Abstract

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations are predictive markers for response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The most common mutations, exon 19 short deletions and exon 20 point mutation (L858R), activate the tyrosine kinase and confer sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs. However, the function and sensitivity of rare mutations to EGFR-TKIs are unknown. In this study, we found five EGFR mutations out of 16 patients with NSCLC of African-American descent. The frequency of such mutations in this patient population appears to be significantly higher than previously reported. Two of them (N771GY and A767-V769dup) are rare insertion mutations located in exon 20. Using YFP-tagged EGFR mutants, we demonstrated that the mutations confer increased kinase activity, but no sensitivity to erlotinib at clinically available concentrations. In addition, we examined efficacy of PF00299804, an irreversible EGFR-TKI. Although the drug failed to show efficacy to T790M and S768N mutations, the exon 20 insertion mutations were sensitive to PF00299804. These data suggest that rare mutations in exon 20 are resistant to erlotinib but may be sensitive to irreversible inhibitors.

Keywords: EGFR, mutation, African American, EGFR-TKI

Introduction

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) has a key role in lung cancer tumorigenesis and progression. According to the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic/), more than 75 different EGFR tyrosine kinase domain residues have been reported to be altered in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The most common EGFR mutations are located in exon 19 (del 746–750) and exon 21 (L858R), and together represent more than 95% of the mutations found in this patient population (Mok et al., 2009; Rosell et al., 2009). These mutations activate the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain without the need of ligand stimulation, leading to activation of downstream signaling pathways. Of clinical interest is that the presence of these mutations in patients with NSCLC, predict sensitivity to treatment with reversible EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) such as gefitinib and erlotinib (Mok et al., 2009; Rosell et al., 2009; Mitsudomi et al., 2010). However, despite the initial high rate of response obtained with the use of reversible EGFR-TKIs, resistance to these drugs typically develops after 6–12 months of treatment. One of the bestknown mechanisms of resistance to these drugs is the development of a secondary EGFR resistant mutation such as the exon 20 T790M mutation, which has been reported in about half of patients with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib (Kobayashi et al., 2005; Kosaka et al., 2006).

EGFR mutations have been widely studied worldwide primarily in patients from East-Asian and White/ Caucasian descent. Numerous studies have shown significant racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of these mutations, which are found in 30–40% of Asian patients with NSCLC but in only 10–15% of their White/Caucasian patients. However, there is limited information available about EGFR mutations in African-American patients. In this study, we describe the case of an African-American patient with adenocarcinoma of the lung harboring a novel, erlotinib-resistant exon 20 mutation. We also present the results of a retrospective analysis of African-American patients with NSCLC seen at our institution, showing a significantly higher prevalence of EGFR mutations in this patient population than previously reported in the literature. (Yang et al., 2005; Krishnaswamy et al., 2009; Leidner et al., 2009). Additionally, we present data on the molecular and functional characterization of three exon 20 mutations found in African-American patients with NSCLC. The function and sensitivity to treatment of these mutations was examined using an YFP-EGFR-ICD-based assay that takes advantage of the lack of the extracellular domain of EGFR to study the kinase activity of the truncated EGFR.

Results

Case report

A 54-year-old African-American male with a distant history of very light smoking (four cigarettes per day for 2 years) presented in November 2007 with complaints of cough, right sided chest pain and dyspnea. A computed tomography scan of the chest revealed a right upper lobe pulmonary mass that was biopsied and diagnosed as lung adenocarcinoma. Further staging workup did not show other sites of metastatic disease and at the time of diagnosis he was considered to have a stage III NSCLC. He received induction chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel for a total of six cycles and was then referred to our institution in April 2008 for consideration of surgical resection. At the time of presentation to this institution, he was found to have a 4.7 by 6.9 cm right upper lobe mass (Figure 1a). Further workup with flexible bronchoscopy and right video assisted thoracoscopy revealed diffuse pleural studding throughout the right hemithorax, which precluded resection and the patient was then deemed as having T4 stage III-B disease. He was enrolled on a research protocol and received a total of four cycles of depsipeptide and flavopiridol achieving stable disease until April 2009, when he was found to have progression (Figure 1b). In June 2009, he received treatment with Erlotinib for a total of two cycles, but in August 2009 was found to have progressive disease (Figure 1c). More recently, the patient was enrolled in a phase II trial of sorafenib in patients with advanced refractory NSCLC (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of the chest showing the patient’s primary bulky mass in the right upper lobe at different points in time. (a) On presentation to our institution after six cycles of induction chemotherapy. (b) Progression after four cycles of flavopiridol and depsipeptide and before epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI) treatment. (c) Progression after 2 months of erlotinib treatment. (d) Stable disease with a decrease of 9% in longest diameter in the size of the primary right upper lobe mass after treatment with sorafenib.

