Abstract

Background

Given the central role of radiology in patient care, it is important that radiological research is grounded in reproducible science. It is unclear whether there is a lack of reproducibility or transparency in radiologic research.

Purpose

To analyze published radiology literature for the presence or lack of key indicators of reproducibility.

Methods

This cross-sectional retrospective study was performed by conducting a search of the National Library of Medicine (NLM) for publications contained within journals in the field of radiology. Our inclusion criteria were being MEDLINE indexed, written in English, and published from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018. We randomly sampled 300 publications for this study. A pilot-tested Google form was used to record information from the publications regarding indicators of reproducibility. Following peer-review, we extracted data from an additional 200 publications in an attempt to reproduce our initial results. The additional 200 publications were selected from the list of initially randomized publications.

Results

Our initial search returned 295,543 records, from which 300 were randomly selected for analysis. Of these 300 records, 294 met inclusion criteria and 6 did not. Among the empirical publications, 5.6% (11/195, [3.0–8.3]) contained a data availability statement, 0.51% (1/195) provided clear documented raw data, 12.0% (23/191, [8.4–15.7]) provided a materials availability statement, 0% provided analysis scripts, 4.1% (8/195, [1.9–6.3]) provided a pre-registration statement, 2.1% (4/195, [0.4–3.7]) provided a protocol statement, and 3.6% (7/195, [1.5–5.7]) were pre-registered. The validation study of the 5 key indicators of reproducibility—availability of data, materials, protocols, analysis scripts, and pre-registration—resulted in 2 indicators (availability of protocols and analysis scripts) being reproduced, as they fell within the 95% confidence intervals for the proportions from the original sample. However, materials’ availability and pre-registration proportions from the validation sample were lower than what was found in the original sample.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate key indicators of reproducibility are missing in the field of radiology. Thus, the ability to reproduce studies contained in radiology publications may be problematic and may have potential clinical implications.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, Reproducibility of results, Radiology, Transparency

Key points

Key indicators of reproducibility and transparency are frequently missing in the radiology literature.

The ability to reproduce the results of radiologic studies may be difficult.

Introduction

The field of radiology plays a significant role in the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of numerous disease processes. The importance of radiology to the field of medicine is evident by the large amount of annual expenditures on imaging, estimated to be 10% of total healthcare costs in the USA [1]. Advancements in imaging modalities and diagnostic testing are predicated upon robust and trustworthy research. Yet, the field of radiology has been known for low-level evidence study designs, with randomized trials, multicenter studies, and meta-analyses making up the smallest portion of publications (0.8 to 1.5%) [2]. With the movement toward patient-centered, evidence-based care, efforts are needed to ensure the robustness and reproducibility of radiology research.

Reproducibility—defined as the ability to conduct an independent replication study and reach the same or similar conclusions as the study in question [3, 4]—gained national attention after the majority of 1500 surveyed scientists reported failure to reproduce another scientist’s experiment and half being unable to reproduce their own experiments [5]. In radiology research, a lack of reproducibility has been partly attributed to imaging datasets too small to power a significant finding, models lacking independent validation, and improper separation of training and validation data [6]. Such practices may go undetected by editors, peer reviewers, and readers and contribute to downstream effects, such as irreproducible results and perpetuated errors in subsequent studies.

Given the central role of radiology to patient care, reproducible radiology research is necessary. In this study, we investigate radiology publications for key factors of reproducibility and transparency. Findings may be used to evaluate the current climate of reproducible research practices in the field and contribute baseline data for future comparison studies.

Materials and methods

Our investigation was designed as a cross-sectional meta-research study to evaluate specific indicators of reproducibility and transparency in radiology. The study methodology is a replication of work done by Hardwick et al. [7] with minor adjustments. Our analysis did not involve human subjects; thus, this investigation was not subject to institutional review board oversight [8]. Guidelines detailed by Murad and Wang were used for the reporting of our meta-research [9]. The Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used as necessary [10]. We supplied all protocols, raw data, and pertinent materials on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/n4yh5/). Amendments to our study, based upon peer review feedback following initial submission, are described in the protocol.

Journal and study selection

One investigator (D.T.) searched PubMed with the NLM subject term tag “Radiology[ST]” on June 5, 2019. D.T. extracted the electronic ISSN number (or linking ISSN if the electronic version was unavailable) for included journals. PubMed was searched using the list of ISSN (PubMed contains the MEDLINE collection) on June 5, 2019, to identify publications. A random sample of 300 was selected to have data extracted with additional publications available as needed (https://osf.io/n4yh5/). With the goal of creating a diverse spectrum of publications for our study, restrictions were not placed on specific study types.

Training

Three investigators (B.W., N.V., J.N.) underwent rigorous in-person training led by D.T. on data extraction and study methodology to ensure reliability between investigators. Training included a review of the following: objectives of the study, design of the study, protocol, Google form used for data extraction, and the process of extracting data. The process for extracting data was demonstrated via the use of 2 example publications. All investigators who underwent training independently conducted a blinded and duplicate extraction of data from 2 example publications. Once the mock data extraction was completed, the investigators (B.W., N.V., J.N.) convened and resolved any discrepancies present. The entire training session was recorded from the presenters’ point of view and was posted online for investigators to reference (https://osf.io/tf7nw/).

