Abstract

Background

Vitamin D plays a protective role in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients through unclear mechanisms. Cathelicidin is an antimicrobial peptide induced by 1,25(OH)D2. Our goal was to evaluate the link between cathelicidin and vitamin D–associated clinical outcomes in UC patients, explore vitamin D induction of cathelicidin in human colon cells, and evaluate the effects of intrarectal human cathelicidin on a murine model of colitis.

Methods

Serum and colonic cathelicidin levels were measured in UC patients and correlated with clinical and histologic outcomes. Human colon cells were treated with 1,25(OH)2D and production of cathelicidin and cytokines were quantified. Antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli from cell culture supernatants was measured. Mice were treated with intrarectal cathelicidin, and its effects on DSS colitis and intestinal microbiota were evaluated.

Results

In UC patients, serum 25(OH)D positively correlated with serum and colonic cathelicidin. Higher serum cathelicidin is associated with decreased risk of histologic inflammation and clinical relapse but not independent of 25(OH)D or baseline inflammation. The 1,25(OH)2D treatment of colon cells induced cathelicidin and IL-10, repressed TNF-α, and suppressed Escherichia coli growth. This antimicrobial effect was attenuated with siRNA-cathelicidin transfection. Intrarectal cathelicidin reduced the severity of DSS colitis but did not mitigate the impact of colitis on microbial composition.

Conclusions

Cathelicidin plays a protective role in 25(OH)D-associated UC histologic outcomes and murine colitis. Cathelicidin is induced by vitamin D in human colonic epithelial cells and promotes antimicrobial activity against E. coli. Our study provides insights into the vitamin D–cathelicidin pathway as a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: vitamin D, cathelicidin, colonic epithelium, cytokines, ulcerative colitis

INTRODUCTION

Several observational studies have linked deficiencies in vitamin D to adverse outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1 Epidemiological studies have indicated that low vitamin D is associated with active disease, mucosal inflammation, and higher levels of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein.2 Prospective studies in patients with low serum vitamin D—or 25(OH)D—levels have established it as a risk factor for higher morbidity, health care utilization in IBD, and risk of relapse in ulcerative colitis patients.3, 4 Cumulatively, these data have informed recommendations on a minimum level of vitamin D supplementation in IBD and clinical trials of vitamin D as a therapy.5 Despite the observations of the detrimental effects of low vitamin D levels, the exact mechanisms through which adequate vitamin D protects patients from these inflammatory processes are not completely understood. The hydroxylated version of vitamin D3—or 1,25(OH)2D—is primarily associated with intestinal calcium absorption in normal physiology but can also have effects on the immune system and epithelial cells in vitro.6 Previous work has demonstrated a role for vitamin D and the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier7 and protecting against experimental colitis.8 These previous mechanistic studies have linked the VDR in regulating the gut microbiota9 in animal models and patients with inflammatory bowel disease. One previous meta-analysis10 linked polymorphisms in the VDR to susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease. Understanding the mechanisms mediating the protective role of vitamin D in IBD may lead to novel insights and therapeutic strategies to improve clinical outcomes.

Vitamin D transcriptionally regulates human cathelicidin (also known as hCAP-18 or LL-37), an 18 kDa antimicrobial peptide involved in innate immune defenses.11 The vitamin D regulation of cathelicidin is only found in humans and primates and is not evolutionarily conserved.12 Cathelicidin has a broad-spectrum activity against bacteria, enveloped viruses, and fungi and mediates its antimicrobial effects by disrupting cell membranes.13 Cathelicidin is expressed by the colonic epithelium, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages and is increased in inflamed and noninflamed mucosa in ulcerative colitis patients.14, 15 Prior studies of the murine homologue (mCRAMP) have identified a protective effect in a murine model of colitis and a reduction in the growth of colonic flora.16 In an interventional study in patients with pulmonary inflammation, vitamin D supplementation led to increased airway antimicrobial activity which was mediated through cathelicidin expression.17 Cumulatively, these data suggested a role for cathelicidin in the protective effects of vitamin D in human IBD, but these links have not previously been explored. We hypothesized that cathelicidin mediates a protective role of vitamin D in ulcerative colitis and that human colonic epithelial cells would respond to elevated levels of local vitamin D metabolites—or 1,25(OH)2D—by inducing cathelicidin production. Because adherent E. coli strains have been described as having a facilitative role in flares of UC, we also measured the impact of local cathelicidin on E. coli growth.18 Finally, we evaluated the effects of increased colonic cathelicidin via exogenous intrarectal administration in a murine model of colitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ulcerative Colitis Cohort Enrollment and Clinical Definitions

Serum and colon biopsies (from the most inflamed segments) were obtained from a cohort of 70 ulcerative colitis patients in clinical remission. As described in our previous study,3 our inclusion criteria were diagnosis of ulcerative colitis, age 18 years or older, clinical remission (defined as a Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index [SCCAI] of 2 or less), recent surveillance colonoscopy with segmental biopsies, and patients who had available serum collected at time of colonoscopy. We excluded pediatric patients (age younger than 18 years old), patients with Crohn’s disease or indeterminate colitis, ulcerative colitis patients with colectomy, and ulcerative colitis patients in clinical relapse (SCCAI greater than 2). The study was approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, creatinine level, duration of disease, extent of disease, relevant medications (current nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, current mesalamine, current 6-mercaptopurine/azathioprine, current anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), steroids in the past year, and vitamin D supplementation), and season of enrollment were recorded for each patient. Baseline laboratory values (white blood cell count, hematocrit level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein level) were obtained. We did not assess for baseline dietary vitamin D intake or initiation of vitamin D supplementation during the follow-up period; we did not actively supplement patients with vitamin D based on baseline levels. In our study, we defined endoscopic inflammation as a Mayo endoscopic score of 2 or greater. Histologic inflammation was defined as a Geboes histologic score of 3 or greater. Clinical relapse during the follow-up period was defined as a SCCAI score greater than 2, medication intensification, or UC-related hospitalization at any time during our follow-up period of 12 months. Medication intensification was defined by an increase in dose of the current regimen, addition of another medication, or change in class of medication as a result of symptom relapse.

Cathelicidin Measurement and Correlation With Vitamin D in Ulcerative Colitis Patients

Serum vitamin D levels were measured by using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Calbiotech, San Diego, CA) according the manufacturer’s instructions. Cathelicidin protein concentrations in serum were measured using a commercially available ELISA kit (Hycult Biotech Inc., Plymouth Meeting, PA). Colon biopsies were lysed, total RNA was extracted, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to measure cathelicidin mRNA levels. Gene expression was normalized to the β-actin housekeeping gene using the 2-ΔΔCT method. We used univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses to calculate Pearson r coefficient and β-coefficient and to determine the correlation between serum 25(OH)D with serum cathelicidin and serum 25(OH)D with colonic cathelicidin mRNA expression. For our multivariate analysis, model building was based on forward stepwise logistic regression, with a P value of 0.05 required for entry. Correction for multiple testing was included.

