Abstract

Lessons Learned

Radioembolization with yttrium‐90 resin microspheres can be combined safely with full doses of durvalumab and tremelimumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Regional radioembolization with yttrium‐90 resin microspheres did not result in any hepatic or extrahepatic responses to a combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab. The lack of immunomodulatory responses to yttrium‐90 on biopsies before and after treatment rules out a potential role for this strategy in converting a “cold tumor” into an “inflamed,” immune responsive tumor.

Background

PD‐1 inhibitors have been ineffective in microsatellite stable (MSS) metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC). Preclinical models suggest that radiation therapy may sensitize MSS CRC to PD‐1 blockade.

Methods

Patients with MSS metastatic CRC with liver‐predominant disease who progressed following at least one prior line of treatment were treated with yttrium‐90 (Y90) radioembolization to the liver (SIR‐Spheres; Sirtex, Woburn, MA) followed 2–3 weeks later by the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab. A Simon two‐stage design was implemented, with a planned expansion to 18 patients if at least one response was noted in the first nine patients.

Results

Nine patients enrolled in the first stage of the study, all with progressive disease (PD) during or after their first two cycles of treatment. Per preplanned design, the study was closed because of futility. No treatment‐related grade 3 or greater toxicities were recorded. Correlative studies with tumor biopsies showed low levels of tumor‐infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) infiltration in tumor cancer islands before and after Y90 radioembolization.

Conclusion

Y90 radioembolization can be added safely to durvalumab and tremelimumab but did not promote tumor‐directed immune responses against liver‐metastasized MSS CRC.

Discussion

Responses to immunotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer have been largely limited to patients with microsatellite instability. The majority of metastatic colorectal cancers (>95%) are MSS and exhibit resistance to such strategy 1, 2, 3. Combining radiotherapy with PD‐L1 inhibition or CTLA‐4 enhanced antitumor activity synergistically in colorectal cancer tumor models 4, 5. In addition, the combination of both PD‐1 targeting and CTLA‐4 targeting has been associated with more favorable antitumor activity compared with each agent alone in colorectal cancer tumor models 6.

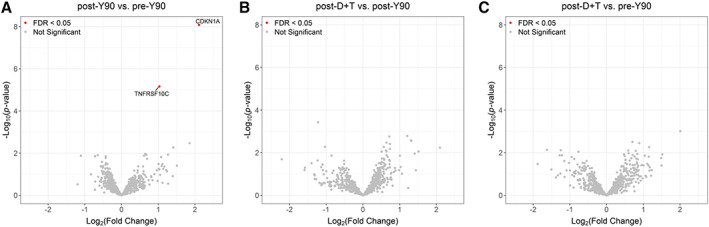

We hypothesized that combining radioembolization with anti–PD‐L1 and anti–CTLA‐4 antibody may boost antitumor response. Contrary to our hypothesis, all patients developed hepatic lesion progression on imaging scan within 8 weeks; six patients also developed extrahepatic disease progression. Three patients developed new lesions while on study treatment. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of liver lesion biopsies showed low levels of TIL infiltration in tumor cancer islands before and after Y90 radioembolization (Fig. 1A). RNA expression analysis by NanoString human immune profiling panel confirmed our IHC results. Other than a transient increase of radiation responsive genes, such as CDKN1A and TNFRSF10C, no other significant immune changes were observed after Y90 radioembolization and after checkpoint blockade with durvalumab and tremelimumab.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of tumor biopsies. (A): Representative image of IHC. (B): Graph depicts the density of CD68+ macrophages in the cancer island. (C): Graph depicts the density of CD68+ macrophages in the stroma area. (D): Graph depicts the density of CD8+ T cells in the stroma area. (E): Graph depicts the density of CD4+ T cells in the stroma area.Abbreviations: D + T, durvalumab and tremelimumab; Y90, yttrium‐90.

In preclinical tumor models, single high‐dose radiation was superior to hyperfractionated doses in terms of generating tumor specific immune response 7, 8, 9. In addition, extended periods of radiation have been shown to diminish antitumor immune responses by eliminating CD8+ T‐cell infiltration 10. Although Y90 is considered high‐dose radiation, its continuous extended radiation may cause the lack of TIL infiltration following radiation in this trial. In addition, limited clinical activity was reported in trials of PD‐1 inhibition in combination with stereotactic body radiation therapy or radiofrequency ablation for patients with metastatic CRC 11, 12. Those results suggest that radiation may have a limited effect in promoting tumor‐directed immune response in MSS CRC.

Overall, the lack of clinical responses in our trial and other trials combining external beam radiation with PD‐1 inhibitors demonstrate the limited benefits of radiation on promoting antitumor immune response in MSS CRC.

