Abstract

Next-generation sequencing of Sri Lankan families with inherited cancer syndromes resulted in the identification of five BRCA2 variants of unknown clinical significance. Interpreting such variants poses significant challenges for both clinicians and patients. Using a mouse embryonic stem cell-based functional assay, we found I785V, N830D, and K2077N to be functionally indistinguishable from wild-type BRCA2. Specific but mild sensitivity to olaparib and reduction in homologous recombination (HR) efficiency suggest partial loss of function of the A262T variant. This variant is located in the N-terminal DNA binding domain of BRCA2 that can facilitate HR by binding to dsDNA/ssDNA junctions. P3039P is clearly pathogenic because of premature protein truncation caused by exon 23 skipping. These findings highlight the value of mouse embryonic stem cell-based assays for determining the functional significance of variants of unknown clinical significance and provide valuable information regarding risk estimation and genetic counseling of families carrying these BRCA2 variants.

Keywords: BRCA2, Classification, Functional assay, Inherited cancer, Next-generation sequencing, Variants of unknown clinical significance (VUS)

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women and a leading cause of cancer morbidity and mortality in Sri Lanka [1]. Latest epidemiological reports indicate that breast cancer accounts for 13.1% of all cancers and 24% of all female cancers in the country [2]. These figures highlight the importance of identifying individuals at risk of breast cancer early so that appropriate management and preventive measures could be undertaken to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with this disease. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based genomic testing has facilitated rapid, precise genetic diagnosis and management of patients with inherited cancer syndromes.

In 2015, using the Illumina MiSeq NGS platform and an in-house developed validated bioinformatics pipeline, multi-gene cancer panel testing and clinical exome sequencing were successfully implemented at our center for the genetic evaluation of patients with inherited cancer syndromes [3, 4]. However, the implementation of NGS-based genomic testing into our routine clinical cancer practice has simultaneously yielded a multitude of rare germline variants in cancer predisposing genes that are known as variants of unknown clinical significance (VUS). This poses significant challenges for both patients and clinicians, especially with regard to risk assessment, genetic counseling, and clinical decision making. Such variants might not contribute to risk assessment and may at times prompt anxiety and overtreatment. In this regard, the non-representation of genetic variants found in the Sri Lankan population in public databases is an additional drawback and challenge. To overcome this limitation, often times we resort to careful assessment of the three-generation pedigrees and testing the particular variant in other affected and unaffected family members, for further confirmation and to identify a clear pattern of co-segregation in the family members. However, the only means to precisely delineate the exact biological significance of these variants is through functional studies. This study aims to describe the functional assays which were conducted to determine the functional significance of five VUS identified in Sri Lankan families with inherited cancer syndromes.

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical and genetic test data of consecutive patients from families with two or more patients with inherited cancer syndromes who underwent NGS-based testing between January 2015 and December 2018 which were maintained prospectively in a database. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo [EC-13-182]. Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. The genetic variants were classified using the five-class system as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, VUS, likely benign, or benign according to the lab classification criteria. This criteria relies on the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association of Molecular Pathology [5]. All retained variants underwent thorough assessment and review of available evidence (e.g., population frequency databases, published literature, case/control and functional studies, internal co-occurrence and co-segregation data, evolutionary conservation, and in silico functional predictions) to arrive at a final variant classification. The variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes identified in this cohort are summarized in Table 1. We focused our studies on five VUS identified in the BRCA2 gene in this cohort for further investigations to determine their functional significance using a mouse embryonic stem (mES) cell-based assay.

Table 1.

Summary of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants identified in Sri Lankan families with inherited cancer syndromes

| Variant | Amino acid change | ClinVar interpretation | Cancer types in index cases | Cancer types in family members |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1:c.1575del | p.Gln526Lysfs | Pathogenic | Breast | Breast, ovarian, endometrial |

| BRCA1:c.3392A>G | p.Asp1131Gly | VUS | Breast | Breast |

| BRCA1:c.4120_4121delAG | p.Ser1374Terfs | Pathogenic | Breast | Breast, thyroid |

| BRCA1:c.5289delG | p.Leu1764Terfs | Pathogenic | Breast, ovary | Breast, endometrial, ovarian, thyroid, hepatic, esophageal |

| BRCA1:c.68_69delAG | p.Glu23Valfs | Pathogenic | Ovary | Breast |

| BRCA1:c.1881_1884del | p.Ser628fs | Pathogenic | Breast | Breast, colorectal |

| BRCA2:c.784G>A | p.Ala262Thr | VUS | Breast and ovarian | Breast, thyroid, and endometrial |

