Abstract

Objective

Purpose of the study was to compare lower-limb kinematics and interlimb asymmetry during stair ascent in individuals post-medial or lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA).

Methods

60 patients (20 medial; 10 lateral) post-UKA and 30 matched healthy controls performed stair ascent. Spatio-temporal, lower-limb kinematics and interlimb asymmetries during stair ascent were compared.

Results

Medial-UKA group displayed 5° less knee extension of the UKA limb than controls (p = 0.005) and 2° less than the contralateral limb during stance phase. No interlimb asymmetries were found for lateral-UKA.

Conclusion

Patients post-UKA demonstrate satisfactory lower-limb kinematics and minimal interlimb asymmetry during stair ascent compared to healthy individuals.

Keywords: Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, Gait, Stair, Kinematics, Osteoarthritis

1. Introduction

With improved surgical procedure and implant design, utilization of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) has increased in recent years.1 The purported aim of a UKA is to provide a restoration of knee function closer to a healthy non-surgical knee, compared to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) as the procedure requires less soft tissue dissection, and both cruciate ligaments can be preserved.2,3 Thus, a shorter recovery period,4 better clinical outcomes, like Knee Society scores,5,6 comparable knee extensor strength, leg power and stair maneuver times,7 and similar or better knee kinematics during gait6,8,9 are expected for UKA as those reported in the literature. Moreover, evidence shows that UKA implants have comparable survivor rates with TKA1,10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and lower revision rates.15

UKA procedures and outcomes are still met with skepticism due to challenges of the minimally invasive surgery and mixed clinical results published.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Biomechanical outcomes for individuals with UKA also display equivocal results.6,9,21, 22, 23 It has been reported that individuals post- UKA exhibit satisfactory knee kinematics compared to TKA and healthy individuals.21, 22, 23 Patients with UKA also demonstrate normal quadriceps mechanics to maintain sufficient lower limb functions8 while there is lack observed in peak knee flexion angles at initial contact and maximum extension during the stance phase during walking.9 With evolution of robotic assisted UKA and a subsequent decrease in intraoperative complications, UKA is now considered an efficient and safe procedure.15,24 In addition, most of the studies focus on patients with medial compartment UKA (MED- UKA) and limited evidence is available for patients with lateral compartment UKA (LAT- UKA)25 to make an informed clinical decision on efficacy of UKA for all eligible candidates.

Investigating the performance of daily, functional activities of patients with UKA can provide insight into outcomes post- UKA, especially those at the knee joint. Since the lower limb is a closed kinetic chain, any kinematic change, particularly the knee kinematics on UKA individuals, might influence entire lower limb biomechanics. Atypical knee adduction or abduction of the UKA compared with the non-UKA limb may indirectly indicate inadequate loading on either the intact or implant compartment of the tibiofemoral joint. Consequently, such inadequate loading might contribute to osteoarthritis (OA) development on the intact compartment or wear on the UKA component.26,27

Stair ascent is a muscularly-demanding daily functional activity,28 thus, an excellent movement for functional evaluation of a lower limb UKA.29 There are only few biomechanical UKA investigations on stair ascent available.7,27,30 Weinsteir et al. found that patients with medial UKA displayed a reduced range of knee flexion compared to healthy population.27 However, implant designs and surgical procedures have changed since the study has been published. More recently, De Vroey et al. reported similar results.31 Jung et al. studied patients with UKA in one limb and TKA in another limb.30 They found that UKA limbs only displayed greater knee rotation in the transverse plane compared to TKA limb during stair ascent and Wiik et al. in a similar study report that patients prefer UKA over TKA limb during gait.32 With scarcity of evidence on other activities of daily living such as stair negotiation post- UKA, it is imperative to study such activities to understand the functional and performance outcomes of UKA.

Interlimb gait symmetry/asymmetry is a commonly used biomechanical indicator for clinicians to evaluate functional performance during locomotion.26,33 It has been suggested that asymmetrical interlimb kinematics have been associated with pathological gait.33 Inadequate loading of the lower limb joints may a resultant of asymmetrical interlimb kinematics during locomotion. Thus, it is also valuable to investigate interlimb symmetry in patients with unilateral UKA.

