This study suggests that cancer survivorship care planning is heterogeneous and may not need to be comprehensive, but rather tailored to individual survivors' needs.

Abstract

Introduction:

Although survivorship care recommendations exist, there is limited evidence about current practices and patient preferences.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was completed by survivors of lymphoma, head and neck, and gastrointestinal cancers at an academic cancer center. The survey was designed to capture patients' reports of receipt of survivorship care planning and their attitudes, preferences, and perceived needs regarding content and timing of cancer survivorship care information. Elements of survivorship care were based on the Institute of Medicine recommendations, literature review, and clinical experience.

Results:

Eighty-five survivors completed the survey (response rate, 81%). More than 75% reported receiving a follow-up plan or appointment schedule, a monitoring plan for scans and blood tests, information about short- and long-term adverse effects, and a detailed treatment summary. These elements were reported as desired by more than 90% of responders. Approximately 40% of these elements were only verbally provided. Although more than 70% described not receiving information about employment, smoking cessation, sexual health, genetic counseling, fertility, or financial resources, these elements were not reported as desired. However, “strategies to cope with the fear of recurrence” was most often omitted, yet desired by most respondents. Survivors' preferences regarding optimal timing for information varied depending on the element.

Conclusions:

Our study suggests that cancer survivorship care planning is heterogeneous and may not need to be comprehensive, but rather tailored to individual survivors' needs. Providers must assess patient needs early and continue to revisit them during the cancer care continuum.

Introduction

Improvements in cancer therapies and treatment strategies have led to significant gains in survival over the past decades. It is estimated that there are 13.7 million cancer survivors in the United States, and the survivor population is expected to increase to 18 million by 2022.1 Despite improved outcomes, post-treatment survivors face an array of health care needs.2–4 Underscoring the significance of post-treatment care, the report “From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition” by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) found that these needs are often not met.4 Several professional oncology associations recommend patients who complete primary treatment be provided with a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan document that is clearly and effectively explained.5–7 Others have proposed that this survivorship care plan (SCP) be designed as an ongoing record of patient care,8 aimed to optimize continuity and coordination of care between patients, their oncology care providers, and primary care clinicians. Further, it has been proposed that SCPs are not meant to serve as the sole survivorship source document, but rather as a vehicle to distribute patient-centered survivorship care information.4,9

The survivorship literature catalogs a diversity of patient needs, including information on diagnosis, diagnostic testing, and treatments received,10–12 short- and long-term treatment toxicity,3,13,14 emotional impact of cancer and/or its treatment,15,16 and screening for second cancers and recurrences.18,19 Other informational needs include age related screenings,20,21 fertility,22 nutrition,20 exercise,12 genetic counseling,4,17 sexual health,23,24 integrative medicine,4,25 pain management,4 smoking cessation,4,26 financial,27,28 employment and legal protections,29,30 and the availability of psychosocial services.31 Whether this information should be included in survivorship care planning for all survivors and what the optimal timing for providing such information are not known. The goals of our study were to understand the reported receipt, desire, and preferred timing of survivorship care planning elements.

Methods

Study Design

A cross-sectional survey was completed by survivors in the lymphoma, head and neck, and GI disease centers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, MA. The survey was designed to capture survivors' attitudes, preferences, and reported information needs for cancer survivorship care. The study was approved by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board.

Patient Eligibility and Recruitment

We identified patients 18 years or older treated with curative intent in the lymphoma, head and neck, and GI oncology programs at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute's main campus. This was a sample of convenience, and our intent was to implement a follow-up survey within our institution's remaining disease centers.

Patients had to have completed treatment ≥ 6 months and ≤ 6 years from enrollment and have no evidence of recurrence. Participant recruitment and surveys were completed in a disease center before beginning the next disease center. First, an informatics report was generated using a specified criterion. Second, electronic medical record review confirmed eligibility. Third, eligible patients were mailed an invitational packet containing a letter, an “opt out” response form, consent form, and a preaddressed stamped envelope. If eligible patients did not respond within 3 weeks, they were contacted by telephone and were provided study details, and the consent form was reviewed. Enrolled participants were approached in clinic before a scheduled visit to compete the online survey on a tablet computer.

For the purposes of this study, within each disease group, we identified and contacted 35 eligible survivors. We recorded rates and reasons for nonparticipation.

