Abstract

Despite the therapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in ischemic diseases, pathophysiological conditions, including hypoxia, limited nutrient availability, and oxidative stress restrict their potential. To address this issue, we investigated the effect of melatonin on the bioactivities of MSCs. Treatment of MSCs with melatonin increased the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α). Melatonin treatment enhanced mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in MSCs in a PGC-1α-dependent manner. Melatonin-mediated PGC-1α expression enhanced the proliferative potential of MSCs through regulation of cell cycle-associated protein activity. In addition, melatonin promoted the angiogenic ability of MSCs, including migration and invasion abilities and secretion of angiogenic cytokines by increasing PGC-1α expression. In a murine hindlimb ischemia model, the survival of transplanted melatonin-treated MSCs was significantly increased in the ischemic tissues, resulting in improvement of functional recovery, such as blood perfusion, limb salvage, neovascularization, and protection against necrosis and fibrosis. These findings indicate that the therapeutic effect of melatonin-treated MSCs in ischemic diseases is mediated via regulation of PGC-1α level. This study suggests that melatonin-induced PGC-1α might serve as a novel target for MSC-based therapy of ischemic diseases, and melatonin-treated MSCs could be used as an effective cell-based therapeutic option for patients with ischemic diseases.

Keywords: Melatonin, Mesenchymal stem cells, PGC-1α, Hindlimb ischemia, Cell-based therapy

INTRODUCTION

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are one of the most effective candidates for stem cell-based therapies for ischemic diseases (Lv et al., 2014). They can be isolated from a wide range of tissues, including the bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical blood, and peripheral blood, which represent the major sources of MSCs for stem cell-based therapeutics (Chamberlain et al., 2007). In addition, since they exhibit self-renewal and multipotent capacities, many researchers have focused on the development of functional MSCs for regenerative medicine (Chamberlain et al., 2007; Lv et al., 2014). In preclinical animal models and clinical trials, autologous and allogeneic MSCs have shown potential therapeutic benefits in several clinical disorders, such as stroke, acute myocardial infarction, spinal cord injury, acute kidney failure, liver fibrosis, and wound healing (Caplan and Correa, 2011). They have also been shown to exhibit therapeutic activities, including immunomodulation, secretion of angiogenic cytokines and mitogens, tissue regeneration, and antimicrobial effect (Caplan and Correa, 2011). However, under pathophysiological conditions, such as ischemia, restricted nutrient availability, oxidative stress, and inflammation, apoptosis, and cell death of the transplanted MSCs occur, thereby inhibiting the therapeutic effects of MSCs. Furthermore, the therapeutic effects of autologous MSCs isolated from patients with chronic diseases are suppressed by the pathological environment in patients. Therefore, it is important to enhance the bioactivities of MSCs for protecting them against pathophysiological conditions in injured tissues.

Melatonin, N-acetyl-5-methoxytriptamine, is an endogenous pineal hormone produced by the pineal gland as well as several other tissues, including the bone marrow, gut, and liver (Reiter, 1991; Garcia et al., 2014). Previous researches have described that melatonin mainly regulates sleep, circadian rhythms, neuroendocrine actions, and immune defense (Reiter, 1991; Jan et al., 2009; Reiter et al., 2009). Furthermore, it has various biological roles, such as anti-apoptotic, autophagy-modulating, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and anti-oxidant effects (Mauriz et al., 2013; Fernandez et al., 2015; Reiter et al., 2016; Su et al., 2017). In MSC biology, accumulating evidences have indicated that MSCs treated with melatonin show enhanced therapeutic efficacy in various ischemic diseases, including myocardial infarction, hindlimb ischemia, and acute lung-ischemia-reperfusion injury (Yip et al., 2013; Han et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017). Although the therapeutic effect of melatonin on MSCs in several ischemic diseases is evident, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α) is a central transcription coactivator that is involved in various biological responses, such as mitochondrial biogenesis, energy metabolism, thermogenesis, and reduction of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Zhou et al., 2011). PGC-1α is also a powerful anti-aging molecule because it regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and inhibits generation of cellular ROS by upregulating the expression of anti-oxidant enzymes (Li et al., 2008). Deletion of PGC-1α in skeletal stem cells induces dysfunction of bone formation, suggesting that PGC-1α controls skeletal aging (Yu et al., 2018). Moreover, PGC-1α has been shown to have a therapeutic effect on angiogenesis in hindlimb ischemia. Survival of transplanted cells in the injured tissues of hindlimb ischemia was increased in MSCs transfected with PGC-1α compared with controls, leading to improvement of blood flow perfusion and angiogenesis (Arany et al., 2008). These findings indicate that regulation of PGC-1α level in MSCs could be a novel approach for developing MSC-based therapeutics. In this study, we investigated whether melatonin increases the bioactivities of MSCs, and whether melatonin-treated MSCs enhance the functional recovery of ischemic tissues in hindlimb ischemia. Further, we reported that melatonin is involved in mitochondrial energy metabolism, cell expansion, migration, invasion, and secretion of angiogenic cytokines through upregulation of PGC-1α expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Human adipose-derived MSCs were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The supplier certified that the human MSCs expressed the cell surface markers CD73 and CD105, but not CD31, and could undergo adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation when cultured in specific differentiation media. Cells were grown in minimum essential medium alpha (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 U/mL penicillin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Western blot analysis

Total cellular proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell lysates were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk and incubated with primary antibodies against PGC-1α (Novus Biological, Centennial, CO, USA), cyclin E (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CDK4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and α-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After incubation of membranes with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a dark room.

Inhibition of PGC-1α expression by small-interference RNA

MSCs were seeded in 60 mm dishes and transfected with small-interference RNA (siRNA) in serum-free Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The siRNA used to block PGC-1α (The PGC-1α siRNA no. 1 sequence: 5ʹ-UCACCGAGACCGACGUUAA-3ʹ, no. 2 sequence: 5ʹ-GAUCGAGCAUGGUCCUCUU-3ʹ, no. 3 sequence: 5ʹ-AGAUGUGUAUCACCCAGUA-3ʹ, and no. 4 sequence: 5ʹ-GACCGUUACUAUCGUGAAA-3ʹ) and a scrambled sequence (scrambled siRNA no. 1 sequence: 5ʹ-UGGU UUACAUGUCGACUAA-3ʹ, no. 2 sequence: 5ʹ-UGGUUUAC AUGUUGUGUGA-3ʹ, no. 3 sequence: 5ʹ-UGGUUUACAUGU UUUCUGA-3ʹ, and no. 4 sequence: 5ʹ-UGGUUUACAUGUU UUCCUA-3ʹ) were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA).

