Abstract

Cells depend on the asymmetric distribution of their components for homeostasis, differentiation and movement. In no other cell type is this requirement more critical than in the neuron where complex structures are generated during process growth and elaboration and cargo is transported over distances several thousand times the cell body diameter. Microtubules act both as dynamic structural elements and as tracks for intracellular transport. Microtubules are mosaic polymers containing multiple tubulin isoforms functionalized with abundant posttranslational modifications that are asymmetrically distributed in neurons. An increasing body of evidence supports the hypothesis that the combinatorial information expressed through tubulin genetic and chemical diversity controls microtubule dynamics, mechanics and interactions with microtubule effectors and thus constitutes a “tubulin code”. Here we give a brief overview of tubulin isoform usage and posttranslational modifications in the neuron, and highlight recent progress in understanding the molecular mechanisms of the tubulin code.

Introduction

The highly polarized architecture of the neuron underlies its ability to integrate and transmit information. The microtubule cytoskeleton provides not only structural scaffolding for the neuron but also participates in active functional polarization [1]. Microtubules are non-covalent polymers composed of αβ-tubulin heterodimers. Despite their common building block, they give rise to cellular structures with distinct architectures ranging from the transient bipolar mitotic spindle, to the highly complex neuronal microtubule arrays or the stable nine-fold symmetric axonemes in cilia and flagella. This diversity in cellular organization is reflected in the genetic and chemical diversity of the αβ-tubulin dimer through the expression of multiple α- and β-tubulin isoforms as well as chemically diverse and abundant posttranslational modifications that are temporally and spatially regulated [2*]. This diversity is especially high in neurons, which use multiple tubulin isoforms with abundant posttranslational modifications. The genetic and chemical diversity of the αβ-tubulin dimer was hypothesized to regulate intrinsic microtubule properties such as their dynamics as well as the recruitment and activity of motors and microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) and thus constitute a “tubulin code” [3; 4]. How the cell writes and reads the tubulin code has largely remained a mystery, but the advent of new tools for in vitro and in vivo manipulation and imaging has once again brought this fundamental problem into focus. We give a brief overview of microtubule cytoskeleton organization in neurons and the role of the tubulin code in defining neuronal asymmetry, briefly summarize our current knowledge of the tubulin isoform repertoire in the nervous system and highlight key recent advances in dissecting the molecular mechanisms used by cells to read and write the tubulin code.

Stereotyped organization and posttranslational modifications of microtubules in neurons

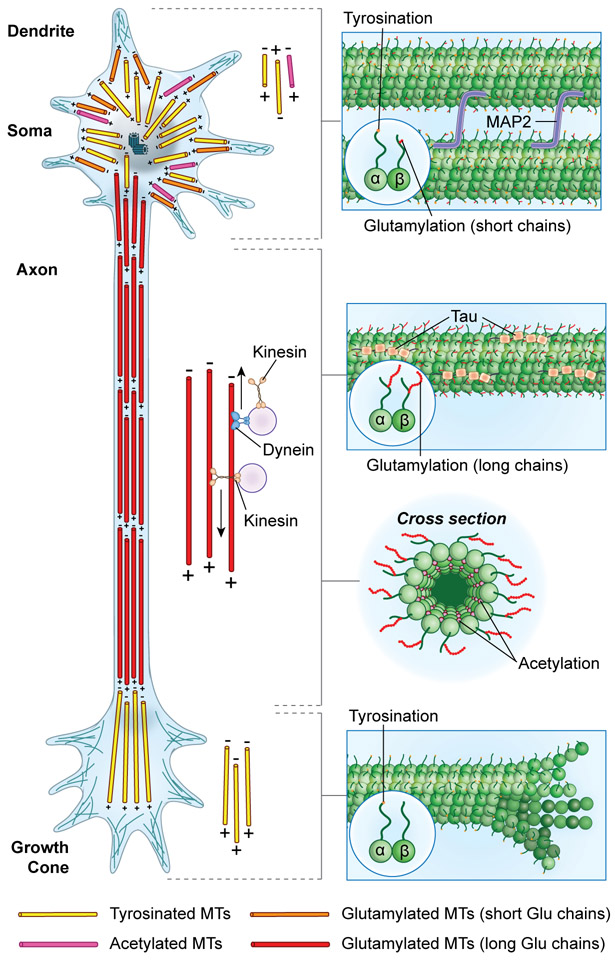

Microtubules are intrinsically polar polymers. Their minus ends are slow growing while plus ends are fast growing and dynamic. The polarity of microtubule arrays is stereotyped in neurons (reviewed in [5]). Axons contain tiled arrays of microtubules of varying lengths with the plus-end distal to the cell body. Dendrites have arrays of mixed polarities, with many microtubules oriented minus-end distal (Figure 1). While axons extend for long distances and are thin with tightly-bundled parallel microtubules, dendrites are highly branched to serve as effective receptors for the axons with which they synapse, consistent with their greater arborization and mixed polarity microtubule arrays. At the tip of the axon, the growth cone is populated by highly dynamic microtubules with their plus-ends distal (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stereotyped distribution of tubulin posttranslational modifications in the neuron.

