Abstract

Introduction

Recruitment into clinical trials is a common challenge experienced by healthcare researchers. Currently, there is little evidence regarding strategies to improve recruitment into clinical trials. However, preliminary research suggests the personalisation of study invitation letters may increase recruitment rates. As such, there is a need to investigate the effectiveness of personalisation strategies on trial recruitment rates. This study within a trial (SWAT) will investigate the effect of personalised versus non-personalised study invitation letters on recruitment rates into the host trial ENGAGE, a feasibility study of an internet-administered, guided, Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) based self-help intervention for parents of children previously treated for cancer.

Methods

An embedded randomised controlled trial (RCT) will investigate the effectiveness of a personalised study invitation letter including the potential participant’s name and address compared with a standard, non-personalised letter without name or address, on participant recruitment rates into the ENGAGE study. The primary outcome is differences in the proportion of participants recruited, examined using logistic regression. Results will be reported as adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Even moderate effects of the personalisation of study invitation letters on recruitment rates could be of significant value by shortening study length, saving resources, and providing a faster answer to the clinical question posed by the study. This protocol can be used as a template for other researchers who wish to contribute to the evidence base for trial decision-making, by embedding a similar SWAT into their trial.

Trial registration

ISRCTN 57233429; ISRCTN 18404129; SWAT 112, Northern Ireland Hub for Trials Methodology Research SWAT repository (2018 OCT 1 1231).

Keywords: Recruitment, Study within a trial, SWAT, Embedded randomised controlled trial

Abbreviations: CBT, Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy; CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; ISRCTN, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trials Number; RCT, Randomised controlled trial; SWAT, Study within a trial

1. Introduction

Successful recruitment of participants is a common challenge to clinical trial conduct. Indeed, a review of publicly funded randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in the United Kingdom identified that only 56% of trials recruited to target, 53% received a recruitment extension, and overall there was substantial variation in recruitment rates across trials [1]. Furthermore, a review of terminated trials in ClinicalTrials.gov indicated in 56.5% of clinical trials, inadequate accrual rate was the reason for early trial termination [2]. Difficulties in participant recruitment result in considerable research waste [3]. For example, successful recruitment is essential for clinical trials to reach statistical power and maximise internal and external validity [4,5]. Further, early trial termination due to poor recruitment may result in unnecessary inclusion of participants in studies that cannot answer important research questions [6] and recruitment delays may negatively affect the health of patients by preventing the realization of timely research impact [5].

In the context of the present host trial ENGAGE [7], the target population are parents of children previously treated for cancer who are experiencing psychological distress. Psychological distress is commonly experienced by parents after the child’s cancer treatment has ended, with parents commonly reporting symptoms of PTSS, depression, anxiety, fear of reoccurrence, and sleep difficulties [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. However, participant recruitment into clinical trials of psychological interventions appears to be particularly difficult. Research focusing on recruitment into depression trials has proposed stigma and barriers related to attitudes towards interventions and trust as contributing factors [12]. Further, depression symptomology (e.g., lack of energy, poor motivation, and difficulties concentrating) may hinder help seeking and partly explain poor recruitment into depression trials [13]. In addition, previous trials of psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic health conditions, including cancer, have experienced difficulties with small sample sizes, thus indicating possible recruitment challenges [14].

Despite the significant negative impact of poor participant recruitment on clinical trials, there is little evidence to inform the utilisation of successful recruitment strategies [15], including within the field of mental health [16]. Recent review findings only identified two recruitment strategies with high-certainty evidence: (1) telephoning non-responders and (2) choosing an open rather than blind trial design [15]. Further, recruitment strategies are often poorly reported in trials, and thus it is difficult to identify potentially effective recruitment strategies from trial reports [17]. Given aforementioned difficulties, the identification of evidence-based strategies to improve clinical trial recruitment is urgently needed.

