Abstract

Introduction

Mental health services are an area of high need in many health care systems in the United States. With a limited number of psychiatric providers and a projected increase in the deficit of psychiatrists, a call for increased mental health services is apparent. The inclusion of mental health clinical pharmacy specialists (MH-CPS) as part of interdisciplinary care teams has enabled the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital & Clinics as well as numerous other Veterans Affairs sites to improve access to mental health providers when pharmacists serve as an integral part of the mental health team. Our objectives were to (1) evaluate impressions of nonpharmacist mental health providers of MH-CPS and (2) assess for areas of improvement in MH-CPS services.

Methods

A survey was formulated, using 5-point Likert scale criteria, to evaluate impressions of MH-CPS from other mental health providers. Questions were designed to address impressions of clinical skills, knowledge, team contribution, and comfort with MH-CPS providers. These were distributed and completed in December 2018 by members of mental health treatment teams at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital & Clinics.

Results

Overall, mental health team members rated satisfaction with MH-CPS highly across all evaluated criteria.

Discussion

Per review of these results, MH-CPS are a valued and respected part of the mental health team.

Keywords: clinical pharmacy, mental health, outpatient services, veterans

Background

Mental health (MH) services are an important component of health care but are notably lacking in the workforce. The National Council Medical Director Institute estimates that 77% of counties in the United States do not have an adequate number of psychiatric providers.1 To make this problem worse, the number of psychiatrists treating the public sector and insured patients decreased by 10% in the United States from 2003 to 2013.2 Emergency departments across the country have typically been relied upon to treat these patients acutely with uncertain plans for chronic management.3 In March 2017, the National Council Medical Director Institute, authorized by the National Council for Behavioral Health, published a report titled “The Psychiatric Shortage, Causes and Solutions.”1 A call for increased access to MH services has been noted and, unfortunately, has not yet been met.4 This increase in demand combined with a decreased supply of psychiatric providers results in a significant strain on MH resources and significantly limited access for patients.

Typically, MH services are composed of treatment from 2 main modalities: pharmacotherapy (medication management) and psychotherapy (counseling and therapy). An increasing number of pharmacists are specializing in MH through psychiatric residency training programs to help combat the growing shortage of psychiatric prescribers.5-9 Clinical pharmacists who have completed a postgraduate year-2 residency in psychiatry are ideally positioned to increase access to comprehensive medication management as mental health clinical pharmacy specialist (MH-CPS) providers across the continuum of MH care. This training includes, but is not limited to, extensive psychopharmacology education, MH assessment training, disease state education, and supervised prescriptive authority under MH-CPS, psychiatrists, and other MH professionals for a wide scope of training. The Veterans Affairs (VA) system has played an active role in advancing the practice of MH-CPS in recent years.10

The inclusion of MH-CPS as a part of interdisciplinary care teams has enabled the VA to improve access to MH providers and optimize medication regimens with an MH-CPS serving as a primary provider in MH clinics. In early 2019, there were more than 426 MH-CPS at more than 119 VA facilities. Nearly 75 additional pharmacists complete MH-focused residencies each year at the VA. Between October 1, 2017, and September 30, 2018, there were more than 340 000 encounters completed by MH-CPS—an increase of 19% from the year prior.

From 2013 to 2016, the number of pharmacists with MH scopes of practice increased by 42% with MH encounters increasing by 221%. Integration of MH-CPS into such an active role in MH clinics has demonstrated both cost and time savings to the VA. Studies have shown that at least $4 in benefits are seen for every $1 invested in clinical pharmacy specialists (all specialties) in the general population.10

Although the VA is improving access to MH providers by allowing MH-CPS to practice at the top of their professional license (ie, performing MH assessments, providing medication management with prescriptive authority), it is essential that the quality of care veterans receive remains high across all disciplines with whom they come into contact. Additionally, it is equally important to the functioning of an interdisciplinary team that other providers involved in a patient's care value the MH-CPS for providing exceptional care in these roles. The need to evaluate the satisfaction of providers with MH-CPS in the VA system has not been as thoroughly explored as the pharmacoeconomic benefits. We set out to determine the impressions that those in other disciplines held about the MH-CPS.

Methods

Study Design

A survey was developed to present to providers (primarily psychiatrists, social workers, and psychologists) in MH team meetings in December 2018. The survey was designed to be anonymous across providers, disciplines, and treatment teams. Surveys were not presented to clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS) team members to avoid bias. During administration of the survey, the purpose, development, and ultimate intentions (quality improvement, publication of results) were explained before dissemination. This was followed by anonymous collection after allowing adequate time for completion. Providers were also given the option to return surveys anonymously through interoffice mail.