Trial Information

| Disease | Colorectal cancer |

| Stage of Disease/Treatment | Metastatic/advanced |

| Prior Therapy | Two prior regimens |

| Type of Study | Phase II, single arm |

| Primary Endpoint | Safety and hepatic response rate |

| Secondary Endpoint | Progression‐free survival, overall survival, overall response rate, abscopal responses, and correlative endpoint |

| Additional Details of Endpoints or Study Design | |

| This study was conducted at City of Hope National Medical Center in the U.S. It was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The study was approved by the local investigation review board and was registered on http://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03005002). | |

| Patient Criteria | |

| This single‐center trial was conducted at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center between June 2017 and June 2018. | |

| Major eligibility criteria included stage IV colorectal cancer with liver‐predominant disease, progression following at least one prior line of treatment, age >18 years, MSS tumor confirmed by polymerase chain reaction or immunohistochemistry, at least one measurable hepatic metastatic disease more than 2 cm in size and readily accessible by ultrasound or computed tomography–guided biopsy; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, identification as a candidate for radioembolization based on liver predominant disease and normal liver function, life expectancy 12 weeks or more, and willingness to undergo serial tumor biopsies. | |

| Major exclusion criteria included prior systemic anticancer immunotherapy such as PD‐1, PD‐L1, or CTLA‐4 inhibitors; receipt of other investigational agents or cytotoxic agents within 4 weeks prior to study treatment; history of prior liver radioembolization; prior documented autoimmune disease within the past 2 years (thyroiditis, vitiligo, or psoriasis not requiring systemic treatment were not excluded), and any unresolved toxicity (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [CTCAE] grade >2) from previous anticancer therapy. | |

| Study Design and Treatment | |

| The study adapted a Simon's minimax design for the efficacy endpoint of response. Given the historic control of 10% response rate with Y90 radioembolization alone, we considered a response rate of 30% to the combination of Y90 radioembolization followed by durvalumab and tremelimumab to be significant. Nine patients were to be enrolled in the safety and efficacy cohort. If no intrahepatic or abscopal responses were noted in the nine patients, the study would close for futility. In the event that at least one response was noted in the first nine patients, the sample size would be expanded to 18 patients. Four or more responses out of the full sample of 18 would be associated with a type I error of 10% and power of 82% for distinguishing a targeted response rate of 30% from a null hypothesis rate of 10%. | |

| Given the low expectations for overlapping toxicities of Y90 resin microspheres radioembolization (SIR‐Spheres) and PD‐L1/CTLA‐4 targeting, we elected to initiate treatment at the full recommended doses of durvalumab plus tremelimumab in the first nine patients 13. If four or more patients of the first nine patients experienced dose‐limiting toxicities (DLTs), the study was to be suspended for enrollment. Interim monitoring of toxicity was performed in the first three, six, and nine patients, respectively. If the DLT rate in the first nine patients was three or fewer, the study was allowed to expand to 18 patients, granted that one or more patients achieved intrahepatic objective response. | |

| Patients who satisfied enrollment criteria received a standard dose of SIR‐Spheres followed 2 weeks later by durvalumab at 1,500 mg intravenous (IV) infusion every 4 weeks (Q4W) for 4 months (up to four doses) and tremelimumab 75 mg IV infusion Q4W for 4 months (up to four doses). After completion of the initial four doses of combination therapy, durvalumab monotherapy was to continue, at the same dose, for 12 months (or until progression). | |

| Dose‐Limiting Toxicity | |

| Grading of DLTs followed the guidelines provided in CTCAE version 4.03. A DLT was defined as any of the following attributable to durvalumab or tremelimumab treatment in the first 8 weeks of treatment: any grade 4 immune‐related adverse event; any grade ≥3 colitis; any grade 3 or 4 noninfectious pneumonitis irrespective of duration; any grade 2 pneumonitis that does not resolve to grade ≤1 within 3 days of the initiation of maximal supportive care; any grade 3 immune‐related adverse event, excluding colitis or pneumonitis, that does not downgrade to grade 2 within 3 days after onset of the event despite optimal medical management including systemic corticosteroids or does not downgrade to grade ≤1 or baseline within 14 days; liver transaminase elevation >8 × upper limit of normal (ULN) or total bilirubin >5 × ULN; inability to receive two cycles because of toxicity. | |

| Evaluation Criteria | |

| Computed tomography scans or magnetic resonance imaging scans of measurable lesions were obtained within 4 weeks before the first dose of durvalumab/ tremelimumab as baseline, then every 8 weeks for study treatment. Response rate was determined using RECIST 1.1 guidelines. Liver metastasis response was considered the primary endpoint of response. Additional response efficacy outcomes included overall response rate (hepatic and extrahepatic) and extrahepatic disease response to investigate possible abscopal effects. Progression‐free survival was reported in all patients and was defined as the time from investigational study treatment (first dose of durvalumab plus tremelimumab) to progression or death. Overall survival was defined as the time from investigation study treatment to death. | |

| Correlative Studies | |

| To investigate the effect of Y90 and durvalumab plus tremelimumab on the tumor microenvironment of hepatic lesions, liver metastatic disease biopsies were obtained at baseline, 1–2 weeks after SIR‐Spheres (and prior to durvalumab plus tremelimumab), and 2–3 weeks after the combination immunotherapy. Biopsies were obtained from the same hepatic lesion to avoid intratumor heterogeneity. For the purpose of evaluating the dynamic alteration of systemic immune response following treatment, peripheral blood samples were obtained within 2 weeks prior to radioembolization, 1–2 weeks following radioembolization, then 4 weeks after the first dose of durvalumab plus tremelimumab. | |

