Abstract

Manganese oxide (MnO) nanocubes were fabricated and their surface were modified by ligand encapsulation or ligand exchange, to render them water-soluble. And then, MnO formed the hollow structure by etching using acidic solution (phthalate buffer, pH 4.0). Depending on the ligand of the MnO surface, it increases the interaction between MnO and water molecules. Also, the hollow structure of MnO, as well as the ligand, can greatly enhance the accessibility of water molecules to metal ions by surface area-to-volume ratio. These factors provide high R1 relaxation, leading to strong T1 MRI signal. We have confirmed T1-weighted MR contrast effect using 4-kinds of MnO nanocubes (MnOEn, MnOEnHo, MnOEx and MnOExHo). They showed enough a MR contrast effect and biocompatibility. Especially, among them, MnOExHo exhibited high T1 relaxivity (r1) (6.02 mM−1 s−1), even about 1.5 times higher sensitivity than commercial T1 MR contrast agents. In vitro/in vivo studies have shown that MnOExHo provides highly sensitive T1-weighted MR imaging, thereby improving diagnostic visibility at the disease site.

Keywords: Hollow nanostructure, Ligand encapsulation and exchange, Manganese oxide nanocube, MR imaging, T1 contrast agent

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not only able to provide anatomical images with significant spatial resolution and depth, but also attracts more and more attention due to its non-radioactive and non-invasive properties [1–5]. Two types of contrast agents are used for MRI scans. Negative contrast or T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images are generated by superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, reducing the spin–spin relaxation time of the water [6–9]. Positive contrast or proton MR images are generated by T1-based contrast agents such as manganese oxide (MnO) nanoparticles or gadolinium (Gd3+) to reduce spin–lattice relaxation time of nearby water molecules, resulting in the brightening of the voxel [10–13]. Tremendous research has led to significant advancements in technology and the controlled construction of nanomaterials. Chemical, physical, or biological methods can be used for the synthesis of nanomaterials, allowing for accurate control of their shape, composition, size and surface characteristics [14–18]. These parameters can be easily tailored to tune the physical and chemical properties of nanomaterials. Through decades of research, a diverse approach has been developed for the synthesis of MnO nanoparticles [10, 19–27]. Despite the increased interest, T1-based MRI is relatively limited due to ratiometric complications and low signal intensities. In addition, to influence the relaxation time, T1 contrast agent needs to interact directly with the surrounding water protons [28–30]. In case of nanospheres, only ions that are exposed on the surface are effective. Reducing the particle size on the basis of the same concentration of ions that make up the particle can provide a larger surface area. Additionally, by transforming the particles to the hollow structures, the particle surface percentage can be increased, which can, in turn, provide higher relaxivity. Hollow particles can offer high specific area and have excellent penetration and permeability. The volumetric capacity is quite high, which allows access to more water molecules to improve MR contrast [31, 32]. In addition, ligand exchange can make the surface hydrophilic, which further enhances the contrast compared to bilayer coated particles. Hydrophobic inner coating can hinder moisture penetration and reduce spin effect [33–36]. Until now, several hollow MnO-based nanoparticles have been developed, including MnO particles loaded with iron oxide nanoparticles or drug molecules [37–39]. Despite this development, hollow MnO particles have not been optimized for low relaxation and maximum contrast enhancement.

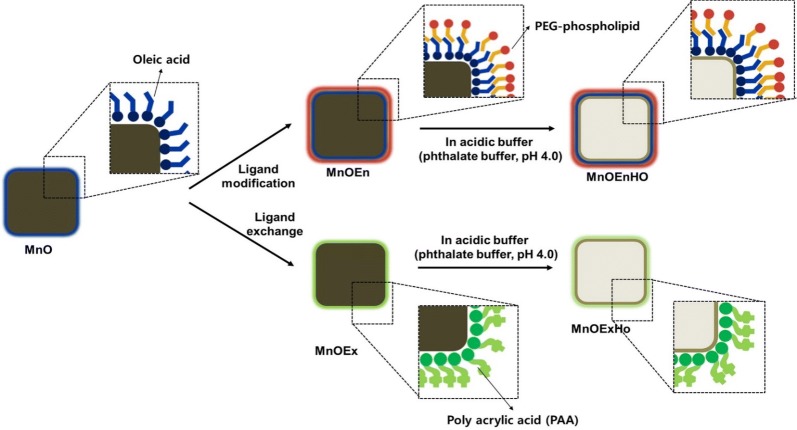

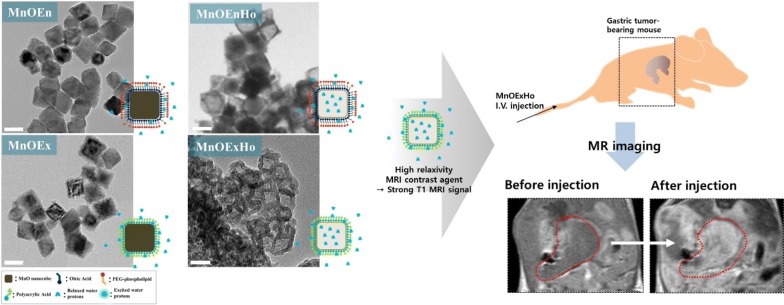

Herein, we report on the development of four water-soluble MnO nanocubes, namely (1) MnOEn: poly(ethylene glycol) phospholipid-encapsulated MnO nanocubes (2) MnOEnHO: hollow poly (ethylene glycol) phospholipid-encapsulated MnO nanocubes (3) MnOEx: ligand (polyacrylic acid)-exchanged MnO nanocubes, and (4) MnOExHo: hollow ligand (polyacrylic acid)-exchanged MnO nanocubes. The ability to tailor MnO nanocubes for maximum contrast enhancement along with changes in their chemical and physical structure, MR properties, and biocompatibility has been demonstrated (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the synthetic procedure of MnOEn, MnOEnHo, MnOEx and MnOExHo using MnO

