Abstract

We aimed to estimate the utility of panel‐based pharmacogenetic testing of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Utilization of Clinical Pharmacogenetic Implementation Consortium (CPIC) level A/B drugs after PCI was estimated in a national sample of IBM MarketScan beneficiaries. Genotype data from University of Florida (UF) patients (n = 211) who underwent PCI were used to project genotype‐guided opportunities among MarketScan beneficiaries with at least one (N = 105,547) and five (N = 12,462) years of follow‐up data. The actual incidence of genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities was determined among UF patients. In MarketScan, 50.0% (52,799/105,547) over 1 year and 68.0% (8,473/12,462) over 5 years had ≥ 1 CPIC A/B drug besides antiplatelet therapy prescribed, with a projected incidence of genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities of 39% at 1 year and 52% at 5 years. Genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities occurred in 32% of UF patients. Projected and actual incidence of genotype‐guided opportunities among two cohorts supports the utility of panel‐based testing among patients who underwent PCI.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

☑ Reactive genotype testing is the most common model for pharmacogenetic implementation.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

☑ Demonstrate the clinical utility of preemptive, panel‐based testing among patients with post‐percutaneous coronary intervention to guide pharmacogenetic drug prescribing beyond cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 19 (CYP2C19) testing.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

☑ Data from two cohorts of patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within MarketScan and University of Florida Health Precision Medicine Program demonstrate a high prevalence of pharmacogenetic drugs and actionable genotypes among patients who undergo PCI.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE

☑ Pre‐emptive, panel‐based testing at the time of PCI could lead to genotype‐guided prescribing decisions in over a third of patients, improving drug therapy outcomes beyond CYP2C19 testing for antiplatelet therapy selection.

Pharmacogenetics offers the potential to improve patient outcomes and drug safety through genotype‐guided approaches.1 Implementation efforts span from testing for a single gene at the time of drug prescribing (i.e., reactive testing model) to testing for multiple genes as part of a pharmacogenetics panel ahead of the need for drug therapy (i.e., preemptive, multipharmacogene, and panel‐based testing model). Although the latter may offer efficiencies, only the former is currently reimbursed by third party payers.2

A major barrier with a reactive testing model is the genotype turnaround time, which may affect clinical adoption of pharmacogenetics and widespread uptake in diverse health systems. Specifically, delays in turnaround time can lead to unavailability of genotype information at the time of prescribing. Clinicians would need to follow‐up with patients after genotype results are returned if results dictate a change in therapy. This can negatively impact work flow.3 Pre‐emptive pharmacogene panel‐based testing, on the other hand, may represent a more efficient model for pharmacogenetics implementation4 as it allows for the availability of genotype data at the time of prescribing for multiple medications.

Opponents of a preemptive approach argue that it may lead to unnecessary genotyping for drugs to which patients may never be exposed.4 Previous studies in general patient populations have reported a high prevalence of exposure to medications for which there is strong evidence for genetic associations with adverse events or clinical benefits.5, 6 However, no study has focused such estimates on a concrete example of patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). PCI is one of the most common clinical scenarios in which pharmacogenetic testing occurs7, 8 and for which testing is covered by most insurance plans. Additionally, patients who undergo PCI are considered high‐risk patients who are characterized by polypharmacy.9 Thus, preemptive testing for gene‐drug pairs that are frequently prescribed to this patient population may be cost‐effective.

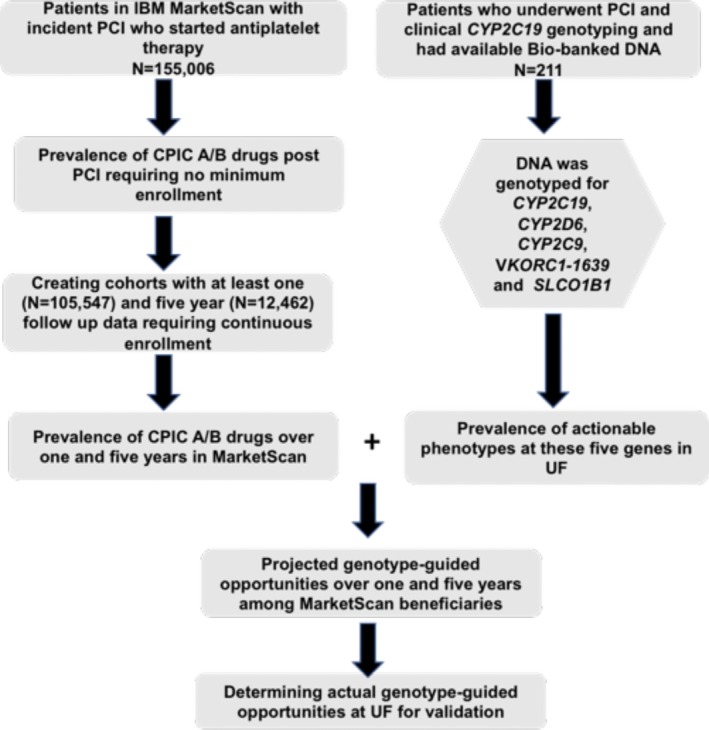

We aimed to estimate opportunities for genotype‐guided prescribing, beyond cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 19 (CYP2C19)‐guided antiplatelet prescribing, following pharmacogene panel‐based testing at the time of PCI. To accomplish this aim, a large claims database representative of commercially insured patients in the United States was utilized to identify prevalence of pharmacogenetic medications, with a focus on patients who underwent PCI. Information on pharmacogenetic variants and prescription of pharmacogenetic medications were assessed in a second cohort of patients who underwent PCI and clinical CYP2C19 genotyping as part of the Precision Medicine Program at the University of Florida Health (UF). The design of the study is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study design outline. CPIC, Clinical Pharmacogenetic Implementation Consortium; CYP2C9, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9; CYP2C19, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 19; CYP2D6, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily D member 6; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SLCO1B1, solute carrier organic anion transporter family 1B1; UF, University of Florida; VKORC1, vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1.

