Abstract

Objective

To estimate age-specific abortion incidence and unintended pregnancy in Zimbabwe, and to examine differences among adolescents by marital status and residence.

Design

We used a variant of the Abortion Incidence Complications Methodology, an indirect estimation approach, to estimate age-specific abortion incidence. We used three surveys: the Health Facility Survey, a census of 227 facilities that provide postabortion care (PAC); the Health Professional Survey, a purposive sample of key informants knowledgeable about abortion (n=118) and the Prospective Morbidity Survey of PAC patients (n=1002).

Setting

PAC-providing health facilities in Zimbabwe.

Participants

Healthcare providers in PAC-providing facilities and women presenting to facilities with postabortion complications.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was abortion incidence (in rates and ratios). The secondary outcome measure was the proportion of unintended pregnancies that end in abortion.

Results

Adolescent women aged 15–19 years had the lowest abortion rate at five abortions per 1000 women aged 15–19 years compared with other age groups. Adolescents living in urban areas had a higher abortion ratio compared with adolescents in rural areas, and unmarried adolescent women had a higher abortion ratio compared with married adolescents. Unintended pregnancy levels were similar across age groups, and adolescent women had the lowest proportion of unintended pregnancies that ended in induced abortion (9%) compared with other age groups.

Conclusions

This paper provides the first estimates of age-specific abortion and unintended pregnancy in Zimbabwe. Despite similar levels of unintended pregnancy across age groups, these findings suggest that adolescent women have abortions at lower rates and carry a higher proportion of unintended pregnancies to term than older women. Adolescent women are also not a homogeneous group, and youth-focused reproductive health programmes should consider the differences in experiences and barriers to care among young people that affect their ability to decide whether and when to parent.

Keywords: international health services, reproductive medicine, gynaecology

Strengths and limitations of the study.

These are the first estimates of age-specific abortion and unintended pregnancy in Zimbabwe.

The underlying data on the number of postabortion care (PAC) patients come from a census of PAC-providing facilities in Zimbabwe, and the weighted age and subgroup distribution of PAC patients is from a nationally representative sample of PAC-providing facilities.

Using the national multiplier for all age and marital status groups assumes that complication rates and treatment seeking do not differ by age or marital status, which could introduce potential biases in the estimates.

We tested the validity of these assumptions of the national multiplier using PAC patient data, the only available source of representative data on abortion complications and treatment among women in Zimbabwe, and interpreted the results in light of these validity tests.

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period for laying the foundation for positive sexual and reproductive health (SRH), but adolescents worldwide can face various SRH challenges due to sociocultural and political factors that restrict information and services for adolescents.1 2 One of these challenges faced by adolescents is unsafe abortion, particularly in legally restrictive settings, and there is a growing body of literature documenting adolescent abortion experiences in these settings.2–7 These data on adolescents’ experiences with abortion and inequities in care among adolescents fill in information gaps that can inform policies and programmes that intend to prevent unsafe abortion and its consequences among adolescent women.8

In Zimbabwe, abortion is highly restricted and limited to circumstances of saving the woman’s physical health or in cases of rape, incest or foetal impairment per the 1977 Termination of Pregnancy Act.9 Even access to legal abortion under these circumstances is difficult given abortion stigma among both women and providers as well as legal and administrative barriers.10 11 Zimbabwe has one of the lowest abortion rates in Africa estimated at 17 abortions per 1000 women of reproductive age, likely due to high rates of contraceptive use.12 Abortion safety is of particular concern in Zimbabwe given the high levels of maternal mortality (651 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births).13 An estimated 76% of abortions in Eastern Africa (where Zimbabwe is located) are unsafe14 and, among Zimbabwean women experiencing abortion complications, 40% are classified as having moderate to severe complications.15

While adolescents account for 22% of the female population in Zimbabwe, little is known about their experiences with abortion-related care. However, there is information on adolescent-specific challenges accessing other SRH services, such as contraception. Despite Zimbabwe’s strong family planning programme, disparities remain with adolescents aged 15–19 years who want to avoid pregnancy having almost double the unmet need for modern contraception compared with women aged 20–49 years who want to avoid pregnancy.13 To improve adolescent SRH, the Zimbabwean Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) released an updated National Adolescent and Youth Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy in 2016 with goals of increasing availability and affordability of SRH and HIV services for adolescents and creating a policy and legal environment that protects the SRH and rights of adolescents.16 In addition, the MoHCC 2018 family planning guidelines include a specific adolescent focus with a strategic goal of reducing unmet need for contraception among adolescents.17 However, studies have shown that stigma, provider judgement and negative attitudes, and lack of information are persistent barriers for adolescents accessing SRH care in Zimbabwe.18–20 Due to the current disparities in SRH outcomes and barriers to SRH care experienced by adolescents, we hypothesise that the incidence of abortion and unintended pregnancy will differ between adolescents and all women of reproductive age.