Correlation of Serum Cathelicidin With Vitamin D–associated UC Clinical Outcomes

We used receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analyses to determine serum cathelicidin cut-off values most associated with histologic inflammation and clinical relapse. Using the ROC curve cut-off values for serum cathelicidin, we dichotomized the UC patient cohort into high and low serum cathelicidin groups. We used a 25(OH)D cut-off value of 35 ng/mL as described in our previous study.3 We then performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses for the outcomes of presence of histologic inflammation and future risk of clinical relapse. All variables were analyzed initially in a univariate fashion to determine their association with our UC clinical outcomes. For our multivariate analysis, model building was based on forward stepwise logistic regression, with a P value of 0.05 required for entry. We performed formal mediation analyses using the Sobel-Goodman test19 to determine the effect of serum cathelicidin as a mediator variable in the association between 25(OH)D and UC histological inflammation and between 25(OH)D and UC clinical relapse. All figures were generated using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA). Dichotomous variables were analyzed for outcomes using χ 2 test or Fisher exact test where appropriate, and continuous variables were analyzed using t test if normally distributed or Wilcoxon test for non-normal data. Correction for multiple testing was included. Calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.01; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Vitamin D cathelicidin Human Colonic Epithelial Cell (DLD1) Culture Experiments

Primary human colonic epithelial cells (DLD1) in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) growth media with 10% Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin were plated onto 6-well plates (1.0 × 106 DLD1 cells/well) and grown to 75% confluence. The DLD1 cell cultures were treated with 1,25(OH)2D (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 0 nM, 0.01 nM, 0.1 nM, 1 nM, and 10 nM (performed under dark conditions) and after 6 hours, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 100 ng/mL or control media was added to DLD1 cell cultures and incubated for another 18 hours. After 24 hours from 1,25(OH)2D treatment, cell culture supernatants and cell pellets were harvested for cathelicidin protein and mRNA measurements. Experiments were performed in triplicates. Cathelicidin protein concentrations in supernatants were measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Hycult Biotech Inc., Plymouth Meeting, PA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell pellets from DLD1 cell cultures were lysed with RIPA buffer (150 Mm NaCl, 5 Mm EDTA Ph 8.0, 50 Mm Tris pH 8.0, 1.0% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS); total RNA was extracted from DLD1 cell lysates using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified with a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Walmington, DE). A 260:280 ratio was evaluated to examine the quality of RNA. Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed to measure cathelicidin mRNA expression. In brief, cDNA was directly synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was diluted with nuclease-free water and used for subsequent RT-PCR using SYBR Green methodology (Bio-Rad). Each gene was amplified individually using the StepOnePlus Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Melting curve analysis was performed every time to confirm that amplification was derived from a single peak. The cycle threshold (Ct) was determined by the analytical software, StepOne Software version 2.3 (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of the cathelicidin (CAMP) primers used in the PCR reaction were Forward 5’-3’-CCAGGACGACACAGCAGTCA and Reverse-5’-3’CTTCACCAGCCCGTCCTTC. Gene expression was normalized to the β-actin housekeeping gene using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

Vitamin D-Cytokine Human Colonic Epithelial Cell (DLD1) Cell Culture Experiments

Primary human colonic epithelial cells (DLD1) in RPMI media with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin were plated onto 6-well plates (1.0 × 106 DLD1 cells/well) and grown to 75% confluence. The DLD1 cell cultures were treated with 1,25(OH)2D (Sigma-Aldrich) at 0 nM, 10 nM, 50 nM, and 100 nM (performed under dark conditions) and incubated for 24 hours. After 24 hours, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 100 ng/mL or control media was added to DLD1 cell cultures and incubated for another 24 hours. After 48 hours from 1,25(OH)2D treatment, cell culture supernatants and cell pellets were harvested for cytokine protein and mRNA measurements. Experiments were performed in triplicates. A magnetic bead-based multiplex human cytokine assay (Milliplex, MAP Kit; EMD Millipore Corporation, St. Charles, MI) was used to measure cytokine protein concentrations according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cytokines (interleukin [IL]-10 and TNF-α) that were found to be altered at the protein level with 1,25(OH)2D treatment in DLD1 cell culture experiments were further assessed for mRNA analysis using real time quantitative PCR. Cell pellets from DLD1 cell cultures were lysed with RIPA buffer. Total RNA was extracted from DLD1 cell lysates using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed to measure IL-10 and TNF-α mRNA expression according to manufacturer’s instructions as previously described. Sequences of the human primers used for PCR amplification are as follows: IL-10 (forward 5’-3’: GGTTGCCAAGCCTTGTCTGA, reverse 5’-3’: AGGGAGTTCACATGCGCCT) and TNF-α (forward 5’-3’: GGAGAAGGGTGACCGACTCA, reverse 5’-3’: CTGCCCAGACTCGGCAA). Gene expression was normalized to the β-actin housekeeping gene using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

In vitro E. coli Antimicrobial Assays

Escherichia coli (strain HB10 K12, BioRad, Hercules, CA) was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth for 48 hours. The E. coli cell concentration (cells/mL) was determined by measuring the optical density (spectrophotometer at λ = 600 nm). Then 100 uL of DLD1 colon cell culture supernatants at 0 nM or 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D+ LPS from our previous experiments were incubated with 50 uL of E. coli (5.0 × 106 cells) for 24 hours. The resulting mixture was diluted 1:107 with LB media, and 50 uL of this mixture were plated onto agar plates and grown for 24 hours. The number of colony forming units (CFUs) was then counted.

siRNA Experiments

Primary human colonic epithelial cells in RPMI media with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin were plated onto 6-well plates (2.5 × 105 DLD1 cells/well) and grown to 75% confluence. The DLD1 colon cell cultures were then transfected using siPORT NeoFX reagent and siRNA specific to cathelicidin (CAMP) or siRNA nonspecific controls (2 μM) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Ambion AM 1640, Foster City, CA). The transfected cell cultures were grown for 24 hours and then treated with 1,25(OH)2D at 0 nM or 10 nM (performed under dark conditions); after 6 hours, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 100 ng/mL or control media was added to DLD1 cell cultures and incubated for another 18 hours. After 24 hours from 1,25(OH)2D treatment, cell culture supernatants and cell pellets were harvested, and cathelicidin protein and mRNA levels were measured as previously described. Supernatants from DLD1 cells transfected with siRNA followed by 0 nM or 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D3+ LPS treatment were then used to perform E. coli antimicrobial assays as previously described.

Intrarectal Mice Treatment Experiments

The experimental protocol was approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under protocol 068–2015. Male C57BL/6J mice (8 weeks old) were used throughout the experiment. Baseline fecal pellets were collected from ten C57BL/6J mice and stored in −80°C freezer until further processing. From this group, 5 mice (control group) were given daily intrarectal (IR) injections with 100 μL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS), and the other 5 mice (experimental group) were given daily intrarectal (IR) injections of 100 μL cathelicidin (LL37) (AnaSpec Inc., Fremont, CA) at 5 mg/kg. Mice were kept in an inverted position for approximately 1 minute to prevent leakage of contents from the rectum. Mice weights, stool consistency, and presence of macroscopic fecal blood were recorded daily. After 7 consecutive days of IR injections, fecal samples were collected and stored.

Dextran Sodium Sulfate–induced Murine Colitis Experiments

After 7 days of IR treatment, experimental colitis was induced in the same mice by administering 3% (weight/volume) dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in drinking water. Along with daily 3% DSS treatment, the same 5 mice in each of the control and experimental groups mice received parallel IR treatments with PBS or LL37, respectively. Mice weights, stool consistency, and presence of macroscopic fecal blood were recorded daily. After 7 days of treatment with 3% DSS and intrarectal PBS or LL37, fecal samples were collected, and mice were euthanized for histologic analysis.

