Abstract

Background

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is considered as a prognostic predictor of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, its prognostic ability is still controversial. This study aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of NLR changes in HCC patients undergoing transarterial chemoembolization (TACE).

Methods

The patients who were newly diagnosed with HCC and treated with TACE in our center from July 2010 to December 2014 were enrolled in the study. The factors, including NLR, were recorded at baseline and three days and one month after TACE.

Results

A total of 380 consecutive patients were studied retrospectively. The median NLR values at baseline, 3 days and 1 month after TACE (2.4, 6.3 and 2.4 respectively), were used as the cut-off value for patient stratification. Compared with the patients in low NLR group, those with high NLR had a larger tumor size. For baseline measurement, the low NLR group showed improved overall survival (OS) compared with the high group (median OS, 27.1 vs. 15.6 months, P=0.004). There was no survival difference between the low and high NLR groups when measured at 3 days and at 1 month after TACE (P>0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that baseline NLR >2.4 was an independent prognostic predictor of poor OS. There was significant survival difference between the normal NLR group and the high or increased NLR group, with a median OS of 29.1 and 19.1 months, respectively (P=0.023).

Conclusions

The dynamic changes of baseline NLR are significantly associated with OS in HCC patients treated with TACE, and as a result patient selection and prognostic prediction may be refined.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), overall survival (OS), prognosis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading reason for cancer-related death, with 748,000 cases and 695,000 deaths each year (1,2). Two randomized controlled trials demonstrated that transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) could better improve survival in stringently selected patients with unresectable HCC when compared with conservative treatments (3,4).

Interestingly, an elevated ratio of peripheral neutrophils-to-lymphocytes (NLR) has been recognized as a prognostic indicator in various cancers (5). However, the consistency and magnitude of the prognostic impact of baseline NLR in HCC patients treated with TACE remain unclear. Most of the previous studies insisted that baseline NLR is an independent indicator of the overall survival (OS) (6-9); on the contrary, Sullivan et al. found no correlation between NLR and decreased OS (10). Although several studies demonstrated that an improved NLR after TACE was associated with a poor outcome (7,11), Huang et al. believed that an increased NLR indicated a better outcome than a decreased NLR for patients after TACE (12). Consequently, our study aimed to illustrate the dynamic changes of NLR during TACE therapy and evaluate its prognostic value in patients with HCC undergoing TACE.

Methods

Study population

From July 2010 to December 2014, a total of 380 patients with HCC who underwent TACE in Xijing Hospital of Digestive Disease of Fourth Military Medical University were retrospectively enrolled in this study. HCC was diagnosed according to the criteria of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) or the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) (13,14). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) Child-Pugh class A or B (≤7); (II) an ECOG PS score ≤1; (III) patients must have no venous invasion or extrahepatic metastasis; and (IV) patients mustn’t have received any treatment for HCC before. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) patients with diffuse hepatic carcinoma (HCC); (II) patients who had suffered acute or chronic infection recently; and (III) patients affected by other malignant diseases. All patients provided informed consent before undergoing TACE. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Xijing Hospital (Xi’an, China). Written informed consent was given by all patients before receiving TACE therapy, according to the institutional guidelines.

TACE treatment and follow-up

TACE was performed by selective transarterial chemotherapy in the tumor feeding vessels with a suspension of lipiodol (2–20 mL), doxorubicin (10–50 mg), followed by an embolization with absorbable gelatin sponge particles; the infusion continued until a stagnant flow was observed in the feeding vessels. The dosage of doxorubicin and lipiodol was determined based on the tumor size, underlying liver function, and physical status. All patients underwent physical examination and laboratory tests, including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) tests, a liver function panel, and hepatitis serologic tests. CT assessments on intrahepatic tumors were performed 4 to 6 weeks after each TACE procedure. For patients with preserved liver function, repeated TACE sessions were implemented upon confirmation of viable tumor or local and/or distant intrahepatic recurrences.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. The t-test was used for comparison of continuous data between groups and the Pearson chi-square tests were used to compare qualitative variables in clinical pathology analyses. When the expected sample values were low, Fisher’s exact tests were used. Spearman’s rank tests were used to detect correlations between variables. OS was defined as the time from the first session of TACE until death or the last follow-up. Survival analysis was carried out using the Kaplan-Meier method and the differences between curves were assessed by log-rank test. The t-test was used for comparison of continuous data between groups. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to assess the prognostic values of the variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 19.0, and a two-sided P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 380 patients with HCC were enrolled in this study. The median age of patients was 54.3±12.3 years. The study population consisted of 311 men (81.8%) and 69 women (18.2%). The number of patients with HBV infection totaled 320 and accounted for a relatively large proportion of the study patients (84.2%). According to the Child-Pugh classification, 351 patients were classified as A (93.1%) and 26 as B (6.9%). Two hundred thirty nine patients (62.9%) had a solitary tumor. The mean diameter of largest tumor was 7.9 cm. The average number of continuous TACE procedures was 2 (range, 1–12).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (380 patients).