DNA sequencing analysis revealed that the patient’s tumor sample harbored an EGFR mutation in exon 20 (N771GY) and wild-type (wt) KRAS (Figure 2). The height of mutated peaks suggests that the mutated allele might not be amplified. There was no EGFR mutation in exon 20 present in DNA extracted from peripheral mononuclear cells. To our knowledge, the EGFR N771GY mutation is novel and has not been reported in the literature or the COSMIC database. Immunostaining with EGFR antibody showed weak expression of EGFR (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Identification of a novel mutation. Upper panel, sequencing chromatogram from tumor sample showed double peaks. Small peak represent mutated allele. N771 was deleted and GY were inserted at this position. Middle panel showed results of sequencing analysis from the patient blood sample. There is no mutation in the normal sample. Lower panel, sequencing chromatogram from another patient showed A767-V769 duplication.

EGFR mutations in African-American patients

To expand on our findings in patients from African-American descent, we retrospectively analyzed the results of EGFR mutations from African-American patients with NSCLC seen at the Medical Oncology Branch of the National Cancer Institute from April 2007 to July 2010. We found 16 patients with these clinical characteristics who had had EGFR and KRAS mutation testing performed as part of their regular care. Of these patients, eight had a history of heavy smoking and eight were never or light smokers. We found a total of five EGFR somatic mutations out of 16 patients, including one exon 20 deletion-insertion (N771GY), one exon 20 insertion (A767-V769 dup) (Figure 2), two exon 19 deletions and one exon 21 point mutation (L858R). All of these mutations were found in patients who were never or light smokers, but no mutations were found in African-American patients with a previous history of smoking. Patient characteristics, clinical and pathological features are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features and EGFR status of African-American patients with NSCLC

| Patient number | Gender | Histology | Age at diagnosis |

Smoking history (pack-years) |

Stage | EGFR mutation |

EGFR (IHC) |

KRAS mutation |

Response to EGFR-TKI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-smokers | |||||||||

| NS-001 | Male | Ad | 52 | <1 | IIIB | N771GY | WP | WT | PD |

| NS-002 | Female | Ad | 64 | Never | IIIA | L858R | SP | WT | NA |

| NS-003 | Male | Ad | 50 | Never | IV | Del19 | NA | WT | PR |

| NS-004 | Female | Ad | 45 | Never | IV | WT | NA | WT | PD |

| NS-005 | Male | Ad | 48 | Never | IIIB | 767A–769V dup | NA | WT | NA |

| NS-006 | Male | Ad | 49 | Never | IV | WT | SP | WT | PD |

| NS-007 | Female | Ad | 71 | Never | IV | WT | NA | WT | PR |

| NS-008 | Female | Ad | 58 | Never | IV | Del19 | NA | WT | PR |

| Smokers | |||||||||

| S-001 | Female | NOS | 54 | 30 | IV | WT | WP | 13 (GGC > GAC) | NA |

| S-002 | Female | Ad | 58 | 35 | IV | WT | SP | WT | NA |

| S-003 | Female | SCC | 51 | 30 | IB | WT | NA | WT | NA |

| S-004 | Male | NOS | 68 | 50 | IV | WT | NA | WT | PD |

| S-005 | Male | NOS | 49 | 15 | IV | WT | NA | WT | PD |

| S-006 | Female | Ad | 58 | 35 | IV | WT | NA | WT | NA |

| S-007 | Male | Ad | 73 | 50 | IIIB | WT | NA | NA | NA |

| S-008 | Female | Ad | 65 | 50 | IIIB | WT | NA | 12 (GGT > TGT) | NA |

Abbreviations: Ad, adenocarcinoma; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NA, not assessable; NOS, nonotherwise specified; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SP, strong positive; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; WP, weak positive; WT, wild type.