| Multiplex IHC | |

| Multiplex IHC with markers of CD4 (clone SP35, catalog no. 790‐4423, Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ), CD8 (clone SP57, catalog no. 790‐4460, Ventana), CD68 (clone KP‐1, catalog no. 790‐2931, Ventana), and Pan Cytokeratin (clone AE1/AE3/PCK26, catalog no. 760‐2135, Ventana) was used to investigate intratumor immune infiltration following SIR‐Spheres and following durvalumab plus tremelimumab in comparison with baseline. | |

| Each slide was stained on a Ventana Discovery Ultra Autostainer. The formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) slides were deparaffinized in xylene and then rehydrated in decreasing gradations of ethanol. Heat‐induced epitope retrieval was used to allow for better epitope binding. Blocking was performed using Dako Antibody Diluent (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with background reducing for 10 minutes. Marker staining was completed one at a time until all five were done. Primary antibodies were incubated for 1 hour on a shaker at room temperature. Each primary antibody was then detected by Mach 2 Rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) Polymer or Mach 2 Mouse HRP‐Polymer. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin to show nuclear detail. | |

| NanoString | |

| The tumor section was microdissected from patients' unstained FFPE slides and followed by RNA extraction using miRNeasy FFPE kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Then RNA concentration was assessed with the Nanodrop spectrophotometer ND‐1000 and Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). RNA fragmentation and quality control were further determined by 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). RNA expression was then analyzed by NanoString nCounter platform (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA) using with Human PanCancer Immune Profiling panel consisting of 770 genes. All raw data from expression analysis were first aligned with internal positive and negative controls and then normalized to the selected housekeeping genes included in the assay. | |

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Flow Cytometry | |

| Flow cytometry was used to study the alternation of CD4+ T cells (catalog no. 563550, BD, San Diego, CA), CD8+ T cells (catalog no. 612890, BD), Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (catalog no. 561493, BD), CD33+ cells (catalog no. 366616, BioLegend, San Diego, CA), HLA‐DR (catalog no. 307632, BioLegend), CD56+ natural killer (NK) cells (catalog no. 563169, BD), and CD20+ B cells (catalog no. 302322, BioLegend) as well as PD‐1 (catalog no. 329905, BioLegend) in the peripheral blood. | |

| Patient peripheral blood was obtained by venipuncture using heparin collection tubes, transported at room temperature from the clinic to the lab, and processed within 6 hours of drawing. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated via Ficoll‐Paque separation (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) following the manufacturer's instructions. | |

| Single‐cell suspensions were stained at room temperature in 2% fetal bovine serum in phosphate‐buffered saline. For cytokine production assays, cells were stimulated with 50 ng/mL phorbol myristate acetate (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) and 1 μg/mL ionomycin (MilliporeSigma) in the presence of Golgi Plug (BioLegend) for 4 hours. Overnight fixation as needed was performed with intracellular fixation buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Fixation and permeabilization were performed with BD Transcription Factor Buffer (BD Biosciences) or BD Cytofix/Cytoperm buffers as necessary. Samples were acquired using a BD Fortessa with FACS Diva 6.1.3. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using FlowJo version X. | |

| Cytokine assay | |

| A multiplex enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; cytokine 30‐plex human panel, catalog no. LHC6003M, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to detect the alteration of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors in the plasma per manufacturer's instructions using a Bio‐Plex 200 instrument (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA). | |

| Statistical Analysis | |

| The primary endpoint of intrahepatic tumor response and secondary endpoint of overall response were summarized as a hepatic response rate overall response rate, taking the denominator to be all response‐evaluable patients. Exploratory analyses for immune biomarkers were descriptive, using standard statistical summaries (analysis of variance). The differential expression analysis based on Nanostring count data was conducted using edgeR packages in R. An adjusted p value of .05 was applied as the cutoff for determining statistical significance. | |

| Investigator's Analysis | Our data do not support pursuing the combination further in advanced metastatic CRC. |

