Introduction

Over the last 25 years there has been interest in understanding brain function in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Autism was first described by Leo Kanner in 1943 (Kanner 1943) and is characterized by deficits of social communication, interaction, and restricted and repetitive interests manifest in multiple situations and contexts (American Psychiatric Association [APA] 2013). In recent years, the prevalence of ASD has been on the rise, with current estimates of 1 in 40 children in the United States with autism (Kogan et al. 2018). As a result of the cognitive deficits common in ASD, many children with ASD require special education or therapeutic services. It is estimated that 89% of children with ASD receive special education services, with only 20% receiving services before the age of 2 (Kogan et al. 2018). The societal and personal costs of ASD on affected individuals and families make elucidating the underlying causes of the disorder a top research priority.

A diagnosis of ASD is made via observation by trained clinicians. The median age of ASD diagnosis in the United States is 4 years old (Baio et al. 2018). At present, there is no ASD brain imaging marker for clinical use. Individuals with ASD are not referred for clinical radiology exams except in cases where there are comorbid medical concerns (e.g., epilepsy, tuberous sclerosis). Neuroimaging, however, has often been proposed as a way to reduce diagnostic subjectivity as well as to identify at-risk infants who will go on to develop ASD.

Noninvasive, passive imaging techniques that do not require patient cooperation allow for easier assessment of difficult to assess populations (e.g., infants, children, individuals with language or intellectual impairment). Magnetoencephalography (MEG) can be used in infants and young children and does not make any sound during measurement. MEG has the temporal resolution required to measure neural processing associated with incoming sensory information as well as for evaluating real-time cortical activity such as resting-state brain activity. As detailed below, active areas of research seek neurophysiological diagnostic or prognostic measures of autism.

Candidate brain markers of ASD

MEG research in the field of ASD is extensive, covering multiple sensory and cognitive modalities. Given space limitations, rather than provide an exhaustive review of all ASD MEG research, this chapter focuses on two areas of very active research: auditory processes and resting state activity in ASD.

Numerous studies have revealed auditory processing and resting state abnormalities in individuals with ASD (Berman et al. 2016, Edgar et al. 2014, Edgar et al. 2015a, Edgar et al. 2015b, Gage et al. 2003a, Matsuzaki et al. 2019a, Matsuzaki et al. 2019b, Oram Cardy et al. 2005b, Port et al. 2015, Roberts et al. 2010, Roberts et al. 2011, Roberts et al. 2013, Yoshimura et al. 2017). Demonstrating these abnormalities at the single-subject level in children with ASD could lead to identifying neurophysiological “red flags” in infants and toddlers, long before clinical interviews identify children with ASD. Several candidate MEG “markers” are described.

M50 and M100

N100 and its magnetic equivalent N100m or M100, is a middle latency auditory evoked potential occurring approximately 100 ms following stimulus presentation. The auditory M100 response is regarded as an index of early sound perception and feature encoding, and is bilaterally generated in Heschl’s gyrus and the planum temporale (Hari 1990, Lütkenhöner and Steinsträter 1998). M100 latency decreases and amplitude increases as a function of age (Edgar et al. 2014, Oram Cardy et al. 2005a, Paetau et al. 1995, Roberts et al. 2010), although in infants, toddlers and young children, M100 is not always observed (Edgar et al. 2014). However, by 10–12 years of age, adult-like M100 is observed in over 80% of children (Edgar et al. 2014, Ponton et al. 2000). M100 matures faster in the right hemisphere, with earlier latencies and larger amplitudes apparent at earlier time points in the right than left hemisphere (Edgar et al. 2014). M100 latency and amplitude are modulated by stimulus duration, intensity, or frequency with mid-frequency sounds (1–3 kHz) resulting in earlier M100 responses than lower frequency (100–200 Hz) sounds (Roberts and Poeppel 1996, Roberts et al. 2000). This M100 latency difference has been termed ‘dynamic range’ and is approximately 10–15 ms in typically developing (TD) individuals (Roberts et al. 2000).

Although a small response in adults, the P50 or M50 is much more likely than the M100 to be observed in infants and young children, with a peak latency of 86–95 ms in 5–6 year-olds (Wunderlich and Cone-Wesson 2006). MEG studies indicate M50 is generated in the left and right superior temporal gyrus ([STG] (Huotilainen et al. 1998, Mäkelä et al. 1994, Pelizzone et al. 1987, Reite et al. 1988, Yoshiura et al. 1995, Yvert et al. 2001). Maturation of M50 occurs bilaterally, with both latency and amplitude decreasing with age (Paetau et al. 1995).

Several studies show later M50 (Edgar et al. 2014, Roberts et al. 2013) and M100 latencies in individuals with ASD compared to TD controls, indicating delayed sound perception (Edgar et al. 2014, Edgar et al. 2015a, Gage et al. 2003a, Port et al. 2015, Roberts et al. 2010, Roberts et al. 2013, Matsuzaki et al. 2012). In a study of 25 children with ASD and 17 TD comparison children, Roberts et al., (2010) found increased M100 latency in individuals with ASD in response to sinusoidal tones. The right-hemisphere response to the 500 ms tone was a fair predictor of ASD (75% sensitivity, 81% specificity). These findings were replicated in a larger sample by Edgar et al. (2015a), examining 52 children with ASD and 63 TD children 6–14 years of age. When a subset of children from these studies (ASD: 7; TD: 9; mean age 12.1 years) were recruited to a longitudinal study, the latency differences found at earlier time points were again observed 2–5 years later (Port et al. 2015). Other studies have observed that the expected negative relationship between M100 latency and age is either absent in ASD (Roberts et al. 2010) or observed only in the left hemisphere (Gage, Siegel and Roberts 2003b). Finally, in comparison with TD controls, individuals with ASD demonstrate a reduced right-hemisphere dynamic range (~ 6 ms) indicating reduced sensitivity to spectral contrasts (Gage et al., 2003a; see Figure 1).