Mitochondrial complex I and IV activity

Mitochondrial fractions isolated from MSCs were incubated for 3 min in an assay medium (250 mmol/L sucrose, 50 mmol/L potassium phosphate, 1 mmol/L potassium cyanide, 50 μmol/L decylubiquinone, and 0.8 μmol/L antimycin, pH 7.4). Complex I activity was assessed from the rate of oxidation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH; 100 mm) at 340 nM. Complex IV activity was analyzed by adding 75 mL of cytochrome c previously reduced with sodium borohydride and measuring the absorbance at 550 nm.

Measurement of mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR)

Mitochondrial OCR was measured using Extracellular O2 Consumption Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Briefly, cells were plated on 96-well cell culture plates and incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C overnight. The culture medium was removed and replaced with 150 μL of fresh culture medium and incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 30 min. Extracellular O2 consumption reagent (10 μL) and two drops of pre-warmed high sensitivity mineral oil were added to each well, and the absorbance was measured using a multidetection microplate reader (Perkin Elmer, Billerica, MA, USA) at 37°C for 80 min at 2-minute intervals at wavelengths of 340 and 650 nm.

Single cell expansion assay

MSCs were dissociated into a single cell suspension using trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cell density was adjusted to 1 cell per 100 μL via a limited-dilution assay. Single cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 for 10 days.

Migration assay

The migration capacity of MSCs was assessed by scratched wound healing scratch assay. MSCs were plated on 6-well plates and grown to confluence. To inhibit proliferation of cells in wound healing scratch assay, confluent MSCs were treated with mitomycin C (10 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h. Monolayer cells were scratched with a cell scraper and detached cells were removed by washing with culture media. After 12 h of incubation, their migration capacity was assessed under a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a ×40 objective lens.

Invasion assay

The invasion capacity of MSCs was analyzed using Matrigel-coated transwell cell culture chambers (8 μm pore size; Sigma-Aldrich). MSCs (1×104 cells) were seeded in the inserts of transwell chambers in serum-free medium, and culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum was maintained in the lower chamber. All samples were incubated for 48 h at 37°C. In the transwell chambers, cells were stabilized with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with 2% crystal violet in 2% ethanol. The lower surface of the transwell chamber contained invasive cells, which were quantified and photographed using a light microscope. Non-invasive cells were discarded with a cotton swab.

Assessment of angiogenic cytokines

The human angiogenic cytokines, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), released from MSCs, were analyzed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The expression of cytokines was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Perkin Elmer).

Murine hindlimb ischemia model

All animal care procedures and experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital (IACUC2013-5) and were performed in accordance with the National Research Council (NRC) Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The experiments were performed on 8-week-male BALB/c nude mice (Biogenomics, Seoul, Korea) maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle at 25°C in accordance with the regulation of Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital. Experiments using a murine hindlimb ischemia model were performed as previously described, with minor modifications (Lee et al., 2015). Ischemia was induced by ligation and excision of the proximal femoral artery and boundary vessels of the mice. No later than 6 h after surgery, MSCs were injected intramuscularly into the ischemic thigh (5×105 cells/100 μL PBS per mouse; five mice per each group). Cells were transplanted into five ischemic injured sites. The ratio of blood perfusion was assessed by measuring the blood flow in the ischemic (left) and non-ischemic (right) limbs on postoperative days 0, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 using laser Doppler perfusion imaging (Moor Instruments, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

At 3 and 28 days post surgery, the ischemic thigh sites were removed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Each tissue sample was embedded in paraffin. Immunofluorescence staining was performed using primary antibodies against PGC-1α (Novus Biological), CD31, (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa488 and Alexa594 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diaminido-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Images were acquired by confocal microscopy (Olympus).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

TUNEL assay was performed using a TdT fluorescein in situ apoptosis detection kit (Trevigen Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. At postoperative day 3, TUNEL assay was performed in the ischemic tissues. Stained sections were observed using a confocal microscope (Olympus).

Histological staining

At 28 days after surgery, the ischemic tissues were removed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. For histological analysis, the tissue sections were stained with Sirius red and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to assess fibrosis and necrosis, respectively. The areas of fibrosis and necrosis were quantified as a percentage using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered to be statistically significant if p<0.05.

RESULTS

Melatonin increases mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by upregulating PGC-1α

