Abstract

Purpose:

P-glycoprotein (Pgp) antagonists have had unpredictable pharmacokinetic interactions requiring reductions of chemotherapy. We report a phase I study using tariquidar (XR9576), a potent Pgp antagonist, in combination with vinorelbine.

Experimental Design:

Patients first received tariquidar alone to assess effects on the accumulation of 99mTc-sestamibi in tumor and normal organs and rhodamine efflux from CD56+ mononuclear cells. In the first cycle, vinorelbine pharmacokinetics was monitored after the day 1 and 8 doses without or with tariquidar. In subsequent cycles, vinorelbine was administered with tariquidar. Tariquidar pharmacokinetics was studied alone and with vinorelbine.

Results:

Twenty-six patients were enrolled. Vinorelbine 20 mg/m2 on day 1 and 8 was identified as the maximum tolerated dose (neutropenia). Nonhematologic grade 3/4 toxicities in 77 cycles included the following: abdominal pain (4 cycles), anorexia (2), constipation (2), fatigue (3), myalgia (2), pain (4) and dehydration, depression, diarrhea, ileus, nausea, and vomiting, (all once). A 150-mg dose of tariquidar: (1) reduced liver 99mTc-sestamibi clearance consistent with inhibition of liver Pgp; (2) increased 99mTc-sestamibi retention in a majority of tumor masses visible by 99mTc-sestamibi; and (3) blocked Pgp-mediated rhodamine efflux from CD56+ cells over the 48 hours examined. Tariquidar had no effects on vinorelbine pharmacokinetics. Vinorelbine had no effect on tariquidar pharmacokinetics. One patient with breast cancer had a minor response, and one with renal carcinoma had a partial remission.

Conclusions:

Tariquidar is a potent Pgp antagonist, without significant side effects and much less pharmacokinetic interaction than previous Pgp antagonists. Tariquidar offers the potential to increase drug exposure in drug-resistant cancers.

Drug resistance is a major impediment to chemotherapy in many human cancers. P-glycoprotein (Pgp), encoded by the MDR-1 gene, is an energy-dependent efflux pump that lowers the intracellular concentrations of a variety of chemotherapeutic agents (1–4). Expression of the MDR-1 gene at levels found in many clinical tumor samples can confer multidrug resistance in vitro, suggesting MDR-1/Pgp–mediated drug resistance is clinically relevant.

The anthranilic acid derivative, tariquidar (XR9576), is a potent and selective Pgp inhibitor being developed clinically for the treatment of multidrug resistant tumors. At concentrations of 25 to 80 nmol/L (16–52 ng/mL), tariquidar restores the sensitivity of many multidrug-resistant human tumor cell lines in vitro by inhibiting Pgp-mediated drug efflux (5–7). The duration of action of tariquidar is superior to other inhibitors tested, persisting for at least 22 hours after removal of drug from the culture medium. Tariquidar uptake into cells is independent of Pgp expression, and data suggest tariquidar is not a transport substrate of Pgp and that tariquidar-mediated inhibition of Pgp transport is noncompetitive.

First generation Pgp inhibitors had potent pharmacologic effects and toxicity (4, 8–11). Third generation Pgp inhibitors, such as tariquidar, specifically target Pgp and seem to have minimal toxicity that is not dose limiting. To determine the optimal dose of vinorelbine in combination with tariquidar, we conducted a phase I study with a fixed dose of tariquidar in combination with vinorelbine.

Patients and Methods

Patient selection.

After obtaining verbal and written informed consent, 26 patients that satisfied standard enrollment criteria were enrolled on the trial that had been reviewed and approved by the National Cancer Institute-Institutional Review Board. Exclusion criteria (Supplementary Information) did not prevent the entry of any patient, although one patient found to have a brain metastasis after the baseline 99mTc Sestamibi scan did not receive vinorelbine. Thus, the toxicity of tariquidar plus vinorelbine was evaluated in only 25 patients.

Drug supply and treatment schema.

Xenova, Ltd manufactured Tariquidar. This was an open-label single arm phase I dose escalation trial to establish the maximum tolerated dose and dose-limiting toxicity and a recommended phase II dose of vinorelbine administered i.v. as a 15-min infusion on days 1 and 8 with tariquidar, every 21 d, with tariquidar administered over 30 min just before the vinorelbine. The initial vinorelbine dose was 15 mg/m2 on both days 1 and 8 (total dose, 30 mg/m2). Additional levels evaluated included 20 and 22.5 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Standard definitions were used for maximum tolerated dose, maximum administered dose, and dose-limiting toxicity. Dose modifications were based on the toxicity from the previous cycle and intrapatient dose escalations were allowed (Supplementary Information). Toxicity assessments were done each cycle and tumor evaluations every two cycles.

Pharmacodynamics: Rhodamine efflux from CD56+ cells.

Measurement of rhodamine efflux from circulating CD56+ cells exploits the high levels of expression of Pgp in CD56+ natural killer cells and has been previously described (refs. 12, 13; Supplementary Information).

Vinorelbine pharmacokinetics.

Vinorelbine pharmacokinetics was studied on the first treatment cycle after administration of the agent alone (day 1) and in combination with tariquidar (day 8). Plasma samples were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection as previously described (ref. 14; Supplementary Information).

Tariquidar pharmacokinetics.

Tariquidar pharmacokinetics was studied in detail with plasma samples assayed as previously described (Supplementary Information; ref. 15).

99mTc-Sestamibi scanning.

All patients consented to undergo two 99mTc-sestamibi scans and these were analyzed as previously described (16–18). Twenty-five patients had two 99mTc-sestamibi scans and received protocol therapy.