One suggested recruitment strategy is the personalisation of study invitation letters, whereby potential participants are referred to by their name, rather than receiving generic invitations [18]. Existing evidence from cognitive psychology recognises the use of a person’s name increases the likelihood of attracting attention [19] and helps people filter out competing stimuli and refocus attention [20]. Importantly, seeing one’s name in printed text heightens attention [21]. The personalisation of study invitations has been found to be successful for recruitment rates in survey research [22,23] and an RCT demonstrated breast cancer survivors were more likely to respond to a personalised study invitation e-mail, compared to a non-personalised e-mail [18]. Further, another RCT demonstrated payment of delinquent fines was increased when receiving a personalised text message compared to a non-personalised text message [24]. In addition, inclusion of the name of deceased cancer patients was associated with significantly improved proxy survey response rates from bereaved family members [25]. However, whilst research concerning the use of personalised study invitations shows promise, few studies utilising an RCT design or in the context of clinical healthcare research have been conducted. To the best of our knowledge, no RCT has examined personalisation of study invitations in the context of mental health research.

As such, the objective of the present study within a trial (SWAT) is to investigate the effect of personalised study invitation letters on recruitment rates compared with non-personalised study invitation letters. SWATs are designed to improve the evidence-base concerning trial processes, such as improving recruitment or retention [26] and are typically designed to be embedded into the context of a larger host trial [27]. The present SWAT utilises an RCT design and will be embedded in the host trial ENGAGE [7]. ENGAGE is a feasibility study of an internet-administered, guided, Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) based self-help intervention, EJDeR, for parents of children previously treated for cancer. ENGAGE aims to recruit 50 participants during a six month period between May 2020 and November 2020.

2. Methods

This protocol is reported in accordance with guidelines for reporting embedded recruitment trials [28] based on the Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement 2010 [29].

2.1. Study design

A parallel group embedded RCT to investigate the effect of personalised study invitation letters compared with non-personalised study invitation letters on recruitment rates.

2.2. Participants

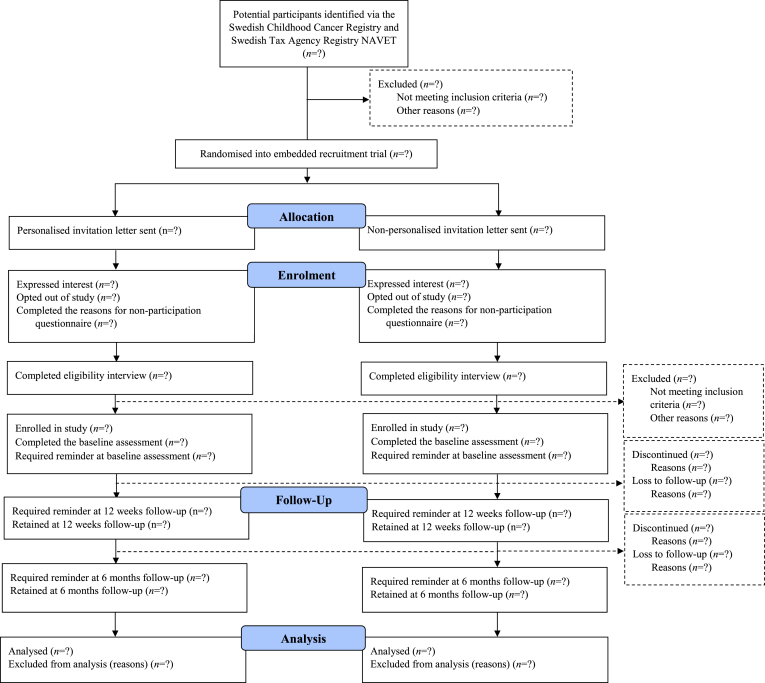

Participants eligible for inclusion in the ENGAGE host trial are: (1) a parent of a child diagnosed with cancer during childhood (0–18 years) who has completed cancer treatment three months to five years previously; (2) lives in Sweden; (3) able to read Swedish; (4) access to e-mail, the internet, and a mobile telephone and/or BankID (Swedish citizen authorisation system); and (5) self-report a need for psychological support. For the purposes of the present recruitment SWAT, all potential participants who are invited to participate in the ENGAGE host trial will be included (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flow of study within a trial (SWAT) participants in the ENGAGE host trial.

2.3. Setting

The ENGAGE intervention, EJDeR (Swedish acronym), is delivered online via the U-CARE-portal (Portal). EJDeR has been visually optimised for use on a computer/laptop screen, however it can also be accessed by participants on mobile devices. Therefore, participants are anticipated to use EJDeR both inside and outside of their own home, or other community settings. Participants will be supported by e-therapists located at the Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala University. Data will be collected online, via the Portal, and/or over the telephone by members of the research team.

