Abstract

Aims

The aim of this study was to estimate incidence of self-harm presentations to hospitals and their associated hospital costs across England.

Methods

We used individual patient data from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England of all self-harm presentations to the emergency departments of five general hospitals in Oxford, Manchester and Derby in 2013. We also obtained cost data for each self-harm presentation from the hospitals in Oxford and Derby, as well as population and geographical estimates from the Office for National Statistics. First, we estimated the rate of self-harm presentations by age and gender in the Multicentre Study and multiplied this with the respective populations to estimate the number of self-harm presentations by age and gender for each local Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) area in England. Second, we performed a regression analysis on the cost data from Oxford and Derby to predict the hospital costs of self-harm in Manchester by age, gender, receipt of psychosocial assessment, hospital admission and type of self-harm. Third, the mean hospital cost per age year and gender were combined with the respective number of self-harm presentations to estimate the total hospital costs for each CCG in England. Sensitivity analysis was performed to address uncertainty in the results due to the extrapolation of self-harm incidence and cost from the Multicentre Study to England.

Results

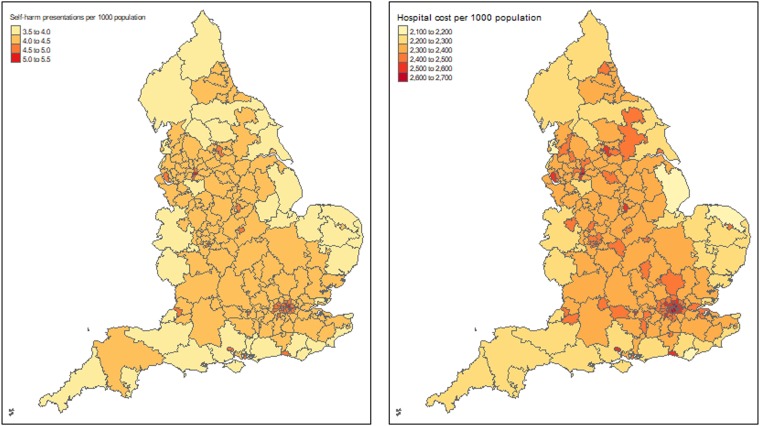

There were 228 075 estimated self-harm presentations (61% were female) by 159 857 patients in 2013 in England. The largest proportions of self-harm presentations were in the age group 40–49 years (30%) for men and 19–29 years (28%) for women. Associated hospital costs were approximately £128.6 (95% CI 117.8−140.9) million in 2013. The estimated incidence of self-harm and associated hospital costs were lower in the majority of English coastal areas compared to inland regions but the highest costs were in Greater London. Costs were also higher in more socio-economically deprived areas of the country compared with areas that are more affluent. The sensitivity analyses provided similar results.

Conclusions

The results of this study highlight the extent, hospital costs and distribution of self-harm presentations to hospitals in England and identify potential sub-populations that might benefit from targeted actions to help prevent self-harm and assist those who have self-harmed. They can support national as well as local health stakeholders in allocating funds and prioritising interventions in areas with the greatest need for preventing and managing self-harm.

Key words: Economic issues, emergency departments, health economics, incidence, suicide

Introduction

Self-harm, increasingly acknowledged as a major public health concern (Borschmann et al., 2018; Pilling et al., 2018; The Lancet Public, 2018; Ayre et al., 2019), is a key area in the national suicide prevention strategies of many countries and is a priority area in the Mental Health Gap Action Programme produced by the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2008). People who self-harm are at elevated risk of premature death (Hawton et al., 2006; Bergen et al., 2012; Carr et al., 2017), especially by suicide (i.e. death by intentional self-harm) (Bergen et al., 2012; Carroll et al., 2014; Olfson et al., 2018), and poor mental health, including depression and substance abuse (Da Cruz et al., 2011; Mars et al., 2014; Borschmann et al., 2017).

In England, prevention of self-harm and suicide is a priority area in public health policy, being the focus of national strategy and clinical guidelines (NICE, 2011; UK Government, 2012, 2019). It was highlighted as a key issue in its own right when the national suicide prevention strategy in England was updated in 2017 and its prevention was recognised as fundamental priority for all organisations involved in delivering the strategy (HM Government, 2019). Furthermore, the first ever Minister of Mental Health, Inequalities and Suicide Prevention was appointed in 2018 along with increased funding for suicide prevention (GOV.UK, 2018). In a series of policy initiatives, local NHS organisations and local government have been asked to draw up joint plans, according to guidelines from Public Health England, to reduce suicide by 10% in 2020 (Appleby et al., 2017; NHS England, 2018). Although suicide rates are strongly related to self-harm rates (Geulayov et al., 2018), hospital management of self-harm remains variable across the country and there has until recently been little sign of service improvement over time (Cooper et al., 2013).

Although the overall incidence of self-harm in England has been estimated previously (Hawton et al., 2007; Geulayov et al., 2016), little is known about its distribution across England. The only available nationwide estimates of self-harm incidence at local level are reported by Public Health England based on hospital admissions, which underestimate the scale of the problem (Clements et al., 2016; Public Health England, date accessed 27/02/2018). Besides the impact on population health, self-harm has considerable implications for healthcare costs, including costs of medical, psychiatric and social care (Sinclair et al., 2011a). A recent UK study based on a single centre estimated hospital costs to be on average £809 per self-harm presentation, with an approximate extrapolation to England of an impact on the NHS budget of approximately £162 million each year (Tsiachristas et al., 2017). This is a concerning figure for local health service commissioners, which increasingly face budget constraints and pressure to improve efficiency in healthcare organisation and delivery.

Estimating the incidence of self-harm presentations to hospitals and the associated hospital costs at a local level is key for designing services for individuals who self-harm and in planning hospital budgets. The aim of this study was to estimate the incidence of self-harm presentations to hospitals at both local and national levels and the associated hospital costs across England.

Methods

Study setting and primary data

The data were collected as part of the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. The three centres in the study have been collecting comprehensive data on hospital presentations for self-harm for many years, using similar methodology. The Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England was established early this century in order to provide more representative data on self-harm than each individual centre could provide. In this respect the three cities have a broad geographical distribution, with Oxford in South-East England, Derby in the East-Midlands and Manchester in North-West England. Oxford, Manchester and Derby also have distinctly different profiles in terms of the extent of socio-economic deprivation of their individual catchment areas. Based on the 2015 ratings of the Index of Multiple Deprivation scores for England, which range from 1 (worst) to 209 (best) across England, Manchester was ranked 5 (worst), Derby 55 and Oxford 166 (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015). While this does not entirely ensure that the study is fully representative of England as a whole, it means that the data on self-harm are far more representative than those from single centres.

The provision of mental health care in general hospitals in England is mainly limited to that focussed on general medical patients with mental health problems and patients who present following self-harm. This includes both care while patients are in hospital and coordinating care after hospital discharge, such as psychological support (e.g. for cancer patients). The overall provision of mental health-related care is funded through general government funds allocated to NHS England. With regards to self-harm, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends provision of a psycho-social assessment for all patients who present with self-harm to the emergency departments of general hospitals (NICE, 2011). This assessment is conducted by a member of the hospital mental health team and is focussed on assessing patients' problems, needs and risks to determine their subsequent care after leaving hospital. As other specialised mental health care is generally provided by separate community and other mental health teams and is therefore not part of our study. Since there are virtually no emergency departments in private hospitals in England, the cost of self-harm in private hospitals was not included in our study.

Adopting the working definition of the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England, which is used nationally in England (NICE, 2011), self-harm was defined as intentional self-injury or self-poisoning, irrespective of type of motivation or degree of suicidal intent. Self-poisoning was defined as the intentional self-administration of more than the prescribed or recommended dose of any drug (e.g. analgesics, antidepressants), and includes poisoning with non-ingestible substances (e.g. household bleach), overdoses of ‘recreational drugs’ and severe alcohol intoxication where clinical staff consider such cases to be acts of self-harm. Self-injury was defined as any injury that has been deliberately self-inflicted (e.g. self-cutting, jumping from height). Identification of cases was determined by clinical and research staff using these criteria.

The data included individual patient level data for all self-harm presentations to the emergency departments of five general hospitals (one in Oxford, three in Manchester and one in Derby) between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2014. The information collected included: overall self-harm method (i.e. self-poisoning, self-injury, both), specific self-harm method (e.g. cutting, poisoning by specific drugs), hospital admission and patient socio-demographic characteristics (i.e. age, gender and ethnicity). It also included the provision of psychosocial assessment. We also obtained the actual hospital cost (i.e. direct and indirect costs of all hospital services) of each self-harm presentation in our dataset (i.e. in 2013/14 fiscal year) from the finance departments of the hospitals in Oxford and Derby. Mid-year 2013 population estimates for the study catchment areas by single year of age and gender, as well as suicide rates and proportion of the catchment area populations living in rural areas were retrieved at Clinical Commissioning Group level from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Data on the Market Forces Factor (an index that adjusts price differences across the country) in Oxford, Manchester and Derby were retrieved from NHS England.

Approximating the incidence of self-harm presentations to hospitals across England

The number of self-harm presentations was divided by the total population in the catchment area of the three centres of the Multicentre Study for single age years and gender to estimate the rate of self-harm presentation to hospital by age and gender in 2013. This rate was multiplied by the population per age year and gender in each local health service commissioning area (known as Clinical Commissioning Groups – CCGs) in England to estimate the number of self-harm presentations in each CCG nationally by age and gender. The total number of self-harm presentations per CCG area in England was calculated by summing all self-harm presentations by age and gender.

Exploring heterogeneity in hospital costs in the multicentre study

Heterogeneity in costs among hospitals may be explained by patient case-mix (i.e. hospitals provide medical services to patients of different severity and medical needs), mix and quality of services provided (i.e. hospitals may provide services differently for the same need for care and their quality may vary) and production constraints (i.e. hospitals may have different prices for capital and labour inputs) (Street et al., 2010). We explored differences in patient case-mix between the three centres in terms of patient socio-demographic characteristics, overall and specific methods of self-harm and number of self-harm presentations during the study period. For this purpose, descriptive statistical analysis (i.e. frequencies, measures of central tendency and variability) was performed and differences between the three centres were tested with ANOVA and Kruskal−Wallis for continuous variables and chi-squares for categorical variables. In a subgroup descriptive analysis, we additionally compared the occupational status of those patients who had received psychosocial assessment between the three centres. Furthermore, we explored the variation in provided services (i.e. hospital admission and provision of psychosocial assessment) across the three centres using a descriptive statistical analysis. Mixed-Effects Generalised Linear Models were specified to estimate odds ratios for hospital admission and provision of psychosocial assessment adjusted for patient case-mix in order to explore differences in quality of care for self-harm between the three centres. Production constraints were accounted in our study by using the Market Forces Factor to adjust for unavoidable and location-specific cost differences (e.g. differences in land, buildings and staff costs) between the hospitals included in the Multicentre Study.