Drug Information

| Drug 1 | |

| Generic/Working Name | Durvalumab |

| Trade Name | Imfinzi |

| Company Name | AstraZeneca |

| Drug Type | Antibody |

| Drug Class | Immune therapy |

| Dose | 1,500 milligrams (mg) per flat dose |

| Route | IV |

| Schedule of Administration | Q4W |

| Drug 2 | |

| Generic/Working Name | Tremelimumab |

| Company Name | AstraZeneca |

| Drug Type | Antibody |

| Drug Class | Immune therapy |

| Dose | 75 milligrams (mg) per flat dose |

| Route | IV |

| Schedule of Administration | Q4W |

Patient Characteristics

| Number of Patients, Male | 5 |

| Number of Patients, Female | 4 |

| Stage | IV |

| Age | Median: 54 |

| Number of Prior Systemic Therapies | Median: 2 |

| Performance Status: ECOG |

0 — 2 1 — 7 2 — 3 — Unknown — |

| Cancer Types or Histologic Subtypes | CRC, 9 |

Primary Assessment Method

| Title | Study Treatment |

| Number of Patients Screened | 17 |

| Number of Patients Enrolled | 9 |

| Number of Patients Evaluable for Toxicity | 9 |

| Number of Patients Evaluated for Efficacy | 9 |

| Evaluation Method | CTCAE version 4.03 and RECIST 1.1 |

| Response Assessment CR | n = 0 (0%) |

| Response Assessment PR | n = 0 (0%) |

| Response Assessment SD | n = 0 (0%) |

| Response Assessment PD | n = 9 (100%) |

| Outcome Notes | |

| Patient Population | |

| Nine patients with MSS liver‐dominant metastatic colorectal cancer were enrolled and treated from June 2017 to June 2018. Baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. All patients had progressed on all prior standard therapies including a fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan, oxaliplatin, bevacizumab, and an anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (if RAS wild‐type) prior to enrollment on study. Although the disease was liver‐predominant, all patients had evidence of measurable extrahepatic disease, including peritoneum or distant lymph nodes. | |

| Safety and Toxicities | |

| Y90 radioembolization was administrated to all patients safely. On‐study adverse events after durvalumab and tremelimumab administration are listed in Table 2. Treatment with durvalumab and tremelimumab was well tolerated. No treatment‐related grade 3 or greater toxicities were recorded (Table 3). Two patients developed grade 3 alkaline phosphatase increases and grade 4 bilirubin increases due to biliary obstruction caused by disease progression. One patient developed a grade 3 headache due to a right‐sided base‐of‐skull metastasis involving the hypoglossal canal and jugular foramen. Grade 3 small intestinal obstruction due to disease progression was recorded in one case. One patient developed grade 5 myocardial infarction, likely because of severe diffuse coronary artery disease as confirmed by emergency cardiac catheterization and deemed related to uncontrolled preexisting diabetes. We recorded one case of grade 5 death related to brain metastasis in a patient with early progression. | |

| Efficacy | |

| All nine patients were evaluable for response. Six patients received two cycles of immunotherapy with durvalumab and tremelimumab, and three patients received only one cycle because of early progression. As shown in Table 4, all patients developed hepatic lesion progression on imaging scan within 8 weeks; six patients also developed extrahepatic disease progression. Three patients developed new lesions while on study treatment. | |

| Correlative Study of Hepatic Lesion Biopsies | |

| Seven patients had a biopsy at baseline, 2 weeks after Y90, and after immunotherapy. | |

| Multiplex Immunohistochemistry | |

| Multiplex immunohistochemical assay on tumor biopsies showed low levels of (less than 1%) intratumoral CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in all samples among different time points (Fig. 1A). CD68+ macrophages were observed infiltrating cancer islands and stroma, although no statistical significance was found between different time points (Fig. 1B, C). CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells were detected infiltrating the stroma area, but no statistical differences were observed at different time points (Fig. 1D, E). | |

| RNA Expression by NanoString | |

| Among 770 genes analyzed, human immune profiling panel revealed a transient increase of CDKN1A and TNFRSF10C expression after Y90 radioembolization, whereas no significant change in gene expression was recorded following checkpoint blockade with durvalumab and tremelimumab when compared with samples before and after Y90 radioembolization (Fig. 2A–C). | |