Results and discussion

Synthesis and modification of MnO nanocubes

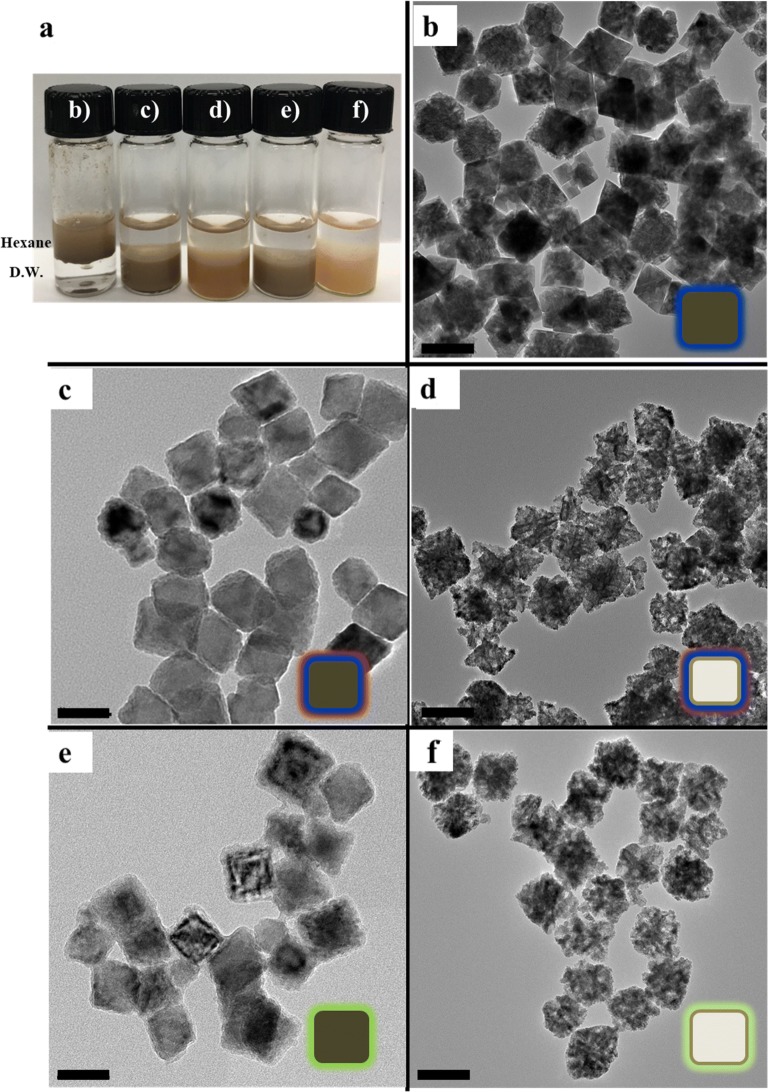

Monodisperse MnO nanocubes were synthesized by the thermal decomposition of manganese oleate complexes at a high temperature in a nonpolar organic solvent. The TEM images of the as-prepared MnO nanocubes show that the nanoparticles exhibit uniform size of 70 nm (length, l) and 65 nm (width, w) with high monodispersity (Fig. 2b). Following the synthesis of the MnO nanocubes, surface modification was performed to transfer MnO into the aqueous phase (D.W.). The outer surface of the MnO nanocubes was modified either by surface encapsulation (MnOEn) using poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-phospholipid (Fig. 2c) or by ligand exchange (MnOEx) using polyacrylic acid (PAA) (Fig. 2e). In both cases, the nanoparticles were well-dispersed in the aqueous phase. Next, etching using an acidic solution (phthalate buffer, pH 4.0) was performed to form hollow MnO (MnOEnHo and MnOExHo) nanocubes (Fig. 2d, f). When the area around the MnO particles was acidic condition, the surface part was etched. In particular, it was known that in the phthalate buffer (pH = 4.0), the center of the particle was made hollow structure as the surroundings were etched [30, 31]. During etching, the particles formed a clear and light-brown solution, and the carved MnO core adhered itself to the magnetic bar. The entire process was simple and highly reproducible. The as-prepared MnO, MnOEn, MnOEnHo, MnOEx, and MnOExHo were characterized by HR-TEM (Fig. 2), which clearly shows that the synthesized nanoparticles retained the size and shape uniformity of the original MnO nanocubes. Furthermore, their successful phase transfer from an oil phase (hexane) to an aqueous solution (D.W.) was observed after surface ligand encapsulation or exchange from oleic acid to lipid or PAA, respectively (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a Photos of the dispersibility of MnO in oil phase (hexane) and each MnO nanocube in aqueous phase (D.W.). TEM images of b MnO, c MnOEn, d MnOEnHo, e MnOEx, and f MnOExHo (scale bar: 50 nm)