2.4. Recruitment

The ENGAGE host trial utilises two recruitment strategies: (1) postal study invitation letters; and (2) social media and patient organisation websites. For the purposes of the SWAT, only participants recruited via postal study invitation letters will be included. However, it is possible that participants recruited via postal study invitation letters may also come across study advertisements on social media and patient organisation websites. To examine this possibility, all participants will be asked about source ofrecruitment (e.g., how did they find out about the study).

Children’s personal identification details will be received from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry (National Quality Registry) and linked to parents’ names and addresses via the Swedish Tax Agency Registry NAVET (Population Registry). Potential participants will be invited in blocks of 100. Data concerning the child's age, gender, cancer diagnosis, and date of first diagnosis will be provided via the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry. Still, upon invitation into the study, the mental health status of the parent will not be known. A study information pack will be sent to each potential participant's home address and will include: a study invitation letter, a study information sheet, a link to the study website and a reply slip with a stamped addressed envelope. As independent study invitation packs will be sent to parents, there is the possibility that two parents of the same child could participate in the study. Study invitation packs clearly state that the study is designed for parents who self-report a need for psychological support related to their child's cancer disease and treatment, moreover this will be asked during the trial recruitment process. Potential participants will also be able to opt out of further contact with the study team by either sending a paper opt out form via the post or completing an opt out form online. Opt out forms include an optional ‘reasons for non-participation’ questionnaire. Full ENGAGE host trial recruitment procedures can be found in the published protocol [7].

2.5. Intervention

Participants will be randomised to receive one of the following interventions:

(1) A personalised invitation letter (Supplementary File 1), including their name and address (intervention group); or (2) non-personalised study invitation letter (Supplementary File 2) not including their name or address (control group). Personalised invitation letters will not include participants’ titles given that titles are rarely used in Sweden. However, invitation letter signatures include the title of the Principal Investigator, as titles are more commonly used for academics in the Swedish context.

The wording of the personalised and non-personalised study invitation letters were designed in consultation with the ENGAGE Parent Research Partner group, consisting of four parents with lived experience of being a parent of a child treated for cancer (see 2.10 Patient and Public Involvement for further details).

2.6. Outcomes

The primary outcome is the effectiveness of the personalised study invitation letter in recruiting participants, in comparison with the non-personalised study invitation letter. As such, the primary outcome is the difference in proportion of participants in the intervention and control group respectively that are enrolled into the ENGAGE host trial. Secondary outcomes are the proportion of participants invited into the study in each group that:

-

•

Express initial interest in participating in the ENGAGE host trial

-

•

Opt out of the ENGAGE host trial

-

•

Complete a reasons for non-participation in the ENGAGE host trial questionnaire

-

•

Complete the eligibility interview for inclusion in the ENGAGE host trial

-

•

Complete the baseline assessment for inclusion in the ENGAGE host trial

-

•

Require a telephone reminder at baseline, post-treatment (12 weeks) and 6-month follow-up for the ENGAGE host trial

-

•

Are retained at post-treatment (12 weeks) and 6-month follow-up for the ENGAGE host trial

Study flow data (see Fig. 1) will be collected online via the Portal or over the telephone with data entered into paper case report forms. All study flow data will be entered into a Microsoft® Access database.

2.7. Sample size

The target sample size of the ENGAGE host trial is 50 participants [7]. As is common for a SWAT, no formal power calculation has been conducted to determine the SWAT sample size, given that the sample size is constrained by the number of participants approached in the ENGAGE host trial [16]. However, following reports recommending a sample size of 50–60 to assess feasibility outcomes and estimate sample size for a definite trial [30,31], we estimate inviting 600 potential participants into the ENGAGE host trial to meet the target sample size of 50, representing a recruitment rate of 8%. The sample size calculation has been outlined in the ENGAGE study protocol [7]. As such, we anticipate the sample of size of present SWAT to be 600, which would provide 90% power to identify a 7.5% difference between the personalised and non-personalised study invitation letter groups in recruitment rate at a two-sided alpha = 0.05.