Survey Instrument

The online survey was developed on the basis of a review of the literature and the clinical experiences of the study team. The creation of the survey predated the release of the LIVESTRONG Essential elements. The 21 items in our instrument reflected the content themes of the 2005 IOM recommended elements for an SCP. Our reference to “elements” is reflective of specific items of care that have consensus value to cancer survivors. The questions were designed to evaluate the patients' perception of whether information elements were provided to them, whether the information was provided in writing and/or verbally, whether they desired this information, and the optimal time to receive each of the elements. Additional questions included demographics, employment, education, insurance, household income, cancer diagnosis, age at diagnosis, and treatment received. The patient survey was available in English and was tested for content validity and readability with two patients, two oncologists, and an epidemiologist. Minor changes were made to reflect the feedback.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess response rates, reasons for nonparticipation, describe the characteristics of the study population, and report on responders' answers to each of the survey items.

Results

Study Population

Among the 105 eligible survivors, 85 participated, for a response rate of 81%. Seven nonresponders(35%) reported not being interested, and an equal number reported schedule conflicts. Two nonresponders (10%) had originally agreed to participate, but they did not ultimately have their clinic visit as planned, and two (10%) declined after reviewing the consent. One nonparticipant (5%) was too fatigued, and another (5%) did not want to spend any extra time at Dana-Farber to complete the survey.

Approximately half (51%) of responders were male, 89% were white, and 74% were married (Table 1). The age range at diagnosis was 20 to 72 years (mean, 52 years). More than 65% of responders were college graduates, and almost 35% had postgraduate degree. Approximately two thirds (65%) of responders reported at least working part-time, and more than half (51%) reported full-time employment. All responders had insurance coverage, and almost 60% reported income greater than $75,000 per year, with 39% earning more than $100,000 per year. The respondents were approximately equally distributed among the three disease groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population (N = 85)

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 43 | 51.0 |

| Female | 42 | 49.0 |

| Race/ethnicity (n = 81) | ||

| African-American or Black | 2 | 2.3 |

| White | 76 | 89.4 |

| Asian | 1 | 1.2 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | 1.2 |

| Other | 5 | 5.9 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 | 1.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 63 | 74.1 |

| Living as married | 2 | 2.4 |

| Single, never married | 7 | 8.2 |

| Widowed | 3 | 3.5 |

| Divorced | 10 | 11.8 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Less than college | 17 | 20.4 |

| Some college | 11 | 13.3 |

| College graduate | 26 | 31.3 |

| Postgraduate | 29 | 34.9 |

| Employment status (n = 82) | ||

| Full-time | 42 | 51.2 |

| Part-time | 16 | 17.0 |

| Homemaker | 4 | 4.9 |

| Unemployed | 3 | 3.6 |

| Receiving disability | 6 | 7.3 |

| Retired | 17 | 19.5 |

| Other | 2 | 2.4 |

| Insurance status (n = 84) | ||

| Currently has health insurance | 84 | 100 |

| More than one insurance | 16 | 19 |

| Household income, $ (n = 77) | ||

| Less than 10,000 | 1 | 1.3 |

| 10,000 to 29,000 | 5 | 6.5 |

| 30,000 to 49,000 | 11 | 14.3 |

| 50,000 to 74,000 | 14 | 18.2 |

| 75,000 to 99,000 | 16 | 20.8 |

| 100,000 or more | 30 | 39.0 |

| Disease site (n = 85) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 30 | 35.3 |

| Lymphoma | 28 | 32.9 |

| Head and neck | 27 | 31.8 |

| Treatment (n = 85) | ||

| Radiation | 41 | 48.2 |

| Surgery | 51 | 60.0 |

| Chemotherapy | 65 | 76.5 |

| Stem-cell transplantation | 3 | 3.53 |

| Other | 4 | 4.71 |

Elements of Survivorship Care Received and Desired

When responders were asked if they had received survivorship care information either verbally, in writing, or both, the most common elements they reported having received were a follow-up plan or appointment schedule (98.8%), a monitoring plan for scans and blood tests (94.1%), information about long-term effects (92.6%), a detailed treatment summary (83.6%), information regarding short-term adverse effects (77.2%), and screenings for new cancers (75.9%; Table 2). Nearly 40% of these desired elements were provided verbally only.