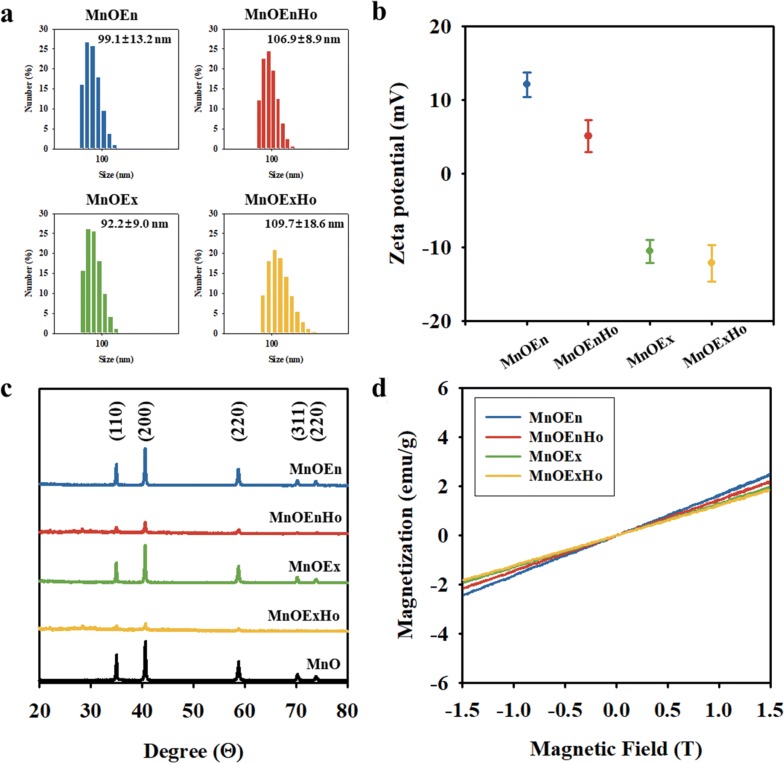

Characterization of MnO nanocubes

The size distribution of particles and their dispersion stability in the aqueous solution were measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis and zeta potential analyzer. DLS analysis defines the particles as spherical and measures the hydrodynamic diameter of the particles dispersed in the aqueous phase. Therefore, it is not accurate because it is in the form of a cube but its approximate hydrodynamic size and dispersibility in aqueous phase can be confirmed. There size were 99.1 ± 9.2 nm (MnOEn), 106.9 ± 8.9 nm (MnOEnHo), 92.2 ± 9.0 nm (MnOEx), and 109.7 ± 4.6 nm (MnOExHo), respectively (Fig. 3a). Especially, they exhibited low standard deviation, indicating that each particle were stably dispersed in the aqueous phase without aggregation. In addition, it was known that the surface charges were influenced by surface coating materials [40–44]. Therefore, the positive charges of MnOEn and MnOEnHo were attributed to the presence of amine groups in the lipid. Meanwhile, the negative charges of MnOEx and MnOExHo were attributed to the presence of carboxyl groups of PAA on their surfaces (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

a Size distributions histogram using dynamic light scattering analysis, b Zeta potential values, c X-ray diffraction patterns, and d magnetic hysteresis loop analyzed using vibrating sample magnetometer [MnOEn (blue line), MnOEnHo (red line), MnOEx (green line), MnOExHo (yellow line), and MnO (black line)]

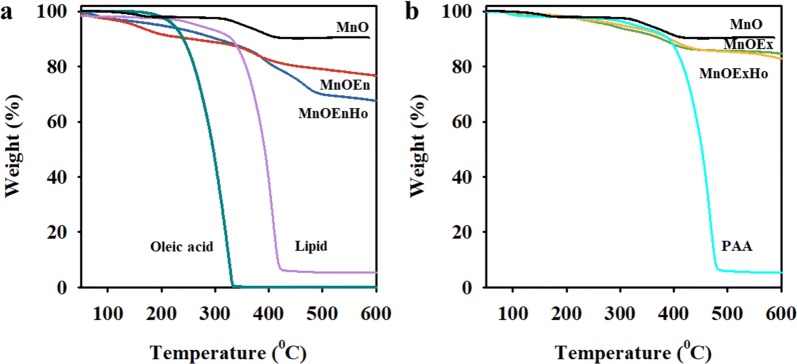

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) results of MnO, MnOEn, MnOEnHo, MnOEx, and MnOExHo indicate that the crystalline peaks match the series of Bragg reflections corresponding to the standard, and the phase pure cubic rock salt structure of MnO (a = 4.442 Å) was maintained even after ligand exchange and surface modification (Fig. 3c). The field-dependent magnetization curves for MnOEn, MnOEnHo, MnOEx, and MnOExHo showed similar magnetization values (1.82–2.41 emu/mg) in an external magnetic field of 1.5 T with no remanence coercivity at zero field, indicating that these particles exhibited paramagnetic properties at room temperature (Fig. 3d). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was used to confirm the ratio of surface modification on the surface of each MnO nanocube (Fig. 4). MnOEn contains 23.2 wt% of organic layer composed of oleic acid and PEG-phopholipid and 76.7 wt% of inorganic materials (MnO). After MnO etching, MnOEnHo was stably formed the hollow structure in MnO, so the ratio of organic layer in MnOEnHo increased to 32.4 wt% and the inorganic ratio decreased to 67.6 wt% (Fig. 4a). Likewise, MnOExHo had a less MnO ratio than MnOEx, indicating that the hollow structured nanocube was well formed (inorganic ratio in MnOEx: 84.8 wt% and inorganic ratio in MnOExHo: 83.1 wt%) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

TGA analysis of a MnO (black line), MnOEn (blue line), MnOEnHo (red line), oleic acid (cyan line) and lipid (light violet line), b MnO (black line), MnOEx (green line), MnOExHo (yellow line) and polyacrylic acid (PAA) (light blue line)

