Abstract

Background

Acetoin, especially the optically pure (3S)- or (3R)-enantiomer, is a high-value-added bio-based platform chemical and important potential pharmaceutical intermediate. Over the past decades, intense efforts have been devoted to the production of acetoin through green biotechniques. However, efficient and economical methods for the production of optically pure acetoin enantiomers are rarely reported. Previously, we systematically engineered the GRAS microorganism Corynebacterium glutamicum to efficiently produce (3R)-acetoin from glucose. Nevertheless, its yield and average productivity were still unsatisfactory for industrial bioprocesses.

Results

In this study, cellular carbon fluxes in the acetoin producer CGR6 were further redirected toward acetoin synthesis using several metabolic engineering strategies, including blocking anaplerotic pathways, attenuating key genes of the TCA cycle and integrating additional copies of the alsSD operon into the genome. Among them, the combination of attenuation of citrate synthase and inactivation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase showed a significant synergistic effect on acetoin production. Finally, the optimal engineered strain CGS11 produced a titer of 102.45 g/L acetoin with a yield of 0.419 g/g glucose at a rate of 1.86 g/L/h in a 5 L fermenter. The optical purity of the resulting (3R)-acetoin surpassed 95%.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest titer of highly enantiomerically enriched (3R)-acetoin, together with a competitive product yield and productivity, achieved in a simple, green processes without expensive additives or substrates. This process therefore opens the possibility to achieve easy, efficient, economical and environmentally-friendly production of (3R)-acetoin via microbial fermentation in the near future.

Keywords: (3R)-Acetoin, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Metabolic engineering, Microbial fermentation, Citrate synthase, Green chemistry

Background

Acetoin (3-hydroxy-2-butanone) is a popular food additive with a pleasant butter-like flavor [1]. Since it can be obtained from biomass and possesses reactive carbonyl and hydroxyl moieties, the United States Department of Energy designated acetoin as one of 30 promising platform chemicals that were given priority for development and utilization in 2004 [2]. Acetoin is chiral, and its enantiomers (3S)- and (3R)-acetoin are more valuable than the racemate as they are potential pharmaceutical intermediates [3]. Moreover, they can be used to synthesize liquid crystal materials and novel optically active α-hydroxyketone derivatives [4].

At present, the commercial production of acetoin is mostly based on chemical methods with many disadvantages, such as high cost, high pollution, and low yield [5]. Moreover, the use of chemosynthetic, non-natural acetoin in food and cosmetics is restricted due to safety concerns [6, 7]. The biotechnological production of safe and natural acetoin could be more ecological and sustainable than their chemical counterparts [8, 9]. These methods, including microbial fermentation [8, 10, 11], whole-cell biocatalysis [12, 13] and enzymatic biocatalysis [14, 15], have consequently gained great attention over the past decades. Saccharomyces cerevisiae JHY617-SDN was able to efficiently accumulate 100.2 g/L acetoin from glucose during fed-batch fermentation [16]. Gluconobacter oxydans NL71 could produce 165.9 g/L acetoin from 2,3-butanediol in a whole-cell catalysis process [17]. This is the highest acetoin titer ever reported. However, the enantiomeric excess of the produced acetoin was not reported, and efficient methods for the production of optically pure (3R)-acetoin were rarely reported. Nevertheless, some representative publications with good results do exist. Using a two-enzyme coupling system, 12.2 g/L of optically pure (3S)-acetoin was efficiently produced from diacetyl with a high productivity of 9.76 g/L/h [18]. By constructing an efficient E. coli whole-cell biocatalyst, Guo et al. [19] obtained a high (3R)-acetoin titer of 86.7 g/L from optically pure (R,R)-2,3-butanediol. However, the expensive chiral substrate, and the complicated, costly processing steps, such as protein purification through Ni–NTA affinity chromatography or centrifugation to concentrate the catalyst cells, made it economically unfeasible in industrial applications.

Acetoin production from petrochemicals such as the expensive chiral 2,3-bantediol or the noxious diacetyl is costly and unsustainable. Consequently, (3R)-acetoin production from renewable substrates via microbial fermentation is highly favored in recent studies. Many microorganisms can naturally synthesize optically pure (3R)-acetoin, including Klebsiella pneumoniae [20], Serratia marcescens [21, 22], Lactococcus lactis [23] and Bacillus sp. [24]. When the acetoin degradation pathway was disrupted, the Klebsiella pneumoniae strain ΔbudCΔaco was able to accumulate 62.3 g/L (3R)-acetoin in 57 h [20]. However, this pathogenic microorganism can be hazardous to humans, which entails unacceptable safety risks in industrial-scale production. Dai et al. [25] isolated the marine strain Bacillus subtilis CGMCC 13141 capable of producing 83.7 g/L of (3R)-acetoin with a high yield of 0.447 g/g glucose in fed-batch fermentation. However, the titer was still insufficient for industrial demands.

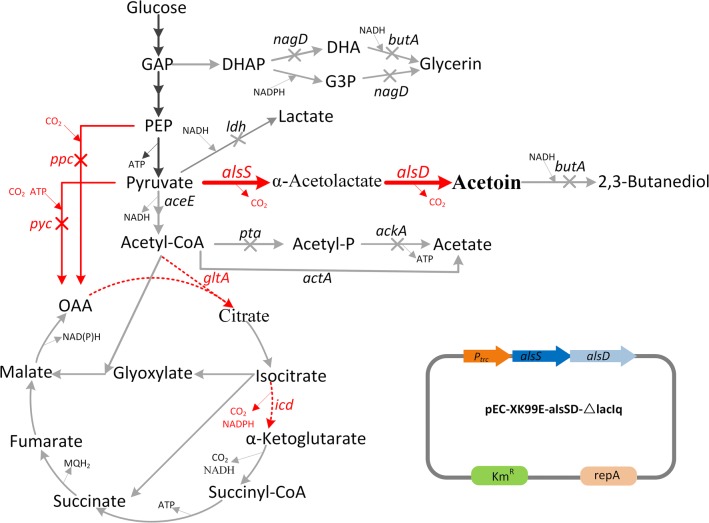

In our previous study [26], we systematically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum, the famous amino acids industrial workhorse with GRAS (generally recognized as safe) status, to develop a safe and efficient industrial (3R)-acetoin producer. The best strain CGR7 was able to produce 96.2 g/L (3R)-acetoin with an optical purity of more than 95% in fed-batch mode with a yield of 0.360 g/g glucose and productivity of 1.30 g/L/h [9], highlighting C. glutamicum as a competitive producer of enantiopure acetoin with fantastic potential for industrial-level production. While this was still the highest reported titer at the time of writing, the corresponding yield (73.5% of the theoretical value) and average productivity were still unsatisfactory for economical production. In this study, the previously engineered strain CGR6 (ATCC13032 ∆pta∆ackA∆ldh∆butA∆nagD; ∆ackA::Ptuf -alsSD) [9] was chosen as a chassis for further optimization. In this strain, the biosynthesis pathways of the major by-products lactate, glycerin, and acetate, as well as the downstream product 2,3-butanediol were disrupted to increase the pool of the precursor pyruvate and prevent acetoin from being reduced to downstream 2,3-butanediol. Moreover, a copy of the acetoin synthesis operon alsS-alsD under the control of the strong constitutive promoter Ptuf, was inserted into the locus of the deleted gene ackA to enhance acetoin production. Here, several strategies were successively applied to redirect more carbon flux toward acetoin synthesis in strain CGR6, including interdicting anaplerotic pathways, weakening key genes of the TCA cycle, and inserting additional copies of the alsSD operon into the genome of the host. The optimal engineered strain CGS11 (Fig. 1) achieved a titer of 102.45 g/L acetoin with a yield of 0.419 g/g glucose at a rate of 1.86 g/L/h in fed-batch fermentation.

Fig. 1.

The (3R)-acetoin biosynthesis pathway of C. glutamicum. Genes manipulated in this study are indicated in red. The bold arrows indicate metabolic fluxes increased by overexpression of the corresponding genes. The gray arrows indicate the reactions leading to a byproduct or presumably irrelevant reactions. Deleted genes are indicated with crosses. Downregulated genes are indicated with dashed arrows. Abbreviations: GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; DHA, dihydroxyacetone; G3P, sn-glycerol 3-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; OAA, oxaloacetate. Genes and their encoded enzymes: alsS, acetolactate synthase; alsD, acetolactate decarboxylase; ppc, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; pyc, pyruvate carboxylase; icd, isocitrate dehydrogenase; gltA, citrate synthase. pta, phosphotransacetylase; ackA, acetate kinase; aceE, E1 component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; nagD, putative phosphatase; butA, 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase

Materials and methods

Reagents, strains and media

Primers were synthesized by GENEWIZ (Suzhou, China). Plasmids were extracted using the Axyprep™ Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Axygen, USA) and the SanPrep Column Plasmid Mini-Prep Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). BHI Broth was purchased from Hopebio (Qingdao, China). Yeast extract was purchased from Angel (Hubei, China). Acetoin, creatine, 1-naphthol, ethyl 2-acetoxy-2-methylacetoacetate, oxaloacetate and 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic) acid were purchased from Sigma (Merck, USA). The 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine standard was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). Other reagents were purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

