Abstract

We describe the effects of pH on the structure and bioavailability of MIDD0301, an oral lead compound for asthma. MIDD0301 interacts with peripheral GABAA receptors to reduce lung inflammation and airway smooth muscle constriction. The structure of MIDD0301 combines a basic imidazole and carboxylic acid function in the same diazepine scaffold, resulting in high solubility at neutral pH. Furthermore, we demonstrated that MIDD0301 can interconvert between a seven-membered ring structure at neutral pH and an acyclic compound at or below pH 3. Both structures have two stable conformers in solution that can be observed by 1H-NMR at room temperature. Kinetic analysis showed opening and closing of the seven-membered ring of MIDD0301 at gastric and intestinal pH, occurring with different rate constants. However, in vivo studies showed that the interconversion kinetics are fast enough to yield similar MIDD0301 blood and lung concentrations for neutral and acidic formulations. Importantly, acidic and neutral formulations of MIDD0301 exhibit high lung distribution with low concentrations in brain. These findings demonstrate that MIDD0301 interconverts between stable structures at neutral and acidic pH without changes in bioavailability, further supporting its formulation as an oral asthma medication.

Keywords: GABAA receptor, benzodiazepine, gastric pH, formulation, asthma

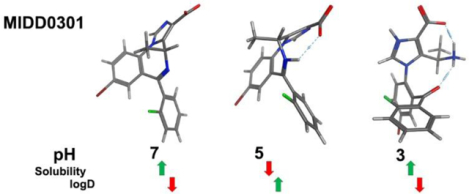

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

MIDD0301 is an oral drug under development for asthma symptom control designed to relax airway smooth muscle (ASM) and to reduce lung inflammation by targeting peripheral gamma amino butyric acid A receptors (GABAAR). The drug’s mechanism of action is consistent with earlier observations that GABAAR modulator propofol1 relaxed ASM.2 Further studies confirmed the expression of GABAARs on ASM cells,3 airway epithelia,4, 5 and airway leucocytes such as CD4+ T cells6 and alveolar macrophages7, supporting the development of GABAAR ligands to treat asthmatic smooth muscle constriction and underlying lung inflammation. GABAARs are heteropentameric chloride ion channels comprised of α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, π, θ and ρ1–3 subunits; commonly exhibiting combinations of two α, two β, and one tertiary subunit.8 MIDD0301 binds these membrane receptors with an EC50 of 72 nM9 and potentiates GABA-induced chloride flux of several GABAAR subtypes at 100 nM.10 Oral administration of 100 mg/kg MIDD0301 reduced eosinophil, CD4+ T cell, and macrophage numbers in the lungs of asthmatic mice (ovalbumin sensitized and challenged model) and reduced airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine challenge.10 Further evidence of anti-inflammatory activity was seen in reduction of IL-17A, IL-4, and TNFα in the lungs of these asthmatic mice.

MIDD0301 is the first allosteric GABAAR modulator that has low brain distribution. Sensorimotor studies conducted at oral dosages of 1000 mg/kg demonstrated no CNS effects and recent immunotoxicity studies with 28 day dosing of 100 mg/kg showed no signs of toxicity and no change in the humoral immune response to T-dependent antigen, dinitrophenyl‐keyhole limpet haemocyanin.9 The half-life of MIDD0301 is greater than 25 h in human and more than 9 h in mouse microsomal preparations. Pharmacokinetic analysis demonstrated a half-life of almost 4 h in the mouse lung. A nebulized dose of 0.8 mg/kg MIDD0301 was sufficient to overcome airway resistance induced with 25 mg/ml methacholine.11 Oral dosages of 50 mg/kg of MIDD0301 were required to achieve pharmacological effects, prompting further investigation of the compound’s gastric stability and bioavailability.

MIDD0301 exhibits a carboxylic acid function connected to a basic imidazobenzodiazepine scaffold. This feature results in pH dependent compound solubility and conversion of the seven membered ring to an open-ring benzophenone structure under acidic conditions. This equilibrium has been evaluated for 1,4-benzodiazepin-2-ones using NMR (diazepam,12 fludiazepam12 and flurazepam13) and UV absorption (diazepam,14 prazepam,15 temazepam16 and nitrazepam17). Furthermore, triazolobenzodiazepine estazolam18 and imidazobenzodiazepine midazolam19 were evaluated under acidic conditions using NMR and UV absorption, respectively. Sternbach reported the formation of 1,4-benzodiazepin-2-ones under basic conditions and speculated that similar but less pronounced pharmacological properties of acyclic aminoacetoamido compounds were due to cyclization in vivo.20 A later report from Hoffmann-LaRoche confirmed the ring opening reaction for imidazobenzodiazepines under acidic conditions in addition to the isolation of a dihydrochloride salt.21

Here, we report detailed evaluation of pH dependent solubility and lipophilicity (logD) of MIDD0301 and structural changes that occur at different pH. Kinects of the ring opening and closing reaction at gastric and intestinal pH were determined by NMR and spectrophotometry. Finally, different formulations were examined to determine if gastrointestinal pH differences influence the in vivo absorption of MIDD0301.

Experimental Section

pH dependent absorbance measurements:

2 μL of a 5 mM solution of closed or open MIDD0301 (see Supporting Information for synthesis and analysis) were added into a 96 well polypropylene plate (Nunc, 249944) followed by the addition of 198 μL of buffered water at different pH. The following buffers were used and adjusted with KCl to an ionic strength of 0.1M: pH 9; 12.5 mM borate buffer, pH 8, 7 and 6; 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 5, 4 and 3; 50 mM acetate buffer; pH 2 and 1; 50 mM phosphoric acid buffer. The solutions were mixed by four times aspiration and dispensed. Two 40 μL aliquots from the same well were transferred into a 384 well plate (Coring UV star, 781801). The plate was incubated at rt for 24 h followed by absorbance detection over a range of 230–400 nm with 2 nm increments (Tecan M1000). 198 μL of buffered water with 2 μL DMSO was used for background subtraction. The absorbance average of two independent measurements in duplicate was plotted versus the wavelength.

Determination of solubility at different pH:

2 mg of closed MIDD0301 was added to 200 μL of buffered water at different pH and agitated with a horizontal shaker in a closed vial for 24 h. The mixtures were transferred to an Eppendorf tube and centrifuged for 5 min at 16000 × g followed by pH determination of the supernatant. Three independent aliquots of 10 μL were added to 190 μL of 50:50 methanol/buffer water (25 mM phosphate buffer, pH 10) and after mixing, 40 μL were transferred into a 384 well plate (Coring UV star, 781801) for UV detection at 270 nm (Tecan M1000). The assay was carried out with three independent measurements for each pH. The concentration of each solution was determined with a calibration curve in 50:50 methanol/buffer water (25 mM phosphate, pH 10).

Mass spectrometry analysis of pH dependent ratio of closed and open MIDD0301:

10 mL of 50 μM aqueous solution of closed MIDD0301 was adjusted to pH 1 using 0.1 M HCl. Before adjusting the pH to 2 using a 10% ammonium hydroxide solution, a 400 μL aliquot taken and labeled as pH 1. This procedure was repeated until pH 9 was reached. Aliquots were kept at rt for 24 h following by final pH determination. The solutions were injected directly into a mass detector with a syringe, needle adapter, and connector without any additional solvent (Shimadzu 2020). The peak heights of 414 m/z and 432 m/z were measured to determine the ratio.

Acid-dependent conversion of closed MIDD0301 determined by 1H-NMR:

1 mg of closed MIDD0301 was dissolved in 500 μL d6-DMSO followed by the addition of 500 μL D2O. The solution was immediately measured by 1H-NMR. Following this measurement, DCl (5.125 M) in D2O was added in small aliquots (0.1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11, 21 μL). The NMR tube was shaken vigorously followed by 1H-NMR measurement.