| Correlative Study of Peripheral Blood | |

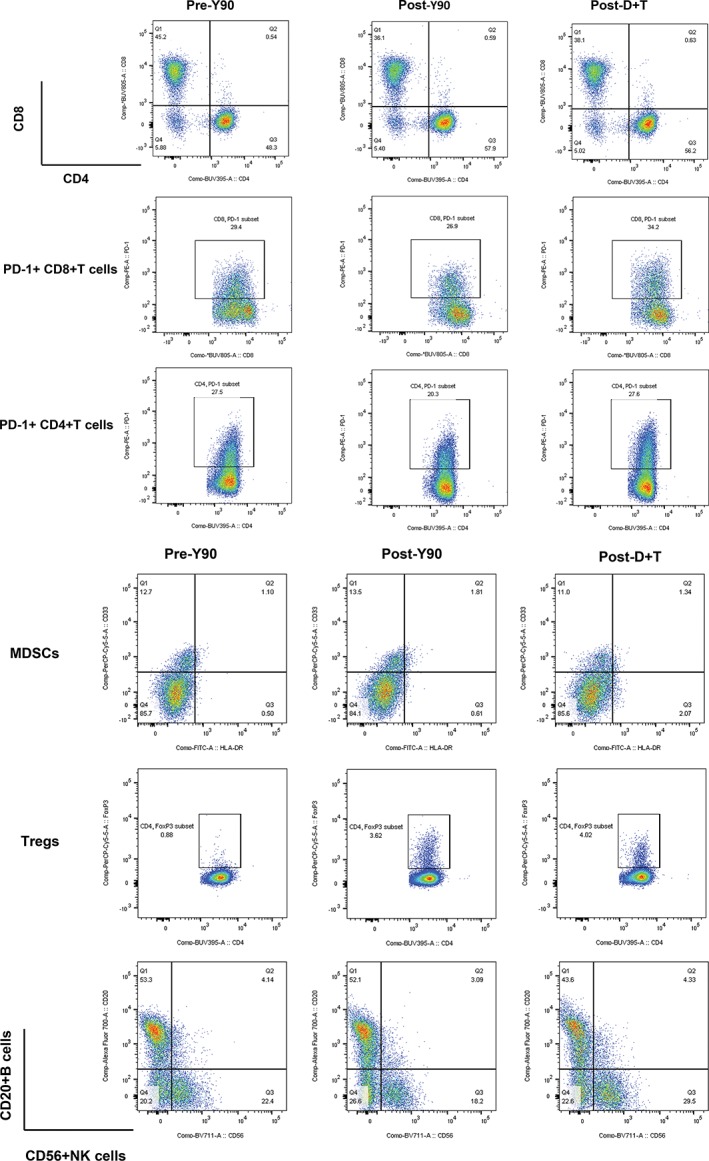

| PBMC analysis by flow cytometry. To capture the effect of Y90 and durvalumab plus tremelimumab on systemic immune response, we analyzed PBMCs at three time points (before Y90 treatment, 2–4 weeks after Y90, and 4 weeks after durvalumab plus tremelimumab). Comparison among three time points showed no significant differences in fractions of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, CD33+ HLA‐DR myeloid‐derived suppressive cells, CD56+ NK cells, CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, PD‐1+ CD8+ T cells, and PD‐1+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3A–H). Representative flow cytometry plots are shown in Figure 4. Additionally, the functionality of peripheral immune cells measured by cytokine expression (IL‐2, IFN‐γ, and TNF‐α) after ex vivo stimulation remained largely unchanged among different time points in CD4+ CD8+ T cells and CD3–CD56+ NK cells (Fig. 5A–F). Representative flow cytometry plots for intracellular cytokine staining are shown in Figure 5G–I. | |

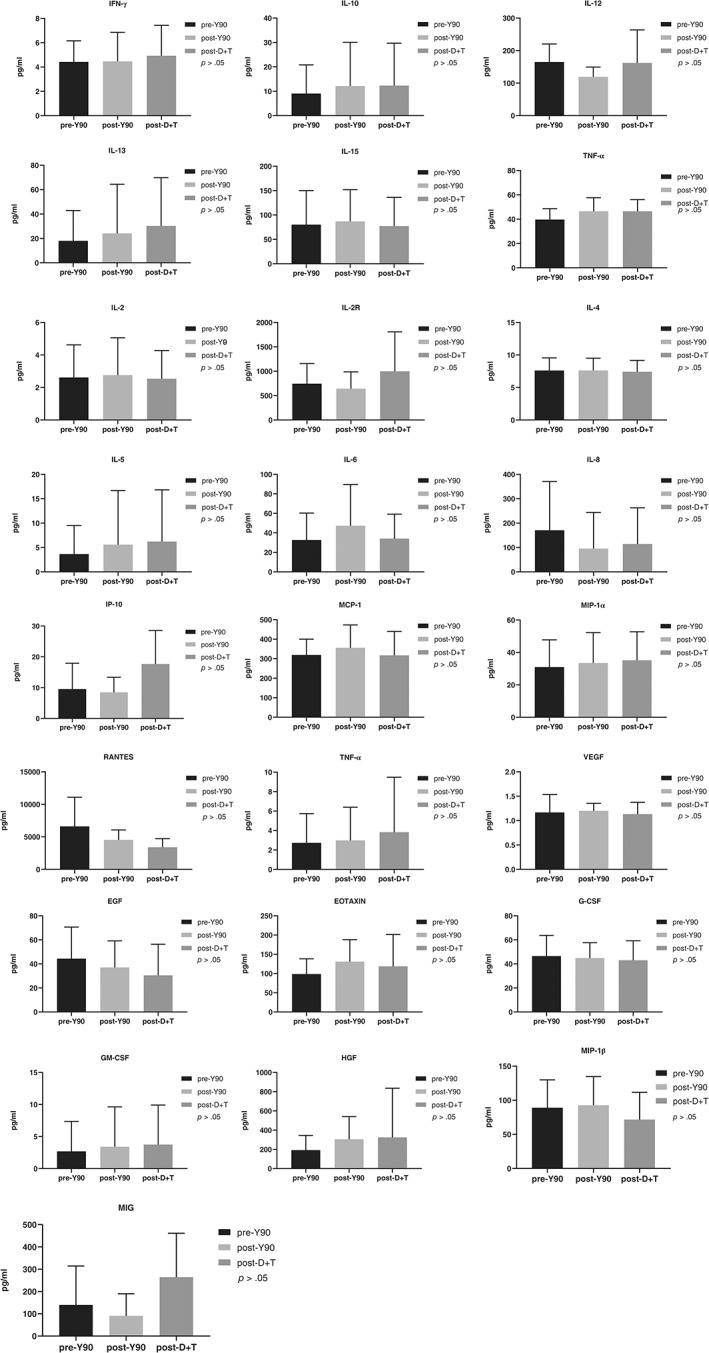

| Cytokines, chemokines, and growth factor analysis by ELISA. Systemic changes in serum signaling molecules were assessed by a 30‐plex ELISA panel to evaluate potential alterations of various cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors following Y90 and durvalumab and tremelimumab treatment. No significant findings were observed between different time points (Fig. 6). | |