Data extraction

Once all required training was completed, data were extracted from publications. Data extraction began on June 09, 2019, and was completed on June 20, 2019. One investigator (B.W.) performed data extraction on 300 publications with the other two investigators (N.V. and J.N.) extracting from 150 each. We divided publications into two categories: (1) publications with empirical data (e.g., clinical trial, cohort, case series, case reports, case-control, secondary analysis, chart review, commentary [with data analysis], and cross-sectional) and (2) publications without empirical data. For the sake of this study, imaging protocols with no patients or intervention were considered non-empirical. Different study designs resulted in a variation of data collected from individual publications. We analyzed non-empirical studies for the following characteristics: funding source(s), conflict of interest declarations, open access, and journal impact factor (dates, 5-year impact factor). Case reports and case series are not typically expected to be reproducible with a pre-specified protocol [11]. As a result, data were extracted from them in an identical manner as publications which lacked empirical data. There was no expectation for meta-analyses and systematic reviews to contain additional materials, meaning a materials’ availability indicator was excluded from their analysis. For the purpose of our study, data were synonymous with raw data and considered unaltered data directly collected from an instrument. Investigators were prompted by the data extraction form to identify the presence or absence of necessary pre-specified indicators of reproducibility and are available here https://osf.io/3nfa5/. The Google form implemented added additional options in comparison to the form Hardwick et al. [7] used. Our form had additional study designs such as case series, cohort, secondary analysis, meta-analysis/systematic review, chart review, and cross-sectional. Sources of funding were more specific to include non-profit, public, hospital, university, and private/industry. Following data extraction, all three investigators convened and resolved any discrepancies by consensus. Though unnecessary for this study, a third party was readily available for adjudication.

Assessing open access

We systematically evaluated the accessibility of a full-text version of each publication. The Open-Access Button (https://openaccessbutton.org/) was used to perform a search using publication title, DOI, and/or PubMed ID. If search parameters resulted in an inaccessible article, Google Scholar and PubMed were searched using these parameters. If an investigator was still unable to locate a full-text publication, it was deemed inaccessible.

Evaluation of replication and whether publications were cited in research synthesis

Web of Science was searched for all studies containing empirical data. Once located on Web of Science, we searched for the following: (1) the number of times a publication was used as part of a subsequent replication study and (2) the number of times a publication was cited in a systematic review/meta-analysis. Titles, abstracts, and full-text manuscripts available on the Web of Science were used to analyze if a study was cited in a systematic review/meta-analysis or a replication study.

Reproducibility validation sample

Following peer-review, we extracted data from an additional 200 publications in an attempt to validate our results from the original 300. The additional 200 studies were selected from the list of initially randomized publications. The same authors (B.W., N.V., and J.N.) extracted data from the studies in a blind and duplicate manner identical to the original sample.

Statistical analysis

Statistics from each category of our analysis were calculated using Microsoft Excel. Excel functions were used to provide quantitative analysis with results characterized by frequencies, percentages, and 95% confidence intervals using the Wilson Score for binomial proportions (Dunnigan 2008).