This survey utilized Likert scale criteria with 5 possible responses as follows: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree. Providers also had the option to answer not applicable for the questions presented. If this option was selected, that answer was excluded from the item analysis.

Eight statements were presented as follows:

I feel comfortable when my patients see a MH-CPS (in case of MD [medical doctor], in coverage).

My patients are comfortable seeing a MH-CPS for their care.

I believe that patients receive high quality care when seen by a MH-CPS.

Working with MH-CPS helps to expand my understanding of pharmacotherapy in psychiatric disease states.

MH-CPS receive adequate training to see patients in mental health clinics.

Having MH-CPS in the mental health clinics benefits the treatment team.

Utilizing MH-CPS in the mental health clinics improves access to care for patients.

Process improvement and quality improvement projects completed by MH-CPS add value to the care offered by the mental health clinics.

For the answers collected, each possible answer was given a point value from 1 to 5 for statistical analysis (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). An additional line was provided for individual comments.

Statistical Analysis

Likert scale responses were collected and analyzed to determine median scores. Free text additional comments were also evaluated individually.

Results

In total, 38 surveys were completed and collected. Responders included psychiatrists, social workers, psychologists, and a small set of social work and psychology trainees.

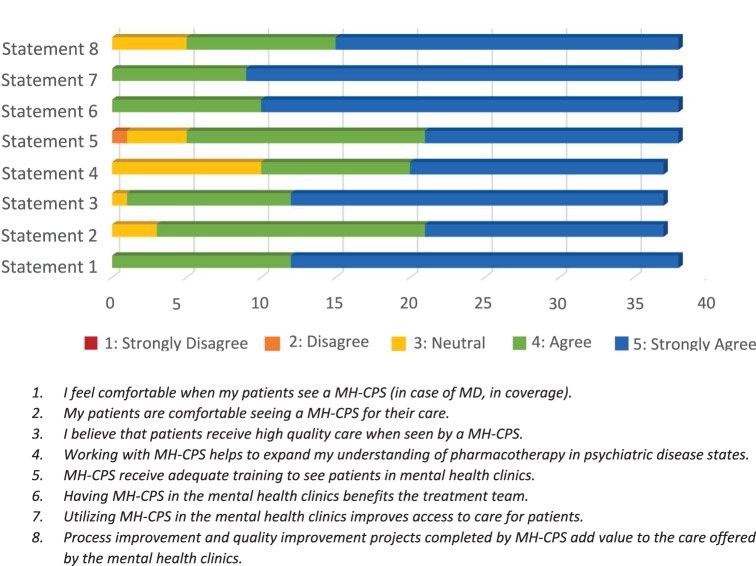

Answers to all statements were completed with only the exception of 2 not applicable responses (1 each to questions 2 and 4) and 1 response to question 3 that was left blank. The range of answers among all questions was between 2 and 5, broken down in the Figure.

FIGURE.

Results of the provider survey using the 8 listed statements; responses based on Likert scale criteria

The median results for each statement were all either 4 or 5, indicating either agree or strongly agree. Three responses had a median of 4 (questions 2, 4, and 5), and 5 had a median response of 5 (questions 1, 3, and 6 through 8). Additionally, the median across all responses for all components was 5, correlating with the response highly agree. Even the lowest scored statement score was overwhelmingly positive. This was on statement 4, which was related to understanding of psychopharmacology and improvements with MH-CPS team members. This lower response could be explained by the simple fact that those who completed the survey function more in direct patient care and less in time providing in-services and provider education. As a whole, the scores were generally unalarming and were a positive reflection of the role of MH-CPS.

Overall, additional free text comments were limited. In general, comments were positive with a few highlighting patient preferences for certain provider specialties. Other comments touched on differences between provider expertise and training background. No comments questioned the role of MH-CPS in the clinic or were negative in nature.

Discussion

The results of this survey were overwhelmingly supportive in nature and reflected a positive impression of MH-CPS in the MH clinic setting. Overall, MH team members rated satisfaction with MH-CPS highly across all evaluated criteria.

The simplicity and ease of use of this survey provided for a robust response and results that were easy to interpret clearly. By using a Likert scale, relatively subjective responses could be easily analyzed statistically in a meaningful way. Additionally, the range of disciplines surveyed provides a wide scope of opinions across disciplines. The results are a strong representation of the impression of providers who regularly work alongside MH-CPS at this particular practice site.

These results may be limited by some potential bias as those completing the surveys were coworkers of the MH-CPS referenced in the survey. However, it is the impression of the study team that these providers could truly speak to the role of the MH-CPS and provide accurate feedback. Anonymity was utilized to mitigate this potential risk bias as much as possible. Additionally, some questions on this survey relied on those completing the survey to have some knowledge of MH-CPS scopes of practice and training requirements, which may not be the case for every provider who participated. However, it is noted that not applicable could have been answered alternatively in these cases in which providers did not feel they had adequate information to provide an informed response. Overall, it is the impression of the study team that the responses obtained were an accurate representation of the general climate of the clinics involved. An additional limitation is the sample size of the survey population as it only included a small number of providers at 1 practice site. Therefore, these responses only reflect those of providers at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital & Clinics. This limitation could be alleviated in future studies by surveying multiple practice sites to get a larger pool of responses to more accurately represent the impressions of MH-CPS across the VA or in alternate practice settings.

As far as assessing areas for improvement, the explicit implications of this survey are limited. This survey did not directly address what areas for improvement in MH-CPS services may be present as the initial focus was on impressions of current services. With that in mind, some small areas for improvement can still be extrapolated from the results described in this study. For example, statement 4 had the lowest median response although still positive. This highlights a potential benefit to providing education to other clinicians about the training process and scope of MH-CPS and ways they may be able to help expand other team members' knowledge about pharmacotherapy in psychiatric disease states. Additionally, providing education to other providers about the training process and clinical scope of MH-CPS could be a potential area for improvement to foster improved team dynamics and cohesion. Otherwise, these results imply that the need for system-wide change is limited as the results were positive by the vast majority. Additional surveys or performance reviews may be better equipped to provide specific areas for improvement moving forward. However, self-improvement, continuing education, and sustained clinical practice experience would be beneficial for any CPS or health care provider and should always be encouraged.

For future investigation, this scale could be used to gauge impressions at another time point to compare ratings. It could also be considered (with slight modification) to evaluate other disciplines within MH or otherwise or to explore opportunities for CPS in other areas of practice. It would also be of interest to disperse this survey to more practice sites with similar practice models to gauge impressions across the VA in MH as well as other CPS areas.

Mental health clinical pharmacy specialists are a valued and respected part of the MH care team, which is demonstrated in these results. As a whole, the results of this survey support the role of MH-CPS in the MH clinic setting and are an encouraging reflection of the clinical pharmacy profession as a whole.

References

- 1.Levin A. Report details national shortage of psychiatrists and possible solutions. PN. 2017;52(8):1. doi: 10.1176/appi.pn.2017.4b24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop TF, Seirup JK, Pincus HA, Ross JS. Population of US practicing psychiatrists declined, 2003-13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(7):1271–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1643. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1643 PubMed PMID: 27385244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zun L. Care of psychiatric patients: the challenge to emergency physicians. WestJEM. 2016;17(2):173–6. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.1.29648. DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2016.1.29648 PubMed PMID: 26973743 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4786237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lake J. Urgent need for improved mental health care and a more collaborative model of care. Perm J. 2017;21:17–024. doi: 10.7812/TPP/17-024. DOI: 10.7812/tpp/17-024 PubMed PMID: 28898197 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5593510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finley PR, Crismon ML, Rush AJ. Evaluating the impact of pharmacists in mental health: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(12):1634–44. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.15.1634.31952. DOI: 10.1592/phco.23.15.1634.31952 PubMed PMID: 14695043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deslandes R, John DN, Deslandes PN. An exploratory study of the patient experience of pharmacist supplementary prescribing in a secondary care mental health setting. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2015;13(2):553. doi: 10.18549/pharmpract.2015.02.553. DOI: 10.18549/PharmPract.2015.02.553 PubMed PMID: 26131043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harms M, Haas M, Larew J, DeJongh B. Impact of a mental health clinical pharmacist on a primary care mental health integration team. Ment Health Clin [Internet] 2017;7(3):101–5. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2017.05.101. DOI: 10.9740/mhc.2017.05.101 PubMed PMID: 29955506 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6007568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herbert C, Winkler H. Impact of a clinical pharmacist-managed clinic in primary care mental health integration at a Veterans Affairs health system. Ment Health Clin [Internet] 2018;8(3):105–9. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2018.05.105. DOI: 10.9740/mhc.2018.05.105 PubMed PMID: 29955554 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6007641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen CE, Holmes S. Pharmacist's impact on chronic psychiatric outpatients in community mental health. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1978;35(6):704–8. PubMed PMID: 665683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office – Pharmacy Benefits Management Services. Clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS) role in mental health – Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration fact sheet. Washington: Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crosier M, Scott J, Steinfeld B. Improving satisfaction in patients receiving mental health care: a case study. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2012;39(1):42–54. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9252-0. DOI: 10.1007/s11414-011-9252-0 PubMed PMID: 21847711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]