| Variables | Number (%)/mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 54.3±12.3 |

| Sex, male/female | 311 (81.8)/69 (18.2) |

| Aetiology, HBV/non-HBV | 320 (84.2)/60 (15.8) |

| BCLC stage, A/B/C | 57 (15.0)/207 (54.5)/116 (30.5) |

| Child-Pugh class, A/B | 351 (93.1)/26 (6.9) |

| Tumour size (cm) | 7.9±3.8 |

| Tumour number, single/multiple | 239 (62.9)/141 (37.1) |

| AFP, ≤400/>400 ng/mL/NA | 218 (57.4)/160 (42.1)/2 (0.5) |

| Baseline laboratory assessments | |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 45.2±30.2 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 56.1±46.2 |

| Albumin, g/L | 38.8±5.2 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 16.9±7.6 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/d | 0.85±0.8 |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona clinic liver cancer.

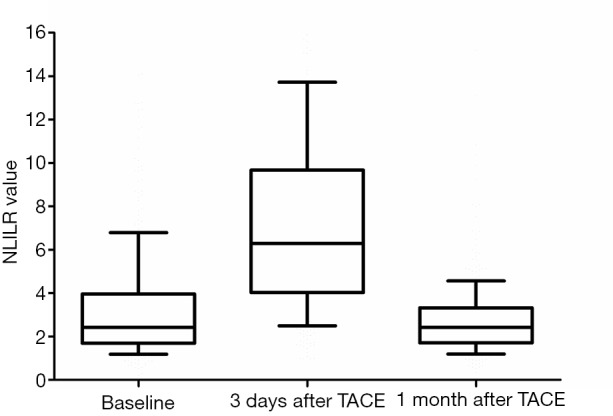

Changes of NLR

The changes of NLR during TACE were as shown in Figure 1. Median NLR of the baseline data was 2.4. When measured at 3 days after TACE, it had increased by up to 6.3. However, median NLR 1 month after TACE went down to 2.4, the same as the baseline. We took 2.4 as a threshold preoperative NLR to distinguish between high (NLR >2.4) and low (NLR ≤2.4) NLR. Similarly, 6.3 and 2.4 were the cut-off NLR values at 3 days and 1 month after TACE, respectively.

Figure 1.

The dynamic changes of NLR in different time-points before or after TACE. NLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Correlation between NLR and clinical characteristics

Of the 380 patients, 187 had NLR value ≤2.4. Clinical and treatment data in the low (≤2.4) NLR and high (>2.4) NLR groups are compared in Table 2. Compared with the patients in low NLR group, those with high NLR had a larger tumor size, higher values of TBIL and AST, and lower values of RBC (P<0.05).

Table 2. Comparison of baseline features between patients with low NLR and high NLR.

| Variables | NLR ≤2.4 (N=187) | NLR >2.4 (N=193) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 154/33 | 157/36 | 0.799 |

| Age | 54.4±12.5 | 54.2±12.1 | 0.667 |

| Etiology (hepatitis B virus/others) | 158/29 | 161/31 | 0.865 |

| Child-Pugh class (A/B) | 177/9 | 174/17 | 0.120 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 7.1±3.4 | 8.6±4.0 | <0.001 |

| Tumor number (single/multiple) | 118/69 | 121/72 | 0.935 |

| AFP (≤400/>400 ng/dL) | 108/78 | 110/82 | 0.879 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 39.3±5.1 | 38.3±5.2 | 0.054 |

| TBIL (µmol/L) | 15.8±6.8 | 18.1±8.1 | 0.004 |

| ALT (U/L) | 44.8±30.9 | 45.6±29.7 | 0.631 |

| AST (U/L) | 45.8±24.1 | 66.0±58.6 | <0.001 |

| Red blood cell (1012/L) | 4.4±0.7 | 4.2±0.7 | 0.020 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 140.2±79.4 | 134.5±86.9 | 0.216 |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; TBIL, total bilirubin.