Results

Journal and publication selection

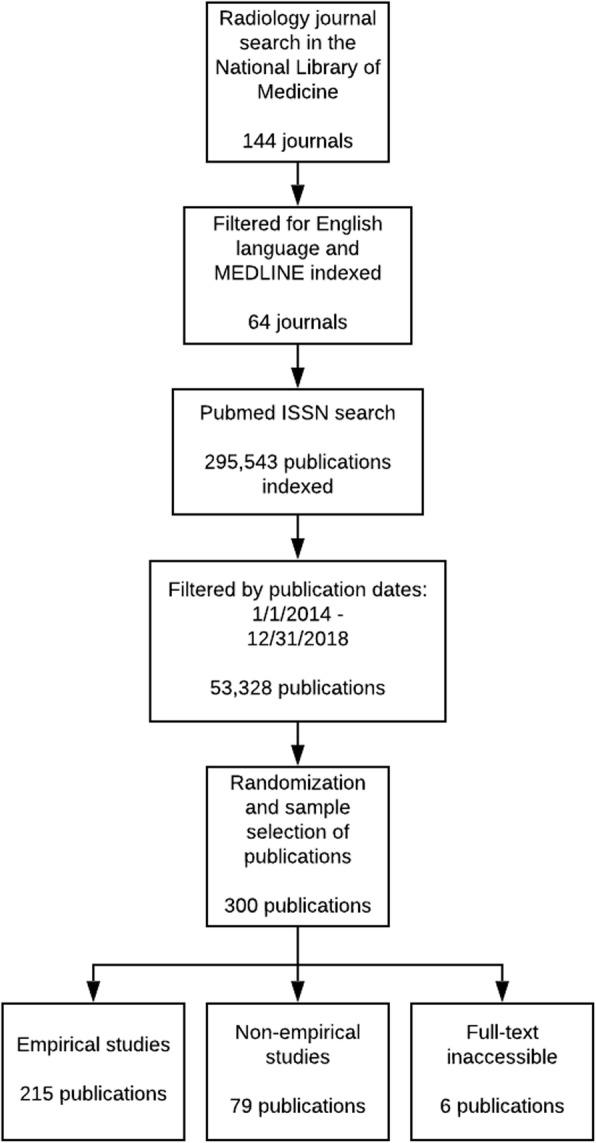

The NLM catalog search identified 144 radiology journals, but only 64 met the inclusion criteria. Our PubMed search of journals identified 295,543 radiology publications with 53,328 being published within the time-frame. We randomly sampled 300, but only 294 publications were accessible. Of the eligible publications, 215 contained empirical data and 79 did not (Fig. 1). Publications without empirical data were excluded from select analyses because they could not be assessed for reproducibility characteristics. Furthermore, 20 publications were identified as either case studies or case series; these research designs are unable to be replicated and were excluded from the analysis of study characteristics. Study reproducibility characteristics were analyzed for 195 radiology publications (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Publication selection process

Table 1.

Reproducibility indicators

| Reproducibility indicator | Role in producing transparent and reproducible science | Original sample (n = 300) |

|---|---|---|

| Articles | ||

| Article accessibility: articles were assessed for open accessibility, paywall access, or unable to access full text | Ease of access to publications enables interdisciplinary research by removing access barriers. Full-text access allows for validation through reproduction. | All (n = 300) |

| Funding | ||

| Funding statement: presence of funding sources of the study | Funding provides researchers the ability to create new experiments and tangibly investigate their ideas. However, funding sources can play a role in influencing how researchers conduct and report their study (e.g., scientific bias), which necessitates its disclosure. | All included publications† (n = 294) |

| Conflict of interest (COI) | ||

| COI statement: presence of conflict of interest statement | Conflict of interest conveys the authors’ potential associations that may affect the experimental design, methods, and analyses of the outcomes. Thus, full disclosure of possible conflicts allows for unbiased presentation of their study. | All included publications† (n = 294) |

| Data | ||

| Data statement: presence of a data availability statement, retrieval method, comprehensibility, and content | Raw data availability facilitates independent verification of research publications. It can improve accountability of outcomes reported and integrity of the research published. | Empirical publications‡ (n = 195) |

| Pre-registration | ||

| Pre-registration statement: presence of statement indicating registration, retrieval method, accessibility, and contents (hypothesis, methods, analysis plan) | Pre-registration explicitly reports aspects of the study design prior to the commencement of the research. Pre-registration functions as a way to limit selective reporting of results and prevents publication biases and P-hacking. | Empirical publications‡ (n = 195) |

| Protocols | ||

| Protocol statement: assessed for statement indicating protocol availability, and if available, what aspects of the study are available (hypothesis, methods, analysis plan) | Reproducibility of a study is dependent on the accessibility of the protocol. A protocol is a highly detailed document that contains all aspects of the experimental design which provides a step by step guide in conducting the study. | Empirical publications‡ (n = 195) |

| Analysis scripts | ||

| Analysis scripts statement: presence of analysis script availability statement, retrieval method, and accessibility | Analysis scripts are used to analyze data obtained in a study through software programs such as R, Python, and MatLab. Analysis scripts provide step by step instructions to reproduce statistical results. | Empirical publications‡ (n = 195) |

| Replication | ||

| Replication statement: Presence of statement indication a replication study. | Replication studies provide validation to previously done publications by determining whether similar outcomes can be acquired. | Empirical studies‡ (n = 195) |

| Materials | ||

| Materials statement: presence of a materials availability statement, retrieval method, and accessibility | Materials are the tools used to conduct the study. Lack of materials specification impedes the ability to reproduce a study. | Empirical publications¶ (n = 191) |

The indicators measured for the articles varied depending on its study type. More details about extraction and coding are available here https://osf.io/x24n3/

†Excludes publications that have no empirical data

‡Excludes case studies and case series

¶Excludes meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which materials may not be relevant, in addition to ‡

Sample characteristics

From our sample of 294 radiology publications, the publishing journals had a median 5-year impact factor of 2.824 (interquartile range 1.765–3.718). Study designs of sampled publications are made available in Table 2. The majority of authors were from the USA (102/294, 34.7%), followed by China (19/294, 6.5%). Humans were the most common test subjects (167/294, 56.8%). Most journals publishing the studies were from the USA (209/294, 71.1%), followed by the UK (44/294, 15.0%). A one-way ANOVA test to compare the effect of country of publication (USA, UK with Ireland, and Europe) on the number of reproducibility indicators demonstrated no significance [F(2, 283) = 2.83, p = .06]. Nearly half (149/300, 49.7%) of the eligible publications required paywall access. A correlation analysis found that publications that were not freely available through open access contained less indicators of reproducibility (r = − .51). More than half of the publications failed to provide a funding statement (176/294, 59.9%). Public funding accounted for 16% (47/294) of analyzed publications. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest (COI) in the majority of publications (156/294, 53.1% vs. 38/294, 12.9%). No COI statement was provided 34.0% (100/294) of the time.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included publications

| Characteristic | Original sample N (%) | Validation sample N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of studyN= 294 | No empirical data | 79 (26.9) | Type of studyN= 198 | 44 (22.2) |