Materials and methods

IBM MarketScan cohort

Using IBM MarketScan Commercial claims data from 2008–2015, we created a cohort of patients who underwent PCI. Patients 18–64 years old were included in the analysis if they had at least 6 months of continuous enrollment in a health plan prior to the first identified PCI. We defined an index PCI as any inpatient or outpatient encounter claim for PCI identified through current procedural terminology codes or International Classification of Diseases–Ninth Revision procedure codes (Table S1 ), in addition to a pharmacy dispensing claim for clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor within 7 days of PCI. Although among antiplatelet therapies only clopidogrel is influenced by CYP2C19, the initiation of prasugrel or ticagrelor may have been a direct result of CYP2C19 testing. Thus, initiators of any of the three antiplatelet agents were included. To identify the most frequently prescribed pharmacogenetic medications in addition to antiplatelet regimens among patients who underwent PCI, we estimated the prevalence of additional drugs with a high level of evidence supporting genotype‐guided prescribing, using pharmacy billing records. We defined such pharmacogenetic drugs (Table S2 ) as having Clinical Pharmacogenetic Implementation Consortium (CPIC) level A/B evidence (Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase evidence 1A through 2A, whose effects are modified by genotypes at CYP2C19, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily D member 6 (CYP2D6), cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9 (CYP2C9), vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 (VKORC1), or solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1 (SLCO1B1)). We focused on these genes because they are most often captured on the pharmacogenetics panels.10

The assessed drugs (CPIC level A/B) included those with current CPIC guidance or significant literature supporting genetic associations with response, some which are under CPIC consideration (e.g., proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)11 and celecoxib). Only drugs prescribed after initiation of any of the three antiplatelet agents were assessed.

First, we determined the prevalence of additional pharmacogenetic drugs among beneficiaries, without requiring a minimum length of health plan enrollment. These data are expected to inform payers about the prevalence of pharmacogenetic drugs among beneficiaries regardless of the length of coverage. Second, we created cohorts of varying periods of continuous plan enrollment (1 year through 5 years), in whom we determined annual or multi‐annual prevalence of CPIC level A and CPIC level A or B drug use. We specifically used the drug prevalence data over 1 year and 5 years for patients who survived throughout the follow‐up period and had at least 1 year (N = 105,547) and 5 years (N = 12,462) of follow‐up data, to project the short‐term and long‐term utility of preemptive genotyping, regardless of switches in health plans (Figure 1).

UF Health Personalized Medicine Program PCI cohort

In 2012, the Precision Medicine Program at UF Health Shands Hospital initiated CYP2C19 testing for patients at the time of left heart catheterization (LHC), anticipating that many of these patients would proceed to PCI and require a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor.12 Testing was expanded to UF Health in Jacksonville in 2016, which also focused on patients undergoing LHC with intent for PCI.13 For the purpose of this study, we included 211 patients (mean age 65 ± 11 years) who were genotyped for CYP2C19, underwent PCI, and consented to storage of their excess blood samples for DNA biobanking and future research14 (Figure 1).

Genotyping methods

Genomic DNA from the 211 UF Health patients was isolated using FlexiGene DNA Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to kit manufacturer instructions and genotyped using a fluorescence‐based TaqMan OpenArray QuantStudio RealTime PCR System15 (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Boston, MA, USA) for common genetic variants in CYP2C19, CYP2D6, SLCO1B1, CYP2C9, and VKORC1 (Table 1). Only single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and not copy number variation or gene deletion (CYP2D6*5) were determined, precluding the evaluation of CYP2D6 ultra‐rapid metabolizer (UM), and reducing the prevalence of CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizer (IM) and poor metabolizer (PM) phenotype status. Genotyping accuracy for SNPs in CYP2C19, CYP2C9, VKORC1, and SLCO1B1 was validated against the high resolution melting methodology, in which genotyping concordance was documented to range between 99.1% and 100%.15 To ascertain the validity of CYP2D6 genotyping, 60 samples were randomly selected for pyrosequencing (PSQ HS 96; Qiagen) for *4, *10, *17, and *41 variants,16 for which 100% genotype concordance was observed. All samples (n = 211) were successfully genotyped for SNPs of interest in the five genes.

Table 1.