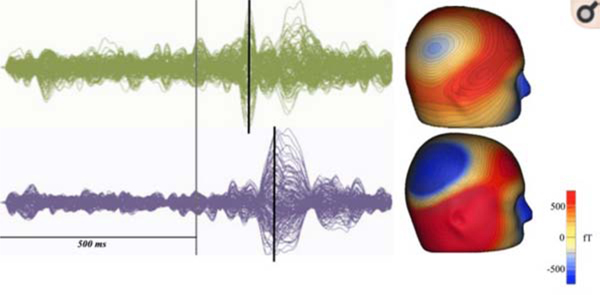

Figure 1.

Representative child with ASD (bottom) shows a delayed M100 response compared to an age-matched typically developing control (top). At left, sensor overlay plots show the auditory evoked response from a typically developing child (green) and a child with ASD (purple). The stimulus onset is marked in gray and the M100 response shown with the black line. At right, M100 magnetic field maps (top: TD; bottom: ASD) From RG Port, AR Anwar, M Ku, et al. Prospective MEG biomarkers in ASD: pre-clinical evidence and clinical promise of electrophysiological signatures. Yale J Biol Med 2015. Mar 4;88(1): p.27; with permission.

Of clinical interest is the relationship between neurophysiology and behavior. As efficient processing of auditory input is crucial for developing language, measuring neurophysiological responses to sound in individuals with ASD offers insight into how differences in brain function impact behavior. There is some evidence that M50 predicts language impairment (Oram Cardy et al. 2008). This, however has not been found across studies (Roberts et al. 2010). A delayed M100 latency has also been associated with language impairment in ASD, however, it is not reflective of idiopathic language impairment (Roberts et al. 2012). Recent data from Roberts et al (2019) indicated that profoundly delayed M50 and M100 latencies are found in individuals with ASD who are minimally verbal / nonverbal (MVNV) compared to TD children and higher functioning children with ASD. Nonetheless the specificity of M50/M100 delays for language vs cognitive impairments has not been clearly established.

MMF

The auditory EEG recorded mismatch negativity (MMN) and its MEG equivalent, the magnetic mismatch field (MMF), are neurophysiological indices of auditory change detection (Näätänen, Gaillard and Mäntysalo 1978, Näätänen et al. 2007, Schwartz, Shinn-Cunningham and Tager-Flusberg 2018). During a train of standard sounds, the MMN/F occurs in response to an unexpected deviant stimulus (e.g., /α/, /α/, /α/, /u/) that violates sensory expectation (Näätänen et al. 2007, Näätänen 1992). As such, the MMN/F has been proposed as an index of auditory memory (Alho 1995, Näätänen et al. 2007). In adults, the MMN occurs between 170 and 250 ms post-stimulus onset, even in the absence of overt attention to the stimulus (Näätänen et al. 2007). MMN can be elicited by a change in pitch, duration, or intensity (Näätänen 1992, Näätänen et al. 2007) and can even occur as a function of interstimulus interval (ISI) change (Ford and Hillyard 1981). In experiments involving newborns, auditory MMN latency is slightly later (Cheour et al. 1998, Cheour-Luhtanen et al. 1996, Cheour et al. 1997, Kurtzberg et al. 1995) and MMN amplitude smaller (Aaltonen et al. 1987, Cheour et al. 1997) than older children and adults. MMN latency corresponds to an adult-like latency by the time children are school age (Csépe 1995, Kraus et al. 1992). Research has shown that auditory MMF signals originate from the temporoparietal cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Alho 1995, Handy 2005). The difference wave, which permits the most robust identification of the MMN component, is identified by subtracting mean responses to deviant stimuli from mean responses to standard stimuli (Luck 2005).

MEG studies utilizing the MMF have explored auditory perception of tones and speech sounds in children on the autism spectrum. School-age ASD populations and adults with ASD show MMF differences in response to pure tone and vowel changes versus age-matched controls (Berman et al. 2016, Matsuzaki et al. 2017, Matsuzaki et al. 2019a, Matsuzaki et al. 2019b, Oram Cardy et al. 2005b, Roberts et al. 2011, Yoshimura et al. 2017).

Oram Cardy et al. (2005b) examined the MMF in 7 children with ASD and 9 TD children 8–17 years of age. During the experiment, children were presented with pure tones (300 ms; 300 and 700 Hz; ISI 400 ms) and synthesized vowels /α/ and /u/ (300 ms, F1 = 310 and 710 Hz respectively; ISI 400 ms) in an oddball paradigm in which trains of standard stimuli were followed by intermittent deviant stimuli (standard = 85%, deviant =15%). MMF amplitudes were not significantly different between groups; however, a delayed MMF response was found in the ASD group in response to all stimuli. The authors speculated that slower auditory change detection may be associated with language impairment in children with ASD (Oram Cardy et al. 2005b).