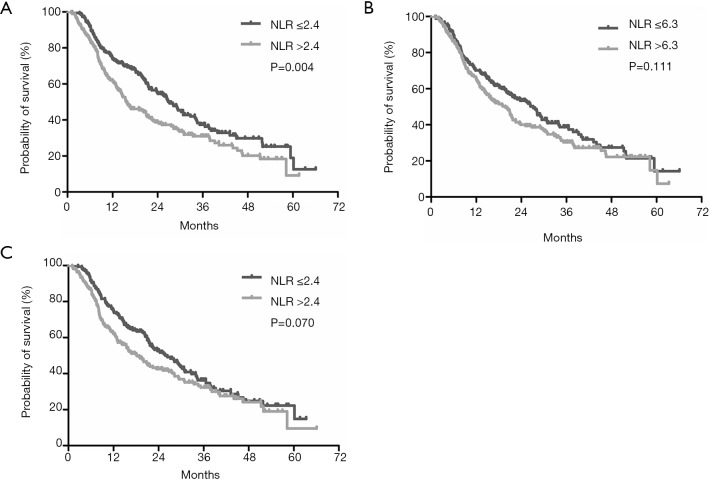

OS

The median follow-up duration was 18.3 months (range, 1.1–66.1 months). At the end of the follow-up period, 247 (65%) patients had died. The median OS was 21.7 months (95% CI: 18.1–25.2 months). At baseline measurement, the low NLR group showed improved OS compared with the high NLR group (median OS, 27.1 vs. 15.6 months, respectively; P=0.004) (Figure 2A). There was no difference between the low NLR group and the high NLR group according to NLR measured three days after TACE with a cut-off value of 6.3 (P=0.111, Figure 2B). However, one month after TACE, the median survival time of low-NLR patients and high-NLR patients was 26.3 and 18.2 months, respectively, meaning the difference was marginally significant (P=0.070, Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves among different groups according to patients’ NLR level. (A) Patients with high NLR vs. patients with low NLR at baseline; (B) patients with high NLR vs. patients with low NLR at three days after TACE; (C) patients with high NLR vs. patients with low NLR at one month after TACE. NLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Prognostic factors

In univariate analyses, six prognostic factors (NLR >2.4, Child-Pugh B, tumor size, tumor number, AFP, and albumin levels) were significantly associated with OS (P<0.05). Multivariable analyses indicated that high NLR (P=0.024) was an independent prognostic factor for OS in HCC patients receiving TACE. Additionally, tumor size, tumor number, AFP level and levels of albumin were also strong predictors for survival in HCC patients undergoing TACE (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analyses for potential risk factors of baseline variables.

| Risk factors | Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Sex (male/female) | 0.98 (0.71–1.35) | 0.914 | – | – | |

| Age (≤55/>55) | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) | 0.244 | – | – | |

| Etiology (HBV/others) | 0.70 (0.49–1.00) | 0.051 | 0.80 (0.49–1.00) | 0.223 | |

| Child-Pugh (B/A) | 1.96 (1.30–2.97) | 0.002 | 1.32 (1.30–2.97) | 0.237 | |

| Tumor size (≤7/>7 cm) | 1.72 (1.33–2.21) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.33–2.21) | <0.001 | |

| Tumor number (single/multiple) | 2.05 (1.60–2.64) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.60–2.64) | <0.001 | |

| AFP (≤400/>400 ng/mL) | 1.87 (1.45–2.40) | <0.001 | 1.77 (1.45–2.40) | <0.001 | |

| Albumin (≤36/>36 g/L) | 0.70 (0.53–0.92) | 0.010 | 0.70 (0.53–0.92) | 0.001 | |

| TBIL (≤17/>17 mg/dL) | 1.26 (0.98–1.62) | 0.077 | 1.26 (0.98–1.62) | 0.688 | |

| NLR (≤2.4/>2.4) | 1.45 (1.13–1.86) | 0.004 | 1.34 (1.03–1.75) | 0.027 | |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; TBIL, total bilirubin.