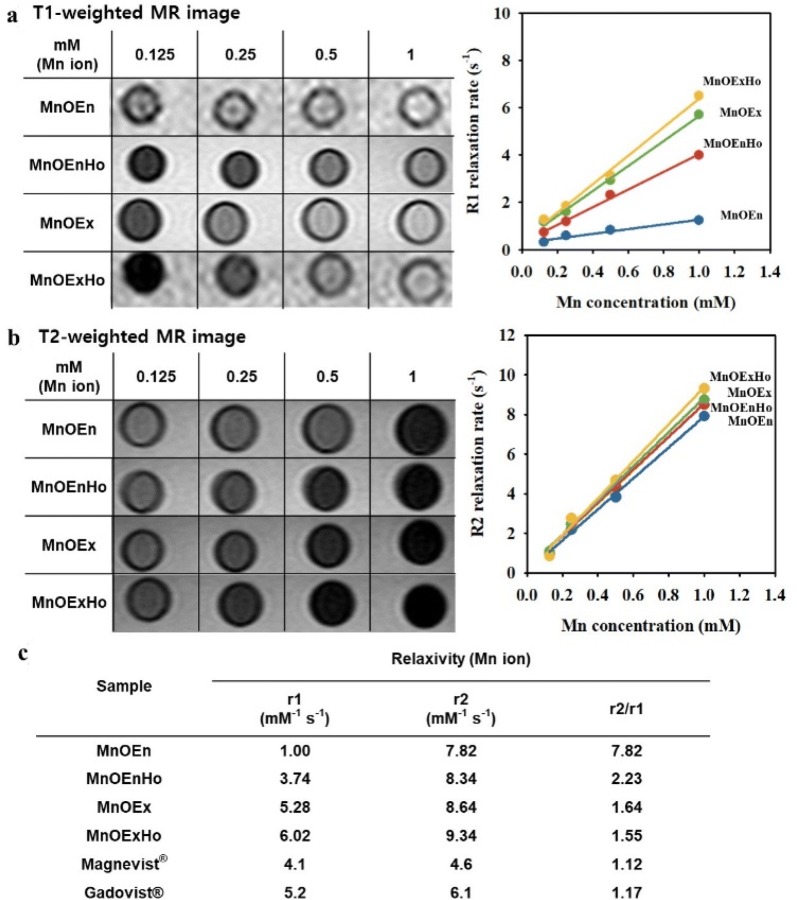

In addition, we evaluated the feasibility of nanoparticles as T1 MRI agents and confirmed their MR contrast effects. The T1-weighted MR images acquired on a 3.0 T MRI scanner reveal the concentration-dependent signal enhancement, which validates the advantage of hollow MnO nanocubes over solid MnO nanocubes. As indicated in Fig. 5a, the MnOEn, MnOEnHo, MnOEx, and MnOExHo at the same concentration of 1 mM (based on the Mn concentration measured by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy) clearly showed bright signal enhancement. When we measured their MR signal intensities in an aqueous phase under various concentration at room temperature, the T-1 weighted MR images showed an increasingly stronger bright image as the concentration increased. Among them, MnOExHo showed the strong T1 MR signals, as the Mn concentration increased, and corresponding the longitudinal relaxivity (r1) was 6.02 mM−1 s−1. It was 6.02, 1.61, and 1.14 times those of MnOEn (1.00 mM−1 s−1), MnOEnHo (3.74 mM−1 s−1), and MnOEx (5.28 mM−1 s−1), respectively. As well, T1 relaxivity (r1) of MnOExHo was higher (approximately 1.16–1.47-fold) that that of commercial T1 MRI contrast media (Magnevist®: 4.1 mM−1 s−1 and Gadovist®: 5.2 mM−1 s−1). These enhancements in MnOExHo and MnOEnHo can be attributed to the increased volumetric capacity to access water molecules, which leads to an enhanced spin effect. The greater signal enhancement of MnOExHo, when compared to MnOEnHo, could be due to the bilayer effect of MnOEnHo, that is, the presence of a hydrophobic layer decreases the accessibility of water molecules to the metal ions. Furthermore, the T2-weighted MR images were obtained for each MnO nanocube concentration (Fig. 5b). The transversal relaxivity (r2) of MnOExHo, calculated on the basis of the Mn ion concentration, was 9.34 mM−1 s−1, which was 1.19, 1.12, and 1.08 times those of MnOEn (7.82 mM−1 s−1), MnOEnHo (8.34 mM−1 s−1), and MnOEx (8.64 mM−1 s−1), respectively (Fig. 5b). It has been reported that the ideal T1 MRI contrast agent should have an r2/r1 ratio close to 1 (one) [45, 46]. As shown in Fig. 5c, MnOExHo had high r1 value (6.02 mM−1 s−1) and r2/r1 value close to 1 (1.55), confirming the sufficient ability of MnOExHo as a T1 MRI contrast agent.

Fig. 5.

a T1-weighted MR images and b T2-weighted MR images depending on the concentration of each particle and plots of each relaxation (1/T1 and 1/T2) against Mn concentration. c Calculation of R1 relaxivity (r1), R2 relaxivity (r2) and r2/r1 [MnOEn (blue line), MnOEnHo (red line), MnOEx (green line), and MnOExHo (yellow line)]

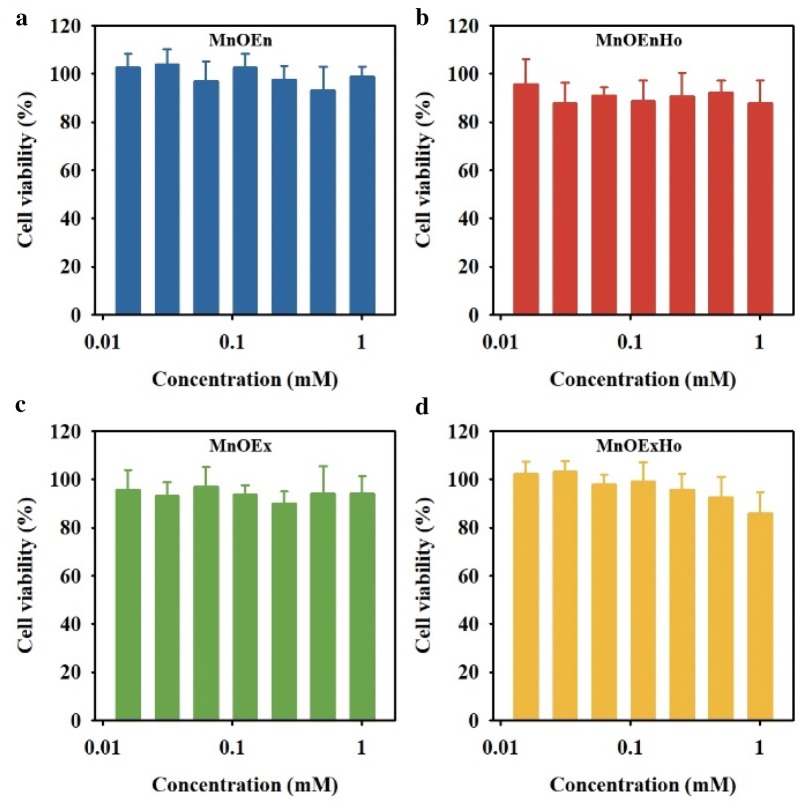

Cell viability of MnO nanocubes

The cellular cytotoxicity of the each MnO nanocubes was assessed in a gastric cancer cell line, SNU-484, using an MTT assay (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-y1)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide). As shown in Fig. 6, more than 80% of the cells survived at a high concentration of 1 mM all MnO nanocubes, indicating that these nanocubes showed biocompatibility even at high concentrations of MnO nanocubes.

Fig. 6.