Schematic of a neuron showing the distribution of tubulin modifications in the soma, dendrites, axon and growth cone. Insets show the microtubule surface covered with a lawn of disordered negatively-charged tubulin tails; from top to bottom (1) Microtubules in dendrites are tyrosinated and glutamylated with short glutamate chains; MAP2 concentrates in dendrites and interacts with tubulin tails (2) Microtubules in axons are detyrosinated, glutamylated with long glutamate chains; (3) Cross-section of a microtubule showing acetylation on lumenal Lys40; Tau concentrates in axons and interacts with tubulin tails (4) Dynamic microtubules in the growth cone are tyrosinated.

In addition to this polarization in their organization, microtubules are functionalized with abundant posttranslational modifications that are asymmetrically distributed in the neuron [6; 7; 8; 9**]. These modifications include the reversible removal and addition of a single tyrosine on the C-terminus of α-tubulin (detyrosination/tyrosination), removal of the α- tubulin penultimate glutamate (Δ−2), removal of the last two glutamates (Δ−3), and the addition and removal of single or multiple glutamates (glutamylation/deglutamylation) at internal positions on both the α- and β-tubulin tails, in addition to more conventional modifications such as phosphorylation. Glycylation, the addition of variable numbers of glycines has been so far limited to cilia or flagella (a detailed review of these modifications can be found in [2*] and [10*]). These modifications concentrate on the intrinsically disordered negatively charged C-terminal tails that decorate the outside of the microtubule and can provide significant binding surface for molecular effectors (Figure 1, insets). The microtubule lumen is also modified: Lys40 located in a flexible loop in the lumen is acetylated. In addition to these modifications on the flexible tails, residues in the folded tubulin core are also modified through methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, sumoylation and polyamination (reviewed in [2*] and [10*]).

Mixed-polarity microtubules in dendrites are enriched in tyrosination, acetylation, and short-chain glutamylation, whereas axonal microtubules are enriched in long-chain glutamylation, acetylation, polyamination, detyrosination and Δ−2 tubulin [6; 7; 8; 9**; 10*] (Figure 1). Dynamic presynaptic bouton and growth cone microtubules are primarily tyrosinated [6; 7; 8]. Recent work reveals a finer functionalization of microtubules in dendrites with the minus-end out stable bundles enriched in acetylation and dynamic microtubules with their plus-ends distal to the cell body enriched in tyrosination [9**] (Figure 1).

Tubulin isoforms have distinct biophysical properties and are functionally non-redundant

In addition to functionalizing tubulin through diverse and abundant posttranslational modifications, neurons also express multiple tubulin isoforms. Humans have eight α- and nine β-tubulin genes, respectively. Most are expressed in neurons [11]. In contrast, non-differentiated cells employ fewer isoforms [12**;13]. Tubulin isoforms are differentially expressed during neurogenesis, neuronal migration and synaptic connectivity, suggesting each isoform has unique properties suited to a developmental task [14]. Class III β-tubulin is expressed exclusively in neurons at the onset of differentiation where it is important for neurite formation [15]. It is also expressed in certain tumors of non-neuronal origins where it is not found before transformation [16; 17]. Not much is known about the distribution of tubulin isoforms in neurons. Recent high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by crosslinking immunoprecipitation revealed that Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), a microtubule plus-end tracking protein binds the 3’ UTR of TUBB2B for local translation at the growth cone periphery where it incorporates in dynamic microtubules [18], suggesting one potential strategy for local enrichment of tubulin isoforms.

Presently we know little about the effects of tubulin isotype composition on polymer structure, assembly and dynamics. Advances in obtaining single-isoform recombinant human tubulin [19; 20*] or tubulin purified from various sources using an affinity approach [21] finally allow the examination of isoform specific properties. Recent studies using these tools show that differences in tubulin isoforms can elicit large changes in microtubule dynamic parameters that are comparable to those induced by MAPs [12**; 20*; 22**]. Interestingly, neuronal βIII tubulin undergoes catastrophe (the transition between the growth and depolymerization phase) more frequently than non-neuronal specific isoforms (βI, II, and IVb) and can destabilize microtubules when titrated into more stable tubulin isoform mixtures [12**; 22**]. Thus, the increase in βIII levels during neurogenesis results in higher microtubule turnover. A recent study using electron microscopy revealed that an α-tubulin isotype in C. elegans (TBA-6) is essential for the doublet to singlet transition of ciliary microtubules in cephalic male neurons [23], highlighting the need for higher-resolution structural analyses of tubulin isoform mutants. The recent advances in Focused Ion Beam-Scanning Electron Microscopy (FIB-SEM) and cryo-EM tomography hold great promise in the acquisition of ultrastructural information to capture how isoform composition and tubulin modifications regulate axonal and dendritic microtubules in cases where gross differences might be difficult to discern.