| Clinical trial | 55 (18.7) | 55 (27.8) | ||

| Laboratory | 44 (15.0) | 43(21.7) | ||

| Chart review | 42 (14.3) | 12 (6.1) | ||

| Cohort | 19 (6.5) | 18 (9.1) | ||

| Case study | 18 (6.1) | 11 (5.6) | ||

| Survey | 12 (4.1) | 3 (1.5) | ||

| Cost effect | 7 (2.4) | 4 (2.0) | ||

| Case control | 6 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Cross-sectional | 5 (1.7) | 3 (1.5) | ||

| Meta-analysis | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Case series | 2 (0.7) | 3 (1.5) | ||

| Multiple | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Test subjectsN= 294 | Humans | 167 (56.8) | Test subjectsN= 198 | 108 (54.6) |

| Neither | 116 (39.5) | 77 (38.9) | ||

| Animals | 11 (3.7) | 13 (6.6) | ||

| Both | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Country of journal publicationN= 294 | US | 209 (71.1) | Country of journal publicationN= 198 | 128 (64.7) |

| UK | 44 (15.0) | 36 (18.2) | ||

| Germany | 6 (2.0) | 8 (4.04) | ||

| France | 5 (1.7) | 7 (3.54) | ||

| Japan | 3 (1.0) | 5 (2.53) | ||

| Canada | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Italy | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| India | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other | 21 (7.14) | 14 (7.1) | ||

| Country of corresponding authorN= 294 | US | 102 (34.7) | Country of corresponding authorN= 198 | 74 (37.4) |

| China | 19 (6.5) | 13 (6.6) | ||

| Germany | 17 (5.8) | 16 (8.1) | ||

| Japan | 17 (5.8) | 12 (6.1) | ||

| Australia | 15 (5.1) | 11 (5.6) | ||

| South Korea | 14 (4.8) | 12 (6.1) | ||

| Turkey | 13 (4.4) | 3 (1.5) | ||

| Canada | 13 (4.4) | 3 (1.5) | ||

| UK | 9 (3.1) | 7 (3.5) | ||

| Netherlands | 9 (3.1) | 6 (3.0) | ||

| France | 8 (2.7) | 9 (4.5) | ||

| Switzerland | 7 (2.4) | 5 (2.5) | ||

| India | 5 (1.7) | 2 (1.0) | ||

| Italy | 5 (1.7) | 2 (1.0) | ||

| Spain | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Unclear | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other | 36 (12.2) | 23 (11.6) | ||

| Open accessN= 300 | Yes found via open-access button | 80 (26.7) | Open accessN= 198 | 67 (33.8) |

| Yes found article via other means | 71 (23.7) | 23 (11.6) | ||

| Could not access through paywall | 149 (49.7) | 108 (54.5 | ||

| 5-year impact factorN= 272 | Median | 2.824 | 5 -year impact factorN= 182 | 2.89 |

| 1st quartile | 1.765 | 2.02 | ||

| 3rd quartile | 3.718 | 3.55 | ||

| Interquartile range | 1.953 | 1.53 | ||

| Most recent impact factor yearN= 300 | 2017 | 266 | Most recent impact factor yearN= 200 | 0 |

| 2018 | 10 | 186 | ||

| Not found | 24 | 14 | ||

| Most recent impact factorN= 276 | Median | 2.758 | Most recent impact factorN= 186 | 2.68 |

| 1st quartile | 1.823 | 1.94 | ||

| 3rd quartile | 3.393 | 3.79 | ||

| Interquartile range | 1.57 | 1.85 | ||

| Cited by systematic review or meta-analysisN= 211 | No citations | 193 (91.5) | Cited by systematic review or meta-analysisN= 151 | 132 (87.4) |

| A single citation | 11 (5.2) | 13 (8.6) | ||

| One to five citations | 7 (3.3) | 6 (4.0) | ||

| Greater than five citations | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Excluded in SR or MA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Cited by replication studyN= 211 | No citations | 211 (100) | Cited by replication studyN= 151 | 151 (100) |

| A single citation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| One to five citations | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Greater than five citations | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Excluded in SR or MA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

Reproducibility-related characteristics

Table 3 lists the 5 reproducibility indicators. Data availability was reported in 11 publications (11/195, 5.6%), but only 9 (9/11, 81.8%) had accessible data. Complete raw data were located in 0.51% of empirical publications (1/195). A materials’ availability statement was found in 23 publications (23/191, 12.0%), but only 18 (18/23, 78.3%) provided access to materials used in the study. Most publications did not provide a pre-registration statement (8/195, 4.1%) or protocol statement (4/195, 2.1%). Specifics of reproducibility-related characteristics are reported in supplemental Table 4. Among the 195 publications containing empirical data, none provided analysis scripts for the reproduction of statistical results (0/195, 0%). None of the publications reported a replication or novel study (0/195, 0%). Few publications were cited in SR or MA (21/211, 10.0%), with 13 cited a single time, 7 cited between two and five times, and 1 cited more than 5 times. There was no association between the number of times a publication had been cited, and the number of reproducibility indicators (− 0.002). None of the publications were cited in replication studies (0/211, 0%).

Table 3.