Zimbabwean adolescents are a diverse group with varying identities: 20% are currently married and 33% live in urban areas.13 While young women overall might have different experiences seeking abortion-related services compared with older women, there might also be differences among adolescents across these varying identities.5–7 For instance, a study in Uganda found that unmarried postabortion care (PAC) patients, both adolescent and non-adolescent, have higher odds of experiencing severe postabortion complications than non-adolescent married women.5 There is evidence that contraceptive need and use and sexual behaviour, both determinants of unintended pregnancy, vary by marital status and residence among adolescents in Zimbabwe. Among sexually active adolescent women who want to avoid pregnancy, unmarried adolescents have almost double the level of unmet need for modern contraception (39%) compared with married adolescent women (22%).13 A higher proportion of adolescent women living in rural areas have ever had sex (39%) compared with adolescents living in urban areas (21%).13 Adolescents of different marital or residence statuses might also experience varying levels of stigma around accessing abortion-related services in Zimbabwe.20 21 We therefore hypothesise that the incidence of abortion and unintended pregnancy will differ between married and unmarried adolescents, as well as between adolescents living in rural or urban areas. Understanding the intersecting identities of adolescents has important programme and policy implications for reducing unsafe abortions and unintended pregnancy in this age group.5 20

This paper seeks to find out if adolescent women aged 15–19 years have abortions and experience unintended pregnancy at different levels compared with other age groups in Zimbabwe, and also if there are differences among adolescents, particularly looking at the subgroups of marital status (currently married or unmarried) and residence (urban or rural). We explore the following research questions:

What is the incidence of abortion among adolescents compared with other age groups in Zimbabwe?

How does abortion incidence differ by marital status or residence among adolescents and compared with all women of reproductive age?

What proportion of unintended pregnancies among adolescents end in abortion compared with other age groups? Does that differ by subgroups within adolescents, such as by marital status or residence?

This study provides the first age-specific estimates of abortion and unintended pregnancy in Zimbabwe. These findings have the potential to inform policies and programmes aimed at addressing unsafe abortion among adolescents and improving adolescent SRH in Zimbabwe.

Methods

We used an age-specific variant of the Abortion Incidence Complications Methodology (AICM), an indirect estimation approach, to estimate age-specific abortion rates.5 6 The AICM has been used in over 20 countries with restrictive abortion laws to indirectly measure the incidence of abortion.12 22–35 This indirect method obtains the national number of facility-based PAC cases and estimates the proportion of abortions that would result in women having complications and receiving PAC. An age-specific variant of the AICM was employed in Ethiopia and Uganda, and we followed the approach in those studies.5 6

We calculated abortion incidence by age groups (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34 and 35–49). We also calculated abortion incidence by marital status and residence subgroups within two age groups: adolescent women (aged 15–19 years) and all women of reproductive age (15–49 years). We defined the marital status subgroup dichotomously based on PAC patients’ self-report of being currently married/in union or not currently married. We categorised the dichotomous residence subgroup based on PAC patients’ self-report of living in urban or rural areas.

Data

The AICM approach relies on three key data inputs: the number of PAC cases, the proportion of all abortions that result in treated complications, and the age distribution (as well as marital status and place of residence) of PAC patients. These data inputs come from three surveys that were conducted in Zimbabwe in August to November 2016 as part of a larger study that indirectly estimated the incidence of abortion.12 The data on the estimated annual number of PAC cases came from a Health Facility Survey (HFS), which interviewed PAC providers in a census of 227 facilities that provide PAC in Zimbabwe. This was combined with estimates of the proportion of abortions that resulted in complications that received treatment from a Health Professional Survey (HPS), which was a purposive sample of 118 key informants knowledgeable about abortion provision in Zimbabwe. The data on the characteristics of women receiving PAC came from the Prospective Morbidity Survey (PMS), which was conducted in a nationally representative sample of facilities with PAC capacity, using the HFS universe as the sampling frame. Data were collected on all women presenting to the 127 participating facilities for PAC during the 28-day study period (unweighted n=1002). Sociodemographic characteristics of PAC patients from the PMS can be found in online supplementary file 1. The HFS and PMS collected information on women who received PAC in health facilities for either induced abortions or miscarriages. Further details on the study design, sampling and informed consent processes for the HFS and HPS can be found in Sully et al 12 and in Madziyire et al for the PMS.15

bmjopen-2019-034736supp001.pdf (66.8KB, pdf)

We used age-specific fertility rates from the 2015 Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey (ZDHS)13 and age-specific population numbers of women of reproductive age from the Zimbabwe National Statistic Agency’s (ZNSA) Population Projections Report to calculate the age-specific number of births.36

Analysis: AICM

This first step of the age-specific variant of the AICM estimated the number of PAC cases by age group. This was done by multiplying the national number of PAC cases in Zimbabwe12 by the weighted age distribution of PAC patients in the PMS.15 To calculate the number of urban and rural PAC patients within the 15–19 and 15–49 age groups, we multiplied this age-specific number of PAC cases times the proportion of PAC patients within that age group who self-reported living in rural or urban areas. We did the same for PAC patient’s self-reported marital status.