Using the corrected time-activity curves, areas under the curves (AUC) were calculated for 0 to 3 h for each time-activity curve using the linear trapezoidal method. To compare 99mTc-sestamibi uptake at baseline to that after tariquidar administration, a ratio of the AUC0–3 hour in tissue or tumor to the AUC0–3 hour heart was generated to yield tissue: heart AUC0–3 hour. Tissue and tumor AUCs were normalized to the heart muscle AUC because the heart contains relatively little Pgp and uptake should not be affected by tariquidar (11, 12).

Response evaluation.

Standard criteria were used to evaluate responses (Supplementary Information).

Results

Patient characteristics.

Table 1 summarizes the diagnosis, performance status, age, and prior therapy of the 25 patients enrolled and treated on the trial. All patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 2 or better. The median number of prior regimens was 2, with a mean of 2.5. The median number of prior agents was 4, with a mean of 4.2. Excluding immune therapies, the median number of conventional chemotherapy agents for the study patients was 4, with a mean of 3.5. Sixteen of the 18 patients with a diagnosis other than renal cell carcinoma had been previously treated with at least one natural product known to be a substrate for Pgp: doxorubicin (11 patients), paclitaxel (9 patients), a Vinca alkaloid (6 patients), and etoposide (5 patients).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Disease | |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 7 |

| Breast cancer | 5 |

| Adrenocortical cancer | 4 |

| Ovarian cancer | 3 |

| Basal cell cancer | 1 |

| Cervical cancer | 1 |

| Ewing’s sarcoma | 1 |

| Melanoma | 1 |

| Parotid cancer | 1 |

| Small cell lung cancer | 1 |

| ECOG performance status | No. of patients |

| 0 | 8 |

| 1 | 15 |

| 2 | 2 |

| Age range (y) | No. of patients |

| 18–30 | 1 |

| 31–50 | 10 |

| 51–80 | 14 |

| Prior therapy (no. of regimens) | No. of patients |

| 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 7 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 2 |

| ≥6 | 1 |

| Prior therapy (no. of agents) | No. of patients |

| 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 7 |

| >6 | 5 |

NOTE: Excludes one patient with bladder cancer enrolled but not treated. All seven patients with renal cell carcinoma had been treated with immune therapies; only two had received conventional chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil alone or in combination with cisplatin).

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Dose escalation.

The tariquidar dose was fixed at 150 mg. Table 2 presents the dose escalation for vinorelbine and the associated toxicities. The starting vinorelbine dose was 15 mg/m2. Patients were also enrolled at dose levels using 20 and 22.5 mg/m2 of vinorelbine. A total of 77 cycles of tariquidar in combination with vinorelbine were administered to 25 patients with a median of 2 cycles per patient, a mean of 3.1 and a range of 1 to 10. Seven patients received four or more cycles. Sixty-eight of the 77 cycles were given at a dose of 20 mg/m2 or greater. Twenty-four of the 25 patients received at least 1 cycle at 20 mg/m2 either initially or after an intrapatient dose escalation; 20 patients received at least two cycles at a dose of 20 mg/m2 or greater. The trial allowed for intrapatient dose escalation so that in addition to the 3 starting doses, some patients also received vinorelbine doses of 25, 30, 35, and 40 mg/m2. One patient with adrenocortical cancer received one cycle each of 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 mg/m2 vinorelbine while receiving intermittent ketoconazole (2 of 3 weeks, excluding the week surrounding therapy) and again after discontinuing the ketoconazole. A second patient with adrenocortical cancer was treated for a total of six cycles with 15, 20, 25, 30, 30, and 35 mg/m2. We have previously noted in other studies that patients with adrenocortical cancer, especially those whose tumors are hormone producing, often tolerate higher doses of chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Dose escalation schema and toxicities in first tariquidar + vinorelbine cycle

| Dose level | No. of patients enrolled | Toxicity | Grade 3 toxicities (no. of patients) | Grade 4 toxicities (no. of patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 mg/m2 (d1, d8) | 4 | Diarrhea (1) | ||

| Hypertension (1) | ||||

| Infection (1) | ||||

| Vomiting (1) | ||||

| Anemia (1) | ||||

| Hypocalcemia (1) | ||||

| Leukopenia (1) | ||||

| Neutropenia (1) | ||||

| 20 mg/m2 (d1, d8) | 14 | MTD | Deep venous thrombosis (1) | Infection/sepsis (1) |

| Dyspnea (2)* | Hypotension (1)† | |||

| Myalgia (1) | Leukopenia (1) | |||

| Anemia (1) | ||||

| Elevated alkaline phosphatase (1) | ||||

| Neutropenia (2) | ||||

| Prolonged ptt (1) | ||||

| 22.5 mg/m2 (d1, d8) | 7 | DLT | Abdominal pain (1) | |

| Anorexia (1) | ||||

| Other (Tumor) pain (1) | ||||

| Leukopenia (3) | ||||

| Neutropenia (3) |

Abbreviations: MTD, maximum tolerated dose; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity.

In two patients with end-stage disease including pleural effusion.

In do not resuscitate setting.

Toxicities.