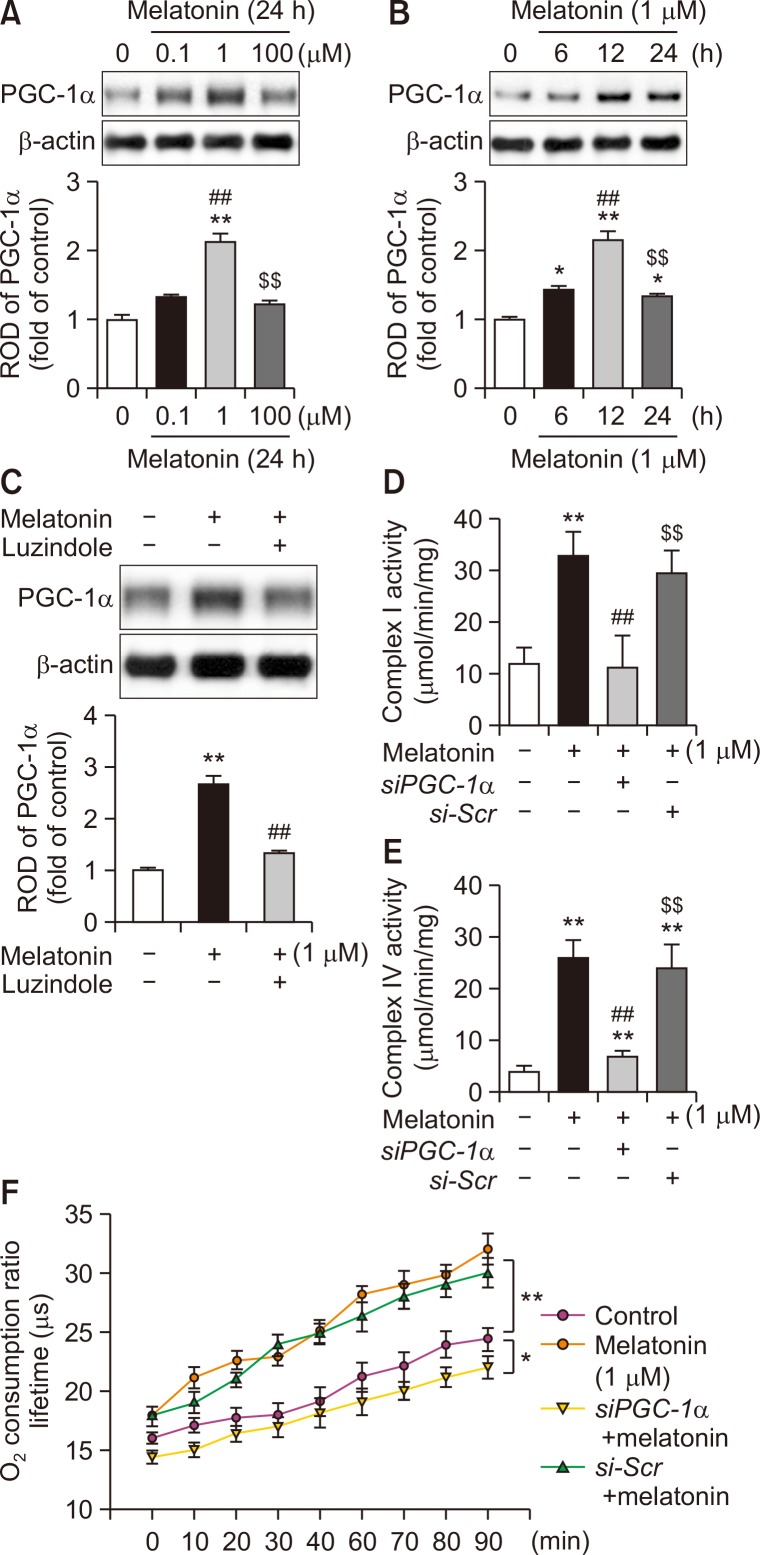

To determine whether melatonin regulates the expression of PGC-1α in MSCs, the level of PGC-1α was assessed after treatment of MSCs with melatonin. Melatonin treatment increased the expression of PGC-1α, while treatment with the melatonin receptor antagonist, luzindole, inhibited this effect (Fig. 1A-1C). These results indicate that melatonin augments the expression of PGC-1α in MSCs. To further investigate whether melatonin is involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in MSCs via PGC-1α signaling, we assessed the activities of mitochondrial complex I and IV and OCR after treatment with melatonin. Treatment of MSCs with melatonin significantly increased the activities of mitochondrial complex I and IV (Fig. 1D, 1E). The mitochondrial OCR was also significantly increased in melatonin-treated MSCs compared with that in control MSCs (Fig. 1F). Enhancement of melatonin-mediated mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in MSCs was blocked by silencing of PGC-1α (Fig. 1D-1F). These findings indicate that melatonin promotes mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in MSCs through upregulation of PGC-1α.

Fig. 1.

Effect of melatonin on PGC-1α-dependent mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in MSCs. (A) Expression of PGC-1α after treatment of MSCs with melatonin (0, 0.1, 1, and 100 μM) for 24 h. The expression level of PGC-1α was determined by densitometry relative to β-actin expression. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. control, ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs treated with melatonin (0.1 μM), and $$p<0.01 vs. MSCs treated with melatonin (1 μM). (B) Expression of PGC-1α after treatment of MSCs with melatonin (1 μM) for 0, 6, 12, or 24 h. The expression level of PGC-1α was determined by densitometry relative to β-actin expression. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs treated with melatonin for 6 h; $$p<0.01 vs. MSCs treated with melatonin for 12 h. (C) After pretreatment with luzindole (melatonin antagonist), the expression of PGC-1α in MSCs treated with melatonin (1 μM) for 12 h was determined by densitometry relative to β-actin expression. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs treated with melatonin alone. (D, E) Activities of mitochondrial complex I and IV in MSCs treated with melatonin. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin; $$p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin+siPGC-1α. (F) Mitochondrial OCR in MSCs treated with melatonin. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

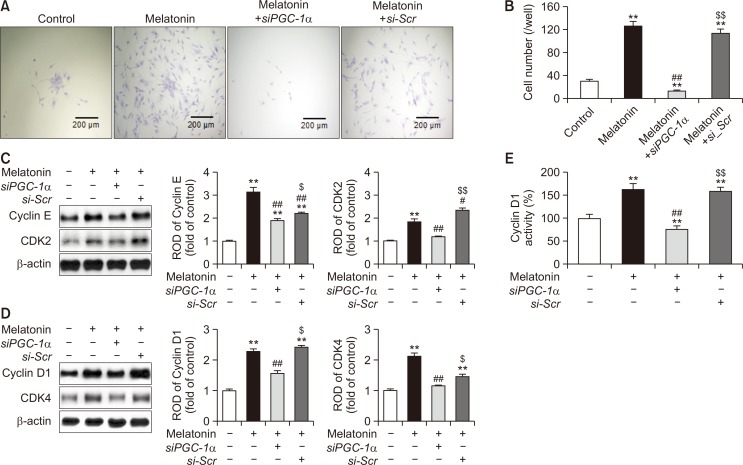

Melatonin enhances the proliferation ability of MSCs via expression of PGC-1α

To examine whether melatonin increases the proliferation ability of MSCs, single cell expansion assay was performed after treatment of MSCs with melatonin. Melatonin treatment significantly promoted the proliferation capacity of MSCs, while knockdown of PGC-1α expression significantly suppressed this effect (Fig. 2A, 2B). To verify whether melatonin regulates the expression of cell cycle-associated proteins in a PGC-1α-dependent manner, we assessed the expression of cyclin E, CDK2, cyclin D1, and CDK4 in melatonin-treated MSCs. Melatonin significantly promoted the expression of cell cycle-associated proteins (Fig. 2C, 2D). In addition, the activity of cyclin D1 was significantly augmented in melatonin-treated MSCs compared with that in untreated MSCs (Fig. 2E). However, silencing of PGC-1α significantly reduced the expression of cell cycle-associated proteins and activity of cyclin D1 in melatonin-treated MSCs (Fig. 2C-2E). These data indicate that melatonin improves the proliferation potential of MSCs by upregulating the expression of PGC-1α.