Disease Activity Index Assessment

Disease activity index was scored throughout the DSS experiment using the combined clinical parameters of weight loss, stool consistency, and fecal bleeding as previously described.20 For fecal bleeding, only macroscopic bleeding was assessed (2 points for slight bleeding defined as small streaks of blood or presence of melena or 4 points for gross rectal bleeding or bloody diarrhea).

Morphologic Assessment and Histologic Inflammation Scoring

After mice were euthanized, colon and spleen were harvested in a sterile fashion. Colon lengths and spleen weights were measured. The distal third of the colon segments were used for histologic analysis. Colon segments were cut longitudinally and fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution (pH 7.4), processed for paraffin embedding, and cut into 5-μm-thick sections. Hematoxylin-eosin staining was performed for histologic examination. Histologic inflammation was graded microscopically by a pathologist (GM) blinded to treatment allocation. Severity of colitis was graded based on inflammatory cell infiltration and intestinal architecture/epithelial damage as previously described.21 Final histologic inflammation scores were based on the highest score for each colonic segment assessed.

Fecal Gut Microbiome Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analyses

Fecal samples were shipped to a commercial provider (Idexx, Fremont, CA) where library generation and sequencing were performed (Microbiome Insights, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). DNA was extracted from fecal pellets using the Qiagen MagAttract PowerSoil DNA KF Kit following the manufacturer’s recommendations, with an additional bead-beating step to increase mechanical disruption. Samples were stored at −80°C until sequencing. DNA quantification and quality checks were done via Qubit (New York, NY). Phusion polymerase was used for amplification of marker genes. Polymerase chain reaction was done with primers targeting the prokaryotic (16S V4, V1-V3) regions. The PCR reactions were cleaned up and normalized using the high-throughput SequalPrep 96-well Plate Kit. Samples were then pooled to make 1 library that was quantified accurately with the KAPA qPCR Library Quant kit. Library pools were sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq using the corresponding primer sets for either prokaryotic (16S V4, V1-V3) regions.

Retrieved sequences were demultiplexed in QIIME v1.9 and then trimmed, clipped, and quality-filtered using the Fastx Toolkit (hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit) to 245 bp with a minimum quality threshold of Q19. Filtered R1 reads were processed into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using minimum entropy decomposition (MED). Taxonomy was then assigned to the representative sequence for each MED node by using QIIME. Groups were compared using the Pearson χ 2 test or Fisher exact test for qualitative variables and the Student t test or the Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative variables. Gut microbiota α-Diversity was quantified using a measure of richness (Chao1 index) and a measure of evenness (Simpson’s diversity index = 1 − Simpson’s index), whereas β-diversity was quantified using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index. Tests of differences in α-diversity between samples were performed using nonparametric multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). P values were corrected according to the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

Values for relative abundance of OTUs in each client were compiled into Microsoft Excel v16.25. The data were then loaded into PAST v3.25 (http://folk.uio.no/ohammer/past). Graphical analysis of relative abundance of OTUs in individual clients was completed using PAST. From the graphical analysis generated by PAST, specific bacterial strains were pinpointed, and trends were more closely observed using Excel. Graphs of individual OTU abundance across all groups were generated using Excel. Groups were compared using the t test to calculate values of P in Excel. Values of P less than 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. Diversity of OTU abundance in each individual was done by calculating the Shannon Index for each client (Shannon Index diversity = - Σ i = 1S [pi * ln(pi)], with pi representing the proportion of the population made up of species i and S being the number of species in the sample). A graph displaying the Shannon Index for each group was generated using PAST.

RESULTS

25(OH)D Is an Independent Predictor of Serum and Colonic Cathelicidin in Ulcerative Colitis Patients in Remission

Supplementary Figure 1 summarizes the baseline clinical characteristics of the 70 ulcerative colitis patients in clinical remission included in this study as previously published.3Figure 1 summarizes the association of cathelicidin with 25(OH)D and clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis patients. In a cohort of ulcerative colitis patients in remission, higher serum 25(OH)D levels are associated with higher serum cathelicidin protein levels (Figure 1A, Pearson r 0.4138; P < 0.001). Among UC patients, a serum 25(OH)D level >20 ng/mL was associated with a 10.6-fold increase in cathelicidin mRNA expression compared with UC patients with a 25(OH)D level ≤20 ng/mL (P < 0.01; Figure 1B). Table 1 summarizes the clinical factors associated with serum cathelicidin levels and fold expression of colonic cathelicidin mRNA in ulcerative colitis patients. In univariate analysis, 25(OH)D positively correlated with serum cathelicidin levels (β = 1.23; P < 0.01), whereas histologic inflammation negatively correlated with serum cathelicidin levels (β = −59.51; P = 0.003). In multivariate analysis, only 25(OH)D positively correlated with serum cathelicidin levels (β = 0.90; P = 0.018). In univariate analysis, 25(OH)D levels positively correlated with colonic cathelicidin mRNA expression (β = 1.028 × 10–4; P = 0.016). In multivariate analysis, 25(OH)D positively correlated with colonic mRNA expression (β=9.60 × 10–5; P = 0.035), whereas histologic inflammation negatively correlated with colonic mRNA expression (β = −4.42 × 10–3; P = 0.046).

FIGURE 1.

Summarizes the association of cathelicidin with vitamin D and clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis patients. A, Higher serum 25(OH)D levels is associated with higher serum cathelicidin protein levels (Pearson r = 0.4138; P < 0.001) .B, Serum 25(OH)D level >20 ng/mL is associated with a 10.6-fold increase in cathelicidin mRNA expression compared with UC patients with a 25(OH)D level ≤20 ng/mL (P < 0.01). C, Serum cathelicidin levels are higher in UC patients with histologic mucosal healing compared with UC patients with histologic inflammation (245.2 ng/mL vs 196.5 ng/mL; P < 0.01). Serum cathelicidin levels are higher in UC patients who remained in clinical remission compared with UC patients who had a clinical relapse at 1-year follow-up (238.0 ng/mL vs 195.1 ng/mL; 0.01). D, The area under the curve (AUC) for serum cathelicidin in detecting the presence of histologic inflammation was 0.70 (P < 0.01). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Factors Associated with Serum Cathelicidin Levels and Colonic Cathelicidin mRNA Expression in Ulcerative Colitis Patients

| Serum Cathelicidin | Colonic Cathelicidin mRNAa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| Clinical Variables | β-Coefficient | P | β-Coefficient | P | β-Coefficient | P Value | β-Coefficient | P |

| Age (per year) | −0.08 | 0.904 | −3.227E-05 | 0.521 | ||||

| Female Gender | 36.59 | 0.087 | 2.423E-03 | 0.171 | ||||

| Caucasian Ethnicity | −24.13 | 0.286 | −3.890E-04 | 0.858 | ||||

| Smoking (Current) | 51.76 | 0.400 | 8.666E-05 | 0.983 | ||||

| Season of enrollment (low sunlight)b | −16.51 | 0.424 | −1.431E-03 | 0.419 | ||||

| Serum Vitamin D level (per 1 ng/mL) | 1.23 | <0.001 | 0.90 | 0.018 | 1.028E-04 | 0.016 | 9.602E-05 | 0.035 |

| Current Vitamin D Supplementation | 27.27 | 0.194 | 1.623E-03 | 0.365 | ||||

| Current NSAIDs | −23.65 | 0.489 | 4.237E-04 | 0.848 | ||||

| Current 5ASA | −21.20 | 0.375 | 8.039E-04 | 0.683 | ||||

| Current 6MP/AZA | 11.96 | 0.641 | −1.921E-03 | 0.486 | ||||

| Current anti-TNF-α | −44.77 | 0.310 | −3.024E-03 | 0.540 | ||||

| Steroids in past year | −21.41 | 0.507 | −1.295E-03 | 0.619 | ||||

| Endoscopic Inflammationc | −57.43 | 0.057 | −6.44 | 0.841 | −2.242E-03 | 0.484 | ||

| Histologic Inflammationd | −59.51 | 0.003 | −41.09 | 0.067 | −3.292E-03 | 0.070 | -4.442E-03 | 0.046 |

aRelative cathelicidin mRNA expression normalized to β-actin housekeeping gene

bLow sunlight season in Massachusetts is September to February, high sunlight season is from March to August

cEndoscopic inflammation defined by Mayo Endoscopic Score ≥2

dHistologic inflammation defined by Geboes Histologic Grade ≥3

Serum Cathelicidin Correlates With Histologic Inflammation and Future Clinical Relapse in Ulcerative Colitis But Not Independent of 25(OH)D and Baseline Histologic Inflammation