Only 1 of 7 patients enrolled at the 22.5 mg/m2 vinorelbine dose level experienced dose-limiting toxicity in the first cycle (vinorelbine alone on day 1 and tariquidar + vinorelbine on day 8; Table 2). This patient had grade 3 nonhematologic toxicities consisting of abdominal pain and anorexia. The other 6 patients received a second cycle (tariquidar + vinorelbine on days 1 and 8) at the same vinorelbine dose. Of these six patients, two experienced dose-limiting neutropenia (Table 3). The study design specified that determination of maximum administered dose, and maximum tolerated dose would be based on dose-limiting toxicity observed during the first treatment cycle; however, we felt in retrospect that the first cycle may not have been the best choice because only one of the two vinorelbine doses was administered with tariquidar. Although vinorelbine doses of 22.5 mg/m2 or higher were administered in 36 cycles, and multiple cycles were tolerated by 6 patients, we felt that 2 dose-limiting toxicities in the 6 patients enrolled at the 22.5 mg/m2 vinorelbine dose level during the second cycle when both vinorelbine doses were administered together with tariquidar, represented excessive toxicity. Thus, we identified 20 mg/m2 as the maximum tolerated dose without filgrastim and as the recommended phase II dose. None of the 14 patients started at the 20 mg/m2 dose level had grade 4 neutropenia in the first cycle, although 2 had grade 3 neutropenia. However, grade 3 (7) or grade 4 (4) neutropenia was noted in 11 of 32 cycles given at 20 mg/m2, and in 12 of 36 cycles at higher doses (7 grade 3 and 5 grade 4). All other toxicities are summarized in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S1.

Table 3.

Toxicities in cycles other than first tariquidar + vinorelbine cycle

| Dose level | Patients receiving this dose | Cycles at this dose | Grade 3 toxicities (no. of events/no. of patients) | Grade 4 toxicities (no. of events/no. of patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 mg/m2 (d1, d8) | 3 | 5 | Dehydration (1/1) | Neutropenia (1/1) |

| Depression (1/1) | ||||

| Neutropenia (1/1) | ||||

| 20 mg/m2 (d1, d8) | 12 | 18 | Abdominal pain (1/1) | Neutropenia (4/3) |

| Anorexia (1/1) | ||||

| Cellulitis (1/1) | ||||

| Constipation (1/1) | ||||

| Fatigue (2/2) | ||||

| Illeus (1/1) | ||||

| Other pain (1/1) | ||||

| Anemia (2/1) | ||||

| Hyperglycemia (1/1) | ||||

| Neutropenia (5/3) | ||||

| 22.5 mg/m2 (d1, d8) | 9 | 14 | Constipation (1/1) | Neutropenia (3/3) |

| Neutropenia (3/2) | Prolonged PTT (1/1) | |||

| >22.5 mg/m2 (d1, d8) | 5 | 15 | Abdominal pain (2/2) | Anemia (1/1) |

| Fatigue (1/1) | Neutropenia (2/2) | |||

| Myalgia (1/1) | Prolonged PTT (1/1) | |||

| Nausea (1/1) | ||||

| Thrombosis (1/1) | ||||

| Neutropenia (1/1) | ||||

| Elevated sgot (1/1) | ||||

| Elevated ALT (1/1) | ||||

| Hyperglycemia (1/1) |

Tariquidar side effects recorded when tariquidar was administered alone in cycle 1 before the second 99mTc-Sestamibi study included the following: anorexia (2 events), blurred vision (1), constipation (1), diarrhea (1), fatigue (1), hypotension (2), insomnia (1), and pruritus (1).

Pharmacokinetics.

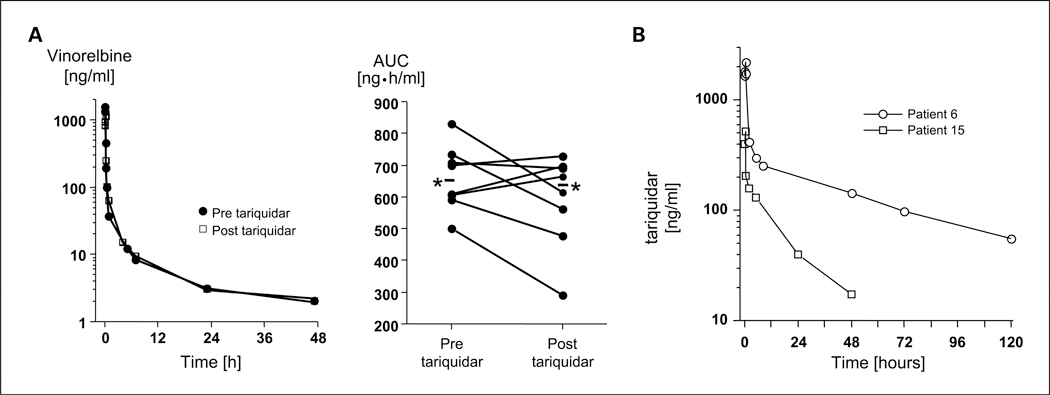

The vinorelbine pharmacokinetic parameters from the eight patients who had two complete sets of samples that were analyzed by the method that proved to be most sensitive are summarized in Table 4 and shown in Fig. 1. All of these patients received either 20 or 22.5 mg/m2 vinorelbine. There was no apparent effect of tariquidar on the disposition of vinorelbine. The median clearance of vinorelbine alone was 524 and 546 mL/min/m2 when administered with tariquidar. In this small group, we could also not discern a difference according to the patient’s weight, a possibility that was raised by the use of a fixed dose among all patients.

Table 4.

Vinorelbine pharmacokinetic parameters after an i.v. bolus of vinorelbine alone (pre) or after tariquidar (post)

| AUC0-∞(ng•h/mL) | Clearance (mL/min/m2) | t1/2 (h) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post |

| 15 | 511 | 304 | 652 | 1,097 | 18 | 23 |

| 16 | 838 | 566 | 398 | 589 | 48 | 21 |

| 17 | 603 | 540 | 553 | 617 | 21 | 43 |

| 19 | 758 | 786 | 495 | 477 | 37 | 36 |

| 20 | 756 | 811 | 496 | 462 | 36 | 58 |

| 22 | 625 | 724 | 600 | 518 | 22 | 23 |

| 23 | 844 | 700 | 444 | 536 | 19 | 51 |

| 24 | 635 | 675 | 591 | 555 | 28 | 21 |

| Median | 695 | 688 | 524 | 546 | 25 | 30 |

| Range | 511-844 | 304-811 | 398-652 | 462-1,097 | 18-48 | 21-58 |

NOTE: Patients 15, 16, and 17 received 20 mg/m2 vinorelbine; all others received 22.5 mg/m2.