The strains and plasmids used in this study were listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli DH5α was used for plasmid construction and was grown in lysogeny broth (LB) medium containing (per liter) 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g NaCl. Brain heart infusion (BHI) medium was used for the transformation and tube culture of C. glutamicum. CGIII medium composed of (per liter) 10 g tryptone, 10 g yeast extract, 2.5 g NaCl and 20 g glucose was used for pre-cultures of C. glutamicum. Batch fermentation of acetoin was conducted in CGXIIP medium containing (per liter): 10 g yeast extract, 5 g (NH4)2SO4, 5 g urea, 1 g KH2PO4, 1 g K2HPO4, 0.25 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g CaCl2, 0.01 g FeSO4·7H2O, 0.1 mg MnSO4·H2O, 1 mg ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.2 mg CuSO4·5H2O, 0.02 mg NiCl·6H2O, 0.4 mg biotin and 38 g glucose, pH 7.0. Fed-batch fermentation was conducted in LBRC medium containing (per liter): 10 g yeast extract, 50 g corn steep liquor, 1 g urea, 0.5 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O and 2 g sodium acetate, supplemented with the indicated amount of glucose, pH 7.0. The stock comprising 1000 g/L glucose used for fed-batch fermentation, was prepared by putting 100 g glucose and 36 mL ddH2O in a Schott-Duran bottle and sterilizing at 110 °C for 10 min, then stored at 60 °C. Antibiotics were added where appropriate as follows: for C. glutamicum, kanamycin 25 mg/L, for E. coli, kanamycin 40 mg/L.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Relevant characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | Host for plasmid cloning | Invitrogen |

| ATCC 13032 |

C. glutamicum wild type Biotin auxotrophic |

ATCCa |

| CGR6 | ATCC13032∆pta∆ackA∆ldh∆butA∆nagD, ∆ackA::Ptuf -alsSD | [9] |

| CGS1 | CGR6 ∆ppc | This study |

| CGS2 | CGR6 ∆pyc | This study |

| CGS3 | CGR6 ∆ppc∆pyc | This study |

| CGS4 | CGS3 ICDA94D | This study |

| CGS5 | CGS3 ICDG407S | This study |

| CGS6 | CGS3 ICDR453S | This study |

| CGS7 | CGR6 P1-gltA | This study |

| CGS8 | CGS1 P1-gltA | This study |

| CGS9 | CGS8 ∆butA::Ptuf -alsSD, ∆nagD::Ptuf -alsSD | This study |

| CGS11 | CGS9 pEC-XK99E-alsSD-∆lacIq | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pD-sacB | KanR; vector for in-frame deletion (sacBB.sub.; lacZα; OriVE.c.) | [56] |

| pD-sacB-ppc | pD-sacB carrying the flanking sequences of the ppc gene | This study |

| pD-sacB-pyc | pD-sacB carrying the flanking sequences of the pyc gene | This study |

| pD-sacB-butA | pD-sacB carrying the flanking sequences of the butA gene | [41] |

| pD-sacB-nagD | pD-sacB carrying the flanking sequences of the nagD gene | [9] |

| pD-sacB-icd-mut-1 | KanR, containing the nucleotide sequence for ICD amino acid exchange A94D | This study |

| pD-sacB-icd-mut-2 | KanR, containing the nucleotide sequence for ICD amino acid exchange G407S | This study |

| pD-sacB-icd-mut-3 | KanR, containing the nucleotide sequence for ICD amino acid exchange R453S | This study |

| pD-sacB-P1-gltA | KanR, containing P1 promoter and gltA flanks | Unpublished work |

| pD-sacB-butA-alsSD | KanR, containing Ptuf -alsSD flanks | This study |

| pD-sacB-nagD-alsSD | KanR, containing Ptuf -alsSD flanks | This study |

| pEC-XK99E | KanR; C. glutamicum/E. coli shuttle vector (Ptrc, lacIq; pGA1, OriVC.g., OriVE.c.) | [57] |

| pEC-XK99E-alsSD-ΔlacIq | Derived from pEC-XK99E, for the overexpression of alsS and alsD under promoter Ptrc | [9] |

a ATCC, American Type Culture Collection

Construction of plasmids and strains

All the primers used in this study are listed in supplementary Additional file 1: Table S1. All DNA manipulations, including restriction enzyme digestion and vector isolation were carried out using standard protocols [27]. The suicide plasmid pD-sacB was used for genome editing in C. glutamicum via two-step homologous recombination [28].

To delete the pyc gene, the vector pD-sacB-pyc was constructed as follows: the upstream sequence of pyc and a pyc-specific fragment were amplified from C. glutamicum genomic DNA by PCR using the primer pairs pyc-1/pyc-2 and pyc-3/pyc-4, respectively, and fused by PCR. The resulting product was digested with BamHI and SalI and ligated between the corresponding sites of pD-sacB. The plasmid pD-sacB-ppc was constructed analogously, using BamHI and HindIII.

To introduce mutations into the endogenous gene icd, the plasmid pD-sacB-icd-mut-1 was constructed as follows: the flanking regions of the icd gene with relevant modifications were amplified from genomic DNA of C. glutamicum using the primer pairs ICDA94D-1/ICDA94D-2 and ICDA94D-3/ICDA94D-4. The corresponding flanking fragments were fused using ICDA94D-1/ICDA94D-4. The fused product was digested with BamHI and SalI and ligated between the corresponding sites of pD-sacB to construct pD-sacB-icd-mut-1. The plasmids pD-sacB-icd-mut-2 and pD-sacB-icd-mut-3 were constructed analogously, using SmaI and SalI.

To integrate additional copies of the acetoin operon into the chromosome, the plasmid pD-sacB-butA-alsSD was constructed as follows: the acetoin operon (alsS-alsD) was amplified from the genome of CGR6 using the primer pair BalsSD-1/BalsSD-2. The resulting fragment was digested with XhoI/SalI and ligated between the corresponding sites of pD-sacB-butA. The plasmid pD-sacB-nagD-alsSD was constructed analogously.

Fermentation conditions

To prepare C. glutamicum pre-cultures, single colonies were used to inoculate 5 mL of BHI medium and grown at 30 °C and 220 rpm overnight, after which the entire resulting culture was used to inoculate 50 mL of CGIII medium, and grown to an OD600 of 10. For batch fermentation, the seed culture was used to inoculate a 250-mL shake flask containing 50 mL of CGXIIP medium to an initial OD600 of 1 and grown at 30 °C and 220 rpm on a rotary shaker.

For fed-batch fermentation, 100 mL of LBRC seed culture was used to inoculate a 5-L fermenter (Bailun, Shanghai, China) containing 1.8 L of LBRC medium. All cultivations were carried out at 30 °C with an aeration rate of 1 vvm. The agitation speed was maintained at 600 rpm. The initial pH of the medium was 6.5. During the fermentation process, the pH value was not controlled. The initial glucose concentration was 50 g/L, and an appropriate amount of 1000 g/L glucose stock was added to maintain its concentration between 10 and 50 g/L.

Analytical methods

The biomass concentration was calculated from OD600 values using an experimentally determined correlation 1 OD600 unit is equal to 0.25 g/L cell dry weight (CDW) [29]. Glucose was measured using an SBA Bio-analyzer (Shandong Academy of Sciences, China) after appropriate dilution. Metabolite concentrations were determined by HPLC, using an HPX-87H (300 mm × 7.8 mm) organic acid and sugar analysis column (Bio-Rad, China), kept at 60 °C, and a refractive index detector. The injection volume was 10 μL, and the mobile phase consisted of 5 mM H2SO4 at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The concentration of 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine was analyzed by GC-FID (PERSEE, Beijing, China) equipped with an HP-5 (19091 J-413, 30 m × 0.32 mm) capillary column (Agilent, USA) as described previously [30]. The optical purity of acetoin was determined by GC as described previously [9]. The fermentation broth was quenched by 40% pre-cooled (− 40 °C) methanol and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 1 min immediately to harvest cells, then resuspended cells with extracting solution provided by the Pyruvate Assay Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and disrupted cells by ultrasonication. The reaction, including the construction of pyruvate standard curves, was carried out using the Pyruvate Assay Kit.

Enzyme activity assays

Cells of the engineered strains were grown to the middle exponential phase (12 h) and late exponential phase (22 h), after which the fermentation broth was centrifuged at 5000×g for 10 min to harvest cells, which were washed twice with 1 mL 200 mM phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.0) and then resuspended in 0.3 mL of the same buffer. The cells were disrupted by ultrasonication and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 5000×g and 4 °C for 10 min. Enzyme activity was assayed in the resulting supernatant. Total protein concentrations were determined according to the Bradford method [31]. The formed amount of acetoin generated by acetolactate was measured to determine the acetolactate synthase (ALS) activity as described previously [32]. The acetolactate decarboxylase (ALDC) activity was assayed by measuring the production of acetoin as described previously [33]. The citrate synthase activity was determined by measuring the amount of CoA formed as described previously [34].

Results and discussion

Improvement of acetoin production by deleting ppc/pyc to reduce succinate accumulation

To analyze the carbon distribution in strain CGR6, batch fermentation in flasks was carried out. As shown in Fig. 2a, CGR6 was able to produce 11.30 g/L acetoin when glucose was almost depleted at 24 h, corresponding to a yield of 0.302 g/g glucose. As expected, no 2,3-butandiol or lactate was detected, since their synthesis pathways were blocked. Although 0.52 g/L α-ketoglutarate was detected when fermenting this strain in CGXIIY medium [9], it was not detected in CGXIIP medium in this study. The major by-product was succinate, with a titer of 2.63 g/L, followed by acetate (1.12 g/L) and glycerin (0.23 g/L). In our previous work, two key genes of succinate synthesis, ppc encoding phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase and pyc encoding pyruvate carboxylase, were respectively deleted via one-step homologous recombination (single crossover) with a tetracycline resistance marker [9]. The ppc/pyc-deficient strain showed an improved acetoin production in batch fermentation in flasks. However, the use of the tetracycline resistance marker impeded further genetic manipulation and was not acceptable for an industrial producer. In this study, we deleted the ppc and pyc genes in CGR6 using a markerless two-step recombination method (double crossover) [35], resulting in the strains CGS1 and CGS2, respectively.