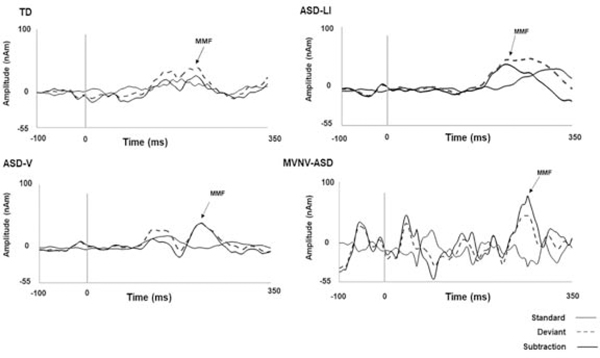

A study by Roberts et al. (2011) looked at MMF responses to pure tones and vowels in 18 children with ASD and language impairment, 33 children with ASD without language impairment, and 27 age-matched comparison children (8–11 years). Tone and vowel stimuli were the same as Oram Cardy (2005b). In both the tone and vowel condition, the authors found a significantly later MMF latency in the full sample of children with ASD compared to TD peers, and a significantly later MMF latency in children with ASD and concomitant language impairment compared to children with ASD without language impairment. These findings coincide with those of Oram Cardy and colleagues (2005b) and offer further evidence that auditory perceptual differences in ASD and language impairment are not specific to speech sounds but also apply to simple tones. Using receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis, the authors tested the sensitivity and specificity of mean MMF latency as a diagnostic indicator of language impairment in ASD. Sensitivity was found to be 82.4% and specificity was 71.2% (Roberts et al. 2011). These results were again replicated with an additional cohort of 8–12 year old minimally verbal/non-verbal children with ASD (Matsuzaki et al. 2019b), as well as in young adults with ASD during an auditory oddball paradigm with vowel stimuli (Matsuzaki et al., 2019a; see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Source response waveforms from superior temporal gyrus. Vertical lines indicate stimulus onset (0 ms). Arrows indicate MMF latency in a representative TD child (182 ms), verbal ASD without language impairment (214 ms), ASD and language impairment (222 ms), and ASD MVNV (270 ms). The solid gray line indicates the standard response, the dashed gray line indicates the deviant response, and the solid black line their subtraction to yield the difference wave. From Matsuzaki, J., E. S. Kuschner, L. Blaskey, et al. Abnormal auditory mismatch fields are associated with communication impairment in both verbal and minimally verbal/nonverbal children who have autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res 2019. Aug;12(8):1225–1235; with permission.

Although delayed MMF latency has been associated with language impairment across studies, further research is needed to determine if MMF is associated primarily with language impairment concomitant with ASD or with general language impairment/delay. A small study by Roberts et al. (2012) suggested that similar MMF delays were observed in SLI, suggesting that MMF latency delay is associated with language impairment, independent of ASD diagnosis. A recent study showing MMF latency delay in boys with 47,XYY syndrome (independent of ASD diagnosis) also supported the general association of MMF latency delay with language impairment (Matsuzaki 2019c).

Auditory Gamma-Band Activity

Auditory gamma-band STG activity has also been proposed as a marker of ASD. In TD individuals gamma-band steady-state responses can be observed following trains of auditory stimuli (tones, clicks) and reflect local connectivity. Steady-state gamma is greatest when auditory stimuli are modulated at 40 Hz (Boettcher et al. 2001, Boettcher et al. 2002, Hari, Hämäläinen and Joutsiniemi 1989, Stapells et al. 1984), with the primary steady-state auditory generators in left and right primary/secondary auditory cortex (Wilson et al. 2007). Differences in post-stimulus auditory gamma-band activity have been found in individuals with ASD compared to those with typical development (Edgar et al. 2015b, Gaetz et al. 2014, Gandal et al. 2010, Port et al. 2015, Tanigawa et al. 2018, Wilson et al. 2007) as well as in first degree relatives of individuals with ASD (McFadden et al. 2012, Rojas et al. 2008). Wilson et al. (2007) found reduced 40 Hz left hemisphere gamma-band activity in individuals with ASD during a 40 Hz click train task. When presenting participants with 1000 Hz tones, Rojas et al. (2008), also found decreased bilateral 40 Hz early STG gamma-band inter-trial coherence (ITC) in adults with ASD and their parents.

In a study of 105 children with ASD and 36 TD controls, Edgar et al. (2015b) found smaller increases in bilateral gamma evoked activity from 50–150 ms in ASD compared to TD children in response to randomly presented sinusoidal tones (300 ms; 200, 300, 500, & 1000 Hz, ISI 1000 ms) as well as bilateral decreases in gamma ITC from 50 to 200 ms (300, 500, and 1000 Hz). Low-frequency inter-trial coherence (below 20 Hz) was also decreased after 50 ms (200, 300, and 500 Hz) in ASD. With the exception of right high gamma, bilateral 30–50 Hz prestimulus power was greater in individuals with ASD for all stimuli. These increases in left and right 4–80 Hz pre-stimulus activity were associated with delayed M100 latency. Increased right hemisphere 30–50 Hz pre-stimulus activity as well as left hemisphere 100 Hz post-stimulus gamma were associated with decreased language scores (Edgar et al., 2015b; see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of Clinical Evaluation of Language-Fourth Edition (CELF-4), Core language index scores (x-axis) and right STG pre-stimulus gamma activity (y-axis, 30–50 Hz) in individuals with ASD. In ASD lower CELF-4 scores were associated with increased right-hemisphere pre-stimulus gamma activity. From Edgar, J. C., S. Y. Khan, L. Blaskey, et al. Neuromagnetic oscillations predict evoked-response latency delays and core language deficits in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2015; 45(2):395–405; with permission.

Support for the hypothesis that gamma-band oscillatory activity reflects local neural circuitry is provided by the emerging association between gamma-band activity and MRS-determined estimates of gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA), as an index of inhibitory tone. (Balz et al. 2016, Edden et al. 2009, Gaetz et al. 2011, Muthukumaraswamy et al. 2009, Port et al. 2017). This is particularly relevant to ASD, as the seminal work of Rubenstein and Merzenich (2003) hypothesized that ASD symptomatology, at least in part, stems from an imbalance of cortical excitatory and inhibitory (E/I) neurotransmission (Port, Oberman and Roberts 2019). This is supported yet further by evidence of diminished GABA in ASD, with regional dependence most pronounced in temporal and posterior frontal/parietal regions (Gaetz et al. 2014).