Reproducibility-related characteristics of included publications

| Characteristics | N (%) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open-accessN= 300 | No | 149 (49.7) | 44.0–55.3 |

| Yes | 151 (50.3) | 21.7–31.7 | |

| FundingN= 294 | No funding statement | 176 (59.9) | 54.3–65.4 |

| Public | 47 (16.0) | 11.8–20.1 | |

| No funding received | 28 (9.5) | 24.9–35.3 | |

| Multiple funding sources | 22 (7.5) | 4.5–10.5 | |

| Non-profit | 7 (2.4) | 0.7–4.1 | |

| University | 6 (2.0) | 0.4–3.6 | |

| Private/industry | 6 (2.0) | 0.0–1.6 | |

| Hospital | 2 (0.7) | 0.0–1.6 | |

| Conflict of interest statementN= 294 | No conflicts | 156 (53.1) | 47.4–58.7 |

| No statement | 100 (34.0) | 28.7–39.4 | |

| Conflicts | 38 (12.9) | 9.1–16.7 | |

| Data availabilityN= 195 | No statement | 184 (94.4) | 91.7–97.0 |

| Available* | 11 (5.6) | 3.0–8.3 | |

| Not available | 0 (0.0) | [0.0] | |

| Pre-registrationN= 195 | No statement | 187 (95.9) | [93.7–98.1] |

| Available* | 7 (3.6) | [1.5–5.7] | |

| Not available | 1 (0.5) | [0–1.3] | |

| ProtocolN= 195 | Not available | 191 (97.9) | [96.3–99.6] |

| Available* | 4 (2.1) | [0.4–3.7] | |

| Analysis scriptsN= 195 | No statement | 195 (100.0) | [100.0] |

| Not available | 0 (0.0) | [0.0] | |

| Available | 0 (0.0) | [0.0] | |

| Material availabilityN= 191* | No Statement | 168 (88.0) | [84.2–91.6] |

| Available* | 23 (12.0) | [8.4–15.7] | |

| Not available | 0 (0.0) | [0.0] | |

CI confidence interval

*Reproducibility-related characteristics that are available contain further specifications within Table 4

Table 4.

Specifications of reproducibility-related characteristics of included publications

| Characteristic specifications | N (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data available (n= 11) | Data retrieval | Supplementary information hosted by the journal | 10 (90.9) | ||||

| Online third party | 1 (9.1) | ||||||

| Upon request from authors | 0 (0.0) | ||||||

| Data accessibility | Yes, data could be accessed and downloaded | 9 (81.8) | |||||

| No, data count not be accessed and downloaded | 2 (18.2) | ||||||

| Data documentation§ | Yes, data files were clearly documented | 8 (88.9) | |||||

| No, data count not be accessed and downloaded | 1 (11.1) | ||||||

| Raw data availability§ | No, data files do not contain all raw data | 6 (66.7) | |||||

| Unclear if all raw data were available | 2 (22.2) | ||||||

| Yes, data files contain all raw data | 1 (11.1) | ||||||

| Materials available (n= 23) | Materials retrieval | Supplementary information hosted by the journal | 15 (65.2) | ||||

| Online third party | 4 (17.4) | ||||||

| In the paper | 4 (17.4) | ||||||

| Materials accessibility | Yes, materials could be accessed and downloaded | 18 (78.3) | |||||

| No, materials not be accessed and downloaded | 5 (21.7) | ||||||

| Protocol available (n= 4) | Protocol contents | Methods | 4 (100.0) | ||||

| Analysis plan | 0 (0.0) | ||||||

| Hypothesis | 0 (0.0) | ||||||

| Pre-registration available (n= 7) | Registry | ClinicalTrials.gov | 6 (85.7) | ||||

| Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trials | 1 (14.3) | ||||||

| Pre-registration accessibility | Yes, pre-registration could be accessed | 6 (85.7) | |||||

| No, pre-registration could not be accessed | 1 (14.3) | ||||||

| Pre-registration contents‖ | Methods | 6 (100.0) | |||||

| Hypothesis | 2 (33.3) | ||||||

| Analysis Plan | 0 (0.0) | ||||||

§Data specifications for documentation and raw data availability are provided if data was made accessible

‖Pre-registration specifications for contents are provided if pre-registration was made accessible

Reproducibility validation sample

Publication characteristics of the validation sample were very similar across all characteristics listed in Table 2. Of the 5 key indicators of reproducibility—availability of data, materials, protocols, analysis scripts, and pre-registration—the results of 2 indicators (availability of protocols and analysis scripts) were reproduced, as they fell within the 95% confidence intervals for the proportions from the original sample. Materials’ availability and pre-registration proportions from the validation sample were lower than what was found in the original sample.

Discussion

Our cross-sectional investigation found that key transparency and reproducibility-related factors were rare or entirely absent among our sample of publications in the field of radiology. No analyzed publications reported an analysis script, a minority provided access to materials, few were pre-registered, and only one provided raw data. While concerning, our findings are similar to those found in the social science and biomedical literature [7, 12]. Here, we will discuss 2 of the main findings from our study.