Estimating hospital costs of self-harm across England

Hospital cost data from Derby did not include the costs of psychosocial assessment. Therefore, we added £392 for patients younger than 18 years and £228 for adult patients to the hospital costs of those patients who had received psychosocial assessment in Derby. These unit costs were published recently and were close to the national average costs of psychosocial assessment reported by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (Tsiachristas et al., 2017). Furthermore, hospital cost data for each self-harm presentation in Oxford and Derby were regressed by gender, age, receipt of psychosocial assessment, hospital admission and general type of self-harm using a generalised linear model with Gamma distribution, log link and standard errors adjusted for clustering of episodes in patients. The coefficients of this regression analysis were fitted to the data from Manchester to estimate the hospital costs of self-harm presentations in Manchester after adjusting further for the Market Forces Factors. Using the hospital cost of all self-harm presentations in the dataset, we then calculated the mean hospital costs per self-harm presentation by age year and gender. The total costs of self-harm in each CCG area in England were then estimated by multiplying the estimated mean hospital costs per self-harm episode by age and gender with the estimated number of self-harm episodes in each CCG by gender and age.

Sensitivity analysis

Monte-Carlo simulation with 10 000 iterations was performed using the regression coefficients and standard errors from the generalised linear model to address the uncertainty in the results caused by predicting the hospital costs of self-harm presentations in Manchester. The uncertainty based on the simulation was displayed as 95% confidence intervals of the estimated hospitals costs across England. Furthermore, two univariate sensitivity analyses were performed to address the uncertainty in the national estimates of self-harm incidence and related hospital costs from the extrapolation of the Multicentre study. In the first, we used gender-specific and age standardised rates of suicide in each CCG between 2012 and 2014 to adjust the estimated number of self-harm presentations. To do this, we multiplied the estimated number of self-harm presentations by an adjustment factor. The suicide adjustment factor (by gender) was calculated by dividing the age standardised suicide rate in each CCG area by the average age standardised suicide rate in the three centres of the Multicentre Study. The underlying assumption for performing this sensitivity analysis was that suicide (i.e. death by intentional self-harm) and self-harm have common risk factors (Hawton et al., 2012) and there is evidence showing a strong positive relationship between rates of self-harm and suicide (Geulayov et al., 2018). Given that the method used to estimate the incidence of self-harm in the present study was based on data from largely urban areas in the Multicentre Study, a second univariate sensitivity analysis was performed by adjusting the estimated number of self-harm presentations in each CCG based on the rural/urban classification. For this, we used a rurality adjustment factor (by gender) for each CCG to account for approximately 31% lower self-harm presentations in males and 26% in females in rural areas compared with urban areas in England (Harriss and Hawton, 2011).

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study reviewed the study proposal, awarded funding and monitored the conduct of the study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

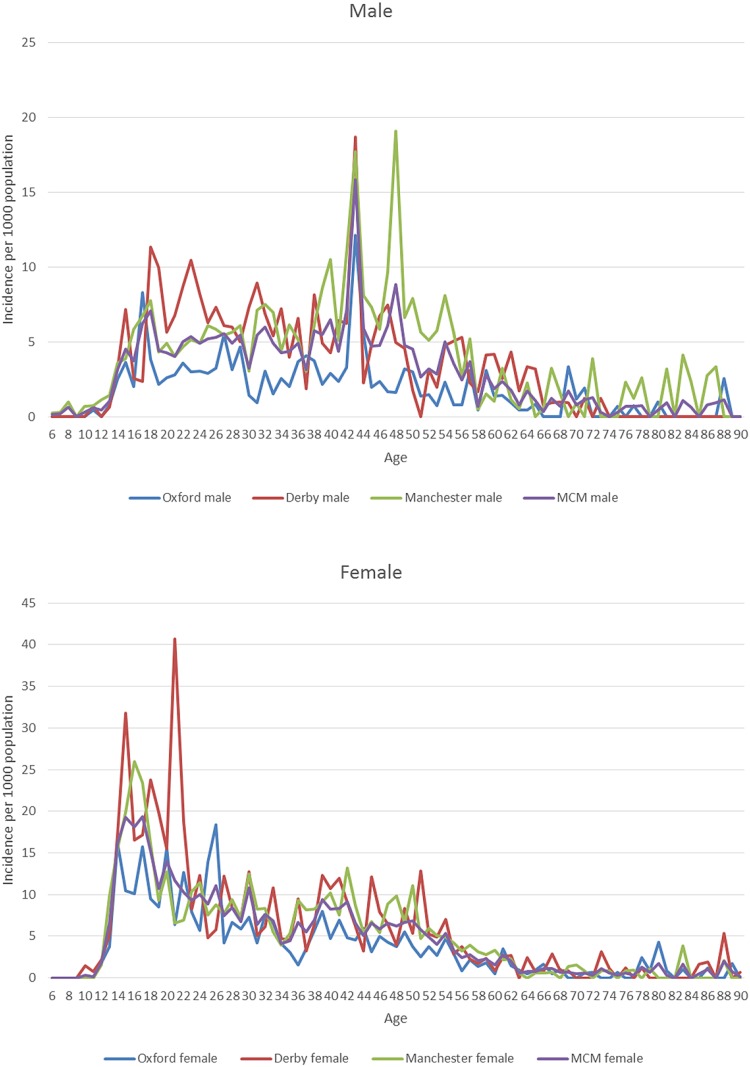

The results in panel A of Table 1 show that the sample in Manchester included proportionally fewer patients younger than 20 years (2 percentage points) and less females (5 percentage points) compared to the other two settings, while there were proportionally more patients of White ethnicity in Oxford (10 percentage points) compared to Manchester and Derby. The percentage of people having two or more self-harm repetitions in 2013 was higher in Derby (9%) followed by Oxford (7%) and Manchester (6%). Among the three centres, the proportion of episodes of self-harm involving self-poisoning alone ranged from 63% in Manchester to 76% in Derby, the proportion in which cutting was the method of self-injury ranged from 65% in Oxford to 80% in Derby, the proportion of self-poisoning episodes involving paracetamol or paracetamol-containing compounds ranged from 27% in Manchester to 33% in Derby (panel B of Table 1). The proportion of self-harm episodes in which a psychosocial assessment was conducted ranged from 50% in Manchester to 73% in Oxford, while admissions to hospitals ranged from 37% of episodes in Manchester to 78% in Oxford. The rate of self-harm presentations per 1000 population was highest in Manchester, except for the age groups 19–29 years, 30–39 years and 60–69 years where it was highest in Derby (panel C of Table 1). More detailed information about the variation in patient case-mix, service provision, self-harm rates and Market Force Factors between the three centres is provided in Appendices 1–5.

Table 1.

Variation in patients and self-harm episodes across the three centres of the multicentre study

| Variable | Oxford | Manchester | Derby |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Patient characteristics at first self-harm episode | |||

| n (% of 1150) | n (% of 3018) | n (% of 1548) | |

| Age (years)*** | |||

| <18 | 171 (15) | 381 (13) | 216 (14) |

| 18–19 | 80 (7) | 196 (7) | 116 (8) |

| 20–29 | 335 (29) | 946 (31) | 416 (27) |

| 30–39 | 190 (17) | 615 (20) | 273 (18) |

| 40–49 | 188 (16) | 499 (17) | 312 (20) |

| 50–59 | 111 (10) | 265 (9) | 131 (9) |

| 60–69 | 47 (4) | 65 (2) | 54 (3) |

| 70 and older | 27 (2) | 45 (2) | 30 (2) |

| Missing | 1 (0) | 6 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sex *** | |||

| Male | 446 (39) | 1326 (44) | 606 (39) |

| Female | 704 (61) | 1692 (56) | 942 (61) |

| Ethnicity*** | |||

| White | 1006 (87) | 2313 (77) | 1196 (77) |

| Black | 19 (2) | 69 (2) | 14 (1) |

| Asian | 33 (3) | 134 (4) | 30 (2) |

| Other | 52 (5) | 216 (7) | 49 (3) |

| Missing | 40 (3) | 286 (10) | 259 (17) |

| Number of self-harm repetitions* | |||

| 0 | 944 (82) | 2500 (83) | 1240 (80) |

| 1 | 123 (11) | 327 (11) | 175 (11) |

| 2 | 33 (3) | 91 (3) | 73 (5) |

| >2 | 50 (4) | 100 (3) | 60 (4) |

| Panel B: Type of self-harm and services provided at all self-harm episodes | |||

| Type of self-harm*** | n = 1664 | n = 4078 | n = 2208 |

| Self-poisoning alone | 1155 (69) | 2573 (63) | 1673 (76) |

| Self-injury alone | 395 (24) | 1266 (31) | 433 (20) |

| Both self-poisoning & self-injury | 114 (7) | 239 (6) | 102 (4) |

| Self-injury method*** | n = 508 | n = 1505 | n = 524 |

| Cutting/stabbing | 332 (65) | 1024 (68) | 422 (80) |

| Jump from height | 11 (2) | 33 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Hanging/asphyxiation | 45 (9) | 162 (11) | 45 (9) |

| Traffic related | 5 (1) | 47 (3) | 3 (1) |

| Other method# | 115 (23) | 239 (16) | 46 (9) |

| Self-poisoning | n = 963 | n = 2029 | n = 226 |

| Paracetamol | 214 (22) | 431 (21) | 376 (27) |

| Paracetamol compound | 57 (6) | 124 (6) | 76 (6) |

| Antidepressants | 139 (14) | 249 (12) | 149 (11) |

| Benzodiazepines | 46 (5) | 87 (4) | 68 (3) |

| Major tranquilisers | 26 (3) | 65 (3) | 46 (3) |

| Other | 338 (35) | 741 (37) | 440 (32) |

| Multiple drug groups | 143 (15) | 332 (16) | 226 (16) |

| Received psychosocial assessment*** | n = 1664 | n = 4078 | n = 2208 |

| No | 443 (27) | 2026 (50) | 731 (33) |

| Yes | 1221 (73) | 2052 (50) | 1475 (67) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Admitted to hospital*** | n = 1664 | n = 4078 | n = 2208 |

| No | 360 (22) | 2352 (58) | 921 (42) |

| Yes | 1300 (78) | 1489 (37) | 1211 (55) |

| Missing | 4 (0) | 237 (6) | 76 (3) |

| Panel C: Self-harm rate per 1000 population | |||

| Age | |||

| 10–18 | 4.97 | 7.98 | 7.00 |

| 19–29 | 6.27 | 7.02 | 10.70 |

| 30–39 | 3.81 | 6.82 | 6.89 |

| 40–49 | 4.25 | 9.15 | 7.26 |

| 50–59 | 2.22 | 5.04 | 4.02 |

| 60–69 | 0.98 | 1.28 | 1.87 |

| 70+ | 0.61 | 0.88 | 0.50 |

| Total | 3.61 | 6.29 | 5.98 |

*p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.0001; # other methods include: drowning, gunshot, gas, head banging.

As Table 2 shows, there were an estimated 228 075 self-harm presentations (39% males and 61% females) by 159 857 patients in 2013 in England. The highest proportion of self-harm presentations among males was in the 40–49 year age group (30%), while for females the 19–29 year age group had the highest percentage of presentations (28%). Based on the two univariate sensitivity analyses, estimated self-harm presentations in England were 215 588 after adjusting for suicide rates and 225 172 after adjusting for rurality.

Table 2.