The primary purpose of this study was to determine if individuals in the MED-UKA and LAT-UKA group display similar lower limb stair ascent gait kinematics compared to healthy group (MED-CON and LAT-CON, respectively). The secondary purpose was to determine if clinically-relevant interlimb asymmetries exist within each UKA group compared to the corresponding CON group. It was predicted that no differences for angular or overall gait kinematics would exist between each UKA group compared to the corresponding CON groups. Also, minimal interlimb asymmetries are hypothesized for UKA compared to CON groups.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Sixty healthy participants were recruited. Thirty (30) post-UKA patients with either MED-UKA (n = 20) or LAT-UKA (n = 10) and at least 6 months post-operative duration, non-diseased contralateral limbs, and no other musculoskeletal or other relevant health comorbidity and 30 healthy controls participated in the study (Table 1). The surgery was performed by the same surgeon for consistency and to reduce the potential for surgical error, and the conditions of the contralateral knee was diagnosed as clinically healthy by the surgeon (author xxx) using standard radiographs. All patients received a cemented single-radius, non-side specific, ACL retaining unicondylar knee replacement (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL, USA). The MED-CON (n = 20) and LAT-UKA (n = 10) groups were comprised of healthy participants, each of whom were pair-matched to a UKA participant by age, gender, height (±5 cm), and physical activity level (sedentary, moderately active or very active as determined using the CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire34). For age matching, if the UKA participant's age was less than 59 yr, between 60 and 69 yr, or between 70 and 75 yr, then the matched CON participant's age was ±7 yr, ±5 yr or ±3 yr of the UKA participant's age, respectively. All participants provided written informed consent as approved by the human subjects institutional review board of all institutions involved. The average mechanical preoperative deformity in the MED-UKA group was 4.2° ± 2.5° varus (range, 0°-7°) with 75% of the group displaying fixed deformities requiring ligament release(s) of the deep medial collateral ligament and/or posterior bundle of the superficial medial collateral ligament. The LAT-UKA group had an average of 6.1° ± 3.0° valgus (range, 0°-10°) with 40% of these participants having fixed deformities requiring a lateral collateral ligament, iliotibial tract and/or popliteus tendon release. Postoperative alignments were 2.1° ± 2.2° and 1.3° ± 2.6° for MED- and LAT-UKA group respectively. Details of the radiograph assessment and surgical procedures are described in our earlier reports of this study.35,36

Table 1.

Participants characteristics (mean ± SD) for all participants. Ranges for postoperative time are shown in parentheses. Asterisk mark indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05).

| Group | Gender | Age (yr) | Height (cm) | Mass (kg)* | UKA/Matched Leg Length (cm) | Dominant Limb same as UKA Limb | Postoperative Time (range; months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MED-UKA | M: 8; F: 12 | 69.5 ± 6.7 | 164.8 ± 8.5 | 78.1 ± 16.7 | 87.9 ± 5.9 | 16 | 23 (8–56) |

| MED-CON | M: 8; F: 12 | 68.5 ± 7.9 | 166.1 ± 9.0 | 71.7 ± 13.4 | 90.2 ± 6.8 | NA | NA |

| LAT-UKA | M: 4; F: 6 | 64.1 ± 7.6 | 168.0 ± 6.6 | 73.2 ± 13.3 | 91.1 ± 3.7 | 7 | 18 (6–37) |

| LAT-CON | M: 4; F: 6 | 63.9 ± 6.7 | 169.7 ± 8.5 | 76.4 ± 15.8 | 90.1 ± 4.6 | NA | NA |

2.2. Stair gait analysis

Data collection was conducted in a biomechanics laboratory. Reflective marker locations affixed on the participant were recorded by a seven-camera motion analysis system (Vicon MX-40®; Vicon, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 120 Hz). One force platform (AMTI™ OR6-6-1®; Advanced Mechanical Technology, Inc, Newton, MA, USA), embedded in the floor in front of the first step, and a second platform (FP4060-NC®; Bertec®, Columbus, OH, USA) embedded in the first step were used to measure the vertical ground reaction forces (VGRF) of each foot (1200 Hz). Force platform signals were filtered (4th order Butterworth low-pass filter, 100 Hz cutoff frequency) and used later to ascertain times of initiation and termination of foot contact.35,36 Stairs with four steps (height: 20 cm; depth: 28 cm) and a handrail for use only if the participant required, were used for the stair ascent task.