Serum cathelicidin levels were higher in UC patients with histologic mucosal healing compared with UC patients with histologic inflammation (245.2 ng/mL vs 196.5 ng/mL; P < 0.01). Likewise, serum cathelicidin levels were higher in UC patients who remained in clinical remission compared with UC patients who had a clinical relapse at 1-year follow-up (238.0 ng/mL vs 195.1 ng/mL; P < 0.01; Figure 1C). The area under the curve (AUC) for serum cathelicidin in detecting the presence of histologic inflammation was 0.70 (P < 0.01; Figure 1D). Table 2 summarizes the clinical factors associated with presence of histologic inflammation in ulcerative colitis patients in remission. In univariate analysis, 25(OH)D ≤35 ng/mL (odds ratio [OR] 1.63; 95% CI, 1.46–1.82; P < 0.0001) and endoscopic inflammation (OR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.57–2.18; P < 0.001) were associated with increased histologic inflammation, whereas a serum cathelicidin >201.5 ng/mL was associated with decreased histologic inflammation (OR 0.70; 95% CI, 0.62–0.79; P = 0.004). In multivariate analysis, only 25(OH)D ≤35 ng/mL was independently associated with increased histologic inflammation (OR 1.40; 95% CI, 1.24–1.57; P = 0.006). The association of serum cathelicidin with histologic inflammation was no longer statistically significant (P = 0.115) in multivariate analysis when adjusting for 25(OH)D levels. Table 3 summarizes the clinical factors associated with risk of future clinical relapse in 12 months among UC patients in remission. In univariate analysis, 25(OH)D ≤35 ng/mL (OR 1.26; 95% CI, 1.16–1.71; P = 0.001), steroids in the past year (OR 1.46; 95% CI, 1.05–2.04; P = 0.026), and baseline histologic inflammation (OR 1.52; 95% CI, 1.22–1.89; P < 0.001) were associated with increased risk of future clinical relapse, whereas a serum cathelicidin >201.5 ng/mL was associated with decreased risk of clinical relapse (OR 0.79; 95% CI, 0.63–0.99; P = 0.045). In multivariate analysis, only baseline histologic inflammation was independently associated with increased risk of clinical relapse (OR 1.29; 95% CI, 1.03–1.62; P = 0.029). The association of 25(OH)D with clinical relapse was no longer significant (P = 0.134) after adjusting cathelicidin levels in multivariate analysis. Serum cathelicidin was found to have a statistically significant effect as a mediator variable in the association between 25(OH)D and UC histologic mucosal healing (Sobel-Goodman test, P = 0.02). There was a trend toward significance in serum cathelicidin as a mediator variable in the association between 25(OH)D and UC clinical relapse (Sobel-Goodman test, P = 0.06).

TABLE 2.

Clinical Factors Associated With Presence of Histologic Inflammationa Among Ulcerative Colitis Patients in Remission

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | ||

| Age (per year) | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.072 | ||||

| Female Gender | 1.00 | 0.88 | 1.13 | 0.989 | ||||

| Caucasian Ethnicity | 1.30 | 1.15 | 1.49 | 0.044 | 1.07 | 0.94 | 1.20 | 0.599 |

| Smoking (Current) | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.89 | 0.193 | ||||

| Season of enrollment (low sunlight)b | 1.11 | 0.99 | 1.25 | 0.384 | ||||

| Serum Vitamin D ≤ 35 ng/mL | 1.63 | 1.46 | 1.82 | <.0001 | 1.40 | 1.24 | 1.57 | 0.006 |

| Serum Cathelicidin > 201.5 ng/mL | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 0.004 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.93 | 0.115 |

| Current Vitamin D Supplementation | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.96 | 0.196 | ||||

| Current NSAIDs | 1.14 | 0.93 | 1.39 | 0.529 | ||||

| Current 5ASA | 1.24 | 1.08 | 1.42 | 0.125 | ||||

| Current 6MP/AZA | 1.15 | 0.99 | 1.34 | 0.344 | ||||

| Current anti-TNF-α | 0.80 | 0.62 | 1.04 | 0.399 | ||||

| Steroids in past year | 1.39 | 1.16 | 1.68 | 0.079 | ||||

| Endoscopic Inflammationc | 1.85 | 1.57 | 2.18 | <.001 | 1.40 | 1.18 | 1.66 | 0.053 |

aHistologic inflammation defined as Geboes score ≥3

bLow sunlight season in Massachusetts is September to February, high sunlight season is from March to August

cEndoscopic inflammation defined by Mayo Endoscopic Score ≥ 2

TABLE 3.

Clinical Factors Associated With Clinical Relapse at 12 Months in Ulcerative Colitis Patients in Remission

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | ||

| Age (per year) | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.146 | ||||

| Female Gender | 1.06 | 0.84 | 1.34 | 0.601 | ||||

| Caucasian Ethnicity | 1.15 | 0.90 | 1.46 | 0.257 | ||||

| Smoking (Current) | 1.24 | 0.64 | 2.40 | 0.513 | ||||

| Season of enrollment (low sunlight)a | 1.20 | 0.97 | 3.32 | 0.097 | ||||

| Serum Vitamin D ≤35 ng/mL | 1.26 | 1.16 | 1.75 | 0.001 | 1.19 | 0.95 | 1.50 | 0.134 |

| Serum Cathelicidin >201.5 ng/mL | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.99 | 0.045 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 1.15 | 0.451 |

| Current Vitamin D Supplementation | 0.87 | 0.70 | 1.09 | 0.220 | ||||

| Current NSAIDs | 1.00 | 0.69 | 1.44 | 0.980 | ||||

| Current 5ASA | 1.26 | 0.98 | 1.61 | 0.073 | ||||

| Current 6MP/AZA | 1.12 | 0.85 | 1.49 | 0.411 | ||||

| Current anti-TNF-α | 0.96 | 0.60 | 1.54 | 0.859 | ||||

| Steroids in past year | 1.46 | 1.05 | 2.04 | 0.026 | 1.25 | 0.91 | 1.71 | 0.164 |

| Endoscopic Inflammationb | 1.35 | 0.98 | 1.87 | 0.066 | ||||

| Histologic Inflammationc | 1.52 | 1.22 | 1.89 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 1.03 | 1.62 | 0.029 |

aLow sunlight season in Massachusetts is September to February, high sunlight season is from March to August

bEndoscopic inflammation defined by Mayo Endoscopic Score ≥2

cHistologic inflammation defined by Geboes Histologic Grade ≥3

Treatment of Colonic Epithelial Cells With 1,25(OH)2D Produces Cathelicidin and an Anti-inflammatory Cytokine Response