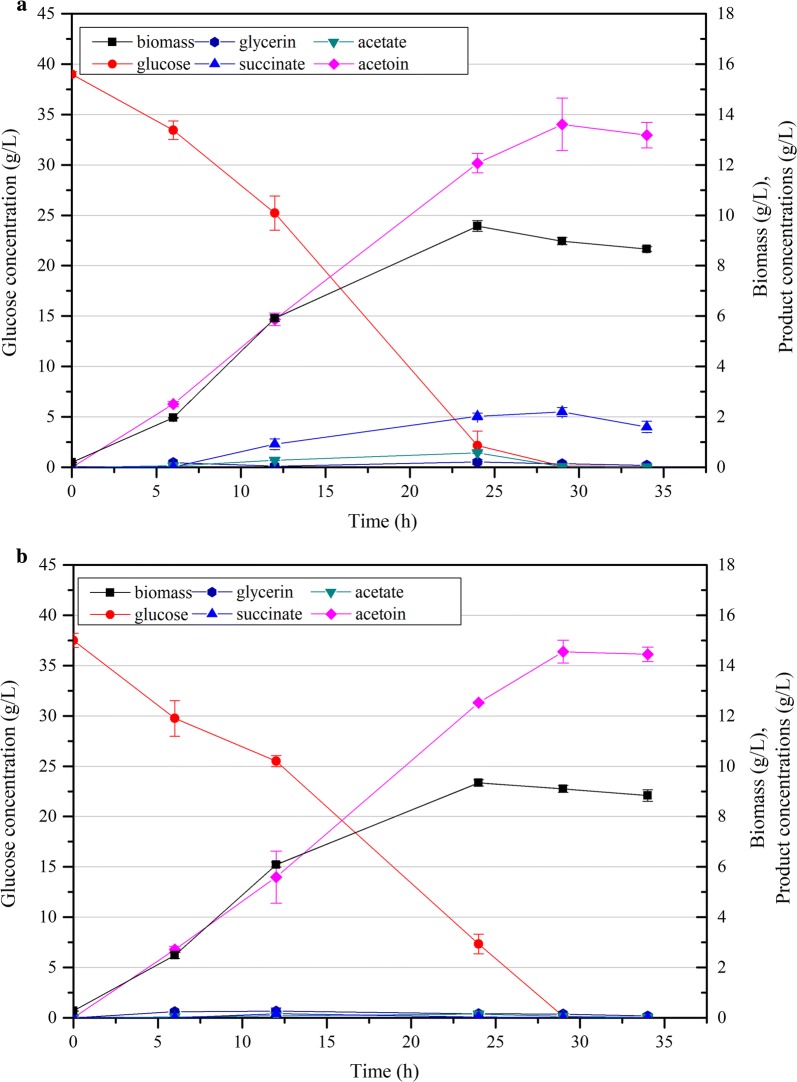

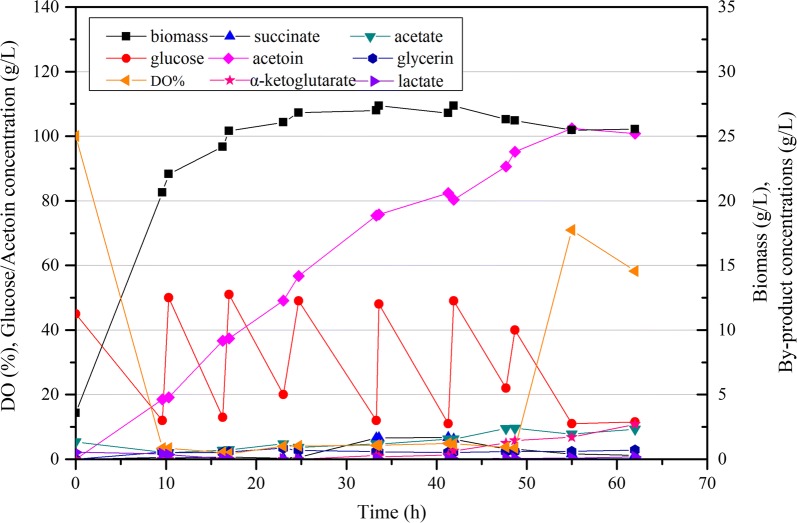

Fig. 2.

Time profiles of the biomass (g/L), glucose, organic acid and acetoin concentrations of strains CGR6 (a), CGS1 (b) and CGS2 (c) cultured with 38 g/L glucose. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from three independent cultures

As shown in Fig. 2b, succinate production was almost completely abolished in the ppc knockout strain CGS1, with a titer of only 0.03 g/L. The glucose consumption rate of CGS1 was decreased compared with that of CGR6, and 11.96 g/L of acetoin was obtained when glucose was exhausted at 29 h. This corresponds to a yield of 0.328 g/g glucose, which was 9.3% higher than that of CGR6. By contrast, the succinate production in the pyc knockout strain CGS2 was almost unchanged (Fig. 2c), but its acetoin production was enhanced with a titer of 11.75 g/L when glucose was depleted at 29 h, and a yield of 0.323 g/g glucose. The glucose consumption rate of CGS2 was also decreased compared with that of CGR6, but it was somewhat higher than that of CGS1 at 24 h.

Mutants deficient in ppc rather than pyc could efficiently reduce succinate accumulation, indicating that PEP rather than pyruvate is the key precursor of succinate under aerobic conditions. In agreement with previous reports [36, 37], the growth of CGS1 and CGS2 was only mildly decreased, but their acetate titers (respectively 0.06 and 0.44 g/L) were unexpectedly significantly decreased compared with that of CGR6 (1.12 g/L) (Table 2). We suspected that the reduced acetate accumulation in CGS1 and CGS2 was resulted from the decreased glucose consumption rates (Table 2), which can reduce the flux in overflow metabolism. The only another detected by-product was glycerin, with a titer of about 0.30 g/L in both CGS1 and CGS2. The two strains both showed improved acetoin yields, which was consistent with our previous results [9]. However, strain CGS3 with ppc and pyc-deficient was unable to grow on glucose in mineral medium and still grew poorly with 10 g/L yeast extract addition (data not shown), which was consistent with previous reports [37, 38]. After considering the acetoin titer, yield and by-products accumulation, strain CGS1 was chosen for further manipulation.

Table 2.

Fermentation characteristics of C. glutamicum strains cultivated in CGXIIP medium supplemented with initial 38 g/L glucose measured at 24 h

| Strain | Biomass (g/L) | Consumed glucose (g/L) | Acetoin yield (g/g glucose) | Acetoin productivity (g/L/h) | Titer (g/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetoin | Acetate | Glycerin | Succinate | |||||

| CGR6 | 10.29 ± 0.27 | 37.42 ± 0.06 | 0.302 ± 0.009 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 11.30 ± 0.26 | 1.12 ± 0.14 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 2.63 ± 0.15 |

| CGS1 | 10.19 ± 0.03 | 32.54 ± 0.59 | 0.309 ± 0.005 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 10.06 ± 0.26 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| CGS2 | 10.18 ± 0.11 | 33.50 ± 1.39 | 0.326 ± 0.020 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 10.91 ± 0.86 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 2.67 ± 0.22 |

| CGS5 | 8.67 ± 0.34 | 24.55 ± 1.08 | 0.272 ± 0.009 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 6.68 ± 0.54 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | <0.01 |

| CGS7 | 9.58 ± 0.21 | 35.84 ± 1.43 | 0.337 ± 0.011 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 12.07 ± 0.38 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 2.02 ± 0.13 |

| CGS8 | 9.34 ± 0.12 | 30.17 ± 0.98 | 0.415 ± 0.005 | 0.52 ± 0.01 | 12.53 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

| CGS9 | 7.88 ± 0.45 | 24.45 ± 1.52 | 0.484 ± 0.015 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 11.83 ± 0.35 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

| CGS11 | 8.06 ± 0.44 | 24.54 ± 0.46 | 0.497 ± 0.005 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 12.22 ± 0.20 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

Error bars indicate the standard deviations from three independent cultures

Improvement of acetoin production by blocking anaplerotic pathways and introducing isocitrate dehydrogenase mutants

Most studies on improving precursor pyruvate (Fig. 1) availability focused on complete inactivation or attenuation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC) by deleting the aceE gene or reducing its promoter activity [39, 40]. In our previous work, the aceE gene was also deleted to conserve pyruvate and improve acetoin production. However, additional acetate was required for cell growth and the best strain CGL3 (C. glutamicum ∆aceE∆ldh∆butA; pEC-XK99E-alsSD) could only accumulate 8.33 g/L acetoin from about 33 g/L glucose and 10 g/L acetate under optimal conditions [41]. In cases of attenuating PDHC, although the growth of the resulting strain was independent of acetate addition, the cell growth and glucose consumption rate were dramatically reduced [39]. Therefore, deletion or attenuation of PDHC might not be optimal for manufacturing optically pure (3R)-acetoin.