Second, we estimated the age-specific number of PAC cases due to induced abortion. To do this, we first estimated the proportion of second trimester miscarriages by age group6 37 and then adjusted this by the proportion of those miscarriages likely to receive treatment. In the absence of data on access to PAC, we assumed the proportion of women receiving care was equal to the age and subgroup specific proportion of women who give birth in a facility from the ZDHS.13 The result was subtracted from the total number of PAC cases to obtain the number that was due to induced abortion.

The third step was estimating abortions that do not result in facility-based care. This could be due to two reasons: (1) the person having the abortion did not have complications and therefore did not need facility-based treatment or (2) the person having the abortion had complications but did not receive facility-based treatment. In Zimbabwe in 2016, it was estimated that for every one woman receiving PAC, there were 4.7 women who had abortions that did not result in facility-based care (see online supplementary file 2). This estimate, referred to as the multiplier, was applied to all age groups and marital status subgroups in the absence of age-specific and marital status-specific multipliers. We calculated new multipliers for rural women and urban women separately, using the underlying data from the HPS, which was collected separately by residence. Since the HPS is a purposive sample, we could not estimate 95% CI around the multiplier. We therefore conducted a bootstrapping simulation of 10 000 draws with replacement from the HPS respondents and calculated a multiplier with each draw.12 The upper and lower bounds presented contain 95% of the multiplier values from the bootstrapping. Further details on the multiplier calculations are in online supplementary file 2.

bmjopen-2019-034736supp002.pdf (724.3KB, pdf)

Fourth, to estimate the total number of induced abortions by age and subgroup, we multiplied the number of induced abortions that received PAC times the respective multiplier for that age and subgroup. We then adjusted all estimates to account for abortions occurring outside of Zimbabwe, estimated from the HPS as 12% of all abortions, which we assumed was the same across all age and subgroups due to lack of data availability.12 Online supplementary file 2 provides more details on the steps of the AICM, data sources and assumptions, and adjustments made to align all summed age groups and subgroups to national totals.

We calculated age-specific abortion rates per 1000 women by dividing the total number of induced abortions by the age-specific population size, which was taken from the ZNSA Population Projections Report.36 We also wanted to account for risk of pregnancy given the lower levels of reported recent sexual activity, defined as sex in the past 12 months, among adolescents (29%) compared with women aged 20–49 years (84%).13 Therefore, we also calculated separate estimates of age-specific abortion rates among women who reported having sex in the previous 12 months. We estimated age and subgroup specific abortion ratios per 100 live births by dividing the number of induced abortions by the age and subgroup specific number of births.13 36 To calculate the number of births by marital status and residence among 15–19 and 15–49 age groups, we multiplied the age-specific number of births by the age-specific proportion of births to married or unmarried women (or the proportion of births among women who lived in urban or rural areas) from the ZDHS.13 Lastly, we estimated unintended pregnancy by age and subgroup using the age and subgroup specific abortion estimates, age and subgroup specific data on births by intention status from the ZDHS,13 and estimated miscarriages, which were estimated to be 20% of births and 10% of abortions and applied uniformly across age groups.38

Analysis: testing assumptions in the multiplier

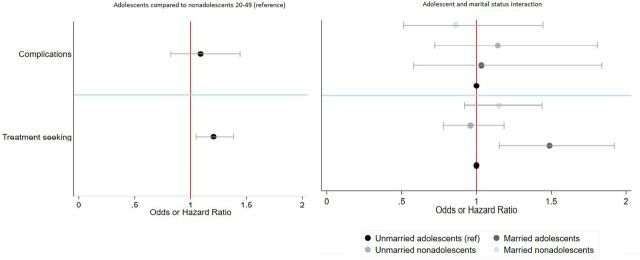

Using the national multiplier for all age and marital status groups assumes that complication rates and treatment seeking do not differ by age or marital status. We tested the validity of these assumptions using PAC patient data, the only available source of representative data on abortion complications and treatment among women in Zimbabwe.

The first assumption we tested was whether experiencing complications differed between adolescent and non-adolescent PAC patients, and if this differed by marital status among adolescents. We operationalised complications using the severity classifications from Madziyire et al 15 and considered moderate and severe complications, maternal near-miss and maternal death as having a complication (coded as 1) and a mild complication (defined as no infection, no organ failure and no blood transfusion needed) as no complication (coded as 0). Using this complication variable as the dependent variable, we ran multivariable logistic regression models comparing adolescents versus non-adolescents, and then included an interaction term between adolescents and marital status.

The second assumption we tested was whether adolescent and non-adolescent PAC patients differed in treatment seeking. PAC patients provided information on their delays in seeking care from the (1) time (in hours) it took from realising they had a complication to deciding to seek treatment and (2) time (in hours) it took from them deciding to seek care to the time they arrived at the facility. These two delays are related to user-related health seeking behaviours (delay 1) as well as access to facilities (delay 2), which when combined capture treatment seeking experiences.39–41 We ran a Cox proportional hazards model to estimate differences in hazard ratios between adolescents and non-adolescents, and we included an interaction term between adolescents and marital status. All models controlled for residence, secondary education, wealth, previous pregnancy, whether the pregnancy was reported as unintended and being in the second trimester.