Fig. 2.

Effect of melatonin on the proliferation ability of MSCs via expression of PGC-1α. (A) Single cell expansion assay in MSCs treated with melatonin. Scale bar=200 μm. (B) The number of cells per well that underwent at least one cell division after 10 days of incubation. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin; $$p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin+siPGC-1α. (C, D) Expression of the cell cycle-related proteins, cyclin E (C), CDK2 (C), cylcin D1 (D), and CDK4 (D), in MSCs treated with melatonin. The expression of cell cycle-related proteins was quantified by densitometry relative to β-actin expression. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. control; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin; $p<0.05, $$p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin+siPGC-1α. (E) Activity of cyclin D1 in MSCs treated with melatonin. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin; $$p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin+siPGC-1α.

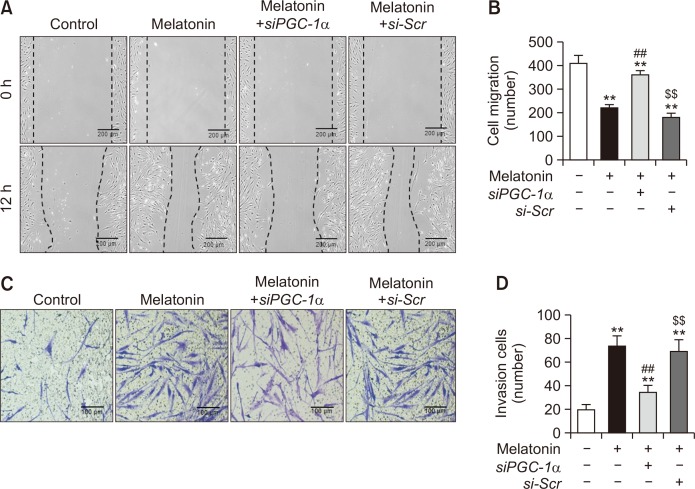

Melatonin promotes mobilization capacity and secretion of angiogenic cytokines in MSCs through upregulation of PGC-1α level

To verify the effect of melatonin on MSC mobilization, we assessed the migration and invasion capacities of MSCs treated with melatonin. The scratched wound healing assay showed that the migration (Fig. 3A, 3B) and invasion capacities (Fig. 3C, 3D) were significantly increased in melatonin-treated MSCs compared with those in untreated MSCs. However, this melatonin-induced increase in migration and invasion capacities was inhibited by silencing of PGC-1α (Fig. 3A-3D). To further reveal whether melatonin modulates the secretion of angiogenic cytokines in MSCs through regulation of PGC-1α expression, the secretion of VEGF, FGF, and HGF was assessed in melatonin-treated MSCs. Melatonin treatment significantly promoted the secretion of angiogenic cytokines in MSCs, whereas knockdown of PGC-1α significantly blocked this effect (Fig. 4A-4C). In addition, to confirm the effect of melatonin-treated MSCs on secretion of the angiogenic cytokines in vivo, we measured the secretion of angiogenic cytokines from the ischemic tissues of murine hindlimb ischemia models using ELISA assay three days after the transplantation of PBS, MSCs, melatonin-treated MSCs (Melatonin+MSC), melatonin-treated MSCs pretreated with PGC-1α siRNA (Melatonin+MSC+siPGC-1α), and melatonin-treated MSCs pretreated with scrambled siRNA (Melatonin+MSC+si-Scr). Consistent with the results in vitro assay (Fig. 4A-4C), the melatonin-treated MSCs markedly enhanced the secretion of the angiogenic cytokines from the ischemic tissues via expression of PGC-1α (Fig. 4D-4F). These results indicate that melatonin enhances the mobilization capacity and secretion of angiogenic cytokines in MSCs by regulating the level of PGC-1α.

Fig. 3.

Melatonin enhances the migration and invasion capacities of MSCs. (A) Scratched wound healing assay in MSCs treated with melatonin. Scale bar=200 μm. (B) The number of migrated cells in MSCs treated with melatonin. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin; $$p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin+siPGC-1α. (C) Transwell invasion assay in MSCs treated with melatonin. Scale bar=100 μm. (D) The number of invaded cells in MSCs treated with melatonin. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin; $$p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin+siPGC-1α.

Fig. 4.

Effect of melatonin on the secretion of angiogenic cytokines in MSCs. (A-C) Secretion of the angiogenic cytokines, VEGF (A), FGF (B), and HGF (C), in MSCs treated with melatonin. Secretion of angiogenic cytokines was assessed by ELISA. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin; $$p<0.01 vs. MSCs+melatonin+siPGC-1α. (D-F) Secretion of the angiogenic cytokines, VEGF (D), FGF (E), and HGF (F), in ischemic tissues after transplantation of PBS, MSCs, melatonin-treated MSCs (Melatonin+MSC), melatonin-treated MSCs pretreated with PGC-1α siRNA (Melatonin+MSC+siPGC-1α), and melatonin-treated MSCs pretreated with scrambled siRNA (Melatonin+MSC+si-Scr) in murine hindlimb ischemia model at postoperative day 3. Secretion of angiogenic cytokines in ischemic tissues was assessed by ELISA. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. PBS; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. MSC; $$p<0.01 vs. Melatonin+MSC.