A double deletion of ppc and pyc is generally lethal for C. glutamicum due to a lack of oxaloacetate [37]. However, a novel strategy for improving the biosynthesis of pyruvate-derived metabolites by introducing newly identified isocitrate dehydrogenase mutants (A94D, G407S or R453S) was recently proposed [38]. These icd mutations both lowered the ICD activity and activated the glyoxylate shunt, and were consequently able to recover oxaloacetate re-supply and cell growth of C. glutamicum ∆ppc∆pyc [38]. Thus, three ICD mutants A94D, G407S and R453S were introduced into CGS3 to test their effects on acetoin production, resulting in strains CGS4, CGS5 and CGS6, respectively. As shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1, strains CGS4 and CGS6 showed almost the same growth inhibition as strain CGS3. This is probably because strain CGS3 is an acetoin producing host, in which the major carbon fluxes have already been redirected toward acetoin synthesis, and are therefore insufficient to support an activated glyoxylate shunt to re-supply oxaloacetate. Nevertheless, CGS5 with the mutant ICDG407S successfully recovered cell growth to some extent. However, acetoin production in CGS5 was dramatically decreased to a titer of only 11.37 g/L when glucose was exhausted at 34 h, and a yield of 0.280 g/g glucose, which was 14.6% lower than that of CGS1 (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). This indicated that the carbon fluxes from acetoin synthesis rather than its competing pathways were redirected to regain biomass synthesis, but the reason for this is still unknown.

Improvement of acetoin production by reducing citrate synthase activity

Since directly blocking acetyl-CoA or oxaloacetate synthesis severely affected the growth performance and failed to improve acetoin production, the focus of engineering was moved to citrate synthase (CS, encode by gltA), which condenses acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate to citrate and is one of the most important sinks for the flux of these two precursors. Therefore, reduction of CS activity was viewed as a promising strategy to lower the synthesis of acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate, and thereby conserve pyruvate for improved acetoin production. C. glutamicum mutants devoid of CS were unable to grow on glucose [34]. Therefore, a reduction rather than inactivation of CS activity was preferable. Moreover, regulation of the gltA gene, which is responsible for 95% of CS activity in C. glutamicum [42], was widely applied to improve the biosynthesis of pyruvate-derived products [34, 43–45]. However, the impact of reducing CS activity on acetoin production is still unclear. Therefore, we used a weak promoter P1 with approximately 1% activity of the Ptac [46] to replace the native promoter of gltA gene in CGR6 and CGS1, yielding strains CGS7 and CGS8 respectively.

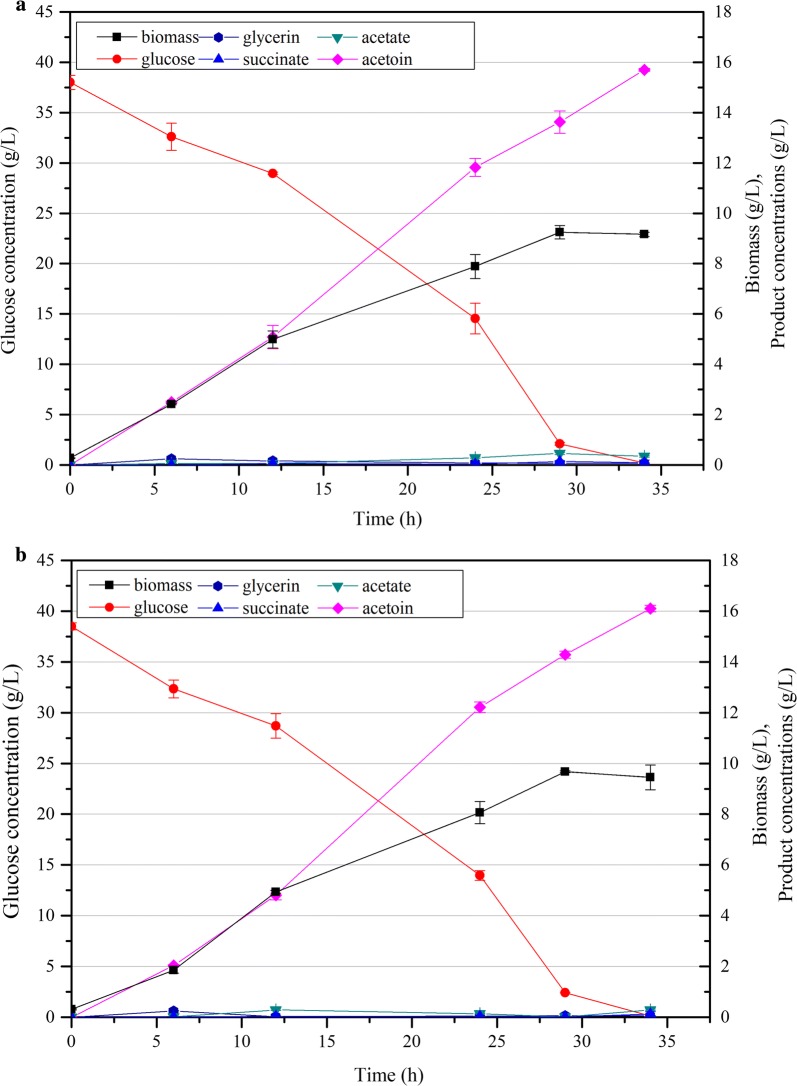

The strains’ CS activity was measured to confirm its successful downregulation. As shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S3A, the CS activity of CGS7 at 12 h in the middle exponential phase was 75.8% lower than that of CGR6, and 60.0% lower at 22 h in the late exponential phase. As shown in Table 2, the succinate yield of CGS7 at 24 h was 20.0% lower than that of CGR6 (0.056 versus 0.070 g succinate/g glucose). Moreover, the cell growth and glucose consumption were also decreased (Fig. 3a), suggesting that the flux into the TCA cycle was indeed reduced. Unexpectedly, the acetate yield decreased by 46.7% (0.016 versus 0.030 g acetate/g glucose). We speculated that the decreased glucose consumption rate in CGS7 would reduce the fluxes to acetate synthesis caused by overflow metabolism, and the newly available carbon fluxes flowed to acetoin effectively, leading to an increase of the acetoin yield at 24 h in contrast to CGR6 (0.337 versus 0.302 g acetoin/g glucose). Then, the yield further increased to 0.350 g/g glucose with a titer of 13.61 g/L when glucose was depleted at 29 h (Fig. 3a). However, the results indicated that neither weakening gltA nor the deletion of ppc could effectively improve the intracellular pyruvate pool, but a combination of both eventually led to a 31.1% increase of intracellular pyruvate (Additional file 1: Fig. S3B). At the same time, the acetoin production was significantly enhanced to 14.56 g/L, with a yield of 0.389 g/g glucose when glucose was exhausted at 29 h, which was 18.6% higher than that of CGS1 (Fig. 3b). While deletion of ppc obviously inhibited glucose consumption of CGS8 compared to CGS7 (Table 2), however, the acetoin productivity was 0.52 g/L/h at 24 h, even higher than that of CGS7 (0.50 g/L/h). Moreover, the by-products acetate (0.15 g/L), glycerin (0.17 g/L) and succinate (0.03 g/L) remained at low concentrations. After considering acetoin production and by-product accumulation, CGS8 was selected for further engineering.

Fig. 3.

Time profiles of the biomass (g/L), glucose, organic acid and acetoin concentrations of strains CGS7 (a) and CGS8 (b) cultured with 38 g/L glucose. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from three independent cultures

Furthermore, reduction of CS exhibited a fantastic synergistic effect on acetoin production with inactivation of PEP carboxylase, which is responsible for 90% of total oxaloacetate synthesis in C. glutamicum [47, 48]. As shown in Table 2, ppc knockout in CGS1 almost had no effect on acetoin yield (0.309 versus 0.302 g/g glucose), and gltA attenuation in CGS7 only led to a 11.6% increase in acetoin yield (0.337 versus 0.302 g/g glucose). However, the combination of the two gene modifications resulted in that the acetoin yield was significantly improved by 37.4% (0.415 versus 0.302 g/g glucose). The variations of intracellular pyruvate further confirmed the synergistic effect of CS and PEP carboxylase on acetoin production (Additional file 1: Fig. S3B), which would also be potential for improving other pyruvate-acetolactate-derived metabolites production.

Effect of enhancing the acetoin synthesis pathway on acetoin production

To further pull the carbon flux from pyruvate toward product accumulation, two additional alsSD operon (under the control of the constitutive promoter Ptuf) copies were inserted into the chromosome of CGS8 at the ∆butA and ∆nagD sites to generate the strain CGS9.

The activities of ALS and ALDC were listed in Table 3. The ALS activity of CGS9 was 2.33-fold higher than that of CGR6 at 12 h in the middle log phase, and subsequently increased by 11.6% at 22 h in late log phase. However, the ALDC activity of CGS9 was increased by only 47.0% compared with that of CGR6 at 12 h. Then, it decreased by 15.1% at 22 h, but was still 37.3% higher than that of CGR6. With the increase of alsSD copies, the intracellular pyruvate concentration was slightly decreased by 8.2%. However, when glucose was exhausted at 34 h, 15.70 g/L acetoin was accumulated with a yield of 0.408 g/g glucose (Fig. 4a), which was merely 4.9% higher than that of CGS8. Therefore, the increased ALS and ALDC activity appeared to still be insufficient to increase acetoin production.

Table 3.