Cell viability of SNU-484 cells incubated with a MnOEn (blue), b MnOEnHo (red), c MnOEx (green) and d MnOExHo (yellow) at various concentrations for 24 h at 37 °C

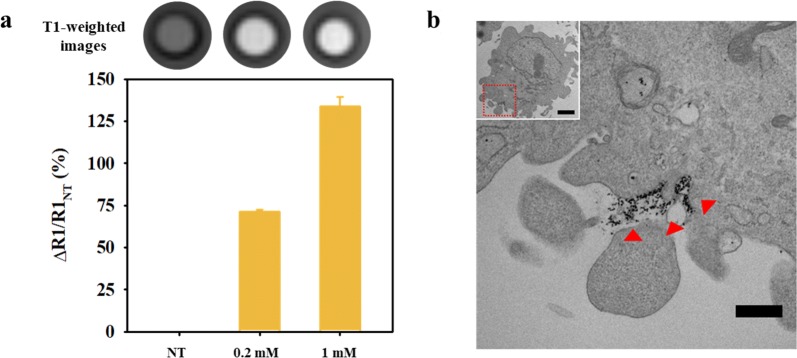

Cellular MR imaging using MnOExHo

Additionally, MnOExHo having the highest T1 MRI sensitivity was treated with SNU-484 cells to evaluate its diagnostic ability as T1 MRI contrast agent. The SNU-484 cells treated with MnOExHo at concentrations of 0.2 and 1 mM showed significant MR contrast effects. MnOExHo-treated cells definitely showed bright images compared with the untreated cells. The T1-weighted MR images gradually changed from dark black to bright white as the concentration of treated MnOExHo in the cells increases (Fig. 7a). MR signal intensity (ΔR1/R1NT, ΔR1 = R1 − R1NT) was higher in treated cells than in non-treated cell (NT) (MnOExHo (0.2 mM)-treated cells: 71%, MnOExHo (1.0 mM)-treated cells: 134%) (Fig. 7a). In the TEM images of the MnOExHo-treated cells, furthermore, many black dots were observed, indicating the entry of the MnOExHo nanocubes into the SNU-484 cells (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

a T1-weighted MR images and relative signal intensity graphs of SNU-484 cells incubated with MnOExHo (ΔR1 = R1 − R1NT, NT: no treatment), b TEM images of SNU-484 cells treated with MnOExHo (scale bar: 500 nm, inset scale bar: 2 μm)

In vivo MR imaging of MnOExHo

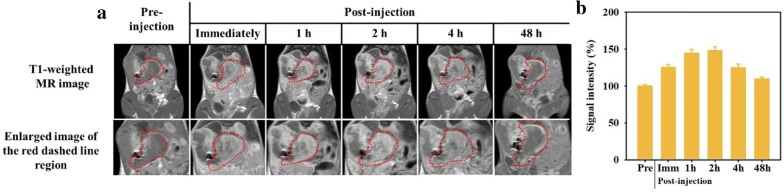

We next performed in vivo MRI using MnOExHo to evaluate their diagnostic ability as a T1 MRI contrast agent in tumor-bearing mice. Tumor-bearing mice with gastric cancer were prepared, and MnOExHo (200 μgMn/μl) were injected into mouse tail vein (intravenous injection). We monitored MR imaging at different time intervals (pre-injection, immediately following injection, and 1, 2, 4, and 48 h post-injection) (Fig. 8), before and after MnOExHo injection. As soon as MnOExHo injection, tumor region [red dashed line region) appeared bright in the T1 MR images with high MR signal intensity, compared with before injection (Fig. 8a)]. To obtain quantitative and dependable results for signal intensity measurements, we analyzed the MR signal in the tumor by drawing ROIs of whole tumor volumes on both the T1-weighted images (Fig. 8b). The T1 signal intensity gradually increased after administration of MnOExHo, and showed the highest signal enhancement of 144.3% (1.44 times) 1 h after injection. Especially, MR images at 1–2 h after injection showed the brightest images at the tumor region, and MR signal intensities were also increased with a similar trend to MR images (Fig. 8). This is because MnOExHo circulated in the blood stream and gradually accumulated in tumor tissues by the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. After 48 h, no bright image of the tumor area was seen, and the increased MR signal was reduced as before particle injection (pre-injection). We judged that MnOExHo accumulated in tumor within 1–2 h and then excreted out of the tumor up to 48 h.

Fig. 8.

a In vivo T1-weighted MR images and b their relative T1 signal intensity (%) (red dashed line region) of orthotopic gastric cancer mice model after intravenous injection of MnOExHo (200 μg Mn per mouse) at different time points (pre-injection, immediately after, and 1, 2, 4, and 48 h post-injection)

Conclusions

In this study, we developed various types of MnO nanocubes for using effective T1-weighted MRI agents. The as-synthesized MnO nanocubes were rendered water-soluble by ligand exchange and ligand encapsulation. Moreover, treatment with the acidic solution (phthalate buffer) was used to form hollow MnO nanocubes. Furthermore, it was confirmed that the hollow structure and the surface ligand exchange of the MnO nanocubes allow greater access of Mn ions to the water molecules, thus exhibiting a maximum enhancement of longitudinal relaxation time and inducing strong T1 MR signal. Therefore, this study suggest that MnOExHo could be used as effective T1 contrast agents for biomedical research.

Experimental methods

Materials

Diethylene glycol (DEG), manganese (II) formate [Mn(COOH)2], tri-n-octylamine (TOA), oleic acid (OA), and polyacrylic acid (PAA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ethanol, chloroform and a phthalate buffer (pH 4.0) were procured from Samchun Chemical. 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(aminoethylene glycol)-2000] (PEG-Phospholipid) (mPEG-2000 PE, Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.) was used as-purchased without any purification. All other reagents purchased from commercial sources were used as-obtained without further purification. Furthermore, ultrapure deionized water was used for all the synthesis processes.

Synthesis of MnO nanocubes

Mn(COOH)2 (1 mmol) was added to a mixture containing 3 mmol of TOA and 3 mmol of OA. The resulting mixture was heated to 130 °C under vacuum until all the moisture was removed. First, the solution was heated to 280 °C for 1 h and then refluxed at 330 °C, where its color changed from brownish red to green. Then, it was left for 1 h under N2 flow to yield uniform MnO nanocubes. Finally, it was allowed to cool at room temperature (25 °C). The resulting particles were precipitated by adding ethanol and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min; they were then washed with chloroform and ethanol twice and finally, dispersed in chloroform.