Estimated incidence of self-harm in England in 2013 by gender and age group

| Age | 10–18 | 19–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70+ | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodes | ||||||||

| Males | 8911 (10%) | 19 950 (23%) | 16 782 (19%) | 26 218 (30%) | 10 654 (12%) | 3878 (4%) | 1644 (2%) | 88 038 (100%) |

| Females | 30 040 (21%) | 38 805 (28%) | 24 460 (17%) | 26 904 (19%) | 13 951 (10%) | 3602 (3%) | 2274 (2%) | 140 037 (100%) |

| Total | 38 951 (17%) | 58 756 (26%) | 41 242 (18%) | 53 123 (23%) | 24 605 (11%) | 7480 (3%) | 3918 (2%) | 228 075 (100%) |

| Patients | ||||||||

| Males | 7487 (12%) | 15 629 (25%) | 12 491 (20%) | 14 978 (24%) | 7663 (12%) | 3180 (5%) | 1586 (3%) | 63 014 (100%) |

| Females | 22 418 (23%) | 23 929 (25%) | 16 210 (17%) | 18 553 (19%) | 10 343 (11%) | 3291 (3%) | 2099 (2%) | 96 843 (100%) |

| Total | 29 905 (19%) | 39 559 (25%) | 28 701 (18%) | 33 531 (21%) | 18 006 (11%) | 6470 (4%) | 3685 (2%) | 159 857 (100%) |

| Episodes (sensitivity analysis-suicide rate adjustment) | ||||||||

| Males | 9233 (10%) | 20 670 (23%) | 17 387 (19%) | 27 164 (30%) | 11 038 (12%) | 4018 (4%) | 1703 (2%) | 91 213 (100%) |

| Females | 26 681 (21%) | 34 465 (28%) | 21 724 (17%) | 23 895 (19%) | 12 391 (10%) | 3199 (3%) | 2020 (2%) | 124 375 (100%) |

| Total | 35 913 (17%) | 55 135 (26%) | 39 111 (18%) | 51 059 (24%) | 23 429 (11%) | 7217 (3%) | 3723 (2%) | 215 588 (100%) |

| Episodes (sensitivity analysis-rural area adjustment) | ||||||||

| Males | 8749 (10%) | 19 817 (23%) | 16 685 (19%) | 25 755 (30%) | 10 415 (12%) | 3762 (4%) | 1592 (2%) | 86 775 (100%) |

| Females | 29 575 (21%) | 38 633 (28%) | 24 302 (17%) | 26 474 (19%) | 13 687 (10%) | 3511 (3%) | 2218 (2%) | 138 397 (100%) |

| Total | 38 324 (17%) | 58 450 (26%) | 40 987 (18%) | 52 229 (23%) | 24 099 (11%) | 7273 (3%) | 3810 (2%) | 225 172 (100%) |

The estimated hospital cost of self-harm in England in 2013 was approximately £128.6 (95% CI 117.8−140.9) million. In absolute terms, the majority of costs were for episodes involving women and were greatest in the Midlands and East regions (Table 3). The total hospital costs of self-harm reduced to £121.6 (95% CI 111.6−133.4) million or £127 (95% CI 116.4−139.7) million after independently adjusting for suicide rates and rurality, respectively, and assuming that the representativeness of the patients recorded in the Multicentre Study of Self-harm to all patients who self-harmed in England in the same period was not perfect.

Table 3.

Hospital cost of self-harm across large geographic areas in England (£, 2013)

| Males | Females | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| Main analysis | |||

| England | 49 559 150 (43 896 127 to 56 429 207) | 79 046 705 (70 310 153 to 89 561 701) | 128 605 855 (117 835 026 to 140 934 979) |

| North of England | 13 887 113 (12 303 350 to 15 805 226) | 22 301 908 (19 843 575 to 25 260 926) | 36 189 021 (33 162 982 to 39 653 206) |

| Midlands and East of England | 14 893 788 (13 193 223 to 16 957 069) | 23 776 299 (21 161 598 to 26 925 731) | 38 670 087 (35 442 360 to 42 360 185) |

| London | 8 189 719 (7 251 950 to 9 326 903) | 12 933 335 (11 470 902 to 14 688 055) | 21 123 054 (19 331 828 to 23 179 317) |

| South of England | 12 588 530 (11 149 072 to 14 336 034) | 20 035 163 (17 831 861 to 22 684 533) | 32 623 693 (29 894 968 to 35 745 008) |

| Sensitivity analysis-suicide rate adjustment | |||

| England | 51 388 469 (45 485 739 to 58 231 335) | 70 237 351 (62 504 833 to 79 697 099) | 121 625 820 (111 606 263 to 133 361 503) |

| North of England | 16 404 748 (14 524 117 to 18 586 623) | 20 697 182 (18 424 508 to 23 477 638) | 37 101 930 (34 065 729 to 40 658 786) |

| Midlands and East of England | 15 052 615 (13 327 277 to 17 055 894) | 19 248 590 (17 140 557 to 21 828 818) | 34 301 205 (31 492 938 to 37 593 516) |

| London | 8 196 243 (7 256 170 to 9 285 758) | 12 939 213 (11 486 205 to 14 715 577) | 21 135 456 (19 358 303 to 23 219 012) |

| South of England | 13 383 772 (11 848 737 to 15 170 634) | 20 571 587 (18 318 112 to 23 333 386) | 33 955 359 (31 155 554 to 37 244 280) |

| Sensitivity analysis-rural area adjustment | |||

| England | 49 040 989 (43 497 765 to 55 798 083) | 78 221 350 (69 455 479 to 88 833 331) | 127 262 339 (116 429 823 to 139 715 863) |

| North of England | 13 933 703 (12 359 729 to 15 851 916) | 22 331 294 (19 836 612 to 25 351 426) | 36 264 997 (33 188 797 to 39 811 304) |

| Midlands and East of England | 14 390 659 (12 763 144 to 16 373 060) | 23 087 662 (20 516 168 to 26 206 271) | 37 478 321 (34 304 814 to 41 130 411) |

| London | 8 721 310 (7 731 182 to 9 910 935) | 13 595 724 (12 037 830 to 15 485 045) | 22 317 035 (20 397 794 to 24 524 751) |

| South of England | 11 995 316 (10 636 940 to 13 652 368) | 19 206 671 (17 064 371 to 21 806 693) | 31 201 987 (28 557 106 to 34 245 763) |

Figure 1 presents the distribution of estimated self-harm presentations and associated hospital costs per 1000 population across local health authorities in England. As shown in the figure, the incidence of self-harm and associated hospital costs was relatively lower in the majority of coastal areas, higher in inland areas and highest in the greater London area. The estimated hospital costs by CCG in England are presented in Appendix 6.

Fig. 1.

Map of England with the estimated self-harm episodes and associated hospital cost per 1000 population in 2013.

Discussion

This study provides the first detailed estimates of self-harm presentations to hospitals and their associated hospital costs across England. The results of this study may assist national and local health decision makers in planning the distribution of funds for self-harm and prioritising interventions in areas with the highest need for tackling self-harm. Providing the incidence of self-harm presentations in each CCG by gender and age highlights sub-populations potentially where additional resources might be targeted to interventions that may prevent self-harm and assist those who have self-harmed, reducing therefore suicide deaths.

Using our incidence estimates and considering that there were 4727 (3688 male and 1039 female) deaths by suicide in England in 2013 (Statistics, 2016), our results indicate that there were 48 (24 male and 135 female) self-harm presentations to hospitals per suicide and 34 (17 male and 93 female) patients presenting with self-harm per suicide. While these ratios may seem quite large, self-harm is the strongest factor associated with subsequent suicide (Hawton et al., 2015). Risk is also particularly high in the period shortly after self-harm (Hawton et al., 2019). Therefore, primary and secondary prevention interventions that focus on reducing self-harm presentations and on provision of effective aftercare for those who do self-harm may prevent subsequent deaths by suicide (Hawton et al., 2013; Carroll et al., 2016; Geulayov et al., 2018). This is in line with economic evidence that supports the provision of public health interventions (including psychological therapies) for self-harm and suicide prevention (McDaid et al., 2017; Campion and Knapp, 2018). However, effective implementation of self-harm and suicide prevention strategies at local level is challenging in terms of both deciding what initiatives may be effective and how to evaluate these (Saunders and Smith, 2016; Hawton and Pirkis, 2017). In England, Public Health England and CCGs also have to contend with many competing health issues. Moreover, strategies need to be implemented in partnership with multiple local health service providers, as well as the local government public health services. Compliance with national guidance is another challenge for policy makers and service commissioners. Most public health and healthcare decision making in England is made at a local level, leading to substantive variation in service delivery so that many patients still do not receive psychosocial assessment when presenting at hospital for self-harm (Geulayov et al., 2016).

Our estimated incidence of self-harm presentations in England (i.e. 228 075) is close to previously reported more crude estimates of 200 000 episodes per year (Geulayov et al., 2016). This can be contrasted with much lower rates seen in Public Health England's ‘Fingertips’ database suggesting that this underestimates overall rates of self-harm by approximately 60% compared with rates based on the Multicentre Study (Clements et al., 2016). This is because Fingertips only includes self-harm episodes resulting in hospital admission based on Hospital Episodes Statistics data. It should be noted that our study has estimated only the incidence of self-harm presentations to hospitals; it is well recognised that much self-harm occurs in the community without presentation to hospital, especially among adolescents (Geulayov et al., 2018).

We estimated the hospital cost of self-harm in England in 2013 to be approximately £128.6 million (£133.8 million in 2017 prices using an inflation rate of 1.04062 based on the Hospital and Community Health Services inflation index) (Curtis and Burns, 2017). This figure is lower than the roughly estimated £161.8 million per year cost of self-harm to NHS hospitals reported recently (Tsiachristas et al., 2017). It also seemed robust after performing two sensitivity analyses that accounted for the association of self-harm rates with suicide rates (Geulayov et al., 2016) and rural areas (Harriss and Hawton, 2011). The estimated costs in the Oxford CCG area in the present study was £1 565 464 and the total hospital cost of self-harm presentations to the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford was actually £1 280 394. These figures therefore provide us with confidence about the internal validity of our cost estimates considering that the difference is likely to be due to the costs of self-harm presentations to the Horton General Hospital, a much smaller hospital than the John Radcliffe, which is also contracted by the Oxfordshire CCG. An additional reassurance for the robustness of our estimated incidence and costs is that the five hospitals included in the Multicentre Study cover populations with a wide range of socio-economic deprivation e.g. 5 in Manchester, 55 in Derby and 166 in Oxford (IMD score range: 1 most deprived to 209 most affluent) (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015). This variation is reassuring considering that socio-economic deprivation is associated with self-harm and suicide (Hawton et al., 2001).

While detailed estimates of the costs of all cases of self-harm have been made for a single hospital (Tsiachristas et al., 2017), this study is to our knowledge the only detailed analysis, applying a consistent methodology to estimate national self-harm costs by documenting care trajectories and measuring actual resource utilisation for all self-harm treatment costs, broken down by age, gender and means of self-harm, across multiple general hospital sites in different areas of England. A recent evaluation of the extension of hours of a liaison psychiatry service in a hospital in the south-west of England reported mean costs per emergency department self-harm attendance, including liaison psychiatry service use and inpatient care were reduced from £784 to £700 (£777−£694 in 2013/14 prices), but unlike our analysis NHS reference costs rather than a detailed resource and costing exercise were used to estimate costs (Opmeer et al., 2017). No attempt was made to estimate costs at a wider geographical level.