2.8. Randomisation

Random allocation will be utilised in 1:1 ratio without stratification. Potential participants will be invited into the study using blocks of 100. A de-identified list of potential participants will be prepared by a member of the research team. To ensure allocation concealment, a member of the U-CARE web-development team, external to the research team and not involved in participant recruitment, will produce a computer-generated randomised sequence. The randomisation software has been written specifically for randomisation into the SWAT by a member of the U-CARE web-development team. The software is designed to read a de-identified text file-list of potential participants and outputs the participants in two randomised groups into a CSV file. The participant allocation list will be returned to the research team to implement. To ensure adherence to the randomisation sequence, a 10% sample of invitations after every 50 randomisations will be checked by a member of the research team not involved in participant recruitment. Potential participants will be blind to the SWAT hypothesis and unaware they are part of an embedded trial. It is not possible for the researcher administering the interventions (posting study invitation letters) to be blinded to intervention group status. Participants will be provided with a Recruitment ID number within the study invitation pack dependent on which SWAT intervention they are allocated to. Participants will be required to enter this Recruitment ID number when registering for the study on the Portal. In addition, an allocation list alongside participants’ personal identification number will be stored on a secure USB in a locked filing cabinet.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All analyses will be conducted in SPSS, on an intention-to-treat basis by a statistician blind to group allocation. A two-sided p value of <0.05 will be taken to indicate statistical significance. Numbers and percentages within the personalised and non-personalised study invitation letter groups will be reported for categorical outcomes. Differences in recruitment proportions between groups for the primary and secondary outcomes will be compared, using logistic regression. Logistic regression models stratified by parent gender (male/female) and child gender (male/female) will be constructed, with results reported as an adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals. If two parents of the same child participate this would cause some dependency in the data between the two parents. However, as the number of cases is expected to be very small, data will be analysed as independent. Anonymised data from the SWAT will ultimately be combined in a meta-analysis with data from similar host studies participating in the UK Medical Research Council-funded PROMoting THE USE of SWATs (PROMETHEUS) programme (https://www.york.ac.uk/healthsciences/research/trials/research/swats/prometheus/). However, to the best of our knowledge, no other similar SWATs are currently being conducted by other research groups.

2.10. Patient and Public Involvement

In accordance with Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP) – short form [32], the present study involved the ENGAGE Parent Research Partner group, which includes two mothers and two fathers, aged 45–54 years old, with lived experience of being a parent of a child previously treated for cancer. One Parent Research Partner was previously involved in the development of the Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) based self-help intervention being tested in host trial ENGAGE [33]. A further Parent Research Partner is also an academic member of the department, but otherwise not associated with the present study. The further two Parent Research Partners were recruited via word-of-mouth.

Aim: To assess the appropriateness of suggested wording of the personalised study invitation letter.

Methods: Parent Research Partners were e-mailed three versions of the participant invitation letter drafted by the research team, alongside information concerning the rationale of the SWAT: (1) personalised with both the name of the parent and the name of the child; (2) personalised with only the name of the parent; and (3) non-personalised with no names mentioned. Parents were asked to provide opinions on: (1) including the first name of the child in the personalised invitation letter; (2) including the parent’s full name and address on the top of the personalised invitation letters; and (3) the general wording of the invitation letter. Study invitation letter content, format, and design, including the decision to include a parent's name on the letter signature, was made by the research group, with feedback requested from the Parent Research Partners.

Outcomes: Three out of the four Parent Research Partners advised not to include the child’s name as this could be considered an invasion of privacy. All Parent Research Partners advised to include the full name and address on the top of the personalised invitation letter. In addition, all Parent Research Partners reported that the letter was short, informative, and validating, with no specific word changes suggested.

Reflections: Parent Research Partner input was at the consultation level, whereby feedback was provided on materials already developed by the research team. This approach was invaluable concerning making a decision on which personalised invitation letter should be adopted in the present study. For example, members of the research team felt including the child’s name may have increased personalisation and potentially result in improved recruitment rates. However, feedback from Parent Research Partners was almost unanimous that this may be considered an invasion of privacy, and may have had a negative impact on recruitment. Nonetheless, Patient and Public Involvement may have been further improved by engaging the Parent Research Partners more closely in the drafting of the invitation letters, for example, wording, content, format and design.