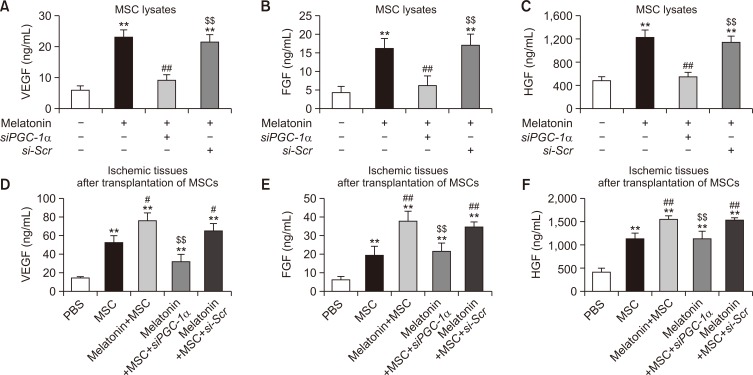

Melatonin improves survival of transplanted MSCs in a murine hindlimb ischemia model via upregulation of PGC-1α expression

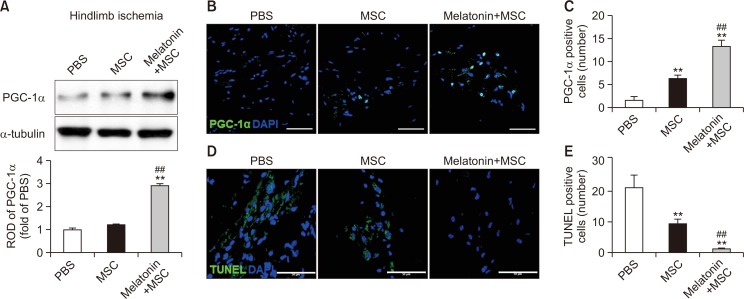

To investigate the effect of melatonin on cell survival in ischemic tissues, we established a murine hindlimb ischemia model and assessed the survival of transplanted MSCs at ischemic sites. At 3 days post operation, we collected the ischemic tissues of mice transplanted with MSCs, and then assessed the expression of PGC-1α. PGC-1α level was significantly increased in mice transplanted with melatonin-treated MSCs compared with that in mice injected with PBS or transplanted with untreated MSCs (Fig. 5A). Immunofluorescence staining for PGC-1α in ischemic tissues also showed that the number of PGC-1α-positive cells was significantly increased in the group transplanted with melatonin-treated MSCs (Fig. 5B, 5C). Apoptosis of transplanted MSCs in the ischemic tissues was significantly decreased in the group transplanted with melatonin-treated MSCs compared with that in other experimental groups (Fig. 5D, 5E). These findings indicate that melatonin augments the survival of transplanted MSCs at ischemic sites through upregulation of PGC-1α expression.

Fig. 5.

Melatonin enhances the survival of transplanted MSCs in ischemic tissues. At postoperative day 3 in a murine hindlimb ischemia model, the ischemic tissues were analyzed for the expression of PGC-1α and apoptosis. (A) Western blot analysis for PGC-1α in ischemic tissues after transplantation of MSCs treated with melatonin. The expression level of PGC-1α was determined by densitometry relative to α-tubulin expression. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. PBS; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs. (B) Immunofluorescence staining for PGC-1α (green) in ischemic tissues after transplantation of MSCs treated with melatonin. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining. Scale bar=50 μm. (C) The number of PGC-1α-positive cells in ischemic tissues. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. PBS; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs. (D) TUNEL assay (green) in ischemic tissues after transplantation of MSCs treated with melatonin. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining. Scale bar=50 μm. (E) The number of TUNEL-positive cells (apoptotic cells) in ischemic tissues. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. PBS; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs.

Melatonin-treated MSCs improve functional recovery in a murine hindlimb ischemia model

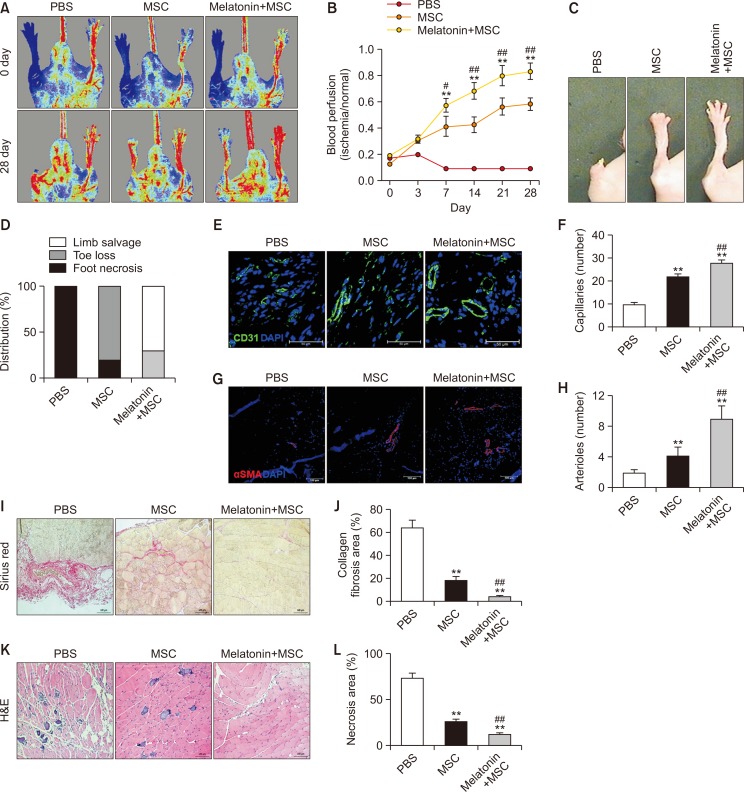

To determine whether melatonin-treated MSCs could promote neovascularization at ischemic sites, blood perfusion and tissue recovery were assessed following transplantation of melatonin-treated MSCs into mice with a hindlimb ischemic injury. The blood perfusion ratio was significantly higher in the group transplanted with melatonin-treated MSCs than that in the other groups (Fig. 6A, 6B). Furthermore, transplantation of MSCs treated with melatonin reduced toe loss and foot necrosis (Fig. 6C, 6D). Immunofluorescence staining for CD31 (capillary) and α-SMA (arteriole) in the ischemic tissues showed that capillary and arteriole densities were significantly increased in the group transplanted with melatonin-treated MSCs compared to those in the other groups (Fig. 6E-6H). In addition, transplantation of MSCs treated with melatonin drastically inhibited the formation of collagen fiber-mediated fibrosis and necrosis in the ischemic tissues (Fig. 6I-6L). These data indicate that transplantation of melatonin-treated MSCs enhances functional recovery, including blood perfusion, limb salvage, neovascularization, and inhibition of fibrosis and necrosis in hindlimb ischemic injury.