Fig. 1.

A, vinorelbine pharmacokinetics were studied in the first treatment cycle after administration of the agent alone and in combination with tariquidar (days 1 and 8—alternating in patients). Frequent blood samples were obtained out to 120 h through a peripheral i.v. at a site distant from the infusion site. Left, the data in one patient. Right, data for all patients. * and accompanying line, the mean values for all patients. B, tariquidar concentration-time profiles from 2 patients treated with 150 mg of tariquidar, which resulted in >7-fold differences in drug exposure in these patients. The mean drug concentrations for all patients 24, 48, and 72 h after the dose of tariquidar without concomitant vinorelbine administration in cycle 1 were 121, 66, and 43 ng/mL, respectively, which are above the concentration of the drug required to restore chemosensitivity in Pgp-expressing tumor cell lines. The mean (±SD) clearance and terminal half-life of tariquidar were 287 ± 196 mL/min and 33.6 ± 13.5 h, respectively. The mean tariquidar plasma concentrations at 24 and 48 h were 119 and 79.4 ng/mL on cycle 1, and 121 and 69.5 ng/mL on cycle 2, respectively.

Tariquidar pharmacokinetic parameters summarized in Table 5 were highly variable. Figure 1 shows the tariquidar concentration-time profiles from 2 patients. Vinorelbine had no effect on tariquidar pharmacokinetics. The mean (±SD) clearance and terminal half-life of tariquidar were 287 ± 196 mL/min and 33.6 ± 13.5 hours, respectively. The mean tariquidar plasma concentrations at 24and 48 hours were 119 and 79.4ng/mL on cycle 1 and 121, and 65.9 ng/mL on cycle 2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Table 5.

Tariquidar pharmacokinetic parameters cycle 2: 150 mg i.v. over 30 min

| Patient | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC (mg•h/mL) | Clearance (mL/min) | Vdss (L) | Half-life (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,793 | 15.1 | 166 | 82.3 | 19.2 |

| 2 | 3,632 | 30.0 | 83 | 85.1 | 32.9 |

| 3 | 1,266 | 19.4 | 129 | 447 | 63.1 |

| 4 | 6,113 | 22.5 | 111 | 274 | 44.4 |

| 5 | 4,628 | 18.2 | 137 | 234 | 45.0 |

| 6 | 2,207 | 23.1 | 108 | 317 | 50.6 |

| 7 | 1,008 | 13.1 | 191 | 247 | 35.8 |

| 8 | 1,551 | 14.7 | 170 | 136 | 27.2 |

| 9 | 1,317 | 8.01 | 312 | 343 | 33.2 |

| 10 | 963 | 4.48 | 559 | 248 | 17.5 |

| 11 | 1,362 | 8.10 | 309 | 206 | 25.5 |

| 12 | 1,102 | 10.1 | 249 | 199 | 27.6 |

| 13 | 582 | 8.28 | 302 | 661 | 43.8 |

| 14 | 1,168 | 5.63 | 444 | 142 | 15.7 |

| 15 | 516 | 3.19 | 784 | 348 | 14.2 |

| 16 | 912 | 11.3 | 221 | 439 | 42.2 |

| 17 | 911 | 9.30 | 269 | 553 | 43.8 |

| 18 | 622 | 4.01 | 623 | 604 | 23.8 |

| Median | 1,217 | 10.7 | 235 | 261 | 33.0 |

Pharmacodynamics.

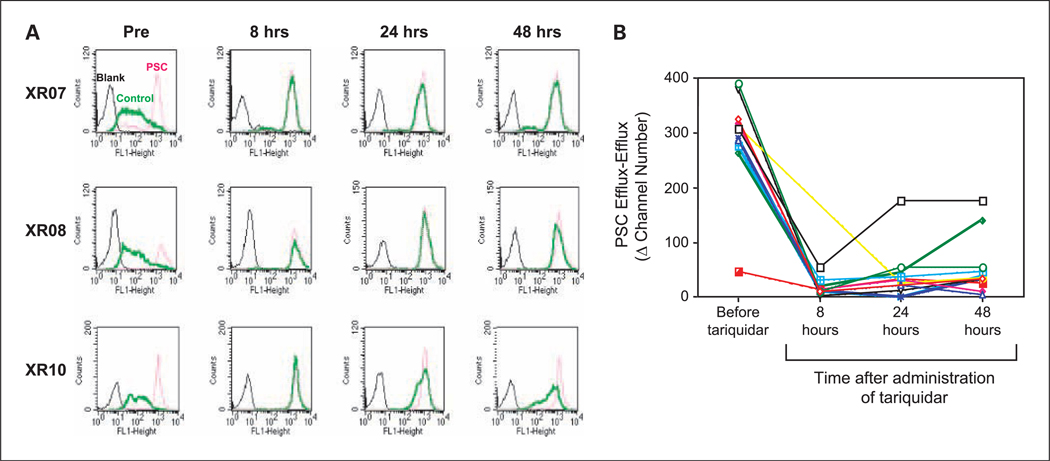

A significant component of this trial was the conduct of studies to examine the extent and duration of Pgp inhibition after a single 150-mg i.v. dose of tariquidar. Using circulating CD56+ cells, we were able to show that in the large majority of patients, rhodamine efflux from CD56+ cells was still blocked 48 hours after the administration of tariquidar. These data are summarized in Fig. 2. This assay exploits the high levels of Pgp expression in circulating CD56+ cells that allows them to efflux the Pgp substrate, rhodamine 123. A comparison is made between the inhibition of rhodamine efflux by tariquidar present in the patient’s blood and the inhibition by exogenously added PSC 833 (valspodar), a potent Pgp inhibitor. Even 48 hours after the administration of a single 150-mg i.v. dose of tariquidar, the marked inhibition of Pgp seen after the administration of Tariquidar is sustained.