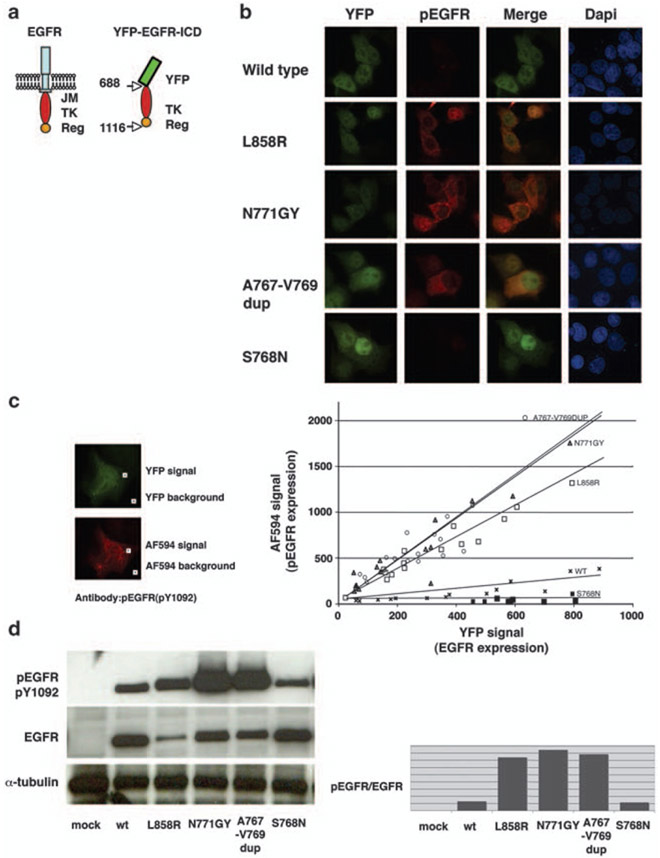

Augmented autophosphorylation of N771GY and A767-V769dup mutants

To further investigate the molecular and functional characteristics of the exon 20 mutations found in African-American patients, we used an YFP-EGFR-ICD-based assay. We introduced the N771GY mutation into the wt YFP-EGFR-ICD expression vector. MCF7 breast cancer cells were transfected with the plasmids encoding wt or mutant YFP-EGFR-ICD. The wt YFP-EGFR-ICD and the mutant L858R YFP-EGFR-ICD were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Cells were fixed 24 h after transfection and immunostained with a phosphorylation specific primary antibody against EGFR pY1092, followed by a secondary antibody conjugated with AF-594 (red fluorescence). YFP signal was used as a transfection marker. Non-transfected MCF7 cells did not show detectable levels of phospho-EGFR (pY1092). Wt YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected MCF7 cells showed undetectable or low levels of pY1092. In contrast, pY1092 was prominent in the mutant L858R YFP-EGFR-ICD and N771GY YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected MCF7 cells (Figure 3b). We quantified pY1092 signal through comparison of the intensity of YFP green signals with pY1092 red signals. As shown in Figure 3c graph, autophosphorylation of EGFR (pY1092) was increased in L858R and N771GY cells. Moreover, Y1092 autophosphorylation was more prominent in the N771GY than the L858R mutant cells. The microscopic observations were confirmed by western blotting (Figure 3d). We also introduced the mutations A767-V769dup and S768N into the wt YFP-EGFR-ICD. The A767-V769dup mutant, which we found in another African-American patient in our series (Table 1), showed a strong Y1092 autophosphorylation, akin to the N771GY mutant. In contrast, the S768N mutant reported in an African-American patient by another group (Leidner et al., 2009), did not show upregulation of EGFR Y1092 phosphorylation (Figures 3b-d).