Other UK studies have concentrated on the costs of deliberate self-poisoning alone. In 2006/07 one-year costs, not including psychosocial assessment, of 1598 deliberate self-poisonings (aged >16 years) presenting to a general hospital in Nottingham were estimated using NHS reference costs to be £1.64 million or £1026 per poisoning; the authors noted that if repeated across England costs per annum would be much higher than our estimate for all self-harm costs at approximately £170 million (£192 million at 2013/14 prices) (Prescott et al., 2009). UK-wide costs for emergency department presenting paracetamol poisonings following the impact of a change in national guidelines on presentations at three hospitals in Edinburgh, Newcastle and London were estimated to be £48.3 million (£49.7 at 2013/14 prices), again using English NHS tariffs rather than measuring costs (Bateman et al., 2014). Some much older English studies also compared the costs of treating self-poisoning, including psychosocial assessment, across multiple general hospitals over periods of up to five months in the late 1990s; they highlighted substantive variations in costs in part due to type of poisoning as well as differences in care pathways (Kapur et al., 1999a, 1999b, 2002), estimating England wide costs of £56 million (£90 million at 2013/14 prices) (Kapur et al., 2003).

Information making use of the total costs of hospital presenting self-harm to estimate national costs in other high-income countries has also been limited, although access to administrative datasets linked to health insurance records in some countries potentially would allow for more detailed estimates to be produced. Data from the 2006 US Nationwide Emergency Data Sample was used to identify presentations by individuals aged 65 years and over to emergency departments, as well as hospitalisations and hospital charges (Carter and Reymann, 2014). This resulted in an estimate of almost 22 500 presentations per annum nationwide with total charges of $354 million. Other US studies have also estimated the costs of self-harm for specific population groups or for specific types of self-harm at state or national levels make use of various administrative/billing datasets. None looked at costs for all intentional self-harm (White et al., 2013; Ballard et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2017). Similarly, in Australia, cost estimates have only been made for young people, with costs between 2002 and 2012 for all children aged ⩽16 years identified through the National Hospital Morbidity Database as being hospitalised for intentional self-harm estimated to be $A 64 million (£34.5 million in 2013/14 prices). In this case neither annual costs nor detailed data for different injuries were reported (Mitchell et al., 2018). In Japan standard healthcare tariffs were combined with nationwide acute hospital discharge data to estimate costs of 7.7 billion Yen (£39.8 million in 2013/24 prices) for all drug-poisonings in people aged over 12 years in 2008 (Okumura et al., 2012). This estimate did not distinguish between intentional and unintentional poisonings, nor did it include costs for patients who were not hospitalised. An in-depth analysis of costs for all patients presenting with intentional self-harm at two hospitals in Basel, Switzerland in 2003 generated mean cost of CHF 19 165; the authors also assumed nationwide costs of CHF 191 million (£112 million in 2013/24 prices), using a national conservative estimate of 10 000 hospital presenting self-harm events per annum, but noting the very limited information on self-harm rates in the country (Czernin et al., 2012).

The strengths of this study include the precision of identification of self-harm presentations to general hospitals through the Multicentre Study, the use of hospital cost data for all episodes in Oxford and Derby, the advanced analytical approach to extrapolate self-harm incidence and hospital costs from the Multicentre Study to England, and the extensive sensitivity analyses to address the uncertainty in the results. The main study limitations are related to the available data and include: (a) the lack of hospital cost data in Manchester, (b) cost data being limited only to care received in general hospitals, which is only a part of the overall long-term costs of self-harm (Sinclair et al., 2011b) and (c) that estimated self-harm incidence and hospital cost may have changed since 2013 due to changes in the incidence patterns (e.g. increase in incidence among young females) and services provision (e.g. there has recently been a considerable increase in provision of hospital services for self-harm patients on a 24 h seven day a week basis in England).

Our analysis can help to identify specific population groups to support within localities and also draw more attention directly to self-harm when developing local suicide and self-harm prevention and reduction strategies. A key element of our approach has been to measure resource use and costs rather than simply use published health system charges, which usually do not reflect actual costs. This will also help in more accurate evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of any interventions that may reduce self-harm events.

There is certainly a need to build on recent albeit relatively small-sized economic evaluations of actions to increase the use of psychosocial assessments (Opmeer et al., 2017) to help improve referral to appropriate care pathways, as well as economic evaluations of psychological and other follow-up care (O'Connor et al., 2017; Haga et al., 2018; Park et al., 2018). The potential economic benefits of effective interventions may also be greater than shown in these analyses, as there will be additional costs to the health sector, local government and other public agencies which may be averted by any reduction in future risk of both non-fatal and fatal self-harm events (Hawton et al., 2015). Although our analysis has focused on England we believe our approach could also in principle be adapted for use in the development of self-harm prevention strategies in other country contexts, particularly those where national administrative datasets that record hospital presenting self-harm are not available.

Data

Due to constraints on the data sharing permissions of the data in the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England, we are not allowed to share the data for public use.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NIHR Oxford-Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care, and in particular Professor Belinda Lennox, for their support. Our special thanks to A-La Park at the London School of Economics and Political Science for contributing to the literature review. We also thank members of the finance departments of Oxford University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust and the University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust, for providing data and advice. The authors from Derby would also like to thank Callum Burgess, Information Analyst, University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust, as well as Abigail Marron and Anita Patel (Research Assistants at Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust). KH was supported by Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. AT acknowledges financial support by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Oxford and Thames Valley. KH is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator (Emeritus). The Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Appendix 1

Variation in patient characteristics and clinical care by method of self-harm in the three study sites

| Variable | Oxford | Manchester | Derby | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-poisoning alone | Self-injury alone | Both self-poisoning and self-injury | Self-poisoning alone | Self-injury alone | Both self-poisoning and self-injury | Self-poisoning alone | Self-injury alone | Both self-poisoning and self-injury | |

| Age (years) | * | *** | * | * | *** | * | * | *** | * |

| <18 | 147 (13) | 33 (8) | 28 (25) | 259 (10) | 204 (16) | 33 (14) | 202 (12) | 89 (21) | 17 (17) |

| 18–19 | 64 (5) | 24 (6) | 7 (6) | 135 (5) | 79 (6) | 21 (9) | 107 (6) | 43 (10) | 7 (7) |

| 20–29 | 348 (30) | 167 (42) | 32 (28) | 750 (29) | 4459 (36) | 76 (32) | 459 (27) | 122 (28) | 43 (42) |

| 30–39 | 190 (16) | 60 (15) | 23 (20) | 542 (21) | 246 (36) | 46 (19) | 303 (18) | 56 (13) | 14 (14) |

| 40–49 | 236 (20) | 51 (13) | 11 (10) | 531 (21) | 176 (14) | 44 (18) | 362 (22) | 80 (18) | 9 (9) |

| 50–59 | 106 (9) | 43 (11) | 9 (8) | 247 (10) | 75 (6) | 16 (7) | 158 (9) | 28 (6) | 7 (7) |

| 60–69 | 42 (4) | 11 (3) | 2 (2) | 68 (3) | 12 (1) | 1 (0) | 52 (3) | 10 (2) | 4 (4) |

| 70 and older | 21 (2) | 6 (2) | 2 (2) | 37 (1) | 13 (1) | 2 (1) | 30 (2) | 5 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Missing | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sex | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |||

| Male | 422 (37) | 126 (32) | 32 (28) | 1095 (43) | 575 (45) | 85 (36) | 625 (37) | 159 (37) | 41 (40) |

| Female | 733 (63) | 269 (68) | 82 (72) | 1478 (57) | 691 (55) | 154 (64) | 1048 (63) | 274 (63) | 61 (60) |

| Received psychosocial assessment | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |||

| No | 225 (19) | 197 (50) | 21 (18) | 1232 (48) | 720 (57) | 74 (31) | 515 (31) | 182 (42) | 35 (33) |

| Yes | 930 (81) | 198 (50) | 93 (82) | 1341 (52) | 546 (43) | 165 (69) | 1157 (69) | 250 (58) | 68 (67) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Admitted to hospital | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| No | 140 (12) | 202 (51) | 18 (16) | 1171 (46) | 1036 (82) | 145 (61) | 599 (36) | 280 (65) | 42 (41) |

| Yes | 1011 (88) | 193 (49) | 96 (84) | 1262 (49) | 139 (11) | 88 (37) | 1015 (61) | 139 (32) | 57 (56) |

| Missing | 4 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 140 (5) | 91 (7) | 6 (2) | 59 (3) | 14 (3) | 3 (3) |

*p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.0001; # other methods include: drowning, gunshot, gas, head banging.

Appendix 2

Variation in patient characteristics of those who received psychosocial assessment by site

| Variable | Oxford | Manchester | Derby |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (% of 894) | n (% of 1647) | n (% of 1087) | |

| Age (years)*** | |||

| <18 | 143 (16) | 128 (8) | 197 (18) |

| 18–19 | 65 (7) | 116 (7) | 70 (6) |

| 20–29 | 235 (26) | 556 (34) | 260 (24) |

| 30–39 | 141 (16) | 342 (21) | 193 (18) |

| 40–49 | 154 (17) | 294 (18) | 206 (19) |

| 50–59 | 92 (10) | 149 (9) | 95 (9) |

| 60–69 | 38 (4) | 36 (2) | 42 (4) |

| 70 and older | 26 (2) | 26 (2) | 24 (2) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sex*** | |||

| Male | 346 (39) | 727 (44) | 406 (37) |

| Female | 548 (61) | 920 (56) | 681 (63) |

| Occupational status*** | |||

| Unemployed/household | 219 (24) | 774 (47) | 367 (34) |

| Employed | 288 (32) | 407 (25) | 254 (23) |

| Disabled/retired | 152 (17) | 76 (5) | 51 (5) |

| Student | 188 (21) | 268 (16) | 227 (21) |

| Missing | 47 (5) | 122 (7) | 188 (17) |

| Ethnicity*** | |||

| White | 789 (88) | 1398 (85) | 830 (77) |

| Black | 14 (2) | 42 (3) | 10 (1) |

| Asian | 28 (3) | 80 (5) | 22 (2) |

| Other | 44 (5) | 97 (6) | 35 (3) |

| Missing | 19 (2) | 30 (2) | 190 (17) |

| Number of self-harm repetitions | |||

| 0 | 748 (84) | 1460 (83) | 943 (82) |

| 1 | 95 (11) | 186 (10) | 134 (11) |

| 2 | 23 (2) | 51 (3) | 52 (4) |

| >2 | 28 (3) | 67 (4) | 40 (3) |

| Mean (s.d.) min−max n | Mean (s.d.) min−max n | Mean (s.d.) min−max n | |

| Age | 34 (16) 12–97 894 | 33 (14) 8–931 647 | 33 (16) 10–931 087 |

| IMDS*** | 16 (11) 1–59 838 | 40 (19) 2–801 574 | 26 (16) 1–661 036 |

| Number of repetitions | 0.33 (1.18) 0–19 894 | 0.36 (1.22) 0–181 647 | 0.36 (1.07) 0–171 087 |

*p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.0001.