Figure 2A summarizes the effect of 1,25(OH)D2 on cathelicidin mRNA expression by DLD1 colonic epithelial cells. Treatment of DLD1 colonic epithelial cells with 1,25(OH)2D increased cathelicidin mRNA expression by 3.46-fold (P < 0.01) and 3.04-fold (P < 0.01) at 0.01 nM and 0.1 nM, respectively, compared with controls. The 1,25(OH)2D alone at 1 nM and 10 nM did not result in expression of cathelicidin mRNA compared with controls. Because previous studies22 have shown that LPS stimulates expression of cathelicidin, we investigated whether 1,25(OH)2D induction of cathelicidin may be enhanced by the presence of a microbial stimulus such as LPS. Treatment of LPS (at 100 ng/mL) alone did not induce cathelicidin expression. Treatment of 1,25(OH)2D with LPS resulted in 6.25-fold (P < 0.001) and 3.46-fold (P < 0.01) expression of cathelicidin at 0.01 nM and 0.1 nM, respectively, compared with controls. The 1,25(OH)2D treatment at 1 nM and 10 nM in the presence of LPS resulted in 2.53-fold (P < 0.05) and 2.36-fold (P < 0.05) cathelicidin expression, respectively, compared with controls. Figure 2B summarizes the effect of 1,25(OH)D2 treatment of DLD1 cells on secreted cathelicidin protein concentrations measured in cell culture supernatants. Treatment of 1,25(OH)D2 at lower concentrations (0 nM, 0.01 nM, 0.1 nM, 1 nM) with or without LPS did not increase cathelicidin protein concentrations measured from cell culture supernatants compared with controls. At 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D2 without LPS, cathelicidin protein concentration increased to 701.7 pg/mL (P < 0.01) vs 540.3 pg/mL from controls. At 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D2 with LPS, cathelicidin protein concentration increased to 735 pg/mL (P < 0.001) vs 530 pg/mL from controls. At 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D2, there was no difference in cathelicidin protein concentration between the LPS and non-LPS treatment groups. Supplementary Figure 1 summarizes the effect of 1,25(OH)D treatment on IL-10 and TNF-α mRNA and protein levels in DLD1 colon cell cultures. In the absence of LPS, 1,25(OH)2D induced IL-10 mRNA 4.75-fold (P < 0.01) and 6.07-fold (P < 0.001) at 50 nM and 100 nM, respectively. In the presence of LPS, 1,25(OH)2D induced IL-10 mRNA 9.41-fold, 10.02-fold, and 8.61-fold at 10 nM, 50, nM, and 100 nM, respectively. In the absence of LPS, 1,25(OH)2D repressed TNF-α mRNA 0.36-fold and 0.25-fold at 50 nM (P < 0.001) and 100 nM (P < 0.001), respectively. There was no effect at 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D. In the presence of LPS, 1,25(OH)2D repressed TNF-α mRNA 0.44-fold, 0.36-fold, and 0.34-fold at 10 nM, 50 nM, and 100 nM, respectively. In the absence of LPS, 1,25(OH)2D increased IL-10 protein concentrations to 9762 pg/mL (P < 0.05) and 11,445 pg/mL (P < 0.01) at 50 nM and 100 nM, respectively compared with control at 0 nM (baseline 6977 pg/mL). There was no significant change in IL-10 levels with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D. In the presence of LPS, IL-10 protein levels increased to 11,645 pg/mL (P < 0.01), 12,014 pg/mL (P < 0.01), and 10,885 pg/mL (P < 0.01) at 10 nM, 50 nM, and 100 nM, respectively, compared with controls at 0 nM of 1,25(OH)2D (baseline 7742 pg/mL). In the absence of LPS, 1,25(OH)2D decreased TNF-α protein levels to 15.5 pg/mL (P < 0.01) and 16.9 pg/mL (P < 0.01) at 50 nM and 100 nM, respectively, compared with control at 0 nM (baseline 27.9 pg/mL). There was no significant change in TNF-α protein levels with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D. In the presence of LPS, 1,25(OH)2D decreased TNF-α protein levels to 20.9 pg/mL (P < 0.05), 21.8 pg/mL(P < 0.05), and 20.7 pg/mL (P < 0.05) at 10 nM, 50 nM, and 100 nM, respectively compared with control at 0 nM (baseline 27.8 pg/mL).

FIGURE 2.

Summarizes the effect of 1,25(OH)D2 on cathelicidin mRNA and protein levels by DLD1 colonic epithelial cells. A, In the absence of LPS, 1,25(OH)2D induced cathelicidin mRNA 3.46-fold (P < 0.01) and 3.04-fold (P < 0.01) at 0.01 nM and 0.1 nM, respectively, compared with controls. In the presence of LPS, 1,25(OH)2D induced cathelicidin mRNA 6.25-fold (P < 0.01), 3.46-fold (P < 0.01), 2.53-fold (P < 0.05), and 2.36-fold (P < 0.05) at 0.01 nM, 0.1 nM, 1 nM, and 10 nM, respectively, compared with controls. B, Treatment of 1,25(OH)D2 at lower concentrations (0 nM, 0.01 nM, 0.1 nM, 1 nM) with or without LPS did not increase cathelicidin protein concentrations measured from cell culture supernatants compared with controls. At 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D2 without LPS, cathelicidin protein concentration increased to 701.7 pg/mL (P < 0.01) vs 540.3 pg/mL from controls. At 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D2 with LPS, cathelicidin protein concentration increased to 735 pg/mL (P < 0.001) vs 530 pg/mL from controls. At 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D2, there was no difference in cathelicidin protein concentration between the LPS and non-LPS treatment groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

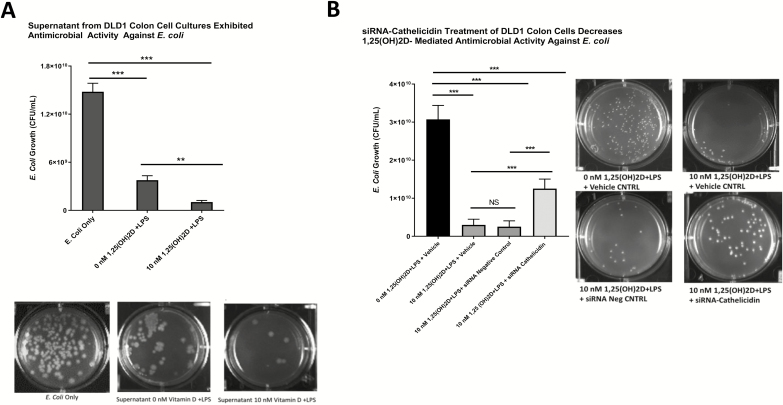

Supernatants from 1,25(OH)2D-treated Colonic Epithelial Cells Have Antimicrobial Activity Against E. Coli

Figure 3A summarizes the antimicrobial effect of supernatants from 1,25(OH)2D-treated DLD1 colonic epithelial cell cultures on E. coli. Treatment of E. coli with supernatants from DLD1 cell cultures pretreated with 0 nM of 1,25(OH)D and LPS (supernatant cathelicidin concentration 530 pg/mL) resulted in 4-fold decrease in E. coli growth (1.48 × 1010 CFU/mL vs 3.77 × 109 CFU/mL; P < 0.001). Treatment of E. coli with supernatants from DLD1 cell cultures pretreated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D and LPS (supernatant cathelicidin concentration 735 pg/mL) resulted in 14.4-fold decrease in E. coli growth (1.48 × 1010 CFU/mL vs 1.03 × 109 CFU/m; P < 0.001). Supernatants from DLD1 cell cultures pretreated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D suppressed E. coli growth 3.7-fold more (P < 0.01).