Spatial Regulation of Motors and MAPs by the Tubulin Code

Its asymmetric architecture makes the neuron, more than any other cell type, highly dependent on precise and robust intracellular transport. Not surprising, traffic defects are a hallmark of neurodegenerative disease [24] and mutations in modifications enzymes have neuronal phenotypes [25; 26; 27; 28**]. Perturbations of tubulin modifications are also strongly associated with many neurodegenerative disorders (reviewed in [29]). While we understand how microtubule polarity organization directs motor traffic in the neuron (kinesin-mediated anterograde transport towards the distal axon and dynein-mediated retrograde transport towards the soma, for example), the role of tubulin modifications in specializing cellular microtubules for dedicated traffic is just now starting to be explored. Recent work revealed that microtubule bundles organized with their minus-end distal in the dendrite are acetylated, thus directing kinesin-1 out of dendrites and into the axon where the motor prefers acetylated microtubules [9**]. Thus, microtubule array architecture and chemical composition provide two interconnected levels of control for motor traffic in the neuron.

Recent studies also lend further support to the hypothesis that the stereotyped distribution of microtubule modifications in the neuron enables precise spatial regulation of cargo transport and microtubule dynamics. For example, the loading of retrograde vesicles is concentrated and restricted to the distal axon through a specific interaction of the Cap-Gly domains of microtubule end binding protein CLIP170 and the p150Glued dynactin subunit with tyrosinated microtubules that are enriched in this zone [30**]. Once loaded on the tyrosinated microtubule tips, the dynein/dynactin-propelled vesicles continue to move processively on the microtubule regardless of the tyrosination status [30**; 31*], ensuring effective transport down the axon.

While tyrosination is a simple ON/OFF switch, glutamylation, by virtue of the variable number of glutamates added to tubulin tails has the potential for a graded quantitative regulation of effectors. Recent work showed that glutamylation acts as a rheostat to control the activity of spastin, a microtubule-severing enzyme important in neurogenesis and axonal regeneration that is mutated in patients with hereditary spastic paraplegias, disorders characterized by axonopathy [32]. Maximal activity is seen at ~ 8 glutamates [33**]. Mass spectrometric analyses of tubulin purified from brain show a preponderance of glutamylated tubulin with 3–6 glutamates on each tail, with as many as eleven and seven detected on α- and β-tubulin tails, respectively [34]. As the neuron displays a gradient of glutamylation with a higher concentration of tubulin with higher numbers of glutamates in the axon, such a mechanism allows precise, substrate-regulated spatially-controlled severing in the neuron. Since multiple modifications can coexist on the same microtubule and microtubules with different modifications can be in close proximity, these recent studies foreshadow a highly complex combinatorial regulation by the tubulin code. The graded regulation of microtubule severing by glutamylation also underscores the need for more precise reporters of polymodifications such as glutamylation that are sensitive to the numbers of glutamates added to tubulin.

Neuronal microtubules are also decorated by a high-density of MAPs that regulate motor traffic. MAPs themselves can have stereotyped distributions in neurons and have been used as axonal (tau) or dendritic (MAP2) markers (Figure 1) [35; 36]. MAPs are prime candidates to be regulated by the tubulin code as many bind microtubules using the tubulin tails. Thus, motor traffic in the neuron is likely directed by a combination of the tubulin and MAP codes. The recent advances in obtaining engineered recombinant tubulin [12**; 19; 22**; 37] and quantitatively modified microtubules [33**] facilitated the above highlighted studies into the readout of the tubulin code through in vitro reconstitution [30**; 31*; 33**] and will continue to be key in translating the in vivo complexity into molecular mechanism. This is especially the case since tubulin modifications such as glutamylation have recently been found to be important also for the function of non-tubulin substrates such as the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) or the DNA sensor cGAS [38; 39].

Tubulin Code Writers and Erasers: moving beyond a parts list to understand pattern formation

Most modification enzymes have been known for almost a decade, with the first enzyme identified more than 40 years ago (reviewed in [10*] and [29]). Many catalyze the addition of amino acids (tyrosine, glutamate and glycine) and belong to the tubulin tyrosine ligase (TTL) and TTL-like family (TTLLs) [40]. Glutamylation is the most abundant modification in the nervous system [41]. Not surprising, humans have nine TTLL glutamylases [42]. TTLL7 is most abundant in neurons. Its expression increases steadily during neurogenesis together with β-tubulin glutamylation [43]. The reverse reaction of removing the glutamate chains is catalyzed by a family of carboxypeptidases (CCP1–6; reviewed in [10]* and [29]). So far, it is unclear whether the glycine chains are removed, possibly making this a terminal modification. Many of the TTLL and CCP family members have yet to be studied in mammalian neurons. Thus, this is likely a fertile area of discovery in trying to understand the connection between the tubulin code, neuronal polarity and intracellular trafficking.