SNPs genotyped in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention at UF Health and consented to DNA biobanking

| Gene | SNPs |

|---|---|

| CYP2C19 | *2 (c.681G>A, rs4244285) |

| *3 (c.636G>A, rs4986893) | |

| *4 (c.1A>G, rs28399504) | |

| *6 (c.395G>A, rs72552267) | |

| *8 (c.358T>C, rs41291556) | |

| *17 (c.‐806C>T, rs12248560) | |

| SLCO1B1 | *5 (c.521T>C, rs4149056) |

| CYP2C9 | *2 (c.430C>T, rs1799853) |

| *3 (c.1075A>C, rs1057910) | |

| *5 (c.1080C>G, rs28371686) | |

| *8 (c.449G>A, rs7900194) | |

| *11 (c.1003C>T, rs28371685) | |

| *14 (c.374G>A, rs72558189) | |

| VKORC1 | ‐1639G>A (rs992323) |

| CYP2D6 | *2 (c.886C>T, rs16947); (c.1457G>C, rs1135840) |

| *3 (c.775delA, rs35742686) | |

| *4 (c.506‐1G>A, rs3892097) | |

| *6 (c.363‐141delT, rs5030655) | |

| *10 (c.100C>T, rs1065852) | |

| *17 (c.320C>T, rs28371706) | |

| *41 (c.841 + 39G>A, rs28371725) |

CYP2C9, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9; CYP2C19, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 19; CYP2D6, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily D member 6; SLCO1B1, solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1; SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms; UF, University of Florida; VKORC1, vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1.

The study component related to the UF Health Precision Medicine Program was approved by the UF Institutional Review Board, whereas the MarketScan‐related analysis was deemed exempt by the UF Institutional Review Board because of the use of de‐identified data.

Definition of actionable genotypes/phenotypes

The star diplotype nomenclature was assigned for the assessed CYP450 gene using the translation tables from the PharmGKB website.17 We evaluated whether a genotype was actionable based on an understanding of its effect on drug response phenotype, consistent with the approach adopted by CPIC.18 A gene‐drug pair was considered “actionable” if the genotype would influence selection of a drug or drug dose, and, thus, was assigned specific recommendations/guidance from CPIC. For drugs with CPIC level B evidence, for which CPIC guidelines are in process (e.g., PPIs and celecoxib, personal communication from CPIC), we defined actionable genotypes according to available literature and/or other professional guidelines such as those put forward by the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group.19, 20 A similar approach was taken for drugs meeting evidence‐level criteria for inclusion but with no current CPIC guidelines (risperidone and venlafaxine).

The term “actionable phenotype” was dependent on the evaluated gene‐drug pair. For example, CYP2C19 UM, rapid metabolizer, and PM phenotypes were considered “actionable” for tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine, and doxepin), PPIs, and certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (citalopram and escitalopram).21 However, only the CYP2C19 PM phenotype was considered “actionable” for sertraline per CPIC guidance.21, 22 For warfarin, we evaluated the combination of both CYP2C9 diplotypes and VKORC1‐1639 c.G>A (rs992323) to determine warfarin sensitivity phenotypes.23 For example, a highly sensitive warfarin was defined as a combination of VKORC1 rs9923231 AA plus CYP2C9 *1/*3, *2/*2, *2/*3, or *3/*3; VKORC1 rs9923231 GG plus CYP2C9 *3/*3, or VKORC1 rs9923231 AG plus CYP2C9 *3/*3 or *2/*3. A sensitive warfarin was defined as VKORC1 rs9923231 GG plus CYP2C9 *1/*3; VKORC1 rs9923231 AG plus a CYP2C9 heterozygote genotype (e.g., *1/*3 and *1/*2), or homozygote CYP2C9 variant genotype (*2/*2), or compound CYP2C9 heterozygote (*2/*3).

We assessed opioids that met the criterion for inclusion (CPIC level A) or are not considered good alternatives for patients with CYP2D6 IM/PM phenotypes (codeine, oxycodone, and tramadol).24 Although CYP2D6 UM phenotype status is considered “actionable” for some drugs, such as opioids and ondansetron, it was not assessed in our study because we did not quantify copy number variants.

For each patient, the number of actionable phenotypes was determined based on their diplotypes at CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, SLCO1B1, and combination of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 (warfarin sensitivity). For example, if a patient had a CYP2C19*17/*17, CYP2D6*1/*1, VKORC1 ‐1639AA, CYP2C9*2/*3, and SLCO1B1*5, then this patient would be considered actionable for four phenotypes (CYP2C19 UM, CYP2C9 PM, warfarin high sensitivity, and risk of muscle toxicity).

Projection of genotype‐guided drug prescribing decisions following PCI using 1 year and 5 year drug prevalence data (MarketScan) and prevalence of actionable phenotypes (UF)

Following PCI and antiplatelet initiation, we estimated the 1‐year and 5‐year genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities (excluding the initial decision regarding CYP2C19‐guided antiplatelet therapy). The projected genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities were calculated by considering the 5 evaluated genes in the UF PCI cohort (Table 1) and 30 pharmacogenetic drugs (Table S3 ). Additionally, gene‐drug pairs that are influenced by CYP2D6 UM were not included. The prevalence of each actionable phenotype (derived from UF data) was multiplied by the 1‐year and 5‐year post‐PCI prevalence data of the corresponding medication (determined from MarketScan) to calculate the projected 1 year and 5 year's genotype‐guided prescribing opportunity, respectively.