Fig. 6.

Assessment of functional recovery in a murine hindlimb ischemia model. (A) Blood perfusion by laser Doppler perfusion imaging in a murine hindlimb ischemia model transplanted with PBS, MSCs, and MSCs treated with melatonin. (B) Blood perfusion ratios. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. PBS; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs. (C) Representative images illustrating various experimental outcomes (limb salvage, toe loss, and foot necrosis) in ischemic limbs at 28 days post operation. (D) Distribution of different outcomes at 28 days post operation. (E) Immunofluorescence staining for CD31 (green) in ischemic limbs at 28 days post operation. Scale bar=50 μm. (F) Standard quantification of capillary density represented as the number of CD31-positive cells. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. PBS; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs. (G) Immunofluorescence staining for α-SMA (red) in ischemic limbs at 28 days post operation. Scale bar=50 μm. (H) Standard quantification of arteriole density represented as the number of CD31-positive cells. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. PBS; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs. (I) Sirius red staining to evaluate collagen fibers in ischemic limbs at 28 days post operation. Scale bar=100 μm. (J) Fibrosis area quantified as the percentage of Sirius red-stained collagen area. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. PBS; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs. (K) H&E staining to evaluated tissue necrosis in ischemic limbs at 28 days post operation. Scale bar=100 μm. (L) Necrosis area quantified as the percentage of necrosis. Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 vs. PBS; ##p<0.01 vs. MSCs.

DISCUSSION

MSCs generally generate basal levels of ROS for maintaining their proliferative potential and multipotent differentiation capacity under physiological conditions. However, excessive generation of ROS and oxidative stress induced by the pathophysiological condition in several chronic diseases, including ischemic disease triggers the impairment of proliferation, survival, and differentiation of MSCs, resulting in progression of senescence, apoptosis, and cell death. To enhance the bioactivities of MSCs for improving their therapeutic effect under pathophysiological conditions, several studies have revealed that melatonin, which serves as a homeostatic component and cell-protective agent, protects MSCs against ischemia, oxidative stress, inflammation, aging, and apoptosis under conditions of ischemic injury (Lee et al., 2017, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Han et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019). In MSCs, melatonin has been shown to increase cell proliferation and self-renewal via melatonin receptor 1B (Lee et al., 2017), and in ischemic thigh tissues, transplantation of melatonin-treated MSCs protected against generation of excessive ROS, resulting in inhibition of apoptosis of transplanted MSCs (Lee et al., 2017). In addition, melatonin has been shown to exert anti-oxidative effect on ischemia-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress through induction of manganese superoxide dismutase 2 and catalase activities (Lee et al., 2019). In chronic kidney disease, melatonin rescues MSCs from uremic toxin-induced cellular senescence by inhibiting mTOR-dependent autophagy (Lee et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). Furthermore, melatonin was shown to reduce cellular senescence of MSCs isolated from patients with chronic kidney disease and enhance their mitochondrial biogenesis through upregulation of cellular prion protein (Han et al., 2019). These findings indicate that melatonin promotes the bioactivities of MSCs against environmental stress by regulating the production of ROS through various cell signaling pathways. In this study, for the first time, we reported that melatonin enhances mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, proliferative potential, migration and invasion capacity, and secretion of angiogenic cytokines in MSCs in a PGC-1α-dependent manner.

Mitochondria play crucial roles in energy production, fatty acid metabolism, calcium signaling, synthesis of metabolites, and cellular apoptosis. PGC-1α is a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, respiration, as well as several metabolic processes (Scarpulla, 2011). PGC-1α is generally activated under harsh conditions, such as limited nutrient availability, cold, and fasting. Once activated, PGC-1α interacts with a variety of transcription factors, leading to regulation of several biological activities under physiological conditions (Scarpulla, 2011). In particular, PGC-1α promotes mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by increasing mitochondrial biogenesis and coordinating mitochondrial remodeling (Austin and St-Pierre, 2012). Several studies have shown that reduced expression of PGC-1α decreases mitochondrial function and increases apoptotic susceptibility (Sano et al., 2004; Adhihetty et al., 2007). ROS-detoxifying enzymes are also regulated by the expression of PGC-1α (St-Pierre et al., 2006). Furthermore, elevated PGC-1α expression protects mitochondria against aging and neurodegenerative disorders by increasing mitochondrial metabolism and detoxification of ROS (Austin and St-Pierre, 2012). Our study indicated that melatonin increased the level of PGC-1α in MSCs, resulting in augmentation of activities of mitochondrial complex I and IV and oxidative phosphorylation. These finding suggest that melatonin-induced PGC-1α expression enhances mitochondrial aerobic respiration in MSCs, leading to an increase in energy metabolism.

Proliferating cells need to generate massive energy to maintain a large amount of biosynthetic macromolecule precursors, such as amino acids and fatty acids, for cell division. Several studies have shown that PGC-1α regulates the mitochondrial energy metabolism pathways involved in maintaining cellular energy homeostasis (Hock and Kralli, 2009; Deblois et al., 2013). In particular, PGC-1α is highly expressed in tissues that demand high energy (Lin et al., 2005). Our results revealed that melatonin increased mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to generate energy via the electron transport chain cycle through upregulation of PGC-1α, leading to augmentation of proliferation capacity of MSCs. The expression of melatonin-induced cell cycle-related proteins was regulated by PGC-1α expression. Especially, our results showed that melatonin regulated the activity of cyclin D1 in a PGC-1α-dependent manner. These findings suggest that elevated expression of melatonin-stimulated PGC-1α facilitates proliferation of MSCs through an increase in mitochondrial metabolism and cell cycle-related protein activity.