Stability measurement of closed and open MIDD0301 at different pH:

Four aliquots of 5 μL of a 1 mM solution of closed or open MIDD0301 were added into 384 well plate (Coring UV Star) followed by the addition of 75 μL of buffered water at pH 2 or 8. The solutions were mixed and absorbance at 246 nm were recorded every 30 seconds over a period of 260 min. Buffered water with 5 μL DMSO was used for background subtraction. The average absorbance was plotted versus time and analyzed using first order kinetics to determine k and half-life.

Stability measurement of closed and open MIDD0301 at different pH using 1H-NMR is described in Supporting Information

Determination of logD:

In screw top vial, 200 μL of a 2.5 mM 1-octanol solution of closed MIDD0301 was added to 300 μL of water saturated 1-octanol and 500 μL of 1-octanol saturated buffered water at different pH. The vial was shaken vigorously overnight and allowed to separate for 1h. Three aliquots of 10 μL of the octanol layer were combined with 70 μL of octanol followed by the determination of absorbance at 270 nm using a 384 well plate (Coring UV star) and a Tecan M1000 microplate reader. Three aliquots of 70 μL of the water layer were combined with 10 μL of corresponding buffer and the absorbance determined at 270 nm using a 384 well plate (Coring UV star) and the Tecan M1000. Calibration curves for octanol and water were prepared to determine MIDD0301 concentrations. The assay was carried out in triplicate.

Molecular dynamics using MOE (Chemical Computing Group):

The closed and open MIDD0301 structures were drawn with the builder tool and protonation computed with the protonate 3D function. Interestingly, the imidazole nitrogen was not identified as basic, thus the protonation state of +1 was changed manually for both structures. Conformational search was carried out with LowModeMD with different energy windows.

Pharmacokinetic studies in mice:

Six weeks old female Swiss Webster mice (Charles River Laboratory, WIL, MA) were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions, under standard conditions of humidity, temperature and a controlled 12 h light and dark cycle and had free access to food and water. All animal experiments were in compliance with the University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Animals received intra-gastric gavage of closed or open MIDD0301 formulated in different vehicles at a dose of 25 mg/kg. At 60 min, blood was collected into heparinized tubes via cardiac puncture. Lungs and brain were harvested, and samples were stored in liquid nitrogen until analysis. (n = 4)

Blood samples were thawed on ice, vortexed for 10 s, and a 100 μL aliquot was combined with 400 μL cold methanol containing 300 nM XHE-III-74A22 as internal standard (I.S.). Samples were vortexed for 30 s and centrifuged at 16000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant layer was then transferred into clean tubes and evaporated using a Speedvac concentrator. The residue was reconstituted with 400 μL of methanol and spin-filtered through 0.22 μm nylon centrifugal filter units (Costar). After reconstitution, the samples were diluted if needed and 4,5 diphenylimidazole was added as instrument standard. The injection volume was 5 μL (LC–MS/MS, Shimadzu 8040). Brain and lung tissue samples were thawed, weighed, and homogenized directly into 400 μL or 600 μL methanol, respectively, containing 300 nM XHE-III-74A22 (I.S.) using a Cole Palmer LabGen 7B Homogenizer. Samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 16000 × g at 4 °C. The supernatant was then spin-filtered through 0.22 μm nylon centrifugal filter units (Costar) and evaporated using a Speedvac concentrator. After reconstitution with 200 μL or 400 μL of methanol for brain and lung respectively, 4,5 diphenylimidazole was added after spin-filtration through 0.22 μm nylon centrifugal filter unit. The injection volume was 5 μL (LC–MS/MS, Shimadzu 8040).

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed with Shimadzu Nexera X2 LC30AD series pumps (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Analytes were separated by with an Agilent RRHD Extend-C18 (2.1 mm × 50 mm, 1.8 μm particle size) column with gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The mobile phase was methanol and water (both containing 0.1% formic acid). Time program: 20% B (0 min) → 45% B (2 min) → 99% B (4 min), hold at 99% B (4.75 min), return to 20% B (5 min), hold at 20% B (1.5 min); column temperature: ambient.

Analytes were monitored under positive mode by Shimadzu 8040 triple quadrupole mass analyzer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) electrospray and atmospheric pressure ionization run in dual (DUIS) mode. The following transitions were monitored in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. Ion pairs for closed MIDD0301 were m/z 415.95 > 305.00, m/z 415.95 > 398.00, m/z 415.90 > 357.0, m/z 415.90 > 329.00, open MIDD0301: m/z 433.90 > 276.95, m/z 433.90 > 398.95, m/z 433.90 > 347.00, XHE-III-74A:22 m/z 314.10 > 368.10, m/z 314.10 > 278.10, m/z 314.10 > 296.15. Transition pairs for 4,5-diphenylimidazole were m/z 220.80 > 193.10, m/z 220.80 > 166.90, m/z 220.80 >151.95 and m/z 220.80 > 116.10. Collision energy was optimized for each transition to obtain optimal sensitivity. The mass spectrometer was operated with the heat block temperature of 400 °C, drying gas flow of 15 L/min, desolvation line temperature of 250 °C, nebulizing gas flow of 1.5 L/min, and both needle and interface voltages of 4.5 kV. The response acquisition was performed using LabSolutions software. Standard curves were fitted by a linear regression and the validation samples were calculated back by the calibration curve of that day. The mean and the standard deviation were calculated accordingly. Accuracy was calculated by comparing calculated concentrations to corresponding nominal.