FIGURE 3.

A, Summarizes the antimicrobial effect of supernatants from 1,25(OH)2D-treated DLD1 colonic epithelial cell cultures on E. coli. Treatment of E. coli with supernatants from DLD1 cell cultures pretreated with 0 nM of 1,25(OH)D and LPS (supernatant cathelicidin concentration 530 pg/mL) resulted in 4-fold decrease in E. coli growth (1.48 × 1010 CFU/mL vs 3.77 × 109 CFU/mL; P < 0.001). Treatment of E. coli with supernatants from DLD1 cell cultures pretreated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D and LPS (supernatant cathelicidin concentration 735 pg/mL) resulted in 14.4-fold decrease in E. coli growth (1.48 × 1010 CFU/mL vs 1.03 × 109 CFU/mL; P < 0.001). Supernatants from DLD1 cell cultures pretreated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)D suppressed E. coli growth 3.7-fold more (P < 0.01). B, Summarizes the effect of siRNA-cathelicidin treatment on antimicrobial activity of supernatants from DLD1 cell cultures. Supernatants from cell cultures treated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D+ LPS + vehicle (transfection reagent) resulted in a 10.2-fold decrease in E. coli growth (3.07 × 1010 CFU/mL vs 3.0 × 109 CFU/mL; P < 0.001) compared with controls. Supernatants from cell cultures treated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D+ LPS + siRNA negative control resulted in a 12.3-fold decrease in E. coli growth (3.07 × 1010 CFU/mL vs 2.5 × 109 CFU/mL; P < 0.001) compared with controls. Supernatants from cell cultures treated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D+ LPS + siRNA-cathelicidin resulted in a 2.5-fold decrease in E. coli growth (3.07 × 1010 CFU/mL vs 1.25 × 1010 CFU/mL; P < 0.001) compared with controls. Transfection of DLD1 cells with siRNA-cathelicidin attenuated the vitamin D-induced antimicrobial activity against E. coli compared with siRNA negative controls (2.5-fold decrease vs 12.3-fold decrease in E. coli growth; P < 0.001). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Antimicrobial Effect of 1,25(OH)2D Treatment of Colonic Epithelial Cells on E. Coli Is Attenuated in the Presence of siRNA Against Cathelicidin

The DLD1 colonic epithelial cells transfected with siRNA specific to cathelicidin (siRNA-cathelicidin) and subsequently treated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D and LPS reduced cathelicidin mRNA and protein levels compared with controls (Supplementary Figure 2). Figure 3B summarizes the effect of siRNA-cathelicidin treatment on antimicrobial activity of supernatants from DLD1 cell cultures. Supernatants from cell cultures treated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D+ LPS + vehicle (transfection reagent) resulted in a 10.2-fold decrease in E. coli growth (3.07 x 1010 CFU/mL vs 3.0 x 109 CFU/mL; P < 0.001) compared with controls. Supernatants from cell cultures treated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D+ LPS + siRNA negative control resulted in a 12.3-fold decrease in E. coli growth (3.07 x 1010 CFU/mL vs 2.5 x 109 CFU/mL; P < 0.001) compared with controls. Supernatants from cell cultures treated with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D+ LPS + siRNA-cathelicidin resulted in a 2.5-fold decrease in E. coli growth (3.07 x 1010 CFU/mL vs 1.25 x 1010 CFU/mL; P < 0.001) compared with controls. Transfection of DLD1 cells with siRNA-cathelicidin attenuated the vitamin D–induced antimicrobial activity against E. coli compared with siRNA negative controls (2.5-fold decrease vs 12.3-fold decrease in E. coli growth; P < 0.001).

Administration of Cathelicidin Reduces Colitis Severity in DSS Colitis Model

Figure 4A summarizes the treatment allocation (intrarectal cathelicidin or PBS) and timeline of DSS colitis experiments. Figure 4B summarizes the effect of intrarectal cathelicidin treatment (7 days pretreatment followed by 7 days concurrent treatment with 3% DSS) on the severity of DSS colitis in wild type mice. After 7 days of 3% DSS, mice treated with cathelicidin had lower disease activity index scores compared with PBS controls (5.8 vs 10.2; P < 0.01 by Mann-Whitney U test). Similarly, mice treated with cathelicidin had lower histologic inflammation scores (Fig. 4C) compared with PBS controls (2.8 vs 5.8; P < 0.05). There was no difference in colon length between cathelicidin-treated and PBS control groups (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Mice treated with cathelicidin had lower spleen weight index (mg/g body weight) compared with PBS controls (3.49 vs 4.86; P < 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. 3B). There was a nonsignificant increase in weight loss in PBS group compared with cathelicidin-treated group: −8.9% vs −7.3%, P = 0.619 (Supplementary Fig. 3C). Compared with cathelicidin-treated mice, PBS controls had a decreased time to macroscopic fecal bleeding (P = 0.05 by Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon Test; Supplementary Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 4.

A, Summarizes the treatment allocation (IR cathelicidin or PBS) and timeline of DSS colitis experiments. B, summarizes the effect of intrarectal cathelicidin treatment on DSS colitis disease activity index. After 7 days of 3% DSS, mice treated with cathelicidin had lower disease activity index scores compared with PBS controls (5.8 vs 10.2; P < 0.01 by Mann Whitney U test) Figure 4C summarizes the effect of intrarectal cathelicidin treatment on DSS colitis histologic inflammation scores. Mice treated with cathelicidin had lower histologic inflammation scores (Figure 3C) compared with PBS controls (2.8 vs 5.8; P < 0.05). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Administration of Cathelicidin Did Not Impact DSS Colitis-induced Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis

To determine the global effects of cathelicidin on microbial communities, we undertook 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal pellets from days 0, 7, and 15 after DSS introduction in PBS and cathelicidin-treated mice. The overall baseline community composition was similar in both groups before and at day 7 and day 15 of treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Phyla diversity, as measured by the Shannon Index, increased significantly between day 0 and day 15 in both PBS and cathelicidin-treated groups (Supplementary Fig. 4B). There were no individual phyla that were differentially altered between PBS and cathelicidin-treated mice.

DISCUSSION

In this translational study, we provide evidence that higher 25(OH)D levels correlate with increased cathelicidin levels in serum and colon of UC patients and that higher serum cathelicidin is associated with decreased histologic inflammation and risk of clinical relapse. We show that cathelicidin mediates a protective association between 25(OH)D and UC clinical and histologic outcomes. We further demonstrate that vitamin D induces cathelicidin production in human colon cells, which exhibited antimicrobial activity against E. coli. Finally, we show that intrarectal cathelicidin reduced the severity of DSS murine colitis but did not impact intestinal microbial dysbiosis.