Appendix 3

Variation in the provision of clinical care between the three study sites

| Variable | Self-harm method | Self-harm method | Self-injury method | Self-injury method | Self-poisoning method | Self-poisoning method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Dependent: Assessed | Dependent: Admitted | Dependent: Assessed | Dependent: Admitted | Dependent: Assessed | Dependent: Admitted | |

| OR (s.e.) p-value [95% CI] | OR (s.e.) p-value [95% CI] | OR (s.e.) p-value [95% CI] | OR (s.e.) p-value [95% CI] | OR (s.e.) p-value [95% CI] | OR (s.e.) p-value [95% CI] | |

| Site (ref: Oxford) | ||||||

| Manchester | 0.48 (0.05) <0.001 [0.39;0.59] | 0.15 (0.02) <0.001 [0.12;0.19] | 0.80 (0.15) 0.231 [0.55;1.16] | 0.12 (0.03) <0.001 [0.08;0.19] | 0.35 (0.05) <0.001 [0.26;0.46] | 0.14 (0.02) <0.001 [0.10;0.20] |

| Derby | 0.81 (0.08) 0.043 [0.66;0.99] | 0.25 (0.03) <0.001 [0.20;0.31] | 1.05 (0.20) 0.791 [0.72;1.53] | 0.40 (0.08) <0.001 [0.27;0.58] | 0.67 (0.09) 0.003 [0.52;0.87] | 0.21 (0.03) <0.001 [0.15;0.28] |

| Age (years)*** | 1.01 (0.00) 0.005 [1.00;1.01] | 1.00 (0.00) 0.559 [1.00;1.01] | 1.01 (0.01) 0.040 [1.00;1.02] | 1.00 (0.01) 0.366 [1.00;1.01] | 1.00 (0.00) 0.156 [1.00;1.01] | 1.00 (0.00) 0.700 [1.00;1.01] |

| Female (ref: Male) | 0.96 (0.07) 0.588 [0.84;1.10] | 1.25 (0.09) 0.002 [1.09;1.43] | 0.65 (0.08) <0.001 [0.51;0.83] | 1.42 (0.2) 0.012 [1.08;1.86] | 1.10 (0.10) 0.282 [0.92;1.32] | 1.19 (0.11) 0.069 [0.99;1.42] |

| IMDS | 1.00 (0.00) 0.429 [0.99;1.00] | 0.99 (0.00) <0.001 [0.99;0.99] | 1.00 (0.00) 0.718 [0.99;1.01] | 0.99 (0.00) 0.007 [0.98;0.99] | 1.00 (0.00) 0.549 [0.99;1.00] | 0.99 (0.00) <0.001 [0.98;0.99] |

| Number of self-harm repetitions | 0.92 (0.02) 0.002 [0.87;0.97] | 1.00 (0.02) 0.858 [0.95;1.04] | 0.88 (0.04) 0.001 [0.81;0.95] | 0.96 (0.03) 0.194 [0.91;1.02] | 0.94 (0.02) 0.008 [0.90;0.98] | 0.99 (0.02) 0.588 [0.95;1.03] |

| Admitted to hospital (ref: Not-admitted) | 2.97 (0.23) <0.001 [2.56;3.45] | 4.16 (0.64) <0.001 [3.07;5.63] | 2.44 (0.25) <0.001 [2.00;2.98] | |||

| Received assessment (ref: Not assessed) | 2.93 (0.22) <0.001 [2.53;3.39] | 3.96 (0.61) <0.001 [2.93;5.35] | 2.51 (0.26) <0.001 [2.06;3.07] | |||

| Self-harm method (ref: Self-poisoning) | ||||||

| Self-injury | 0.79 (0.06) 0.003 [0.68;0.92] | 0.13 (0.01) <0.001 [0.11;0.16] | ||||

| Both self-injury/poisoning | 1.82 (0.27) <0.001 [1.36;2.42] | 0.58 (0.08) <0.001 [0.44;0.77] | ||||

| Self-injury method (ref: cut/stab) | ||||||

| Jump from height | 1.32 (0.56) 0.517 [0.57;3.03] | 1.74 (0.76) 0.206 [0.74;4.08] | ||||

| Hanging/asphyxiation | 1.42 (0.28) 0.073 [0.97;2.08] | 1.19 (0.24) 0.403 [0.79;1.77] | ||||

| Traffic related | 1.67 (0.70) 0.218 [0.74;3.80] | 2.03 (0.88) 0.102 [0.87;4.72] | ||||

| Other method | 0.43 (0.07) <0.001 [0.31;0.59] | 1.90 (0.33) <0.001 [1.35;2.68] | ||||

| Self-poisoning method (ref: Paracetamol) | ||||||

| Paracetamol compound | 1.20 (0.24) 0.377 [0.80;1.78] | 0.81 (0.17) 0.311 [0.54;1.21] | ||||

| Antidepressants | 1.08 (0.17) 0.618 [0.79;1.47] | 0.76 (0.12) 0.081 [0.56;1.03] | ||||

| Benzodiazepines | 0.46 (0.10) <0.001 [0.31;0.70] | 0.43 (1.00) <0.001 [0.28;0.67] | ||||

| Major tranquilisers | 0.80 (0.19) 0.356 [0.49;1.29] | 0.73 (0.20) 0.255 [0.42;1.25] | ||||

| Other | 0.78 (0.09) 0.035 [0.62;0.98] | 0.53 (0.07) <0.001 [0.42;0.67] | ||||

| Multiple drug groups | 1.10 (0.16) 0.488 [0.83;1.46] | 1.29 (0.19) 0.088 [0.96;1.72] | ||||

| Constant | 1.66 (0.24) <0.001 [1.25;2.21] | 4.64 (0.70) <0.001 [3.46;6.23] | 1.16 (0.29) 0.534 [0.72;1.87] | 0.52 (0.13) 0.011 [0.31;0.86] | 2.47 (0.50) <0.001 [1.67;3.67] | 7.26 (1.61) <0.001 [4.70;11.22] |

| Variance | 1.01 (0.20) [0.69;1.49] | 1.00 (0.19) [0.69;1.45] | 1.13 (0.34) [0.63;2.03] | 1.20 (0.55) [0.48;2.97] | 0.93 (0.31) [0.49;1.78] | 1.14 (0.29) [0.69;1.88] |

| Sample size | 7180 episodes 5241 patients |

7180 episodes 5241 patients |

2281 episodes 1696 patients |

2281episodes 1696 patients |

3947 episodes 3143 patients |

3947 episodes 3143 patients |

Ref: Reference category.

Appendix 4.

Self-harm incidence per 1000 population in the three study sites

Appendix 5

Market force factors (2013/14)

| Variable | MFF | MFF indexed to Oxford |

|---|---|---|

| Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust | 1. 100 325 | 1.00 |

| Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 1. 056 801 | 0. 960 444 |

| Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 1. 033 263 | 0. 939 053 |

Appendix 6.

Hospital cost of self-harm by local authority across England in 2013

| Main male costs | Main female costs | Main total costs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Lower 95% CI | Higher 95% CI | Mean | Lower 95% CI | Higher 95% CI | Mean | Lower 95% CI | Higher 95% CI | |

| England | 49 559 150 | 43 896 127 | 56 429 207 | 79 046 705 | 70 310 153 | 89 561 701 | 128 605 855 | 117 835 026 | 140 934 979 |

| North of England | 13 887 113 | 12 303 350 | 15 805 226 | 22 301 908 | 19 843 575 | 25 260 926 | 36 189 021 | 33 162 982 | 39 653 206 |

| Cheshire, Warrington and Wirral | 1 100 384 | 973 900 | 1 253 603 | 1 771 073 | 1 576 101 | 2 005 890 | 2 871 457 | 2 630 219 | 3 148 052 |

| NHS Eastern Cheshire | 172 581 | 152 590 | 196 709 | 271 350 | 241 508 | 307 445 | 443 932 | 406 756 | 486 552 |

| NHS South Cheshire | 161 163 | 142 624 | 183 631 | 257 369 | 229 161 | 291 325 | 418 531 | 383 522 | 458 563 |

| NHS Vale Royal | 92 285 | 81 705 | 105 095 | 148 347 | 132 079 | 167 953 | 240 632 | 220 491 | 263 736 |

| NHS Warrington | 192 429 | 170 325 | 219 251 | 299 601 | 266 535 | 339 364 | 492 030 | 450 763 | 539 098 |

| NHS West Cheshire | 203 615 | 180 175 | 232 021 | 332 425 | 295 733 | 376 625 | 536 040 | 490 911 | 587 774 |

| NHS Wirral | 278 311 | 246 445 | 316 953 | 461 980 | 411 123 | 523 196 | 740 292 | 678 246 | 811 878 |

| Durham, Darlington and Tees | 1 064 860 | 943 310 | 1 212 447 | 1 728 212 | 1 537 858 | 1 956 994 | 2 793 072 | 2 559 134 | 3 060 861 |

| NHS Darlington | 94 699 | 83 856 | 107 826 | 154 630 | 137 669 | 175 018 | 249 329 | 228 506 | 273 235 |

| NHS Durham Dales, Easington and Sedgefield | 244 908 | 216 826 | 278 943 | 391 122 | 348 163 | 442 899 | 636 030 | 582 815 | 697 091 |

| NHS Hartlepool and Stockton-on-Tees | 258 760 | 229 215 | 294 618 | 420 538 | 374 078 | 476 440 | 679 298 | 622 276 | 744 621 |

| NHS North Durham | 223 425 | 197 881 | 254 400 | 359 096 | 319 339 | 406 940 | 582 521 | 533 607 | 638 487 |

| NHS South Tees | 243 068 | 215 500 | 276 445 | 402 825 | 358 575 | 456 039 | 645 893 | 592 096 | 707 901 |

| Greater Manchester | 2 559 987 | 2 268 440 | 2 913 143 | 4 093 480 | 3 640 695 | 4 635 983 | 6 653 467 | 6 097 488 | 7 289 990 |

| NHS Bolton | 256 698 | 227 604 | 292 036 | 411 165 | 365 986 | 465 501 | 667 864 | 612 242 | 731 435 |

| NHS Bury | 167 910 | 148 714 | 191 226 | 273 731 | 243 554 | 309 996 | 441 641 | 404 593 | 484 124 |

| NHS Central Manchester | 184 782 | 164 203 | 209 545 | 300 498 | 267 199 | 340 432 | 485 280 | 445 037 | 531 395 |

| NHS Heywood, Middleton and Rochdale | 192 181 | 170 357 | 218 679 | 318 467 | 283 591 | 360 325 | 510 648 | 468 257 | 559 397 |

| NHS North Manchester | 172 856 | 153 331 | 196 410 | 259 338 | 230 113 | 294 635 | 432 194 | 395 981 | 473 473 |

| NHS Oldham | 204 914 | 181 685 | 233 123 | 335 378 | 298 741 | 379 294 | 540 292 | 495 539 | 591 474 |

| NHS Salford | 227 292 | 201 398 | 258 687 | 354 552 | 315 171 | 401 869 | 581 844 | 533 189 | 637 302 |

| NHS South Manchester | 154 637 | 137 174 | 175 698 | 253 576 | 225 015 | 288 044 | 408 213 | 373 682 | 447 831 |

| NHS Stockport | 256 317 | 226 817 | 292 054 | 410 542 | 365 203 | 465 090 | 666 859 | 610 738 | 731 161 |

| NHS Tameside and Glossop | 233 695 | 206 953 | 266 160 | 374 366 | 333 101 | 424 011 | 608 061 | 557 102 | 666 259 |