A recent study revealed that PGC-1α, as a novel regulator of angiogenesis, plays an important role in vascular development under normal and pathophysiological conditions (Saint-Geniez et al., 2013). PGC-1α regulates the secretion of VEGFA and other angiogenic cytokines in skeletal muscle cells, resulting in enhancement of functional recovery in a murine hindlimb ischemia model (Arany et al., 2008). In addition, alteration of metabolic profiles is involved in angiogenesis, invasion, and migration (Pugh and Ratcliffe, 2003). Consistent with this, our results showed that melatonin-induced PGC-1α expression regulated the migration and invasion capacities of MSCs and secretion of angiogenic cytokines. Although in cancer cells, melatonin acts as an angiogenesis inhibitor through regulation of hypoxia induced factor-1 alpha, other researches have revealed that transplantation of melatonin-treated MSCs improves neovascularization in ischemic diseases (Lee et al., 2017; Han et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019). These findings indicate that the opposite effect of melatonin on angiogenesis might be due to the different cell types and cellular physiology. In this study, we found that melatonin-induced angiogenic effects, such as elevated migration, invasion, and secretion of angiogenic cytokines were dependent on PGC-1α, suggesting that the angiogenic potential of MSCs is regulated by the melatonin-PGC-1α axis. However, to elucidate the relationship between cancer cells and MSCs and the mechanisms underlying melatonin-mediated angiogenesis, further investigations are needed.

Recent studies have indicated the effect of melatonin on MSC-based therapy in ischemic diseases. Melatonin-stimulated MSCs increased functional recovery in hindlimb ischemia via regulation of cellular prion protein (Lee et al., 2017). In addition, melatonin was shown to protect MSCs against ER stress-mediated autophagy, resulting in augmentation of neovascularization in vivo (Lee et al., 2019). In chronic kidney disease, melatonin has been shown to improve the bioactivity of patient-derived MSCs through enhancement of mitochondrial function, leading to enhanced therapeutic effects in hindlimb ischemia patients with chronic kidney disease (Han et al., 2019). Our study showed that melatonin treatment promoted vessel repair and limb salvage in hindlimb ischemia model by increasing the survival of transplanted MSCs in a PGC-1α-dependent manner. Further studies are needed to investigate the therapeutic effect of melatonin-treated MSCs via the PGC-1α pathway in ischemic as well as other chronic diseases, such as chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

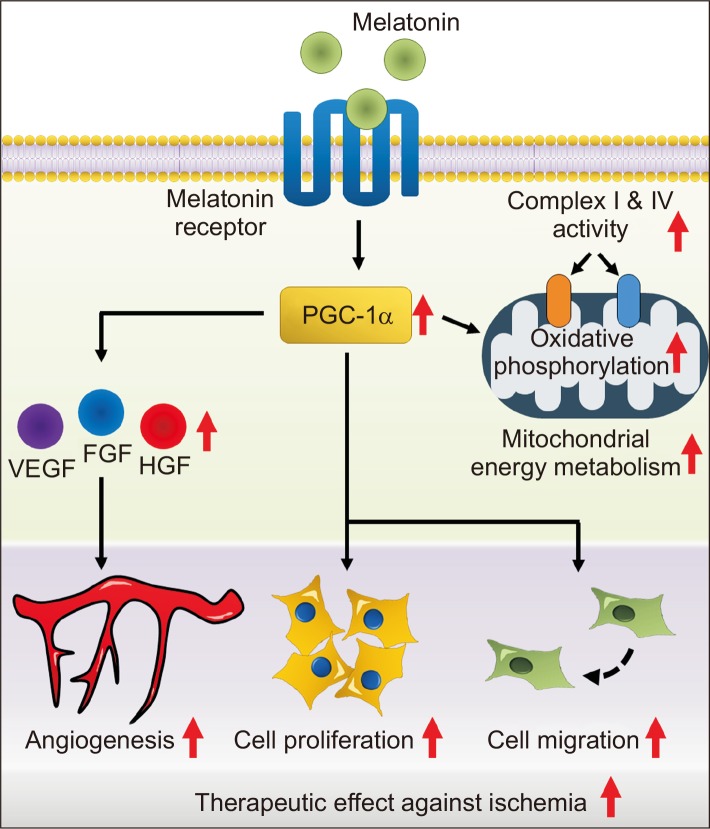

In this study, we reported that melatonin increases the mitochondrial metabolism, proliferative potential, and angiogenic effect of MSCs through upregulation of PGC-1α, thereby improving functional recovery in a hindlimb ischemia model (Fig. 7). These findings suggest that melatonin-induced PGC-1α might be a novel target for developing functional MSC-based therapeutics for patients with ischemic diseases, and melatonin-stimulated MSCs could be used as an effective cell-based medicine for treating ischemic diseases.