Table 2.

Information Survivors Reported Receiving and Wanting

| Information | Received Verbally Only (%) | Received Written Only (%) | Received Verbally, Written or Both (%)* | Not Received (%) | Not Received but Wanted (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up plan or appointment schedule | 36.9 | 1.2 | 98.8 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Monitoring plan scans, blood tests | 43.5 | 2.4 | 94.1 | 5.9 | 20.3 |

| Late effects > 2 years after treatment | 24.7 | 33.0 | 92.6 | 7.4 | 0.0 |

| Detailed summary of treatment | 21.2 | 5.9 | 83.6 | 16.4 | 43.0 |

| Screening for new cancer diagnosis | 44.6 | 0.0 | 75.9 | 24.2 | 59.9 |

| Adverse effects first 1-2 years after treatment | 30.2 | 2.4 | 77.2 | 22.9 | 84.3 |

| Nutrition | 18.8 | 14.2 | 68.3 | 31.8 | 55.7 |

| Exercise | 25.0 | 6.0 | 59.6 | 40.5 | 47.2 |

| Support groups for survivors | 14.8 | 7.4 | 49.4 | 50.6 | 36.6 |

| Pain symptom management | 20.7 | 3.7 | 47.6 | 52.5 | 30.3 |

| Coping after treatment is over | 19.5 | 3.7 | 43.9 | 56.1 | 41.4 |

| Family adjustment after cancer | 11.1 | 2.5 | 37.1 | 63.0 | 43.2 |

| Integrative medicine | 14.6 | 7.3 | 36.5 | 63.5 | 44.3 |

| Resources around health Insurance | 10.8 | 4.8 | 33.7 | 66.3 | 25.5 |

| Strategies for fear of recurrence | 13.4 | 0.0 | 29.3 | 70.8 | 67.2 |

| Financial resources | 6.1 | 4.9 | 20.8 | 79.3 | 29.3 |

| Fertility | 10.1 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 81.0 | 12.5 |

| Genetic counseling | 9.7 | 0.0 | 18.0 | 81.9 | 27.1 |

| Sexual health | 11.3 | 1.3 | 16.4 | 83.8 | 31.4 |

| Vocational employment counseling | 3.8 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 93.7 | 22.9 |

| Smoking cessation | 1.3 | 1.3 | 6.5 | 93.5 | 7.0 |

Percentage of participants who received information on elements of survivorship care in any form.

Among the most commonly omitted elements, by report, were information about employment counseling (93.7%), smoking cessation (93.5%), sexual health (83.8%), genetic counseling (81.9%), fertility (81.0%), financial resources (79.3%), and strategies for coping with the fear of recurrence (70.8%). Other elements reported to have been omitted are outlined in Table 2. As depicted in Table 2, survivors expressed variable levels of desire for these elements when they were not received.

Optimal Timing to Provide Information

Responders were asked when during their cancer care it would have been important to receive information on the recommended elements (Table 3). Many preferred to receive specific elements throughout the cancer care continuum, while other elements were preferred at specific time points. “At diagnosis” was the most commonly desired timing for fertility information (22.4%). “From diagnosis through follow-up” was the most desired timing for at least half of the elements, including nutrition (47.1%), exercise (45.9%), monitoring plan (42.4%), short-term adverse effects (38.8%), and pain management (38.8%). “End of treatment” was the most desired timing for information about coping after treatment (40.0%), family adjustment (29.4%), support groups (25.9%), and receipt of a treatment summary (36.5%). “During follow-up” was the most common desired timing for information regarding long-term effects (48.2%), screening for new cancers (42.4%), and strategies for coping with fear of recurrence (34.1%). Responders indicated not needing information at any time about a range of elements (as outlined in Table 3).

Table 3.