3. Discussion

Few recruitment strategies are currently supported by high-quality evidence [16]. As such, researchers conducting clinical trials have little evidence to rely on when making decisions regarding recruitment strategies. The present SWAT protocol addresses this gap by investigating the effectiveness of personalising participant study invitation letters and provides a possible study design template for other researchers planning to embed a similar SWAT within their own clinical trials. This is of particular importance given the need to replicate SWATs, since individual SWATs are often limited by sample size [34] and thus evidence synthesis is required to provide a more precise effect estimate [35]. Even moderate effects of the personalisation of study invitation letters on recruitment rates may be of significant value by shortening study length, saving resources, and providing a faster answer to the clinical question posed by the study.

3.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, results may be limited to trials with access to databases of potential participants’ names and addresses. Indeed, a general limitation of SWATs concerns results being potentially related to the specific context of the host trial, subsequently possibly limiting the generalisability of results [26]. However, mailing letters is a common recruitment strategy [36] and as further SWATs are undertaken, evidence concerning the underlying mechanisms of action behind SWAT recruitment interventions may increase with findings generalizable outside the context of the host trial [26].

Second, it is important to recognise that generating evidence concerning trial processes via SWATs, may be subject to limited time and financial resources [26]. Further, SWATs may experience a number of challenges, such as delays in approval processes concerning ethical aspects and anonymous data sharing regulations [37]. As such, whilst SWATs are able to address important unanswered questions concerning important trial processes, careful decisions should be made to determine the need for a SWAT, to avoid trial resource waste [26]. Third, the sample size of the present SWAT is dictated by the host trial and as such no formal sample size calculation was made. Indeed, small sample sizes constitute a common difficulty experienced by SWATs [34] with host trial sample sizes often not being adequate to detect small but important differences in recruitment rates [38]. Finally, it is currently unknown to what extent non-personalised study invitation letters are used in clinical trials. Indeed, given the accessibility of mail-merge software, inclusion of participants’ names may be common place in clinical trial study invitation letters. Nonetheless, few RCTs have examined the effectiveness of personalising study invitations and given that mail-merging letters can be both resource and time intensive [39], it is important to examine whether personalisation does indeed improve recruitment rates.

However, despite the aforementioned limitations, research to maximise recruitment into mental health trials is of significant importance, given significant difficulties with recruitment are common [12].

Ethics approval

The ENGAGE study has been approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Dnr: 2017/527) and will be conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, ensuring the welfare and rights of all participants, and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. Ethical amendment for the SWAT has been obtained from Swedish Ethical Review Authority August 07, 2019, ref: 2019–03083.

Funding statement

This work is supported by the Swedish Research Council (grant number K2015-99X-20836-08-4 and 2018–02578), the Swedish Cancer Society (grant number 150673 and 180,589) and the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation (grant number PR2017-0005). The funding bodies have not been involved in the development of the study protocol or in writing the manuscript. Author AP’s time was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) [grant number MR/R013748/1] and the views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the MRC or the Department of Health Sciences, University of York .

Declaration of competing interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ylva Hägg Sylvén and Fabian Holmberg for their assistance with randomisation procedure and the York Trials Unit (Department of Health Sciences, University of York) for their support with the study protocol and invitation letters. In addition, the authors wish to thank Simon Ekeström for his administrative support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2020.100572.

Contributor Information

Joanne Woodford, Email: joanne.woodford@kbh.uu.se.

Kajsa Norbäck, Email: kajsa.norback@kbh.uu.se.

Josefin Hagström, Email: josefin.hagstrom@kbh.uu.se.

Helena Grönqvist, Email: helena.gronqvist@kbh.uu.se.

Adwoa Parker, Email: adwoa.parker@york.ac.uk.

Catherine Arundel, Email: catherine.arundel@york.ac.uk.