Fig. 2.

Rhodamine efflux from CD56+ cells shows the extent and duration of Pgp inhibition after a single 150-mg i.v. dose of tariquidar. The inhibition of rhodamine efflux by the tariquidar present in the patient’s blood is compared with the inhibition by exogenously added PSC 833 (valspodar), a potent Pgp inhibitor. Rhodamine efflux is completely blocked by the addition of PSC833, and was similarly blocked by the tariquidar administered as part of the study. A, individual fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses obtained using CD56+ cells isolated from three study patients are shown. Rhodamine is rapidly extruded from CD56+ cells in the blood sample obtained before the administration of tariquidar (Pre), and very little remains inside the cells. In the Pre samples, there is a very large difference between the amount of rhodamine inside the cells in the portion of the sample that received no exogenous PSC833 (thick solid green line, middle), and the portion to which exogenous PSC833 was added (red dotted line, right). Black line, control endogenous fluorescence. By contrast, the difference in the 2 portions after the 8-, 24-, and 48-h administration of tariquidar i.v. is very small (thick solid green line and red dotted line are superimposed). In a majority of the blood samples obtained after the administration of tariquidar, the amount of rhodamine remaining inside CD56+ cells was similar to that in cells to which an excess of PSC833 was added exogenously. This indicates the i.v. administered tariquidar was as effective in blocking Pgp as an excess of PSC833 added exogenously. B, summary of the data for all patients. This panel shows plots of the difference (PSC Efflux − Efflux) between the amounts of rhodamine remaining inside the CD56+ cells after a period of efflux. The difference that is plotted is that between cells in the half of the sample that was treated with exogenous PSC833 before the efflux period (PSC Efflux) and that inside cells to which no exogenous PSC833 (Efflux) was added. Greater inhibition of rhodamine efflux by circulating tariquidar results in a smaller difference between the PSC Efflux and the Efflux values. Thus, increased inhibition of Pgp by tariquidar is reflected by the smaller values on the Y-axis. As can be seen, even 48 h after the administration of a single 150-mg i.v. dose of tariquidar, the differences in the large majority of samples is still very small indicating the inhibition of efflux even 48 h after the administration of tariquidar is similar to that achieved by freshly adding PSC833 exogenously.

99mTc-Sestamibi accumulations.

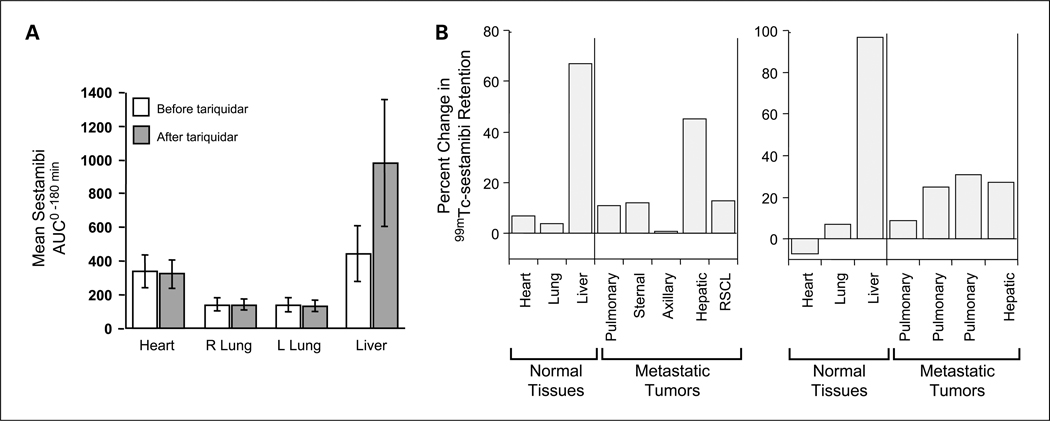

The in vivo efficacy of tariquidar was also shown by performing 99mTc-sestamibi scans in the patients enrolled on study as shown in Fig. 3. 99mTc-sestamibi, a radionuclide used in cardiac imaging studies, is a Pgp substrate and has been used as a functional imaging agent for the multi-drug resistance-1 phenotype. As previously reported, tariquidar enhanced 99mTc-sestamibi accumulation and retention in the liver of all but 2 patients with a mean change of +128%18. In 13 of the 17 patients with tumor masses visible by 99mTc-sestamibi, increased retention was noted after the administration of tariquidar, with increases of 36% to 263% seen in 8 patients. This provided convincing evidence of the existence of tariquidar-inhibitable 99mTc-sestamibi efflux in a large fraction of these drug resistant tumors (Supplementary Figs. S3–S5).

Fig. 3.