| NHS Trafford | 210 633 | 186 424 | 239 972 | 337 298 | 300 054 | 382 142 | 547 931 | 501 860 | 600 655 |

| NHS Wigan Borough | 298 072 | 263 767 | 339 649 | 464 570 | 413 193 | 526 343 | 762 642 | 698 556 | 835 723 |

| Lancashire | 1 329 281 | 1 177 491 | 1 513 586 | 2 132 058 | 1 898 172 | 2 413 714 | 3 461 339 | 3 172 633 | 3 791 458 |

| NHS Blackburn with Darwen | 135 463 | 120 112 | 154 066 | 219 743 | 195 785 | 248 494 | 355 206 | 325 879 | 388 795 |

| NHS Blackpool | 128 026 | 113 283 | 145 898 | 203 922 | 181 585 | 230 764 | 331 948 | 304 208 | 363 641 |

| NHS Chorley and South Ribble | 158 216 | 139 996 | 180 284 | 243 498 | 216 614 | 275 863 | 401 715 | 368 033 | 440 153 |

| NHS East Lancashire | 336 060 | 297 641 | 382 673 | 537 924 | 478 880 | 608 929 | 873 984 | 800 958 | 957 412 |

| NHS Fylde and Wyre | 141 753 | 125 420 | 161 519 | 222 895 | 198 337 | 252 619 | 364 648 | 334 091 | 399 624 |

| NHS Greater Preston | 189 700 | 168 096 | 215 904 | 299 502 | 266 525 | 339 047 | 489 202 | 448 512 | 535 692 |

| NHS Lancashire North | 141 690 | 125 646 | 161 147 | 240 169 | 213 926 | 271 626 | 381 859 | 350 183 | 418 428 |

| NHS West Lancashire | 98 373 | 87 161 | 111 967 | 164 405 | 146 445 | 185 996 | 262 778 | 240 886 | 288 036 |

| Merseyside | 1 088 812 | 964 948 | 1 239 277 | 1 790 535 | 1 592 166 | 2 028 890 | 2 879 347 | 2 638 491 | 3 157 255 |

| NHS Halton | 113 806 | 100 814 | 129 581 | 186 149 | 165 630 | 210 812 | 299 955 | 274 785 | 328 858 |

| NHS Knowsley | 127 721 | 113 235 | 145 280 | 225 917 | 201 005 | 255 926 | 353 638 | 324 008 | 388 121 |

| NHS Liverpool | 449 910 | 399 025 | 511 673 | 734 684 | 652 985 | 832 948 | 1 184 594 | 1 085 374 | 1 298 390 |

| NHS South Sefton | 140 808 | 124 711 | 160 311 | 233 182 | 207 385 | 264 216 | 373 990 | 342 579 | 410 254 |

| NHS Southport and Formby | 96 350 | 85 276 | 109 748 | 157 140 | 139 945 | 177 957 | 253 491 | 232 255 | 277 848 |

| NHS St Helens | 160 217 | 141 828 | 182 481 | 253 463 | 225 468 | 287 148 | 413 680 | 378 966 | 453 374 |

| Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear | 1 751 267 | 1 551 092 | 1 994 416 | 2 799 883 | 2 490 451 | 3 172 076 | 4 551 150 | 4 169 294 | 4 988 632 |

| NHS Cumbria | 450 027 | 398 135 | 512 795 | 703 067 | 625 750 | 796 408 | 1 153 094 | 1 056 739 | 1 263 908 |

| NHS Gateshead | 182 704 | 161 756 | 208 136 | 290 995 | 258 607 | 329 970 | 473 699 | 433 715 | 519 459 |

| NHS Newcastle North and East | 142 672 | 126 790 | 161 783 | 230 963 | 205 376 | 261 844 | 373 634 | 342 612 | 409 237 |

| NHS Newcastle West | 132 614 | 117 620 | 150 801 | 211 904 | 188 481 | 240 073 | 344 518 | 315 853 | 377 426 |

| NHS North Tyneside | 182 521 | 161 504 | 207 982 | 294 126 | 261 336 | 333 711 | 476 647 | 436 195 | 523 085 |

| NHS Northumberland | 277 485 | 245 637 | 316 004 | 440 888 | 392 285 | 499 667 | 718 373 | 658 026 | 787 644 |

| NHS South Tyneside | 133 126 | 117 870 | 151 629 | 218 353 | 194 215 | 247 415 | 351 479 | 321 898 | 385 489 |

| NHS Sunderland | 250 117 | 221 498 | 284 868 | 409 588 | 364 273 | 464 042 | 659 706 | 604 222 | 723 529 |

| North Yorkshire and Humber | 1 518 410 | 1 344 906 | 1 728 981 | 2 382 501 | 2 120 376 | 2 698 077 | 3 900 911 | 3 574 835 | 4 273 933 |

| NHS East Riding of Yorkshire | 275 978 | 244 154 | 314 450 | 435 460 | 387 841 | 493 023 | 711 439 | 652 087 | 779 534 |

| NHS Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby | 143 665 | 127 341 | 163 487 | 202 201 | 179 996 | 229 052 | 345 865 | 317 182 | 378 567 |

| NHS Harrogate and Rural District | 143 092 | 126 721 | 162 920 | 222 174 | 197 870 | 251 554 | 365 266 | 334 919 | 400 033 |

| NHS Hull | 244 974 | 217 239 | 278 611 | 383 601 | 340 949 | 434 871 | 628 575 | 576 103 | 688 739 |

| NHS North East Lincolnshire | 143 510 | 127 135 | 163 396 | 230 678 | 205 359 | 261 131 | 374 188 | 342 943 | 409 892 |

| NHS North Lincolnshire | 152 014 | 134 526 | 173 217 | 238 770 | 212 504 | 270 395 | 390 783 | 358 078 | 428 291 |

| NHS Scarborough and Ryedale | 94 581 | 83 757 | 107 671 | 152 313 | 135 579 | 172 522 | 246 894 | 226 212 | 270 688 |

| NHS Vale of York | 320 596 | 283 995 | 364 959 | 517 305 | 460 170 | 586 076 | 837 900 | 767 693 | 918 310 |

| South Yorkshire and Bassetlaw | 1 358 698 | 1 203 808 | 1 546 792 | 2 171 202 | 1 932 085 | 2 458 357 | 3 529 900 | 3 235 238 | 3 866 250 |

| NHS Barnsley | 217 388 | 192 370 | 247 688 | 344 160 | 306 308 | 389 701 | 561 549 | 514 505 | 615 241 |

| NHS Bassetlaw | 104 426 | 92 459 | 118 927 | 162 850 | 145 060 | 184 258 | 267 275 | 245 101 | 292 731 |

| NHS Doncaster | 278 518 | 246 671 | 317 171 | 437 862 | 389 607 | 495 880 | 716 380 | 656 431 | 784 725 |

| NHS Rotherham | 234 809 | 207 888 | 267 411 | 375 268 | 334 163 | 424 642 | 610 077 | 559 139 | 668 275 |

| NHS Sheffield | 523 556 | 464 363 | 595 365 | 851 062 | 757 212 | 963 915 | 1 374 619 | 1 260 388 | 1 506 022 |

| West Yorkshire | 2 115 414 | 1 874 674 | 2 407 489 | 3 432 964 | 3 054 606 | 3 886 608 | 5 548 379 | 5 086 013 | 6 077 627 |

| NHS Airedale, Wharfedale and Craven | 137 888 | 122 120 | 156 982 | 224 126 | 199 622 | 253 643 | 362 015 | 331 783 | 396 698 |

| NHS Bradford City | 80 385 | 71 481 | 91 123 | 127 329 | 113 540 | 143 885 | 207 715 | 190 799 | 226 969 |

| NHS Bradford Districts | 298 403 | 264 564 | 339 408 | 501 110 | 446 268 | 566 848 | 799 513 | 733 169 | 876 054 |

| NHS Calderdale | 190 630 | 168 751 | 217 116 | 302 095 | 268 897 | 342 005 | 492 725 | 451 506 | 539 784 |

| NHS Greater Huddersfield | 223 233 | 197 776 | 254 084 | 352 997 | 314 075 | 399 801 | 576 230 | 528 117 | 631 291 |

| NHS Leeds North | 178 555 | 158 166 | 203 310 | 291 577 | 259 312 | 330 422 | 470 132 | 430 594 | 515 671 |

| NHS Leeds South and East | 225 209 | 199 648 | 256 194 | 361 167 | 321 097 | 409 362 | 586 377 | 537 429 | 642 572 |

| NHS Leeds West | 305 370 | 270 864 | 347 124 | 513 563 | 456 235 | 582 772 | 818 933 | 750 124 | 898 143 |

| NHS North Kirklees | 172 257 | 152 675 | 196 037 | 277 105 | 246 887 | 313 320 | 449 362 | 412 153 | 491 920 |

| NHS Wakefield | 303 484 | 268 559 | 345 786 | 481 894 | 428 741 | 545 812 | 785 377 | 719 481 | 860 634 |

| Midlands and East of England | 14 893 788 | 13 193 223 | 16 957 069 | 23 776 299 | 21 161 598 | 26 925 731 | 38 670 087 | 35 442 360 | 42 360 185 |

| Arden, Herefordshire and Worcestershire | 1 489 935 | 1 319 827 | 1 696 517 | 2 349 026 | 2 090 771 | 2 659 311 | 3 838 961 | 3 518 289 | 4 204 805 |

| NHS Coventry and Rugby | 404 080 | 358 338 | 459 590 | 641 551 | 570 792 | 726 610 | 1 045 631 | 958 664 | 1 145 219 |

| NHS Herefordshire | 165 398 | 146 396 | 188 393 | 256 183 | 228 170 | 289 966 | 421 581 | 386 607 | 461 734 |

| NHS Redditch and Bromsgrove | 162 733 | 144 099 | 185 300 | 256 586 | 228 360 | 290 559 | 419 319 | 384 242 | 459 461 |

| NHS South Warwickshire | 236 317 | 209 272 | 269 088 | 366 857 | 326 413 | 415 599 | 603 174 | 552 695 | 660 955 |

| NHS South Worcestershire | 262 876 | 232 728 | 299 424 | 420 221 | 374 159 | 475 666 | 683 097 | 625 935 | 748 492 |

| NHS Warwickshire North | 171 223 | 151 568 | 195 030 | 272 640 | 242 724 | 308 645 | 443 863 | 406 769 | 486 263 |

| NHS Wyre Forest | 87 307 | 77 305 | 99 411 | 134 989 | 120 119 | 152 916 | 222 295 | 203 755 | 243 588 |

| Birmingham and the Black Country | 2 224 063 | 1 972 205 | 2 529 454 | 3 681 025 | 3 277 631 | 4 165 569 | 5 905 087 | 5 415 984 | 6 467 345 |

| NHS Birmingham CrossCity | 651 054 | 577 746 | 739 994 | 1 111 544 | 990 100 | 1 257 375 | 1 762 598 | 1 616 624 | 1 931 103 |

| NHS Birmingham South and Central | 182 842 | 162 460 | 207 507 | 319 662 | 284 869 | 361 632 | 502 504 | 461 059 | 550 191 |

| NHS Dudley | 283 473 | 250 946 | 322 897 | 452 421 | 402 727 | 512 143 | 735 894 | 674 310 | 806 203 |