Patient and public involvement

This research involved interviews with postabortion care patients. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design or involved in the writing or editing of this document. We sought guidance for study planning and dissemination from our Technical Advisory Committee, which included community representatives and technical experts.

Results

Abortion incidence

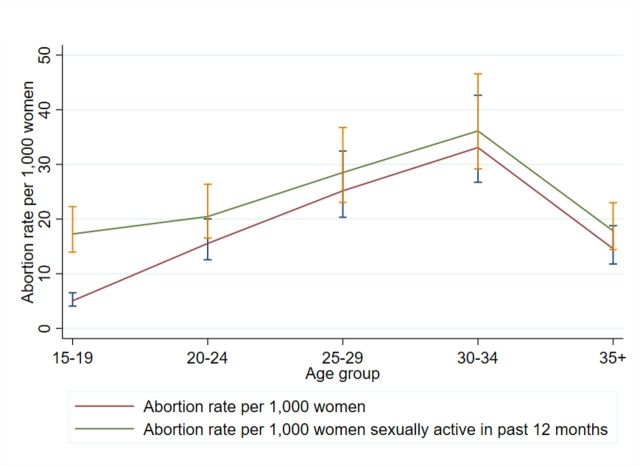

In 2016, approximately 4155 induced abortions occurred among adolescent women in Zimbabwe. Adolescent women aged 15–19 years had the lowest abortion rate compared with other age groups at five induced abortions per 1000 women aged 15–19 years (Uncertainty Interval (UI): 4.1, 6.5) (figure 1). Women aged 30–34 years had the highest abortion rate of 33 per 1000 women aged 30–34 years (UI: 26.7, 42.6). Among women who reported sexual activity in the past 12 months, the abortion rate for adolescents increased to 17.3 per 1000 women aged 15–19 years (UI: 13.9, 22.3), but remained the lowest abortion rate among all age groups (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age-specific induced abortion rates, Zimbabwe 2016.

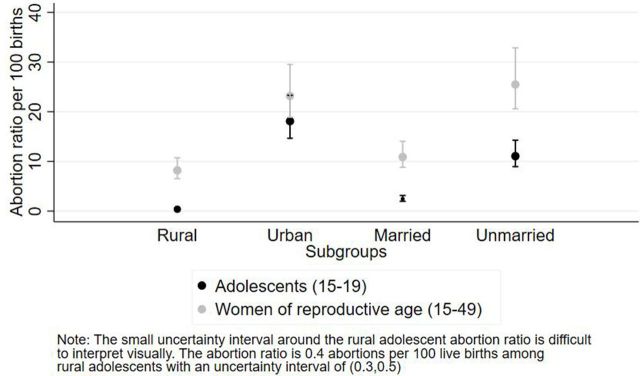

An abortion ratio indicates the likelihood of a pregnancy ending in an abortion rather than a live birth. Adolescent women had a lower abortion ratio compared with all women of reproductive age (15–49 years) in all residence and marital status subgroups (figure 2). Adolescent women living in urban areas had a higher abortion ratio of 18.1 abortions per 100 live births (UI: 14.6, 23.3) compared with adolescents living in rural areas (0.4 abortions per 100 live births (UI: 0.3, 0.5), and this urban/rural difference remained true for all women of reproductive age (figure 2). Unmarried adolescent women had an abortion ratio of 11.1 per 100 live births (UI: 8.9, 14.3) compared with 2.4 per 100 live births among married adolescents (UI: 2.0, 3.1). This marital status difference remained consistent among all women of reproductive age, where unmarried women aged 15–49 years had an abortion ratio of 25.5 per 100 live births (UI: 20.6, 32.8) compared with 10.9 per 100 live births among married women aged 15–49 years (UI: 8.8, 14.0) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Abortion ratio among adolescent women (15–19 years) and all women of reproductive age (15–49 years), by subgroups, Zimbabwe 2016.

Unintended pregnancy

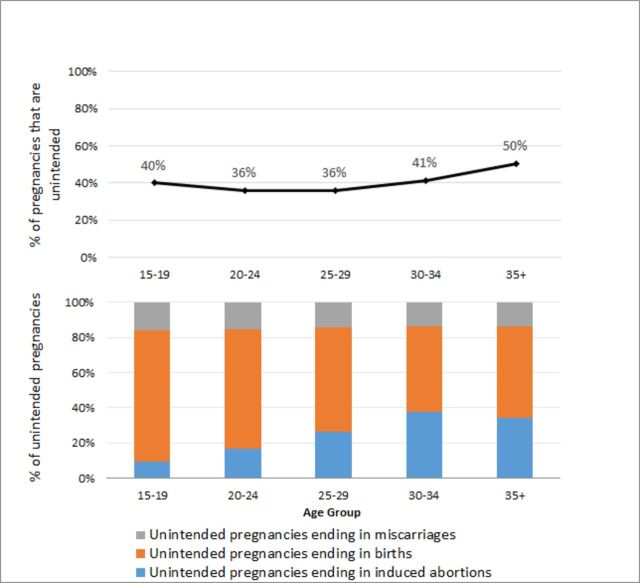

There were an estimated 45 387 unintended pregnancies among adolescent women, which was 17% of the estimated total 267 497 unintended pregnancies in Zimbabwe in 2016 (data not shown). Adolescent women had the lowest percent of unintended pregnancies that ended in induced abortion (9%) compared with all other age groups (ranging from 17% among 20–24 year olds to 38% among 30–34 year olds) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Age-specific proportion of pregnancies that are unintended and unintended pregnancy outcome distribution, Zimbabwe 2016.