Survivors' Preferences for Timing of Information

| Information | At Diagnosis (%) | During Treatment (%) | End of Treatment (%) | During Follow-Up (%) | Diagnosis Through Follow-Up (%) | Not Sure (%) | Do Not Need (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detailed summary of treatment | 29.4 | 25.9 | 36.5 | 15.3 | 35.3 | 3.5 | 7.1 |

| Follow-up plan/appointment schedule | 14.1 | 16.5 | 35.3 | 36.5 | 38.8 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Monitoring plan scans, blood work | 16.5 | 15.3 | 37.7 | 41.2 | 42.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Adverse effects first 1-2 years | 21.2 | 14.1 | 34.1 | 38.8 | 38.8 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| Late effects > 2 years | 17.7 | 8.2 | 25.9 | 48.2 | 43.5 | 2.4 | 3.5 |

| Screening for new cancers | 10.6 | 10.6 | 29.4 | 42.4 | 37.7 | 2.4 | 3.5 |

| Strategies for fear of recurrence | 9.4 | 10.6 | 30.6 | 34.1 | 29.4 | 5.9 | 14.1 |

| Coping after treatment | 7.1 | 12.9 | 40.0 | 27.1 | 22.4 | 9.4 | 21.2 |

| Family adjustment | 10.6 | 14.1 | 29.4 | 24.7 | 25.9 | 10.6 | 25.9 |

| Support groups | 10.6 | 9.4 | 25.9 | 20.0 | 21.2 | 11.8 | 24.7 |

| Pain symptom management | 23.5 | 21.2 | 14.1 | 12.9 | 38.8 | 0.0 | 28.2 |

| Integrative medicine | 22.4 | 9.4 | 14.1 | 10.6 | 30.6 | 8.3 | 22.4 |

| Nutrition | 22.4 | 18.8 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 47.1 | 1.2 | 12.9 |

| Exercise | 18.8 | 16.5 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 45.9 | 3.5 | 14.1 |

| Genetic counseling | 15.3 | 1.2 | 8.2 | 15.3 | 14.1 | 16.5 | 32.9 |

| Fertility | 22.4 | 4.7 | 7.1 | 10.6 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 50.6 |

| Sexual health | 20.0 | 11.8 | 14.1 | 17.7 | 22.4 | 4.7 | 35.3 |

| Smoking cessation | 9.4 | 3.5 | 5.9 | 3.5 | 14.1 | 9.4 | 54.1 |

| Financial resources | 23.5 | 3.5 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 25.9 | 8.3 | 34.1 |

| Vocational employment counseling | 8.2 | 3.5 | 9.4 | 11.8 | 14.1 | 10.6 | 49.4 |

| Resources around health insurance | 25.9 | 3.5 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 25.9 | 8.2 | 31.8 |

NOTE. Boldface indicates most commonly reported timing for the information, or information items “not needed.”

Discussion

In this survey of cancer survivors, we found that more than 75% of participants reported receiving verbally and/or in writing a follow-up plan or appointment schedule, a monitoring plan for scans and blood tests, information about short- and long-term adverse effects, and a detailed treatment summary. Although these items were desired by most more than 90% of the participants, “strategies to cope with the fear of recurrence” was the element reported to have most often omitted yet desired. Optimal timing for information varied by element, beginning at the time of diagnosis through follow-up post treatment.

Our study found that some of the desired elements were provided to patients, but many other elements were omitted These findings are consistent with recent studies that showed that fewer than half of IOM content recommendations were contained within SCPs evaluated from seven National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Centers8 and six community-based centers.32 Although our study did not specifically evaluate the SCP content, we found that survivors reported receiving certain elements. It is both reassuring and surprising that more than 75% reported receiving information on the six elements of care they perceived as most essential. However, in evaluating the method of information conveyance as it relates to the six core elements, we found that approximately 40% of the information was received only verbally. It is likely that providers address these elements in practice, but do so only verbally. In contrast, whereas some elements were omitted, mostly that information was not desired, suggesting that many elements may not be needed for inclusion in SCPs.

Literature pertaining to the delivery of survivorship care planning suggests that this occur at the end of treatment4,10,13; however, guidance from patients about the optimal timing is lacking. Our study elucidates that for the majority of elements, education ought to be initiated at diagnosis and continue throughout the cancer care continuum, thus supporting the notion of an SCP evolving over time.33,34

Our study has limitations. First, we relied on self-report that may be susceptible to recall bias and thus not be a direct measure of the actual information provided. Nonetheless, patients' perceptions are important indicators of the information received and desired. Second, our sample was limited to patients who were mostly white, well educated, of above-average means who received care at an academic cancer center with an existing survivorship program. As such, our results may not be generalizable.