The last year has seen a major breakthrough in completing the roster of tubulin code writers: the enzyme that initiates the detyrosination/tyrosination cycle by removing the terminal tyrosine from α-tubulin was identified after a 40-year search [44]. Two groups, one using a high-throughput nonbiased genetic [45]**, the other a chemical proteomics approach [28**] reported that vasohibins (VASH1/2) encode tubulin detyrosination activity. Intriguingly, even though they are found in the cytosol, vasohibins were thought to act in the extracellular environment and inhibit endothelial cell growth in VEGF mediated angiogenesis [44]. In the absence of vasohibins, axonal differentiation is delayed [28**], contrary to the premature axonal differentiation of TTL KO mice [25]. The discovery of the tyrosine carboxypeptidase finally allows genetic manipulation of the detyrosination/tyrosination cycle that was limited until now to the use of inhibitors with limited specificity such as parthenolide [47].

Tubulin is also phosphorylated on multiple residues. The Down Syndrome kinase MNB/DYRK1a was recently found to phosphorylate β-tubulin on Ser172 and inhibit polymerization, consistent with the location of this residue at a polymerization interface. Loss of this kinase disrupts dendrite morphology in Drosophila sensory neurons and causes mechanosensation defects [48**]. Interestingly, DYRK1a uses the C-terminal tails of tubulin to anchor to the microtubule, raising the intriguing possibility that it can be sensitive to their posttranslational status, thus establishing a hierarchy of modification by tubulin modification enzymes. Similarly, the glutamylase TTLL7 is dependent on its interaction with the α-tubulin tail to modify the β-tubulin tail [49], hinting at a possible syntax of tubulin modifications on the microtubule.

As the major tubulin code writers are now known the challenge will be to understand how the code is laid out during development and then maintained and modulated by environmental cues and synaptic activity. As the combinatorial action of modification enzymes is responsible for the complex microtubule modification patterns observed in cells, we will need to understand their kinetic properties, subcellular localization, substrate specificity and identify cellular regulators. At the most basic level, patterns of modifications can be controlled by direct competition for common modification sites, as is the case for glutamylation and glycylation [50]. Kinetic control i.e., the intersection between the dynamic parameters of microtubules (which can have turnover rates ranging from seconds to minutes or hours in cells) with the catalytic rate of the modification enzymes can give rise to different modification profiles on microtubules that are in close spatial proximity and thus is likely an important mechanism for establishing complex spatial patterns. How tubulin modification enzymes are targeted, activated or inhibited is largely unknown and will be an essential area of exploration in the future. Notably, synaptic activity was correlated with an increase in microtubule polyglutamylation that affected the mobility of a subset of kinesin-1 cargo complexes [51], thus placing a tubulin code writer downstream of an activity dependent signaling cascade and suggesting a possible involvement of the tubulin code in synaptic tagging.

Effects of posttranslational modifications on microtubule properties

In addition to regulation in trans, posttranslational modifications can also affect intrinsic polymer properties. Modifications found in the axon (detyrosination, glutamylation, acetylation and polyamination) are associated with stability as microtubules with these modifications persist for several hours and are resistant to drug or cold induced depolymerization. The mechanistic basis for this differential stability is not understood: are the modifications affecting polymer stability directly or indirectly through the recruitment of effectors? Intriguingly, the catalytic rates of the enzymes that tyrosinate, glutamylate and acetylate the tubulin substrate match the lifetime of these microtubule populations. TTL has the fastest catalytic rate [52] of the modification enzymes studied so far, the TTLL7 glutamylase has an intermediate rate [49] while the acetyltransferase (TAT) has a catalytic rate on the orders of hours [53; 54]. For acetylation, this slow catalytic rate was proposed to function as a clock for microtubule lifetimes as only stable microtubule would persist long enough to be robustly acetylated [54]. Interestingly, recent work revealed that acetylation on lumenal Lys40 has a direct effect on the microtubule: it weakens lateral interactions between protofilaments, thus increasing depolymerization rates and decreasing nucleation. This loss of lateral stabilization renders the lattice more resistant against damage produced by buckling forces [55*] and protects microtubules in cells against rupture due to mechanical stress [56**], a useful property to leverage in axons. Consistent with this, the microtubule network in sensory neurons of TAT KO mice is less elastic leading to a higher threshold for channel activation and loss in mechanosensitivity [57**]. Thus, both biochemical and in vivo data demonstrate a role for acetylation in changing the mechanical properties of the microtubule. What still remains puzzling is the kinetics of this change in mechanical stability. TAT is a very slow enzyme, suggesting that the microtubule would have to be initially stabilized against depolymerization through a different mechanism in order to persist long enough to be a substrate for TAT. The effects of glutamylation and detyrosination on both microtubule dynamics and mechanics remain to be characterized. Glutamylation is especially interesting as it can add both significant bulk and negative charge to the tubulin tails known to affect polymerization [58].