Louise von Essen, Email: louise-von.essen@kbh.uu.se.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Walters S.J., Dos Anjos Henriques-Cadby I.B., Bortolami O., Flight L., Hind D., Jacques R.M., Knox C., Nadin B., Rothwell J., Surtees M., Julious S.A. Recruitment and retention of participants in randomised controlled trials: a review of trials funded and published by the United Kingdom Health Technology Assessment Programme. BMJ Open. 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams R.J., Tse T., DiPiazza K., Zarin D.A. Terminated trials in the ClinicalTrials.gov results database: evaluation of availability of primary outcome data and reasons for termination. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127242. e0127242–e0127242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillies K., Chalmers I., Glasziou P., Elbourne D., Elliott J., Treweek S. Reducing research waste by promoting informed responses to invitations to participate in clinical trials. Trials. 2019;20:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3704-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borschmann R., Patterson S., Poovendran D., Wilson D., Weaver T. Influences on recruitment to randomised controlled trials in mental health settings in England: a national cross-sectional survey of researchers working for the Mental Health Research Network. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rick J., Graffy J., Knapp P., Small N., Collier D.J., Eldridge S., Kennedy A., Salisbury C., Treweek S., Torgerson D., Wallace P., Madurasinghe V., Hughes-Morley A., Bower P. Systematic techniques for assisting recruitment to trials (START): study protocol for embedded, randomized controlled trials. Trials. 2014;15:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isaksson E., Wester P., Laska A.C., Näsman P., Lundström E. Identifying important barriers to recruitment of patients in randomised clinical studies using a questionnaire for study personnel. Trials. 2019;20:618. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3737-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodford J., Wikman A., Cernvall M., Ljungman G., Romppala A., Grönqvist H., von Essen L. Study protocol for a feasibility study of an internet-administered, guided, CBT-based, self-help intervention (ENGAGE) for parents of children previously treated for cancer. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlsson T., Kukkola L., Ljungman L., Hovén E., von Essen L. Psychological distress in parents of children treated for cancer: an explorative study. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218860. e0218860–e0218860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ljungman L., Cernvall M., Grönqvist H., Ljótsson B., Ljungman G., von Essen L. Long-term positive and negative psychological late effects for parents of childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ljungman L., Hovén E., Ljungman G., Cernvall M., von Essen L. Does time heal all wounds? A longitudinal study of the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of survivors of childhood cancer and bereaved parents. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1792–1798. doi: 10.1002/pon.3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wikman A., Mattsson E., von Essen L., Hovén E. Prevalence and predictors of symptoms of anxiety and depression, and comorbid symptoms of distress in parents of childhood cancer survivors and bereaved parents five years after end of treatment or a child's death. Acta Oncol. (Madr). 2018;57:950–957. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1445286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes-Morley A., Young B., Waheed W., Small N., Bower P. Factors affecting recruitment into depression trials: systematic review, meta-synthesis and conceptual framework. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;172:274–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodford J., Farrand P., Bessant M., Williams C. Recruitment into a guided internet based CBT (iCBT) intervention for depression: lesson learnt from the failure of a prevalence recruitment strategy. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2011;32:641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Law E., Fisher E., Eccleston C., Palermo T.M. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009660.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y., Pencheon E., Hunter R.M., Moncrieff J., Freemantle N. Recruitment and retention strategies in mental health trials – a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treweek S., Pitkethly M., Cook J., Fraser C., Mitchell E., Sullivan F., Jackson C., Taskila T.K., Gardner H. Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised trials. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018 doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearney A., Harman N.L., Rosala-Hallas A., Beecher C., Blazeby J.M., Bower P., Clarke M., Cragg W., Duane S., Gardner H., Healy P., Maguire L., Mills N., Rooshenas L., Rowlands C., Treweek S., Vellinga A., Williamson P.R., Gamble C. Development of an online resource for recruitment research in clinical trials to organise and map current literature. Clin. Trials. 2018;15:533–542. doi: 10.1177/1740774518796156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Short C.E., Rebar A.L., Vandelanotte C. Do personalised e-mail invitations increase the response rates of breast cancer survivors invited to participate in a web-based behaviour change intervention? A quasi-randomised 2-arm controlled trial. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015;15:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0063-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bargh J.A. Attention and automaticity in the processing of self-relevant information. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982;43:425–436. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.43.3.425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherry E.C. Some experiments on the recognition of speech, with one and with two ears. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1953;25:975–979. doi: 10.1121/1.1907229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro K.L., Caldwell J., Sorensen R.E. Personal names and the attentional blink: a visual “cocktail party” effect. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1997;23:504–514. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.23.2.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heerwegh D. Effects of personal salutations in E-mail invitations to participate in a web survey. Public Opin. Q. 2005;69:588–598. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3521523 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muñoz-Leiva F., Sánchez-Fernández J., Montoro-Ríos F., Ibáñez-Zapata J.Á. Improving the response rate and quality in Web-based surveys through the personalization and frequency of reminder mailings. Qual. Quant. 2010;44:1037–1052. doi: 10.1007/s11135-009-9256-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haynes L.C., Green D.P., Gallagher R., John P., Torgerson D.J. Collection of delinquent fines: an adaptive randomized trial to assess the effectiveness of alternative text messages. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2013;32:718–730. doi: 10.1002/pam.21717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu Q., Hassol A., Creel A., Keating N.L. Tailored strategies to enhance survey response among proxies of deceased patients. Health Serv. Res. 2018;53:3825–3835. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Treweek S., Bevan S., Bower P., Briel M., Campbell M., Christie J., Collett C., Cotton S., Devane D., El Feky A., Galvin S., Gardner H., Gillies K., Hood K., Jansen J., Littleford R., Parker A., Ramsay C., Restrup L., Sullivan F., Torgerson D., Tremain L., von Elm E., Westmore M., Williams H., Williamson P.R., Clarke M. Trial Forge Guidance 2: how to decide if a further Study Within A Trial (SWAT) is needed. Trials. 2020;21:33. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3980-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treweek S., Bevan S., Bower P., Campbell M., Christie J., Clarke M., Collett C., Cotton S., Devane D., El Feky A., Flemyng E., Galvin S., Gardner H., Gillies K., Jansen J., Littleford R., Parker A., Ramsay C., Restrup L., Sullivan F., Torgerson D., Tremain L., Westmore M., Williamson P.R. Trial forge guidance 1: what is a Study Within a Trial (SWAT)? Trials. 2018;19:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2535-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madurasinghe V.W., Eldridge S., Bower P., Hughes-Morley A., Collier D., Forbes G., Graffy J., Kennedy A., Knapp P., Rick J., Salisbury C., Small N., Torgerson D., Treweek S., Montgomery A.A., Dack C., Shanahan D.R., Reeves D., Cook J., Campbell M., Brueton V. Guidelines for reporting embedded recruitment trials. Trials. 2016;17:1–25. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1126-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teare M.D., Dimairo M., Shephard N., Hayman A., Whitehead A., Walters S.J. Sample size requirements to estimate key design parameters from external pilot randomised controlled trials: a simulation study. Trials. 2014;15:264. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sim J., Lewis M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012;65:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staniszewska S., Brett J., Simera I., Seers K., Mockford C., Goodlad S., Altman D.G., Moher D., Barber R., Denegri S., Entwistle A., Littlejohns P., Morris C., Suleman R., Thomas V., Tysall C. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2017;358 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3453. j3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wikman A., Kukkola L., Börjesson H., Cernvall M., Woodford J., Grönqvist H., von Essen L. Development of an internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy program (ENGAGE) for parents of children previously treated for cancer: participatory action research approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20:e133. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cochrane A., Welch C., Fairhurst C., Cockayne S., Torgerson D.J. An evaluation of a personalised text message reminder compared to a standard text message on postal questionnaire response rates: an embedded randomised controlled trial [version 1; peer review: 1 approved] F1000Research. 2020;9 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22361.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarathy P.P., Kottam L., Parker A., Brealey S., Coleman E., Keding A., Mitchell A., Northgraves M., Torgerson D., Rangan A. Timing of electronic reminders did not improve trial participant questionnaire response: a randomized trial and meta-analyses. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jolly K., Sidhu M., Bower P., Madurasinghe V., Eldridge S., Graffy J., Parker A., Knapp P., Torgerson D., Treweek S., on behalf of the P.S.M.C. Group, M.R.C.S. Group Improving recruitment to a study of telehealth management for COPD: a cluster randomised controlled ‘study within a trial’ (SWAT) of a multimedia information resource. Trials. 2019;20:453. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3496-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin-Kerry J., Parker A., Bower P., Watt I., Treweek S., Torgerson D., Arundel C., Knapp P. SWATted away: the challenging experience of setting up a programme of SWATs in paediatric trials. Trials. 2019;20:141. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3236-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adamson J., Hewitt C.E., Torgerson D.J. Producing better evidence on how to improve randomised controlled trials. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2015;351 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4923. h4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed R.L., Barton C.A., Isherwood L.M., Baxter J.M.O., Roeger L. Recruitment for a clinical trial of chronic disease self-management for older adults with multimorbidity: a successful approach within general practice. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013;14:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.