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Age, years | Sex | Race | Location of primary tumor | RAS status | BRAF status | ECOG PS | Sites of metastases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | M | White | Left | KARS G12D | Wild type | 1 | Liver and lung |

| 54 | M | White | Left | KRAS G13D | Wild type | 0 | Liver and peritoneum |

| 38 | F | White | Left | Wild type | Wild type | 1 | Liver |

| 62 | M | White | Right | Wild type | BRAF‐V600E | 0 | Liver and RPLN |

| 64 | F | White | Right |

NRAS Q61K KRAS L19F |

BRAF‐G469R | 1 | Liver and RPLN |

| 78 | F | White | Left | Wild type | Wild type | 1 | Liver and pelvis |

| 75 | M | White | Right | NRAS colon 61 | Wild type | 1 | Liver and RPLN |

| 49 | M | NA | Right | KRAS mutation | Wild type | 1 | Liver and lung |

| 53 | F | NA | Left | Wild type | SND1‐BRAF fusion | 1 | Liver and RPLN |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; F, female; M, male; NA, not available; RPLN, retroperitoneal lymph node.

Table 2.

On‐study adverse events (n = 9)

| Adverse event | Cycle 1, n (%) | All cycles, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | |

| Fatigue | 3 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pain | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nausea | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| AST increase | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ALT increase | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ALP increase | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Bilirubin increase | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Headache | 3 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dry skin | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pruritus | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cough | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) |

| Small intestinal obstruction | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Death NOS | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) |

| Dyspnea | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hoarseness | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Anorexia | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Back pain | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Neck pain | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Table 3.

Treatment‐related adverse events (n = 9)

| Adverse event | Cycle 1, n (%) | All cycles, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | |

| Fatigue | 3 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pain | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nausea | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ALP increase | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Headache | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dry skin | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pruritus | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Back pain | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviation: ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Table 4.

Efficacy

| Patient | Cycle of treatment | Site of metastases | Hepatic lesion | Extrahepatic lesion | New lesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Liver and lung | PD | PD | NA |

| 2 | 1 | Liver and peritoneum | PD | Lung metastasis | |

| 3 | 2 | Liver | PD | Skull metastasis | |

| 4 | 2 | Liver and RPLN | PD | PD | NA |

| 5 | 1 | Liver and RPLN | PD | PD | NA |

| 6 | 2 | Liver and pelvis | PD | PD | NA |

| 7 | 2 | Liver and RPLN | PD | PD | Lung metastasis |

| 8 | 1 | Liver and lung | PD | PD | NA |

| 9 | 2 | Liver and RPLN | PD |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; PD, progressive disease; RPLN, retroperitoneal lymph node.

Figure 2.

Volcano plot of statistical significance against fold‐change of NanoString human immune profiling gene signature among different time points. (A): After Y90 versus before Y90. (B): After D + T versus after Y90. (C): After D + T versus before Y90. Abbreviations: D + T, durvalumab and tremelimumab; FDR, false discovery rate; Y90, yttrium‐90.

Figure 3.

Peripheral immune cell alterations before Y90, following Y90 radioembolization, and following durvalumab plus tremelimumab treatment. (A): CD8+ T cells. (B): CD4+ T cells. (C): CD20+ B cells. (D): CD33+ HLA‐DR myeloid‐derived suppressive cells. (E): Regulatory T cells. (F): CD56+ NK cells. (G): CD8+ PD‐1+ T cells. (H): CD4+ PD‐1+ T cells. Abbreviations: D + T, durvalumab and tremelimumab; NK, natural killer; Y90, yttrium‐90.

Figure 4.

Immune cell alteration before Y90, after Y90, and after D + T. Patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative plots show cell population gates for CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, PD‐1+ CD8+ T cells, PD‐1+ CD4+ T cells, MDSCs, regulatory T cells, B cells, and NK cells.

Abbreviations: D + T, durvalumab and tremelimumab; MDSC, myeloid‐derived suppressive cell; NK, natural killer; Treg, regulatory T cell; Y90, yttrium‐90.

Figure 5.

Cytokine production capacity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). PBMCs were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin for 4 hours followed by intracellular staining for IFN‐γ, TNF‐α, and IL‐2 production. Graph depicts the statistical analysis of percentage of immune cells expressing IFN‐γ, TNF‐α, and IL‐2 before Y90, after Y90, and after D + T (A–G). Representative dots of flow cytometry data are shown (H–J).

Abbreviations: D + T, durvalumab and tremelimumab; NK, natural killer; Y90, yttrium‐90.

Figure 6.

Graphs depict the level of various cytokines in the plasma of each patient before Y90, after Y90, and after D + T.

Abbreviations: D + T, durvalumab and tremelimumab; Y90, yttrium‐90.

Assessment, Analysis, and Discussion

| Completion | Study completed |

| Investigator's Assessment | Our data do not support pursuing the combination further in advanced metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC). |

Robust response to checkpoint blockade has been linked to tumor microsatellite instability 14. In contrast, patients with microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors, a phenotype known to associate with lower levels of tumor mutational burden and tumor‐infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) signature, responded poorly 15, 16. Investigation using the combination of durvalumab plus tremelimumab has been conducted recently in a randomized phase II clinical trial with patients with advanced refractory MSS metastatic CRC 17. Minimal activity with <1% response rate and no improvement in progression‐free survival was observed, whereas a moderate improvement in overall survival was noted. Although preclinical models suggested β‐irradiation with yttrium‐90 (Y90) microspheres may induce antitumor immune response and enhance dual checkpoint inhibition for patients with MSS CRC, all nine enrolled patients in this study experienced progressive disease on their first restaging scan. Of note, treatment with durvalumab plus tremelimumab was well tolerated by all patients, as no grade 3 or greater treatment‐related toxicities were recorded. However, such assessment may be confounded by the short treatment duration and short follow‐up because of rapid progression.