Conclusions and Future Directions

More than any other cell type, the neuron needs to establish a non-isotropic organization of its microtubule cytoskeleton. It achieves this both by controlling geometry (polarity and organization in bundles) and chemical composition (tubulin isoforms and posttranslational modifications). The ongoing revolution in high-resolution microscopy combined with labeling tools that still need to be developed (live reporters for tubulin modifications, fluorescent amino acid analogs that can serve as substrates for engineered modification enzymes and reporters that can sense numbers of glutamates added to the tubulin tails) will get us closer to constructing high-resolution dynamic maps of tubulin posttranslational modifications in the neuron. This topographical information combined with functional information on the recruitment and activity of cellular effectors and eventually simultaneous readout of synaptic activity will allow us to fully explore the raison d’être of the tubulin code in the nervous system. Given the strong involvement of tubulin mutations and tubulin code enzymes in disease, breaking the tubulin code can potentially bring translational benefits in the form of improved diagnostics and therapeutics.

Highlights.

Isoforms and posttranslational modifications generate the tubulin code for neuronal polarization.

Tubulin isoforms have distinct properties and functions.

Tubulin posttranslational modifications modulate microtubule intrinsic properties and effectors.

New tools open a new chapter in the molecular dissection of the tubulin code.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erina He (National Institute of Health Medical Arts) for help with illustration.

Funding

A.R.M. is supported by the intramural programs of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. J.H.P. is a clinical fellow supported by the Office of the Clinical Director, National Institute of Neurological Disorders.

Abbreviations

- CCP

Cytosolic carboxypeptidase

- FIB-SEM

Focused ion beam-scanning electron microscopy

- MAP

Microtubule-associated protein

- PTM

Posttranslational modification

- SVBP

Small vasohibin binding protein

- TTL

Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase

- TTLL

Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase-Like

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VASH

Vasohibin

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of special interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

*of interest

**of outstanding interest

- 1.Gundersen GG, Kreitzer G, Cook T, Liao G: Microtubules as determinants of cellular polarity. Biol Bull 1998, 194:358–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.*.Yu I, Garnham CP, Roll-Mecak A: Writing and Reading the Tubulin Code. J Biol Chem 2015, 290:17163–17172.Recent review on tubulin post-translational modifications.

- 3.Wilson PG, Borisy GG: Evolution of the multi-tubulin hypothesis. Bioessays 1997, 19:451–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verhey KJ, Gaertig J: The tubulin code. Cell Cycle 2007, 6:2152–2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coles CH, Bradke F: Coordinating Neuronal Actin–Microtubule Dynamics. Curr Biol 2015, 25:R677–R691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janke C, Kneussel M: Tubulin post-translational modifications: encoding functions on the neuronal microtubule cytoskeleton. Trends Neurosci 2010, 33:362–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robson SJ, Burgoyne RD: Differential localisation of tyrosinated, detyrosinated, and acetylated α-tubulins in neurites and growth cones of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 1989, 12:273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond JW, Huang C-F, Kaech S, Jacobson C, Banker G, Verhey KJ: Posttranslational modifications of tubulin and the polarized transport of kinesin-1 in neurons. Mol Biol Cell 2010, 21:572–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.**.Tas RP, Chazeau A, Cloin BMC, Lambers MLA, Hoogenraad CC, Kapitein LC: Differentiation between Oppositely Oriented Microtubules Controls Polarized Neuronal Transport. Neuron 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.018.Introduces a super-resolution imaging technique, motor-PAINT and shows that dendritic microtubule bundles of opposite orientation differ in stability and composition and recruit different motor proteins. Minus-end out microtubule bundles are acetylated while plus-end ones are tyrosinated, resulting in the selective targeting of kinesin-1 to acetylated microtubules in the axon.

- 10.*.Song Y, Brady ST: Post-translational modifications of tubulin: pathways to functional diversity of microtubules. Trends Cell Biol 2015, 25:125–136.Recent review on tubulin post-translational modifications.