For each data collection session, anthropometric characteristics of each participant were obtained. Lower limb dominance was determined by the limb used to kick a ball. A total of 36 reflective markers with 14 mm diameter were placed on the upper and lower body segments. Detailed marker locations are described in previous studies.35,36 The participant completed a warm-up by practicing stair locomotion. For the stair ascent task, each participant took two steps on the ground, and then ascended the 4 steps while barefoot at a self-selected, natural speed. Participants performed five successful trials starting with one limb and another five trials starting with the other leg. Limb order was counterbalanced between subjects in the group. A successful trial occurred if the performer ascended the stairs step over step and the foot landed completely on the given force plate.

Data analysis was performed through self-developed programs written in MATLAB® 7.0 (Mathworks, Inc, Natick, MA, USA). Raw marker coordinate data were smoothed using Woltring's generalized cross-validatory spline smoothing technique.37 The interval of interest was the stride initiated when the foot of the start limb contacted the first step and ended when the same foot contacted the third step. Gait events and phases were determined using published algorithms.35,36 Limb dominance was also matched between UKA and corresponding CON participant. For lower-limb modeling, the lower body segments (pelvis, and each thigh, shank, and foot) were assumed to be rigid segments connected by frictionless joints.38, 39, 40 Joint angles of the lower extremities were calculated using Cardan angles.35,36,41 The lower limb joint angles exhibited during stair ascent were adjusted to the angles displayed during natural standing trial. Spatio-temporal gait variables included stride time, relative time of stance and swing phase (% stride time), stride length, and stride velocity for the limb of interest (gait initiation limb). Angular kinematics variables of the sagittal and frontal planes were generated for the stance phase when the limb of interest was on the first step and the subsequent swing phase. Stance phase displacement variables were hip extension and abduction; knee extension and adduction; and ankle dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, and eversion. Those displacements were calculated from initial foot contact to their corresponding peaks, except for ankle plantarflexion displacement was from peak dorsiflexion to peak plantarflexion. Maximum angular displacements generated for the swing phase were hip flexion and adduction; knee flexion and abduction; and ankle dorsiflexion and inversion. These displacements were calculated from foot off to their corresponding peak angle values.

2.3. Statistical analysis

For each spatio-temporal and kinematics variable, the difference between a given UKA and CON group was tested using a paired t-test. Interlimb asymmetries within each group were also tested by paired t-test (α = 0.05). Effect size (Cohen's d) also was reported. A negative effect size indicated the CON group mean was greater than UKA group mean for a given variable. All tests were conducted using SPSS software (IBM Corp., Version 21.0. Armonk, NY).

3. Results

3.1. Spatio-temporal characteristics

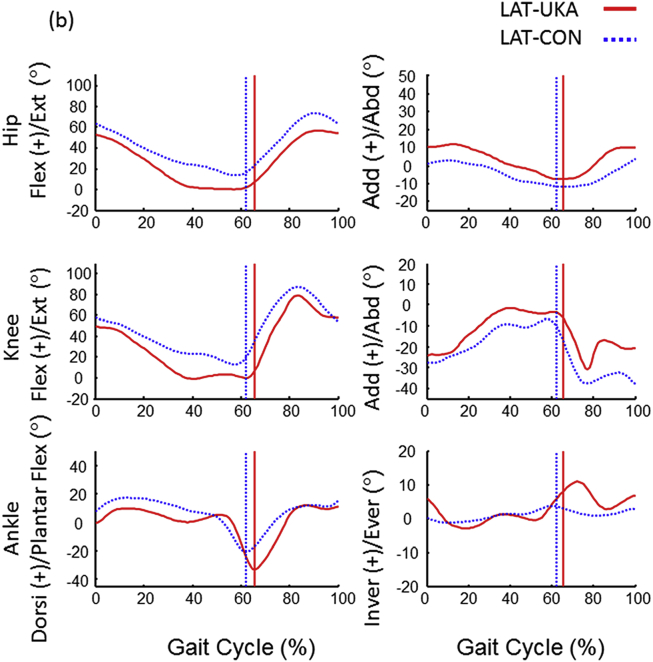

Both UKA groups displayed longer stride time and slower walking velocity than their corresponding CON groups (Table 2). The MED-UKA group had a tendency to display longer relative time of stance phase and shorter of swing phase than MED-CON group (p = 0.006) but the LAT-UKA group did not (p = 0.351). Lower limb kinematics of the sagittal and frontal planes of a representative MED- and LAT- UKA participant and matched CON is shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Spatio-temporal gait variables (mean ± SD) of medial (MED) and lateral (LAT) UKA participants and their matched control groups (CON).

| Stride Time (s) | Relative Time (% Stride Time) |

Stride |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stance Phase | Swing Phase | Length (m) | Velocity (m/s) | ||

| MED-UKA | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 66.1 ± 3.3 | 33.9 ± 3.3 | .6 ± .02 | .4 ± .1 |

| MED-CON | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 64.3 ± 2.3 | 35.7 ± 2.3 | .6 ± .02 | .5 ± .1 |

| p value | 0.015* | 0.060^ | 0.060^ | 0.335 | 0.023* |

| Cohen's d |

0.775 |

0.650 |

−0.650 |

−0.376 |

−0.744 |

| LAT-UKA | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 64.1 ± 2.4 | 35.9 ± 2.5 | .6 ± .01 | .4 ± .04 |

| LAT-CON | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 65.1 ± 1.0 | 34.9 ± 1.0 | .6 ± .02 | .4 ± .04 |

| p value | 0.005* | 0.351 | 0.351 | 0.737 | 0.005* |

| Cohen's d | 1.340 | −0.494 | 0.494 | −0.118 | −1.393 |

Note. Bold and *p value indicates that the UKA group is significantly different from corresponding CON group (p < 0.05). Italic and ^ p value indicates the group difference displays a tendency toward significance (p = 0.051 ~ 0.10).

Fig. 1.

Typical lower limb kinematics on the sagittal and frontal planes of a representative stair ascent trial displayed by medial (MED) unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA, solid red line) patient and their matched control (CON, dotted blue line).

Fig. 2.

Typical lower limb kinematics on the sagittal and frontal planes of a representative stair ascent trial were displayed by lateral (LAT) UKA patient (solid red line) and their matched control (CON, dotted blue line).

3.2. Joint kinematics

For the MED-UKA comparisons, during the stance phase, knee extension displacement of the UKA limb of the MED-UKA group was approximately 5° less than the matched limb of the CON group (p = 0.005, d = −0.947). Otherwise, the MED-UKA and CON matched limb displayed non-significant displacement differences that were less than 3° (p = 0.155 to 0.864; Cohen's d = −0.384 to 0.417). No other significant differences were found in the group comparisons of the non-UKA limb (p = 0.277 to 0.952, and Cohen's d = −0.366 to 0.208). (Table 3a).

Table 3a.

Joint displacement variables (°) displayed during the stance phase of stair ascent by medial (MED) and lateral (LAT) unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) participants and their matched control groups (MED-CON and LAT-CON).

|

Group |

Limb | Hip Joint Displacement (°) |

Knee Joint Displacement (°) |

Ankle Joint Displacement (°) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extension | Abduction | Extension | Adduction | Dorsiflex | Plantarflex | Eversion | ||

| MED-UKA | UKA | 54.2 ± 4.9 | 12.0 ± 6.8 | 52.5 ± 5.4*i | 11.0 ± 5.9i | 7.7 ± 2.8 | 40.5 ± 6.1 | 6.0 ± 2.0 |

| NonUKA | 54.3 ± 5.5 | 12.7 ± 6.6 | 54.7 ± 5.1i | 8.3 ± 6.2i | 8.0 ± 3.1 | 38.7 ± 9.9 | 5.8 ± 1.9 | |

| MED-CON | Matched to UKA | 52.4 ± 4.4 | 12.3 ± 4.3 | 57.7 ± 5.6* | 8.9 ± 4.7 | 6.5 ± 3.2 | 39.3 ± 6.2 | 5.8 ± 2.4 |

| Matched to NonUKA | 53.2 ± 5.8 | 12.8 ± 5.0 | 56.8 ± 6.3 | 8.6 ± 4.2 | 7.6 ± 3.0 | 39.0 ± 5.5 | 5.6 ± 2.4 | |

| LAT-UKA | UKA | 51.5 ± 6.0 | 15.8 ± 7.1^ | 57.3 ± 5.3 | 8.7 ± 7.0 | 7.2 ± 2.6 | 37.7 ± 8.0 | 5.6 ± 1.5 |

| Non-UKA | 50.2 ± 5.6 | 15.5 ± 4.9 | 54.8 ± 5.1 | 11.3 ± 6.3 | 7.1 ± 2.8^ | 40.2 ± 6.2 | 5.1 ± 1.1 | |

|

LAT-CON |

Matched to UKA | 51.1 ± 6.0 | 11.8 ± 3.4^ | 54.1 ± 3.8 | 9.9 ± 7.3^i | 7.6 ± 3.6 | 37.2 ± 5.1 | 5.1 ± 1.8 |

| Matched to NonUKA | 53.2 ± 4.2 | 12.5 ± 5.3 | 53.7 ± 5.7 | 15.0 ± 6.7^i | 6.8 ± 2.6^ | 36.1 ± 4.1 | 5.3 ± 1.9 | |

Bold and * Significant difference (p < 0.05).

Bold andi Interlimb asymmetry (p < 0.05).

Italics and^ Potential significant difference (p = 0.05–0.09).

Italics andi Potential interlimb asymmetry (p = 0.05–0.09).

For the LAT-UKA group compared to LAT-CON group, no differences were found (p = 0.156 to 0.881, d = −0.337 to 0.708). However, compared to the matched CON limb, the LAT-UKA limb had a tendency to display approximately 4° greater hip abduction displacement during stance phase (p = 0.054, d = 0.738) and approximately 2° greater ankle inversion displacement during swing phase (p = 0.096, d = 0.766), but no other differences were observed (p = 0.115 to 0.844, d = −0.780 to 0.675). (Table 3b).

Table 3b.

Joint displacement variables (°) displayed during the swing phase of stair ascent by medial (MED) and lateral (LAT) unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) participants and their matched control groups (MED-CON and LAT-CON).

|

Group |

Limb | Hip Joint Displacement (°) |

Knee Joint Displacement (°) |

Ankle Joint Displacement (°) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | Adduction | Flexion | Abduction | Dorsiflex | Inversion | ||

| MED-UKA | UKA | 59.9 ± 3.8 | 13.2 ± 6.5 | 84.7 ± 6.5 | 17.3 ± 6.0 | 40.4 ± 6.6 | 13.6 ± 4.1 |

| Non-UKA | 57.9 ± 5.5 | 14.3 ± 5.5 | 86.8 ± 6.1 | 15.6 ± 6.5 | 39.2 ± 10.2 | 13.6 ± 6.7 | |

| MED-CON | Matched-UKA | 58.8 ± 5.2 | 14.8 ± 4.0 | 87.5 ± 7.9 | 16.4 ± 5.5 | 39.8 ± 6.7 | 12.8 ± 3.1 |

| Matched-NonUKA | 56.8 ± 5.7 | 14.8 ± 5.1 | 87.5 ± 8.4 | 17.2 ± 5.4 | 39.1 ± 6.0 | 12.5 ± 4.3 | |

| LAT-UKA | UKA | 59.4 ± 5.3 | 18.8 ± 7.5 | 88.6 ± 6.0^ | 16.5 ± 8.3 | 36.8 ± 9.4i | 13.0 ± 2.7i |

| Non-UKA | 57.0 ± 5.1 | 17.6 ± 5.0 | 85.9 ± 6.5^ | 18.4 ± 7.1 | 41.2 ± 7.3i | 13.5 ± 4.3 | |

| LAT-CON | Matched-UKA | 59.9 ± 8.9 | 15.2 ± 4.3 | 88.1 ± 7.8* | 19.6 ± 10.0 | 38.6 ± 6.3 | 11.3 ± 1.9i |

| Matched-NonUKA | 59.7 ± 5.9 | 14.0 ± 5.7 | 85.2 ± 7.4* | 24.2 ± 7.9 | 36.6 ± 6.3 | 12.4 ± 4.0 | |

Bold and * Significant difference (p < 0.05).

Bold andi Interlimb asymmetry (p < 0.05).

Italics and ^ Potential significant difference (p = 0.05–0.09).

Italics and i Potential interlimb asymmetry (p = 0.05–0.09).

For the interlimb symmetry/asymmetry comparisons of the MED groups, the MED-UKA group displayed asymmetry for knee extension displacement during stance phase (p = 0.034, d = −0.427), and had a tendency to display greater adduction displacement of the UKA limb compared to the healthy contralateral limb (p = 0.077, d = 0.447). No other asymmetries were detected for the MED-UKA (p = 0.105 to 0.967, d = −0.332 to 0.424) or MED-CON (p = 0.111 to 0.990, d = −0.346 to 0.358) groups.

No interlimb asymmetries were found for the LAT-UKA group (p = 0.168 to 0.979, d = −0.526 to 0.472). However, the UKA limb compared to the non-UKA limb had a tendency to display greater knee flexion (p = 0.084, d = 0.419) and less ankle dorsiflexion displacements (p = 0.061 d = −0.526) during the swing phase. In the LAT-CON group, the LAT-UKA limb displayed greater knee flexion displacement than the non-implant limb (p = 0.022, d = 0.384) during the stance phase. The matched implant limb also had a tendency to display greater knee adduction during stance phase compared to the matched non-implant limb (p = 0.062 d = −0.788). No other interlimb asymmetries were detected for the LAT-CON group (p = 0.122 to 0.926, d = −0.513 to 0.307).

4. Discussion

Although use of UKA has increased recently biomechanical knowledge of patients with a MED- or LAT-UKA is limited. Therefore, comparing the mechanics of patients with UKA to a matched healthy population for stair ascent, a demanding functional daily task can help establish whether knee outcomes after surgery are restored sufficiently. It was anticipated that, overall locomotor kinematics during stair ascent displayed by both UKA groups would not be different from their matched CON groups. Interlimb asymmetry, if existed, would also be displayed by both UKA groups as well as CON groups. The predictions were mostly supported, as both UKA groups displayed few kinematic differences with their matched CON group. All UKA groups also demonstrated minimal interlimb asymmetry mostly similar to that of the CON groups, with a few exceptions.

For overall gait characteristics, however, it was not anticipated that both UKA groups would ascend the stairs more slowly than their respective CON groups. The 13.7% lower ascent velocity was likely due to the 0.2 s longer UKA stride time. (Table 1). This finding is consistent with findings of other investigators' who reported that their MED- and LAT- UKA groups also ascended more slowly than healthy individuals,42,43 and ascent velocity is within 2% of reported TKA individuals'.44 The finding also indicates that, when using walking speed to evaluate functional performance after surgery, these UKA individuals' speeds of both UKA groups are closer to speeds of TKA individuals and slower than healthy individuals. We are not sure if the knee extensor muscle strength of the UKA or, more likely, the non-UKA limb, was a limiting factor; besides other possibilities were the source of slower walking speed since these were not directly measured in the current study.

There is evidence that UKA individuals may demonstrate mostly typical joint kinematics during stair ascent (Fig. 1 and Table 3a, Table 3b) as predicted. In support of this, first, lower limb kinematic patterns of both UKA and CON groups were consistent with those demonstrated in prior stair ascent literature.43,45, 46, 47 The outcomes of this study are encouraging when compared to stair ascent literature for TKA individuals. In a review of stair ascent/descent TKA research, Standifird, et al. observed that the outcomes in prior literature are mixed, yet deduced that TKA individuals have less knee joint motion during the UKA limb stance phase and reduced stair ascent velocity.48

Another evidence for typical joint kinematics is that there was only one significant angular displacement difference between a UKA group and its CON group. The MED-UKA displayed 5° less knee joint extension displacement than MED-CON group. The MED-UKA individuals contacted the step in an 8° more flexed knee position and extended their knee joint through a 5° greater range (displacement) to raise their body during the stance phase. Two possible explanations for the decreased UKA limb extension are weaker knee extensor strength on the UKA limb and group difference in leg lengths between the MED-UKA and MED-CON groups. Although the results of weaker knee extensor strength as a result of chronic arthritis are inconsistent.7,49 We pair-matched individuals for height, the MED-UKA individuals had, however on average, a 2 cm shorter leg length (no significant difference), which might be clinically relevant.50

The other angular kinematics difference that had tendency to be statistically significant (p = 0.054) was that the UKA limb of the LAT-UKA group displayed 4° more hip abduction displacement than that of the corresponding control group's limb during stance phase. This difference is possibly not due to influences of the kinematics at the knee joint after surgery, as there was less than 2° difference for knee abduction between the LAT-UKA and LAT-CON groups.

The interlimb asymmetry of UKA groups would be similar to non-UKA groups was also mostly supported. There was only one interlimb difference found for the MED-UKA group: the UKA limb displayed 2° less knee extension displacement than the non-operated limb during the stance phase. Also, the LAT-UKA groups had a similar interlimb asymmetry outcome for knee flexion displacement during the swing phase. Compared to the non-UKA limb within each LAT group, the UKA limb of the LAT-UKA group (tendency: p = 0.084) and LAT-CON group, respectively, displayed 3° greater knee flexion displacement. Hence, in comparison with other reported findings,36 interlimb asymmetries might be due more to stair ascent strategies47 than to factors related to the implant. There are several other potential explanations for the small magnitudes of differences and number of variables displaying angular kinematics interlimb asymmetry, such as limb dominance, muscle strength,27,42 and, for UKA groups, implant placement,27 ligament releases, and pre/postoperative knee alignment.27,51 However, limb dominance likely was not an issue, as there was no clear trend for the limb that displayed the greater angular displacement in all groups. If muscle strength of the UKA-limb was considerably less than the non-UKA limb, then there also likely would have been more group and interlimb asymmetry kinematic differences observed and larger magnitudes of interlimb differences within the UKA groups.

Two major limitation of our study are noted. First, our LAT-UKA groups’ sample size was somewhat limited. We recognize that the statistical outcomes of the group comparison could be affected by statistical power. For some angular displacements, especially for LAT group comparisons. However, the nonsignificant group differences, for the most part, were not meaningful, as nearly all mean differences were less than 3°. In light of effect sizes observed, our predictions of few group differences for angular displacements are valid and impacted little by low sample size. We, recommend some caution when interpreting the LAT-UKA findings.

In summary, patients post-UKA have the potential to demonstrate satisfactory lower limb kinematics and normative interlimb asymmetry during stair ascent compared to healthy individuals. Evidence from our study suggests that both medial and lateral UKAs an expect similar biomechanical and functional recoveries and effectively perform activities of daily living. Future studies on the lower limb kinetics are necessary to further investigate joint loading on implant and intact tibio-femoral contact surfaces during functional activities.

Funding source

Arthrex, Inc (Naples, FL, USA).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Rumit Singh Kakar: Data curation, Writing - original draft, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Yang-Chieh Fu: Data curation, Writing - original draft, Investigation. Tracy L. Kinsey: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Cathleen N. Brown: Methodology, Supervision. Ormonde M. Mahoney: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Kathy J. Simpson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

Study was supported by a research grant from Arthrex, Inc.

Acknowledgments

We thank Megan Johnson, CCRP, for her assistance with participant recruitment. We also thank the Athens Orthopedic Clinic staff for their assistance with the study.

References

- 1.Bruce D.J. Minimum 10-year outcomes of a fixed bearing all-polyethylene unicompartmental knee arthroplasty used to treat medial osteoarthritis. Knee. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2020.02.018. PMID: 32220535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callahan C.M. Patient outcomes following unicompartmental or bicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(2):141–150. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassaballa M.A., Porteous A.J., Newman J.H. Observed kneeling ability after total, unicompartmental and patellofemoral knee arthroplasty: perception versus reality. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12(2):136–139. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0376-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lombardi A., Jr. Is recovery faster for mobile-bearing unicompartmental than total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(6):1450–1457. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0731-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs S. Clinical and functional comparison of uni-and bicondylar sledge prostheses. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13(3):197–202. doi: 10.1007/s00167-004-0580-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs S. Quality of life and gait after unicondylar knee prosthesis are inferior to age-matched control subjects. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82(6):441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y. Knee strength, power and stair performance of the elderly 5 years after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28(7):1411–1416. doi: 10.1007/s00590-018-2198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chassin E.P. Functional analysis of cemented medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(5):553–559. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(96)80109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster K.E., Wittwer J.E., Feller J.A. Quantitative gait analysis after medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(6):751–759. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Argenson J.-N.A., Chevrol-Benkeddache Y., Aubaniac J.-M. vol. 84. 2002. Modern unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with cement; pp. 2235–2239. (A Three to Ten-Year Follow-Up Study). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Argenson J.-N.A. Long-term results with a lateral unicondylar replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(11):2686–2693. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0351-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foran J.R.H. Long-term survivorship and failure modes of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):102–108. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2517-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newman J., Pydisetty R.V., Ackroyd C. Unicompartmental or total knee replacement: the 15-year results of a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Bone Jt Surg Br Vol. 2009;91(1):52–57. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.20899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Rourke M.R. The John Insall Award: unicompartmental knee replacement: a minimum twenty-one-year followup, end-result study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;440:27–37. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000185451.96987.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batailler C. Improved implant position and lower revision rate with robotic-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(4):1232–1240. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amin A.K. Unicompartmental or total knee arthroplasty?: results from a matched study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;451:101–106. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224052.01873.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geller J.A., Yoon R.S., Macaulay W. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a controversial history and a rationale for contemporary resurgence. J Knee Surg. 2008;21(1):7–14. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heyse T.J., Tibesku C.O. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery; 2010. Lateral Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: A Review; pp. 1539–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schindler O.S., Scott W.N., Scuderi G.R. The practice of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in the United Kingdom. J Orthop Surg. 2010;18(3):312–319. doi: 10.1177/230949901001800311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verdonk R. The Oxford unicompartmental knee prosthesis: a 2-14 year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13(3):163–166. doi: 10.1007/s00167-004-0522-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akizuki S. In vivo determination of kinematics for subjects having a zimmer unicompartmental high flex knee system. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6):963–971. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banks S.A. Comparing in vivo kinematics of unicondylar and bi-unicondylar knee replacements. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13(7):551–556. doi: 10.1007/s00167-004-0565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandit H. Combined anterior cruciate reconstruction and Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: in vivo kinematics. Knee. 2008;15(2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lonner J.H., Kerr G.J. Low rate of iatrogenic complications during unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with two semiautonomous robotic systems. Knee. 2019;26(3):745–749. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith E. Lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. JBJS reviews. 2020;8(3) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milner C.E. Interlimb asymmetry during walking following unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Gait Posture. 2008;28(1):69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein J.N., Andriacchi T.P., Galante J. Factors influencing walking and stairclimbing following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1986;1(2):109–115. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(86)80048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Startzell J.K. Stair negotiation in older people: a review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5):567–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb05006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andriacchi T.P. A study of lower-limb mechanics during stair-climbing. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol. 1980;62A(5):749–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung M.-C. Difference in knee rotation between total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasties during stair climbing. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(8):1879–1886. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Vroey H. Lower extremity gait kinematics outcomes after knee replacement demonstrate arthroplasty-specific differences between unicondylar and total knee arthroplasty: a pilot study. Gait Posture. 2019;73:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2019.07.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiik A.V. The unicompartmental knee is the preferred side in individuals with both a unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05814-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zifchock R.A. The symmetry angle: a novel, robust method of quantifying asymmetry. Gait Posture. 2008;27(4):622–627. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart A.L. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for olderadults: outcomes for interventions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(7):1126–1141. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu Y.-C. Knee moments after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty during stair ascent. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(1):78–85. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3128-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu Y.-C. Does interlimb knee symmetry exist after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):142–149. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2522-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woltring H.J. A Fortran package for generalized cross-validatory spline smoothing and differentiation. Adv Eng Software. 1986;8:104–113. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu T.-W., O'Connor J.J. A three-dimensional computer graphics-based animated model of the human locomotor system with anatomical joint constraints. J Biomech. 1998;31(Suppl. 1):116. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu T.-W. Validation of a lower limb model with in vivo femoral forces telemetered from two subjects. J Biomech. 1998;31(1):63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu G. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate system of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion--part I: ankle, hip, and spine. International Society of Biomechanics. J Biomech. 2002;35(4):543–548. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grood E.S., Suntay W.J. A joint coordinate system for the clinical description of three-dimensional motions: application to the knee. J Biomech Eng. 1983;105:136–144. doi: 10.1115/1.3138397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costigan P.A., Deluzio K.J., Wyss U.P. Knee and hip kinetics during normal stair climbing. Gait Posture. 2002;16(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(01)00201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riener R., Rabuffetti M., Frigo C. Stair ascent and descent at different inclinations. Gait Posture. 2002;15(1):32–44. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(01)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Catani F. Mobile and fixed bearing total knee prosthesis functional comparison during stair climbing. Clin BioMech. 2003;18(5):410–418. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(03)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin H.-C., Lu T.-W., Hsu H.-C. Comparisons of joint kinetics in the lower extremity between stair ascent and descent. Journal of Mechanics. 2005;21(1):41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Protopapadaki A. Hip, knee, ankle kinematics and kinetics during stair ascent and descent in healthy young individuals. Clin BioMech. 2007;22(2):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reeves N.D. Older adults employ alternative strategies to operate within their maximum capabilities when ascending stairs. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2009;19(2):e57–e68. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Standifird T.W., Cates H.E., Zhang S. Stair ambulation biomechanics following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1857–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossi M.D. An overview of total knee replacement and the role of the strength and conditioning professional. Strength Condit J. 2011;33(3):88–99. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staheli L.T., Williams L. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. Practice of Pediatric Orthopedics. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orishimo K. Does total knee arthroplasty change frontal plane knee biomechanics during gait? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(4):1171–1176. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]