| BRCA2:c.2353A>G | p.Ile785Val | VUS | Prostate | Colorectal and thyroid |

| BRCA2:c.2488A>G | p.Asn830Asp | VUS | Breast | Ovarian |

| BRCA2:c. 6231G>C | p.Lys2077Asn | Likely Benign/VUS | Breast | Breast |

| BRCA2:c.9117G>A | p.Pro3039= | Pathogenic | Breast | Breast, thyroid, and endometrial |

| BRCA2:c.5727_5728insG | p.Asn1910fs | Pathogenic | Ovary | Ovarian, liver, colon, prostate |

| BRCA2:c.1296_1297delGA | p.Asn433Glnfs | Pathogenic | Breast, fallopian tube | Breast, liver, endometrial, colorectal, ovarian, esophageal |

| BRCA2:c.5576_5579delTTAA | p.Ile1859Lysfs | Pathogenic | Breast | Breast, endometrial, gastric |

| BRCA2:c.5621_5624delTTAA | p.Ile1874Argfs | Pathogenic | Breast | Breast, ovarian |

Mouse embryonic stem (mES) cell-based assays provide a simple and reliable assay to test the functional significance of BRCA2 VUS [6]. The assay is based on the observation that BRCA2 is essential for mES cell viability. The ability of human BRCA2 to rescue the lethality of Brca2-deficient mES cells and the sensitivity of viable cells to various DNA damaging agents are used to evaluate the functional significance of the variants [6]. We used this approach to determine the functional significance of five unclassified BRCA2 germline variants [NM_000059.3:c.784G>A|NP_000050.2:p.Ala262Thr|rs397507393; NM_000059.3:c.2353A>G|NP_000050.2:p.Ile785Val|rs747748537; NM_000059.3:c.2488A>G|NP_000050.2:p.Asn830Asp|rs574039421; NM_000059.3:c.6231G>C|NP_000050.2:p.Lys2077Asn|rs541826447;

NM_000059.3:c.9117G>A|NP_000050.2:p.Pro3039Pro|rs28897756] identified in Sri Lankan families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