- 11.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, et al. : Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347:1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.**.Vemu A, Atherton J, Spector JO, Moores CA, Roll-Mecak A: Tubulin isoform composition tunes microtubule dynamics. Mol Biol Cell 2017, 28:3564–3572.Shows that microtubules with different tubulin isoforms compositions have different dynamic parameters and reports the 4.2Å cryo-EM structure of a microtubule composed of α1B/βI+βIVb tubulin. Also shows that the dynamic parameters of non-neuronal α1B/βI+βIVb microtubules can be proportionally tuned by the addition of neuronal α1A/βIII tubulin isoform with different dynamic properties.

- 13.Itzhak DN, Tyanova S, Cox J, Borner GH: Global, quantitative and dynamic mapping of protein subcellular localization. Elife 2016, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tischfield MA, Engle EC: Distinct α-and β-tubulin isotypes are required for the positioning, differentiation and survival of neurons: new support for the “multi-tubulin”hypothesis. Biosci Rep 2010, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saillour Y, Broix L, Bruel-Jungerman E, Lebrun N, Muraca G, Rucci J, Poirier K, Belvindrah R, Francis F, Chelly J: Beta tubulin isoforms are not interchangeable for rescuing impaired radial migration due to Tubb3 knockdown. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23:1516–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsetos CD, Herman MM, Mörk SJ: Class III β‐tubulin in human development and cancer. Cytoskeleton 2003, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgoyne RD, Cambray-Deakin MA, Lewis SA, Sarkar S, Cowan NJ: Differential distribution of beta-tubulin isotypes in cerebellum. EMBO J 1988, 7:2311–2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preitner N, Quan J, Nowakowski DW, Hancock ML, Shi J, Tcherkezian J, Young-Pearse TL, Flanagan JG: APC is an RNA-binding protein, and its interactome provides a link to neural development and microtubule assembly. Cell 2014, 158:368–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minoura I, Hachikubo Y, Yamakita Y, Takazaki H, Ayukawa R, Uchimura S, Muto E: Overexpression, purification, and functional analysis of recombinant human tubulin dimer. FEBS Lett 2013, 587:3450–3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.*.Vemu A, Atherton J, Spector JO, Szyk A, Moores CA, Roll-Mecak A: Structure and Dynamics of Single-isoform Recombinant Neuronal Human Tubulin. J Biol Chem 2016, 291:12907–12915.Reports the first purification, dynamic parameters and high-resolution cryo-EM structure of recombinant isotypically-pure neuronal α1A/βIII microtubules with no affinity tags at the tubulin C-termini.

- 21.Widlund PO, Podolski M, Reber S, Alper J, Storch M, Hyman AA, Howard J, Drechsel DN: One-step purification of assembly-competent tubulin from diverse eukaryotic sources. Mol Biol Cell 2012, 23:4393–4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.**.Pamula MC, Ti S-C, Kapoor TM: The structured core of human β tubulin confers isotype-specific polymerization properties. J Cell Biol 2016, 213:425–433.Uses recombinant purified β-tubulin isoforms to show that sequence differences in the structured core of human βIIB tubulin and not the disordered tails are responsible for a lower catastrophe frequency compared to neuronal βIII.

- 23.Silva M, Morsci N, Nguyen KCQ, Rizvi A, Rongo C, Hall DH, Barr MM: Cell-Specific α-Tubulin Isotype Regulates Ciliary Microtubule Ultrastructure, Intraflagellar Transport, and Extracellular Vesicle Biology. Curr Biol 2017, 27:968–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Vos KJ, Grierson AJ, Ackerley S, Miller CCJ: Role of Axonal Transport in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Annu Rev Neurosci 2008, 31:151–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erck C, Peris L, Andrieux A, Meissirel C, Gruber AD, Vernet M, Schweitzer A, Saoudi Y, Pointu H, Bosc C, et al. : A vital role of tubulin-tyrosine-ligase for neuronal organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102:7853–7858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikegami K, Sato S, Nakamura K, Ostrowski LE, Setou M: Tubulin polyglutamylation is essential for airway ciliary function through the regulation of beating asymmetry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107:10490–10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogowski K1, van Dijk J, Magiera MM, Bosc C, Deloulme JC, Bosson A, Peris L, Gold ND, Lacroix B, Bosch Grau M, et al. : A family of protein-deglutamylating enzymes associated with neurodegeneration. Cell 2010, 143(4):564–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.**.Aillaud C, Bosc C, Peris L, Bosson A, Heemeryck P, Van Dijk J, Le Friec J, Boulan B, Vossier F, Sanman LE, et al. : Vasohibins/SVBP are tubulin carboxypeptidases (TCP) that regulate neuron differentiation. Science 2017, doi: 10.1126/science.aao4165.Identifies the long-sought tubulin detyrosinase as the VASH1/2-SVBP complex using an unbiased chemical proteomics high-throughput approach. Knock down of vasohibins impairs neuronal differentiation in vitro and disrupts neuronal migration in the developing mouse neocortex.