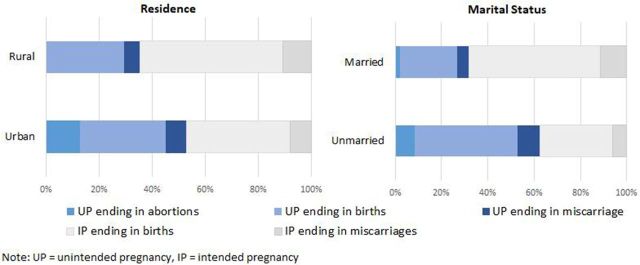

Unmarried adolescents had almost double the proportion of pregnancies that were unintended (63%) compared with married adolescents (32%) (figure 4). Just over half of pregnancies (53%) were unintended among urban adolescent women compared with 35% among rural adolescents (figure 4). One-quarter (25%) of unintended pregnancies among adolescents living in urban areas ended in abortion compared with 1% among adolescents living in rural areas (figure 4). Thirteen per cent of unintended pregnancies among unmarried adolescents ended in abortion, compared with just 6% among married adolescents (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Pregnancy outcome distribution among subgroups of adolescents, Zimbabwe 2016.

Complications and delays to care among PAC patients by age and marital status

We found that adolescent and non-adolescent PAC patients did not significantly differ in their likelihood of experiencing complications (OR: 1.1, 95% CI: 0.82, 1.44) and married versus unmarried adolescents also did not differ (OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.58, 1.84) (figure 5). Adolescent PAC patients are 21% more likely to experience delays in seeking care compared with non-adolescents (HR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.39). Married adolescent PAC patients are 45% more likely to experience delays in seeking care compared with unmarried adolescents (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.15, 1.92) (figure 5). We conducted a sensitivity test for outliers in delays by capping the delays at 2 weeks (since a longer duration than 2 weeks might be due to reporting errors or recall bias) and the results did not vary.

Figure 5.

Likelihood of complications and delays in treatment seeking between adolescents and non-adolescents, and by marital status, Zimbabwe 2016.

Discussion

This paper provides the first estimates of age-specific abortion and unintended pregnancy in Zimbabwe. Adolescent women are estimated to have the lowest abortion rate of all age groups in Zimbabwe, and while the overall level of unintended pregnancy does not differ greatly by age group, adolescent women had the lowest proportion of unintended pregnancies that ended in induced abortion (9%) compared with other age groups. Studies in Ethiopia and Uganda found that adolescent women had the lowest abortion rate when compared with women less than 35 years old, but when accounting for recent sexual activity and therefore risk of pregnancy, these studies found that adolescents had the highest abortion rate.5 6 Despite accounting for recent sexual activity, adolescent women in Zimbabwe still obtain abortions at lower rates compared with all other age groups. Together, these findings suggest that despite similar levels of unintended pregnancy across age groups, adolescent women have abortions at lower rates and carry a higher proportion of unintended pregnancies to term. Unwanted childbearing can have social and economic impacts on young women and their children, such as lower rates of school completion and limited future economic opportunities.42 43

We also found that adolescents obtain abortions at different rates across marital status and place of residence. We found that unmarried adolescents or adolescents living in urban areas have a higher abortion ratio compared with their married or rural counterparts, respectively. A qualitative study found that Zimbabwean women cited unstable partner relationships and a desire to hide extramarital pregnancies as reasons why they sought an abortion, which could explain the higher abortion ratio we see among unmarried adolescent women.10 The social stigma around extramarital sex and pregnancy is high in Zimbabwe, and is likely a strong factor in influencing unmarried adolescent women to terminate their pregnancy. Regarding differences by place of residence, a study among South African adolescents found that adolescents living in urban areas had more knowledge and favourable attitudes towards abortions compared with their rural counterparts, which could help explain the higher abortion incidence among adolescents living in urban areas.44 However, more research is needed to understand the factors that influence Zimbabwean adolescents to seek an abortion or continue with the pregnancy, which can also inform how adolescents can be better supported in pregnancy.45

We also found that adolescents were more likely to experience delays in seeking care for abortion complications compared with non-adolescent PAC patients and married adolescent PAC patients experienced longer delays than their unmarried counterparts. Along with the lower abortion rate among adolescents compared with other age groups even when adjusting for recent sexual activity, these findings suggest that the barriers adolescents face when trying to prevent unintended pregnancies, such as stigma, provider bias or lack of information, might also limit their ability to terminate unintended pregnancies or seek care for abortion-related complications.18–20 46 47 Cost might also be a barrier since adolescents may have less access to financial resources needed to obtain an abortion or treatment for abortion complications, especially given the sustained economic crisis and cash shortages in Zimbabwe.46 48 49 Other studies have found that the cost of obtaining PAC can be catastrophic to women and their families,50 so a lack of control over household resources, such as by married adolescents,49 may contribute to the longer delays to care experienced by married PAC patients. Macroeconomic conditions could also affect access to and quality of care, and the decades of economic decline and resource constraints in Zimbabwe are important to consider in future research.