Figure 3.

N771GY and A767-V769 dup lead to autophosphorylation of YFP-tagged epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) intracellular domain. (a) Schematic model of full-length EGFR and YFP-EGFR-ICD. The amino acid numbering includes the 24 residues of the signal peptide. YFP-EGFR-ICD dose not contain extracellular, transmenbrane and juxtamembrane (JM) domains, but contains tyrosine kinase (TK) and part of the regulatory (Reg) domains. (b) Phosphorylated EGFR Y1092 (red) was detected by antipEGFR Y1092 antibody in the L858R, N771GY, A767-V769dup, but not in S768N and wild-type (wt) YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells. (c) Semi-quantitative comparison of YFP-EGFR-ICD autophosphorylation level using computer-assisted image analysis. Using × 20 object lenses, images of several transfected cells were taken. The fluorescence intensity in the green and the red channels was measured within a cytoplasmic area (YFP signal and AF-594 signal), and within an area outside the cells (background). In the graph, the intensity of the YFP and AF-594 fluorophores for each cell was plotted against each other using Excel (n = 15), and the trend lines were added. At similar expression levels (YFP intensity), the phosphorylated Y1092 level for the N771GY was higher than for the L858R. (d) Quantification of YFP-EGFR-ICD autophosphorylation level by western blotting with indicated antibodies. Densitometorical analysis was performed using ImageJ (Abramoff et al., 2004). DAPI, 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Activation of EGFR downstream signaling pathway in the mutated YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells

Using a specific antibody to detect phosphorylated Akt (pAkt S473), we analyzed the status of EGFR downstream signal in the mutated YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells (Figure 4a). We could not detect pAkt signal in the mock-transfected, wt YFP-EGFR-ICD and S768N-transfected cells. In contrast, we detected pAkt signals in the L858R-, N771GY- and A767-V769dup-transfected MCF7 cells. The pAkt fluorescence was discernable in membrane ruffles. The N771GY and the A767-V769 dup mutants showed higher levels of Akt phosphorylation than the L858R mutant (Figure 4b), suggesting that the N771GY and the A767-V769dup mutations lead to constitutive activation of EGFR downstream signaling.

Figure 4.

The N771GY and A767-V769dup YFP-EGFR-ICD mutants activate downstream signal. (a) Panels show the results of immunofluorescence with pAkt antibodies. Red signals indicating endogenous pAkt expression were detected in the L858R-, N771GY- and A767-V769dup-transfected cells, but not in the wild-type (wt) and the S768N mutant. (b) pAkt level was quantified by western blotting. DAPI, 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; wt, wild type.