One factor that is important for reproducible research is the availability of all raw data. In radiology, clinical data and research data are often stored and processed in online repositories. Picture archives and communication systems, such as Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM), allow researchers to observe data code for details for image acquisition, patient positioning, image depth, and bit depth of an image [13]. For example, the osteoarthritis initiative has available and open-access datasets for testing image analysis algorithms. Furthermore, data sharing in radiology can be difficult as data is often in proprietary formats, too large to upload, or may contain private health information. Picture archiving and communication systems (PACS) have been developed for the purpose of storing and retrieving functional imaging data. Doran et al. have created a software prototype to combine the benefits of clinical and research designs to improve productivity and make data sharing more attainable [14]. Additionally, data sharing is uncommon potentially due to radiology journals lacking structured recommendations. Sardanelli et al. discovered only 1 of 18 general imaging journals had policies requesting data for submission [15]. By improving data sharing in radiology, others have the ability to critically assess the trustworthiness of data analysis and result interpretations [16]. For example, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) have established a policy which commends the dissemination of research results and datasets [17–19]. With more than 30 radiology and imaging journals being listed as ICMJE members, the ICMJE could have a substantial influence with the enforcement of this data sharing policy [20]. Journals in adherence with other policies have seen a substantial increase over time in studies with data availability statements [18]. A recent survey by the European Society of Radiology research committee found that 98% of respondents would be interested in sharing data, yet only 23 institutions (34%) had previously shared clinical trial data. From the data shared by these 23 institutions, at least 44 additional original works have been published [21].

A second factor lacking in radiology literature was having detailed analysis scripts publically available. In radiology research, many analytic decisions exist ranging from data management, artificial intelligence algorithms, biomarker identification with validation, and sharing necessary items (data, coding, statistics, protocol) [22–25]. A systematic review of 41 radiomic studies demonstrated 16 failing to report detailed software information, 2 failed to provide image acquisition settings, and 8 lacked detailed descriptions about any preprocessing modifications. These 3 methodological areas are important in radiological imaging studies as they can alter results significantly, thus decreasing the reproducibility of study findings [26]. A recent study by Carp et al. further tested possible variations in radiology imaging analysis by using a combination of 5 pre-processing and 5 modeling decisions for data acquisition in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). This modification in data collection created almost 7000 unique analytical pathways with varying results [27]. For research findings to be reproducible, a detailed analysis script with explicit software information and methodological decision making is necessary. A strategy to work around such complications is to use public repositories such as GitHub.com to provide the exact coding used to analyze study data. Authors can go one step further and provide their data analysis in a “container” such as docker or singularity, which replicate the study calculations in real time while being applicable to other data sets [28]. Investigators should be encouraged to take notes of analysis coding and scripts as to create a detailed explanation to be published with the study [29]. Triphan et al. provide a good example of providing publically available data analysis in the form of complete Python scripts that reproduce the study findings in real time and can be applied to other datasets [30, 31]. These analysis scripts improve the reproducibility of the study outcomes and will hopefully serve as a guide for future radiology publications to follow [25].

Implications moving forward

Our sample indicates there is room for improvement for the reporting of reproducibility-related factors in radiologic research. Ninety percent of scientists agree that science is currently experiencing a “reproducibility crisis” [5]. When asked how to improve reproducibility in science, a survey found that 90% of scientists suggested “more robust experimental designs, better statistics, and better mentorship” [5]. Here, we expand on how to implement and accomplish these suggestions. We also briefly discuss the role of artificial intelligence in contributing to research reproducibility.

More robust reporting

To create transparent and reproducible research, improved reporting is needed. For example, a study found irreproducible publications frequently contain inadequate documentation, reporting of methods, inaccessible protocols, materials, raw datasets, and analysis scripts [7, 12]. We encourage authors to follow reporting guidelines with a non-exhaustive list including Standards for Reporting Diagnostic accuracy studies (STARD for diagnostic accuracy studies) [32], Case Report (CARE for case reports and series) [33], and Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS for reliability and agreement studies) [34, 35]. In radiology, reliability and agreement studies are prevalent as interobserver agreement between radiologists is measured to identify the potential for errors in treatments or diagnostic imaging [36]. The GRRAS is a 15-item checklist required for study findings to be accurately interpreted and reproduced in reliability and agreement studies. Items such as sample selection, study design, and statistical analysis are often omitted by authors [36–38]. Researchers have had success with using the GRRAS specifically, but reporting guidelines in general provide the framework for studies to be understood by a reader, reproduced by researchers, used by doctors, and included in systematic reviews [37, 39, 40].

Better statistics

The current reproducibility crisis in part is tied to poor statistics. In psychology, a large-scale reproducibility study found that only 39 of 100 original psychology studies could be successfully replicated [41]. In response, the Association for Psychological Science has pioneered several innovations—such as statistical statcheck programs and statistical advisors—to provide expertise on manuscripts with sophisticated statistics or methodological techniques and to promote reproducibility within psychology [42]. Similar to the field of psychology, a study found that 147 of 157 articles published within radiology journals had statistical errors [43]. Based on these previous findings and our own, it is possible that radiology may be experiencing similar transparency and reproducibility problems and should consider promoting improved statistical practices by using a statistician to assist in the review process. StatReviewer [44]—an automated review of statistical tests and appropriate reporting—additionally may aid peer-reviewers whom are not formally trained to detect relevant statistical errors or detailed methodological errors.