Auditory Alpha and Beta-Band Activity

Another promising area of research examines event related desynchrony (ERD), or decreased synchrony within a specific frequency band following the presentation of a stimulus (Neuper and Pfurtscheller 2001). Studies have shown that theta, alpha, and beta ERD changes occur in response to auditory, written language, and memory tasks (Brennan et al. 2014, Krause, Pesonen and Hämäläinen 2007, Pesonen et al. 2006, Tavabi, Embick and Roberts 2011). Specifically during semantic priming tasks, alpha and beta ERDs are reduced 200+ ms following stimulus onset when the target word is related to the prime (Brennan et al. 2014). It has been suggested that alpha ERD is associated with lexical retrieval with larger ERDs indicating longer lexical search time (Brennan et al. 2014, Tavabi et al. 2011).

In a study of 51 children with ASD and 19 TD children 6–11 years of age, Bloy et al. (2019) found that increased theta, alpha, and beta band (5–20 Hz) ERD 200–1000 ms post stimulus (word and plausible nonword) were correlated with better language assessment scores but not with ASD group allocation, symptom severity, or IQ. These results were true for words and plausible nonwords. Since a plausible nonword (e.g., blick) would likely trigger a search of the lexicon similar to that of a real word, results support the use of ERD as a measure of lexical search time. Thus, 5–20 Hz ERDs have the potential to be used as a clinical measure of lexical access in ASD (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Sensory waveforms grand-averaged across subject and token, time-locked to token onset. Shaded area (red) indicates the time window used in ERD measurements. (b) Grand average spectro-temporal plots (TFR’s) for the left and right auditory cortex source locations. From L Bloy, K Shwayder, L Blaskey, et al. A Spectrotemporal Correlate of Language Impairment in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2019; Aug 49(8): 3181–3190; with permission.

Resting State Alpha

Eyes-closed resting-state tasks have been used to study neural oscillations in ASD. Oscillatory activity results from large numbers of simultaneously firing neurons, and is thought to mediate a broad spectrum of cortical activity (for reviews see Uhlhaas et al. 2009, Wang 2010). Alpha oscillations (8–13 Hz) are the dominate brain oscillation during the eyes-closed resting state (Berger 1929, Edgar et al. 2015b, Haegens et al. 2014, Hari and Salmelin 1997). Resting-state alpha activity is most prominent in parietal-occipital regions (Ciulla, Takeda and Endo 1999, Hari and Salmelin 1997, Niedermeyer 1993a, Salmelin and Hari 1994), and alpha activity increases as a function of age in TD individuals (Alvarez Amador et al. 1989, Chiang et al. 2011, Cragg et al. 2011, Epstein 1980, Gibbs and Knott 1949, Hughes 1987, John et al. 1980, Klimesch 1999, Niedermeyer 1993b, Miskovic et al. 2015, Somsen et al. 1997, Stroganova, Orekhova and Posikera 1999). MEG studies have isolated parietal-occipital regions, especially near primary visual cortex, as the area with the strongest resting-state alpha generators (Bouyer, Tilquin and Rougeul 1983, Hari and Salmelin 1997, Huang et al. 2014, Salmelin and Hari 1994). Several studies have shown differences in resting-state alpha activity in children with ASD compared to TD individuals (Cornew et al. 2012, Edgar et al. 2015b, Edgar et al. 2019).

Cornew et al. (2012) explored resting-state activity in 27 children with ASD and 23 TD children ages 6–15 years. Findings included increased delta, theta, and high frequency power in ASD. Alpha power, specifically in the temporal and parietal regions, was also increased in ASD compared to TD, and these increases were correlated with ASD symptoms (Cornew et al. 2012). Edgar et al. (2015b) assessed alpha activity in 41 children with ASD and 47 TD children ages 614 years of age. Results demonstrated increased alpha activity bordering the central sulcus and parietal association cortices in ASD versus TD (see Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

Scatterplots showing associations between age (x axis) and peak alpha frequency (y axis) for TDC (blue) and ASD (red). As detailed in Section 3, a significant interaction term indicated group slope differences. ***p < 0.001. From JC Edgar, M Dipiero, E McBride. Abnormal maturation of the resting-state peak alpha frequency in children with autism spectrum disorder. Hum Brain Mapp 2019. Aug 1;40(11):3288–3298; with permission.

Figure 6.

(a) Scatterplots showing associations between nonverbal IQ (x axis) and peak alpha frequency (y axis) for TDC (blue) and ASD (red). (b) Nonverbal IQ and peak alpha frequency associations shown for the younger (<10-years-old; left plot) and older children (>10-years-old; right plot). *p < 0.05. From JC Edgar, M Dipiero, E McBride. Abnormal maturation of the resting-state peak alpha frequency in children with autism spectrum disorder. Hum Brain Mapp 2019. Aug 1;40(11):3288–3298; with permission.

Increased alpha activity is also of clinical interest, with increased deficits in social responsiveness associated with increased left central sulcus alpha activity and with more typical social behaviors associated with greater calcarine region alpha activity in ASD. Also of interest, peak alpha frequency did not increase with age in individuals with ASD, indicating abnormal patterns of alpha maturation in ASD compared to TD children (Edgar et al. 2015b). These peak alpha frequency results were replicated in a large cohort of male children (ASD: 183; TD: 121) ages 6–17 years, with peak alpha frequency group differences most prominent in the younger children with ASD than the TD children (6–10 years) (Edgar et al. 2019).

Potential future roles for MEG in the clinical management of ASD

Until recently, MEG research has focused on older children and adults. However, the recent development of MEG scanners with a sensor helmet sized for young infants is resulting in a greater number of MEG infant studies. Longitudinal research on infants at-risk for ASD (baby siblings of children with ASD) is needed to determine if the neurophysiological differences found in school-age children with ASD are apparent before a child is formally diagnosed with ASD. If infant MEG measures are found to predict language and ASD outcomes at age three, these measures could be developed into diagnostic or predictive measures for infants.