- 29.Garnham CP, Roll-Mecak A: The chemical complexity of cellular microtubules: tubulin post-translational modification enzymes and their roles in tuning microtubule functions. Cytoskeleton 2012, 69:442–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.**.Nirschl JJ, Magiera MM, Lazarus JE, Janke C, Holzbaur ELF: α-Tubulin Tyrosination and CLIP-170 Phosphorylation Regulate the Initiation of Dynein-Driven Transport in Neurons. Cell Rep 2016, 14:2637–2652.Shows that the α-tubulin tyrosination gradient in the axon and CLIP-170 phosphorylation initiates retrograde transport at the distal axon, through an elegant combination of in vitro reconstitution assays with tyrosinated and detyrosinated microtubules, live-cell imaging of cultured neurons, and computer simulations.

- 31.*.McKenney RJ, Huynh W, Vale RD, Sirajuddin M: Tyrosination of α‐tubulin controls the initiation of processive dynein–dynactin motility. EMBO J 2016, 35:1175–1185.Shows tyrosinated tubulin recruits dynein/dynactin and initiates processive retrograde dynein/dynactin motility through a specific interaction between the CAP-Gly domain of p150 with the C-terminal tyrosine of α-tubulin using in vitro motility assays with engineered S. cerevisae tubulin. Once motility is initiated, the C-terminal tyrosine is not needed for processive movement.

- 32.Roll-Mecak A, McNally FJ: Microtubule-severing enzymes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2010, 22:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.**.Valenstein ML, Roll-Mecak A: Graded Control of Microtubule Severing by Tubulin Glutamylation. Cell 2016, 164:911–921.Introduces a biochemical platform to examine the effects of tubulin post-translational modifications and shows that glutamylation is the main regulator of the hereditary spastic paraplegia microtubule severing enzyme spastin and that neither detyrosination nor acetylation regulate spastin activity. Glutamylation tunes microtubule severing as a function of glutamate number added per tubulin, providing the first evidence for a precise graded response to a tubulin polymodification.

- 34.Redeker V: Mass spectrometry analysis of C-terminal posttranslational modifications of tubulins. Methods Cell Biol 2010, 95:77–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dehmelt L, Halpain S: The MAP2/Tau family of microtubule-associated proteins. Genome Biol 2005, 6:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonnet C, Boucher D, Lazereg S, Pedrotti B, Islam K, Denoulet P, Larcher JC: Differential binding regulation of microtubule-associated proteins MAP1A, MAP1B, and MAP2 by tubulin polyglutamylation. J Biol Chem 2001, 276:12839–12848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sirajuddin M, Rice LM, Vale RD: Regulation of microtubule motors by tubulin isotypes and post-translational modifications. Nat Cell Biol 2014, 16:335–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun X, Park J, Gumerson J, Wu Z, Swaroop A, Qian H, Roll-Mecak A and Li T Loss of RPGR glutamylation underlies pathogenic mechanism of retinal dystrophy caused by TTLL5 mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2016. 13(21):E2925–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia P, Ye B, Wang A, Zhu X, Du Y, Xiong A, Tian Y and Fan Z Glutamylation of the DNA sensor cGAS regulates its binding and synthase activity in antiviral immunity. Nature Immunol. 2016. 17(4):369–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janke C, Rogowski K, Wloga D, Regnard C, Kajava AV, Strub J-M, Temurak N, van Dijk J, Boucher D, van Dorsselaer A, et al. : Tubulin polyglutamylase enzymes are members of the TTL domain protein family. Science 2005, 308:1758–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Redeker V, Rossier J, Frankfurter A: Posttranslational modifications of the C-terminus of alpha-tubulin in adult rat brain: alpha 4 is glutamylated at two residues. Biochemistry 1998, 37:14838–14844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Dijk J, Rogowski K, Miro J, Lacroix B, Eddé B, Janke C: A targeted multienzyme mechanism for selective microtubule polyglutamylation. Mol Cell 2007, 26:437–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikegami K, Mukai M, Tsuchida J-I, Heier RL, Macgregor GR, Setou M: TTLL7 is a mammalian beta-tubulin polyglutamylase required for growth of MAP2-positive neurites. J Biol Chem 2006, 281:30707–30716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barra HS, Arce CA, Argaraña CE: Posttranslational tyrosination/detyrosination of tubulin. Mol Neurobiol 1988, 2:133–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.**.Nieuwenhuis J, Adamopoulos A, Bleijerveld OB, Mazouzi A, Stickel E, Celie P, Altelaar M, Knipscheer P, Perrakis A, Blomen VA, et al. : Vasohibins encode tubulin detyrosinating activity. Science 2017,Reports the use of an unbiased high-throughput genetics approach to identify the long-sought tubulin detyrosinase as a complex between vasohibin1/2 and the small peptide SVBP. Demonstrates that the vasohibins recognize specifically the C-terminal tyrosine in the α-tubulin tail.