| NHS Sandwell and West Birmingham | 446 438 | 396 057 | 507 547 | 723 442 | 643 864 | 819 100 | 1 169 880 | 1 072 951 | 1 281 204 |

| NHS Solihull | 184 239 | 163 169 | 209 780 | 304 408 | 271 157 | 344 414 | 488 648 | 447 920 | 535 496 |

| NHS Walsall | 244 332 | 216 460 | 278 128 | 398 287 | 354 752 | 450 529 | 642 619 | 589 198 | 703 747 |

| NHS Wolverhampton | 231 685 | 205 339 | 263 646 | 371 260 | 330 389 | 420 255 | 602 945 | 552 704 | 660 460 |

| Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire | 1 835 022 | 1 625 453 | 2 089 118 | 2 917 232 | 2 595 875 | 3 303 920 | 4 752 254 | 4 355 355 | 5 206 655 |

| NHS Erewash | 86 958 | 76 936 | 99 112 | 140 001 | 124 520 | 158 618 | 226 959 | 207 837 | 248 830 |

| NHS Hardwick | 99 406 | 87 935 | 113 307 | 156 772 | 139 513 | 177 543 | 256 178 | 234 694 | 280 812 |

| NHS Mansfield & Ashfield | 177 237 | 156 891 | 201 892 | 282 524 | 251 348 | 320 026 | 459 761 | 421 196 | 503 898 |

| NHS Newark & Sherwood | 103 968 | 92 033 | 118 428 | 165 937 | 147 700 | 187 902 | 269 905 | 247 277 | 295 838 |

| NHS North Derbyshire | 247 234 | 218 803 | 281 626 | 385 079 | 342 791 | 436 010 | 632 313 | 579 632 | 692 846 |

| NHS Nottingham City | 303 335 | 269 307 | 344 366 | 495 577 | 440 883 | 561 555 | 798 912 | 732 599 | 874 969 |

| NHS Nottingham North & East | 133 931 | 118 505 | 152 617 | 214 685 | 190 997 | 243 199 | 348 615 | 319 314 | 382 176 |

| NHS Nottingham West | 103 122 | 91 274 | 117 483 | 158 980 | 141 312 | 180 232 | 262 102 | 240 032 | 287 321 |

| NHS Rushcliffe | 102 917 | 91 112 | 117 224 | 160 152 | 142 532 | 181 382 | 263 069 | 241 083 | 288 285 |

| NHS Southern Derbyshire | 476 914 | 422 422 | 543 050 | 757 527 | 674 257 | 857 829 | 1 234 440 | 1 131 455 | 1 352 213 |

| East Anglia | 2 219 504 | 1 965 570 | 2 527 551 | 3 477 435 | 3 094 840 | 3 937 845 | 5 696 939 | 5 220 733 | 6 241 106 |

| NHS Cambridgeshire and Peterborough | 801 904 | 710 307 | 913 134 | 1 248 444 | 1 110 422 | 1 414 439 | 2 050 348 | 1 878 999 | 2 246 112 |

| NHS Great Yarmouth & Waveney | 183 519 | 162 604 | 208 877 | 292 984 | 260 986 | 331 567 | 476 503 | 436 836 | 521 989 |

| NHS Ipswich and East Suffolk | 354 911 | 314 271 | 404 164 | 554 633 | 493 913 | 627 708 | 909 544 | 833 720 | 996 183 |

| NHS North Norfolk | 141 171 | 124 911 | 160 921 | 222 018 | 197 803 | 251 386 | 363 189 | 332 966 | 397 904 |

| NHS Norwich | 181 815 | 161 022 | 207 050 | 289 772 | 257 416 | 328 659 | 471 587 | 431 936 | 517 056 |

| NHS South Norfolk | 208 959 | 185 022 | 237 940 | 329 816 | 293 744 | 373 253 | 538 775 | 493 917 | 590 254 |

| NHS West Norfolk | 146 906 | 130 054 | 167 286 | 232 028 | 206 551 | 262 813 | 378 934 | 347 250 | 415 335 |

| NHS West Suffolk | 200 319 | 177 393 | 228 160 | 307 742 | 273 836 | 348 581 | 508 061 | 465 588 | 556 507 |

| Essex | 1 578 815 | 1 397 893 | 1 798 085 | 2 535 814 | 2 257 034 | 2 871 270 | 4 114 629 | 3 770 424 | 4 508 926 |

| NHS Basildon and Brentwood | 227 666 | 201 625 | 259 288 | 374 933 | 333 804 | 424 375 | 602 599 | 552 190 | 660 569 |

| NHS Castle Point, Rayleigh and Rochford | 152 855 | 135 372 | 174 013 | 243 408 | 216 862 | 275 357 | 396 264 | 363 282 | 434 073 |

| NHS Mid Essex | 347 187 | 307 296 | 395 532 | 548 006 | 487 563 | 620 727 | 895 193 | 820 081 | 981 123 |

| NHS North East Essex | 276 493 | 244 990 | 314 752 | 445 619 | 396 714 | 504 454 | 722 111 | 661 810 | 791 165 |

| NHS Southend | 160 127 | 141 703 | 182 478 | 254 057 | 226 099 | 287 680 | 414 183 | 379 419 | 453 833 |

| NHS Thurrock | 151 221 | 133 947 | 172 181 | 240 642 | 214 062 | 272 493 | 391 864 | 359 088 | 429 288 |

| NHS West Essex | 263 267 | 233 042 | 299 847 | 429 149 | 381 800 | 486 133 | 692 415 | 634 255 | 759 242 |

| Hertfordshire and the South Midlands | 2 500 191 | 2 213 730 | 2 846 869 | 3 995 713 | 3 554 400 | 4 527 149 | 6 495 903 | 5 951 194 | 7 118 271 |

| NHS Bedfordshire | 393 422 | 348 417 | 448 032 | 622 182 | 553 398 | 704 958 | 1 015 604 | 930 396 | 1 113 103 |

| NHS Corby | 59 253 | 52 435 | 67 525 | 96 412 | 85 769 | 109 200 | 155 665 | 142 600 | 170 602 |

| NHS East and North Hertfordshire | 503 813 | 446 045 | 573 763 | 816 786 | 726 616 | 925 404 | 1 320 599 | 1 209 726 | 1 447 561 |

| NHS Herts Valleys | 527 262 | 466 807 | 600 607 | 850 272 | 756 251 | 963 342 | 1 377 534 | 1 261 655 | 1 510 014 |

| NHS Luton | 195 984 | 173 796 | 222 848 | 312 750 | 278 377 | 354 024 | 508 734 | 466 576 | 557 055 |

| NHS Milton Keynes | 244 520 | 216 508 | 278 505 | 387 091 | 344 082 | 438 797 | 631 610 | 578 568 | 692 261 |

| NHS Nene | 575 936 | 509 846 | 656 078 | 910 220 | 809 914 | 1 030 835 | 1 486 157 | 1 361 511 | 1 628 381 |

| Leicestershire and Lincolnshire | 1 585 588 | 1 404 791 | 1 805 136 | 2 562 022 | 2 280 612 | 2 900 942 | 4 147 610 | 3 801 209 | 4 543 664 |

| NHS East Leicestershire and Rutland | 291 755 | 258 306 | 332 289 | 463 068 | 412 466 | 523 957 | 754 823 | 691 914 | 826 810 |

| NHS Leicester City | 311 154 | 276 222 | 353 455 | 521 697 | 464 087 | 591 221 | 832 851 | 763 545 | 912 544 |

| NHS Lincolnshire East | 193 449 | 171 224 | 220 364 | 310 939 | 276 875 | 352 113 | 504 387 | 462 190 | 552 840 |

| NHS Lincolnshire West | 206 466 | 182 889 | 235 061 | 342 728 | 304 994 | 388 003 | 549 194 | 503 347 | 602 002 |

| NHS South Lincolnshire | 124 787 | 110 432 | 142 157 | 202 174 | 179 963 | 228 909 | 326 962 | 299 549 | 358 507 |

| NHS South West Lincolnshire | 108 196 | 95 757 | 123 248 | 175 734 | 156 502 | 198 900 | 283 931 | 260 179 | 311 239 |

| NHS West Leicestershire | 349 781 | 309 847 | 398 278 | 545 681 | 485 573 | 617 895 | 895 462 | 820 684 | 980 694 |

| Shropshire and Staffordshire | 1 460 671 | 1 293 388 | 1 663 534 | 2 258 032 | 2 010 121 | 2 556 347 | 3 718 703 | 3 408 414 | 4 072 923 |

| NHS Cannock Chase | 125 012 | 110 652 | 142 422 | 196 115 | 174 599 | 222 012 | 321 127 | 294 289 | 351 751 |

| NHS East Staffordshire | 115 163 | 101 892 | 131 247 | 178 517 | 158 925 | 202 090 | 293 680 | 269 128 | 321 661 |

| NHS North Staffordshire | 196 300 | 173 825 | 223 539 | 306 331 | 272 648 | 346 893 | 502 631 | 460 636 | 550 692 |

| NHS Shropshire | 280 082 | 248 022 | 318 938 | 427 111 | 380 527 | 483 206 | 707 193 | 648 694 | 774 120 |

| NHS South East Staffs and Seisdon and Peninsular | 206 793 | 183 116 | 235 491 | 316 894 | 282 026 | 358 942 | 523 688 | 480 120 | 573 631 |

| NHS Stafford and Surrounds | 140 425 | 124 284 | 159 993 | 209 912 | 186 787 | 237 751 | 350 337 | 321 122 | 383 651 |

| NHS Stoke on Trent | 239 651 | 212 324 | 272 858 | 373 679 | 332 302 | 423 258 | 613 331 | 562 053 | 671 780 |

| NHS Telford & Wrekin | 157 245 | 139 290 | 179 042 | 249 472 | 222 211 | 282 262 | 406 717 | 372 937 | 445 263 |

| London | 8 189 719 | 7 251 950 | 9 326 903 | 12 933 335 | 11 470 902 | 14 688 055 | 21 123 054 | 19 331 828 | 23 179 317 |

| London | 8 189 719 | 7 251 950 | 9 326 903 | 12 933 335 | 11 470 902 | 14 688 055 | 21 123 054 | 19 331 828 | 23 179 317 |

| NHS Barking & Dagenham | 173 890 | 154 258 | 197 695 | 297 786 | 264 919 | 337 293 | 471 676 | 432 282 | 517 087 |

| NHS Barnet | 341 981 | 303 010 | 389 260 | 555 678 | 493 426 | 630 328 | 897 659 | 821 917 | 984 728 |

| NHS Camden | 230 162 | 203 662 | 262 233 | 358 813 | 317 687 | 408 428 | 588 976 | 538 562 | 646 710 |

| NHS City and Hackney | 266 555 | 235 822 | 303 584 | 425 072 | 376 402 | 483 811 | 691 626 | 632 410 | 759 564 |

| NHS Enfield | 292 814 | 259 614 | 333 053 | 495 297 | 440 394 | 561 107 | 788 112 | 722 072 | 864 441 |

| NHS Haringey | 268 651 | 237 816 | 305 966 | 412 802 | 366 034 | 468 943 | 681 453 | 623 646 | 747 486 |

| NHS Havering | 214 486 | 190 025 | 244 157 | 360 729 | 320 964 | 408 608 | 575 214 | 526 990 | 630 875 |