It is of note that, to date, MEG ASD studies have focused on reporting group differences. Although these studies are necessary to show research directions worth pursuing, MEG markers will need to show good sensitivity and specificity to be of clinical use. To this end, the use of normative databases (with concomitant standardization of data collection and analysis methods) is needed to determine if individuals with ASD can be identified at the individual level. It is also likely that multiple MEG measures (auditory, visual, social, resting state) can be combined to predict ASD with more accuracy than a single measure, with machine learning approaches used to identify the combination of measures that best differentiate infants and children with and without ASD.

MEG markers may also offer prognostic information (e.g., will a child have difficulty developing language?) and thus allow targeted treatment (behavioral and pharmaceutical), based on an individual’s neurophysiological profile. MEG also has the potential to assess the efficacy of ASD treatments; via determining if brain neural activity is changing in response to treatment clinicians may be better positioned to decide whether to continue or terminate treatment.

To conclude, although more research is needed before clinical MEG exams are available for ASD, current MEG research indicates several markers of clinical interest. Work is needed to identify diagnostic or prognostic ASD markers that provide good sensitivity and specificity at the individual level.

Key Points:

MEG is not currently used clinically for diagnosis of ASD.

Passive MEG paradigms are well-suited for obtaining information on cortical function in children with ASD and thus have the potential for clinical use.

Research has shown event-related and resting state electrophysiological differences in individuals with ASD.

Further research is needed in order to determine the diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic usefulness of MEG in this area.

Synopsis.

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) offers insight into functional brain processing in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Research has shown that individuals with ASD have delayed M50, M100, and MMF latencies in response to sounds compared to typically developing (TD) individuals. Whereas M50 and M100 latencies are associated with cognitive function, MMF latencies are associated with language ability. STG 40 Hz gamma activity has also be found to be abnormal in ASD, with decreased primary/secondary auditory cortex gamma and low-frequency inter-trail coherence (ITC) in individuals with ASD compared to controls, and with gamma abnormalities associated with poorer performance on language tests. Increased event-related desynchrony (ERD) to words has been associated with language ability in individuals with ASD and TD and has been proposed as an index of lexical retrieval. With respect to resting-state activity, abnormal maturation of the peak alpha frequency and increased resting-state alpha activity have been repeatedly observed in ASD. Although the clinical use of MEG in diagnosing ASD is currently limited, the above evidence suggests that passive MEG paradigms are especially suited for obtaining information on cortical function in children with ASD. Further research is needed in order to determine the diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic usefulness of MEG in this area.

Acknowledgments

Writing this chapter was supported in part by NIH grants R01DC008871 (TR), R21NS106135 (TR), R21MH109158 (TR), R01MH107506 (JCE), R21MH098204 (JCE), R21NS090192 (JCE), NICHD grant R01HD093776 (JCE), and the Clinical Translational Core, Biostatistics & Bioinformatics Core and the Neuroimaging Core of the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center funded by NICHD grant 5U54HD086984 (Neuroimaging and neurocircuitry core director: TR; overall PI: M. Robinson, PhD). Dr. Roberts gratefully acknowledges the Oberkircher Family for the Oberkircher Family Chair in Pediatric Radiology at CHOP.

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER: Dr. Roberts declares his position on the advisory boards of 1) CTF MEG, 2) Ricoh, 3) Spago Nano Medical and 4) Prism Clinical Imaging and consulting arrangements with Avexis Inc. and Acadia Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Roberts and Dr. Edgar also declare intellectual property relating to the potential use of electrophysiological markers for treatment planning in clinical ASD.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aaltonen O, Niemi P, Nyrke T & Tuhkanen M (1987) Event-related brain potentials and the perception of a phonetic continuum. Biol Psychol, 24, 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alho K (1995) Cerebral generators of mismatch negativity (MMN) and its magnetic counterpart (MMNm) elicited by sound changes. Ear Hear, 16, 38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez Amador A, Sosa P. A. Valdés, Marqui R. D. Pascual, Garcia L. Galan, Lirio R. Biscay & Bayard J. Bosch (1989) On the structure of EEG development. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 73, 10–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA], D.-T. F. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th Ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Baio J, Wiggins L, Chistenson DL, Maenner MJ, Daniels J, Warren Z, Kurzius-Spencer M, Zahorodny W, Rosenberg CR, White T, Durkin M, Imm P, Nikolau L, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Lee LC, Harrington R, Lopez M, Fitzgerald RT, Hewitt A, Pettygrove S, Constantino JN, Vehorn A, Shenouda J, Hall-Lande J, Van Naarden Braun K & Dowling N (2018) Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States,2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balz J, Keil J, Romero Y. Roa, Mekle R, Schubert F, Aydin S, Ittermann B, Gallinat J & Senkowski D (2016) GABA concentration in superior temporal sulcus predicts gamma power and perception in the sound-induced flash illusion. Neuroimage, 125, 724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger H (1929) Hans Berger on the electroencephalogram of man. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten, 87, 527–570. [Google Scholar]