There are some potential sources of underestimation of adolescent abortions due to limitations in the data. First, if adolescents are more likely to obtain medical abortions (that would not result in complications), then that would not be captured in the national multiplier, and we could therefore be underestimating the number of adolescent abortions. Second, since the multiplier estimates how many women with induced abortions do not present to health facilities for every one woman who does, and because adolescent PAC patients are more likely to experience delays in seeking PAC, it is possible that the national multiplier for adolescents is an underestimate, which would result in underestimating adolescent abortions. In addition, if the same factors that determine delays for adolescents also determine not seeking care at all, then that might be another potential source of underestimation. However, it is possible that treatment seeking differs between PAC patients and all women who had abortions, limiting our ability to infer potential bias in our estimates from data on PAC patients alone. Third, our assumption that there is no difference in abortions sought in neighbouring countries by age might underestimate adolescent abortions if adolescents are more likely to travel for abortion. In addition, this assumption could also underestimate the number of abortions occurring among adolescents living in rural areas since more rural areas share direct borders with neighbouring countries with more liberalised abortion laws (eg, South Africa).

The age distribution of all women obtaining abortions in Zimbabwe differs slightly from other African countries with comparable data. While adolescents similarly do not disproportionally obtain abortions in the Congo Republic, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana and Uganda, women aged 20–29 years in these countries had the highest abortion rates,3 5 whereas the highest abortion rate in Zimbabwe is among 30–34 year olds. Zimbabwean women aged 30–34 years primarily use contraception as a means to limit fertility compared with younger women,13 which suggests that abortion may be used by women in this age group to limit fertility rather than space or delay births in order to maintain desired family size. However, further research is needed to determine why the abortion rate trend peaks at later ages in Zimbabwe.

These findings highlight some important policy recommendations. First, given the high levels of unintended pregnancy among adolescents, particularly unmarried adolescents or adolescents living in urban areas, policies and programmes should target the different needs of adolescents across subgroups in order to ensure equitable access to contraceptive counselling and services. For example, an evaluation of the implementation of the National Adolescent SRH Strategy between 2010 and 2015 encouraged differentiating service delivery based on the social context of adolescents.51 Therefore, the updated national strategy and subsequent policies should have explicit strategies that ensure access to quality SRH care to diverse groups of adolescents, with a particular focus on those who are most disadvantaged. Second, multi-sectoral policies should focus on breaking down the stigma of adolescent sexual activity and use of SRH services through various avenues, including closing communication gaps with parents, ensuring the provision of comprehensive sexuality education and conducting healthcare provider trainings on respectful, non-discriminatory and stigma-free reproductive healthcare.18–20 47 If the factors preventing adolescents to avoid unintended pregnancy also limit their ability to terminate a pregnancy, then addressing these factors could reduce unintended pregnancy and unwanted childbearing among adolescents.

This study has some important limitations. First, there are potential issues of reliability in subgroup calculations. We are using nationally representative data on PAC patients to distribute cases into subgroups, but since the PAC sample size is 1002 women,15 breaking the data down into subgroups reduces the reliability of the data. Second, since married adolescents are more likely to report their births as planned due to social expectations,1 the proportion of married adolescents reporting unplanned births is likely a conservative estimate and therefore the estimate of married adolescent unintended pregnancy could be an underestimate. Third, the estimated proportion of abortions occurring outside of Zimbabwe is not age specific, and this also likely varies by age. Fourth, in examining characteristics and treatment seeking behaviours among PAC patients, we cannot distinguish between women having an induced abortion or miscarriage and treatment seeking behaviours may be different among women seeking treatment for an induced abortion compared with a miscarriage.

Conclusion

This paper provides important information on the age-specific incidence of abortion and unintended pregnancy. Adolescents obtain abortions at lower rates compared with other age groups, even when accounting for recent sexual activity, but have similar levels of unintended pregnancy and carry a higher proportion of unintended pregnancies to term compared with non-adolescents. This unwanted childbearing can have social, economic and health impacts on young women that can influence their life trajectories.1 Adolescents need increased access to comprehensive and voluntary contraceptive information and services, as well as information about accessing safe abortion services when possible, given the limited legal conditions available. Adolescent women are also not a homogeneous group, and youth-focused reproductive health policies and programmes should consider the differences in experiences and barriers to care among young people that affect their ability to decide whether and when to parent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Florby Dorme and Meg Schurr of the Guttmacher Institute for research assistance and project management, and Adesegun Fatusi of the Guttmacher Institute for his feedback. We also acknowledge the data collectors and fieldwork team who worked to gather this data, and the respondents that gave their time in the interviews.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Mugogynae

Contributors: TR helped in conception of the study, performed the analysis, interpreted the results and led the writing of the manuscript. MGM participated in the acquisition of data, interpreted the results and was a contributor in writing and reviewing the manuscript. TC participated in the acquisition of data, interpreted the results and reviewed and commented on the manuscript. ES led the conception of the study, participated in the acquisition of data, interpreted the results and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors have read the final manuscript and agreed to its publication.