Results and Discussion

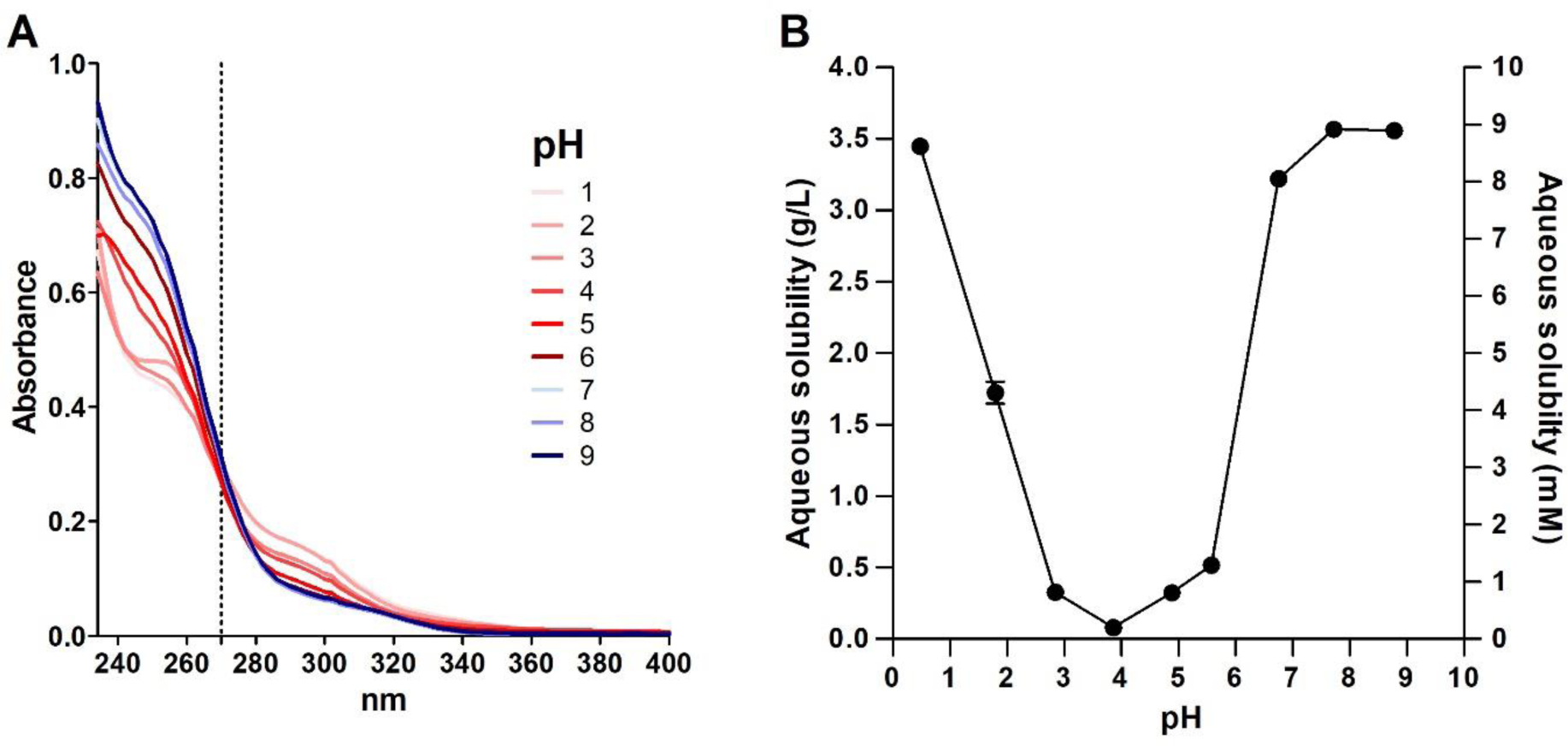

MIDD0301 is formed by reacting the corresponding ethyl ester under basic condition followed by acidification with acetic acid.10 A white precipitate is formed at pH 5 and removed by filtration. To systematically determine the solubility of MIDD0301 in water at different pH, we applied a “shake flask” method and determined the concentration using UV absorption. The results are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A) Absorbance spectra of MIDD0301 in aqueous buffered solution with 1 % DMSO at 50 μM; B) Solubility of MIDD0301 at different pH in water determined after 24 h in a shake flask using UV absorption at 270 nm.

UV measurements of 50 μM MIDD0301 in buffered water over a pH range of 1 to 9 after equilibration for 24 h resulted in spectra with an isosbestic point at 270 nm, at which point the structures of MIDD0301 have a similar total absorbance (Figure 1A). Similar pH dependent absorbances were reported for midazolam with an isosbestic point of 255 nm.19 Subsequently, the aqueous solubility of MIDD0301 at different pH was determined by shake flask method using UV absorbance measurements at 270 nm (Figure 1B). Excellent solubility of MIDD0301 was observed at neutral pH (>3 g/L), whereas less than a 100 mg/L dissolved at pH 3.9. This behavior is unlike midazolam, which is less soluble at neutral pH (70 mg/L) but more soluble at lower pH due to the protonation of the imidazole nitrogen.19 In addition to a basic imidazole nitrogen, MIDD0301 has a carboxylic acid group, thus a neutral zwitterionic species is formed at pH 5 (Figure 3). Similar to amino acids, MIDD0301 has its lowest solubility at the isoelectric point.23

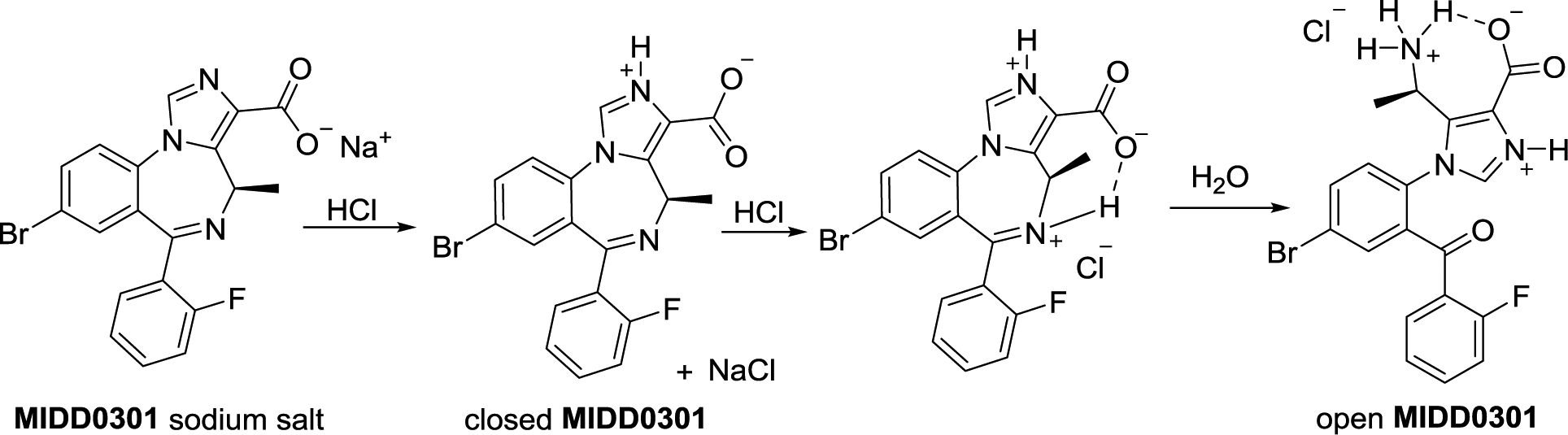

Figure 3.

MIDD0301 and its structures at different pH.

To determine the acid-base behavior of MIDD0301, two different methods were employed that included a titration of a basic MIDD0301 solution with 1 N HCl while recording the pH and a spectrophotometric method using data from Figure 1A.24 The results are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A) Acid titration of 50 μM MIDD0301 dissolved in 0.1 N NaOH in water with 30 % DMSO. The pH was determined after the addition of small quantities of 1 N HCl; inset: pH of the transition determination by non-linear regression. B) Plot of spectral difference between solutions of MIDD0301 at different pH; inset: plot of absorbance difference vs pH to determine the pH of the spectrophotometric transition. The absorbance difference is the sum of the absorbance difference at 252 and 292 nm. The pH of the transition was determined by nonlinear regression.

The acid titration of a basic solution of MIDD0301 resulted in a sharp decrease of the pH after neutralization of the initial NaOH solution (Figure 2A). At pH between 7 and 6 a very small change of the curve was observed but it was less pronounced than the change between pH 5 and 4. Using nonlinear regression, the inflection was calculated to occur at pH 4.69. Additionally, we used the pH-dependent absorbance plots depicted in Figure 1A and plotted the change of each plot for the absorbance at 252 and 292 nm vs the pH to determine the pH of the transition (Figure 2B).25 The pH value of 4.34 was similar to the value calculated by the titration experiment. Investigations with imidazobenzodiazepine midazolam reported pKa values for the imidazole nitrogen of 6.1521 and 6.04,19 however, the acid function of MIDD0301 in the 3 position reduces the basicity of the imidazole nitrogen.

Mass spectrometry was used to evaluate the possibility that, even under mildly acidic conditions, MIDD0301 converts from a closed to an open form causing a change of absorbance and pKa, consistent with the conversion of an imine to a primary amine (Figure 3). Protonation of the imine is expected to activate the electrophilic carbon center, enabling water to act as a nucleophile. The subsequent carbinolamine is expected to form a ketone after proton transfer and cleavage of the carbon nitrogen bond.