Enzyme activities of different C. glutamicum strains

| Strains | Middle log phase (12 h) | Late log phase (22 h) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS activity (U/mg) | ALDC activity (U/mg) | ALS activity (U/mg) | ALDC activity (U/mg) | |

| CGR6 | 0.511 ± 0.087 | 0.608 ± 0.067 | 0.521 ± 0.060 | 0.553 ± 0.045 |

| CGS9 | 1.192 ± 0.094 | 0.894 ± 0.044 | 1.330 ± 0.122 | 0.759 ± 0.054 |

| CGS11 | 8.242 ± 0.362 | 2.864 ± 0.127 | 6.383 ± 0.778 | 1.074 ± 0.035 |

Error bars indicate the standard deviations from three independent cultures

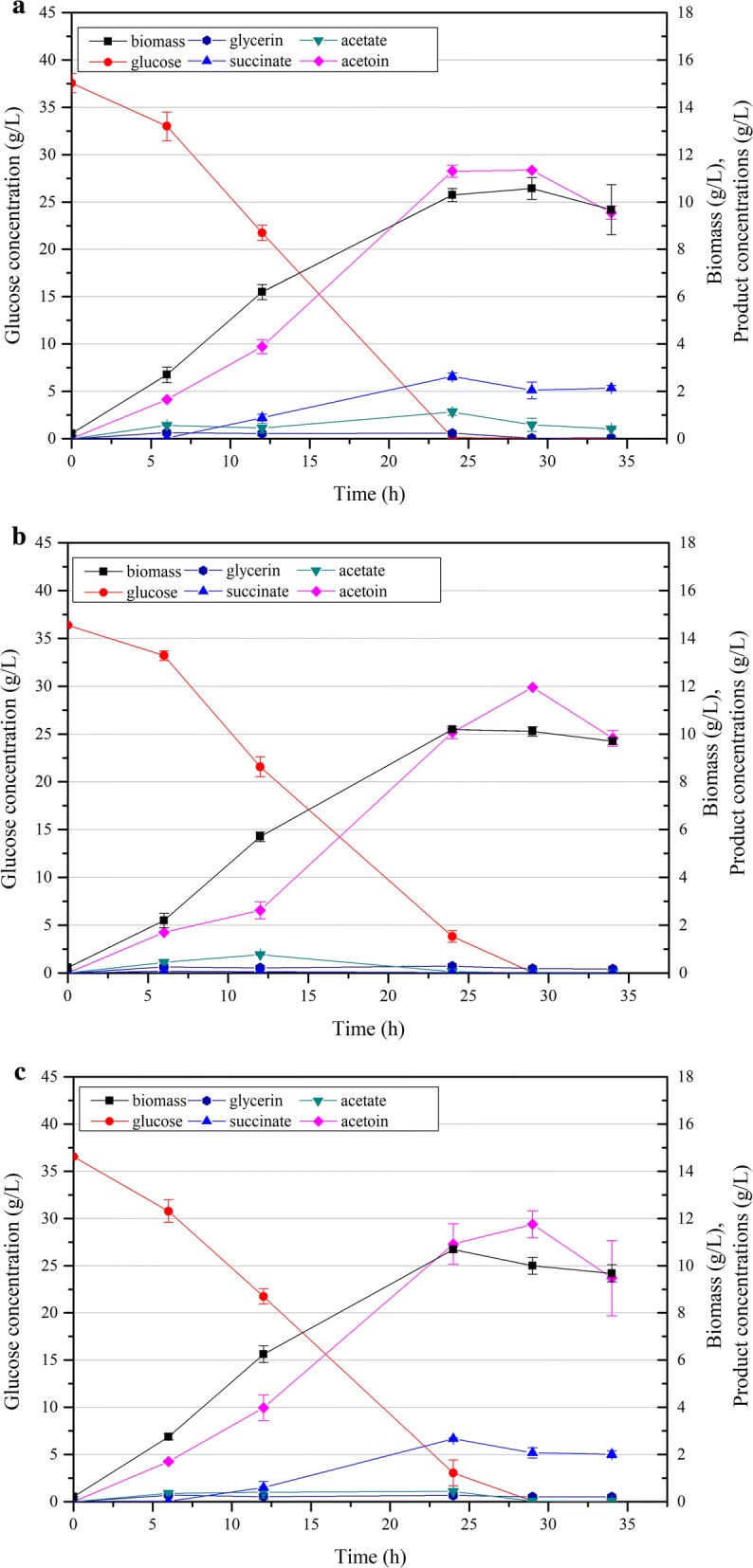

Fig. 4.

Time profiles of the biomass (g/L), glucose, organic acid and acetoin concentrations of strains CGS9 (a) and CGS11 (b) cultured with 38 g/L glucose. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from three independent cultures

To further pull pyruvate into acetoin synthesis pathway, the previously constructed alsSD over-expression plasmid pEC-XK99E-alsSD-ΔlacIq [9], was introduced into CGS9 to yield CGS11. Both the activities of ALS and ALDC were significantly improved compared with CGS9. Moreover, the intracellular pyruvate pool was further decreased by 6.7% compared with that of CGS9 (Additional file 1: Fig. S3B), indicating that more flux might have been re-directed toward acetoin synthesis. However, the acetoin production was still not obviously enhanced. When glucose was depleted at 34 h, the final acetoin titer was 16.10 g/L with a yield of 0.419 g/g glucose (Fig. 4b), which was only 7.7% higher than that of CGS8. Although the intracellular pyruvate pool of CGS11 was still 12.1% higher than that of CGR6, the carbon fluxes from pyruvate to competing pathways were successfully controlled as the titers of the main by-products, acetate (0.29 versus 1.12 g/L), glycerin (0.06 versus 0.23 g/L) and succinate (0.12 versus 2.63 g/L), were much lower than those of CGR6. No 2,3-butandiol or lactate was detected. Moreover, despite the decreases of cell growth and glucose consumption, the acetoin productivity was still comparable to that of strain CGS8. Therefore, strain CGS11 was a promising candidate for further scale-up fermentation.

Notably, both strain CGS9 and CGS11 showed much higher acetoin yields at 24 h (Table 2). The acetoin yield of strain CGS11 was even beyond the maximum theoretical yield of 0.489 g/g glucose and reached 0.498 g/g glucose at 24 h, which was mainly caused by the rich nutrients from the yeast extract in the CGXIIP medium. Moreover, all the detected by-products remained at low concentrations and biomass was relatively lower in CGS11 at 24 h (Table 2). Unexpectedly, the acetoin yield was then noticeably decreased to 0.419 g/g glucose at 34 h. The decreases of ALS and ALDC activities over time (Table 3) were initially suspected to be responsible for the decreased acetoin yield. However, the yields of by-products or biomass were not accordingly increased. Another possibility is that acetoin was re-used as an alternative carbon source when glucose was almost exhausted. Acetoin utilization is mainly catalyzed by the acetoin dehydrogenase (AoDH) complex [20, 49]. However, no candidate gene encoding a putative AoDH was identified in C. glutamicum through homologous sequence alignment (data not shown). Furthermore, acetoin degradation was more clearly observable when glucose was exhausted in fermentations of strains CGR6, CGS1 and CGS2 (Fig. 2a–c), but their biomass instead decreased during acetoin degradation. Thus, it did not appear that acetoin was consumed as a reserve carbon source, which would be expected to further support cell growth.

It is worth noting that two molecules of acetoin (C4H8O2) can be chemically converted to one molecule of 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine (TMP, C8H12N2, also called ligustrazine) in the presence of inorganic ammonium salts such as (NH4)2SO4 or diammonium phosphate [6, 30]. As shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S4, no TMP was accumulated in the fermentation broth of strain CGS11 at 24 h, but a titer of 1.27 g/L TMP was indeed detected at 34 h, which corresponded to a consumption of 1.64 g/L acetoin. Taking this portion of the generated acetoin into calculation, the yield could even reach a high level of 0.462 g/g glucose, which indicated that 94.4% of carbon fluxes had been directed toward acetoin synthesis.

Fed-batch fermentation of CGS11 for efficient (3R)-acetoin production

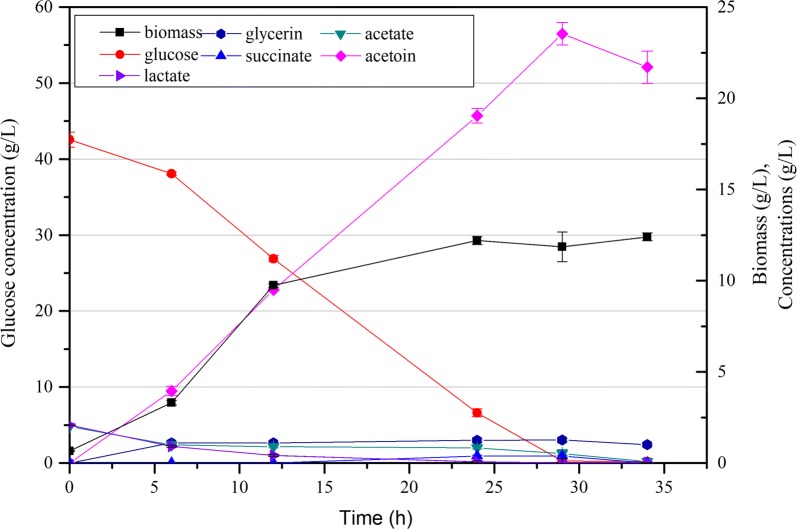

After considering the promising shake-flask results, strain CGS11 was chosen for fed-batch fermentation in order to evaluate its potential for further industrial application. Before scale-up production, CGS11 was evaluated in the LBRC medium, which was optimized for acetoin production in C. glutamicum in our previous work [9]. As shown in Fig. 5, the acetoin production was significantly enhanced with a titer of 23.53 g/L (3R)-acetoin and a yield of 0.553 g/g glucose when glucose was exhausted at 29 h. The acetoin production in CGS11 was also much higher than that in our previous optimal strain CGR7 (17.10 g/L (3R)-acetoin with a yield of 0.428 g/g glucose from LBRC medium) [9]. The rich nutrients such as lactate (initial 2.07 g/L) and amino acids from corn steep liquor (CSL) in LBRC medium should be the major reason for the improved acetoin production. And the remarkable effect on acetoin production with CSL addition was consistent with previous report in B. subtilis [50, 51]. Moreover, when using organic nitrogen source to replace inorganic nitrogen source (NH4)2SO4, no TMP was detected (Additional file 1: Fig. S4), which might be another reason for the improved acetoin production. Given that CSL is cheap and abundant, the cost caused by addition of CSL could be easily made up by the significant enhancement of acetoin production. The LBRC medium was therefore adopted for further fed-batch fermentation.