Despite limitations, we make important contributions to the survivorship literature by focusing on survivors of lymphoma, GI, and head and neck cancers, reporting survivors' receipt of recommended elements of care and their preferences for information and timing. Our findings support recent literature proposing that standardized core elements presented during a clinical session may be a more optimal strategy for providing essential components of cancer survivorship care.35,36 Although others have reported the lack of information provided to survivors, our assessment about the desired timing of information is (to our knowledge) novel, though consistent with a recent article by Haq et al,37 who found that information needs of patients evolve and do not follow a set chronology from diagnosis through follow-up.

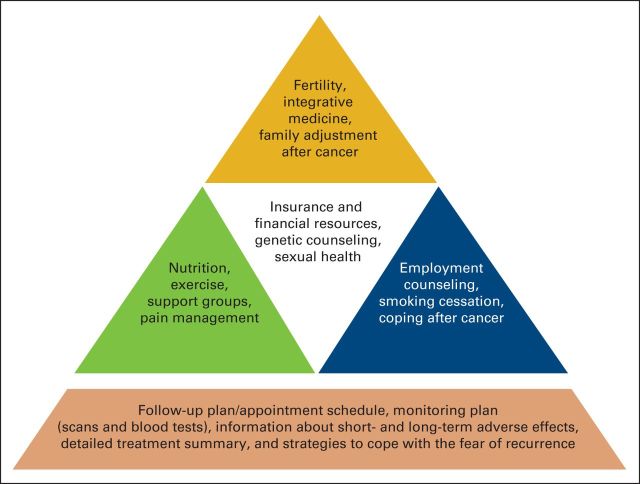

On the basis of our study findings, we propose a two-tier system to provide patient-centered survivorship planning content. The first tier would deliver a follow-up plan/appointment schedule, a monitoring plan (scans and blood tests), short- and long-term adverse effects information, a treatment summary, and strategies to cope with the fear of recurrence to all cancer survivors. This core would provide the foundation that would allow for a second tier of content to be distributed by providers only if and when the element was identified by the individual survivor as personally desired. We propose a model (Figure 1) that may be used to prioritize the elements of survivorship care planning.

Figure 1.

Essential elements hierarchy of patient needs in cancer survivorship.

Our study suggests that comprehensive survivorship care planning may not be optimal, and that survivors may be better served by being provided with individualized information at the desired time. Whereas the IOM focused on survivors being “lost in transition” after treatment, survivorship needs appear to arise at the time of diagnosis. Clinicians must identify individual needs, address them early, and continue to revisit them during the cancer care continuum.

Acknowledgment

Supported by the LIVESTRONG Foundation. Previously presented in part at the Sixth Biennial Cancer Survivorship Research Conference, “Cancer Survivorship Research: Translating Science to Care,” Arlington, VA, June 14-16, 2012, and at the New England Cancer Survivorship Research Symposium, Boston, MA, May 1, 2013.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Richard Boyajian, Amy Grose, Nina Grenon, Kristin Roper, Karen Sommer, Michele Walsh, Anna Snavely, Susan Neary

Administrative support: Ann Partridge

Collection and assembly of data: Richard Boyajian, Amy Grose, Nina Grenon, Kristin Roper, Michele Walsh, Anna Snavely, Susan Neary, Larissa Nekhlyudov

Data analysis and interpretation: Richard Boyajian, Anna Snavely, Ann Partridge, Larissa Nekhlyudov

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1. Siegel R DeSantis C Virgo K , etal: Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012 CA-Cancer J Clin 62: 220– 241,2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harrington CB Hansen JA Moskowitz M , etal: It's not over when it's over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors-a systematic review Int J Psychiatry Med 40: 163– 181,2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA: Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer Cancer 112: 2577– 2592,2008. suppl 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stricker CT, Jacobs LA: Physical late effects in adult cancer survivors Oncology (WillistonPark) 22: 33– 41,2008. suppl 8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. ASCO's Library of Treatment Plans and Summaries Expands J Oncol Pract 6: 31– 36,2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for Patients. http://www.nccn.com/cancer-guidelines.html.

- 7.American College of Surgeons Cancer Program Standards 2012 Version 1.1: Ensuring Patient Centered Care, 9/12. http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.html.