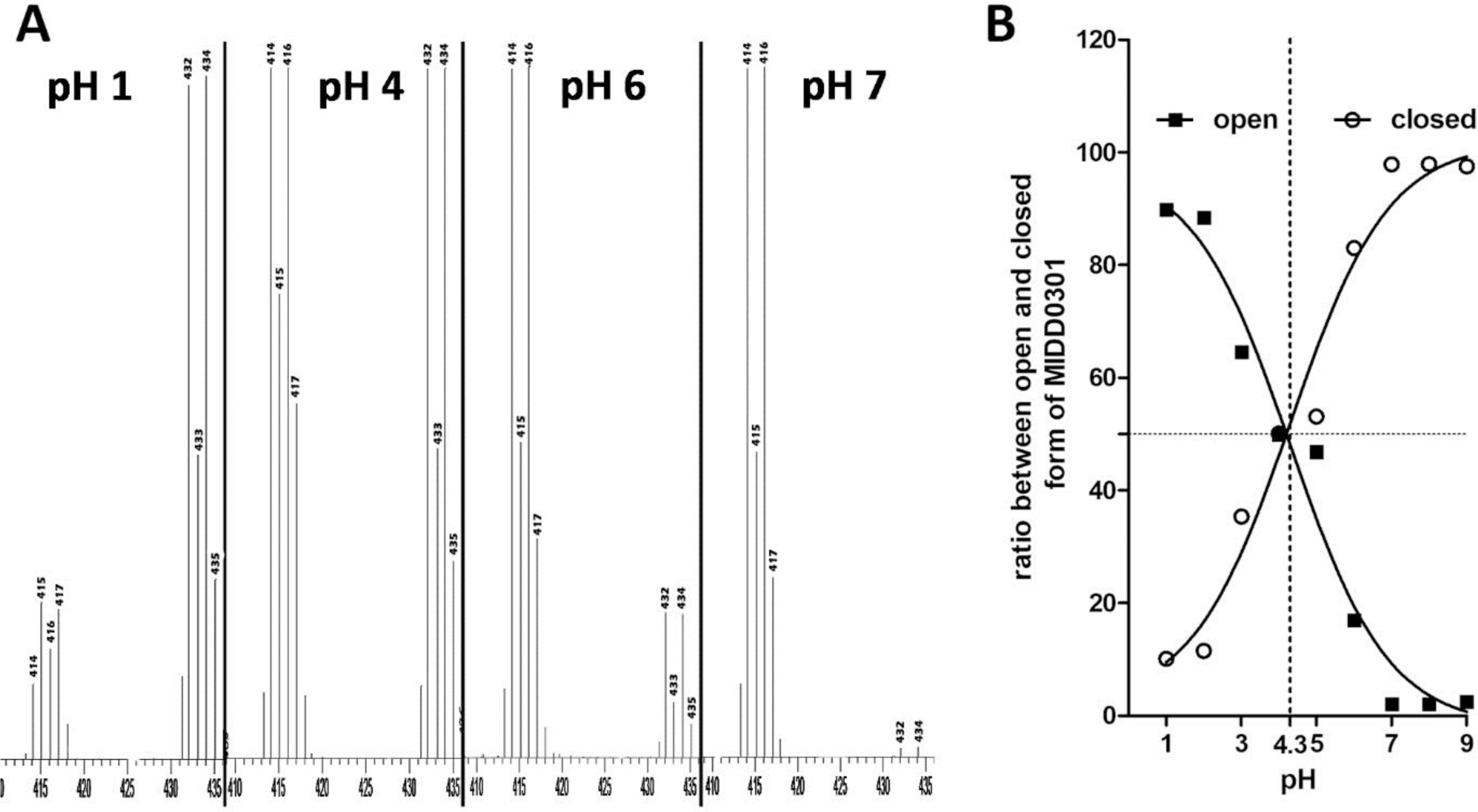

In contrast to the buffered solutions employed for the spectrophotometric analysis of MIDD0301 at different pH, the solutions of MIDD0301 were adjusted with 0.1 M HCl to minimize ion suppression in MS analysis. After 24 h, the solutions were injected directly into the MS to prevent any changes of the equilibrium caused by liquid chromatography. The MS spectra for representative pH values are depicted in Figure 4A and the ratios of the peak heights at 414 m/z (closed MIDD0301) and 432 m/z (open MIDD0301) are plotted vs the pH in Figure 4B.

Figure 4.

A) Representative MS spectra of MIDD0301 at different pH; B) Ratios of peak heights at 414 m/z (closed MIDD0301) and 432 m/z (open MIDD0301). At pH 4.3, both compounds were present at the same peak height ratio.

For the detection of positive ions, closed MIDD0301 has two predominate mass peaks caused by 79Br and 81Br (414 and 416 m/z). In contrast, open MIDD0301 has two equivalent mass peaks at 432 and 434 m/z. At pH 7 and higher, 414/416 m/z is the main mass signal with only 2% of open MIDD0301. This ratio was observed for in vivo quantification of MIDD0301, which included stability assays and pharmacokinetic studies.10 At pH 6, an increase of open MIDD0301 (17%) was observed after 24 h. This implies that the concentration of H3O+ at this pH was high enough to slowly catalyze the hydrolysis of the imine to the amine. The equilibrium between open and closed MIDD0301 in water was observed between pH 4–5. The calculated equilibrium pH of 4.3 was similar to the transition determined for the acid titration (4.69) and using UV spectrophotometry (4.34) (Figure 2). At pH 3 and lower, open MIDD0301 is the major species, however, even in presence of 0.1 N HCl after 24 h 10% of closed MIDD0301 remained. At pH 1, a dimeric species of open MIDD0301 could be detected by MS responsible for the 415/417 m/z MS signal.

Full conversion of closed to open MIDD0301 was achieved in 4 N aqueous HCl after 5 h in a closed vial at 60 °C. The material was isolated after centrifugation, two washes with ethyl acetate and evaporation under vacuum. NMR analysis of open MIDD0301 in d6-DMSO confirmed the presence of two rotamers, consistent with previous reports by Kuwayama et al. for diazepam and fludiazepam.12 The most pronounced 1H-NMR chemical shift differences were observed for the R-methyl group at 1.45 ppm (major) and 1.49 ppm (minor) and the methine protons at 4.11 ppm (major) and 4.23 ppm (minor) with a ratio of 81:19. In addition, separate 13C-NMR signals were observed for carbons for the major and minor rotamer. The R-methyl carbon was observed at 14.94 ppm (major) and 17.75 ppm (minor) and the methine carbon at 41.45 ppm (minor) and 49.35 ppm (major). (for the assignment of all 1H- and 13C-NMR signals see Supporting Information).

When dissolved in D2O/d6-DMSO, open MIDD0301 converted partially into closed MIDD0301 with a ratio of 50:50 based on the 1H-NMR spectra. The pH of this solution was 4, thus the ratio of 50:50 determined by 1H-NMR is consistent with the ratio determined by MS (Figure 4). When open MIDD0301 was dissolved in 0.1 M DCl in D2O/d6-DMSO, 10 % of closed MIDD0301 was observed according to 1H-NMR, which again agreed with the MS data observed for pH 1–2 (Figure 4). Interestingly, Kuwayama et al.12 observed that diazepam under similar conditions formed a 20:80 ratio between open and closed form, whereas fludiazepam, bearing a 2’F substituent like MIDD0301, exhibited a 75:25 ratio. Thus, the 2’F substituent significantly promotes the ring opening reaction and equilibrium towards the open form of benzodiazepines at gastric pH.