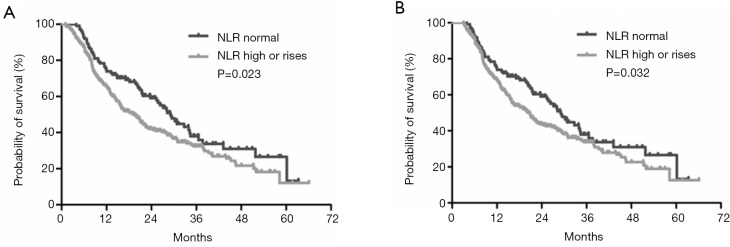

Correlation between changes of NLR and survival

According to the NLR derived at baseline and 1 month after TACE, patients were divided into two groups. Group 1: NLR was normal during TACE (NLR ≤2.4 at baseline and 1 month postoperatively). Group 2: NLR was high or increased (NLR >2.4 at baseline or NLR >2.4 1 month postoperatively). There was significant survival difference between the two groups, with the median survival times of patients with normal NLR and those with high or increased NLR being 29.1 months (95% CI: 25.4–36.6 months) and 19.1 months (95% CI: 15.1–22.9 months), respectively (P=0.023) (Figure 3A). In order to rule out the potential time-dependent bias caused by early death, those patients who died before the evaluation of NLR at 3 months were excluded. Therefore, according to the landmark analysis, the survival difference between these two groups remained significant (P=0.032) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves among different groups of patients according to patients’ NLR level. (A) Patients with normal NRL vs. patients with high or rises at one month for the whole cohort; (B) patients with normal NRL vs. patients with high or rises at one month for the three-month landmark cohort. NLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Discussion

The present study has demonstrated that NLR values increase significantly 3 days after TACE and then fall back to baseline level 1 month thereafter. Moreover, a high NLR (NLR >2.4) independently predicted poor survival in patients with HCC treated with TACE. Similar to our current findings, NLR values have also been shown to predict survival in various cancers including urologic cancer (15), nasopharyngeal cancer (16), colon cancer (17), as well as lung cancer (18). In addition, the NLR has been found to be a prognostic risk factor for HCC after treatments other than TACE, such as hepatectomy (19), liver transplantation (20) and sorafenib therapy (21).

The mechanisms underlying the association between high NLR and poor outcome of cancer patients remain unclear. One potential mechanism may be an association between high NLR and inflammation (22). Neutrophilia as an inflammatory response inhibits the immune system by suppressing the cytolytic activity of immune cells such as lymphocytes, activated T cells, and natural killer cells (23,24). The importance of lymphocytes has been highlighted in previous studies in which increased infiltration of tumors with lymphocytes has been associated with better response to cytotoxic treatment and prognosis in cancer patients (25,26). Another possible explanation could be that inflammatory cytokines and chemokines can be produced by both the tumor and associated host cells such as leukocytes and contribute to malignant progression (26).

Our study also showed that a high or increased NLR 1 month after TACE was associated with poor outcomes in patients with HCC. In this study, a high NLR at the baseline or 1 month after TACE correlates with a poor prognosis, illustrated by a statistical difference in survival curve between the groups of NLR that were always normal and NLR >2.4 at baseline or 1 month post-TACE. Additionally, this study indicated that patients in the high NLR group were characterized by having a larger tumor size, higher values of TBIL and AST, and lower values of RBC. This might be because the tumor size may stimulate the inflammatory response, resulting in a high level of NLR.