Funding: This study was made possible by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and UK Aid from the UK Government. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions and policies of the donors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: We obtained ethical approval from the institutional ethics board of the Guttmacher Institute (20 May 2016), the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (28 April 2016, approval number MRCZ/A/2061) and from the Joint Research Ethics Committee for the University of Zimbabwe, College of Health Sciences and Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals (4 April 2016, reference number JREC/379/15).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The data collected by the authors and used in this study are publicly available and have been de-identified. The Health Facilities Survey can be accessed under DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.5778021, and the Health Professionals can be accessed under DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.5778024. Given the sensitive nature of the PMS data, the dataset is not currently publically available. We are determining ethical clearance to make this data set available to other researchers. The Zimbabwe 2015 Demographic and Health Survey Births and Individual data files are available here: https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Zimbabwe_Standard-DHS_2015.cfm.

References

- 1. Woog V, Singh S, Browne A, et al. Adolescent Women’s Need for and Use of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Developing Countries. Guttmacher Institute, 2015. Available: www.guttmacher.org/pubs/AdolescentSRHS-Need-Developing-Countries.pdf

- 2. Morris JL, Rushwan H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: the global challenges. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131 Suppl 1:S40–2. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chae S, Desai S, Crowell M, et al. Characteristics of women obtaining induced abortions in selected low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One 2017;12:e0172976. 10.1371/journal.pone.0172976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levandowski BA, Pearson E, Lunguzi J, et al. Reproductive health characteristics of young Malawian women seeking post-abortion care. Afr J Reprod Health 2012;16:253–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sully EA, Atuyambe L, Bukenya J, et al. Estimating abortion incidence among adolescents and differences in postabortion care by age: a cross-sectional study of postabortion care patients in Uganda. Contraception 2018;98:510–6. 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.07.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sully E, Dibaba Y, Fetters T, et al. Playing it safe: legal and clandestine abortions among adolescents in Ethiopia. J Adolesc Health 2018;62:729–36. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mutua MM, Maina BW, Achia TO, et al. Factors associated with delays in seeking post abortion care among women in Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:241. 10.1186/s12884-015-0660-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Every Woman Every Child. The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health 2016-2030, 2015. Available: http://www.everywomaneverychild.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/EWEC_GSUpdate_Full_EN_2017_web-1.pdf

- 9. Zimbabwe Termination of Pregnancy Act [Chapter 15:10], 1977. Available: http://www.parlzim.gov.zw/acts-list/termination-of-pregnancy-act-15-10

- 10. Chiweshe M, Mavuso J, Macleod C. Reproductive justice in context: South African and Zimbabwean women’s narratives of their abortion decision. Fem Psychol 2017;27:203–24. 10.1177/0959353517699234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maternowska MC, Mashu A, Moyo P, et al. Perceptions of misoprostol among providers and women seeking post-abortion care in Zimbabwe. Reprod Health Matters 2015;22:16–25. 10.1016/S0968-8080(14)43792-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sully EA, Madziyire MG, Riley T, et al. Abortion in Zimbabwe: a national study of the incidence of induced abortion, unintended pregnancy and post-abortion care in 2016. PLoS One 2018;13:e0205239. 10.1371/journal.pone.0205239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, ICF International Zimbabwe demographic and health survey 2015: final report, 2016. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr322-dhs-final-reports.cfm [Accessed 13 Feb 2019].

- 14. Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. The Lancet 2017;390:2372–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Madziyire MG, Polis CB, Riley T, et al. Severity and management of postabortion complications among women in Zimbabwe, 2016: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019658. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. GoZ National adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) strategy II 2016-2020: stepping up for good sexual and reproductive health outcomes for adolescents and youth in Zimbabwe. Harare: Goverment of Zimbabwe, Ministry of health and child care, 2016. Available: http://www.znfpc.org.zw/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/National-ASRH-Strategy-II-2016-2020.pdf [Accessed Sep 2019].

- 17. Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC), UNFPA, UNFPA Family planning guidelines for Zimbabwe. UNFPA, 2019. Available: https://zimbabwe.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Family%20Planning%20Guidelines%20for%20Zimbabwe.pdf [Accessed 19 Sep 2019].