Effect of tariquidar on the accumulation of 99mTc-sestamibi. The in vivo efficacy of tariquidar was also shown by performing 99mTc-sestamibi scans obtained in the patients enrolled on study. 99mTc-sestamibi, a radionuclide used in cardiac imaging studies, is a Pgp substrate and has been used as a functional imaging agent for the multidrug resistance-1 phenotype. Baseline 99mTc-sestamibi scans were obtained, followed 48 to 96 h later by a second scan 1 to 3 h after the administration of tariquidar. A, evidence that inhibition of 99mTc-sestamibi efflux occurred only in organs expressing Pgp. The mean 99mTc-sestamibi AUC in the heart, right lung, left lung, and liver is shown for all study patients. Large differences were noted in Pgp-expressing liver but not in the heart nor in the lungs, organs with very little Pgp. B, the percent change in the 99mTc-sestamibi AUC0–180 after tariquidar in the two patients with measurable responses. The 99mTc-sestamibi AUC0–180 in the tumors of both patients was increased after the administration of tariquidar, albeit not to the extent seen in the normal liver that most likely had higher levels of Pgp. Left, the results are those of a patient with breast cancer who experienced a MR (8 prior regimens and 11 prior agents including 4 cycles of paclitaxel as a single agent 6 mo before enrollment, and 4 of Adriamycin as part of the CAF regimen 4 y before enrollment); right, the results in a patient with renal cell carcinoma who experienced a PR (see Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5).

Response evaluation.

A PR was observed in a patient with renal cell cancer and a MR (37%) in a patient with metastatic breast cancer (Supplementary Fig. S6; Fig. 3).

Discussion

We describe the results of a phase I study using the Pgp antagonist, tariquidar (XR 9576), in combination with vinorelbine. We determined that a vinorelbine dose of 20 mg/m2 on a day 1/day 8 schedule can be safely administered in combination with a single 150-mg dose of tariquidar. The single 150-mg dose of tariquidar was well-tolerated, inhibits Pgp-mediated rhodamine efflux from circulating cells CD56+ for at least 48 hours, inhibits the clearance of 99mTc sestamibi by the liver, and as previously reported, impairs of 99mTc sestamibi efflux from a large number of tumors (18). These findings are consistent with the observation that it is not a substrate for Pgp-mediated transport, and would be expected to have a longer duration of action. Importantly, given previous experience with earlier Pgp antagonists, 150 mg of tariquidar did not affect the pharmacokinetics of vinorelbine. We conclude that tariquidar is a potent Pgp antagonist, without significant side effects, and less pharmacokinetic interference than earlier antagonist. A single dose of 150 mg has a prolonged effect.

The results demonstrating a lack of an effect on vinorelbine pharmacokinetics are not surprising given evidence that exonerates tariquidar as an inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 enzymes implicated in liver-mediated drug metabolism (19). Although 11 cytochrome P-450s that can metabolize xenobiotics are expressed in the human liver, only 1A2, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4 seem to be involved in drug metabolism, and the drug-drug interactions of commonly used drugs (20). In vitro analysis using baculovirus expressing these individual human CYP450 subtypes found IC50 values for tariquidar that ranged from 7.1 to >100 micromolar, far higher than were achieved in our patients (19). However, although the results examining vinorelbine pharmacokinetics are unequivocal and indicate that tariquidar did not affect its disposition, one must reconcile this with the equally un-equivocal observation of a marked inhibition of Pgp-mediated liver efflux shown on the 99mTc-sestamibi studies. Given that 33% to 80% of administered vinorelbine is excreted into feces, whereas urinary excretion represents only 16% to 30% of total drug disposition, the majority of which is unmetabolized vinorelbine, it is reasonable to wonder why a greater effect on vinorelbine pharmacokinetics was not seen (21). A possible explanation might be found in our as yet incomplete knowledge of the drug specificity of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, and the possibility that transport across the liver could have been mediated by a transporter other than Pgp. A recent study that identified ABCC10/ MRP7 as a vinorelbine transporter provides a potential although unlikely candidate in the liver (22). Because ABCC10/MRP7 is expressed in liver at only very low levels, it would have difficulty rescuing a liver whose Pgp was inhibited; however, other ABC transporters may have helped. Also, we should stress that all our data showed is no change in the pharmacokinetics but makes no discrimination as to how excretion occurred. And because 16% to 30% of vinorelbine appears in the urine, we cannot exclude that urinary excretion increased after tariquidar administration, and this excretion, for example, could have been mediated by ABCC10/MRP7, because it is expressed at higher levels in the normal kidney compared with the liver. Finally, we would note that the observation that tariquidar effectively blocked rhodamine efflux from CD56+ cells for a period exceeding 48 hours indicates that P-glcyoproe-tin inhibition exceeded the median 25 hour half of vinorelbine in the absence of tariquidar. Thus, the lack of a tariquidar effect cannot be ascribed to insufficient inhibition.

In addition to tariquidar, other third generation antagonists have been studied. Zosuquidar (LY335979) a potent inhibitor containing a cyclopropyldibenzosuberane moiety has shown promising activity in vivo (23–25). Like tariquidar, zosuquidar does not seem to be a substrate for Pgp; although Pgp has a high affinity for zosuquidar with a Ka of 59 nmol/L. Clinical trials have reported that zosuquidar does not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of doxorubicin, etoposide, or paclitaxel; however, unlike tariquidar, a previous phase I study concluded “zosuquidar may inhibit vinorelbine clearance to a modest degree” (24). Interestingly with zosuquidar, the dose of vinorelbine felt to be tolerable was 22.5 mg/m2 i.v. weekly for 3 weeks every 28 days. Although the single dose is similar to that felt to be safe in the present study, a direct comparison cannot be made because the present study administered vinorelbine only on days 1 and 8. However, it seems safe to conclude that the dose of vinorelbine administered in combination with tariquidar was the same or possibly less than the dose administered with zosuquidar. Given the clear evidence of a lack of effect of tariquidar on the pharmacokinetics of vinorelbine, one must conclude that the dose-limiting neutropenia observed with the combination of tariquidar and vinorelbine is explained by tariquidar-mediated pharmacodynamic interaction most likely involving bone marrow stem or early precursor cells. That such an effect might be observed is not surprising, given the well-known fact that bone marrow stem cells express high levels of ABC transporters that are thought to protect them from toxins (26–31). But we would caution that one should not conclude that this pharmacodynamic interaction is confined to tariquidar because a similar interaction may have occurred with previous agents but was missed because there was also a pharmacokinetic interaction to explain the need for dose reductions. Finally, an indication of the prolonged activity of tariquidar can be found in the fact that unlike other antagonists, a one-time administration of tariquidar was sufficient to block Pgp.

