Abstract

The PI3K-AKT-mTOR cascade is required for renal cell carcinoma (RCC) progression. SC66 is novel AKT inhibitor. We found that SC66 inhibited viability, proliferation, migration and invasion of RCC cell lines (786-O and A498) and patient-derived primary RCC cells. Although SC66blocked AKT-mTORC1/2 activation in RCC cells, it remained cytotoxic in AKT-inhibited/-silenced RCC cells. In RCC cells, SC66 cytotoxicity appears to occur via reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, sphingosine kinase 1inhibition, ceramide accumulation and JNK activation, independent of AKT inhibition. The ROS scavenger N-acetylcysteine, the JNK inhibitor (JNKi) and the anti-ceramide sphingolipid sphingosine-1-phosphate all attenuated SC66-induced cytotoxicity in 786-O cells. In vivo, oral administration of SC66 potently inhibited subcutaneous 786-O xenograft growth in SCID mice. AKT-mTOR inhibition, SphK1 inhibition, ceramide accumulation and JNK activation were detected in SC66-treated 786-O xenograft tumors, indicating that SC66 inhibits RCC cell progression through AKT-dependent and AKT-independent mechanisms.

Subject terms: Targeted therapies, Targeted therapies

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of renal malignancy1. Nephroureterectomy of early-stage RCC is the only possible curable treatment option1. However, RCC is more often diagnosed at an advanced stage, with 25% of patients developing local invasion and systematic metastasis resulting in a poor prognosis1. The PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway is frequently upregulated in RCC due to mechanisms that include PTEN mutation/depletion, PI3KCA mutation, and sustained activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs)2–5. Constitutive activation of this cascade is necessary for RCC cell proliferation, survival, migration, and metastasis, and also angiogenesis and resistance to anti-tumor treatments2,3,6,7. Molecularly-targeted agents are currently being utilized for the treatment of certain RCC patients, including the mTORC1 inhibitors Temsirolimus and everolimus, which are approved by the FDA for the treatment of advanced RCC2,3,6,7.

Our group has previously shown that targeted inhibition of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway is a valid treatment strategy in the management of RCC8–10. SF2523, a PI3K-AKT and bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) dual inhibitor, was found to potently inhibit RCC cell growth in vitro and in vivo8. Similarly, the AKT-mTORC1/2 inhibitor WYE-687 inhibited cell growth of human RCC cells9. In addition, we identified that microRNA-302c inhibited RCC cell proliferation by targeting Grb2-associated binding 2 (Gab2)-AKT signaling10.

Jo et al., developed SC6611, a novel allosteric AKT inhibitor that exerted a dual-inhibitory mechanism by inducing AKT ubiquitination and interfering with AKT pleckstrin homology (PH) domain binding to PIP311. The study by Cusimano et al., demonstrated that AKT inhibition by SC66 induced significant cytotoxic effects in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells12. In this study, we demonstrate that in addition to AKT-dependent RCC cell inhibition, SC66 inhibits RCC cell progression via AKT-independent mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Reagents and chemicals

SC66, MK-2206, and LY294002 were purchased from MCE Chemicals (Shanghai, China). N-acetylcysteine (NAC), PD98059, U0126, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and the JNK inhibitor (JNKi) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo). The broad caspase inhibitor z-VAD-cho and the caspase-3 inhibitor z-DEVD-cho were obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Shanghai, China). Antibodies for phosphorylated (“p”)-AKT (Ser-473) (#9271), AKT1/2 (#9272), p-S6K1 (#9234), S6K1 (9202), p-Erk1/2 (#9101), Erk1/2 (#9102), p-JNK (#9255), JNK1/2 (#9252), SphK1 (#12071), cleaved-caspase-3 (#9664), cleaved-caspase-9 (#20750), cleaved-poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (#5625), Bcl-2 (#15707), and β-tubulin (#15115) were purchased from Cell Signaling Tech (Beverly, MA).

Cell culture

The established RCC cells (786-O and A489 lines) and immortalized HK-2 tubule epithelial cells13,14 were cultured using the previous protocol10,15. Cells were routinely subjected to mycoplasma and microbial contamination examination. STR profiling, population doubling time, and morphology were routinely checked every 3–4 months to confirm the genotype. The primary human RCC cells, derived from three primary RCC patients (“RCC1/2/3”), as well as the primary human renal epithelial cells (“Ren-Epi”) were cultured in the described medium8,9. The written-informed consent was obtained from each enrolled patient. All investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Experiments and protocols were approved by the Ethics Review Board of Soochow University (Suzhou, China).

Methylthiazol tetrazolium (MTT) assay

Cells were seeded onto the 96-well tissue culture plates (3 × 103 cells per well). Following treatment, cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay. MTT OD was recorded at 490 nm.

Soft agar colony formation assay

Cells were seeded onto the 10-cm tissue culture dishes (1 × 104 cells per dish), treated with SC66 every two days for five rounds. Afterwards, the number of viable 786-O colonies were counted.

BrdU assay

Cells were seeded onto the six-well tissue culture plates (1 × 105 cells per well). Following treatment, cells were incubated with BrdU (10 μM, Cell Signaling Tech) for 8 h and then fixed. BrdU incorporation was determined in the ELISA format. BrdU OD at 405 nm was recorded.

EdU assay of cell proliferation

Cells were seeded onto the six-well tissue culture plates (1 × 105 cells per well). The EdU (5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine) Apollo-488 In Vitro Imaging Kit (Ribo-Bio, Guangzhou, China) was utilized to quantify cell proliferation. Following treatment EdU (2.5 μM) was added to RCC/epithelial cells for 6 h. Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst-33342 for 5 min, visualized under a fluorescent microscope (Leica). We counted at least 400 cells of six random views to calculate EdU ratio for each treatment.