Although vitamin D induction of cathelicidin in immune cells11 and epithelial cells of the skin,23 bronchial airway,24 and urinary bladder25 has been previously characterized, studies examining the vitamin D–cathelicidin pathway in epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract are lacking. One prior study26 failed to demonstrate 1,25(OH)2D induction (1–200 nM) of cathelicidin in 2 human colon cell lines (HT-29 and FET). Our study is the first to demonstrate the ability of 1,25(OH)2D to stimulate cathelicidin production in human colon cells (DLD1). Cathelicidin mRNA expression was highest at lower 1,25(OH)2D concentrations of 0.01 and 0.1 nM, and this effect was potentiated in the presence of the microbial stimulus LPS. The induction of 1,25(OH)2D at higher concentrations (>1 nM) required the presence of LPS. It is possible that the prior study was unable to induce cathelicidin with 1,25(OH)2D due to the higher concentrations used, which may have exceeded physiologic levels. Another possibility is that costimulation with a microbial factor such as LPS may be needed. Differences in cell differentiation may also possibly account for the difference in response to 1,25(OH)2D, as one prior study demonstrated that only differentiated colonic epithelial cells were able to express cathelicidin.15

A major finding in our study was that lower 25(OH)D levels correlate with decreased serum protein and colonic mRNA levels of cathelicidin in UC patients. In fact, UC patients who were 25(OH)D deficient (<20 ng/mL) had about 10.6-fold less cathelicidin expression from inflamed colon biopsies than UC patients with 25(OH)D >20 ng/mL. Interestingly, prior interventional studies have shown that vitamin D supplementation can increase plasma cathelicidin protein levels in Crohn’s patients27 and cathelicidin mRNA expression from whole blood in ulcerative colitis patients.28 Currently, no studies have evaluated whether vitamin D supplementation can increase colonic cathelicidin levels in inflammatory bowel disease patients. In our UC patients, 25(OH)D was an independent predictor of serum and colonic cathelicidin levels. Furthermore, histologic inflammation was inversely associated with colonic cathelicidin mRNA expression, even after multivariate adjustment. Clinically, our data suggest a beneficial role of higher serum cathelicidin levels in ulcerative colitis patients. Ulcerative colitis patients with baseline histologic inflammation and who later experienced clinical relapse had much lower baseline serum cathelicidin levels. Our findings are consistent with a study by Tran et al,29 which demonstrated that serum cathelicidin levels were inversely associated with disease activity in UC and Crohn’s disease patients. However, this study did not evaluate whether 25(OH)D was associated with cathelicidin in their IBD cohort.

Increased cathelicidin production by human colon cells via vitamin D has many potential physiologic benefits, as cathelicidin has been shown to have anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antifibrotic, and antineoplastic properties. Increased colonic cathelicidin may prevent or attenuate colitis. Indeed, a study by Koon et al30 demonstrated that loss of endogenous cathelicidin through genetic knockout of the murine analog of cathelicidin (mCRAMP) exacerbated DSS colitis. Likewise, previous studies have also shown that exogenous murine cathelicidin administration rectally16 or orally31 via mCRAMP-transformed Lactococcus lactis can attenuate DSS colitis. Our results are consistent with these prior findings, support the anticolitogenic role of cathelicidin, and add to the literature by showing that human cathelicidin (LL37) administered intrarectally in mice can also attenuate DSS colitis.

The vitamin D–cathelicidin pathway may also protect IBD patients from infections and microbial-associated inflammation. A prior study by Hing et al32 showed that exogenous cathelicidin reduces Clostridium difficile–induced colitis and toxin A-mediated enteritis in mice. Another study33 demonstrated that cathelicidin protected mice from E. coli–mediated disease. Our study revealed that vitamin D induction of colonic cathelicidin increases antimicrobial activity against E. coli in vitro. This finding is important because decreased intestinal antimicrobial activity has been implicated to play a role in the pathogenesis of IBD34 and because E. coli may play a facilitative role in flares in ulcerative colitis patients.18 Furthermore, increased cathelicidin may have antifibrogenic effects on IBD. One previous study35 revealed that cathelicidin can reverse colitis-associated intestinal fibrosis by inhibiting collagen synthesis in colonic fibroblasts. Interestingly, low serum cathelicidin has been associated with an increased risk of intestinal strictures in Crohn’s patients.29 Finally, cathelicidin may also mediate the protective effects of vitamin D on the risk of colon cancer, as cathelicidin has been shown to suppress colon cancer development36 and metastases.37

Another finding in our study was that intrarectal administration of human cathelicidin in wild type mice did not mitigate the effects of microbial dysbiosis in colitis. Our results contrast with prior studies demonstrating a link between cathelicidin and intestinal microbial dysbiosis. In one study,38 knockout of endogenous mCRAMP in mice led to intestinal microbial dysbiosis. In another study,39 exogenous intraperitoneal administration of human cathelicidin in type 1 diabetic rat models mitigated intestinal dysbiosis. It is possible our study did not show an effect of cathelicidin on the gut microbiome due to inadequate cathelicidin dosing (at 5 mg/kg), insufficient duration of treatment (14-day course), or ineffective delivery (intrarectal administration may only impact microbiota of left side of colon). Studies evaluating the role of human cathelicidin in microbial intestinal dysbiosis and its relevance to disease processes in IBD patients are warranted.

Our study has several strengths and clinical implications. First, we used patient-level data and human samples to establish relevant and significant links between cathelicidin, vitamin D, and beneficial UC clinical outcomes. Our study provides a rationale for higher vitamin D levels in UC patients and cathelicidin as a biomarker for UC outcomes. Second, we demonstrate vitamin D’s role in inducing cathelicidin in colonic epithelial cells and its anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects. Our results propose that vitamin D treatment could be a way to increase endogenous cathelicidin production in human colon cells. Third, we highlight a protective role of intrarectal cathelicidin in murine colitis. Manipulating cathelicidin levels endogenously through vitamin D treatment or through exogenous cathelicidin administration may be potential therapeutic strategies in IBD. Further studies are needed to explore these pathways.

Our study has some limitations. First, our human study was observational and cannot establish direct causation between 25(OH)D and cathelicidin or between cathelicidin and UC clinical outcomes. To overcome these limitations, we directly treated human colon cells with vitamin D and mice with intrarectal cathelicidin in DSS colitis. Second, we did not measure the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in our patient samples and in vitro human colon cell culture model. VDR expression in IBD patients has been previously shown to not correlate with circulating 25(OH)D.40 We acknowledge that inflammation is inversely associated with VDR expression in IBD patients and that expression of VDR could be a potential confounder in our study. However, we adjusted for the effect of inflammation (both endoscopic and histologic inflammation) in our multivariate models evaluating the associations between 25(OH)D and cathelicidin and between cathelicidin and UC clinical outcomes. Finally, we were unable to establish a direct link between the vitamin D–cathelicidin pathway in our murine model of colitis. Ideally, to link the vitamin D–cathelicidin pathway with colitis, we would treat mice directly with vitamin D, show vitamin D-endogenous induction of colonic cathelicidin, and then evaluate whether increased colonic cathelicidin alters the severity and course of DSS murine colitis. Unfortunately, the vitamin D induction of cathelicidin is not evolutionary conserved in mice,12 and thus we employed an indirect route (via exogenous administration of cathelicidin intrarectally) to evaluate the effects of increased colonic cathelicidin on murine colitis and the intestinal microbiome.