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanisms by which melatonin improves the functionality of MSCs through upregulation of PGC-1α. Treatment of MSCs with melatonin promotes mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, proliferation capacity, migration and invasion abilities, and secretion of angiogenic cytokines through upregulation of PGC-1α. As a result, transplantation of MSCs treated with melatonin has improved therapeutic effects, such as inhibition of apoptosis, neovascularization, and tissue repair in ischemic diseases. Thus, melatonin-treated MSCs could be used as a novel cell-based therapeutic option for treating ischemic diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2017M3A 9B4032528). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, publication decision, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Adhihetty P. J., O'Leary M. F., Chabi B., Wicks K. L., Hood D. A. Effect of denervation on mitochondrially mediated apoptosis in skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;102:1143–1151. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00768.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany Z., Foo S. Y., Ma Y., Ruas J. L., Bommi-Reddy A., Girnun G., Cooper M., Laznik D., Chinsomboon J., Rangwala S. M., Baek K. H., Rosenzweig A., Spiegelman B. M. HIF-independent regulation of VEGF and angiogenesis by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha. Nature. 2008;451:1008–1012. doi: 10.1038/nature06613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin S., St-Pierre J. PGC1alpha and mitochondrial metabolism--emerging concepts and relevance in ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:4963–4971. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan A. I., Correa D. The MSC: an injury drugstore. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain G., Fox J., Ashton B., Middleton J. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2739–2749. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblois G., St-Pierre J., Giguere V. The PGC-1/ERR signaling axis in cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32:3483–3490. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A., Ordonez R., Reiter R. J., Gonzalez-Gallego J., Mauriz J. L. Melatonin and endoplasmic reticulum stress: relation to autophagy and apoptosis. J. Pineal Res. 2015;59:292–307. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J. J., Lopez-Pingarron L., Almeida-Souza P., Tres A., Escudero P., Garcia-Gil F. A., Tan D. X., Reiter R. J., Ramírez J. M., Bernal-Pérez M. Protective effects of melatonin in reducing oxidative stress and in preserving the fluidity of biological membranes: a review. J. Pineal Res. 2014;56:225–237. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D., Huang W., Li X., Gao L., Su T., Li X., Ma S., Liu T., Li C., Chen J., Gao E., Cao F. Melatonin facilitates adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells to repair the murine infarcted heart via the SIRT1 signaling pathway. J. Pineal Res. 2016;60:178–192. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. S., Kim S. M., Lee J. H., Jung S. K., Noh H., Lee S. H. Melatonin protects chronic kidney disease mesenchymal stem cells against senescence via PrP(C)-dependent enhancement of the mitochondrial function. J. Pineal Res. 2019;66:e12535. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock M. B., Kralli A. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009;71:177–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan J. E., Reiter R. J., Wasdell M. B., Bax M. The role of the thalamus in sleep, pineal melatonin production, and circadian rhythm sleep disorders. J. Pineal Res. 2009;46:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Han Y. S., Lee S. H. Potentiation of biological effects of mesenchymal stem cells in ischemic conditions by melatonin via upregulation of cellular prion protein expression. J. Pineal Res. 2017;62:doi: 10.1111/jpi.12385. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Lee S. H., Choi S. H., Asahara T., Kwon S. M. The sulfated polysaccharide fucoidan rescues senescence of endothelial colony-forming cells for ischemic repair. Stem Cells. 2015;33:1939–1951. doi: 10.1002/stem.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Yoon Y. M., Han Y. S., Jung S. K., Lee S. H. Melatonin protects mesenchymal stem cells from autophagy-mediated death under ischaemic ER-stress conditions by increasing prion protein expression. Cell Prolif. 2019;52:e12545. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Yun C. W., Hur J., Lee S. H. Fucoidan rescues p-cresol-induced cellular senescence in mesenchymal stem cells via FAK-Akt-TWIST axis. Mar. Drugs. 2018;16:E121. doi: 10.3390/md16040121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Liu C., Li N., Hao T., Han T., Hill D. E., Vidal M., Lin J. D. Genome-wide coactivation analysis of PGC-1alpha identifies BAF60a as a regulator of hepatic lipid metabolism. Cell Metab. 2008;8:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Handschin C., Spiegelman B. M. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab. 2005;1:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv F. J., Tuan R. S., Cheung K. M., Leung V. Y. Concise review: the surface markers and identity of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1408–1419. doi: 10.1002/stem.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauriz J. L., Collado P. S., Veneroso C., Reiter R. J., Gonzalez-Gallego J. A review of the molecular aspects of melatonin's anti-inflammatory actions: recent insights and new perspectives. J. Pineal Res. 2013;54:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J. Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: role of the HIF system. Nat. Med. 2003;9:677–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J. Pineal melatonin: cell biology of its synthesis and of its physiological interactions. Endocr. Rev. 1991;12:151–180. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-2-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Mayo J. C., Tan D. X., Sainz R. M., Alatorre-Jimenez M., Qin L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: under promises but over delivers. J. Pineal Res. 2016;61:253–278. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Tan D. X., Manchester L. C., Paredes S. D., Mayo J. C., Sainz R. M. Melatonin and reproduction revisited. Biol. Reprod. 2009;81:445–456. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Geniez M., Jiang A., Abend S., Liu L., Sweigard H., Connor K. M., Arany Z. PGC-1alpha regulates normal and pathological angiogenesis in the retina. Am. J. Pathol. 2013;182:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano M., Wang S. C., Shirai M., Scaglia F., Xie M., Sakai S., Tanaka T., Kulkarni P. A., Barger P. M., Youker K. A., Taffet G. E., Hamamori Y., Michael L. H., Craigen W. J., Schneider M. D. Activation of cardiac Cdk9 represses PGC-1 and confers a predisposition to heart failure. EMBO J. 2004;23:3559–3569. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpulla R. C. Metabolic control of mitochondrial biogenesis through the PGC-1 family regulatory network. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1813:1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J., Drori S., Uldry M., Silvaggi J. M., Rhee J., Jager S., Handschin C., Zheng K., Lin J., Yang W., Simon D. K., Bachoo R., Spiegelman B. M. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S. C., Hsieh M. J., Yang W. E., Chung W. H., Reiter R. J., Yang S. F. Cancer metastasis: mechanisms of inhibition by melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2017;62:doi: 10.1111/jpi.12370. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip H. K., Chang Y. C., Wallace C. G., Chang L. T., Tsai T. H., Chen Y. L., Chang H. W., Leu S., Zhen Y. Y., Tsai C. Y., Yeh K. H., Sun C. K., Yen C. H. Melatonin treatment improves adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy for acute lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Pineal Res. 2013;54:207–221. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B., Huo L., Liu Y., Deng P., Szymanski J., Li J., Luo X., Hong C., Lin J., Wang C. Y. PGC-1alpha controls skeletal stem cell fate and bone-fat balance in osteoporosis and skeletal aging by inducing TAZ. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:193–209.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Hao J., Zheng Y., Su R., Liao Y., Gong X., Liu L., Wang X. Fucoidan protects dopaminergic neurons by enhancing the mitochondrial function in a rotenone-induced rat model of Parkinson's disease. Aging Dis. 2018;9:590–604. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Lu T., Xie T. A PGC-1 tale: healthier intestinal stem cells, longer life. Cell Metab. 2011;14:571–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]