Radiation therapy has been shown to induce immunogenic modulation in various tumor types by promoting immunogenic cell death, increasing antigen presentation, facilitating dendritic cell maturation, dampening the function of regulatory T cells, and causing an increase in tumor‐reactive CD8+ T cells 7, 8, 18, 19, 20. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that tumor irradiation is associated with increased CD8+ T‐cell infiltration and decreased myeloid‐derived suppressive cell population within the tumor microenvironment (TME), which ultimately leads to durable remission of colon tumors 10. The combination of radiation, anti–CTLA‐4, and anti–PD‐L1 promotes antitumor response through nonredundant immune mechanisms. Radiation diversifies the intratumor T‐cell receptor repertoire, whereas anti–CTLA‐4 causes peripheral expansion of T‐cell receptor clonotypes and increases the CD8+ T‐cell–to–regulatory T‐cell ratio. PD‐L1 inhibition boosts this antitumor immune response by overcoming T‐cell exhaustion 21. Despite strong evidence of synergy between radiation and checkpoint blockade in the preclinical setting, clinical efficacy of this combination has been limited to highly immunogenic tumors such as melanoma, non‐small cell lung cancer, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma 22, 23, 24, 25. In contrast, limited response was reported in metastatic triple negative breast cancer treated with pembrolizumab plus radiotherapy 26. In addition, preclinical studies have suggested that preexisting TILs are required for stimulating antitumor immunity by radiation therapy and that depletion of CD8+ T cells significantly impaired the efficacy of radiation in tumor control 27, 28. Consistent with concordant observations of immune‐related gene signature in our NanoString assay, immunohistochemistry analysis showed lack of CD8+ T‐cell infiltration in cancer islands of tumor biopsies both before and after Y90 radioembolization, which may help explain the failure of Y90 to augment antitumor activity by durvalumab and tremelimumab.

Preclinical studies have shown that a single high dose of radiation was superior to hyperfractionated doses in terms of generating tumor specific immune response 7, 8, 9. However, contrary to our hypothesis based on such preclinical reports, no increased infiltration of TILs was observed on biopsies following radiation. Indeed, extended period of radiation diminish antitumor immune response by eliminating CD8+ T‐cell infiltration 10. With a half‐life of 2.67 days, Y90 radioembolizaiton delivers 95% of its dose continuously for about 11 days after administration. Although Y90 is considered to be high‐dose radiation, the continuous extended radiation may cause the lack of TIL infiltration following radiation in this trial. Similar results were reported in a pilot study of PD‐1 inhibition in combination with stereotactic body radiation therapy in patients with metastatic CRC to the liver 11. Of the 15 evaluable patients, no objective response was recorded. Similarly, another study also evaluated radiofrequency ablation or external beam radiotherapy in combination with pembrolizumab for patients with metastatic CRC 12. Of the 19 evaluable patients, only one patient was observed with partial response in nonirradiated lesions after radiotherapy. Overall, the limited clinical response reported in these trials was consistent with ours, suggesting that different methods of radiation delivery may not change the effect on mounting antitumor immune response in MSS CRC.

The NanoString assay revealed a transient increase of CDKN1A and TNFRSF10C expression following Y90. As radiation responsive genes, this increase of expression may reflect its reaction to radiotherapy 29. Other results of our correlative study confirmed the limited effects of Y90 on both local and systemic immune response, as no other significant differences were observed at different time points.

We acknowledge that the sample size of this trial was limited and that the timing of biopsy was arbitrary. Our results nonetheless demonstrated the limited effects of radiation on the TME of MSS CRC. The design of this trial and many others was largely based on the results of preclinical mouse models, such as MC38 and CT26. These models may not properly represent the immune contexture of MSS colorectal cancer, as they are highly immunogenic in general 30, 31. The lack of clinical responses in our trial, along with others with a similar setting, recommends caution in the use of combination radiation and checkpoint blockade in future trials and calls for better preclinical models to mimic the TME of MSS CRC.