- Berman JI, Edgar JC, Blaskey L, Kuschner ES, Levy SE, Ku M, Dell J & Roberts TP (2016) Multimodal Diffusion-MRI and MEG Assessment of Auditory and Language System Development in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Neuroanat, 10, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloy L, Shwayder K, Blaskey L, Roberts TPL & Embick D (2019) A Spectrotemporal Correlate of Language Impairment in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord, 49, 3181–3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher FA, Madhotra D, Poth EA & Mills JH (2002) The frequency-modulation following response in young and aged human subjects. Hear Res, 165, 10–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher FA, Poth EA, Mills JH & Dubno JR (2001) The amplitude-modulation following response in young and aged human subjects. Hear Res, 153, 32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer JJ, Tilquin C & Rougeul A (1983) Thalamic rhythms in cat during quiet wakefulness and immobility. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 55, 180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J, Lignos C, Embick D & Roberts TP (2014) Spectro-temporal correlates of lexical access during auditory lexical decision. Brain Lang, 133, 39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheour M, Ceponiene R, Lehtokoski A, Luuk A, Allik J, Alho K & Näätänen R (1998) Development of language-specific phoneme representations in the infant brain. Nat Neurosci, 1, 351–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheour M, A. K., S. K., R. K., R. M., A. O., E. O. & Näätänen R (1997) The mismatch negativity to speech sounds at the age of three months. Developmental Neurophysiology, 13, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cheour-Luhtanen M, Alho K, Sainio K, Rinne T, Reinikainen K, Pohjavuori M, Renlund M, Aaltonen O, Eerola O & Näätänen R (1996) The ontogenetically earliest discriminative response of the human brain. Psychophysiology, 33, 478–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang AK, Rennie CJ, Robinson PA, van Albada SJ & Kerr CC (2011) Age trends and sex differences of alpha rhythms including split alpha peaks. Clin Neurophysiol, 122, 1505–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciulla C, Takeda T & Endo H (1999) MEG characterization of spontaneous alpha rhythm in the human brain. Brain Topogr, 11, 211–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornew L, Roberts TP, Blaskey L & Edgar JC (2012) Resting-state oscillatory activity in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord, 42, 1884–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg L, Kovacevic N, McIntosh AR, Poulsen C, Martinu K, Leonard G & Paus T (2011) Maturation of EEG power spectra in early adolescence: a longitudinal study. Dev Sci, 14, 935–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csépe V (1995) On the origin and development of the mismatch negativity. Ear Hear, 16, 91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edden RA, Muthukumaraswamy SD, Freeman TC & Singh KD (2009) Orientation discrimination performance is predicted by GABA concentration and gamma oscillation frequency in human primary visual cortex. J Neurosci, 29, 15721–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JC, Dipiero M, McBride E, Green HL, Berman J, Ku M, Liu S, Blaskey L, Kuschner E, Airey M, Ross JL, Bloy L, Kim M, Koppers S, Gaetz W, Schultz RT & Roberts TPL (2019) Abnormal maturation of the resting-state peak alpha frequency in children with autism spectrum disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JC, Fisk Iv CL, Berman JI, Chudnovskaya D, Liu S, Pandey J, Herrington JD, Port RG, Schultz RT & Roberts TP (2015a) Auditory encoding abnormalities in children with autism spectrum disorder suggest delayed development of auditory cortex. Mol Autism, 6, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JC, Khan SY, Blaskey L, Chow VY, Rey M, Gaetz W, Cannon KM, Monroe JF, Cornew L, Qasmieh S, Liu S, Welsh JP, Levy SE & Roberts TP (2015b) Neuromagnetic oscillations predict evoked-response latency delays and core language deficits in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord, 45, 395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JC, Lanza MR, Daina AB, Monroe JF, Khan SY, Blaskey L, Cannon KM, Jenkins J, Qasmieh S, Levy SE & Roberts TP (2014) Missing and delayed auditory responses in young and older children with autism spectrum disorders. Front Hum Neurosci, 8, 417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein HT (1980) EEG developmental stages. Developmental Psychology, 13, 621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JM & Hillyard SA (1981) Event-related potentials (ERPs) to interruptions of a steady rhythm. Psychophysiology, 18, 322–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz W, Bloy L, Wang DJ, Port RG, Blaskey L, Levy SE & Roberts TP (2014) GABA estimation in the brains of children on the autism spectrum: measurement precision and regional cortical variation. Neuroimage, 86, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz W, Edgar JC, Wang DJ & Roberts TP (2011) Relating MEG measured motor cortical oscillations to resting γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentration. Neuroimage, 55, 616–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage NM, Siegel B, Callen M & Roberts TP (2003a) Cortical sound processing in children with autism disorder: an MEG investigation. Neuroreport, 14, 2047–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage NM, Siegel B & Roberts TP (2003b) Cortical auditory system maturational abnormalities in children with autism disorder: an MEG investigation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res, 144, 201–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandal MJ, Edgar JC, Ehrlichman RS, Mehta M, Roberts TP & Siegel SJ (2010) Validating γ oscillations and delayed auditory responses as translational biomarkers of autism. Biol Psychiatry, 68, 1100–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs FA & Knott JR (1949) Growth of the electrical activity of the cortex. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 1, 223–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haegens S, Cousijn H, Wallis G, Harrison PJ & Nobre AC (2014) Inter- and intra-individual variability in alpha peak frequency. Neuroimage, 92, 46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handy TE 2005. Event-related potentials: A methods handbook. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hari R 1990. The neuromagnetic method in the study of the human auditory cortex In Auditory evoked magnetic fields and potentials advances in audiology., eds. G. M.H. & R. G. Basel: Karger. [Google Scholar]