In conclusion, our study provides data supporting a role for cathelicidin in mediating protective effects of vitamin D in UC clinical outcomes and human colonic epithelial cells. We provide mechanistic insights highlighting the ability of vitamin D to induce cathelicidin in human colon cells, which has anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties in vitro and anticolitogenic effects on murine colitis. The therapeutic potential of cathelicidin-based therapies in IBD patients warrants further investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Yan Wu for ordering our mice and other reagents and Renee Robles for assisting with preparing the dextran sodium sulfate reagent.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 25(OH)

vitamin D

- 1

25(OH)D, dihydroxy-vitamin D

- LL37

cathelicidin protein

- CAMP

cathelicidin gene

- mCRAMP

murine cathelicidin gene

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- nM

nanomolar

- mRNA

messenger ribonucleic acid

- siRNA

small interfering ribonucleic acid

- IR

intrarectal

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- UC

ulcerative colitis

- OR

odds ratio

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

area under the curve

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- IL-10

interleukin 10

- RT-PCR

real-time polymerase chain reaction

- OTU

operational taxonomic units,

- DSS

dextran sodium sulfate

Author Contribution: JG and AM planned and designed the study and analyzed the data; JG and SM measured serum vitamin D and cytokine levels from patient samples; MSL assisted with cytokine multiplex assays and cell cultures; JG measured cathelicidin from patient samples, performed vitamin D cell culture experiments, measured cathelicidin and cytokine protein and mRNA from cell cultures, performed siRNA cell culture experiments, and performed antimicrobial assays; JG performed the intrarectal cathelicidin mice treatments and DSS colitis experiments; EC prepared the colon histology slides; GM performed the blinded inflammation scoring of colon histology; SR provided the laboratory support; GM and FV assisted with data analysis; JG drafted the manuscript; all authors interpreted the results and contributed to critical review of the manuscript; JG had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Supported by: National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant K23DK084338, Rabb Research Award

Conflicts of interest: ACM is supported by NIH grant K23DK084338 and Rabb Research Award.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gubatan J, Chou ND, Nielsen OH, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: association of vitamin D status with clinical outcomes in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:1146–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gubatan J, Mitsuhashi S, Longhi MS, et al. Higher serum vitamin D levels are associated with protective serum cytokine profiles in patients with ulcerative colitis. Cytokine. 2018;103:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gubatan J, Mitsuhashi S, Zenlea T, et al. Low serum vitamin D during remission increases risk of clinical relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kabbani TA, Koutroubakis IE, Schoen RE, et al. Association of vitamin D level with clinical status in inflammatory bowel disease: a 5-year longitudinal Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:712–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nielsen OH, Hansen TI, Gubatan JM, et al. Managing vitamin D deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019;10:394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gubatan J, Moss AC. Vitamin D in inflammatory bowel disease: more than just a supplement. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018;34:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, et al. Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G208–G216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu W, Chen Y, Golan MA, et al. Intestinal epithelial vitamin D receptor signaling inhibits experimental colitis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3983–3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ooi JH, Li Y, Rogers CJ, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D regulates the gut microbiome and protects mice from dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis. J Nutr. 2013;143:1679–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xue LN, Xu KQ, Zhang W, et al. Associations between vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and susceptibility to ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Faseb J. 2005;19:1067–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gombart AF. The vitamin D-antimicrobial peptide pathway and its role in protection against infection. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:1151–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bals R, Wang X, Zasloff M, et al. The peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18 is expressed in epithelia of the human lung where it has broad antimicrobial activity at the airway surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9541–9546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schauber J, Rieger D, Weiler F, et al. Heterogeneous expression of human cathelicidin hCAP18/LL-37 in inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hase K, Eckmann L, Leopard JD, et al. Cell differentiation is a key determinant of cathelicidin LL-37/human cationic antimicrobial protein 18 expression by human colon epithelium. Infect Immun. 2002;70:953–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tai EK, Wu WK, Wong HP, et al. A new role for cathelicidin in ulcerative colitis in mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232:799–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vargas Buonfiglio LG, Cano M, Pezzulo AA, et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on the antimicrobial activity of human airway surface liquid: preliminary results of a randomised placebo-controlled double-blind trial. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2017;4:e000211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mirsepasi-Lauridsen HC, Vallance BA, Krogfelt KA, et al. Escherichia coli pathobionts associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32:e00060–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goodman LA. On the exact variance of products. J Am Stat Assoc. 1960;55:708–713. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim JJ, Shajib MS, Manocha MM, et al. Investigating intestinal inflammation in DSS-induced model of IBD. J Vis Exp. 2012;60:e3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Erben U, Loddenkemper C, Doerfel K, et al. A guide to histomorphological evaluation of intestinal inflammation in mouse models. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4557–4576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu H, Zhang G, Minton JE, et al. Regulation of cathelicidin gene expression: induction by lipopolysaccharide, interleukin-6, retinoic acid, and salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5552–5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schauber J, Dorschner RA, Coda AB, et al. Injury enhances TLR2 function and antimicrobial peptide expression through a vitamin D-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yim S, Dhawan P, Ragunath C, et al. Induction of cathelicidin in normal and CF bronchial epithelial cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3). J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6:403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hertting O, Holm Å, Lüthje P, et al. Vitamin D induction of the human antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin in the urinary bladder. Plos One. 2010;5:e15580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schauber J, Dorschner RA, Yamasaki K, et al. Control of the innate epithelial antimicrobial response is cell-type specific and dependent on relevant microenvironmental stimuli. Immunology. 2006;118:509–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Raftery T, Martineau AR, Greiller CL, et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on intestinal permeability, cathelicidin and disease markers in Crohn’s disease: results from a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sharifi A, Hosseinzadeh-Attar MJ, Vahedi H, et al. A randomized controlled trial on the effect of vitamin D3 on inflammation and cathelicidin gene expression in ulcerative colitis patients. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:316–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tran DH, Wang J, Ha C, et al. Circulating cathelicidin levels correlate with mucosal disease activity in ulcerative colitis, risk of intestinal stricture in Crohn’s disease, and clinical prognosis in inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koon HW, Shih DQ, Chen J, et al. Cathelicidin signaling via the Toll-like receptor protects against colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1852–63.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wong CC, Zhang L, Li ZJ, et al. Protective effects of cathelicidin-encoding Lactococcus lactis in murine ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1205–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hing TC, Ho S, Shih DQ, et al. The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin modulates Clostridium difficile-associated colitis and toxin A-mediated enteritis in mice. Gut. 2013;62:1295–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chromek M, Arvidsson I, Karpman D. The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin protects mice from Escherichia coli O157:H7-mediated disease. Plos One. 2012;7:e46476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nuding S, Fellermann K, Wehkamp J, et al. Reduced mucosal antimicrobial activity in Crohn’s disease of the colon. Gut. 2007;56:1240–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yoo JH, Ho S, Tran DH, et al. Anti-fibrogenic effects of the anti-microbial peptide cathelicidin in murine colitis-associated fibrosis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1:55–74.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cheng M, Ho S, Yoo JH, et al. Cathelicidin suppresses colon cancer development by inhibition of cancer associated fibroblasts. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:13–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang J, Cheng M, Law IKM, et al. Cathelicidin suppresses colon cancer metastasis via a P2RX7-dependent mechanism. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2019;12:195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yoshimura T, McLean MH, Dzutsev AK, et al. The antimicrobial peptide CRAMP is essential for colon homeostasis by maintaining microbiota balance. J Immunol. 2018;200:2174–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pound LD, Patrick C, Eberhard CE, et al. Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide: a novel regulator of islet function, islet regeneration, and selected gut bacteria. Diabetes. 2015;64:4135–4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garg M, Royce SG, Tikellis C, et al. The intestinal vitamin D receptor in inflammatory bowel disease: inverse correlation with inflammation but no relationship with circulating vitamin D status. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284818822566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.