To contrast drug utilization data from our national sample (MarketScan) with our UF population (which provided the phenotype prevalence), we extracted 1‐year post‐PCI inpatient and outpatient prescriptions from UF electronic health records. As a validation for our projections in MarketScan, we defined the actual genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities in UF as the percentage of patients with actionable phenotypes who were prescribed the relevant pharmacogenetic drug(s).

Results

Prevalence of actionable phenotypes in UF patients who underwent PCI

The average age of the UF patient cohort (N = 211) was 65 ± 11 years; 46% were white, 48% were African American, 1% were Asians, and 5% were multiracial or of unknown race. The genotype/phenotype prevalence is summarized in Table 2. Seventy‐seven percent of UF patients had at least one actionable phenotype for the evaluated genes; 56% for CYP2C19, 5% for CYP2D6, 25% for CYP2C9, 22% for the combination of VKORC1/CYP2C9 (warfarin sensitivity), and 15% for SLCO1B1.

Table 2.

Prevalence of actionable phenotypes for five genes among patients with PCI at the UF (N = 211)

| Gene | Phenotypes | Example genotypes | Prevalence of actionable phenotypes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C19 | RM/UM | *1/*17; *17/*17 | 33.2 |

| IM | *1/*2; *1/*3; *1/*8 | 19.9 | |

| PM | *2/*2; 2/*3 | 2.4 | |

| Provisional IMa | *2/*17 | 7.6 | |

| CYP2D6 | IM | *4/*41; *4/10; *4/*17 | 3.3 |

| PM | *4/*6; *4/*4; *3/*4 | 1.9 | |

| CYP2C9 | IM | *1/*2; *1/*3; *1/*5; *1/*8; *1/*11 | 23.2 |

| PM | *2/*2; *2/*3; 3/*3 | 1.4 | |

| VKORC1 + CYP2C9 | Highly warfarin sensitiveb | VKORC1 AG + CYP2C9 *2/*3; VKORC1 AA + CYP2C9 *1/*3 | 1.42 |

| Warfarin sensitivec | VKORC1 GG + CYP2C9 *2/*3; VKORC1 AG + CYP2C9 *1/*2 | 20.4 | |

| SLCO1B1 | Intermediate transporter functiond | rs4149056 CT | 12.8 |

| Low transporter functiond | rs4149056 CC | 1.9 |

CYP2C9, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9; CYP2C19, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 19; CYP2D6, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily D member 6; IM, intermediate metabolizer; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PM, poor metabolizer; RM, rapid metabolizer; SLCO1B1, solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1; UF, University of Florida; UM, ultra‐rapid metabolizer; VKORC1, vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1.

aThe actionable phenotype for CYP2C19 *2/*17 is a provisional classification. b Highly warfarin sensitive: VKORC1 rs9923231 AA plus CYP2C9 *1/*3, *2/*2, *2/*3, or *3/*3; VKORC1 rs9923231 GG plus CYP2C9 *3/*3, VKORC1 rs9923231 AG plus CYP2C9 *3/*3 or *2/*3. cSensitive warfarin: VKORC1 rs9923231 GG plus CYP2C9 *1/*3; VKORC1 rs9923231 AG plus a CYP2C9 heterozygote genotype (e.g., *1/*3 and *1/*2), homozygote CYP2C9 variant genotype (*2/*2), or compound CYP2C9 heterozygote (*2/*3). dBoth intermediate and low transporter function are risk phenotypes for muscle toxicities.

Prevalence of medications with pharmacogenetic guidance in MarketScan

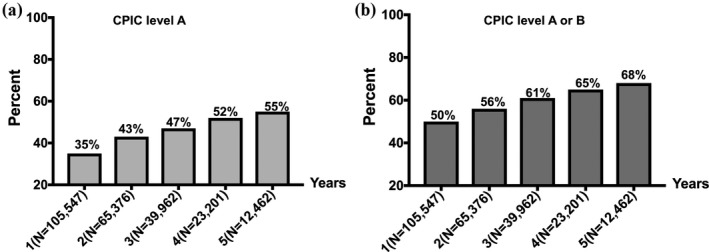

Within the MarketScan database, 155,006 patients had a PCI and were prescribed clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor, whereby no minimum continuous enrollment period after PCI was required. Patients had a total of 312,031 patient‐years of follow‐up during which 44,331 (28.6%) were prescribed at least 1 additional drug with CPIC level A evidence, and 62,157 (40.1%) were prescribed at least 1 additional drug with CPIC level A or B evidence. The prevalence of dispensed pharmacogenetic medications for patients with 1, 3, and 5 years of continuous enrollment is shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. Among 105,547 patients who underwent PCI, who were initiated on antiplatelet therapy, and had at least 1‐year continuous enrollment data, 36.3% were prescribed at least 1 additional drug with CPIC level A evidence, and 50% were prescribed at least 1 additional drug with CPIC level A or B evidence over 1 year. For patients with at least 5 years of follow‐up data, more than one quarter of patients were prescribed three or more CPIC level A or B drugs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of CPIC level A and B drugs prescribed after PCI and antiplatelet initiation among patients with at least 1, 3, and 5 years' follow‐up data in MarketScan (2008–2015)

| Antiplatelet therapy initiators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of prescriptions other than antiplatelet therapy in the 1, 2, and 5‐year follow‐up periods | CPIC Level A or B Drug n (%) | CPIC Level A Drug n (%) |