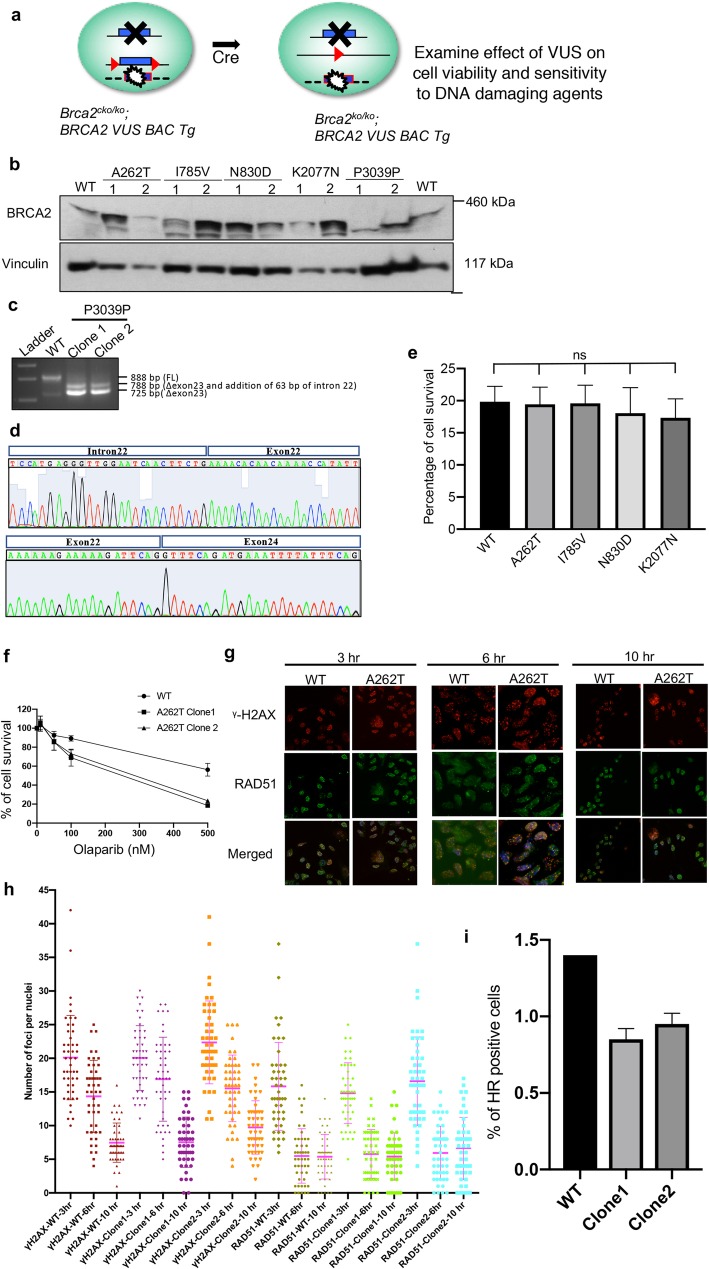

Functional analysis of BRCA2 variants in Brca2cko/ko mES cells.a Schematic representation of the mES cell-based functional assay. b Expression of BRCA2 variants in mES cells by Western blotting. Two independent clones were generated for each variant. Vinculin was used as loading control. c Expression of BRCA2 P3039P by RT-PCR using primers from exons 20 (5′-AGGAAGAAAAGGAAGCAGCAAAATATGTGG-3′) and 25 (5′-TCTCCAGCAAATAAAGTAAGAAGG-3′) revealed lack of full-length transcript. Two alternatively spliced transcripts were observed. d Sequence analysis of the two transcripts revealed major alternatively spliced transcript skipped exon 23 (lower band) and a minor form that skipped exon 23 but retained 63pb of intron 22 (upper band). e Quantification of viability of Brca2ko/ko mES cell by various BRCA2 variants. Two independent BAC clones expressing the variants were analyzed. Average numbers of viable cells from two independent clones were plotted. mES cell clone expressing WT BRCA2 was used as control. f Clonogenic survival assay confirming sensitivity of mES cells expressing A262T to olaparib (P value < 0.001 at 100 nM and < 0.0001 at 500 nM concentrations using a multiple t-test). g Representative images showing γH2AX and RAD51 foci at 3, 6, and 10 h post 10 Gy IR in mES cells expressing WT and A262T BRCA2. h Quantification of γH2AX and RAD51 foci at 3, 6, and 10 h post 10 Gy IR in mES cells expressing WT and A262T BRCA2. i Quantification of homologous recombination using a GFP-based HR reporter in mES cells expressing WT and A262T BRCA2 (P values are 0.008 for Clone 1 and 0.01 for Clone 2 using paired t-test)

The desired BRCA2 variants were generated in bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC) and expressed in mES cells (Fig. 1b). We failed to detect the full-length protein expression of BRCA2 p.Pro3039Pro variant by Western analysis. This silent mutation at the coding level resulted in skipping of exon 23 and production of a smaller non-functional protein (Fig. 1c, d). This variant is known to disrupt a splice donor site and has previously been shown in in vitro studies to cause aberrant mRNA processing with skipping of exon 23 [7]. Our finding further corroborates the earlier observations and clearly establishes the pathogenicity of this variant. p.Pro3039Pro has previously been reported in families with breast and/or ovarian cancer [8–12].

The p.Ile785Val, p.Asn830Asp, and p.Lys2077Asn variants are likely to be neutral as they rescued mES cell lethality and were indistinguishable from wild-type (WT) BRCA2 in their sensitivity to DNA damaging agents such as cisplatin, camptothecin, mitomycin C, methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), olaparib (poly ADP-ribose polymerase inhibitor), and γ-irradiation (IR) as measured by XTT cell-proliferation assay (Fig. 1e, Table 2). Interestingly p.Ala262Thr was also indistinguishable from WT in all assays except it exhibited specific but mild sensitivity to olaparib among the drugs tested. This was further confirmed by clonogenic survival assay (Fig. 1f). We did not observe any defect in RAD51 recruitment at 3, 6, and 10 h after 10 Gy IR (Fig. 1g, h). However, using a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-based reporter assay [13], we observed a reduction in homologous recombination (HR) efficiency of p.Ala262Thr compared to WT BRCA2 (Fig. 1i) suggesting that RAD51 foci formation may not be sensitive enough to detect minor reduction in HR efficiency.

Table 2.

Sensitivity of mES cells expressing BRCA2 variants to different DNA-damaging agents

| Variants | MMS | Mitomycin C | Cisplatin | Camptothecin | Olaparib | IR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A262T | No | No | No | No | Yes (mild) | No |

| I785V | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| N830D | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| K2077N | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| P3039P | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA not available, mES mouse embryonic stem cells, MMS methyl methanesulfonate, IR γ-irradiation