- Hari R, Hämäläinen M & Joutsiniemi SL (1989) Neuromagnetic steady-state responses to auditory stimuli. J Acoust Soc Am, 86, 1033–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari R & Salmelin R (1997) Human cortical oscillations: a neuromagnetic view through the skull. Trends Neurosci, 20, 44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang MX, Huang CW, Robb A, Angeles A, Nichols SL, Baker DG, Song T, Harrington DL, Theilmann RJ, Srinivasan R, Heister D, Diwakar M, Canive JM, Edgar JC, Chen YH, Ji Z, Shen M, El-Gabalawy F, Levy M, McLay R, Webb-Murphy J, Liu TT, Drake A & Lee RR (2014) MEG source imaging method using fast L1 minimum-norm and its applications to signals with brain noise and human resting-state source amplitude images. Neuroimage, 84, 585–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR 1987. Normal limits of the EEG In A textbook of Clinical Neurophysiology, eds. Halliday RM, Butler SR & Paul R, 105–154. Wiley, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Huotilainen M, Winkler I, Alho K, Escera C, Virtanen J, Ilmoniemi RJ, Jääskeläinen IP, Pekkonen E & Näätänen R (1998) Combined mapping of human auditory EEG and MEG responses. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 108, 370–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John ER, Ahn H, Prichep L, Trepetin M, Brown D & Kaye H (1980) Developmental equations for the electroencephalogram. Science, 210, 1255–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L (1943) Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W (1999) EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: a review and analysis. Brain Research Reviews, 29, 169–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan MD, Vladutiu CJ, Schieve LA, Ghandour RM, Blumberg SJ, Zablotsky B, Perrin JM, Shattuck P, Kuhlthau KA, Harwood RL & Lu MC (2018) The prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder among US children. Pediatrics, 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus N, McGee T, Sharma A, Carrell T & Nicol T (1992) Mismatch negativity event-related potential elicited by speech stimuli. Ear Hear, 13, 158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause CM, Pesonen M & Hämäläinen H (2007) Brain oscillatory responses during the different stages of an auditory memory search task in children. Neuroreport, 18, 213–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzberg D, Vaughan HG, J. A. K Jr. & Fliegler KZ (1995) Developmental studies and clinical applications of mismatch negativity: Problems and prospects. Ear and Hearing, 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ 2005. An introduction to event-related potential technique. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lütkenhöner B & Steinsträter O (1998) High-precision neuromagnetic study of the functional organization of the human auditory cortex. Audiol Neurootol, 3, 191–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki J, Kagitani-Shimono K, Goto T, Sanefuji W, Yamamoto T, Sakai S, Uchida H, Hirata M, Mohri I, Yorifuji S & Taniike M (2012) Differential responses of primary auditory cortex in autistic spectrum disorder with auditory hypersensitivity. Neuroreport, 23, 113–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki J, Kagitani-Shimono K, Sugata H, Hanaie R, Nagatani F, Yamamoto T, Tachibana M, Tominaga K, Hirata M, Mohri I & Taniike M (2017) Delayed Mismatch Field Latencies in Autism Spectrum Disorder with Abnormal Auditory Sensitivity: A Magnetoencephalographic Study. Front Hum Neurosci, 11, 446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki J, Ku M, Berman JI, Blaskey L, Bloy L, Chen YH, Dell J, Edgar JC, Kuschner ES, Liu S, Saby J, Brodkin ES & Roberts TPL (2019a) Abnormal auditory mismatch fields in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Neurosci Lett, 698, 140–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki J, Kuschner ES, Blaskey L, Bloy L, Kim M, Ku M, Edgar JC, Embick D & Roberts TPL (2019b) Abnormal auditory mismatch fields are associated with communication impairment in both verbal and minimally verbal/nonverbal children who have autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden KL, Hepburn S, Winterrowd E, Schmidt GL & Rojas DC (2012) Abnormalities in gamma-band responses to language stimuli in first-degree relatives of children with autism spectrum disorder: an MEG study. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskovic V, Ma X, Chou CA, Fan M, Owens M, Sayama H & Gibb BE (2015) Developmental changes in spontaneous electrocortical activity and network organization from early to late childhood. Neuroimage, 118, 237–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumaraswamy SD, Edden RA, Jones DK, Swettenham JB & Singh KD (2009) Resting GABA concentration predicts peak gamma frequency and fMRI amplitude in response to visual stimulation in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 106, 8356–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä JP, Hämäläinen M, Hari R & McEvoy L (1994) Whole-head mapping of middle-latency auditory evoked magnetic fields. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 92, 414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuper C & Pfurtscheller G (2001) Event-related dynamics of cortical rhythms: frequency-specific features and functional correlates. Int J Psychophysiol, 43, 41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedermeyer E 1993a. Maturation of the EEG: development of waking and sleep patterns In Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields, eds. Niedermeyer E & da Silva F. H. Lopes, 167–191. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Niedermeyer E, 1993b. The normal EEG of the waking adult In Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields, eds. Niedermeyer E & da Silva F. H. Lopes, 167–191. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R 1992. Attention and brain function. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R, Gaillard AW & Mäntysalo S (1978) Early selective-attention effect on evoked potential reinterpreted. Acta Psychol (Amst), 42, 313–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R, Paavilainen P, Rinne T & Alho K (2007) The mismatch negativity (MMN) in basic research of central auditory processing: a review. Clin Neurophysiol, 118, 2544–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oram Cardy JE, Flagg EJ, Roberts W, Brian J & Roberts TP (2005a) Magnetoencephalography identifies rapid temporal processing deficit in autism and language impairment. Neuroreport, 16, 329–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oram Cardy JE, Flagg EJ, Roberts W & Roberts TP (2008) Auditory evoked fields predict language ability and impairment in children. Int J Psychophysiol, 68, 170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oram Cardy JE, Flagg EJ, Roberts W & Roberts TPL (2005b) Delayed mismatch field for speech and nonspeech sounds in children with autism. Neuroreport, 16, 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paetau R, Ahonen A, Salonen O & Sams M (1995) Auditory evoked magnetic fields to tones and pseudowords in healthy