| 1‐year follow‐up | N = 105,547 | |

| 0 prescriptions | 52,748 (50.0) | 67,254 (63.7) |

| 1–2 | 37,760 (35.8) | 32,804 (31.1) |

| 3–4 | 11,757 (11.1) | 4,782 (4.5) |

| 5–6 | 2,690 (2.5) | 604 (0.6) |

| > 6 | 592 (0.6) | 103 (0.1) |

| 3‐year follow‐up | N = 39,962 | |

| 0 prescriptions | 15,631 (39.1) | 20,969 (52.5) |

| 1–2 | 15,706 (39.3) | 15,264 (38.2) |

| 3–4 | 6,361 (16.0) | 3,328 (8.3) |

| 5–6 | 1,816 (4.5) | 370 (0.9) |

| > 6 | 448 (1.1) | 31 (0.1) |

| 5‐year follow‐up | N = 12,462 | |

| 0 prescriptions | 3,989 (32.0) | 5,577 (44.8) |

| 1–2 | 5,050 (40.5) | 5,299 (42.5) |

| 3–4 | 2,397 (19.2) | 1,389 (11.1) |

| 5–6 | 786 (6.3) | 180 (1.4) |

| > 6 | 240 (2.0) | 17 (0.1) |

CPIC, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Zero, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, and > 6 prescriptions refer to the number of prescriptions for drugs with pharmacogenetic evidence (CPIC level A or B or CPIC level A only) that were prescribed in addition to antiplatelet therapy for cohorts with at least 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years of continuous enrollment.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients prescribed at least one additional Clinical Pharmacogenetic Implementation Consortium (CPIC) drug over 1 year through 5 years following percutaneous coronary intervention.

As shown in Table 4 and Tables S3 and S4 , opioids, PPIs,and simvastatin were the most commonly prescribed pharmacogenetic medications among patients within MarketScan at both 1 and 5 years.

Table 4.

Prevalence of prescribed pharmacogenetics drugs, projected and actual 1‐year genotype‐guided opportunities among post‐PCI patients in MarketScan (n = 105,547) and UF (n = 211)

| Gene | CPIC (Level A or B) | Actionable phenotype | Phenotype prevalence (%) at UF | MarketScan | UF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug prevalence (%) | Projected genotype‐guided opportunities (%) | Drug prevalence (%) | Actual genotype‐guided opportunities (%) | ||||

| CYP2D6 | Oxycodone | PM, IM | 5.2 | 21.4 | 1.1 | 29.9 | 0.9 |

| Codeine | 18.5 | 1.0 | 1.4 | ||||

| Tramadol | 16.3 | 0.8 | 13.7 | ||||

| Methadone | 0.3 | 0.02 | 0.0 | ||||

| Nortriptyline | PM, IM | 5.2 | 0.9 | 0.05 | 1.4 | 0.5 | |

| Desipramine | 0.1 | 0.005 | 0.0 | ||||

| Venlafaxine | 2.6 | 0.1 | 1.4 | ||||

| Risperidone | 0.3 | 0.02 | 0.3 | ||||

| Paroxetine | PM | 1.9 | 2.5 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 0.0 | |

| Fluvoxamine | 0.1 | 0.002 | 0.0 | ||||

| Mirtazapine | 0.9 | 0.02 | 0.5 | ||||

| CYP2C19 | Omeprazole | PM, IM RM, UM | 55.5 | 19.6 | 10.9 | 8.5 | 22.7 |

| Pantoprazole | 16.0 | 8.9 | 36.0 | ||||

| Lansoprazole | 5.1 | 2.8 | 0.5 | ||||

| Rabeprazole | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.0 | ||||

| CYP2C19 | Citalopram | PM, RM, UM | 35.6 | 6.2 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| Escitalopram | 5.1 | 1.8 | 2.4 | ||||

| Voriconazole | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.0 | ||||

| Sertraline | PM | 2.4 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 3.8 | 0.0 | |

| SLCO1B1 | Simvastatin | Low and intermediate transporter activity | 14.7 | 36.6 | 5.4 | 8.1 | 1.9 |

| CYP2C19/CYP2D6 | Amitriptyline | CYP2C19 PM RM/UM/ or CYP2D6 IM/PM | 39.8 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.9 |

| Doxepin | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.4 | ||||

| Imipramine | 0.2 | 0.08 | 0.0 | ||||

| Clomipramine | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| VKORC1 + CYP2C9 | Warfarin | Warfarin sensitive or highly sensitive | 21.8 | 6.0 | 1.3 | 8.1 | 2.4 |

| CYP2C9 | Phenytoin | IM, PM | 24.6 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Celecoxib | PM | 1.4 | 2.7 | 0.04 | 0.5 | ||

| Total genotype‐guided opportunities | 38.5% | 32.2% | |||||

Total projected 1‐year genotype‐guided therapy decisions = (∑ prevalence of actionable phenotype in UF × prevalence of relevant drug over a year in MarketScan).

Actual genotype‐guided opportunity for each gene‐drug/drug‐class was defined as the percentage of patients with the actual phenotype and a prescription for the relevant pharmacogenetic drug. Drugs affected by the CYP2D6 UM phenotype (such as ondansetron) are not listed in the table because copy number variation was not assessed, and, therefore, projected and actual genotype‐guided prescribing decisions were not determined.