Given the need to reduce the dose of vinorelbine administered as a consequence of the presumed pharmacodynamic interaction the question of how valuable combination therapy might be is a fair one to ponder. Although the answer can only come from a randomized trial, it is clear that an advantage for the combination with tariquidar will only be achieved if the tumor expresses Pgp. We have previously reported (18) increases of 36 to 263% in the accumulation of 99mTc-sestamibi, a surrogate for a chemotherapeutic agent, in renal cell carcinomas and adrenal cancers, tumors known to express Pgp, and also in breast cancers and other tumors. The increases observed in the patients shown in Fig. 3 represent increases over a 3-hour period and would translate into greater increases over time. These increases would more than offset the reduction in the dose of the chemotherapeutic agent but only in patients with tumors that express the Pgp “target.” As an aside, we would note that, if one accepts the central premise of the stem cell hypothesis—that successful therapy of cancer will occur only when we target the putative cancer stem cell—the value of an agent such as tariquidar would be in eradicating the surviving stem cells and may only be manifested in clinical measures such as progression-free survival and overall survival.

Several conclusions emerge from this study. The first is that tariquidar can be administered safely to patients with cancer in combination with a modestly reduced dose of vinorelbine. The need for a reduced dose of vinorelbine despite the lack of any pharmacokinetic interaction leads one to conclude that tariquidar has no effect on vinorelbine metabolism, a desirable attribute, but that it mediates a pharmacodynamic interaction at the level of the bone marrow, most likely a stem or an early precursor cell, an undesirable consequence, but one that can be remedied with growth factor support. Also clear from the present study is that some cells in the liver involved in the excretion of 99mTc-sestamibi and by inference chemotherapy agents, possess high levels of activity of an efflux pump that all evidence would conclude is Pgp. More importantly, in a subset of tumors expression of what can be safely concluded is a functional Pgp is observed. To the extent that this can be inhibited by tariquidar, it indicates that at least in some cancer cells, this efflux pump is very active and would undoubtedly mediate a reduced accumulation of drugs that are substrates for Pgp. The extent to which this reduction in intracellular drug concentration would affect drug efficacy depends on how narrow its intracellular margin is for activity—and for most of our drugs, including our newer agents this is usually very narrow. We would note that the planar 99mTc-sestamibi images obtained as part of this study underestimate the increase in accumulation because they cannot adequately subtract background and normal tissue in front and behind the tumor, so that a reduction in intracellular accumulation at least 2-fold or greater of 99mTc sestamibi and many chemotherapeutic agents is likely to occur in many tumors. A 2-fold reduction may be sufficient to significantly affect activity—for example, bcr-abl mutations in imatinibrefractory chronic myelogenous leukemia and c-KIT mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumor often affect drug binding ~ 2-fold as evidenced by both in vitro studies and clinical observations that increasing the dose by 50% to 100% often rescues activity (32–34). We would note that an increasing number of “novel targeted agents” are being recognized as Pgp substrates, and given their limited efficacy to date, the availability of an agent such as tariquidar will likely be of interest as attempts are made to increase their effectiveness. Finally, the results of the current study argue for the need to conduct clinical trials with drug resistance modulators such as tariquidar only with drugs that are proven substrates and only in patients likely to derive benefit from Pgp inhibition—those whose tumors express Pgp.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Although earlier clinical studies of P-glycoprotein (Pgp) inhibition as a means of reversing drug resistance failed to show dramatic improvement in clinical outcome, the inhibitors either had poor potency or interfered with the pharmacokinetics of the anticancer agent. This report describes the combination of vinorelbine with the anthranilic acid derivative tariquidar in 26 patients in a phase I trial design. Neutropenia was the principal toxicity observed, and 20 mg/m2 was identified as the maximum tolerated dose of vinorelbine in the combination. In surrogate studies, tariquidar showed excellent activity, including durable inhibition of Pgp in CD56+ cells ex vivo, and significant inhibition of sestamibi clearance from both liver and tumor in radionuclide imaging studies. Tariquidar had no effect on vinorelbine pharmacokinetics but may have affected its pharmacodynamics. This study suggests that tariquidar is a safe and potent Pgp inhibitor that should be moved forward to definitive clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wilma Medina for help in performing the rhodamine efflux assays and Leslyn Hermonstine for nursing assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Van Tellingen, commercial research support, Xenoba Ltd. The other authors disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Juliano RL, Ling V. A surface glycoprotein modulating drug permeability in Chinese hamster ovary cell mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1976; 455:152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fojo A, Akiyama S, Gottesman MM, Pastan I. Reduced drug accumulation in multiply drug-resistant human KB carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res 1985;45:3002–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck WT, Mueller TJ, Tanzer LR. Altered surface membrane glycoproteins in Vinca alkaloid-resistant human leukemic lymphoblasts. Cancer Res 1979;39:2070–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent trans- porters. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2:48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mistry P, Stewart AJ, Dangerfield W, et al. In vitro and in vivo reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by a novel potent modulator, Tariquidar. Cancer Res 2001; 61:749–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin C, Berridge G, Mistry P, Higgins C, Charlton P, Callaghan R. The molecular interaction of the high affinity reversal agent Tariquidar with P-glycoprotein. Br J Pharmacol 1999; 28:403–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox E, Bates SE. Tariquidar (XR9576): a P-glyco-protein drug efflux pump inhibitor. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2007;7:447–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferry DR, Traunecker H, Kerr DJ. Clinical trials of P-glycoprotein reversal in solid tumours. Eur J Cancer 1996;32:1070–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher GA, Sikic BI. Clinical studies with modulators of multidrug resistance. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1995;9:363–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradshaw DM, Arceci RJ. Clinical relevance of transmembrane drug efflux as a mechanism of multidrug resistance. J Clin Oncol 1998;16: 3674–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher GA, Lum BL, Hausdorff J, Sikic BI. Pharmacological considerations in the modulation of multidrug resistance. Eur J Cancer 1996;32: 1082–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham J, Bakke S, Rutt A, et al. A phase II trial of combination chemotherapy and surgical resection for the treatment of metastatic adreno-cortical carcinoma: continuous infusion doxorubicin, vincristine, and etoposide with daily mitotane as a P-glycoprotein antagonist. Cancer 2002;94:2333–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robey R, Bakke S, Stein W, et al. Efflux of rhodamine from CD56+ cells as a surrogate marker for reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated drug efflux by PSC 833. Blood 1999;93:306–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Tellingen O, Kuijpers A, Beijnen JH, Baselier MR, Burghouts JT, Nooyen WJ. Bio-analysis of vinorelbine by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J Chromatogr 1992;573:328–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart A, Steiner J, Mellows G, Laguda B, Norris D, Bevan P. PhaseItrial of XR9576 in healthy volunteers demonstrates modulation of P-glycoprotein in CD56+ lymphocytes after oral and intravenous administration. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:4186–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piwnica-Worms D, Chiu ML, Budding M, Kronauge JF, Kramer RA, Croop JM. Functional imaging of multidrug-resistant P-glycoprotein with an organotechnetium complex. Cancer Res 1993;53:977–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao VV, Chiu ML, Kronauge JF, Piwnica-Worms D. Expression of recombinant human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein in insect cells confers decreased accumulation of technetium-99m-sestamibi. J Nucl Med 1994;35:510–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal M, Abraham J, Balis FM, et al. Increased 99mTc-sestamibi accumulation in normal liver and drug-resistant tumors after the administration of the glycoprotein inhibitor, XR9576. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:650–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labrie P, Maddaford SP, Lacroix J, et al. In vitro activity of novel dual action MDR anthranilamide modulators with inhibitory activity on CYP-450 (Part 2). Bioorg Med Chem 2007; 15:3854–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh Sonu S Preclinical pharmacokinetics: An approach towards safer and efficacious drugs. Current Drug Metabolism. 2006;7:165–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowinsky E Microtubule-Targeting Natural Products. In Cancer Medicine Kufe D, Bast R, Hait W, Hong W, Pollack R, Weichselbaum R, Holland J, and Frei E (Editors). 2003; BC Decker Inc; 12(53):436. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bessho Y, Oguri T, Ozasa H, et al. ABCC10/ MRP7 is associated with vinorelbine resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep 2009; 21:263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morschhauser F, Zinzani PL, Burgess M, Sloots L, Bouafia F, Dumontet C. Phase I/II trial of a P-glycoprotein inhibitor, Zosuquidar.3HCl trihydrochloride (LY335979), given orally in combination with the CHOP regimen in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2007;48:708–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lê LH, Moore MJ, Siu LL, et al. Phase I Study of the multidrug resistance inhibitor zosuquidar administered in combination with vinorelbine in patients with advanced solid tumours. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2005;56:154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandler A, Gordon M, De Alwis DP, et al. A Phase I trial of a potent P-glycoprotein inhibitor, zosuquidar trihydrochloride (LY335979), administered intravenously in combination with doxorubicin in patients with advanced malignancy. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:3265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhary PM, Mechetner EB, Roninson IB. Expression and activity of the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Blood 1992;80: 2735–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raaijmakers MH. ATP-binding-cassette transporters in hematopoietic stem cells and their utility as therapeutical targets in acute and chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2007;21: 2094–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Jonge-Peeters SD, Kuipers F, de Vries EG, Vellenga E. ABC transporter expression in hematopoietic stem cells and the role in AML drug resistance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007;62:214–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sikic BI. Multidrug resistance and stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12 (11 Pt 1):3231–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donnenberg VS, Donnenberg AD. Multiple drug resistance in cancer revisited: the cancer stem cell hypothesis. J Clin Pharmacol 2005;45: 872–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lou H, Dean M. Targeted therapy for cancer stem cells: the patched pathway and ABC transporters. Oncogene 2007;26:1357–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noma K, Naomoto Y, Gunduz M, et al. Effects of imatinibvary with the types of KIT-mutation in gastrointestinal stromal tumor cell lines. Oncol Rep 2005;14:645–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zalcberg JR, Verweij J, Casali PG, et al. EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group, the Italian Sarcoma Group; Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group. Outcome of patients with advanced gastro-intestinal stromal tumours crossing over to a daily imatinib dose of 800 mg after progression on 400 mg. Eur J Cancer 2005;41: 1751–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu S, Xu H, Shah NP, et al. Detection of BCR-ABL kinase mutations in CD34+ cells from chronic myelogenous leukemia patients in complete cytogenetic remission on imatinib mesylate treatment. Blood 2005;105:2093–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.