Fig. 5.

Time profiles of the biomass (g/L), glucose, organic acid and acetoin concentrations of strain CGS11 in LBRC medium in shake fermentation

During the fed-batch fermentation process, the cell growth, residual glucose, product concentrations and relative dissolved oxygen (DO) were determined. As shown in Fig. 6, a titer of 102.45 g/L acetoin was obtained at 55 h, corresponding to an average productivity of 1.86 g/L/h. The final fermentation volume was 2.45 L and a total of 625.85 g glucose was added in 7 batches, while the remaining glucose amount at 55 h was 11 g/L. Therefore, the acetoin yield was 0.419 g/g glucose, reaching 85.7% of the theoretical yield. The optical purity of the produced (3R)-acetoin surpassed 95% (Additional file 1: Fig. S5), which was consistent with our previous results [9]. No TMP was detected during the entire fed-batch fermentation (Additional file 1: Fig. S4). The final concentrations of acetate, succinate, glycerin and lactate were 1.94, 0.60, 0.41 and 0.33 g/L, respectively. However, α-ketoglutarate, which was undetectable during batch fermentation in shake flask, started to accumulate after 33 h and reached a final concentration of 1.71 g/L at 55 h. Nevertheless, all the by-products remained at acceptably low concentrations.

Fig. 6.

(3R)-acetoin production from glucose using CG11 in fed-batch fermentation. The strain was cultured in LBRC medium with initial 50 g/L glucose at 30 °C and 600 rpm in a 5-L fermenter under aeration of 1 vvm. A stock solution comprising 1000 g/L glucose was added when the glucose concentration dropped below 15 g/L to keep the glucose concentration between 10 and 50 g/L

We noticed that the glucose consumption and acetoin production were prone to stop when acetoin titer surpassed 100 g/L (from 55 to 62 h, as shown in Fig. 6). With an initial acetoin concentration of 80 g/L in shake fermentation, the specific growth rate of B. amyloliquefaciens was decreased by 99% [52], while wild-type B. subtilis 168 was even unable to grow on plates containing 50 g/L acetoin [53]. Therefore, the toxicity of the very high acetoin concentrations will no doubt prevent glucose assimilation and acetoin production of CGS11, and even activate its underlying acetoin catabolism. Since acetoin metabolism is complex and still not clearly elucidated, several successful strategies, such as physical/chemical mutagenesis [54], adaptive evolution [52, 53] or omics focusing on global transcriptional/metabolism level responses to acetoin stress [55], could be adopted to deeply understand and improve the acetoin tolerance of C. glutamicum in future studies.

To our best knowledge, the value of 102.45 g/L is the highest titer of highly enantiomerically enriched (3R)-acetoin reported to date (Table 4), as well as the best result obtained for acetoin production via microbial fermentation. Moreover, the yield and productivity were also good enough to merit further industrial application. Furthermore, the strains engineered in this work could also be used as platform strains to be further developed as microbial cell factories for production of (3S)-acetoin and chiral 2,3-butanediol.

Table 4.

Comparison of the production of acetoin via microbial fermentation process in the literature and in this study

| Strains/enzymes | Substrate | Titer (g/L) | Enantiomer | Yield (g/g) | Productivity (g/L/h) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production of optically pure acetoin | ||||||

| C. glutamicum CGS11 | Glucose | 102.45 | (3R)- | 0.419 | 1.86 | This study |

| C. glutamicum CGR7 | Glucose | 96.20 | (3R)- | 0.360 | 1.30 | [9] |

| Bacillus subtilis CGMCC 13141 | Glucose | 83.70 | (3R)- | 0.448 | 1.02 | [25] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Glucose | 62.30 | (3R)- | 0.140 | 1.09 | [20] |

| E. coli (pAC-NOX) | Glucose | 60.30 | (3R)- | 0.422 | 1.55 | [58] |

| Bacillus subtilis DL01 | Sugarcane molasses | 58.20 | (3R)- | 0.291 | 0.77 | [59] |

| Lactococcus lactis CS4701m | Glucose | 5.80 | (3S)- | 0.347 | 0.19 | [23] |

| Production of racemic acetoin (or optical purity not stated) | ||||||

| S. cerevisiae JHY617-SDN | Glucose | 100.10 | Ng | 0.440 | 1.82 | [16] |

| Gluconobacter oxydans DSM 2003 | 2,3-Butanediol | 89.20 | Ng | 0.891 | 1.24 | [60] |

| B. subtilis HS019 | Glucose | 82.50 | Ng | 0.460 | 1.33 | [53] |

| Bacillus licheniformis WX-02ΔbudCΔacoR | Glucose | 78.80 | Ng | 0.310 | 0.58 | [7] |

| S. marcescens H32-nox | Sucrose | 75.20 | Ng | 0.360 | 1.88 | [61] |

| Enterobacter aerogenes EJW-03 | Glucose | 71.70 | Ng | 0.320 | 2.87 | [62] |

| B. amyloliquefaciens E-11 | Glucose | 71.50 | Ng | 0.413 | 1.63 | [52] |

| B. licheniformis MW3 (△budC△gdh) | Glucose | 64.20 | Ng | 0.412 | 2.38 | [63] |

| B. subtilis ZB02 | Glucose, xylose, and arabinose | 62.20 | Ng | 0.288 | 0.86 | [64] |

| S. marcescens H32 | Sucrose | 60.50 | Ng | Ng | 1.44 | [65] |

| B. subtilis F126-2 | Glycerol | 60.48 | Ng | Ng | 1.26 | [66] |

| Lactococcus lactis CML B4 | Glucose | 59.00 | Ng | 0.360 | 2.11 | [67] |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa CJX518 | Glucose | 57.20 | Ng | 0.400 | 0.30 | [68] |

| B. subtilis TH-49 | Glucose | 56.90 | Ng | Ng | 0.89 | [69] |

| B. subtilis BMN | Glucose | 56.70 | Ng | 0.378 | 0.68 | [70] |

| P. polymyxa CS107 | Glucose | 55.30 | Ng | 0.370 | 1.32 | [71] |

| B. subtilis JNA-UD-6 | Glucose | 53.90 | Ng | 0.359 | 0.37 | [72] |

| Enterobacter cloacae SDM 45 | Glucose | 55.20 | Ng | 0.373 | 2.69 | [73] |

| Lignocellulosic hydrolysate | 45.60 | Ng | NG | 1.52 | ||

| B. amyloliquefaciens FMME044 | Glucose | 51.20 | Ng | 0.430 | 1.42 | [74] |

| Bacillus sp. H15-1. | Degermed maize flour hydrolysate | 50.80 | Ng | 0.285 | NG | [75] |

| C. glutamicum CGT2 | Glucose | 40.51 | Ng | 0.240 | 0.51 | [76] |

Ng indicates that the related information is Not Given

Conclusions

In summary, this is the first report on reducing CS activity to improve acetoin production. Moreover, combination of attenuation of CS and inactivation of PEP showed a significant synergistic effect on acetoin production. The highly engineered C. glutamicum strain CGS11 produced a titer of 102.45 g/L acetoin with a yield of 0.419 g/g glucose at a rate of 1.86 g/L/h in a 5 L fermenter, which is the highest titer of highly enantiomerically enriched (3R)-acetoin together with a competitive product yield and productivity, which opens the possibility of finally realizing the promises of industrial (3R)-acetoin production via green chemical process in the near future.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1 Primers used in this study. Fig. S1. Growth curves of strains CGS3, CGS4, CGS5, CGS6 and CGR6 in CGXIIY medium (per liter) containing 1 g yeast extract, 5 g (NH4)2SO4, 5 g urea, 1 g KH2PO4, 1 g K2HPO4, 0.25 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g CaCl2, 0.01 g FeSO4·7H2O, 0.1 mg MnSO4·H2O, 1 mg ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.2 mg CuSO4·5H2O, 0.02 mg NiCl·6H2O and 0.4 mg biotin and 40 g glucose, pH 7.0. Fig. S2. Time profiles of the biomass (g/L), glucose, organic acid and acetoin concentrations of strain CGS5 in CGXIIP medium. Fig. S3. (A) The activity of citrate synthase in CGR6 and CGS7. (B) The intracellular pyruvate concentrations of different strains at 12 h. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from three independent cultures. Fig. S4. Measurement of 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine concentrations by GC-FID. A: The 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine standard had a retention time of 10.598 min; B: Batch fermentation products of CGS11 in CGXIIP medium at 24 h; C: Batch fermentation products of CGS11 in CGXIIP medium at 34 h; D: Batch fermentation products of CGS11 in LBRC medium at 29 h; E: Fed-batch fermentation products of CGS11 in LBRC medium at 55 h. Fig. S5. Identification of acetoin enantiomers by GC-FID. A: The optically pure standards of (3R)- and (3S)- had retention times of 9.215 and 9.598 min, respectively; B: Fermentation products of CGS11 in CGXIIP medium; C: Fed-batch fermentation products of CGS11 in LBRC medium at 55 h.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

LL, YM, and TC conceived and designed the experiments. LL, MK, ZC, BJ and ZC performed the experiments. YM, LL, TC, ZW and HM analyzed the data. YM, LL and TC wrote and revised this manuscript. TC supervised the work. All authors contributed to the discussion of the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants NSFC-21576191, NSFC-21621004 and NSFC-21776208).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lingxue Lu and Yufeng Mao contributed equally to this work

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12934-020-01363-8.