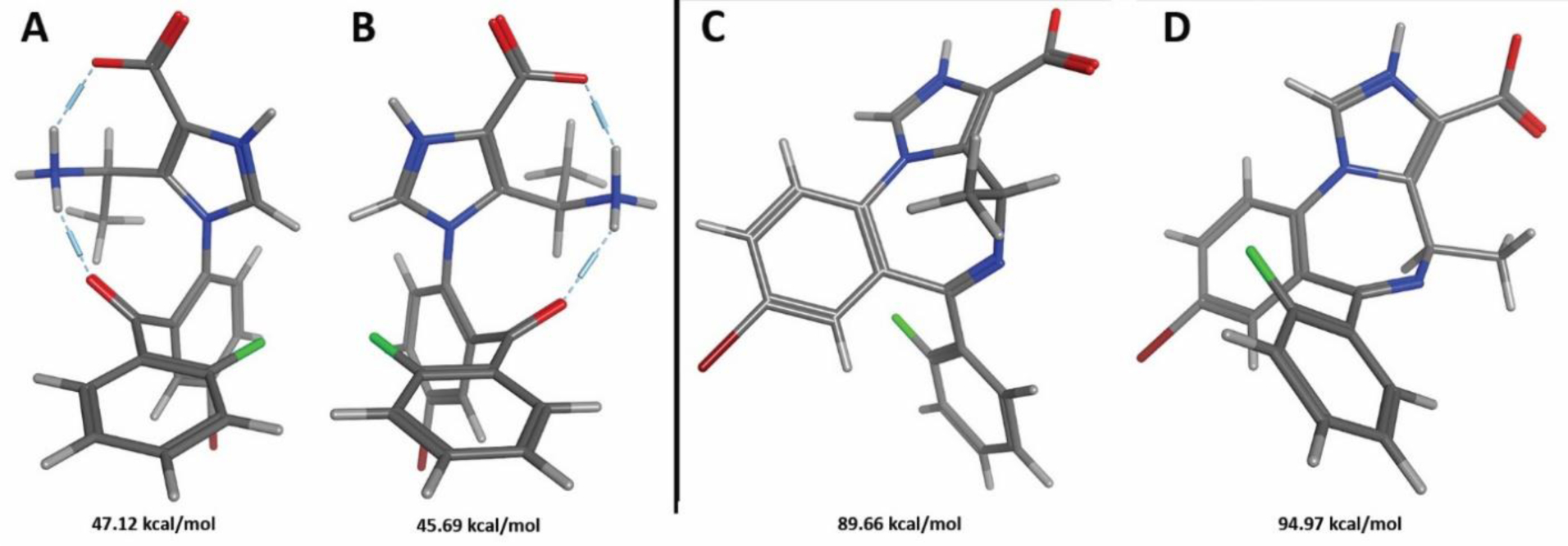

1H-NMR analysis of open MIDD0301 dissolved in 0.1 M DCl in D2O/d6-DMSO gave two baseline separated doublets at 1.38 ppm (major) and 1.47 ppm (minor) for the R-methyl group and a multiplet at 4.20 ppm for the methine proton for both rotamers with ratio of 60:40. Kuwayama et al.12 observed a very similar ratio of 55:45 for the cis and trans rotamer of fludiazepam. Using molecular dynamics, two different stable conformations with different orientation of the imidazole-phenyl system were observed (Figure 5, A and B). Structure A exhibit a P stereochemistry, where structure B has a M configuration.

Figure 5.

Stable conformers for the open MIDD0301 (A and B) and closed MIDD0301 (C and D) determined by molecular dynamics and detected by NMR.

The difference in potential energy between A and B was only 1.43 kcal/mol. However, a conformational search resulted in an interconversion of both structures only when the energy window was increased to 12 kcal/mol. This confirms our findings by NMR that both structures are present at a similar ratio and individual peaks for 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR could be observed at the time scale of detection.

In contrast, 1H-NMR analysis of closed MIDD0301 at pH 8 in D2O/d6-DMSO identified two rotamers with an 80:20 ratio. The R-methyl protons appeared at 1.09 ppm (major) and 1.82 ppm (minor) and the methine proton was found at 4.20 ppm (minor) and 6.47 ppm (major). Interestingly, 13C-NMR signals for the R methyl group at 15.8 ppm and methine carbon (50.8 ppm) were the same for both rotamers, probably due to the longer relaxation time of the carbon nuclei in comparison to the hydrogen nuclei. 1H-13C HSQC NMR analysis showed the coupling between both groups for each rotamer (17.5 ppm and 52.9 ppm) but the carbon signals were absent (see Supporting Information). To confirm the fast interconversion between the conformers of the closed form of MIDD0301, molecular dynamics was used to calculate the potential energy and the energy window for their interconversion. We found that the energy difference between both rotamers was significantly larger than for open MIDD0301 with a ΔE of 5.32 kcal/mol. This explains the large ratio between the rotamers of 80:20. However, an energy window of 6 kcal/mol was sufficient to interconvert both rotamers making this conformational change fast enough to results in unified 13C-NMR signals using a relaxation time of 1.5 seconds. The more stable rotamer (Figure 5C) exhibits a short distance between the methine proton and the carboxylate enabling possible hydrogen bond interaction, which might explain the chemical shift difference for the rotamers of 2.47 ppm.

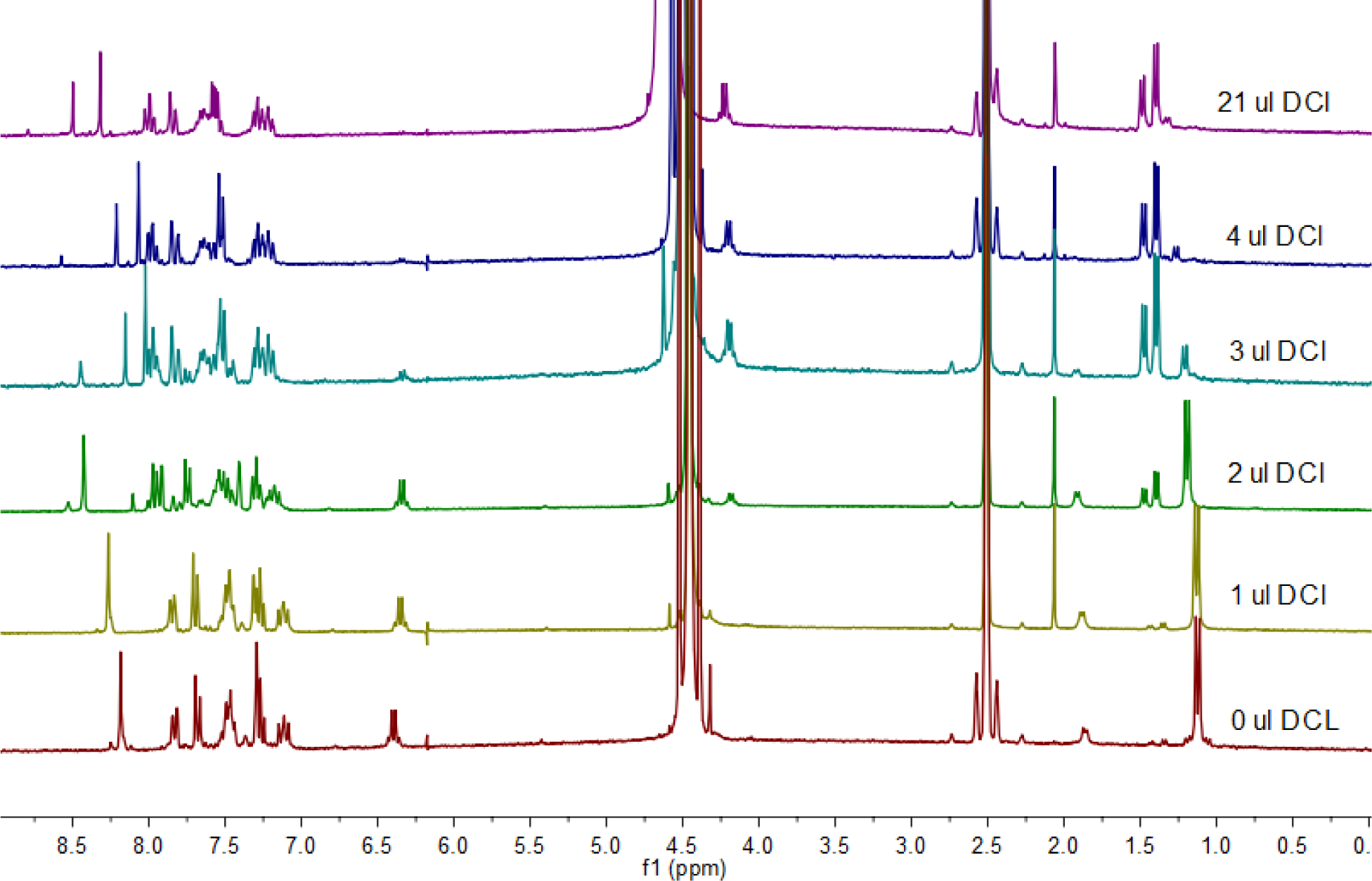

The conversion of open to closed MIDD0301 was investigated under acidic conditions using 1H-NMR analysis. Here, closed MIDD0301 was dissolved in D2O:d6-DMSO at pH 8 and small aliquots of DCl in D2O were added to change the pH. The representative 1H-NMR spectra are depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Representative 1H-NMR spectra recorded for the conversion of closed MIDD0301 sodium salt to open MIDD0301 with the addition of small aliquots of DCl (5.125 M) in D2O. Bottom spectra represent closed MIDD0301 sodium salt followed by spectra recored for the same solution after the addtion of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 21 μL DCl, respectively. The top spectra matched the spectra recorded for open MIDD0301.