Better mentorship

Quality research practices are constantly evolving, requiring authors to continually stay up to date, or risk being uninformed. Research mentors should oversee the continual education for graduate students, post-docs, fellows, researchers, and health care providers on areas such as experimental design, statistical techniques, and study methodology. We encourage multi-center collaboration and team science, where cohorts of scientists implement the same research protocols to obtain highly precise and reproducible findings [45–47].

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become an emerging tool within the field of radiology for physicians and researchers alike. The reproducibility of AI results in research projects is important as more data are being recorded and computed by programs without human intervention (Gundersen et al. 2017). Clinical radiology has shown similar increased usage of AI with the advent of algorithms to identify common pathology on chest films with an end goal of being applied to CTs or MRIs. In order for these imaging modalities to become a reality for clinicians, AI must be tested to produce reproducible findings and accurate diagnosis. Reproducibility and generalizability of AI results can be achieved for researchers and clinicians through the use of agreed-upon benchmarking data sets, performance metrics, standard imaging protocols, and reporting formats (Hosny et al. 2018).

Strengths and limitations

Regarding strengths, we randomly sampled a large selection of radiology journals. Our double data extraction methodology was performed in a similar fashion to systematic reviews by following the Cochrane Handbook [48]. Complete raw data and all relevant study materials are provided online to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Finally, we extracted data on a second random sample to validate and reproduce our initial results. This validation effort yielded similar results for some indicators and suggests some level of assurance concerning the stability of these estimates across samples. Regarding limitations, our analysis included only 300 of the 53,328 returned publications in the radiology literature; thus, our results may not be generalizable to publications in other time periods outside of our search or medical specialties. Our study focused on analyzing the transparency and reproducibility of the published literature in radiology, and as such, we relied solely on information reported within the publications. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that reproducibility-related factors are not available upon request from the author. Had we contacted the corresponding authors of the 300 analyzed publications, it is plausible we could have obtained more information.

Conclusion

With the potential lack of transparency and reproducibility practices in radiology, opportunities exist to improve radiology research. Our results indicate important factors for reproducibility and transparency are frequently missing in the field of radiology, leaving room for improvement. Methods to improve reproducibility and transparency are practical and applicable to many research designs.

Statistics and biometry

Matt Vassar has a Ph.D. in Research, Evaluation, Measurement, and Statistics and is the guarantor of the study.

Abbreviations

- COI

Conflicts of interest

- GRRAS

Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies

- ICMJE

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors

- ISSN

International Standard Serial Number

- NLM

National Library of Medicine

- PRISMA

The Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Authors' contributions

BW contributed to study design, data extraction, and drafted the manuscript. JN and NV both participated in data extraction and contributed to drafting the manuscript. AJ contributed to drafting the manuscript and study design. DT contribued to study design and drafting the manuscript. TB provided clinical expertise and contributed to drafting the manuscript. MV provided statistical analysis, study design, and contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded through the 2019 Presidential Research Fellowship Mentor – Mentee Program at Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work is not applicable to the Institutional Review Board oversight.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jackson WL (2014) Imaging utilization trends and reimbursement. Diagn Imaging.

- 2.Rosenkrantz AB, Pinnamaneni N, Babb JS, Doshi AM. Most common publication types in radiology journals: what is the level of evidence? Acad Radiol. 2016;23(5):628–633. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitcher RD. The role of radiology in global health. In: Mollura DJ, Culp MP, Lungren MP, editors. Radiology in Global Health: Strategies, Implementation, and Applications. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO | Medical imaging. February 2017. https://www.who.int/diagnostic_imaging/en/. Accessed June 27, 2019.

- 5.Baker M. 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature. 2016;533(7604):452–454. doi: 10.1038/533452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aerts HJWL. Data science in radiology: a path forward. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(3):532–534. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardwicke TE, Wallach JD, Kidwell MC, Bendixen T, Crüwell S, Ioannidis JPA (2019) An empirical assessment of transparency and reproducibility-related research practices in the social sciences (2014-2017). R Soc Open Sci 7(2):190806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Electronic Code of Federal Regulations-US Department of Health and Human Services’ Code of Federal Regulation 45 CFR 46.102(d). https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=&SID=83cd09e1c0f5c6937cd97513160fc3f&pitd=20180719&n=pt45.1.46&r=PART&ty=HTML#se45.1.46_1102 in effect July 19, 2018.

- 9.Murad MH, Wang Z. Guidelines for reporting meta-epidemiological methodology research. Evid Based Med. 2017;22(4):139–142. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallach JD, Boyack KW, Ioannidis JPA. Reproducible research practices, transparency, and open access data in the biomedical literature, 2015–2017. PLoS Biol. 2018;16(11):e2006930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iqbal SA, Wallach JD, Khoury MJ, Schully SD, Ioannidis JPA. Reproducible research practices and transparency across the biomedical literature. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(1):e1002333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Read Metadata from DICOM Files - MATLAB & Simulink. https://www.mathworks.com/help/images/read-metadata-from-dicom-files.html. Accessed August 4, 2019.