References

- 1.Xiao Z, Lu JR. Generation of acetoin and its derivatives in foods. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:6487–6497. doi: 10.1021/jf5013902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werpy T, Petersen GE. Top value added chemicals from biomass. Washington, DC: Department of Energy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao Z, Xu P. Acetoin metabolism in bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2007;33:127–140. doi: 10.1080/10408410701364604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saito S IH, Ohno K: Alpha-hydroxyketone derivatives, liquid crystal compositions containing said derivatives, and liquid crystal devices using said compositions. US Patent, 5164112. 1992.

- 5.Gu L, Lu T, Li X, Zhang Y. A highly efficient thiazolylidene catalyzed acetoin formation: reaction, tolerance and catalyst recycling. Chem Commun. 2014;50:12308–12310. doi: 10.1039/C4CC04831H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Y, Jiang Y, Li X, Sun B, Teng C, Yang R, Xiong K, Fan G, Wang W. Systematic characterization of the metabolism of acetoin and its derivative ligustrazine in Bacillus subtilis under micro-oxygen conditions. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:3179–3187. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Wei X, Yu W, Wen Z, Chen S. Enhancement of acetoin production from Bacillus licheniformis by 2,3-butanediol conversion strategy: metabolic engineering and fermentation control. Process Biochem. 2017;57:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.03.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang T, Rao Z, Zhang X, Xu M, Xu Z, Yang ST. Metabolic engineering strategies for acetoin and 2,3-butanediol production: advances and prospects. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2017;37:990–1005. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2017.1299680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao YF, Fu J, Tao R, Huang C, Wang ZW, Tang YJ, Chen T, Zhao XM. Systematic metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the industrial-level production of optically pure D-(-)-acetoin. Green Chem. 2017;19:5691–5702. doi: 10.1039/C7GC02753B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drejer EB, Chan DTC, Haupka C, Wendisch VF, Brautaset T, Irla M. Methanol-based acetoin production by genetically engineered: Bacillus methanolicus. Green Chem. 2020;22:788–802. doi: 10.1039/C9GC03950C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Windhorst C, Gescher J. Efficient biochemical production of acetoin from carbon dioxide using Cupriavidus necator H16. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2019;12:163. doi: 10.1186/s13068-019-1512-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao Z, Lv C, Gao C, Qin J, Ma C, Liu Z, Liu P, Li L, Xu P. A novel whole-cell biocatalyst with NAD+ regeneration for production of chiral chemicals. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samuel N, Bao T, Zhang X, Yang T, Xu M, Li X, Komera I, Philibert T, Rao Z. Optimized whole cell biocatalyst from acetoin to 2,3-butanediol through coexpression of acetoin reductase with NADH regeneration systems in engineered Bacillus subtilis. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2017;92:2477–2487. doi: 10.1002/jctb.5267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui Z, Mao Y, Zhao Y, Chen C, Tang Y-J, Chen T, Ma H, Wang Z. Concomitant cell-free biosynthesis of optically pure D-(−)-acetoin and xylitol via a novel NAD+ regeneration in two-enzyme cascade. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2018;93:3444–3451. doi: 10.1002/jctb.5702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui Z, Zhao Y, Mao Y, Shi T, Lu L, Ma H, Wang Z, Chen T. In vitro biosynthesis of optically pure D-(−)-acetoin from meso-2,3-butanediol using 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase and NADH oxidase. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2019;94:2547–2554. doi: 10.1002/jctb.6050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bae SJ, Kim S, Hahn JS. Efficient production of acetoin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by disruption of 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase and expression of NADH oxidase. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27667. doi: 10.1038/srep27667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou X, Zhou X, Zhang H, Cao R, Xu Y. Improving the performance of cell biocatalysis and the productivity of acetoin from 2,3-butanediol using a compressed oxygen supply. Process Biochem. 2018;64:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao C, Zhang L, Xie Y, Hu C, Zhang Y, Li L, Wang Y, Ma C, Xu P. Production of (3S)-acetoin from diacetyl by using stereoselective NADPH-dependent carbonyl reductase and glucose dehydrogenase. Biores Technol. 2013;137:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo Z, Zhao X, He Y, Yang T, Gao H, Li G, Chen F, Sun M, Lee JK, Zhang L. Efficient (3R)-acetoin production from meso-2,3-butanediol using a new whole-cell biocatalyst with co-expression of meso-2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase, NADH oxidase, and Vitreoscilla hemoglobin. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;27:92–100. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1608.08063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D, Zhou J, Chen C, Wei D, Shi J, Jiang B, Liu P, Hao J. R-acetoin accumulation and dissimilation in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;42:1105–1115. doi: 10.1007/s10295-015-1638-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lv X, Dai L, Bai F, Wang Z, Zhang L, Shen Y. Metabolic engineering of Serratia marcescens MG1 for enhanced production of (3R)-acetoin. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2016;3:52. doi: 10.1186/s40643-016-0128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai F, Dai L, Fan J, Truong N, Rao B, Zhang L, Shen Y. Engineered Serratia marcescens for efficient (3R)-acetoin and (2R,3R)-2,3-butanediol production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;42:779–786. doi: 10.1007/s10295-015-1598-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Solem C, Jensen PR. Integrating biocompatible chemistry and manipulating cofactor partitioning in metabolically engineered Lactococcus lactis for fermentative production of (3S)-acetoin. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113:2744–2748. doi: 10.1002/bit.26038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong H, Wang L, Zhao J-Y, Xiao Z. Fermentative production of chiral acetoin by wild-type Bacillus strains. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2019;50:116–122. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2019.1666280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai J, Wang Z, Xiu Z-L. High production of optically pure (3R)-acetoin by a newly isolated marine strain of Bacillus subtilis CGMCC 13141. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2019;42:475–483. doi: 10.1007/s00449-018-2051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker J, Rohles CM, Wittmann C. Metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum for bio-based production of chemicals, fuels, materials, and healthcare products. Metab Eng. 2018;50:122–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deininger P. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. In: Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor,1989. Analytical Biochemistry. 1990, 186:182–183.