Sensitivity of EGFR mutants to erlotinib and PF00299804

We evaluated the response to the reversible EGFR-TKI erlotinib in YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells. After 4 h of transfection, erlotinib was added to the culture medium at final concentrations ranging from 30 to 3 μM. Cells were incubated with the drug for 20 h, and then analyzed under fluorescent microscope. As shown in Figure 5a, there was no effect of erlotinib up to 3 μM in the wt YFP-EGFR-ICD and the L858R/T790M-transfected cells. In contrast, 30 nM erlotinib induced relocation and fibril-like formation of L858R YFP-EGFR-ICD fusion protein in transfected cells. As we reported previously, this fibril-like formations paralleled the sensitivity to erlotinib (de Gunst et al., 2007), and correlated with decreasing downstream pAkt signal (Figure 6). Erlotinib up to 1 pM showed no effect in the N771GY YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells. Erlotinib at 3 μM showed partial effect, as manifested by the appearance of fibril-like formation in only some of the N771GY YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells. These results indicate that the N771GY mutant was more sensitive to erlotinib than wt, but much more resistant than the L858R mutant. The A767-V769dup mutant showed resistance to erlotinib up to 1 pM. At 3 pM of erlotinib, the A767-V769dup mutant exhibited fibril-like formation and decreasing pAkt in most of the transfected cells. In contrast, the S768N YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells showed no response to erlotinb up to 3 μM. We then evaluated the efficacy of PF00299804, which is an irreversible EGFR inhibitor and reported as more potent than erlotinib (Engelman et al., 2007). We showed fibril-like formation in the L858R mutant at 1 nM, N771GY at 50 nM and A767-V769dup at 10 nM of PF00299804 (Figure 5b). Moreover, the fibril-like formation correlated with decreasing pAkt (Figure 6). However, the L858R/T790M double mutant and the S768N mutant were resistant to PF00299804 up to 1000 nM (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Evaluation of sensitivity to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs). YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells were treated with EGFR-TKIs at indicated concentrations for 20 h, and then live cells were subjected to image analysis under a Nikon microscope T-DH. (a) Sensitivities to erlotinib. The L858R YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells showed YFP signal relocation with 30 nM of erlotinib treatment. At 3 μM, erlotinib showed partial effect to the N771GY and the A767-V769V dup YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells. The wild-type, the L858R/T790M and S768N YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells showed no fibril-like formation of YFP signal. (b) Sensitivities to PF00299804. The L858R/T790M and S768N YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells showed no fibril-like formation of YFP signal up to 100 nM. The L858R YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells showed fibril-like formation with 1 nM. A767-V769 dup and N771GY YFP-EGFR-ICD-transfected cells showed fibril-like formation at 10 and 50 nM of PF00299804, respectively.

Figure 6.

Reduction of pAkt concomitant with fibril-like formation of N771GY YFP-EGFR-ICD protein. The drug-treated cells were fixed and immunofluorescence analysis with pAkt antibody was performed. The N771GY YFP-EGFR-ICD cells treated with 3000 nM of erlotinib and 100 nM of PF00299804 showed fibril-like formation, but not pAkt. DAPI, 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Location of the N771GY mutation

Superimposition of N771GY and 767-769dup to the resolved EGFR crystal structure indicates that N771GY and 767-779dup are adjacent to and at the C′-terminal of the c-helix, respectively (Figure 7). The well-known EGFR exon 19 deletions are located in another side of the c-helix. As c-helix has critical role for catalytic activity of EGFR tyrosine kinase (Niculescu-Duvaz et al., 2007; Yun et al., 2007), the exon 20 insertions might push the c-helix and affect the conformation of the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain.

Figure 7.

Comparison of inactive and active conformation of the epidermal growth factor receptor kinase domain. Inactive form (left panel) and active form (right panel; adopted from RSCB protein databank PDBID: 2GS7 and 2GS6, Zhang et al., 2006). The position of the N lobe, the C lobe, the catalytic cleft and the mutations are indicated. The c-helix regions are highlighted in blue. The two forms of kinases are aligned with each other such that their C lobes are in the same relative orientation. The crystal structures reveal the N771 and A767-V779dup are adjacent to and at the C′-terminal of c-helix, respectively. The well-known exon 19 deletion mutation is located another side of c-helix. Residues of known T790M mutation are also indicated.

Discussion

The presence of common EGFR activating mutations (exon 19 deletions and L858R) is highly predictive of response to EGFR-TKIs in patients with advanced NSCLC (Mok et al., 2009). These mutations have been found to be highly prevalent in patients with adenocarcinoma histology, never-smokers, women and East-Asians. Numerous studies have shown significant racial/ ethnic differences in the prevalence of these mutations, which are found in 30–40% of East-Asian patients with NSCLC (Han et al., 2005; Mitsudomi et al., 2005) but in only 10–15% of White/Caucasian patients (Pao et al., 2004; Calvo and Baselga, 2006). Interestingly, there is limited information available about EGFR mutations in African-American patients. To our knowledge, only three studies have included a significant number of patients of African-American descent and out of a total of 155 patients analyzed, only four EGFR mutations (2.6%), including two exon 19 deletions and two exon 20 mutations (S768N and S768I) have been described. (Yang et al., 2005; Krishnaswamy et al., 2009; Leidner et al., 2009). These findings have led to the conclusion that EGFR mutations have an extremely low prevalence in the African-American population (Leidner et al., 2009). However, the vast majority of the patients analyzed (>80%) had a history of smoking and no subset analysis in never- or light-smokers has been performed.