- 18. Kurebwa J. Knowledge and perceptions of adolescent sexual and reproductive health issues among rural adolescence in Gutu rural district of Zimbabwe. Int J Adv Res Publ 2017;1:8. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Langhaug LF, Cowan FM, Nyamurera T, et al. Improving young people's access to reproductive health care in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 2003;15:147–57. 10.1080/0954012031000068290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mashamba A, Robson E. Youth reproductive health services in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Health Place 2002;8:273–83. 10.1016/S1353-8292(02)00007-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wekwete N, Rusakaniko S, Zimbizi G. UNFPA Zimbabwe national adolescent fertility study. Harare: Ministry of Health and Child Care, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Polis CB, Mhango C, Philbin J, et al. Incidence of induced abortion in Malawi, 2015. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173639. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Keogh SC, Kimaro G, Muganyizi P, et al. Incidence of induced abortion and post-abortion care in Tanzania. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133933. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Basinga P, Moore AM, Singh SD, et al. Abortion incidence and postabortion care in Rwanda. Stud Fam Plann 2012;43:11–20. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00298.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mohamed SF, Izugbara C, Moore AM, et al. The estimated incidence of induced abortion in Kenya: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:185. 10.1186/s12884-015-0621-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Singh S, Prada E, Juarez F. The Abortion Incidence Complications Method: A Quantitative Technique : Singh S, Remez L, Tartaglione A, Methodologies for Estimating Abortion Incidence and Abortion-Related Morbidity: A Review. New York and Paris: Guttmacher Institute and International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, 2010: 63––70. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bankole A, Adewole IF, Hussain R, et al. The incidence of abortion in Nigeria. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2015;41:170–81. 10.1363/intsexrephea.41.4.0170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh S, Prada E, Mirembe F, et al. The incidence of induced abortion in Uganda. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2005;31:183–91. 10.1363/3118305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prada E, Atuyambe LM, Blades NM, et al. Incidence of induced abortion in Uganda, 2013: new estimates since 2003. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165812. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levandowski BA, Mhango C, Kuchingale E, et al. The incidence of induced abortion in Malawi. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2013;39:088–96. 10.1363/3908813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Singh S, Fetters T, Gebreselassie H, et al. The estimated incidence of induced abortion in Ethiopia, 2008. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2010;36:016–25. 10.1363/3601610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sedgh G, Rossier C, Kaboré I, et al. Estimating abortion incidence in Burkina Faso using two methodologies. Stud Fam Plann 2011;42:147–54. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sedgh G, Sylla AH, Philbin J, et al. Estimates of the incidence of induced abortion and consequences of unsafe abortion in Senegal. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2015;41:11–19. 10.1363/4101115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chae S, Kayembe PK, Philbin J, et al. The incidence of induced abortion in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2016. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184389. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moore AM, Gebrehiwot Y, Fetters T, et al. The estimated incidence of induced abortion in Ethiopia, 2014: changes in the provision of services since 2008. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2016;42:111–20. 10.1363/42e1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT), UNFPA Population projections thematic report. Harare: ZIMSTAT, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harlap S, Shiono P, Ramcharan S. Human embryonic and fetal death : Porter I, Hook E, A life table of spontaneous abortions and the effects of age, parity and other variables. New York: Academic Press, 1980: 145–58. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leridon H. Human Fertility: The Basic Component. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1091–110. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mgawadere F, Unkels R, Kazembe A, et al. Factors associated with maternal mortality in Malawi: application of the three delays model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:219. 10.1186/s12884-017-1406-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pacagnella RC, Cecatti JG, Parpinelli MA, et al. Delays in receiving obstetric care and poor maternal outcomes: results from a national multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:159. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. UNESCO Developing an education sector response to early and unintended pregnancy. Paris: United nations educational, scientific, and cultural organization, 2014. Available: http://www.ungei.org/resources/files/Developing_an_education_sector_response_to_early_and_unintended_pregnancy_Global_consultation_4-6_Nov_2014.pdf [Accessed 16 Jul 2019].

- 43. Fall CHD, Sachdev HS, Osmond C, et al. Association between maternal age at childbirth and child and adult outcomes in the offspring: a prospective study in five low-income and middle-income countries (cohorts collaboration). Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e366–77. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00038-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Varga CA. Pregnancy termination among South African adolescents. Stud Fam Plann 2002;33:283–98. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sedgh G, Finer LB, Bankole A, et al. Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trends. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:223–30. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Olukoya AA, Kaya A, Ferguson BJ, et al. Unsafe abortion in adolescents. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001;75:137–47. 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00370-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Landa NM, Fushai K. Exploring discourses of sexual and reproductive health taboos/silences among youth in Zimbabwe. Cogent Med 2018;5:1501188 10.1080/2331205X.2018.1501188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bank W. Macro poverty outlook for Zimbabwe. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2016. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/378671475867933282/Macro-poverty-outlook-for-Zimbabwe [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ganatra B, Hirve S. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra, India. Reprod Health Matters 2002;10:76–85. 10.1016/S0968-8080(02)00016-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ilboudo PGC, Greco G, Sundby J, et al. Costs and consequences of abortions to women and their households: a cross-sectional study in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:500–7. 10.1093/heapol/czu025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Muchabaiwa L, Mbonigaba J. Impact of the adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health strategy on service utilisation and health outcomes in Zimbabwe. PLoS One 2019;14:e0218588. 10.1371/journal.pone.0218588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034736supp001.pdf (66.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-034736supp002.pdf (724.3KB, pdf)