Currently, the response to TACE by radiological assessment is a cornerstone in determining treatment efficacy, and plays a critical role in future treatment decision-making processes. Biomarkers such as AFP, play a supporting role. Our study indicated that inflammatory response may take subsidiary function in treatment decision-making. A combination of these biomarkers may be superior and could be clinically useful in predicting the survival of patients with HCC treated with TACE more comprehensively. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

The present study has some limitations. First, it was single-center and retrospective design. It is crucial to evaluate the external validity and reproducibility of the present findings prospectively because the preoperative NLR may provide a simple and inexpensive means of identifying patients with a poorer prognosis. Second, we adopted median baseline NLR 2.4 as a cut-off value, which might not have been optimal despite its great discriminative capacity in distinguish survival. Third, the NLR may have been influenced by several factors.

In conclusion, baseline NLR and its dynamic changes are significantly associated with OS in patients with HCC who are treated with TACE. Given its low cost, availability, and prognostic power, NLR may be incorporated into HCC staging systems to formulate an improved assessment of tumor biology and help clinicians with treatment decision-making.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China 81702999 and the Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi province (2018KJXX-076).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Xijing Hospital (Xi’an, China). Written informed consent was given by all patients before receiving TACE therapy, according to the institutional guidelines.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm.2020.02.113). CW serves as the unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Translational Medicine from Apr 2020 to Mar 2022. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893-917. 10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2012;379:1245-55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359:1734-9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2002;35:1164-71. 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guthrie GJ, Charles KA, Roxburgh CS, et al. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2013;88:218-30. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He CB, Lin XJ. Inflammation scores predict the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who were treated with transarterial chemoembolization and recombinant human type-5 adenovirus H101. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174769. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNally ME, Martinez A, Khabiri H, et al. Inflammatory markers are associated with outcome in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:923-8. 10.1245/s10434-012-2639-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Gong F, Li L, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predict overall survival in non-viral hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Oncol Lett 2014;7:1704-10. 10.3892/ol.2014.1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou DS, Xu L, Luo YL, et al. Inflammation scores predict survival for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma patients after transarterial chemoembolization. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:5582-90. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan KM, Groeschl RT, Turaga KK, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of outcomes for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a Western perspective. J Surg Oncol 2014;109:95-7. 10.1002/jso.23448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinato DJ, Sharma R. An inflammation-based prognostic index predicts survival advantage after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Res 2012;160:146-52. 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang ZL, Luo J, Chen MS, et al. Blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22:702-9. 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-2. 10.1002/hep.24199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Association For The Study Of The Liver, European Organisation For Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer . EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908-43. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo Y, She DL, Xiong H, et al. Pretreatment Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio as a Prognostic Predictor of Urologic Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1670. 10.1097/MD.0000000000001670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun W, Zhang L, Luo M, et al. Pretreatment hematologic markers as prognostic factors in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio. Head Neck 2016;38:E1332-40. 10.1002/hed.24224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner N, Wang HL, Templeton A, et al. Analysis of local chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate combined with systemic inflammation improves prognostication in stage II colon cancer independent of standard clinicopathologic criteria. Int J Cancer 2016;138:671-8. 10.1002/ijc.29805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu G, Yao Y, Bai C, et al. Combination of platelet to lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is a useful prognostic factor in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Thoracic Cancer 2015;6:275-87. 10.1111/1759-7714.12178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mano Y, Shirabe K, Yamashita Y, et al. , Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of survival after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Ann Surg 2013;258:301-5. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318297ad6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motomura T, Shirabe Y, Mano Y, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio reflects hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation via inflammatory microenvironment. J Hepatol 2013;58:58-64. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng YB, Zhao W, Liu B, et al. The blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma receiving sorafenib. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013;14:5527-31. 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.9.5527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to- lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju124. 10.1093/jnci/dju124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrie HT, Klassen LW, Kay HD. Inhibition of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in vitro by autologous peripheral blood granulocytes. J Immunol 1985;134:230-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.el-Hag A, Clark RA. Immunosuppression by activated human neutrophils. Dependence on the myeloperoxidase system. J Immunol 1987;139:2406-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loi S, Sirtaine N, Piette F, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trial in node-positive breast cancer comparing the addition of docetaxel to doxorubicin with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: BIG 02-98. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:860-7. 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.0902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gooden MJ, de Bock GH, Leffers N, et al. The prognostic influence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2011; 105:93-103. 10.1038/bjc.2011.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as