Disclosures

John Park: Sirtex (C/A); Joseph Chao: AstraZeneca (C/A); Marwan Fakih: Amgen, Array, Bayer (C/A), AstraZeneca, Amgen, Novartis (RF), Amgen (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Figures and Tables

Acknowledgments

This trial was supported by AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, AWD‐P060061. The correlative study was supported by City of Hope institutional funding. Research reported in this publication included work performed in the Analytical Cytometry Core, Analytical Pharmocology Core, and Pathology Core supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P30CA033572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

Footnotes

- Sponsor: AstraZeneca

- Principal Investigator: Marwan Fakih

- IRB Approved: Yes

References

- 1. Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair‐deficient or microsatellite instability‐high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): An open‐label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1182–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KYM et al. Durable clinical benefit with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in DNA mismatch repair‐deficient/microsatellite instability‐high metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Neil BH, Wallmark JM, Lorente D et al. Safety and antitumor activity of the anti‐PD‐1 antibody pembrolizumab in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma. PLoS One 2017;12:e0189848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B et al. Irradiation and anti–PD‐L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest 2014;124:687–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N et al. Fractionated but not single‐dose radiotherapy induces an immune‐mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti–CTLA‐4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:5379–5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zippelius A, Schreiner J, Herzig P et al. Induced Pd‐L1 expression mediates acquired resistance to agonistic anti‐CD40 treatment. Cancer Immunol Res 2015;3:236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schaue D, Ratikan JA, Iwamoto KS et al. Maximizing tumor immunity with fractionated radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;83:1306–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y et al. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: Changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood 2009;114:589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lugade AA, Moran JP, Gerber SA et al. Local radiation therapy of B16 melanoma tumors increases the generation of tumor antigen‐specific effector cells that traffic to the tumor. J Immunol 2005;174:7516–7523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Filatenkov A, Baker J, Mueller AM et al. Ablative tumor radiation can change the tumor immune cell microenvironment to induce durable complete remissions. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:3727–3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duffy AG, Makarova‐Rusher OV, Pratt D et al. A pilot study of AMP‐224, a PD‐L2 Fc fusion protein, in combination with stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(suppl 4):560A. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Segal NH, Kemeny NE, Cercek A et al. Non‐randomized phase II study to assess the efficacy of pembrolizumab (Pem) plus radiotherapy (RT) or ablation in mismatch repair proficient (pMMR) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(suppl 15):3539A. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peters S, Antonia S, Goldberg SB et al. 191TiP: MYSTIC: A global, phase 3 study of durvalumab (MEDI4736) plus tremelimumab combination therapy or durvalumab monotherapy versus platinum‐based chemotherapy (CT) in the first‐line treatment of patients (pts) with advanced stage IV NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11(suppl 4):S139–S140. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cristescu R, Mogg R, Ayers M et al. Pan‐tumor genomic biomarkers for Pd‐1 checkpoint blockade–based immunotherapy. Science 2018;362:eaar3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Llosa NJ, Cruise M, Tam A et al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter‐inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer Discov 2015;5:43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H et al. PD‐1 blockade in tumors with mismatch‐repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2509–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen EX, Jonker DJ, Kennecke HF et al. CCTG CO.26 trial: A phase II randomized study of durvalumab (D) plus tremelimumab (T) and best supportive care (BSC) versus BSC alone in patients (pts) with advanced refractory colorectal carcinoma (rCRC). J Clin Oncol 2019;37(suppl 4):481A. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Golden EB, Pellicciotta I, Demaria S et al. The convergence of radiation and immunogenic cell death signaling pathways. Front Oncol 2012;2:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2006;203:1259–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cao M, Cabrera R, Xu Y et al. Gamma irradiation alters the phenotype and function of CD4 + CD25+ regulatory T cells. Cell Biol Int 2009;33:565–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Twyman‐Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non‐redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature 2015;520:373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hiniker SM, Reddy SA, Maecker HT et al. A prospective clinical trial combining radiation therapy with systemic immunotherapy in metastatic melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016;96:578–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1919–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Theelen W, Peulen H, Lalezari F et al. Randomized phase II study of pembrolizumab after stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) versus pembrolizumab alone in patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer: The PEMBRO‐RT study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(suppl 15):9023A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wise‐Draper TM, Old MO, Worden FP et al. Phase II multi‐site investigation of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab and adjuvant concurrent radiation and pembrolizumab with or without cisplatin in resected head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(suppl 15):6017A. [Google Scholar]

- 26. McArthur HL, Barker CA, Gucalp A et al. A single‐arm, phase II study assessing the efficacy of pembrolizumab (pembro) plus radiotherapy (RT) in metastatic triple negative breast cancer (mTNBC). J Clin Oncol 2018;36(suppl 5):14A.29035645 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dovedi SJ, Cheadle EJ, Popple AL et al. Fractionated radiation therapy stimulates antitumor immunity mediated by both resident and infiltrating polyclonal T‐cell populations when combined with PD‐1 blockade. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:5514–5526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gough MJ, Crittenden MR, Sarff M et al. Adjuvant therapy with agonistic antibodies to CD134 (OX40) increases local control after surgical or radiation therapy of cancer in mice. J Immunother 2010;33:798–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Badie C, Dziwura S, Raffy C et al. Aberrant CDKN1A transcriptional response associates with abnormal sensitivity to radiation treatment. Br J Cancer 2008;98:1845–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lechner MG, Karimi SS, Barry‐Holson K et al. Immunogenicity of murine solid tumor models as a defining feature of in vivo behavior and response to immunotherapy. J Immunother 2013;36:477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Juneja VR, McGuire KA, Manguso RT et al. PD‐L1 on tumor cells is sufficient for immune evasion in immunogenic tumors and inhibits CD8 T cell cytotoxicity. J Exp Med 2017;214:895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]