Fabrication of MnOEn and MnOEx

A total of 10 mg of organic dispersible MnO nanocubes was added to 10 mL of chloroform solution containing 50 mg of PEG-phospholipid in a ratio of 5:1. After evaporating the solvent, the solution was incubated at 80 °C in vacuum for 1 h. The addition of 20 mL of water resulted in a clear, dark-brown suspension. Next, centrifugation was performed at 21,000 rpm for 30 min, and the particles were ultimately dissolved in the aqueous phase. Ligand exchange reactions were performed to modify the surface of the hydrophobic oleate-capped MnO nanocubes. A solution containing 20 mL of DEG and 200 mg of PAA was heated to 200 °C under vacuum for 1 h with magnetic stirring, followed by refluxing under N2 for 2 h at the same temperature. Then, a solution of 40 mg MnO in 4 mL of hexane was immediately added to the flask, and the resulting mixture was maintained at 200 °C for another 6 h. After cooling the solution to room temperature, the resulting nanocubes were precipitated by adding ethanol and collected by centrifugation. The particles were ultimately dissolved in the aqueous phase.

Preparation of hollow-typed MnO nanocubes (MnOEnHo and MnOExHo)

A total of 10 mg of the synthesized MnOEn and MnOEx nanocubes was dispersed into 20 mL of phthalate buffer at pH 4.0 and stirred for 12 h to carve away the MnO core. The resulting particles (MnOEnHo and MnOExHo) were obtained by centrifugation and resuspension in distilled water.

Cell cytotoxicity assay

SNU-484 cells from a gastric cancer cell line were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). The cells were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic–antimitotic at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The in vitro cytotoxicity of each MnO nanocube was assessed by the standard MTT assay. The SNU-484 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 104 cells per well, and cultured in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, various concentrations of each MnO nanocube were added to the medium and the cells were further incubated for 24 h. Afterward, the media was removed and MTT1 solution was added; the cells were incubated for another 4 h. The medium was then replaced with MTT2 solution, and, after 24 h, measurements were recorded at an absorbance–wavelength of 575 nm and a reference wavelength of 650 nm, using a multimode microplate reader. The cell viabilities were determined by calculating the ratio of the intensity of purple formazan formed in the viable cells treated with the nanocubes to the intensity of that in the untreated control cells.

Cellular internalization of MnOExHo nanocubes

First, 2 × 107 SNU-484 cells suspended in PBS (1 mL) was incubated with MnOEnHo (14 μg and 70 μg, respectively) and additionally incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. MnOEnHo incubated SNU-484 cells were e-suspended in 200 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde for MR imaging analysis. Their relaxivity coefficient (mM−1 s−1) was equal to the ratio of R1 (1/T1, s−1) and the concentration of Mn. As well, the cellular internalization of the MnOExHo nanocubes was confirmed by TEM (JEOL-1011). SNU-484 cells (106 cells/well) were seeded onto six-well plates overnight and then incubated with the MnOExHo nanocubes (1 mM in medium) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. After incubation for 8 h, the SNU-484 cells treated with the MnOExHo nanocubes were washed thrice with a phosphate buffered solution (pH 7.4, 10 mM), trypsinized (0.5 mL), and subsequently, harvested. Then, following collection, the cells were fixed using the standard fixation and embedding protocol for resin-section transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and sectioned using a LEICA Ultracut UCT ultra-microtome (Leica Microsystems, Austria).

In vivo model procedure

All animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. To establish an orthotopic mouse model of gastric cancer, SNU-484 cells (1.0 × 107 cells) were implanted into the fundic glands of the stomachs of male mice (6-week-old balb/c-nude mice). Then, MRI was performed on five mice, 4 weeks after the tumor cell transplantation. When the tumor size reached approximately 500 mm3, water-soluble MnOExHo (200 μg) was injected intravenously into the tail vein.

MR imaging procedure

We performed MR imaging experiment of MnO nanocubes solution with a 3.0 T clinical MRI scanner with a micro-47 surface coil (Intera; Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands). The R1 relaxivity of various concentrations of MnO nanocubes was measured by the Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) sequence at room temperature with the following parameters: echo time (TE) = 60 ms, repetition time (TR) = 4000 ms, slice thickness = 2.0 mm, number of acquisitions = 1, and point resolution = 234 × 234 μm2. The relaxivity values of R1 were calculated by a series of T1 values, when plotted as 1/T1 versus [Mn]. The relaxivity coefficient (mM−1 s−1) was equal to the ratio of R1 (1/T1, s−1) and the nanoparticle concentration. In vitro/in vivo MRI experiments were performed using a 3.0 T clinical MRI instrument equipped with a micro-47 surface coil (Intera; Philips Medical Systems, Best, Netherlands). To acquire cellular T1-weighted MR images, following parameters were adopted: resolution = 234 × 234 mm, section thickness = 3.0 mm, TE = 18 ms, TR = 625 ms, and number of acquisitions = 2. For T1-weighted MR images of the nude mice, the following parameters were adopted: resolution = 234 × 234 mm, section thickness = 2.0 mm, TE = 60 ms, TR = 4000 ms, and number of acquisitions = 1.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (NRF-2018M3A9E2022819 and 2018M3A9E2022821), the Basic Science Research Program of the NRF funded by MSIT (NRF2018R1C1B6005424) and (NRF-2017M3A9G5083322), and the KRIBB Research Initiative Program. The work was supported by the Development of Platform Technology for Innovative Medical Measurements Program (KRISS-2019-GP2019-0013) from the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science and by the KRIBB Research Initiative Program of the Republic of Korea.

Abbreviations

- MnO

Manganese oxide

- En

Encapsulation

- Ex

Exchange

- Ho

Hollow

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- DEG

Diethylene glycol

- TOA

Trioctylamine

- OA

Oleic acid

- PAA

Polyacrylic acid

Authors’ contributions

SH, E-KL and Y-MH conceived and designed the experiments; BK, SH, M-KS, and YC performed the experiments; AK and H-YS analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (NRF-2018M3A9E2022819 and 2018M3A9E2022821), the Basic Science Research Program of the NRF funded by MSIT (NRF2018R1C1B6005424) and (NRF-2017M3A9G5083322), and the KRIBB Research Initiative Program. The work was supported by the Development of Platform Technology for Innovative Medical Measurements Program (KRISS-2019-GP2019-0013) from the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science and by the KRIBB Research Initiative Program of the Republic of Korea.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional file.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Aastha Kukreja and Byunghoon Kang contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Aastha Kukreja, Email: kukreja.aastha@gmail.com.