children and adults. J Clin Neurophysiol, 12, 177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelizzone M, Hari R, Mäkelä JP, Huttunen J, Ahlfors S & Hämäläinen M (1987) Cortical origin of middle-latency auditory evoked responses in man. Neurosci Lett, 82, 303–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen M, Björnberg CH, Hämäläinen H & Krause CM (2006) Brain oscillatory 1–30 Hz EEG ERD/ERS responses during the different stages of an auditory memory search task. Neurosci Lett, 399, 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponton CW, Eggermont JJ, Kwong B & Don M (2000) Maturation of human central auditory system activity: evidence from multi-channel evoked potentials. Clin Neurophysiol, 111, 220–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port RG, Anwar AR, Ku M, Carlson GC, Siegel SJ & Roberts TP (2015) Prospective MEG biomarkers in ASD: pre-clinical evidence and clinical promise of electrophysiological signatures. Yale J Biol Med, 88, 25–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port RG, Gaetz W, Bloy L, Wang DJ, Blaskey L, Kuschner ES, Levy SE, Brodkin ES & Roberts TPL (2017) Exploring the relationship between cortical GABA concentrations, auditory gamma-band responses and development in ASD: Evidence for an altered maturational trajectory in ASD. Autism Res, 10, 593–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port RG, Oberman LM & Roberts TP (2019) Revisiting the excitation/inhibition imbalance hypothesis of ASD through a clinical lens. Br J Radiol, 20180944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reite M, Teale P, Zimmerman J, Davis K & Whalen J (1988) Source location of a 50 msec latency auditory evoked field component. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 70, 490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TP, Cannon KM, Tavabi K, Blaskey L, Khan SY, Monroe JF, Qasmieh S, Levy SE & Edgar JC (2011) Auditory magnetic mismatch field latency: a biomarker for language impairment in autism. Biol Psychiatry, 70, 263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TP, Ferrari P, Stufflebeam SM & Poeppel D (2000) Latency of the auditory evoked neuromagnetic field components: stimulus dependence and insights toward perception. J Clin Neurophysiol, 17, 114–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TP, Heiken K, Kahn SY, Qasmieh S, Blaskey L, Solot C, Parker WA, Verma R & Edgar JC (2012) Delayed magnetic mismatch negativity field, but not auditory M100 response, in specific language impairment. Neuroreport, 23, 463–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TP, Khan SY, Rey M, Monroe JF, Cannon K, Blaskey L, Woldoff S, Qasmieh S, Gandal M, Schmidt GL, Zarnow DM, Levy SE & Edgar JC (2010) MEG detection of delayed auditory evoked responses in autism spectrum disorders: towards an imaging biomarker for autism. Autism Res, 3, 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TP, Lanza MR, Dell J, Qasmieh S, Hines K, Blaskey L, Zarnow DM, Levy SE, Edgar JC & Berman JI (2013) Maturational differences in thalamocortical white matter microstructure and auditory evoked response latencies in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res, 1537, 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TP, Matsuzaki J, Blaskey L, Bloy L, Edgar JC, Kim M, Ku M, Kuschner ES & Embick D. 2019. Delayed M50/M100 latency arising from superior temporal gyrus in minimally verbal/nonverbal children. In International Society for Autism Research. Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TP & Poeppel D (1996) Latency of auditory evoked M100 as a function of tone frequency. Neuroreport, 7, 1138–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas DC, Maharajh K, Teale P & Rogers SJ (2008) Reduced neural synchronization of gamma-band MEG oscillations in first-degree relatives of children with autism. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JL & Merzenich MM (2003) Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav, 2, 255–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmelin R & Hari R (1994) Characterization of spontaneous MEG rhythms in healthy adults. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 91, 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Shinn-Cunningham B & Tager-Flusberg H (2018) Meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature characterizing auditory mismatch negativity in individuals with autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 87, 106–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somsen RJ, van’t Klooster BJ, van der Molen MW, van Leeuwen HM & Licht R (1997) Growth spurts in brain maturation during middle childhood as indexed by EEG power spectra. Biol Psychol, 44, 187–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapells DR, Linden D, Suffield JB, Hamel G & Picton TW (1984) Human auditory steady state potentials. Ear Hear, 5, 105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroganova TA, Orekhova EV & Posikera IN (1999) EEG alpha rhythm in infants. Clin Neurophysiol, 110, 997–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigawa J, Kagitani-Shimono K, Matsuzaki J, Ogawa R, Hanaie R, Yamamoto T, Tominaga K, Nabatame S, Mohri I, Taniike M & Ozono K (2018) Atypical auditory language processing in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Clin Neurophysiol, 129, 2029–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavabi K, Embick D & Roberts TP (2011) Spectral-temporal analysis of cortical oscillations during lexical processing. Neuroreport, 22, 474–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Pipa G, Lima B, Melloni L, Neuenschwander S, Nikolić D & Singer W (2009) Neural synchrony in cortical networks: history, concept and current status. Front Integr Neurosci, 3, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XJ (2010) Neurophysiological and computational principles of cortical rhythms in cognition. Physiol Rev, 90, 1195–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TW, Rojas DC, Reite ML, Teale PD & Rogers SJ (2007) Children and adolescents with autism exhibit reduced MEG steady-state gamma responses. Biol Psychiatry, 62, 192–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich JL & Cone-Wesson BK (2006) Maturation of CAEP in infants and children: a review. Hear Res, 212, 212–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura Y, Kikuchi M, Hayashi N, Hiraishi H, Hasegawa C, Takahashi T, Oi M, Remijn GB, Ikeda T, Saito DN, Kumazaki H & Minabe Y (2017) Altered human voice processing in the frontal cortex and a developmental language delay in 3- to 5-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder. Sci Rep, 7, 17116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiura T, Ueno S, Iramina K & Masuda K (1995) Source localization of middle latency auditory evoked magnetic fields. Brain Res, 703, 139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yvert B, Crouzeix A, Bertrand O, Seither-Preisler A & Pantev C (2001) Multiple supratemporal sources of magnetic and electric auditory evoked middle latency components in humans. Cereb Cortex, 11, 411–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]