As expected, we observed that with the addition of 1 μL of DCl (5.125 M in D2O) at a time, the sodium salt of closed MIDD0301 converted into open MIDD0301 by the disappearance of signals at 1.09 ppm and 6.47 ppm and the appearance of the signals at 1.38/1.47 ppm and 4.20 ppm. Furthermore, the imidazole hydrogen became more deshielded due to the protonation of the adjacent imidazole nitrogen (8.22 ppm to 8.41 ppm). The isolated hydrogen ortho to the bromine substituent becomes more deshielded due to the opening of the seven-membered ring structure (7.26 ppm to 7.89 ppm). Finally, the partially deuterated primary amine protons were visible at 8.67 ppm.

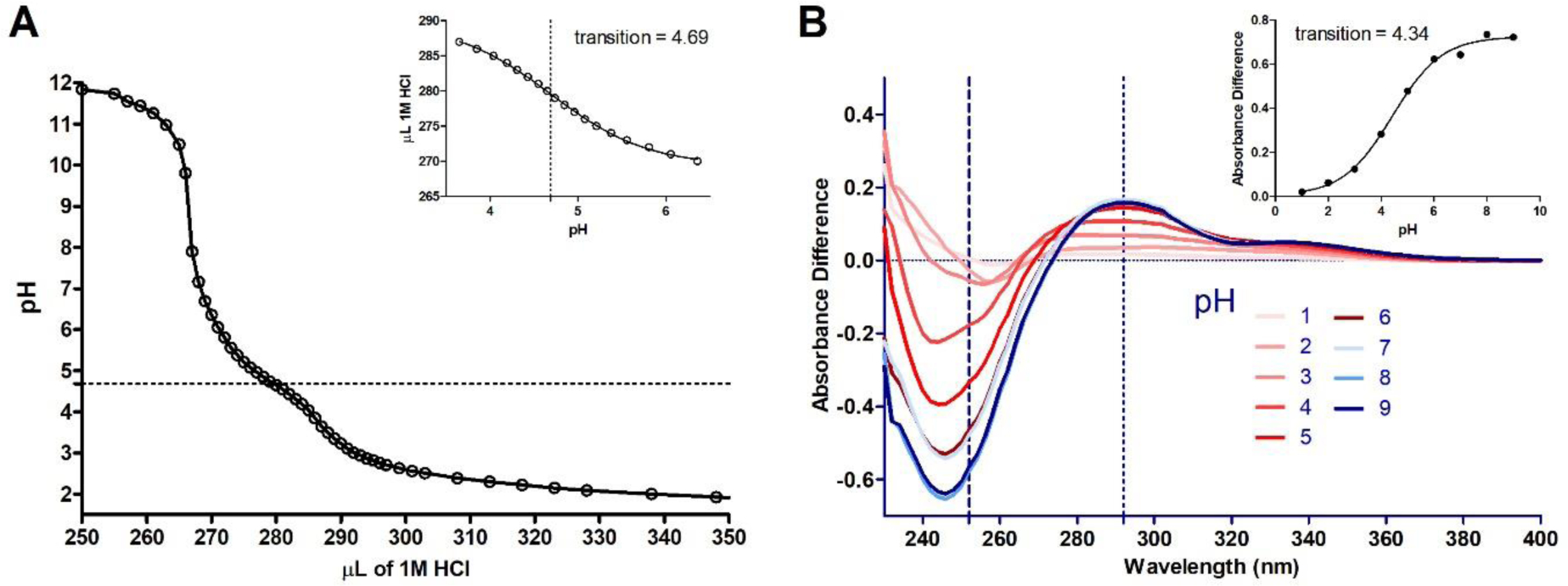

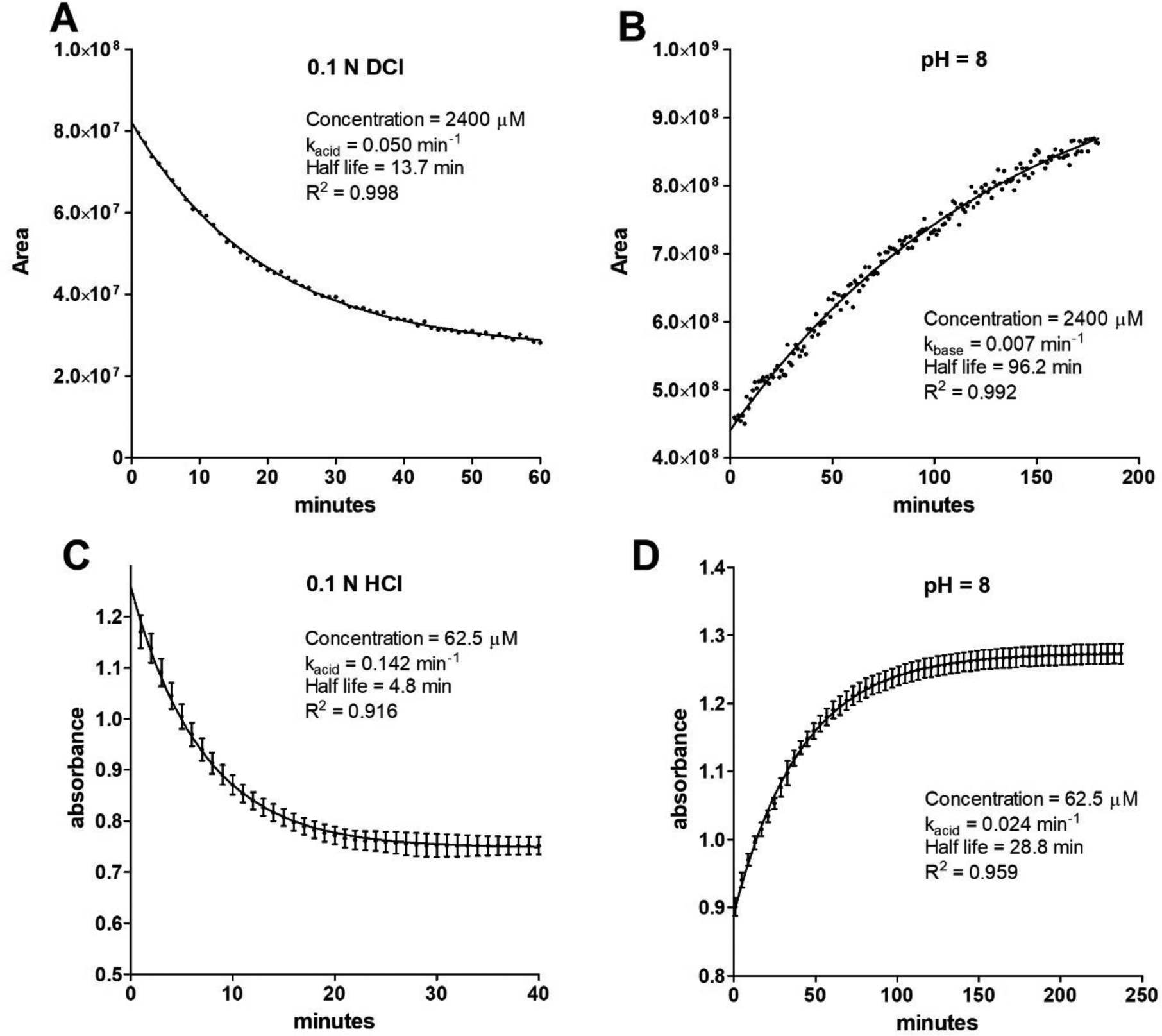

Next, we investigated the kinetics of the conversion of closed to open MIDD0301 in 0.1 N HCl (gastric pH) and conversion of open to closed MIDD0301 at pH 8 (intestinal pH) using 1H-NMR. Here, closed MIDD0301 was dissolved in D2O:d6-DMSO and DCl (5.125 M) was added to achieve a 0.1 N HCl solution. The NMR tube was shaken vigorously, inserted in the spectrometer, and 1H-NMR spectra were measured every minute. The representative 1H-NMR spectra are supplied in the Supporting Information. The area between 1.24–1.06 ppm was integrated for each scan and plotted vs time (Figure 7A). Similarly, open MIDD0301 was dissolved in D2O:d6-DMSO and NaOD (7.23 M in D2O) was added to achieve pH 8. The areas between 1.24–1.06 ppm for each 1H-NMR spectrum was plotted vs time and are depicted in Figure 7B.