Byunghoon Kang, Email: vv345@yonsei.ac.kr.

Seungmin Han, Email: seungminhan@arizona.edu.

Moo-Kwang Shin, Email: shinmkw@hanmail.net.

Hye Young Son, Email: shy916@yuhs.ac.

Yuna Choi, Email: YUNA517@yuhs.ac.

Eun-Kyung Lim, Email: eklim1112@kribb.re.kr.

Yong-Min Huh, Email: ymhuh@yuhs.ac.

Seungjoo Haam, Email: haam@yonsei.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Aaron Joseph AB, Villaraza L, Brechbiel MW. Macromolecules, dendrimers, and nanomaterials in magnetic resonance imaging: the interplay between size, function, and pharmacokinetics. Chem. Rev. 2010;110(5):2921–2959. doi: 10.1021/cr900232t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haacke EM, Cheng NY, House MJ, Liu Q, Neelavalli J, Ogg RJ, Khan A, Ayaz M, Kirsch W, Obenaus A. Imaging iron stores in the brain using magnetic resonance imaging. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2005;23(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huh YM, Jun YW, Song HT, Kim S, Choi JS, Lee JH, Yoon S, Kim KS, Shin JS, Suh JS, Cheon J. In vivo magnetic resonance detection of cancer by using multifunctional magnetic nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127(35):12387–12391. doi: 10.1021/ja052337c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang B, Cha B, Kim B, Han S, Shin MK, Jang E, Kim HO, Bae SR, Jeong U, Moon I, Son H, Huh YM, Haam S. Serially ordered magnetization of nanoclusters via control of various transition metal dopants for the multifractionation of cells in microfluidic magnetophoresis devices. Anal. Chem. 2016;88(2):1078–1082. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8(9):700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrow M, Taylor A, Murray P, Rosseinsky MJ, Adams DJ. Design considerations for the synthesis of polymer coated iron oxide nanoparticles for stem cell labelling and tracking using mri. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44(19):6733–6748. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00331H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee N, Hyeon T. Designed synthesis of uniformly sized iron oxide nanoparticles for efficient magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41(7):2575–2589. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15248C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim B, Yang J, Lim E-K, Park J, Suh J-S, Park HS, Huh Y-M, Haam S. Double-ligand modulation for engineering magnetic nanoclusters. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013;8(1):104–112. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-8-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim EK, Yang J, Dinney CP, Suh JS, Huh YM, Haam S. Self-assembled fluorescent magnetic nanoprobes for multimode-biomedical imaging. Biomaterials. 2010;31(35):9310–9319. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Na HB, Lee JH, An K, Park YI, Park M, Lee IS, Nam DH, Kim ST, Kim SH, Kim SW, Lim KH, Kim KS, Kim SO, Hyeon T. Development of a t1 contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging using mno nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007;46(28):5397–5401. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor KM, Rieter WJ, Lin W. Manganese-based nanoscale metal-organic frameworks for magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130(44):14358–14359. doi: 10.1021/ja803777x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caravan P. Protein-targeted gadolinium-based magnetic resonance imaging (mri) contrast agents design and mechanism of action. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42(7):851–862. doi: 10.1021/ar800220p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallo J, Alam IS, Lavdas I, Wylezinska-Arridge M, Aboagye EO, Long NJ. Rgd-targeted mno nanoparticles as t1contrast agents for cancer imaging—the effect of peg length in vivo. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2014;2(7):868–876. doi: 10.1039/C3TB21422B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Sun Z, Deng Y, Zou Y, Li C, Guo X, Xiong L, Gao Y, Li F, Zhao D. Highly water-dispersible biocompatible magnetite particles with low cytotoxicity stabilized by citrate groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48(32):5875–5879. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sykes EA, Chen J, Zheng G, Chan WC. Investigating the impact of nanoparticle size on active and passive tumor targeting efficiency. ACS Nano. 2014;8(6):5696–5706. doi: 10.1021/nn500299p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anselmo AC, Menegatti S, Kumar S, Vogus DR, Tian LL, Chen M, Squires TM, Gupta AS, Mitragotri S. Platelet-like nanoparticles mimicking shape, flexibility, and surface biology of platelets to target vascular injuries. ACS Nano. 2014;8(11):11243–11253. doi: 10.1021/nn503732m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Culver KS, Shin YJ, Rotz MW, Meade TJ, Hersam MC, Odom TW. Shape-dependent relaxivity of nanoparticle-based t1 magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J. Phys. Chem.. C Nanomater. Interfaces. 2016;120(38):22103–22109. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b08362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang S, Zhang X, Jiang G, Zhu H, Guo S, Su D, Lu G, Sun S. Tuning nanoparticle structure and surface strain for catalysis optimization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136(21):7734–7739. doi: 10.1021/ja5030172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas FJ, MacLaren DA, Tuna F, Holmes WM, Berry CC, Murrie M. Formation of octapod mno nanoparticles with enhanced magnetic properties through kinetically-controlled thermal decomposition of polynuclear manganese complexes. Nanoscale. 2014;6(1):172–176. doi: 10.1039/C3NR04832B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.An K, Park M, Yu JH, Na HB, Lee N, Park J, Choi SH, Song IC, Moon WK, Hyeon T. Synthesis of uniformly sized manganese oxide nanocrystals with various sizes and shapes and characterization of their t1 magnetic resonance relaxivity. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012;2012(12):2148–2155. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201101193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park J, Kang E, Bae CJ, Park J-G, Noh H-J, Kim J-Y, Park J-H, Park HM, Hyeon T. Synthesis, characterization, and magnetic properties of uniform-sized mno nanospheres and nanorods. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108(36):13594–13598. doi: 10.1021/jp048229e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neves HR, Bini RA, Barbosa JHO, Salmon CEG, Varanda LC. Dextran-coated antiferromagnetic mno nanoparticles for at1-mri contrast agent with high colloidal stability. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2016;33(3):167–176. doi: 10.1002/ppsc.201500251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im GH, Kim SM, Lee DG, Lee WJ, Lee JH, Lee IS. Fe3O4/MnO hybrid nanocrystals as a dual contrast agent for both T1- and T2-weighted liver mri. Biomaterials. 