CYP2C9, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9; CYP2C19, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 19; CYP2D6, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily D member 6; IM, intermediate metabolizer; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PM, poor metabolizer; RM, rapid metabolizer; SLCO1B1, solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1; UF, University of Florida; UM, ultra‐rapid metabolizer; VKORC1, vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1.

Projecting genotype‐guided drug prescribing opportunities post‐PCI

Among MarketScan antiplatelet initiators with at least 1 year of post‐PCI enrollment data (n = 105,547), the projected, 1‐year incidence of unique genotype‐guided drug prescribing (∑ prevalence of actionable phenotype in UF × prevalence of relevant drug in MarketScan) was 39% (Table 4). This was primarily the contribution of actionable CYP2C19 and SLCO1B1 phenotypes influencing PPIs and simvastatin prescribing decisions. The projected incidence of genotype‐guided prescribing decisions increased to 52% when the 5‐year prevalence data of pharmacogenetic drugs were used (Table S4 ).

Potential genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities within UF

At 1 year post‐PCI and clinical CYP2C19 genotyping at UF Health, 64.9% (137/211) of patients were prescribed a CPIC level A drug and 71.6% (151/211) were prescribed a CPIC A or B drug, in addition to their oral antiplatelet therapy. Results remained unchanged when we excluded patients aged ≥ 65 years to emulate the MarketScan population. The incidence of potential genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities (percentage of patients with actionable phenotypes who were prescribed the relevant pharmacogenetic drug) was 32% (Table 4).

Discussion

This study evaluated the use of pharmacogenetic drugs and the prevalence of corresponding actionable phenotypes among patients with incident PCI who were prescribed antiplatelet therapy. In this analysis, a national sample of privately insured patients within MarketScan was used to identify opportunities for pharmacogenetic testing. Different follow‐up times (1 through 5 years) after PCI were evaluated to mimic minimal and maximum retention times of patients in insurance plans and facilitate decision making regarding the short‐term and long‐term utility of multipharmacogene panel testing.

The analysis of genetic data at UF focused on five genes, which are commonly included on pharmacogenetic panels. The majority of patients analyzed had one or more actionable phenotypes considering these five genes, most commonly for CYP2C19 and CYP2C9. Although the term “actionable genotype/phenotype” was used to refer to a phenotype that would trigger a change in a prescribing decision, it is important to point out that the knowledge of a “normal” phenotype may be equally valuable. For example, following the acute post‐PCI period, knowing that a patient prescribed ticagrelor or prasugrel has a normal CYP2C19 genotype (e.g., *1/*1) could inform switching to clopidogrel in the event this patient is at high risk for bleeding or cannot afford or tolerate the potent antiplatelet agents.25 Therefore, a pharmacogene panel‐based testing can be clinically and economically valuable even if a “normal” genotype that would not trigger a change in therapy is encountered.

In the Pharmacogenomic Resource for Enhanced Decisions in Care and Treatment (PREDICT) cohort, 91% of patients who underwent preemptive genotyping (n = 9,589) were reported to have ≥ 1 actionable genotype.6 The PREDICT cohort included patients who underwent cardiac catheterization, presented with acute lymphocytic leukemia, or had at least a 40% likelihood of exposure to statin, clopidogrel, or warfarin over 3 years according to a prediction model.6 Patients were genotyped for CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and VKORC1 in addition to CYP3A5 and TPMT, which are relevant for tacrolimus and thiopurines, respectively. The latter two genes were not typed in our study, which may contribute to the lower prevalence of actionable phenotypes in our study compared with the PREDICT data. Another study reported that 99% of patients who were enrolled as part of the Mayo Clinic Right Drug, Right Dose, Right Time–Using Genomic Data to Individualize Treatment (RIGHT) protocol had actionable variants in the same genes evaluated in our study.26, 27 The lower prevalence of actionable genotypes in our study compared with the RIGHT cohort may be partially attributed to a high prevalence of CYP2D6 UM phenotype (8%) within the RIGHT cohort, which we did not assess for.26 This likely led to underestimation of the number of CYP2D6‐related actionable phenotypes in our study. Additionally, SLCO1B1 carrier genotypes were more prevalent (> 30%) among the RIGHT cohort, compared with our cohort (15%), which may be attributed to the lower prevalence of African Americans in the RIGHT cohort (< 20%) compared with our UF population (48%).