- 28.Eggeling L, Bott M. Handbook of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meiswinkel TM, Rittmann D, Lindner SN, Wendisch VF. Crude glycerol-based production of amino acids and putrescine by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biores Technol. 2013;145:254–258. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao Z, Hou X, Lyu X, Xi L, Zhao J-Y. Accelerated green process of tetramethylpyrazine production from glucose and diammonium phosphate. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:106. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-7-106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holtzclaw WD, Chapman LF. Degradative acetolactate synthase of Bacillus subtilis: purification and properties. J Bacteriol. 1975;121:917–922. doi: 10.1128/JB.121.3.917-922.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y-T, Peredelchuk M, Bennett GN, San K-Y. Effect of variation of Klebsiella pneumoniae acetolactate synthase expression on metabolic flux redistribution in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;69:150–159. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(20000720)69:2<150::AID-BIT4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Ooyen J, Noack S, Bott M, Reth A, Eggeling L. Improved l-lysine production with Corynebacterium glutamicum and systemic insight into citrate synthase flux and activity. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:2070–2081. doi: 10.1002/bit.24486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jäger W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Pühler A. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene. 1994;145:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blombach B, Buchholz J, Busche T, Kalinowski J, Takors R. Impact of different CO2/HCO3− levels on metabolism and regulation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol. 2013;168:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters-Wendisch PG, Kreutzer C, Kalinowski J, Patek M, Sahm H, Eikmanns BJ. Pyruvate carboxylase from Corynebacterium glutamicum: characterization, expression and inactivation of the pyc gene. Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 4):915–927. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-4-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwentner A, Feith A, Münch E, Busche T, Rückert C, Kalinowski J, Takors R, Blombach B. Metabolic engineering to guide evolution—creating a novel mode for l-valine production with Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metab Eng. 2018;47:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buchholz J, Schwentner A, Brunnenkan B, Gabris C, Grimm S, Gerstmeir R, Takors R, Eikmanns BJ, Blombach B. Platform engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum with reduced pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity for improved production of l-lysine, l-valine, and 2-ketoisovalerate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:5566. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01741-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blombach B, Schreiner ME, Holatko J, Bartek T, Oldiges M, Eikmanns BJ. L-Valine production with pyruvate dehydrogenase complex-deficient Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:2079–2084. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02826-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma H, Liu H, Zhu N, Chen T. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for acetoin production. Tianjin Daxue Xuebao (Ziran Kexue yu Gongcheng Jishu Ban) J Tianjin Univ Sci Technol. 2014;47:967–972. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radmacher E, Eggeling L. The three tricarboxylate synthase activities of Corynebacterium glutamicum and increase of l-lysine synthesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:587. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milke L, Ferreira P, Kallscheuer N, Braga A, Vogt M, Kappelmann J, Oliveira J, Silva AR, Rocha I, Bott M, et al. Modulation of the central carbon metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum improves malonyl-CoA availability and increases plant polyphenol synthesis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2019;116:1380–1391. doi: 10.1002/bit.26939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogt M, Haas S, Klaffl S, Polen T, Eggeling L, van Ooyen J, Bott M. Pushing product formation to its limit: metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for l-leucine overproduction. Metab Eng. 2014;22:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma Y, Cui Y, Du L, Liu X, Xie X, Chen N. Identification and application of a growth-regulated promoter for improving l-valine production in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb Cell Fact. 2018;17:185. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-1031-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang S, Liu D, Mao Z, Mao Y, Ma H, Chen T, Zhao X, Wang Z. Model-based reconstruction of synthetic promoter library in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biotech Lett. 2018;40:819–827. doi: 10.1007/s10529-018-2539-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petersen S, de Graaf AA, Eggeling L, Mollney M, Wiechert W, Sahm H. In vivo quantification of parallel and bidirectional fluxes in the anaplerosis of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35932–35941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908728199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park SM, Shaw-Reid C, Sinskey AJ, Stephanopoulos G. Elucidation of anaplerotic pathways in Corynebacterium glutamicum via 13C-NMR spectroscopy and GC-MS. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:430–440. doi: 10.1007/s002530050952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang M, Fu J, Zhang X, Chen T. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for enhanced production of acetoin. Biotech Lett. 2012;34:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0730-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tian Y, Fan Y, Liu J, Zhao X, Chen W. Effect of nitrogen, carbon sources and agitation speed on acetoin production of Bacillus subtilis SF4-3. Electron J Biotechnol. 2016;19:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbt.2015.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang TW, Rao ZM, Zhang X, Xu MJ, Xu ZH, Yang ST. Effects of corn steep liquor on production of 2,3-butanediol and acetoin by Bacillus subtilis. Process Biochem. 2013;48:1610–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2013.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luo Q, Wu J, Wu M. Enhanced acetoin production by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens through improved acetoin tolerance. Process Biochem. 2014;49:1223–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2014.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S, Hou Y, Chen X, Liu L. Kick-starting evolution efficiency with an autonomous evolution mutation system. Metab Eng. 2019;54:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jia X, Peng X, Liu Y, Han Y. Conversion of cellulose and hemicellulose of biomass simultaneously to acetoin by thermophilic simultaneous saccharification and fermentation. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:232. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0924-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuan H, Xu Y, Chen Y, Zhan Y, Wei X, Li L, Wang D, He P, Li S, Chen S. Metabolomics analysis reveals global acetoin stress response of Bacillus licheniformis. Metabolomics. 2019;15:25. doi: 10.1007/s11306-019-1492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu N, Xia H, Wang Z, Zhao X, Chen T. Engineering of acetate recycling and citrate synthase to improve aerobic succinate production in Corynebacterium glutamicum. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirchner O, Tauch A. Tools for genetic engineering in the amino acid-producing bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol. 2003;104:287–299. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu Q, Xie L, Li Y, Lin H, Sun S, Guan X, Hu K, Shen Y, Zhang L. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for efficient production of (3R)-acetoin. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2015;90:93–100. doi: 10.1002/jctb.4293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dai J-Y, Cheng L, He Q-F, Xiu Z-L. High acetoin production by a newly isolated marine Bacillus subtilis strain with low requirement of oxygen supply. Process Biochem. 2015;50:1730–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2015.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X, Lv M, Zhang L, Li K, Gao C, Ma C, Xu P. Efficient bioconversion of 2, 3-butanediol into acetoin using gluconobacter oxydans DSM 2003. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6(1):92. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun J-A, Zhang L-Y, Rao B, Shen Y-L, Wei D-Z. Enhanced acetoin production by Serratia marcescens H32 with expression of a water-forming NADH oxidase. Biores Technol. 2012;119:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.05.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jang JW, Jung HM, Im DK, Jung MY, Oh MK. Pathway engineering of Enterobacter aerogenes to improve acetoin production by reducing by-products formation. Enzyme Microbial Technol. 2017;106:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lü C, Ge Y, Cao M, Guo X, Liu P, Gao C, Xu P, Ma C. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus licheniformis for production of acetoin. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:125. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang B, Li X-L, Fu J, Li N, Wang Z, Tang Y-J, Chen T. Production of acetoin through simultaneous utilization of glucose, xylose, and arabinose by engineered Bacillus subtilis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0159298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun J, Zhang L, Rao B, Han Y, Chu J, Zhu J, Shen Y, Wei D. Enhanced acetoin production by Serratia marcescens H32 using statistical optimization and a two-stage agitation speed control strategy. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2012;17:598–605. doi: 10.1007/s12257-011-0587-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fan X, Wu H, Jia Z, Li G, Li Q, Chen N, Xie X. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for the co-production of uridine and acetoin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:8753–8762. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roncal T, Caballero S. Díaz de Guereñu MDM, Rincón I, Prieto-Fernández S, Ochoa-Gómez JR: Efficient production of acetoin by fermentation using the newly isolated mutant strain Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis CML B4. Process Biochem. 2017;58:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu L, Xu QM, Chen T, Cheng JS, Yuan YJ. Artificial consortium that produces riboflavin regulates distribution of acetoin and 2,3-butanediol by Paenibacillus polymyxa CJX518. Eng Life Sci. 2017;17:1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201600239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu H, Jia S, Liu J. Production of acetoin by Bacillus subtilis TH-49. In 2011 International Conference on Consumer Electronics, Communications and Networks (CECNet); 16–18 April 2011. 2011, pp 1524–1527.

- 70.Zhang X, Zhang R, Bao T, Rao Z, Yang T, Xu M, Xu Z, Li H, Yang S. The rebalanced pathway significantly enhances acetoin production by disruption of acetoin reductase gene and moderate-expression of a new water-forming NADH oxidase in Bacillus subtilis. Metab Eng. 2014;23:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang L, Chen S, Xie H, Tian Y, Hu K. Efficient acetoin production by optimization of medium components and oxygen supply control using a newly isolated Paenibacillus polymyxa CS107. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2012;87:1551–1557. doi: 10.1002/jctb.3791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang X, Zhang R, Yang T, Zhang J, Xu M, Li H, Xu Z, Rao Z. Mutation breeding of acetoin high producing Bacillus subtilis blocked in 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;29:1783–1789. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1339-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang L, Liu Q, Ge Y, Li L, Gao C, Xu P, Ma C. Biotechnological production of acetoin, a bio-based platform chemical, from a lignocellulosic resource by metabolically engineered Enterobacter cloacae. Green Chem. 2016;18:1560–1570. doi: 10.1039/C5GC01638J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang Y, Li S, Liu L, Wu J. Acetoin production enhanced by manipulating carbon flux in a newly isolated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Biores Technol. 2013;130:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xiao Z, Gu R, Hou X, Zhao JY, Zhu H, Lu JR. Non-sterilized fermentative production of acetoin with 2,3-butanediol as a main byproduct from maize hydrolysate by a newly isolated thermophilic Bacillus strain. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2017;92:2845–2852. doi: 10.1002/jctb.5301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tao R, Mao YF, Jing FU, Huang C, Wang ZW, Chen T. Effects of inactivation of acetate synthetic pathway genes and overexpression of NADH oxidase on acetoin production in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microbiol China. 2017;44:2530–2538. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1 Primers used in this study. Fig. S1. Growth curves of strains CGS3, CGS4, CGS5, CGS6 and CGR6 in CGXIIY medium (per liter) containing 1 g yeast extract, 5 g (NH4)2SO4, 5 g urea, 1 g KH2PO4, 1 g K2HPO4, 0.25 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g CaCl2, 0.01 g FeSO4·7H2O, 0.1 mg MnSO4·H2O, 1 mg ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.2 mg CuSO4·5H2O, 0.02 mg NiCl·6H2O and 0.4 mg biotin and 40 g glucose, pH 7.0. Fig. S2. Time profiles of the biomass (g/L), glucose, organic acid and acetoin concentrations of strain CGS5 in CGXIIP medium. Fig. S3. (A) The activity of citrate synthase in CGR6 and CGS7. (B) The intracellular pyruvate concentrations of different strains at 12 h. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from three independent cultures. Fig. S4. Measurement of 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine concentrations by GC-FID. A: The 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine standard had a retention time of 10.598 min; B: Batch fermentation products of CGS11 in CGXIIP medium at 24 h; C: Batch fermentation products of CGS11 in CGXIIP medium at 34 h; D: Batch fermentation products of CGS11 in LBRC medium at 29 h; E: Fed-batch fermentation products of CGS11 in LBRC medium at 55 h. Fig. S5. Identification of acetoin enantiomers by GC-FID. A: The optically pure standards of (3R)- and (3S)- had retention times of 9.215 and 9.598 min, respectively; B: Fermentation products of CGS11 in CGXIIP medium; C: Fed-batch fermentation products of CGS11 in LBRC medium at 55 h.