- 8. Salz T Oeffinger KC McCabe MS , etal: Survivorship care plans in research and practice CA Cancer J Clin 62: 101– 117,2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blinder VS Norris VW Peacock NW , etal: Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment plan and summary documents in community oncology care Cancer 119: 164– 172,2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burg MA Lopez ED Dailey A , etal: The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients J Gen Intern Med 24: S467– S471,2009. suppl 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brennan ME Butow P Marven M , etal: Survivorship care after breast cancer treatment-experiences and preferences of Australian women Breast 20: 271– 277,2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hawkins NA Pollack LA Leadbetter S , etal: Informational needs of patients and perceived adequacy of information available before and after treatment of cancer J Psychosoc Oncol 26: 1– 16,2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roundtree AK Giordano SH Price A , etal: Problems in transition and quality of care: Perspectives of breast cancer survivors Support Care Cancer 19: 1921– 1929,2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kantsiper M McDonald EL Geller G , etal: Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: Perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers J Gen Intern Med 24: S459– S466,2009. suppl 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baravelli C Krishnasamy M Pezaro C , etal: The views of bowel cancer survivors and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up J Cancer Surviv 3: 99– 108,2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beckjord EB Arora NK McLaughlin W , etal: Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: Implications for cancer care J Cancer Surviv 2: 179– 189,2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hewitt ME Bamundo A Day R , etal: Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: Qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians J Clin Oncol 25: 2270– 2273,2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marbach TJ, Griffie J: Patient preferences concerning treatment plans, survivorship care plans, education, and support services Oncol Nurs Forum 38: 335– 342,2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miller R: Implementing a survivorship care plan for patients with breast cancer Clin J Oncol Nurs 12: 479– 487,2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Snyder CF Frick KD Kantsiper ME , etal: Prevention, screening, and surveillance care for breast cancer survivors compared with controls: Changes from 1998 to 2002 J Clin Oncol 27: 1054– 1061,2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Snyder CF Earle CC Herbert RJ , etal: Trends in follow-up and preventive care for colorectal cancer survivors J Gen Intern Med 23: 254– 259,2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruddy KJ, Partridge AH: Fertility (male and female) and menopause J Clin Oncol 30: 3705– 3711,2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higano CS: Sexuality and intimacy after definitive treatment and subsequent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer J Clin Oncol 30: 3720– 3725,2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bober SL, Varela VS: Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: Challenges and intervention J Clin Oncol 30: 3712– 3719,2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stubblefield MD McNeely ML Alfano CM , etal: A prospective surveillance model for physical rehabilitation of women with breast cancer Cancer 118: 2250– 2260,2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wolin KY, Colditz GA, Proctor EK: Maximizing benefits for effective cancer survivorship programming: Defining a dissemination and implementation plan Oncologist 16: 1189– 1196,2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kent EE Arora NK Rowland JH , etal: Health information needs and health-related quality of life in a diverse population of long-term cancer survivors Patient Ed Couns 89: 345– 352,2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moffatt S, Noble E, White M: Addressing the financial consequences of cancer: Qualitative evaluation of a welfare rights advice service PLoS One 7: e42979,2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Neumark D: Breast cancer survival, work, and earnings J Health Econ 21: 757– 779,2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R: Cancer survivors in the United States: Age, health, and disability J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58: 82– 91,2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deimling GT Bowman KF Sterns S , etal: Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors Psychooncology 15: 306– 320,2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stricker CT Jacobs LA Risendal B , etal: Survivorship care planning after the Institute of Medicine recommendations: How are we faring? J Cancer Surviv 5: 358– 370,2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Horning SJ: Follow-up of adult cancer survivors: New paradigms for survivorship care planning Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 22: 201– 210,2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Earle CC, Ganz PA: Failing to plan is planning to fail: Improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans J Clin Oncol 24: 5112– 5116,2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ganz PA, Earle CC, Goodwin PJ: Cancer survivorship care: Don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good J Clin Oncol 30: 3655– 3656,2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oeffinger KC Hudson MM Mertens AC , etal: Increasing rates of breast cancer and cardiac surveillance among high-risk survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma following a mailed, one-page survivorship care plan Pediatr Blood Cancer 56: 818– 824,2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haq R Heus L Baker NA , etal: Designing a multifaceted survivorship care plan to meet the information and communication needs of breast cancer patients and their family physicians: Results of a qualitative pilot study BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 13: 76,2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]