In this study, we described the case of an African-American patient with NSCLC harboring a rare EGFR exon 20 mutation (N771GY), which to our knowledge has not been previously described. Additionally, we found a total of five EGFR activating mutations out of eight never- or light-smokers with NSCLC of African-American descent, but no EGFR mutations were found in heavy smokers. Even though our analysis was conducted at a specialized national referral center and is not powered to make any definitive conclusions about the frequency of EGFR mutations in African Americans, our results suggest that the frequency of these mutations in never smokers may be much higher than reported so far. Furthermore, these results show the importance of patient stratification based on smoking status when conducting molecular studies in patients with NSCLC.

To further understand the functional characteristics and sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs of the exon 20 mutations found in African Americans, we used the YFP-EGFR-ICD assay. This method has been previously described as a useful tool to perform a relatively rapid functional assay for evaluating novel EGFR mutants and the sensitivity to TKIs (de Gunst et al., 2007). In this assay, we judged the sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs by YFP-EGFR relocation, not by cell viability. In terms of cell killing effects of EGFR-TKIs, the sensitivity is dependent on the host cell addiction to EGFR signaling (Chen et al., 2006). Our results suggest that the novel N771GY mutation activates the EGFR tyrosine kinase and appears to be resistant to erlotinib in vitro, showing no effect up to 1 μM of erlotinib treatment, and only few cells showing sensitivity at 3 μM (Figure 5). Taking into consideration that the maximum plasma concentration of erlotinib after oral administration of 150 mg daily is 1.81 μM with a trough concentration of 0.324 μM (mean value, n = 15; Hughes et al., 2009), we conclude that the N771GY mutation should be considered as resistant to reversible EGFR-TKIs in the clinical setting. Furthermore, our laboratory findings were consistent with the clinical outcome of this patient, who in fact progressed rapidly after erlotinib treatment. On the other hand, our experiments with the use of the second generation EGFR-TKI (PF00299804) revealed a different sensitivity profile. PF00299804 is an irreversible pan-ERBB inhibitor, which is considered to be more potent than gefitinib or erlotinib against the T790M resistant mutation in vitro (Engelman et al., 2007). However, limited clinical activity has been shown so far in patients with resistance to EGFR-TKIs (Wong, 2007; Eskens et al., 2008; Sos et al., 2010). Our results showed that PF00299804 was active on N771GY YFP-EGFR-ICD at 50 nM even though it showed no effect on the T790M YFP-EGFR-ICD up to 1 μM, suggesting that the erlotinib-resistant N771GY mutant is sensitive to PF00299804. In addition, we evaluated the S768N point mutation and the A767-V769 dup, which had been previously reported but not functionally characterized (Leidner et al., 2009; Shigematsu et al., 2005). Our results indicate that the A767-V769 dup, but not the S768N, mutation activates the EGFR tyrosine kinase. Both mutations are resistant to erlotinib, but the A767-V769dup was sensitive to PF00299804 at 10 nM, whereas the S768N was resistant at 100 nM. Recently, Wu et al. (2008) reported 9 out of 10 patients, who had exon 20 insertion/duplication mutations and treated with gefitinib, showed progressive disease). The report supports the results obtained with our assay.

It is interesting to note that even though the three EGFR exon 20 mutations (A767-V769dup, N771GY and S768N) found in African-American patients, are very close to each other in relation to the EGFR c-helix (Figure 7), they showed differential EGFR activation patterns and sensitivity to PF00299804. Overall, our results indicate that both A767-V769dup and N771GY are EGFR-activating mutations, resistant to erlotinib clinically and in vitro, and sensitive to the irreversible pan-ERBB inhibitor PF00299804 in vitro. Furthermore, in a recent phase I clinical trial of PF00299804 in patients with NSCLC, there was a partial response in a patient with an EGFR exon 20 mutation D770delinsGY (J O’Connel, Pfizer, personal communication), which is close in proximity to the EGFR c-helix and to the mutations described in this study.