Figure 7.

Kinetics of interconversion of open and closed MIDD0301 at different pH. A) Time dependent conversion of 2.4 mM closed MIDD0301 in 50:50 D2O:d6-DMSO adjusted with DCl (5.125 M in D2O) to achieve 0.1 N DCl analyzed by 1H-NMR. The peak areas of the methyl protons were integrated and plotted vs time; B) Time dependent conversion of 2.4 mM open MIDD0301 in 50:50 D2O:d6-DMSO adjusted with 0.5 μL of NaOD (7.23 M in D2O) to pH 8 analyzed by 1H-NMR; C) Time dependent conversion of 62.5 μM closed MIDD0301 in aqueous 0.1 N HCl analyzed by UV absorbance at 246 nm; D) Time dependent conversion of 62.5 μM open MIDD0301 in 50 mM aqueous phosphate buffer adjusted to pH 8 analyzed by UV absorbance at 246 nm. (n = 4)

Assuming pseudo first order kinetics for the conversion of closed to open MIDD0301 in 0.1 N DCl, a kacid of 0.050 min−1 was determined, whereas the conversion of open to closed MIDD0301 at pH 8 occurred at a rate of 0.007 min−1 (kbase). Therefore, the ring opening reaction under these specific conditions was about seven times faster than the ring closing reaction. The half-lives were 13.7 min and 96.2 min, respectively. Although kinetic studies using NMR have the advantage of structural identification, the drawbacks are high concentration, the need for co-solvents to enable high concentrations, and slow acquisition time. To better reflect the conditions of an orally administered drug, spectrophotometry can be carried out at lower concentration, thus omitting the use of cosolvent DMSO and allowing faster acquisition. Based on the absorbance spectra determined for MIDD0301, a wavelength of 246 nm was used to differentiate between closed and open MIDD0301. Applying first order kinetics, a kacid of 0.142 min−1 and a kbase of 0.024 min−1 was calculated (Figure 7, C and D). Comparable to the NMR-based analysis, a seven times faster ring opening reaction was observed. Interestingly, both reactions were accelerated at lower concentration in the absence of DMSO supporting the involvement of a highly charged transition state for this reaction. The half-life for closed MIDD0301 in 0.1 N HCl was 4.8 min, implicating the presence of a significant amount of open MIDD0301 in the stomach. The half-life of open MIDD0301 at pH 8 was 28.8 min. Identical UV and NMR spectra were obtained using closed or open MIDD0301 at the same pH after the equilibrium was reached (see Supporting Information).

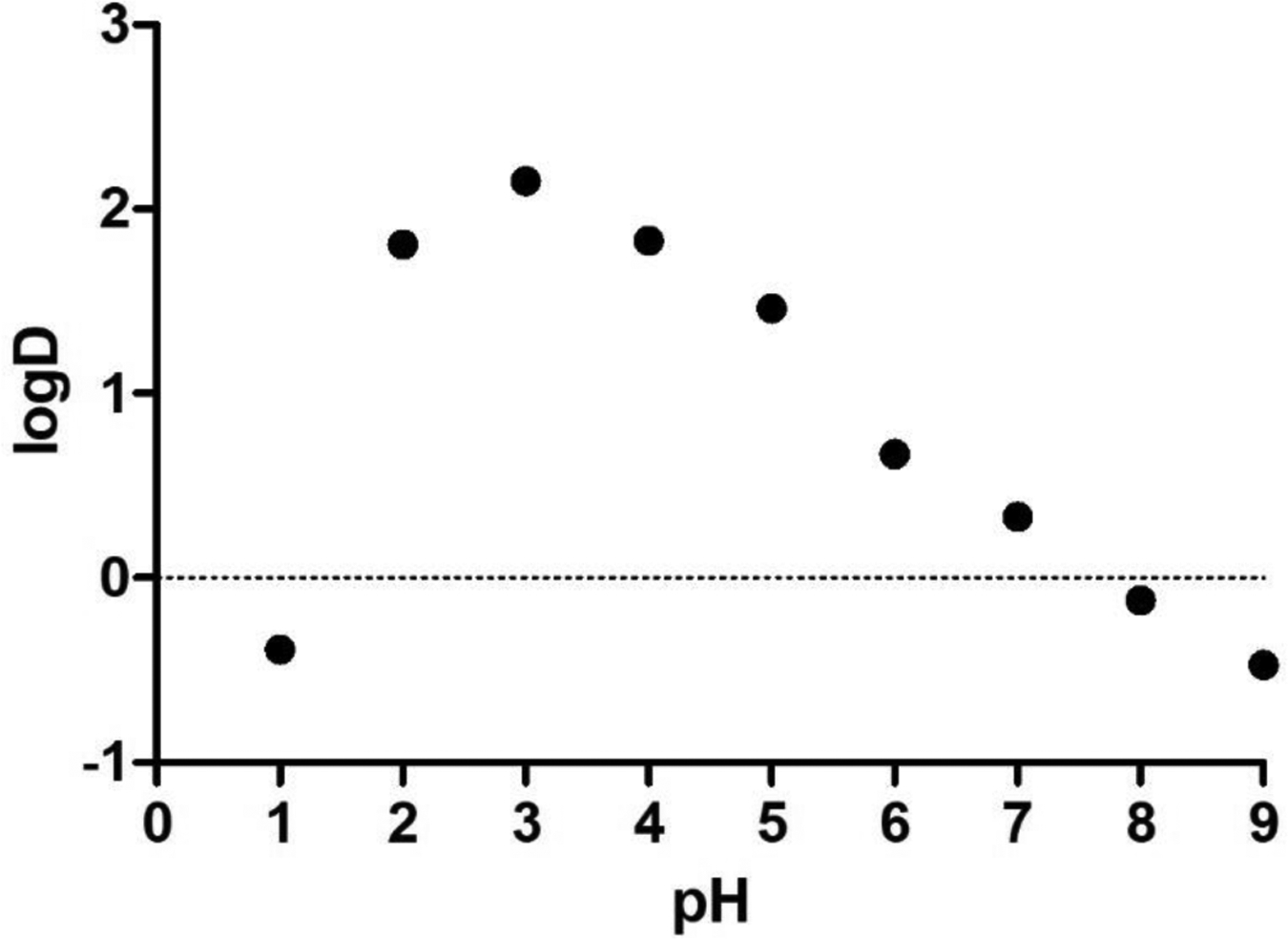

Next, we determined the partition coefficient logDoct/wat of MIDD0301 at different pH, which is important in understanding the absorption profile of orally administered MIDD0301. Here, closed MIDD0301 was dissolved in 1-octanol and partitioned with aqueous buffered solutions in a pH range of 1 to 9 for 24 h. MIDD0301 concentrations were determined for each layer using spectrophotometry. The results are depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Lipophilicity measurement (logDoct/wat) of MIDD0301 at different pH. A 2.5 mM solution of closed MIDD0301 in 1-octanol was partitioned with aqueous buffered solutions with different pH for 24 h. UV absorbance measurements at the isosbestic wavelength of 270 nm were used to determine the concentrations of MIDD0301 in both layers. (n = 3)

The lowest lipophilicity for MIDD0301 was observed at pH 1 due to the formation of open MIDD0301, which has multiple charges. At pH 8 and higher, closed MIDD0301 carboxylate (Figure 3) exhibited low lipophilicity. This behavior corresponds with the high aqueous solubility of MIDD0301 at those pH values (Figure 1B). The highest concentration of MIDD0301 in 1-octanol was observed between pH 2–5, which reflects the overall neutral charge of MIDD0301 due to possible hydrogen bond interactions. For this pH range, the lowest aqueous solubility of MIDD0301 was observed (Figure 1B).