Within MarketScan, we found that between 50% (1‐year follow‐up) and 68% (5‐year follow‐up) of post‐PCI patients were exposed to at least one pharmacogenetic drug in addition to oral antiplatelet therapy. Opioids, PPIs, simvastatin, ondansetron, selective serotonin re‐uptake inhibitors, and warfarin were among the frequently utilized CPIC medications in this cohort of patients. As a unique component of this study, we combined drug prevalence for patients within MarketScan and actionable phenotype prevalence data for patients with PCI at UF to project on national estimates of incident genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities, if genotyping using a multipharmacogene panel was performed at the time of PCI. We were particularly interested in estimating the short‐term and long‐term utility of panel testing that may translate into economic benefits for insurance plans. Therefore, we calculated a 1 year and 5 year incidence of genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities post‐PCI. Our results found a 1 year incidence of 39% for unique genotype‐guided prescribing beyond CYP2C19‐guided antiplatelet therapy. This value increased to 52% when the projection was performed using drug prevalence data over 5 years of follow‐up. Our findings on pharmacogenetic drug use are in line with a recently published study of eight million veterans, in which 55% of patients were documented to receive at least one CPIC level A in the period of 2011–2017.28 Using 1000 Genomes Project population estimates for actionable genotypes, the investigators projected that SLCO1B1‐simvastatin, CYP2D6‐tramadol, and warfarin‐CYP2C9/VKORC1 would be the most prevalent genotype‐drug interactions in US veterans.28

At UF, the incident genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities were determined at 32%. Although this was a slightly lower value than the projected estimate in MarketScan (39%), our results consistently suggest that preemptive genotyping could have led to genotype‐guided decisions in over a third of patients within the first year of PCI. There were some differences in utilization of pharmacogenetic drugs between the UF and MarketScan cohorts, such as different preferences for opioids and PPIs. This may be explained by institution‐specific prescribing practices, formulary differences, and the small sample size in the UF cohort. Because the prescription data in UF were collected for more recent years (2012–2018) than in MarketScan (2008–2015), secular trends such as shifts toward more potent statins (atorvastatin) in reaction to the 2013 updated practice guidelines29 were noted. Although the analysis in MarketScan captured only outpatient pharmacy dispensing data, UF prescription data were extracted from both inpatient and outpatient records, which may explain the higher and lower prevalence of some drugs, such as ondansetron and codeine (codeine was removed from the UF formulary in 2012), compared with MarketScan.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to focus specifically on patients with PCI, one of the most common settings for pharmacogenetic testing with high insurance reimbursement rates.8 Evaluating the prevalence of pharmacogenetic drugs and opportunities for genotype‐guided prescribing among patients with PCI is important as it marks a decision point and allows for quantification of cost and benefit of multigene panel testing. Such data may support a hybrid testing model (reactive/preemptive) whereby CYP2C19 testing is ordered at the time of PCI (reactive testing) and done as part of a panel of multiple pharmacogenes (preemptive testing). Assuming the cost of panel‐based testing is similar to that of CYP2C19 testing, this hybrid model would create minimal excess financial burden on the health system, while potentially improving prescribing decisions and treatment outcomes for multiple medications that a patient is prescribed across one's lifetime. Although the ultimate goal of precision medicine is to achieve wide implementation of preemptive genotyping, this may seem impractical at present, especially from the payers' perspectives. A model, which focuses and preemptively genotypes high‐risk cardiovascular populations at the time of PCI for the common CPIC gene‐drug pairs, may be a reasonable and cost‐effective alternative.30, 31

Strengths of this study include the use of two data sets (MarketScan and UF) to determine prescribing of pharmacogenetic drugs and identify the potential value of panel‐based testing. Although both genotype and prescription data were available at UF, the data represent local prescribing practices and are limited by the small sample size. On the other hand, MarketScan provides a national sample of healthcare encounter data for > 25 million privately insured patients annually, thus allowing national extrapolations. In our analysis, we relied on the assumption of similarity between the two patient populations. Our results found a high prevalence of pharmacogenetic drug prescribing in both data sets, albeit with some differences within drug classes. Noteworthy, the actual incidence of potential genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities among UF patients (had genetic information been available) and the projected incidence within MarketScan was similar, thus validating our projections.

We acknowledge some limitations in our study. First, we did not capture medications paid out of pocket, and, therefore, medication prevalence in MarketScan might be underestimated. Second, MarketScan includes de‐identified data sets, which precluded linking UF genotype data to medication exposure data to formally assess generalizability. Third, data on race/ethnicity, which affect the prevalence of actionable genotypes, are not available within MarketScan. Our analysis in MarketScan extended from 2008 to 2015, which may not reflect recent changes in prescribing patterns; for example, the recent uptake of new oral anticoagulants or more potent statins. Fourth, we did not assess copy number variations in CYP2D6 or CYP2D6 deletion (*5), which may have underestimated the prevalence of actionable CYP2D6 phenotypes (IM, PM, and UM), and the projected incidence of genotype‐guided decisions for drugs affected by these phenotypes.

In summary, we found a high prevalence of pharmacogenetic medications among a national cohort of privately insured patients and our local UF Health PCI cohort. Further, we found a high prevalence of actionable phenotypes in the UF Health cohort. Combining two data sources, we estimated a 1‐year incidence of genotype‐guided prescribing opportunities at 39% among MarketScan beneficiaries with PCI, which was similar to an actual estimate of 32% within UF. Collectively, these data support the value of panel‐based testing.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH/NHGRI (U01 HG007269), NIH/NCATS (UL1 TR000064 and UL1 TR001427), and Canon Biomedical.

Conflict of Interest

D.J.A. has received payment as an individual for (a) Consulting fee or honorarium from Amgen, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Haemonetics, Janssen, Merck, PLx Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, and The Medicines Company; (b) Participation in review activities from CeloNova and St. Jude Medical. Institutional payments for grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, CeloNova, CSL Behring, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Eisai, Eli‐Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Matsutani Chemical Industry Co., Merck, Novartis, Osprey Medical, and Renal Guard Solutions. F.F. has received payment as an individual for consulting fee or honorarium from Astra Zeneca and Sanofi. N.E.L., A.L., T.L., G.L., A.R., A.E., J.A.J., L.H.C., and A.G.W. declared no competing interests for this work.