| NHS Islington | 224 579 | 198 718 | 255 754 | 351 822 | 311 234 | 400 879 | 576 401 | 526 870 | 633 334 |

| NHS Newham | 332 204 | 294 544 | 377 499 | 489 373 | 434 831 | 555 082 | 821 578 | 753 195 | 898 832 |

| NHS Redbridge | 267 233 | 236 959 | 303 903 | 437 770 | 389 132 | 496 139 | 705 004 | 645 990 | 772 909 |

| NHS Tower Hamlets | 289 871 | 256 840 | 329 646 | 429 186 | 379 859 | 488 622 | 719 057 | 657 743 | 788 519 |

| NHS Waltham Forest | 260 817 | 230 918 | 297 068 | 405 311 | 359 669 | 460 126 | 666 127 | 609 818 | 730 619 |

| NHS Brent | 313 060 | 277 263 | 356 396 | 480 095 | 426 093 | 544 956 | 793 155 | 726 250 | 869 454 |

| NHS Central London (Westminster) | 174 925 | 154 589 | 199 571 | 234 303 | 207 062 | 267 021 | 409 228 | 374 011 | 449 398 |

| NHS Ealing | 337 899 | 299 234 | 384 736 | 514 574 | 456 471 | 584 157 | 852 473 | 780 348 | 934 530 |

| NHS Hammersmith and Fulham | 179 844 | 159 031 | 205 055 | 284 328 | 251 225 | 324 011 | 464 172 | 423 932 | 510 423 |

| NHS Harrow | 228 220 | 202 285 | 259 665 | 359 147 | 319 090 | 407 332 | 587 366 | 538 070 | 643 736 |

| NHS Hillingdon | 271 188 | 240 428 | 308 464 | 433 577 | 385 514 | 491 345 | 704 765 | 645 877 | 772 393 |

| NHS Hounslow | 258 975 | 229 308 | 294 950 | 390 177 | 345 967 | 443 163 | 649 152 | 594 155 | 711 611 |

| NHS West London (Kensington and Chelsea, Queen's Park and Paddington) | 220 849 | 195 106 | 252 046 | 329 807 | 291 522 | 375 857 | 550 656 | 502 850 | 605 176 |

| NHS Bexley | 211 470 | 187 396 | 240 654 | 360 589 | 321 003 | 408 203 | 572 059 | 524 334 | 627 341 |

| NHS Bromley | 286 908 | 253 876 | 326 894 | 471 262 | 418 810 | 534 356 | 758 170 | 694 010 | 832 030 |

| NHS Croydon | 342 400 | 303 309 | 389 722 | 575 146 | 511 199 | 651 823 | 917 546 | 840 445 | 1 006 788 |

| NHS Greenwich | 256 775 | 227 480 | 292 287 | 403 316 | 358 057 | 457 738 | 660 091 | 604 425 | 723 859 |

| NHS Kingston | 159 445 | 141 158 | 181 617 | 257 810 | 228 929 | 292 458 | 417 255 | 382 032 | 457 634 |

| NHS Lambeth | 330 260 | 292 166 | 376 244 | 502 233 | 444 079 | 572 467 | 832 493 | 760 872 | 914 475 |

| NHS Lewisham | 281 815 | 249 384 | 321 128 | 451 728 | 400 344 | 513 363 | 733 543 | 670 891 | 805 451 |

| NHS Merton | 196 759 | 174 007 | 224 337 | 305 596 | 270 687 | 347 524 | 502 355 | 459 338 | 551 500 |

| NHS Richmond | 179 182 | 158 254 | 204 506 | 280 691 | 248 935 | 318 936 | 459 873 | 420 434 | 504 991 |

| NHS Southwark | 307 075 | 271 729 | 349 839 | 481 747 | 426 266 | 548 729 | 788 823 | 721 106 | 866 484 |

| NHS Sutton | 182 502 | 161 527 | 207 912 | 297 606 | 264 579 | 337 379 | 480 108 | 439 537 | 526 584 |

| NHS Wandsworth | 306 924 | 271 250 | 350 056 | 499 964 | 441 146 | 570 668 | 806 888 | 736 075 | 888 466 |

| South of England | 12 588 530 | 11 149 072 | 14 336 034 | 20 035 163 | 17 831 861 | 22 684 533 | 32 623 693 | 29 894 968 | 35 745 008 |

| Bath, Gloucestershire, Swindon and Wiltshire | 1 360 008 | 1 203 931 | 1 549 215 | 2 150 670 | 1 914 702 | 2 434 443 | 3 510 678 | 3 217 431 | 3 845 762 |

| NHS Bath and North East Somerset | 164 642 | 145 972 | 187 301 | 272 004 | 242 247 | 307 740 | 436 647 | 400 513 | 478 202 |

| NHS Gloucestershire | 548 929 | 485 844 | 625 379 | 870 630 | 775 014 | 985 740 | 1 419 559 | 1 300 750 | 1 555 505 |

| NHS Swindon | 211 307 | 186 904 | 240 875 | 323 624 | 287 643 | 366 946 | 534 931 | 489 904 | 586 316 |

| NHS Wiltshire | 435 130 | 385 230 | 495 623 | 684 412 | 609 675 | 774 396 | 1 119 542 | 1 026 294 | 1 226 136 |

| Bristol, North Somerset, Somerset and South Gloucestershire | 1 321 077 | 1 170 431 | 1 503 635 | 2 096 805 | 1 865 374 | 2 375 688 | 3 417 882 | 3 132 206 | 3 745 003 |

| NHS Bristol | 421 650 | 373 871 | 479 597 | 663 885 | 589 406 | 753 729 | 1 085 535 | 994 433 | 1 190 032 |

| NHS North Somerset | 179 247 | 158 536 | 204 268 | 285 417 | 254 011 | 323 269 | 464 664 | 425 665 | 509 509 |

| NHS Somerset | 469 255 | 415 721 | 534 081 | 754 206 | 671 953 | 853 247 | 1 223 461 | 1 121 569 | 1 340 429 |

| NHS South Gloucestershire | 250 925 | 222 211 | 285 785 | 393 297 | 349 932 | 445 432 | 644 222 | 590 296 | 705 667 |

| Devon, Cornwall and Isles of Scilly | 1 470 888 | 1 302 697 | 1 674 709 | 2 370 677 | 2 110 650 | 2 684 156 | 3 841 566 | 3 520 033 | 4 210 404 |

| NHS Kernow | 466 117 | 412 720 | 530 731 | 759 014 | 675 959 | 859 112 | 1 225 131 | 1 122 724 | 1 342 896 |

| NHS North, East, West Devon | 771 619 | 683 596 | 878 533 | 1 238 119 | 1 102 074 | 1 401 742 | 2 009 738 | 1 841 884 | 2 202 026 |

| NHS South Devon and Torbay | 233 153 | 206 394 | 265 492 | 373 544 | 332 629 | 423 056 | 606 697 | 555 953 | 664 822 |

| Kent and Medway | 1 591 149 | 1 409 819 | 1 811 315 | 2 586 491 | 2 304 462 | 2 926 195 | 4 177 640 | 3 830 305 | 4 574 720 |

| NHS Ashford | 107 836 | 95 481 | 122 794 | 179 246 | 159 780 | 202 641 | 287 082 | 263 216 | 314 452 |

| NHS Canterbury and Coastal | 177 364 | 157 455 | 201 545 | 306 759 | 273 537 | 346 677 | 484 123 | 444 269 | 530 211 |

| NHS Dartford, Gravesham and Swanley | 231 298 | 204 860 | 263 330 | 371 832 | 330 866 | 421 112 | 603 130 | 552 651 | 660 792 |

| NHS Medway | 254 346 | 225 467 | 289 353 | 408 427 | 363 552 | 462 226 | 662 773 | 607 699 | 725 852 |

| NHS South Kent Coast | 181 252 | 160 530 | 206 371 | 283 859 | 252 958 | 321 039 | 465 111 | 426 536 | 509 315 |

| NHS Swale | 99 795 | 88 456 | 113 557 | 159 298 | 141 932 | 180 164 | 259 093 | 237 608 | 283 669 |

| NHS Thanet | 114 822 | 101 809 | 130 615 | 194 529 | 173 435 | 219 905 | 309 351 | 283 763 | 338 907 |

| NHS West Kent | 424 436 | 375 633 | 483 551 | 682 542 | 608 201 | 772 060 | 1 106 978 | 1 014 666 | 1 212 442 |

| Surrey and Sussex | 2 458 957 | 2 176 289 | 2 801 288 | 3 910 345 | 3 478 458 | 4 429 834 | 6 369 302 | 5 834 245 | 6 981 445 |

| NHS Brighton & Hove | 281 322 | 249 177 | 320 314 | 435 142 | 386 287 | 493 932 | 716 464 | 656 097 | 785 481 |

| NHS Coastal West Sussex | 405 677 | 358 967 | 462 182 | 653 552 | 581 643 | 740 738 | 1 059 229 | 970 117 | 1 161 531 |

| NHS Crawley | 103 638 | 91 725 | 118 069 | 160 826 | 142 703 | 182 608 | 264 463 | 242 060 | 290 006 |

| NHS East Surrey | 162 273 | 143 589 | 184 881 | 260 186 | 231 542 | 294 662 | 422 459 | 386 965 | 463 023 |

| NHS Eastbourne, Hailsham and Seaford | 151 984 | 134 592 | 173 030 | 250 615 | 223 223 | 283 676 | 402 599 | 369 000 | 441 303 |

| NHS Guildford and Waverley | 191 592 | 169 813 | 218 019 | 302 131 | 268 951 | 342 088 | 493 723 | 452 680 | 540 738 |

| NHS Hastings & Rother | 154 926 | 137 189 | 176 374 | 250 512 | 223 180 | 283 456 | 405 437 | 371 643 | 444 333 |

| NHS High Weald Lewes Havens | 147 565 | 130 527 | 168 136 | 238 262 | 212 312 | 269 596 | 385 827 | 353 598 | 422 781 |

| NHS Horsham and Mid Sussex | 204 605 | 181 100 | 233 058 | 327 619 | 291 826 | 370 788 | 532 224 | 487 776 | 583 181 |

| NHS North West Surrey | 313 628 | 277 273 | 357 608 | 486 200 | 431 785 | 551 734 | 799 828 | 731 970 | 877 549 |

| NHS Surrey Downs | 254 081 | 224 838 | 289 430 | 409 715 | 364 866 | 463 645 | 663 795 | 608 296 | 727 585 |

| NHS Surrey Heath | 87 667 | 77 529 | 99 936 | 135 585 | 120 544 | 153 728 | 223 252 | 204 471 | 244 782 |

| Thames Valley | 1 920 534 | 1 700 818 | 2 186 976 | 3 036 308 | 2 701 100 | 3 439 558 | 4 956 842 | 4 542 153 | 5 431 392 |

| NHS Aylesbury Vale | 184 797 | 163 568 | 210 488 | 290 629 | 258 621 | 329 144 | 475 426 | 435 577 | 520 969 |

| NHS Bracknell and Ascot | 127 869 | 113 255 | 145 576 | 205 782 | 183 246 | 232 856 | 333 651 | 305 853 | 365 418 |

| NHS Chiltern | 286 444 | 253 550 | 326 279 | 464 327 | 413 568 | 525 402 | 750 772 | 687 967 | 822 503 |