai Paul, Pellow David, and Roberts J. Timmons. 2009. “Environmental Justice.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 34: 405–430. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Kelly. 2008. Disrupting Science: Social Movements, American Scientists, and the Politics of the Military, 1945–1975. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Kelly, and Frickel Scott. 2006. The New Political Sociology of Science: Institutions, Networks, and Power. The University of Wisconsin Press; http://14.139.206.50:8080/jspui/handle/1/2163. [Google Scholar]

- Paris Britt, Lave Rebecca, and UCS Science Network. 2017. “Environmental Injustice in the Early Days of the Trump Administration.” Union of Concerned Scientists. July 20, 2017 https://blog.ucsusa.org/science-blogger/environmental-injustice-in-the-early-days-of-the-trump-administration. [Google Scholar]

- Pellow David N. 2000. “Environmental Inequality Formation: Toward a Theory of Environmental Injustice.” American Behavioral Scientist 43 (4): 581–601. [Google Scholar]

- Ray Raka. 1999. Fields of Protest: Women’s Movements in India. Vol. 8 University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Redden Joanna, and Brand Jessica. 2017. “Data Harm Record.” Data Justice Lab. 2017 https://datajusticelab.org/data-harm-record/. [Google Scholar]

- Rinberg Toly, Maya Anjur-Dietrich Marcy Beck, Bergman Andrew, Derry Justin, Dillon Lindsey, Gehrke Gretchen, Lave Rebecca, Sellers Chris, Shapiro Nick, Aizman Anastasia, Allan Dan, Britt Madelaine, Cha Raymond, Chadha Janak, Currie Morgan, Johns Sara, Klionsky Abby, Knutson Stephanie, Kulik Katherine, Lemelin Aaron, Nguyen Kevin, Nost Eric, Ouellette Kendra, Poirier Lindsay, Rubinow Sara, Schell Justin, Ultee Lizz, Upfal Julia, Wedrosky Tyler, Wylie Jacob, EDGI (2018, January 10). Pursuing A Toxic Agenda: Environmental Injustice in the Early Trump Administration. Retrieved from https://envirodatagov.org/publication/changing-digital-climate. [Google Scholar]

- Schussman Alan, and Earl Jennifer. 2004. “From Barricades to Firewalls? Strategic Voting and Social Movement Leadership in the Internet Age.” Sociological Inquiry 74 (4): 439–463. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers Christopher. 2017a. “Trump and Pruitt Are the Biggest Threat to the EPA in Its 47 Years of Existence.” Vox, July 1, 2017 https://www.vox.com/2017/7/1/15886420/pruitt-threat-epa. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers Christopher. 2017b. “How Republicans Came to Embrace Anti-Environmentalism.” Vox. April 22, 2017 https://www.vox.com/2017/4/22/15377964/republicans-environmentalism. [Google Scholar]