In conclusion, we found a novel exon 20 mutation and a high frequency of EGFR mutations in never-smoking African-American patients. Additionally, we functionally characterized three rare exon 20 mutations found in African Americans and assessed differential sensitivities to erlotinib and a novel irreversible EGFR inhibitor, using a rapid in vitro assay. This assay predicted lack of sensitivity to erlotinib for all three mutations studied and sensitivity to the irreversible inhibitor PF00299804 for A767-V769dup and N771GY. Further studies to functionally characterize and determine the frequency of EGFR mutations and other molecular abnormalities in African-American patients with NSCLC are warranted.

Materials and methods

Tumor specimen and DNA sequencing

Tumor specimens were obtained through protocols approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Institute. DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues using DNeasey tissue and blood kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Exons 18–21 of EGFR tyrosine kinase domain and exons 1–2 of KRAS were sequenced by PCR-direct sequencing. Information of primers is available on request. Sequencing data was analyzed with Mutation Surveyer (Softgenetics, State College, PA, USA).

Plasmid construction and site directed mutagenesis

The wt, L858R and L858R/T790M mutant YFP-EGFR-ICD constructs were generated as described previously (de Gunst et al., 2007). To construct EGFR mutants, QuikChange II sitedirected mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol with the YFP-EGFR-ICD wt as a template. Primers for N771GY are 5′-GGCCAGCGTGGACGGGTACCCCCACGTGTGC-3′ and 5′-GCACACGTGGGGGTACCCGTCCACGCTGGCC-3′. Primers for A767-V769dup are 5′-GCCTACGTGATGGCCAGCGTGGCCAGCGTGGACAACCCCCAC-3′. Primers for S768N are 5′-GCCTACGTGATGGCCAACGTGGACAACCCCCAC-3′ and 5′-GTGGGGGTTGTCCACGTTGGCCATCACGTAGGC-3′.

Cell culture, transfection and drug treatment

Human breast cancer cells MCF-7 were grown in Dulbecco’s modied Eagle’s medium, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were seeded onto sterile glass coverslips in 12-well plates, and transfected with 0.3 μg of plasmid DNA using the Effecten transfection reagent (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Erlotinib (LC laboratories Woburn, MA, USA) and PF00299804, which was obtained from Pfizer (New York, NY, USA), were added at the indicated concentrations 4 h after transfection, and the cells were incubated for 20 h before being processed for immunofluorescence analysis. Erlotinib and PF00299804 treatments were always performed in Dulbecco’s modied Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal calf serum.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy analysis

To evaluate EGFR autophosphorylation, a rabbit antipEGFR-Y1068 (no. 3777, diluted 1:100) antibody was used (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Note that the EGFR numbering system used by the manufacturer does not include the 24-residue signal peptide. According to the numbering system used in this report, the antibodies recognize pY1092.

Furthermore, the rabbit anti-pAkt-S473 antibody (no. 9271, diluted 1:100; Cell Signaling Technology) was used to evaluate activation status of EGFR downstream pathways. The immunostaining procedure was as previously described (de Gunst et al., 2007), with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were fixed using 4.0% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min and permealized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Following a blocking step with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h, the primary antibody diluted in blocking solution was applied for 1 h. After washing with PBS, samples were incubated with AlexaFluor 594 (AF-594)-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h. Finally, the coverslips were mounted onto microscopic slides with Vectashield no. H1200 (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Slides were examined using a Nikon microscope Ecrips 80i (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The software NIS-Elements ver01.01 (Nikon) was used to collect images, keeping exposure time constant to allow for comparison of signal intensity between different samples. The same software was used to carry out semi-quantitative image analysis of YFP-EGFR-ICD expression level and pY1092 phosphorylation level.