Author Contributions

N.E., A.A., T.L., G.L., D.J.A., F.F., A.R., A.E., J.A.J., L.H.C., and A.G.W. wrote the manuscript. L.H.C., J.A.J., and A.G.W. designed the research. N.E. and A.A. analyzed the data.

Supporting information

Table S1‐S4. Diagnostic and Procedure Codes used in identifying Percutaneous Coronary Intervention.

References

- 1. Hopkins, M.M. et al. Putting pharmacogenetics into practice. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 403–410 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cavallari, L.H. et al. Implementation of inpatient models of pharmacogenetics programs. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 73, 1944–1954 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klein, M.E. , Parvez, M.M. & Shin, J.G. Clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics for personalized precision medicine: barriers and solutions. J. Pharm. Sci. 106, 2368–2379 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schildcrout, J.S. , Denny, J.C. & Roden, D.M. On the potential of preemptive genotyping towards preventing medication‐related adverse events: results from the South Korean National Health Insurance Database. Drug Saf. 40, 1–2 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim, G.J. , Lee, S.Y. , Park, J.H. , Ryu, B.Y. & Kim, J.H. Role of preemptive genotyping in preventing serious adverse drug events in South Korean patients. Drug Saf. 40, 65–80 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Driest, S.L. et al. Clinically actionable genotypes among 10,000 patients with preemptive pharmacogenomic testing. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 95, 423–431 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Volpi, S. et al. Research directions in the clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics ‐ an overview of US programs and projects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 103, 778–786 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cavallari, L.H. et al. The IGNITE Pharmacogenetics Working Group: an opportunity for building evidence with pharmacogenetic implementation in a real‐world setting. Clin. Transl. Sci. 10, 143–146 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dunn, S.P. , Holmes, D.R. & Moliterno, D.J. Drug‐drug interactions in cardiovascular catheterizations and interventions. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 5, 1195–1208 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cavallari, L.H. et al. Multi‐site investigation of strategies for the clinical implementation of CYP2D6 genotyping to guide drug prescribing. Genet. Med. 21, 2255–2263 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Antoniou, T. et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population‐based cohort study. CMAJ Open 3, E166–E171 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cavallari, L.H. et al. Institutional profile: University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. Pharmacogenomics 18, 421–426 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cavallari, L.H. et al. Clinical implementation of rapid CYP2C19 genotyping to guide antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Transl. Med. 16, 92 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weitzel, K.W. et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation: approaches, successes, and challenges. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 166C, 56–67 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Langaee, T. , El Rouby, N. , Stauffer, L. , Galloway, C. & Cavallari, L.H. Development and cross‐validation of high‐resolution melting analysis‐based cardiovascular pharmacogenetics genotyping panel. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 23, 209–214 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Langaee, T. , Hamadeh, I. , Chapman, A.B. , Gums, J.G. & Johnson, J.A. A novel simple method for determining CYP2D6 gene copy number and identifying allele(s) with duplication/multiplication. PLoS One 10, e0113808 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Whirl‐Carrillo, M. et al. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 92, 414–417 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Relling, M.V. & Klein, T.E. CPIC: clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium of the pharmacogenomics research network. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 89, 464–467 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Swen, J.J. et al. Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 83, 781–787 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swen, J.J. et al. Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte–an update of guidelines. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 89, 662–673 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hicks, J.K. et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 98, 127–134 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hicks, J.K. et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline (CPIC) for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of tricyclic antidepressants: 2016 update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 102, 37–44 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vandell, A.G. et al. Genetics and clinical response to warfarin and edoxaban in patients with venous thromboembolism. Heart 103, 1800–1805 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crews, K.R. et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype and codeine therapy: 2014 update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 95, 376–382 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Angiolillo, D.J. et al. International expert consensus on switching platelet P2Y. Circulation 136, 1955–1975 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ji, Y. et al. Preemptive pharmacogenomic testing for precision medicine: a comprehensive analysis of five actionable pharmacogenomic genes using next‐generation DNA sequencing and a customized CYP2D6 genotyping cascade. J. Mol. Diagn. 18, 438–445 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bielinski, S.J. et al. Preemptive genotyping for personalized medicine: design of the right drug, right dose, right time‐using genomic data to individualize treatment protocol. Mayo Clin. Proc. 89, 25–33 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chanfreau‐Coffinier, C. et al. Projected prevalence of actionable pharmacogenetic variants and level A drugs prescribed among US veterans health administration pharmacy users. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e195345 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stone, N.J. et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 2889–2934 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dunnenberger, H.M. et al. Preemptive clinical pharmacogenetics implementation: current programs in five US medical centers. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 55, 89–106 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luzum, J.A. et al. The Pharmacogenomics Research Network Translational Pharmacogenetics Program: outcomes and metrics of pharmacogenetic implementations across diverse healthcare systems. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 102, 502–510 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1‐S4. Diagnostic and Procedure Codes used in identifying Percutaneous Coronary Intervention.