- 14.Doran SJ, d’Arcy J, Collins DJ, et al. Informatics in radiology: development of a research PACS for analysis of functional imaging data in clinical research and clinical trials. Radiographics. 2012;32(7):2135–2150. doi: 10.1148/rg.327115138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sardanelli F, Alì M, Hunink MG, Houssami N, Sconfienza LM, Di Leo G. To share or not to share? Expected pros and cons of data sharing in radiological research. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(6):2328–2335. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warren E. Strengthening research through data sharing. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):401–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naudet F, Sakarovitch C, Janiaud P et al (2018) Data sharing and reanalysis of randomized controlled trials in leading biomedical journals with a full data sharing policy: survey of studies published inThe BMJandPLOS Medicine. BMJ:k400. 10.1136/bmj.k400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Federer LM, Belter CW, Joubert DJ, et al. Data sharing in PLOS ONE: an analysis of data availability statements. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0194768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.0000-0003-1953-, 0000-0002-7378-. Making progress toward open data: reflections on data sharing at PLOS ONE | EveryONE: The PLOS ONE blog. EveryONE. https://blogs.plos.org/everyone/2017/05/08/making-progress-toward-open-data/. Published May 8, 2017. Accessed June 20, 2019.

- 20.ICMJE | Journals stating that they follow the ICMJE Recommendations. http://www.icmje.org/journals-following-the-icmje-recommendations/. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- 21.Bosserdt M, Hamm B, Dewey M (February 2019) Clinical trials in radiology and data sharing: results from a survey of the European Society of Radiology (ESR) research committee. Eur Radiol. 10.1007/s00330-019-06105-y [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Piccolo SR, Frampton MB. Tools and techniques for computational reproducibility. Gigascience. 2016;5(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13742-016-0135-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garijo D, Kinnings S, Xie L, et al. Quantifying reproducibility in computational biology: the case of the tuberculosis drugome. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gronenschild EHBM, Habets P, Jacobs HIL, et al. The effects of FreeSurfer version, workstation type, and Macintosh operating system version on anatomical volume and cortical thickness measurements. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parmar C, Barry JD, Hosny A, Quackenbush J, Aerts HJWL. Data analysis strategies in medical imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(15):3492–3499. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Traverso A, Wee L, Dekker A, Gillies R. Repeatability and reproducibility of radiomic features: a systematic review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102(4):1143–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carp J. On the plurality of (methodological) worlds: estimating the analytic flexibility of FMRI experiments. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:149. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poldrack RA, Gorgolewski KJ, Varoquaux G. Computational and informatic advances for reproducible data analysis in neuroimaging. Annu Rev Biomed Data Sci. 2019;2(1):119–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-072018-021237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorgolewski KJ, Poldrack RA. A practical guide for improving transparency and reproducibility in neuroimaging research. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(7):e1002506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Triphan S, Biederer J, Burmester K, et al. Raw data and analysis scripts for “Design and application of an MR reference phantom for multicentre lung imaging trials.” 2018. 10.11588/DATA/FHOCRZ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Triphan SMF, Biederer J, Burmester K, et al. Design and application of an MR reference phantom for multicentre lung imaging trials. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0199148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Altman DG, et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012799. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development | The EQUATOR Network. http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/care/. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 34.Reporting guidelines | The EQUATOR Network. http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 35.Guidelines for reporting reliability and agreement studies (GRRAS) were proposed | The EQUATOR Network. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/guidelines-for-reporting-reliability-and-agreement-studies-grras-were-proposed/. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 36.Kottner J, Audigé L, Brorson S, et al. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) were proposed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(1):96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerke O, Möller S, Debrabant B, Halekoh U (2018) Odense Agreement Working Group. Experience applying the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) indicated five questions should be addressed in the planning phase from a statistical point of view. Diagnostics (Basel) 8(4):69. 10.3390/diagnostics8040069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Cronin P, Rawson JV. Review of research reporting guidelines for radiology researchers. Acad Radiol. 2016;23(5):537–558. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.What is a reporting guideline? | The EQUATOR Network. http://www.equator-network.org/about-us/what-is-a-reporting-guideline/. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 40.Oster NV, Carney PA, Allison KH et al (2013) Development of a diagnostic test set to assess agreement in breast pathology: practical application of the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS). BMC Women’s Health 13(1). 10.1186/1472-6874-13-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Open Science Collaboration Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science. 2015;349(6251):aac4716. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.APS: Leading the Way in Replication and Open Science. Association for Psychological Science. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/publications/observer/obsonline/aps-reproducibility-and-replication-initiatives.html. Accessed June 30, 2019.

- 43.Günel Karadeniz P, Uzabacı E, Atış Kuyuk S, et al. Statistical errors in articles published in radiology journals. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2019;25(2):102–108. doi: 10.5152/dir.2018.18148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stat Reviewer. http://www.statreviewer.com/. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- 45.Klein RA, Ratliff K, Vianello M et al (2014) Investigating variation in replicability: a “many labs” replication project. Open Science Framework.

- 46.Klein RA, Vianello M, Hasselman F, et al. Many Labs 2: investigating variation in replicability across samples and settings. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science. 2018;1(4):443–490. doi: 10.1177/2515245918810225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munafò MR, Nosek BA, DVM B et al (2017) A manifesto for reproducible science. Nature Human Behaviour 1(1). 10.1038/s41562-016-0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Higgins JPT, Green S (2011) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons