Abstract

Although porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) is a significant pandemic threat in the swine population and has caused significant economic losses, information regarding the immune response in conventionally weaned pigs infected with PDCoV is scarce. Hence, the immune response in conventionally weaned pigs infected with PDCoV was assessed after challenge and rechallenge. After the first challenge, obvious diarrhea and viral shedding developed successively in all pigs in the four inoculation dose groups from 3 to 14 days postinfection (dpi), and all pigs recovered (no clinical symptoms or viral shedding) by 21 dpi. All pigs in the four groups exhibited significantly increased PDCoV-specific IgG, IgA and virus-neutralizing (VN) antibody (Ab) titers and IFN-γ levels in the serum after the first challenge. All pigs were completely protected against rechallenge at 21 dpi. The serum levels of PDCoV-specific IgG, IgA, and VN Abs increased further after rechallenge. Notably, the IFN-γ level declined continuously after 7 dpi. In addition, the levels of PDCoV-specific IgG, IgA and VN Abs in saliva increased significantly after rechallenge and correlated well with the serum Ab titers. Furthermore, the appearance of clinical symptoms of PDCoV infection in conventionally weaned pigs was delayed with reduced inoculation doses. In summary, the data presented here offer important reference information for future PDCoV animal infection and vaccine-induced immunoprotection experiments.

Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV), a member of the genus Deltacoronavirus, family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales, is a newly isolated and identified virus causing watery diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration in pigs of different ages and breeds, especially newborn piglets [1–3]. Since first reported in Hong Kong in 2012 [4, 5], PDCoV has continued to emerge and reemerge in various countries, including the USA [6, 7], Canada [8, 9], South Korea [1, 10], Thailand [11], and mainland China [8, 9], and has caused significant economic losses to the pig industry.

PDCoV is an enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus [7, 12]. The PDCoV genome contains a 5’ untranslated region (UTR) followed by open reading frame 1a/1b (ORF 1a/1b); sequences encoding the spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), accessory protein 6 (NS6), nucleocapsid (N), accessory protein 7 (NS7), and accessory protein 7a (NS7a) proteins; and a 3’ UTR [13, 14]. The E protein is a small envelope protein that plays an important role in viral assembly and infection [15]. The M protein plays an important role in inducing protection and mediating the course of disease [16, 17]. The N protein is principally produced in infected cells and plays multiple roles in viral replication and pathogenesis [13, 18]. The S protein contains three receptor-binding S1 subunits tightly packed into a crown-like structure and three membrane fusion S2 subunits forming a stalk. This protein has several structural features that may facilitate viral immune evasion, including compactness, concealed receptor-binding sites, and shielded critical epitopes [19]. Because the S protein is the major surface protein, it is also the main target of neutralizing antibodies (Abs) during infection and a focus in vaccine design [20].

PDCoV can infect pigs regardless of age; unweaned piglets infected with PDCoV display clinical symptoms similar to those seen in pigs infected with porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), including watery diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration and death [7, 11, 21]. Although previous studies have confirmed the postinfection effect of PDCoV in newborn and suckling piglets, few reports have addressed the pathogenicity of and immune response to PDCoV in conventionally weaned pigs. In addition, although a correlation of resistance to disease induced by PEDV infection with age has been described, little is known about the effect of PDCoV infection and re-challenge on weaned pigs. Therefore, 45-day-old weaned pigs were challenged and rechallenged with different inoculation doses of sixth-passage (P6) culture-adapted PDCoV strain CH/XJYN/2016 (GenBank accession number MN064712), and the immune response in the PDCoV-infected, conventionally weaned pigs was evaluated.

Pig kidney cells (LLC-PK1, ATCC no. CL-101) were grown in minimum essential medium (MEM, Gibco, USA) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen, Australia), 1% antibiotics and antimycotics (10000 units of penicillin, 10000 µg of streptomycin, and 25 µg of Fungizone® [Gibco™, USA], per ml), 1% MEM Non-Essential Amino Acid Solution (MEM NEAA, Gibco, USA), and 1% HEPES (Gibco, Taiwan) and cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2. PDCoV strain CH/XJYN/2016 (GenBank accession number MN064712) was isolated in our laboratory and propagated in LLC-PK1 cells.

Twenty-five 45-day-old PDCoV-naïve conventionally weaned pigs were obtained from a commercial pig farm with no previous herd history of a PDCoV outbreak and confirmed to be seronegative for PDCoV by indirect ELISA (developed in our laboratory). In addition, these pigs were confirmed to be negative for PEDV, TGEV and porcine kobuvirus (PKoV) by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and real-time PCR (developed in our laboratory). The pigs were randomly divided into four experimental groups (G1-G4) and one mock-infected control group, each containing five pigs. Each group of pigs was housed in a different room. Pigs in groups G1 to G4 were separately challenged orally with 3 mL of tenfold serial dilutions (from 100 to 10−3) of P6 cell-culture-adapted CH/XJYN/2016 (original titer: 4.0 log10 TCID50/mL). The mock-infected group received MEM. At 21 days post-inoculation (dpi), pigs in G1 to G4 were rechallenged with 1000 TCID50 of P6 cell-culture-adapted CH/XJYN/2016. After challenge, clinical symptoms were observed and the fecal consistency was scored daily as described previously (scores: 0 = normal, 1 = pasty, 2 = semiliquid, and 3 = liquid) [22]. Serum samples and rectal swabs were collected from all pigs at 0, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 35 dpi. Saliva specimens were collected at 21, 28 and 35 dpi.

An indirect ELISA was developed by our laboratory to measure the serum Ab titers in the pigs. In brief, 96-well plates (Costar, USA) were coated with eukaryotically expressed N protein. Each well was then blocked with 100 μl of a solution containing 1.5% bovine serum albumin (Solarbio, Beijing) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After three washes with PBS (1×, pH 7.2-7.4), the plates were loaded with 100 μl of serum sample (diluted 1:100) or original saliva sample per well. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-pig IgG (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted 1:30,000 (serum) or 1:8,000 (saliva) was added, and the reaction was visualized using 3,3´,5,5´-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (Solarbio®, Beijing). The titers were determined by measuring the optical density (OD) at 450 nm using an ELISA plate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) operated with professional software (SkanIt RE 4.1).

A virus neutralization assay was performed as in our previous study with some modifications [22]. Twofold serial dilutions of serum starting at 1:2 were coincubated at 37 °C for 1 h with equal volumes of viral stock containing 200 TCID50 of PDCoV strain CH/XJYN/2016 in 96-well plates (Corning, USA). Virus-neutralizing (VN) Ab titers were calculated as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution that prevented a cytopathic effect (CPE). The levels of IFN-γ in serum samples from all groups of piglets were determined using a commercial porcine IFN-γ ELISA kit (Solarbio®, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

A real-time PCR method based on the PDCoV N gene was developed in our laboratory. The primer and probe sequences were as follows: sense, 5’-ACGTCGTAAGACCCAGCATC-3’; antisense, 5’-CCCACCTGAAAGTTGCTCTC-3’; probe B, FAM-GTATGGCTGATCCTCGCATCATGGC-BHQ1. The PCR conditions were as follows: 42 °C for 5 min and 95 °C for 10 s, followed by 39 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 57 °C for 20 s. Cycle threshold (Ct) values greater than 30 were considered negative; Ct values less than 30 were considered positive. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16 software. Statistical significance among the different experimental groups was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Differences for which the p-value was less than 0.05 were considered significant.

All piglets were monitored closely before and after the experiment. Prior to the first challenge, all pigs in the five groups were healthy and tested negative for PDCoV-specific IgG Ab and DNA by real-time PCR. After the first challenge with the original concentration and tenfold serial dilutions of P6 cell-culture-adapted CH/XJYN/2016, the clinical symptoms in each group were observed, and fecal viral shedding was detected (Table 1). No obvious clinical symptoms were observed in any pigs in the four experimental groups, and viral shedding in all fecal samples was negative at 1 and 2 dpi. All pigs in the original virus challenge group (G1, n = 5) and the 10−1-diluted virus challenge (G2, n = 5) group exhibited obvious diarrhea and fecal viral shedding at 4 and 6 dpi, respectively (Table 1). In the groups challenged with 10−2-and 10−3-fold dilutions of virus, 3 of 5 and 4 of 5 pigs, respectively, displayed diarrhea and viral shedding at 14 dpi (Table 1). All pigs in groups G1-G4 recovered (no clinical symptoms or viral shedding) by 21 dpi. In addition, no pigs in groups G1-G4 exhibited any obvious clinical symptoms or viral shedding in feces after rechallenge with 3.0 log10 TCID50/ml of virus at 21 dpi (Table 1). The mock-infected control group exhibited no clinical symptoms or viral shedding from 0 to 35 dpi (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the clinical scores and fecal viral shedding for the challenged pigs in each group

| dpia | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Mock | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctd | NPe | CSf | Ct | NP | CS | Ct | NP | CS | Ct | NP | CS | Ct | NP | CS | ||

| 0-2 | -b | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 |

| 3 | a.m.c | 26.35 | 1/5 | 1 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 |

| p.m. | 19.46-20.66 | 2/5 | 2 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 4 | a.m. | 17.5-28.16 | 5/5 | 1-2 | 26.19 | 1/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 |

| p.m. | 16.81-27.86 | 5/5 | 1-3 | 20.86-26.78 | 3/5 | 1 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 5 | a.m. | 17.31-22.38 | 5/5 | 2 | 22.23-29.01 | 4/5 | 1-2 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 |

| p.m. | 14.32-19.25 | 5/5 | 2-3 | 19.58-28.90 | 4/5 | 1-3 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 6 | a.m. | 13.37-18.94 | 5/5 | 2-3 | 19.43-29.82 | 5/5 | 1-3 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 |

| p.m. | 17.01-21.88 | 5/5 | 2-3 | 18.19-27.15 | 5/5 | 2 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 7 | a.m. | 16.88-21.26 | 5/5 | 2-3 | 15.57-17.77 | 5/5 | 2-3 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 |

| p.m. | 17.16-27.87 | 5/5 | 2-3 | 15.88-17.85 | 5/5 | 2-3 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 14 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | 22.88-27.00 | 3/5 | 2-3 | 19.17-29.08 | 4/5 | 1-3 | - | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 21 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 28 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 35 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | - | 0/5 | 0 | |

adays postinoculation (dpi)

bSamples with no Ct value (no PDCoV RNA detected) are indicated by “-”

cThe PDCoV RNA shedding and clinical signs were monitored at 9:00 and 17:00 every day after challenge

dCycle threshold value; a value greater than 30 was considered negative or below the detection limit of real-time PCR

eNumber of PDCoV-positive pigs

fClinical score for fecal consistency: 0 = normal; 1 = pasty; 2 = semiliquid; 3 = liquid

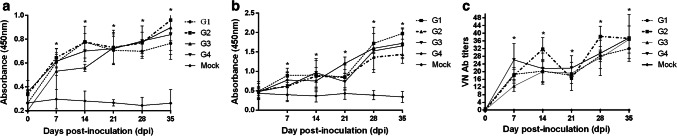

The postinoculation titers of serum PDCoV-specific IgG Abs among G1-G4 pigs showed a sustained increase from 7 to 14 dpi (Fig. 1a). However, the PDCoV-specific IgG Ab titers in G1 and G2 pigs decreased at 21 dpi, whereas those in G3 and G4 pigs continued to increase at 21 dpi (Fig. 1a). This difference may be due to the differences in the onset time of the clinical signs. After rechallenge with a 103 TCID50 dose of P6 cell-culture-adapted CH/XJYN/2016 at 21 dpi, the PDCoV-specific IgG Ab titers in G1-G4 pigs increased further from 28 to 35 dpi (Fig. 1a). The PDCoV-specific IgG Ab titers in the mock-infected control group did not change significantly throughout the experiment (Fig. 1a). The PDCoV-specific IgG Ab titers in G1-G4 pigs were significantly elevated (p < 0.05) compared with those in the mock-infected control group from 7 to 35 dpi (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Serum PDCoV-specific IgG, IgA and VN Ab titers in pigs after two challenges. (a) Serum PDCoV-specific IgG Ab titers in pigs after two challenges. (b) Serum PDCoV-specific IgA Ab titers in pigs after two challenges. (c) Serum VN Ab titers in pigs after two challenges. Blood samples were collected from each pig at 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 days after the first challenge, and the PDCoV-specific IgG and IgA Ab titers were measured using an indirect ELISA developed in our laboratory. The average OD value in each group (n = 5) was measured, and the standard deviation (SD) was plotted at each point. Significant differences among the five groups at 7-35 dpi are indicated by asterisks (p < 0.05). In VN tests, serum samples were heat-inactivated for 30 min at 56 °C before being serially diluted twofold (50 µL) and mixed with a volume equal to 200 TCID50 of the CH/XJYN03/2016 strain. The samples were examined using an inverted microscope on day 5. The VN Ab titer in each serum sample was measured three times, and the average was calculated. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (p < 0.05)

Similar to the serum PDCoV-specific IgG Ab titers, the serum PDCoV-specific IgA Ab titers increased from 7 to 14 dpi in G1-G4 pigs and declined slightly at 21 dpi, except in G4 (Fig. 1b). After rechallenge with a 103 TCID50 dose of P6 cell-culture-adapted CH/XJYN/2016 at 21 dpi, the serum PDCoV-specific IgA Ab titers increased significantly in G1-G4 pigs from 28 to 35 dpi (Fig. 1b). The PDCoV-specific IgA Ab titers in the mock-infected control group did not change significantly throughout the experiment (Fig. 1b). The PDCoV-specific IgA Ab titers in G1-G4 pigs were significantly elevated (p < 0.05) compared with those in the mock-infected control group from 7 to 35 dpi.

In addition, in all G1-G3 pigs, the VN Ab titers increased from 7 to 14 dpi but declined slightly at 21 dpi (Fig. 1c). Similarly, after rechallenge with a 103 TCID50 dose of P6 cell-culture-adapted CH/XJYN/2016 at 21 dpi, the VN Ab titers increased markedly from 28 to 35 dpi (p < 0.05; Fig. 1c). No VN Abs were detected in the mock-infected control group.

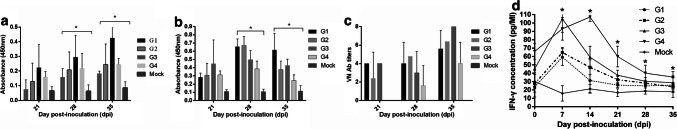

The oral PDCoV-specific IgG titers in G1-G4 increased significantly from 28 to 35 dpi (p < 0.05; Fig. 2a). However, in contrast to the IgG Ab titers, the IgA Ab titers increased from 21 to 28 dpi but declined slightly at 35 dpi (Fig. 2b). In addition, the VN Ab titers in saliva increased from 21 to 35 dpi, except in G3 pigs at 28 dpi (Fig. 2c), whereas the serum IFN-γ levels in G1-G4 pigs increased significantly at 7 dpi (p < 0.05) and then declined continuously from 14 to 35 dpi (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

PDCoV-specific IgG, IgA and VN Abs in saliva after rechallenge. (a) PDCoV-specific IgG Ab titers in saliva after rechallenge. (b) PDCoV-specific IgA Ab titers in saliva after rechallenge. (c) VN Ab titers in saliva after rechallenge. Saliva was extracted by soaking in 1× PBS followed by centrifugation. The average OD value in each group (n = 5) was measured, and the SD was plotted on each bar graph. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (p < 0.05). In the VN tests, saliva samples were heat-inactivated for 30 min at 56 °C, serially diluted twofold (50 µL) and mixed with a volume equal to 200 TCID50 of the CH/XJYN03/2016 strain. The samples were examined using an inverted microscope on day 5. The VN Ab titer in each saliva sample was measured three times, and the average VN Ab titer was calculated. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (p < 0.05). (d) The concentration of serum IFN-γ in weaned pigs after two challenges. Serum IFN-γ levels were measured using a commercial ELISA kit. The concentration of serum IFN-γ was obtained from a standard curve by multiplying by the dilution factor. The average serum IFN-γ levels were calculated, and the SD was plotted at each point. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (p < 0.05)

Almost all previously conducted animal studies with PDCoV have used newborn and suckling piglets as animal models [23] and have indicated that the pathogenicity and clinical symptoms differ in pigs of different ages, a concept called the “age-dependent axis” [24]. Therefore, to better understand the pathogenicity and immune response, this PDCoV infection study used conventionally weaned pigs as an animal infection model.

Unlike piglets, which typically develop diarrhea at 1-2 dpi after PDCoV challenge, the conventionally weaned pigs in groups G1 and G2 in this study developed diarrhea and viral shedding at 3-7 dpi. Furthermore, G3 and G4 pigs exhibited no clinical symptoms or viral shedding up to 7 dpi. These results indicate that the appearance of clinical symptoms induced by PDCoV infection is delayed in conventionally weaned pigs with reduced inoculation doses. A similar pattern has been observed in previous PEDV infection studies [25, 26].

Interestingly, we observed that the levels of IFN-γ were negatively correlated with the challenge dose and that viral rechallenge had no effect on the level of serum IFN-γ. A previous study showed that PDCoV significantly induced expression of IFN mRNA in infected Peyer’s patches at 3 dpi [27]. In this study, however, the levels of serum IFN-γ peaked 7 dpi. The difference may be due to the longer sampling interval. Therefore, a shorter sampling interval will help to obtain more-detailed information about the levels of serum IFN-γ after PDCoV-infection. Generally, swine enteric coronavirus challenge studies use the TCID50 as the infectious titer [11, 21]. Practically, however, the infectious titer of PDCoV strains differs between pigs and cells, but the median pig diarrhea dose (PDD50) of PDCoV in pigs of different ages is unknown. Therefore, before starting this study, a separate experiment was performed, and the results showed that 1000 TCID50 is the lowest dose that can still reliably produce clinical symptoms in weaned pigs. Therefore, in this study, the infection dose used for rechallenge was 1000 TCID50.

In this study, the dynamics of the PDCoV-specific IgG, IgA and VN Ab titers in serum and saliva were determined after PDCoV challenge and rechallenge, and the serum IFN-γ levels were measured. The results indicated that the serum titers of PDCoV-specific IgG, IgA, and VN Abs correlated well with those in saliva and revealed that the appearance of PDCoV-induced clinical symptoms in conventionally weaned pigs is delayed with reduced inoculation doses. Finally, all pigs were completely protected against rechallenge after infection with different PDCoV inoculation doses.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31602095), the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFD0501505), the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-35), and the Central Public Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (Y2016CG23).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All piglets were well cared for during the experiment. Animal care and use protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Donghong Zhao and Xiang Gao have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Donghong Zhao, Email: zhaodonghong123@163.com.

Xiang Gao, Email: 1075474953@qq.com.

Peng Zhou, Email: zhoupeng02@caas.cn.

Liping Zhang, Email: zhanglp2319@163.com.

Yongguang Zhang, Email: zhangyongguang@caas.cn.

Yonglu Wang, Email: wangyonglumd@hotmail.com.

Xinsheng Liu, Email: liuxinsheng@caas.cn.

References

- 1.Jang G, et al. Prevalence, complete genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of porcine deltacoronavirus in South Korea, 2014–2016. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64(5):1364–1370. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Likai J, et al. Porcine deltacoronavirus nucleocapsid protein suppressed IFN-beta production by interfering porcine RIG-I dsRNA-binding and K63-linked polyubiquitination. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1024. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitosh-Sillman S, et al. Experimental infection of conventional nursing pigs and their dams with porcine deltacoronavirus. J Vet Diagn Investig. 2016;28(5):486–497. doi: 10.1177/1040638716654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo PC, et al. Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. J Virol. 2012;86(7):3995–4008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang JQ, et al. Evaluation of two singleplex reverse transcription-Insulated isothermal PCR tests and a duplex real-time RT-PCR test for the detection of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and porcine deltacoronavirus. J Virol Methods. 2016;234:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu H, et al. Isolation and characterization of porcine deltacoronavirus from pigs with diarrhea in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(5):1537–1548. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00031-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homwong N, et al. Characterization and evolution of porcine deltacoronavirus in the United States. Prev Vet Med. 2016;123:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S, Lee C. Complete genome characterization of Korean porcine deltacoronavirus strain KOR/KNU14-04/2014. Genome Announc. 2014;2(6):e01191–14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01191-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L, et al. Porcine deltacoronavirus: histological lesions and genetic characterization. Arch Virol. 2016;161(1):171–175. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2627-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koonpaew S, et al. PEDV and PDCoV pathogenesis: the interplay between host innate immune responses and porcine enteric coronaviruses. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:34. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Z, et al. Porcine deltacoronavirus induces TLR3, IL-12, IFN-alpha, IFN-beta and PKR mRNA expression in infected Peyer’s patches in vivo. Vet Microbiol. 2019;228:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu ZC, et al. A highly pathogenic strain of porcine deltacoronavirus caused watery diarrhea in newborn piglets. Virol Sin. 2018;33(2):131–141. doi: 10.1007/s12250-018-0003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S, Lee C. Functional characterization and proteomic analysis of the nucleocapsid protein of porcine deltacoronavirus. Virus Res. 2015;208:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang PX, et al. Discovery of a novel accessory protein NS7a encoded by porcine deltacoronavirus. J Gen Virol. 2017;98(2):173–178. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo PCY, et al. Coronavirus genomics and bioinformatics analysis. Viruses-Basel. 2010;2(8):1804–1820. doi: 10.3390/v2081803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo SX, et al. Development and application of a recombinant M protein-based indirect ELISA for the detection of porcine deltacoronavirus IgG antibodies. J Virol Methods. 2017;249:76–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vennema H, et al. Primary structure of the membrane and nucleocapsid protein genes of feline infectious peritonitis virus and immunogenicity of recombinant vaccinia viruses in kittens. Virology. 1991;181(1):327–335. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90499-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McBride R, van Zyl M, Fielding BC. The coronavirus nucleocapsid is a multifunctional protein. Viruses-Basel. 2014;6(8):2991–3018. doi: 10.3390/v6082991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shang J, et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of porcine deltacoronavirus spike protein in the prefusion state. J Virol. 2018;92(4):e01556–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01556-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong XL, et al. Glycan shield and fusion activation of a deltacoronavirus spike glycoprotein fine-tuned for enteric infections. J Virol. 2018;92(4):e01628–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01628-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung K, et al. Pathogenicity of 2 porcine deltacoronavirus strains in gnotobiotic pigs. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(4):650–654. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X, et al. Evaluation and comparison of immunogenicity and cross-protective efficacy of two inactivated cell culture-derived GIIa- and GIIb-genotype porcine epidemic diarrhea virus vaccines in suckling piglets. Vet Microbiol. 2019;230:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu H, et al. Experimental infection of gnotobiotic pigs with the cell-culture-adapted porcine deltacoronavirus strain OH-FD22. Arch Virol. 2016;161(12):3421–3434. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langel SN, et al. Lactogenic immunity and vaccines for porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV): historical and current concepts. Virus Res. 2016;226:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng J-Y, et al. Different intestinal tropism of the G2b Taiwan porcine epidemic diarrhea virus-Pintung 52 strain in conventional 7-day-old piglets. Vet J. 2018;237:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xinsheng L, et al. A newly isolated Chinese virulent genotype GIIb porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain: biological characteristics, pathogenicity and immune protective effects as an inactivated vaccine candidate. Virus Res. 2019;259:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhichao X, et al. Porcine deltacoronavirus induces TLR3, IL-12, IFN-α, IFN-β and PKR mRNA expression in infected Peyer’s patches in vivo. Vet Microbiol. 2019;228:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]