These findings highlight the value of mES cell-based assays for determining the functional significance of unclassified variants and further extends the spectrum of germline pathogenic variants in the BRCA2 gene with functional evidence. Our findings revealed a mild and specific effect of p.Ala262Thr variant on sensitivity to olaparib as well as impact on HR. To date, most pathogenic mutations in BRCA2 have been identified in the C-terminal DNA binding domain of BRCA2 [14, 15]. A second DNA binding domain has been identified near the N-terminus of BRCA2 between residues 250 and 500, which contains a putative zinc-finger (zf) PARP-like domain between residues 265 and 349 [16]. DNA binding studies have shown its ability to bind to various DNA structures including ssDNA. Interestingly, unlike the C-terminal domain, it also exhibits dsDNA binding activity, which is predicted to facilitate the interaction of BRCA2 to dsDNA/ssDNA junctions during HR. Our preliminary studies with p.Ala262Thr variant did not reveal a defect in binding of BRCA2 to the chromatin (data not shown). Future studies will be aimed at understanding if p.Ala262Thr has any effect on RPA-dependent strand exchange ability of RAD51. A defect in RPA-dependent strand exchange will explain the specific effect of this variant on HR and olaparib sensitivity [16].

Acknowledgements

The research was sponsored by the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- BAC

Bacterial artificial chromosomes

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- HR

Homologous recombination

- IR

γ-irradiation

- mES

Mouse embryonic stem

- MMS

Methyl methanesulfonate

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- VUS

Variants of unknown clinical significance

- WT

Wild-type

Authors’ contributions

NDS, KB, and SKS drafted the manuscript. KB, TS, SS, LC, and ES conducted the laboratory assays. VHWD critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written, informed consent from all study participants and ethical clearance to conduct this study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo [EC-13-182].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nirmala Sirisena and Kajal Biswas contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Nirmala Sirisena, Email: nirmala@anat.cmb.ac.lk.

Kajal Biswas, Email: kajal.biswas2@nih.gov.

Teresa Sullivan, Email: sullivti@mail.nih.gov.

Stacey Stauffer, Email: stauffer@nih.gov.

Linda Cleveland, Email: clevelal@mail.nih.gov.

Eileen Southon, Email: eileen.southon2@nih.gov.

Vajira H. W. Dissanayake, Email: vajira@anat.cmb.ac.lk

Shyam K. Sharan, Email: sharans@mail.nih.gov

References

- 1.National Cancer Control Programme . Cancer incidence data. National Cancer Control Programme: Sri Lanka; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.GLOBOCAN . GLOBOCAN 2018: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirisena ND, Neththikumara N, Wetthasinghe K, Dissanayake VH. Implementation of genomic medicine in Sri Lanka: initial experience and challenges. Appl Transl Genom. 2016;9:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.atg.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirisena ND, Dissanayake VHW. Genetics and genomic medicine in Sri Lanka. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7:e744. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, Kalia SS, Korf BR, Martin CL, et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:565–574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuznetsov SG, Liu P, Sharan SK. Mouse embryonic stem cell-based functional assay to evaluate mutations in BRCA2. Nat Med. 2008;14:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nm.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonatti F, Pepe C, Tancredi M, Lombardi G, Aretini P, Sensi E, et al. RNA-based analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene alterations. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;170:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peelen T, van Vliet M, Bosch A, Bignell G, Vasen HF, Klijn JG, et al. Screening for BRCA2 mutations in 81 Dutch breast-ovarian cancer families. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:151–156. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novakovic S, Milatovic M, Cerkovnik P, Stegel V, Krajc M, Hocevar M, et al. Novel BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic mutations in Slovene hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:1619–1627. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, Rosen B, Bradley L, Fan I, et al. Population BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: a kin-cohort study in Ontario, Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1694–1706. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombo M, De Vecchi G, Caleca L, Foglia C, Ripamonti CB, Ficarazzi F, et al. Comparative in vitro and in silico analyses of variants in splicing regions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes and characterization of novel pathogenic mutations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acedo A, Sanz DJ, Duran M, Infante M, Perez-Cabornero L, Miner C, et al. Comprehensive splicing functional analysis of DNA variants of the BRCA2 gene by hybrid minigenes. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R87. doi: 10.1186/bcr3202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierce AJ, Johnson RD, Thompson LH, Jasin M. XRCC3 promotes homology-directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2633–2638. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biswas K, Das R, Eggington JM, Qiao H, North SL, Stauffer S, et al. Functional evaluation of BRCA2 variants mapping to the PALB2-binding and C-terminal DNA-binding domains using a mouse ES cell-based assay. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3993–4006. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guidugli L, Shimelis H, Masica DL, Pankratz VS, Lipton GB, Singh N, et al. Assessment of the clinical relevance of BRCA2 missense variants by functional and computational approaches. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Nicolai C, Ehlen A, Martin C, Zhang X, Carreira A. A second DNA binding site in human BRCA2 promotes homologous recombination. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12813. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.