2013;34(8):2069–2076. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das B, Girigoswami A, Pal P, Dhara S. Manganese oxide-carbon quantum dots nano-composites for fluorescence/magnetic resonance (T1) dual mode bioimaging, long term cell tracking, and ros scavenging. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019;102(102):427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang M, Zhao W, Lei S, Zou W, Hu W, Liu H, Guo Z, Ren L, Zhou X, Chen Z. Rational design of mno nanoparticles assemblies for sensitive magnetic relaxation detection of melamine. Talanta. 2020;208:120359. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim MH, Son HY, Kim GY, Park K, Huh YM, Haam S. Redoxable heteronanocrystals functioning magnetic relaxation switch for activatable T1 and T22 dual-mode magnetic resonance imaging. Biomaterials. 2016;101(101):121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chevallier P, Walter A, Garofalo A, Veksler I, Lagueux J, Bégin-Colin S, Felder-Flesch D, Fortin MA. Tailored biological retention and efficient clearance of pegylated ultra-small mno nanoparticles as positive mri contrast agents for molecular imaging. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2014;2(13):1779–1790. doi: 10.1039/C3TB21634A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aime S, Frullano L, Geninatti Crich S. Compartmentalization of a gadolinium complex in the apoferritin cavity a route to obtain high relaxivity contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41(6):1017–1019. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<1017::AID-ANIE1017>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim EK, Kang B, Choi Y, Jang E, Han S, Lee K, Suh JS, Haam S, Huh YM. Gadolinium-based nanoparticles for highly efficient t1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Nanotechnology. 2014;25(24):245103. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/25/24/245103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim T, Cho EJ, Chae Y, Kim M, Oh A, Jin J, Lee ES, Baik H, Haam S, Suh JS, Huh YM, Lee K. Urchin-shaped manganese oxide nanoparticles as ph-responsive activatable t1 contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50(45):10589–10593. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin J, Anisur RM, Ko MK, Im GH, Lee JH, Lee IS. Hollow manganese oxide nanoparticles as multifunctional agents for magnetic resonance imaging and drug delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48(2):321–324. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng Y-K, Liu C-L, Chen H-C, Hsiao Y-H, Liu W-L, Tang K-C, Chi Y, Hsiao J-K, Lim K-E, Liao H-E, Shyue J-J, Chou P-T. A new and facile method to prepare uniform hollow MnO/functionalized mSiO2 core/shell nanocomposites. ACS Nano. 2011;5(5):4177–4187. doi: 10.1021/nn200928r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park J, Bang D, Kim E, Yang J, Lim E-K, Choi J, Kang B, Suh J-S, Park HS, Huh Y-M, Haam S. Effect of ligand structure on mno nanoparticles for enhancedt1magnetic resonance imaging of inflammatory macrophages. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012;2012(36):5960–5965. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201201026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen N, Shao C, Qu Y, Li S, Gu W, Zheng T, Ye L, Yu C. Folic acid-conjugated mno nanoparticles as a t1 contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging of tiny brain gliomas. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6(22):19850–19857. doi: 10.1021/am505223t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang J, Xie J, Chen K, Bu L, Lee S, Cheng Z, Li X, Chen X. Hsa coated mno nanoparticles with prominent mri contrast for tumor imaging. Chem. Commun. 2010;46(36):6684–6686. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01041c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang J, Chandrasekharan P, Liu XL, Yang Y, Lv YB, Yang CT, Ding J. Manipulating the surface coating of ultra-small gd2o3 nanoparticles for improved t1-weighted mr imaging. Biomaterials. 2014;35(5):1636–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bae KH, Lee K, Kim C, Park TG. Surface functionalized hollow manganese oxide nanoparticles for cancer targeted sirna delivery and magnetic resonance imaging. Biomaterials. 2011;32(1):176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang X, Liu Z-H, Zhang C, Yang Z, Wang Z. Synthesis and capacitive property of hierarchical hollow manganese oxide nanospheres with large specific surface area. J. Power Sources. 2009;193(2):939–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.04.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An K, Kwon SG, Park M, Na HB, Baik S-I, Yu JH, Kim D, Son JS, Kim YW, Song IC, Moon WK, Park HM, Hyeon T. Synthesis of uniform hollow oxide nanoparticles through nanoscale acid etching. Nano Lett. 2008;8(12):4252–4258. doi: 10.1021/nl8019467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gee A, Xu X. Surface functionalisation of upconversion nanoparticles with different moieties for biomedical applications. Surfaces. 2018;1(1):96–121. doi: 10.3390/surfaces1010009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGill SL, Smyth HDC. Disruption of the mucus barrier by topically applied exogenous particles. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7(6):2280–2288. doi: 10.1021/mp100242r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Elia G, Lynch I, Cedervall T, Dawson KA. Nanoparticle size and surface properties determine the protein corona with possible implications for biological impacts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105(38):14265–14270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelf TA, Sreenivasan VKA, Sun J, Kim EJ, Goldys EM, Zvyagin AV. Non-specific cellular uptake of surface-functionalized quantum dots. Nanotechnology. 2010;21(28):285105–285113. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/28/285105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendez-Gonzalez D, Laurenti M, Latorre A, Somoza A, Vazquez A, Negredo AI, López-Cabarcos E, Calderón OG, Melle S, Rubio-Retama J. Oligonucleotide sensor based on selective capture of upconversion nanoparticles triggered by target-induced DNA interstrand ligand reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9(14):12272–12281. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b00575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bony BA, Baeck JS, Chang Y, Bae JE, Chae KS, Lee GH. A highly efficient new T1 MRI contrast agent with r2r1 ≈ 1.0: mixed Cu(II)Gd(III) oxide nanoparticle. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2015;36(4):1203–1208. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bao Y, Sherwood JA, Sun Z. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as T1 contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2018;6(6):1280–1290. doi: 10.1039/C7TC05854C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional file.