Western blotting

Cells were starved with serum-free media for 24 h. Then protein lysates were extracted using RIPA buffer (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Protein lysate (30 μg) was used for western blotting. Antibodies for pEGFR (pY1092), EGFR, pAkt, Akt and α-tubulin were purchased from Cell signaling technology. Western blotting was performed as described elsewhere.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Xia Di for providing the computer model, and Dr Eva Szabo for patient information.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

References

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. (2004). Image processing with Image J. Biophoton Int 11: 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo E, Baselga J. (2006). Ethnic differences in response to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol 24: 2158–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YR, Fu YN, Lin CH, Yang ST, Hu SF, Chen YT et al. (2006). Distinctive activation patterns in constitutively active and gefitinibsensitive EGFR mutants. Oncogene 25: 1205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gunst MM, Gallegos-Ruiz MI, Giaccone G, Rodriguez JA. (2007). Functional analysis of cancer-associated EGFR mutants using a cellular assay with YFP-tagged EGFR intracellular domain. Mol Cancer 6: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Gale CM, Lifshits E, Gonzales AJ, Shimamura T et al. (2007). PF00299804, an irreversible pan-ERBB inhibitor, is effective in lung cancer models with EGFR and ERBB2 mutations that are resistant to gefitinib. Cancer Res 67: 11924–11932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskens FA, Mom CH, Planting AS, Gietema JA, Amelsberg A, Huisman H et al. (2008). A phase I dose escalation study of BIBW 2992, an irreversible dual inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (EGFR) and 2 (HER2) tyrosine kinase in a 2-week on, 2-week off schedule in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br J Cancer 98: 80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SW, Kim TY, Hwang PG, Jeong S, Kim J, Choi IS et al. (2005). Predictive and prognostic impact of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol 23: 2493–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AN, O’Brien ME, Petty WJ, Chick JB, Rankin E, Woll PJ et al. (2009). Overcoming CYP1A1/1A2 mediated induction of metabolism by escalating erlotinib dose in current smokers. J Clin Oncol 27: 1220–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Janne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M et al. (2005). EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 352: 786–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Yoshida K, Hida T, Tsuboi M et al. (2006). Analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and acquired resistance to gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res 12: 5764–5769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaswamy S, Kanteti R, Duke-Cohan JS, Loganathan S, Liu W, Ma PC et al. (2009). Ethnic differences and functional analysis of MET mutations in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 15: 5714–5723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidner RS, Fu P, Clifford B, Hamdan A, Jin C, Eisenberg R et al. (2009). Genetic abnormalities of the EGFR pathway in African American patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 27: 5620–5626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsudomi T, Kosaka T, Endoh H, Horio Y, Hida T, Mori S et al. (2005). Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene predict prolonged survival after gefitinib treatment in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with postoperative recurrence. J Clin Oncol 23: 2513–2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J et al. (2010). Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 11: 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N et al. (2009). Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 361: 947–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu-Duvaz D, Whittaker S, Springer C, Marais R. (2007). The EGF receptor Hokey-Cokey. Cancer Cell 11: 209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I et al. (2004). EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from ‘never smokers’ and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 13306–13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, Porta R, Cardenal F, Camps C et al. (2009). Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med 361: 958–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, Nomura M, Suzuki M, Wistuba II et al. (2005). Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 97: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sos ML, Rode HB, Heynck S, Peifer M, Fischer F, Kluter S et al. (2010). Chemogenomic profiling provides insights into the limited activity of irreversible EGFR Inhibitors in tumor cells expressing the T790 M EGFR resistance mutation. Cancer Res 70: 868–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KK. (2007). HKI-272 in non small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13: s4593–s4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Wu SG, Yang CH, Gow CH, Chang YL, Yu CJ et al. (2008). Lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor exon 20 mutations is associated with poor gefitinib treatment response. Clin Cancer Res 14: 4877–4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SH, Mechanic LE, Yang P, Landi MT, Bowman ED, Wampfler J et al. (2005). Mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11: 2106–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun CH, Boggon TJ, Li Y, Woo MS, Greulich H, Meyerson M et al. (2007). Structures of lung cancer-derived EGFR mutants and inhibitor complexes: mechanism of activation and insights into differential inhibitor sensitivity. Cancer Cell 11: 217–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Gureasko J, Shen K, Cole PA, Kuriyan J. (2006). An allosteric mechanism for activation of the kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cell 125: 1137–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.