- 46.Kimura H, Miyashita H, Suzuki Y, Kobayashi M, Watanabe K, Sonoda H, Ohta H, Fujiwara T, Shimosegawa T, Sato Y: Distinctive localization and opposed roles of vasohibin-1 and vasohibin-2 in the regulation of angiogenesis. Blood 2009, 113:4810–4818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fonrose X, Ausseil F, Soleilhac E, Masson V, David B, Pouny I, Cintrat J-C, Rousseau B, Barette C, Massiot G, et al. : Parthenolide inhibits tubulin carboxypeptidase activity. Cancer Res 2007, 67:3371–3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.**.Ori-McKenney KM, McKenney RJ, Huang HH, Li T, Meltzer S, Jan LY, Vale RD, Wiita AP, Jan YN: Phosphorylation of β-Tubulin by the Down Syndrome Kinase, Minibrain/DYRK1a, Regulates Microtubule Dynamics and Dendrite Morphogenesis. Neuron 2016, 90:551–563.Reports that Minibrain (MNB)/DYRK1a, a kinase implicated in Down syndrome and autism spectrum disorders, phosphorylates β-tubulin on Ser172 and inhibits tubulin polymerization. Loss of Minibrain perturbs dendritic morphology and electrophysiological function leading to arborization defects.

- 49.Garnham CP, Vemu A, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Yu I, Szyk A, Lander GC, Milligan RA, Roll-Mecak A: Multivalent Microtubule Recognition by Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase-like Family Glutamylases. Cell 2015, 161:1112–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garnham CP, Yu I, Li Y, Roll-Mecak A: Crystal structure of tubulin tyrosine ligase-like 3 reveals essential architectural elements unique to tubulin monoglycylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114:6545–6550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maas C, Belgardt D, Lee HK, Heisler FF, Lappe-Siefke C, Magiera MM, van Dijk J, Hausrat TJ, Janke C, Kneussel M: Synaptic activation modifies microtubules underlying transport of postsynaptic cargo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106:8731–8736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szyk A, Deaconescu AM, Piszczek G, Roll-Mecak A: Tubulin tyrosine ligase structure reveals adaptation of an ancient fold to bind and modify tubulin. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011, 18:1250–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shida T, Cueva JG, Xu Z, Goodman MB, Nachury MV: The major α-tubulin K40 acetyltransferase αTAT1 promotes rapid ciliogenesis and efficient mechanosensation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107:21517–21522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szyk A, Deaconescu AM, Spector J, Goodman B, Valenstein ML, Ziolkowska NE, Kormendi V, Grigorieff N, Roll-Mecak A: Molecular basis for age-dependent microtubule acetylation by tubulin acetyltransferase. Cell 2014, 157:1405–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.*.Portran D, Schaedel L, Xu Z, Théry M, Nachury MV: Tubulin acetylation protects long-lived microtubules against mechanical ageing. Nat Cell Biol 2017, 19:391–398.Uses a FRET assay to show that acetylation by TAT decreases the strength of lateral interactions in the microtubule lattice, resulting in reduced nucleation and faster depolymerization rates. Using an in vitro bending assay reports that acetylation reduces the microtubule persistence length. The authors propose that this increase in plasticity with acetylation is facilitated by easier sliding of the protofilaments in microtubules under mechanical stress.

- 56.**.Xu Z, Schaedel L, Portran D, Aguilar A, Gaillard J, Marinkovich MP, Théry M, Nachury MV: Microtubules acquire resistance from mechanical breakage through intralumenal acetylation. Science 2017, 356:328–332.Reports that acetylation by TAT is required for mechanical stabilization of long-lived microtubules in fibroblasts. In vitro bending assays show that acetylation protects microtubules against mechanical rupture by making them more flexible.

- 57.**.Morley SJ, Qi Y, Iovino L, Andolfi L, Guo D, Kalebic N, Castaldi L, Tischer C, Portulano C, Bolasco G, et al. : Acetylated tubulin is essential for touch sensation in mice. Elife 2016, 5.Reports the existence of a band of acetylated microtubules under the membrane of sensory neurons in cell bodies and axons. Using a tubulin acetyltransferase (Atat1) conditional KO mouse with deleted Atat1 from peripheral neurons the authors demonstrate that Atat1 dependent loss of acetylation reduces cellular elasticity at the sub-membrane of dorsal root ganglion cells and lowers the threshold of mechanosensitive ion channel opening, thus modulating mechanosensation in mice.

- 58.Sackett DL, Bhattacharyya B, Wolff J: Tubulin subunit carboxyl termini determine polymerization efficiency. J Biol Chem 1985, 260:43–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]