In vitro cell migration and invasion assays

As described16,17 RCC cells (4 × 104 cells of each condition in 200 μL serum-free medium) were initially seeded onto the upper surfaces of “Transwell” chambers. The lower compartments were always filled with complete medium (containing 10% FBS). Following 24 h incubation, the migrated cells on the lower surface were fixed, stained and counted. Matrigel (Sigma) was added in the chamber surfaces when analyzing cell invasion.

Caspase activity assay

Assaying of caspase-3/-9 activity was described previously18. Twenty μg of cytosolic extracts of each treatment were added to the caspase assay buffer18 with the caspase-3 substrate or the caspase-9 substrate18. Release of 7-amido-4-(trifluoromethyl)-coumarin (AFC) was quantified by using a Fluoroskan system18. AFC optic density (OD) was recorded.

Annexin V FACS assay

As reported18, cells with the indicated treatment were washed and incubated with Annexin V-FITC (10 μg/mL) and propidium iodide (PI, 10 μg/mL) (Invitrogen), and detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using a Becton-Dickinson machine. Annexin V-positive cells were labeled as the apoptotic cells.

TUNEL assay

Cells were seeded onto the six-well tissue culture plates (1 × 105 cells per well). Following treatment, cells were incubated with TUNEL (Invitrogen, 10 μM) for 3 h. Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst-33342 for 5 min, visualized under a fluorescent microscope (Leica). For each treatment, we counted at least 400 cells of six random views (1×100 magnification) to calculate TUNEL ratio.

Western blotting assay

Cells and tumor tissues were incubated with RIPA lysis buffer (Biyuntian). Thirty micrograms of lysates per lane were separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore). After blocking, the blots were incubated with the applied primary and secondary antibodies. The enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (GE Healthcare) were added to the blots to detect the targeted protein bands. Quantification of the band intensity was performed with Quantity One 4.6.2 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

As described19, the ROS levels were tested by using the carboxy-H2DCFDA dye. Following treatment, cells were stained with carboxy-H2-DCFDA (10 μM) for 30 min under the dark. The DCF fluorescence was measured under 485 nm excitation and 525 nm emission using the Fluorescence machine (Thermo Scientific, Shanghai, China).

Glutathione content assay

Reduced glutathione (GSH) is one key scavenger of ROS, and its ratio with oxidized disulfide form glutathione (GSSG) can be used as a quantitative indicator of oxidative stress intensity20. Following treatment, cells were lysed. The ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) was measured using the GSH/GSSG assay kit (Beyotime).

Sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) activity assay

For each treatment, 200 μg lysates were incubated with 25 μM D-erythro-sphingosine in 0.1% Triton X-100, 2 mM ATP, and [γ-32P] ATP for 30 min at 37 °C21, stopped by adding 20 μL of HCl, plus 800 μL of chloroform/methanol/HCl (100:200:1, v/v). Afterwards, chloroform and KCl (250 μL each) were added, and centrifugation was performed to separate layer phases. The organic layer was dried and resuspended in chloroform/methanol/HCl21. Lipids were resolved on silica TLC plates in 1-butanol/acetic acid/water21. Labeled sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) spots were visualized by autoradiography and quantified by scraping and counting in a scintillation counter. SphK1 activity was evaluated as pmol/h/g protein.

Ceramide content assay

The cellular ceramide level was analyzed by the protocol reported early22, tested as fmol by nmol of phospholipids.

Mitochondrial depolarization

As described23 following stress-induced mitochondrial depolarization, JC-1 dye shall aggregate in mitochondria, forming green monomers24. RCC were seeded onto the 24-well tissue-culturing plates (1 × 104 cells per well). Following SC66 treatment cells were incubated with JC-1 (5 μg/mL) for 30 min, washed and tested immediately under a fluorescence spectrofluorometer at 550 nm.

AKT1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA)

AKT1 shRNA lentivirus (sc-29195V, Santa Cruz Biotech, 10 μL/mL medium) was added to 786-O cells for 24 h. Stable cells were selected by puromycin (5.0 μg/mL) for another 10 days. Expression of AKT1 in the stable cells was determined by Western blotting assay.

AKT knockout

The small guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting human AKT1 (Target DNA sequence, 5’-TCACGTTGGTCCACATCCTG) was inserted into the lenti-CRISPR-GFP-puro plasmid25. The construct was then transfected to 786-O cells by Lipofectamine 2000. FACS was performed to sort the GFP-positive 786-O cells. The resulting single cells were further cultured in the selection medium with puromycin (5 μg/mL) for 10 days. AKT1 knockout in stable cells was verified by Western blotting assay.

Xenograft model

Female CB-17 severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID) mice, 4–5 week old, 17–18 g, were provided by the Animal Center of Soochow University (Suzhou, China). 786-O cells (6 × 106 per mouse, in 200 μL DMEM/Matrigel, no serum) were subcutaneously (s.c.) injected into flanks. After three week, the xenografts, close to 100 mm3, were established (“Day-0”). Ten mice per group were treated once daily by gavage with either vehicle control or SC66 (10 or 25 mg/kg body weight) for 24 consecutive days. Every six days, the mice body weights and bi-dimensional tumor measurements18 were recorded. The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Soochow University and Ethics Review Board of Soochow University (Suzhou, China).

Statistical analysis

The investigators were blinded to the group allocation during all experiments. Results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis among different groups was performed via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Scheffe’s test using SPSS20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The two-tailed unpaired T test (Excel 2007) was applied to test the significance of the difference between two treatment groups. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

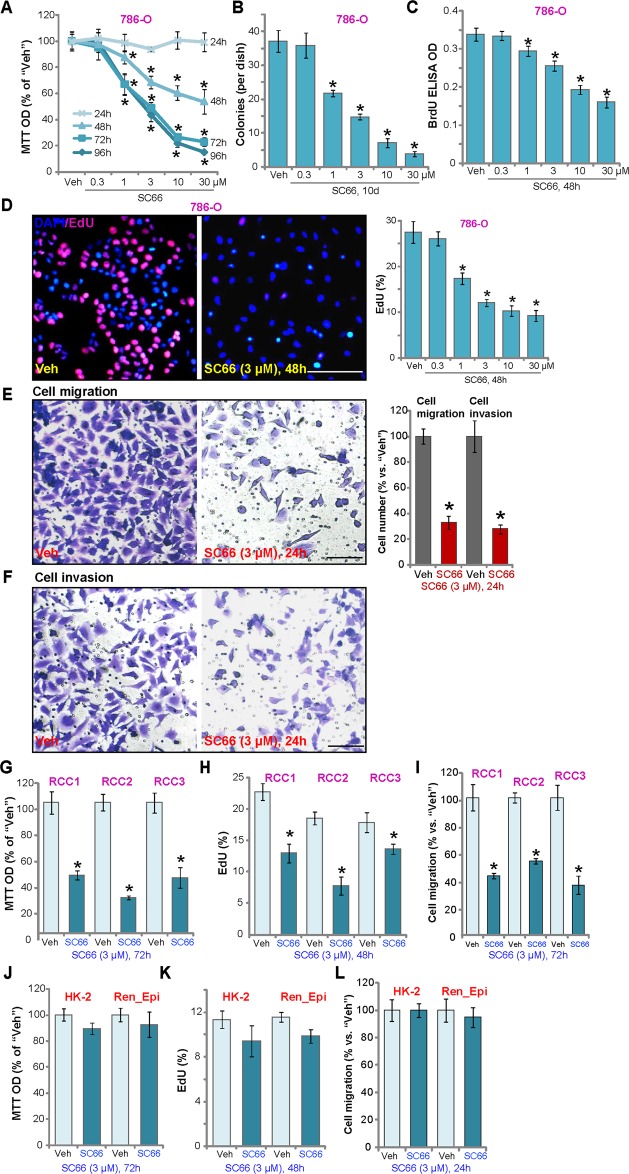

SC66 inhibits RCC cell progression in vitro

To study the mechanism of SC66 cytotoxicity cultured human RCC786-O cells8–10 were treated with different concentrations of SC66. The MTT assay of cell viability demonstrated that SC66 dose-dependently reduced the viability of 786-O cells (Fig. 1a), in a time-dependent manner that required at least 48 h to exert a significant effect (Fig. 1a). The IC-50 of SC66 was close to 3 μM at 72 h and 96 h (Fig. 1a), and soft agar colony studies demonstrated that SC66 (1–30 μM) significantly decreased the number of viable786-O cell colonies (Fig. 1b). Examining 786-O cell proliferation, both BrdU ELISA and EdU staining confirmed that SC66 inhibited nuclear BrdU incorporation (Fig. 1c) and EdU incorporation (Fig. 1d) in a dose dependent manner. Measuring cell migration and invasion, Transwell and Matrigel Transwell assays, respectively, demonstrated that SC66 (3 μM, 24 h) potently inhibited 786-O cell migration (Fig. 1e) and invasion (Fig. 1f) in vitro. Similar results were obtained with the A498 human RCC cell line8,9, where SC66 (3 μM, 48/72 h) decreased cell viability (Fig. S1A) and proliferation (Fig. S1B), and inhibited A498 cell migration and invasion (Fig. S1C, D).

Fig. 1. SC66 inhibits RCC cell progression in vitro.

786-O RCC cells (a–f), primary human RCC cells (“RCC1/RCC2/RCC3”, g–i), or HK-2 tubular epithelial cells (j–l), the primary human renal epithelial cells (“Ren_Epi”) (j–l) were treated with indicated concentration of SC66, cells were further cultured for applied time periods, cell functions, including cell survival, proliferation, migration and invasion were tested by the appropriate assays. For each assay, n = 5. Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). *P < 0.05 vs. DMSO (0.1%) vehicle (“Veh”, same for all Figures). In this figure, experiments were repeated three times, and similar results were obtained each time. Bar = 100 μm (d–f, h).

In the primary human RCC cells, derived from three RCC patients (“RCC1/RCC2/RCC3”), SC66 potently reduced viability (Fig. 1g) and decreased proliferation (Fig. 1h). Transwell results, Fig. 1i, showed that SC66 (3 μM, 24 h) significantly decreased the number of migrated RCC cells. In contrast, immortalized HK-2 tubular epithelial cells26,27 and the primary human renal epithelial cells (“Ren-Epi”, from Dr. Hu28) were resistant to SC66, showing no significant effect on viability, proliferation or migration (Fig. 1j–l).

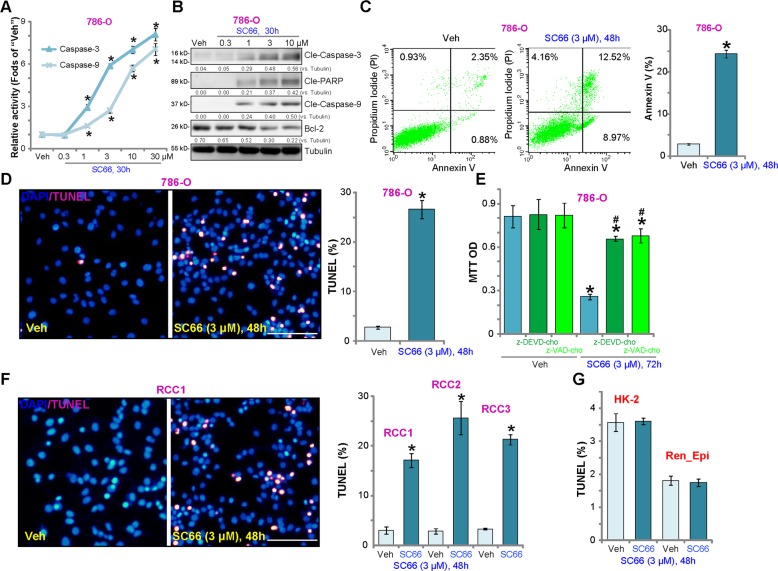

SC66 provokes apoptosis activation in RCC cells

Using the previously described methods8–10,15, we tested the effect of SC66 on cell apoptosis. As shown, SC66 dose-dependently increased the activities of caspase-3 and caspase-9 in 786-O cells (Fig. 2a). Analyzing apoptosis-associated proteins, SC66 (1–10 μM) induced cleavage of caspase-3, caspase-9, and PARP [poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase], and downregulatedBcl-2 (Fig. 2b). Annexin V FACS assay results demonstrated that SC66(3 μM) mainly induced apoptosis (Annexin V+/+) in 786-O cells (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, the percentage of cells with positive nuclear TUNEL staining was significantly increased following SC66 treatment (Fig. 2d). Significantly, co-treatment of the caspase-3 inhibitor z-DEVD-cho or the pan caspase inhibitor z-VAD-cho largely attenuated the SC66 (3 μM, 72 h)-induced viability reduction in 786-O cells (Fig. 2e). Similar results were observed in the A498 cell line (Fig. S1E–S1I). In primary human RCC cells (“RCC1/RCC2/RCC3”), treatment with SC66 induced apoptosis activation, as evidenced by a significant increase in nuclear TUNEL staining (Fig. 2f). In line with the above results showing that immortalized HK-2 tubular and primary renal epithelial cells are resistant to SC66, no significant apoptosis was detected (Fig. 2g).

Fig. 2. SC66 provokes significant apoptosis activation in RCC cells.

786-O RCC cells (a–e), primary human RCC cells (“RCC1/RCC2/RCC3”, f), HK-2 tubular epithelial cells (g), or the primary human renal epithelial cells (“Ren_Epi”) (g) were treated with indicated concentration of SC66, cells were further cultured for applied time periods, caspase-3/-9 activities (a), expression of apoptosis-associated proteins (b) and cell apoptosis (c–d, f, g) were tested by the mentioned assays. For e, 786-O cells were co-treated with 50 μM of the caspase-3 inhibitor z-DEVD-cho or the pan caspase inhibitor z-VAD-cho, and cell viability was tested by MTT assay. Expression of listed proteins were quantified, normalize to Tubulin (b). For each assay, n = 5. Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). *P < 0.05 vs. “Veh” group. #P < 0.05 vs. SC66 treatment only (e). In this figure, experiments were repeated three times, and similar results were obtained each time. Bar = 100 μm (d and f).

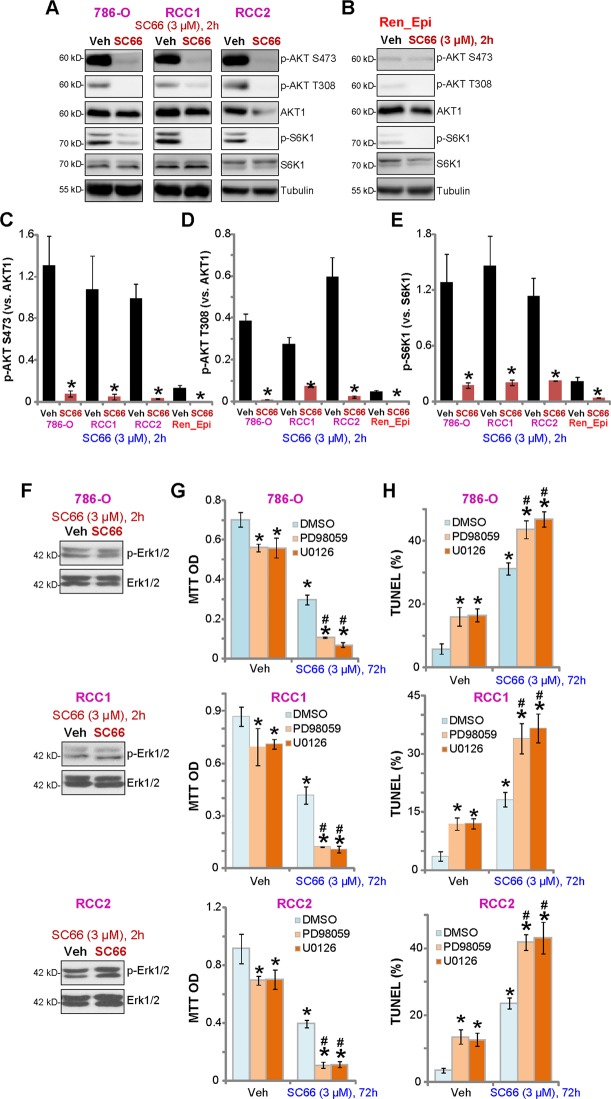

SC66 inhibits AKT-mTOR activation in RCC cells

As SC66 is reported to inhibit Akt in hepatocellular carcinoma cells11,12,29, we tested AKT and mTOR signaling in SC66-treated RCC cells. Western blot results demonstrated that phosphorylation of AKT (at both Ser-473 and Thr-308) and S6K1 (at Ser-389) were inhibited by SC66 (3 μM, 2 h) in both 786-O and primary RCC cells (“RCC1/RCC2”) (Fig. 3a). These results confirm that that SC66 acts to block AKT, mTORC1 (indicated by p-S6K130,31) and mTORC2 (indicated by p-AKT at Ser 47330,31) in RCC cells (Fig. 3a). Total AKT1 protein level was also decreased by SC66 treatment in RCC cells (Fig. 3a), possibly due to ubiquitin-mediated degradation11. Quantified results, integrating five sets of repeated blotting data in 786-O and primary RCC cells, show that SC66-induced significant AKT-mTORC1/2 inhibition (Fig. 3c–e). Basal AKT-mTORC1/2 activity was significantly lower in the primary renal epithelial cells (Fig. 3b–e), possibly explaining the ineffectiveness of this compound on normal epithelial cells (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 3. SC66 inhibits AKT-mTOR activation in RCC cells.

786-O cells, the primary human RCC cells (“RCC1/2”), or the renal epithelial cells (“Ren_Epi”) were treated with SC66 (3 μM) for 2 h, expression of listed proteins in total cell lysates were tested by Western blotting assay (a, b, and f).The quantified results integrating five sets of blotting data were presented (c–e). 786-O cells or RCC1/2 primary cells were treated with SC66 (3 μM), together with or without Erk inhibitor PD98059/U0126 (each at 5 μM), cells were further cultured for 72 h, and cell viability and apoptosis tested by MTT (g) and nuclear TUNEL staining (h) assays, respectively. Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). “DMSO” stands for 0.1% DMSO (g, h). *P < 0.05 vs. “Veh” group. #P < 0.05 vs. “DMSO” plus SC66 treatment (g, h). In this figure, experiments were repeated three times, and similar results were obtained each time.

As Erk signaling plays a role in RCC oncogenesis13,32–34, we examinedp-Erk1/2 at Thr202/Tyr204, finding that it was unchanged followingSC66 (3 μM, 2 h) treatment in 786-O and primary RCC cells (Fig. 3f). However, co-treatment with the Erk inhibitors, PD98059 and U0126, significantly potentiated SC66-induced viability reduction (Fig. 3g) and apoptosis (Fig. 3h). Treatment with the Erk1/2 inhibitors alone induced minor but significant cytotoxicity in the tested RCC cells (Fig. 3g, h). These results suggest that Erk inhibition could sensitize SC66-induced cytotoxicity in human RCC cells.

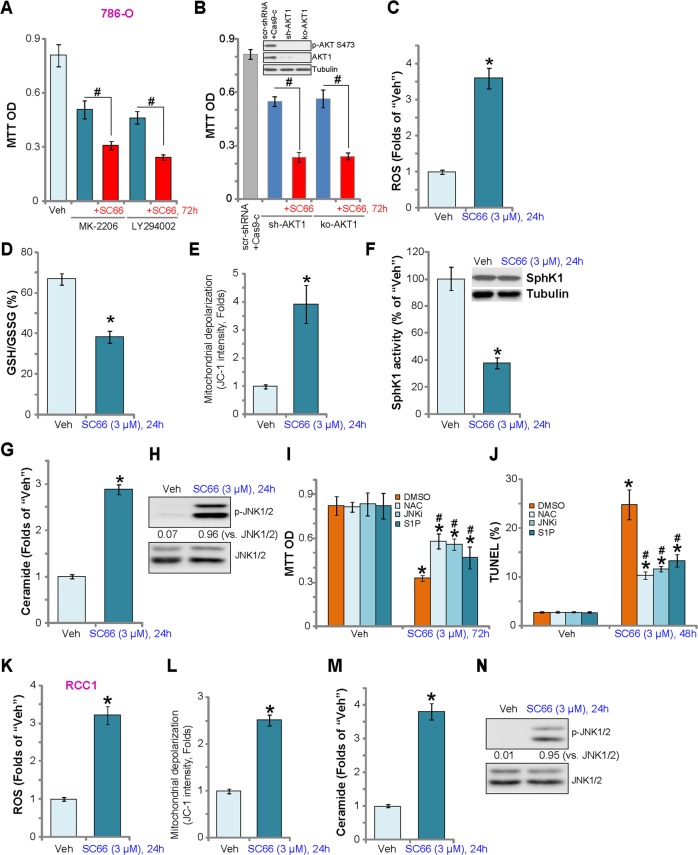

SC66 induces oxidative stress, SphK1 inhibition, and JNK activation in RCC cells

To examine whether SC66-induced cytotoxicity is primarily via Akt inhibition, we compared SC66 efficacy with known AKT inhibitors, including the AKT specific inhibitor MK-220635 and the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pan inhibitor LY29400236. MTT assay results (Fig. 4a) demonstrate that SC66 was more potent than MK-2206 and LY294002 in inhibiting786-O cell viability. Significantly, SC66 further reduced the viability of 786-O cells pretreated with MK-2206 and LY294002 (Fig. 4a), suggesting that SC66 effects are not limited to AKT inhibition. To confirm an AKT-independent mechanism of SC66 cytotoxicity in 786-O cells, shRNA and CRISPR/Cas9 methods were applied to silence and knockout AKT1, respectively (Fig. 4b, the upper panel). Results show that SC66 was cytotoxic in AKT1-silenced/-KO cells (Fig. 4b), indicating AKT-independent mechanisms of killing 786-O cells.

Fig. 4. SC66 induces oxidative stress, SphK1 inhibition, and JNK activation in RCC cells.

786-O cells were treated with MK-2206, LY294002 or plus SC66 (all at 3 μM), cells were further cultured, and cell viability was tested by MTT assay (a, 72 h). Stable 786-O cells with AKT1 shRNA (“sh-AKT1”) or CRISPR/Cas9 AKT1-KO construct (“ko-AKT1”), as well as the control cells with scramble control shRNA and Cas9 empty plasmid (“scr-shRNA+Cas9-c”), were tested by Western blotting assay of AKT expression (b, the upper panel), cells were treated with/without SC66 (3 μM) for 72 h, cell viability was tested (b, the lower panel). 786-O cells or the primary human RCC cells (“RCC1”) were treated with SC66 (3 μM) for indicated time periods, ROS production (c and k), GSH/GSSG ratio (d), mitochondrial depolarization (e and l), SphK1 expression and activity (f), as well as the ceramide contents (g and m) and p-/t-JNK expression (h and n) were tested by the appropriate assays. 786-O cells were pretreated for 30 min with NAC (400 μM), JNKi (10 μM), or S1P (10 μM), followed by SC66 (3 μM) treatment for 48 and 72 h, cell viability and apoptosis were tested by MTT assay (h) and TUNEL staining assay (i), respectively. Phosphorylated JNK1/2 was normalized to total JNK1/2 (h and n). For each assay, n = 5. Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). *P < 0.05 vs. “Veh” group. #P < 0.05 vs. SC66 treatment only (i, j). In this figure, experiments were repeated three times, and similar results were obtained each time.

Exploring possible AKT-independent mechanisms, we found that SC66 induced oxidative stress in 786-O cells, evidenced by increased ROS production (DCF-DA intensity increase, Fig. 4c) and reduced GSH/GSSG ratio (Fig. 4d). In addition, SC66 increased mitochondrial depolarization, tested by JC-1 green monomers formation (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) activity, an enzyme that prevents ceramide accumulation, was inhibited in SC66-treated 786-O cells (Fig. 4f) with a concomitant increase in ceramide levels (Fig. 4g). A consequence of ceramide accumulation is pro-apoptotic JNK activation37, and a significant increase of JNK1/2 phosphorylation was detected in SC66-treated cells, confirming JNK activation (Fig. 4h). To examine whether these pathways are involved in the cytotoxic action of SC66, we tested the effects of the ROS scavenger NAC, the JNK inhibitor JNKi, and anti-ceramide sphingolipidsphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P). As shown, SC66-induced viability reduction (Fig. 4i) and apoptosis (Fig. 4j) were inhibited by pretreatment with NAC, JNKi or S1P. In the primary human RCC cells (“RCC1”), SC66 treatment similarly reduced ROS production (Fig. 4k), mitochondrial depolarization (Fig. 4l), ceramide accumulation(Fig. 4m) and JNK activation (Fig. 4n). Thus, AKT-independent mechanisms participated in SC66-induced cytotoxicity in RCC cells.

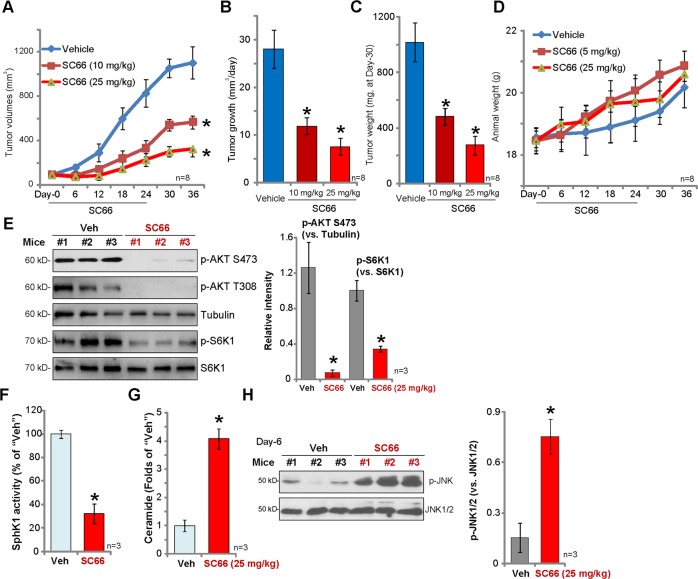

SC66 inhibits 786-O xenograft tumor growth in SCID mice

We tested the potential effect of SC66 in vivo using the previously-described 786-O xenograft tumor model8,9. 786-O cells were s.c. injected into the flanks of SCID mice and xenografts established within three weeks when tumors were around 100 mm3 (“Day-0”). We found that oral administration of SC66, at 10 and 25 mg/kg body weight, significantly inhibited tumor volume(Fig. 5a), and that daily tumor growth was significantly inhibited (Fig. 5b). At Day-36, tumors from all three groups were isolated and weighted individually.SC66-treated 786-O tumors weighted significantly less than the vehicle control tumors (Fig. 5c), while mouse body weights were not significantly different between the three groups (Fig. 5d). At treatment Day-6, two hours after SC66 (25 mg/kg) or vehicle administration, three 786-O tumors from each group (total six tumors) were isolated. Analyzing signaling changes, AKT-S6K phosphorylation was significantly inhibited in SC66-treated tumor lysates (Fig. 5e), confirming AKT-mTOR inhibition. In line with the in vitro findings, SC66 treatment decreased SphK1 activity (Fig. 5f), increased ceramide levels (Fig. 5g), and increased JNK activation (Fig. 5h).

Fig. 5. SC66 inhibits 786-O xenograft tumor growth in SCID mice.

786-O tumor-bearing SCID mice (eight mice per group, n = 8) were orally administrated with SC66 (10/25 mg/kg body weight, daily, for 24 days) or vehicle control (“Vehicle”), tumor volumes (a) and mice body weights (d) were recorded every 6 days. Estimated daily tumor growth was calculated as described (b). At Day-36, tumors were isolated and weighted (c). At treatment Day-6, two hours after SC66 (25 mg/kg) or vehicle administration, three 786-O tumors (n = 3) of each group (total six tumors) were isolated; Expression of listed proteins in tumor lysates was tested by Western blotting assays (e and h); The relative SphK1 activity (f) and ceramide contents (g) in tumor lysates were tested as well. The quantified results integrating all three sets of blotting data were presented (e and h). Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). *P < 0.05 vs. “Vehicle” group.

Discussion

Our study shows that SC66 inhibited cell viability, proliferation, migration and invasion in established (786-O and A498 lines) and primary human RCC cells.SC66 was found to inhibit AKT-mTORC1/2 activation and induce significant apoptosis in RCC cells. In contrast, this AKT inhibitor was non-cytotoxic to HK-2 epithelial cells and primary human renal epithelial cells with low basal AKT-mTORC1/2 activation. In vivo, SC66 oral administration, at well-tolerated doses, potently inhibited subcutaneous 786-O xenograft growth in SCID mice.

mTORC1 inhibitors are approved by FDA for the treatment of advanced RCC patients after failure of either sunitinib or sorafenib2,3. However, the use of mTORC1 inhibitors can have several drawbacks. First, the mTORC1 inhibitors, rapamycin and its analogs (“rapalogs”), only indirectly inhibit mTORC138,39. Second, mTORC1 inhibition can induce feedback activation of the PI3K-AKT and ERK-MAPK oncogenic pathways38–40. Third, rapalogs are unable to directly inhibit mTORC2, the latter being equally as important as mTORC1 in RCC progression. We have previously shown that WYE-687, a mTORC1/2 dual inhibitor, inhibited RCC cell growth with greater efficiency than mTORC1 inhibitors9. Further, the mTORC1/2 inhibitor, AZD2014, exerted more potent anti-RCC cell activity than rapalogs18. Similarly, the finding that SC66 can block AKT and mTORC1/2 activation in established and primary RCC cells is an advantage of this compound.

Furthermore, SC66 also exhibits cytotoxic actions independent of AKT1. Here, we show that in RCC cells SC66 induced ROS production, SphK1 inhibition, ceramide accumulation and JNK activation, which does not occur in RCC cells treated with the AKT specific inhibitor MK-220635,41 or in AKT1-silenced/-KO RCC cells. Significantly, the ROS scavenger NAC, the JNK inhibitor and anti-ceramide sphingolipid S1P all mitigated, but did not reverse, SC66-induced cytotoxicity in RCC cells. Importantly, confirming in vitro results, SphK1 inhibition, ceramide accumulation and JNK activation were detected in SC66-treated 786-O xenograft tumors. Therefore, SC66 acts through both AKT-dependent and AKT-independent mechanisms to exert more potent anti-RCC activity.

SphK1 is over-expressed and/or hyper-activated in RCC, promoting cancer progression42,43. SphK1 phosphorylates sphingosine to form S1P44,45, and SphK1 inhibition or silencing induces ceramide accumulation to promote cell apoptosis. Despite the importance of sphingolipid-derived signaling in tumorigenesis, there is a lack of potent and selective inhibitors of SphK. We found that SC66 inhibits SphK1 activation leading to pro-apoptotic ceramide accumulation and JNK activation in vitro and in vivo. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanism by which SC66 inhibits SphK1 in RCC cells.

It has been shown that Erk activation contributes to everolimus-acquired resistance and a poor prognosis in RCC patients33. Contrarily, Erk inhibition enhanced the efficacy of everolimus against RCC cells33. Yuen et al., found that AZD6244, an Erk inhibitor, at low doses augmented the antitumor activity of sorafenib34. In this study, we show that inhibition of Erk by PD98059 or U0126 potentiated SC66-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in 786-O and primary RCC cells, indicating that Erk activation could be a key resistance mechanism of SC66 in RCC cells.

Conclusion

In summary, we show that SC66 inhibits RCC cell progression in vitro and in vivo, through AKT-dependent and AKT-independent mechanisms. It should be noted that the findings of in vitro and animal RCC studies could not be directly translated to humans, and thus the efficacy and safety of SC66 need to be further investigated and confirmed.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81472776, 81773221, and 81773192), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20161222, BK20171248), by Suzhou Science and Technology Planed Projects (SYS201629), and the grant for Key Young Talents of Medicine in Jiangsu (QNRC2016875 and QNRC2016527), by Foundation of tumor clinical and basic research team of Affiliated Kunshan Hospital of Jiangsu University (KYC005) and by Jiangsu Province“333 Project” Research Projects (2016-III-0367).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by A. Stephanou

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ming Xu, Yin Wang, Li-Na Zhou, Li-jun Xu

Contributor Information

Dong-rong Yang, Email: doc_ydr@163.com.

Min-bin Chen, Email: cmb1981@163.com.

Jin Zhu, Email: urologistzhujin@163.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41419-020-2566-1).

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pal SK, Quinn DI. Differentiating mTOR inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013;39:709–719. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Husseinzadeh HD, Garcia JA. Therapeutic rationale for mTOR inhibition in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011;6:214–221. doi: 10.2174/157488411797189433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figlin RA, Kaufmann I, Brechbiel J. Targeting PI3K and mTORC2 in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: new strategies for overcoming resistance to VEGFR and mTORC1 inhibitors. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;133:788–796. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgio SL, et al. Perspectives on mTOR inhibitors for castration-refractory prostate cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2012;12:940–949. doi: 10.2174/156800912803251234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konings IR, Verweij J, Wiemer EA, Sleijfer S. The applicability of mTOR inhibition in solid tumors. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:439–450. doi: 10.2174/156800909788166556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motzer RJ, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu H, et al. Dual inhibition of BRD4 and PI3K-AKT by SF2523 suppresses human renal cell carcinoma cell growth. Oncotarget. 2017;8:98471–98481. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan XD, et al. Concurrent inhibition of mTORC1 and mTORC2 by WYE-687 inhibits renal cell carcinoma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu DH, et al. microRNA-302c-3p inhibits renal cell carcinoma cell proliferation by targeting Grb2-associated binding 2 (Gab2) Oncotarget. 2017;8:26334–26343. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jo H, et al. Deactivation of Akt by a small molecule inhibitor targeting pleckstrin homology domain and facilitating Akt ubiquitination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:6486–6491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019062108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cusimano A, et al. Cytotoxic activity of the novel small molecule AKT inhibitor SC66 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:1707–1722. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CM, et al. Alpha-Mangostin suppresses the metastasis of human renal carcinoma cells by targeting MEK/ERK expression and MMP-9 transcription activity. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017;44:1460–1470. doi: 10.1159/000485582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu X, et al. Inhibition of BRD4 suppresses cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017;41:1947–1956. doi: 10.1159/000472407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng B, et al. MiRNA-30a-mediated autophagy inhibition sensitizes renal cell carcinoma cells to sorafenib. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;459:234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang SS, et al. Triptonide inhibits human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell growth via disrupting Lnc-RNA THOR-IGF2BP1 signaling. Cancer Lett. 2019;443:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lv Y, et al. TBX2 over-expression promotes nasopharyngeal cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Oncotarget. 2017;8:52699–52707. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng B, et al. Pre-clinical evaluation of AZD-2014, a novel mTORC1/2 dual inhibitor, against renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;357:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di G, Wang Z, Wang W, Cheng F, Liu H. AntagomiR-613 protects neuronal cells from oxygen glucose deprivation/re-oxygenation via increasing SphK2 expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;493:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zitka O, et al. Redox status expressed as GSH:GSSG ratio as a marker for oxidative stress in paediatric tumour patients. Oncol. Lett. 2012;4:1247–1253. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu PH, et al. Identification of sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) as a primary target of icaritin in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:22800–22810. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gong L, et al. Bortezomib-induced apoptosis in cultured pancreatic cancer cells is associated with ceramide production. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014;73:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong H, et al. Dysregulation of cPWWP2A-miR-579 axis mediates dexamethasone-induced cytotoxicity in human osteoblasts. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;517:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks MM, Neelam S, Fudala R, Gryczynski I, Cammarata PR. Lenticular mitoprotection. Part A: monitoring mitochondrial depolarization with JC-1 and artifactual fluorescence by the glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibitor, SB216763. Mol. Vis. 2013;19:1406–1412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu F, et al. miR-1273g silences MAGEA3/6 to inhibit human colorectal cancer cell growth via activation of AMPK signaling. Cancer Lett. 2018;435:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan MJ, et al. HK-2: an immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cell line from normal adult human kidney. Kidney Int. 1994;45:48–57. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Komoike Y, Inamura H, Matsuoka M. Effects of salubrinal on cadmium-induced apoptosis in HK-2 human renal proximal tubular cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2012;86:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0742-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye XT, Huang H, Huang WP, Hu WL. LncRNA THOR promotes human renal cell carcinoma cell growth. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;501:661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran HT, Zhang S. Accurate prediction of the bound form of the Akt pleckstrin homology domain using normal mode analysis to explore structural flexibility. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2352–2360. doi: 10.1021/ci2001742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabatini DM. mTOR and cancer: insights into a complex relationship. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:729–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bitzer M, et al. Resminostat in combination with sorafenib as second-line therapy of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma-the SHELTER study. J Hepatol. 2016;65:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou Y, et al. ERK inhibitor enhances everolimus efficacy through the attenuation of dNTP pools in renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2019;14:550–561. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuen JS, et al. Combination of the ERK inhibitor AZD6244 and low-dose sorafenib in a xenograft model of human renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2012;41:712–720. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirai H, et al. MK-2206, an allosteric Akt inhibitor, enhances antitumor efficacy by standard chemotherapeutic agents or molecular targeted drugs in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1956–1967. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunn GJ, et al. Direct inhibition of the signaling functions of the mammalian target of rapamycin by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors, wortmannin and LY294002. EMBO J. 1996;15:5256–5267. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verheij M, et al. Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1996;380:75–79. doi: 10.1038/380075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 2017;168:960–976. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamming DW, Ye L, Sabatini DM, Baur JA. Rapalogs and mTOR inhibitors as anti-aging therapeutics. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:980–989. doi: 10.1172/JCI64099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi Y, Yan H, Frost P, Gera J, Lichtenstein A. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors activate the AKT kinase in multiple myeloma cells by up-regulating the insulin-like growth factor receptor/insulin receptor substrate-1/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase cascade. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1533–1540. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yap TA, et al. First-in-man clinical trial of the oral pan-AKT inhibitor MK-2206 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:4688–4695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pchejetski D, et al. FTY720 (fingolimod) sensitizes prostate cancer cells to radiotherapy by inhibition of sphingosine kinase-1. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8651–8661. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ader I, Brizuela L, Bouquerel P, Malavaud B, Cuvillier O. Sphingosine kinase 1: a new modulator of hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha during hypoxia in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8635–8642. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vadas M, Xia P, McCaughan G, Gamble J. The role of sphingosine kinase 1 in cancer: oncogene or non-oncogene addiction? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1781:442–447. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shida D, Takabe K, Kapitonov D, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Targeting SphK1 as a new strategy against cancer. Curr. Drug Targets. 2008;9:662–673. doi: 10.2174/138945008785132402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.