Next, the bioavailability of MIDD0301 formulated at different pH was determined. Groups of four Swiss Webster mice were administered 25 mg/kg oral doses of either closed or open MIDD0301. Blood, lung, and brain concentrations of open and closed MIDD0301 were quantified by LC-MS/MS sixty minutes after administration. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Concentrations of closed and open MIDD0301 sixty minutes after oral administration of MIDD0301 using different formulations.

| Nr | Compound | Vehicle | Concentration of closed MIDD0301 (nM)d | Concentration of open MIDD0301 (nM)d, % of closed MIDD0301 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Lung | Brain | Blood | Lung | Brain | |||

| 1 | Closed MIDD0301 | 2.5 % PEG400a 98 % HPMCb (2 % in water) |

322±65 | 287±46 | 87±27 | 9±33 % | 5±22 % | 3±12 % |

| 2 | Closed MIDD0301 | 40 % propylene glycol 60 % HPMCb (2 % in water) |

239±37 | 455±47 | 104±42 | 6±23 % | 9±22 % | 3±13 % |

| 3 | Closed MIDD0301 Na+ salt | 10 % PEG400 90 % HPMC (2 % in water) |

154±58 | 306±106 | 118±58 | 5±23 % | 5±12 % | 2±12 % |

| 4 | Closed MIDD0301 | 2.5 % PEG400a 98 % HPMCb (2 % in PBSc) |

413±116 | 1745±1121 | 130±24 | 18±144 % | 28±192 % | 4±33 % |

| 5 | Pretreatment with Omeprazole | 100 % HPMCb (2 % in carbonate buffered water, pH 9) |

516±180 | 2046±1155 | 159±33 | 20±84 % | 32±212 % | 4±23% |

| Closed MIDD0301 | 2.5 % PEG400a 98 % HPMCb (2 % in PBSc) |

|||||||

| 6 | Open MIDD0301 | 2.5 % PEG400a 98 % HPMCb (2 % in 0.1 N HCl) |

371±104 | 1792±296 | 130±42 | 14±74 % | 35±82 % | 4±23 % |

polyethylene glycol 400,

hydroxypropyl methylcellulose,

phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4,

data (n = 4) are shown as average±StD.

First, closed MIDD0301 was suspended in polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG400) and diluted further with a 2% solution of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) in water (Table 1, Entry 1). This viscus suspension had a pH of 6.1. One hour after administration of closed MIDD0301 by gavage at a dose of 25 mg/kg in a volume of 3.3 ml/kg, we observed concentrations of 322 nM in blood and 287 nM in lung. The concentration of closed MIDD0301 in the non-perfused brain was 30 % of the lung concentration, representing good tissue selectivity for an oral asthma drug candidate. The concentration of open MIDD0301 was similar in all samples ranging between 2–3 % of closed MIDD0301. A 1:1.5 ratio between propylene glycol and a 2.5 % solution of HPMC in water gave a clear 18.1 mM solution of closed MIDD0301 with a pH of 5.9 (Table 1, Entry 2). This solution was administered at the same dose and volume as Entry 1 and resulted in lower blood concentration of closed MIDD0301 (239 nM) but a higher lung concentration (455 nM). The concentration of open MIDD0301 did not change significantly among the blood, lung, and brain samples. The sodium salt of closed MIDD0301, when dissolved in a 10 % solution of propylene glycol in a 2.5 % aqueous solution of HPMC, had a pH of 8.2 (Table 1, entry 3). When administrated at 25 mg/kg, a blood concentration of 154 nM of closed MIDD0301 was detected after 60 min, which was the lowest blood concentration detected among all formulations. The concentration of closed MIDD0301 was 306 nM in lung and 118 nM in brain. The concentration of open MIDD0301 was 5 nM in blood, 5 nM in the lung and 2 nM in the brain. A superior neutral formulation of closed MIDD0301 was achieved by preparing a 2 % HPMC solution in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) with the addition of 2.5 % PEG400. The viscus mixture exhibited minimal turbidity due to the high solubility of MIDD0301 at that pH (Figure 1, A). After 1 h, a blood concentration of 413 nM and lung concentration of 2046 nM was detected for closed MIDD0301. Thus, the lung concentration of MIDD0301 was six times higher for the neutral buffered formulation than for the non-buffered formulation. The concentration of closed MIDD0301 in brain was 7.8 % of the lung concentrations representing excellent tissue selectivity. To further prevent any conversion of closed to open MIDD0301 in the stomach, mice were pretreated with proton pump inhibitor omeprazole (30 mg/kg) to adjust the gastric pH to 6.7 (Table 1, entry 4).26 Using the same formulation as described in Entry 4, a slightly higher concentration of closed MIDD0301 was observed for blood, lung, and brain. Finally, an acidic formulation using open MIDD0301 was evaluated using 2 % HPMC solution prepared in 0.1 M HCl. The pH of this solution after the addition of 2.5 % PEG400 was 1.8 (Table 1, Entry 5). One hour after treatment, 371 nM of closed MIDD0301 and 14 nM of open MIDD0301 were detected in blood. Interestingly, all concentrations determined in blood, lung and brain were comparable to the neutral formulation of closed MIDD0301 (Table 1, Entry 3). The quantification of open MIDD0301 for all formulations agreed with our kinetic investigation of the ring closing reaction that showed more than 90 % of open MIDD0301 is converted to closed MIDD0301 within 1 h at an intestinal pH of 8 (Figure 7D). Therefore, the kinetic interconversion of MIDD0301 is fast enough to achieve similar concentrations in blood, lung, and brain regardless of open or closed MIDD0301 formulations at different pH for oral administration.

Conclusions

The carboxylic acid function of MIDD0301 significantly increases its aqueous solubility at neutral pH in comparison to classical benzodiazepines. This functionality also decreases the lipophilicity at neutral pH, thus significantly reducing the ability of MIDD0301 to cross the blood brain barrier resulting in less than 10 % of the MIDD0301 lung concentration found in the non-perfused brain under these specific conditions. The tissue selectivity of MIDD0301 is paramount for activating peripheral GABAARs to alleviate lung smooth muscle constriction and lung inflammation without adverse CNS effects.10 MIDD0301 can be administered orally as open MIDD0301 using an acidic formulation allowing ring closure to closed MIDD0301 at intestinal pH or as closed form using a preferred neutral formulation achieving the same bioavailability. For all biological samples, the percentage of open MIDD0301 in comparison to closed MIDD0301 was 4 % or less, confirming that the closed form of MIDD0301 meditates the majority if not all pharmacodynamic effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Beryl R. Forman and Jennifer L. Nemke (Animal Resource Center at UWM) for their guidance and support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (USA) R41HL147658 (L.A.A.), R03DA031090 (L.A.A.), R01NS076517 (J.M.C., L.A.A.), R01HL118561 (J.M.C., L.A.A., D.C.S.), R01MH096463 (J.M.C., L.A.A.) as well as the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Research Foundation (Catalyst grant), the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, and the Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation. In addition, this work was supported by grant CHE-1625735 from the National Science Foundation, Division of Chemistry.

Abbreviations

- ASM

airway smooth muscle

- GABAAR

gamma amino butyric acid type A receptor

- IL-17A

interleukin 17A

- IL-4

interleukin 4

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- CNS

central nervous system

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- MS

mass spectrometry

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- HRMS

high resolution mass spectrometry

- ESI

electron spray ionization

- IT-TOF

ion trap-time of flight

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence

Footnotes

Supporting Information

- Synthesis of open and closed MIDD0301

- NMR analysis of MIDD0301 at different pH

- Table of NMR signals

- Time dependent NMR spectra of closed and open MIDD0301 at pH 2 and 8, respectively

References

- 1.Krasowski MD; Jenkins A; Flood P; Kung AY; Hopfinger AJ; Harrison NL General anesthetic potencies of a series of propofol analogs correlate with potency for potentiation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) current at the GABA(A) receptor but not with lipid solubility. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2001, 297, (1), 338–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedersen CM; Thirstrup S; Nielsen-Kudsk JE Smooth muscle relaxant effects of propofol and ketamine in isolated guinea-pig trachea. Eur J Pharmacol 1993, 238, (1), 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallos G; Yim P; Chang S; Zhang Y; Xu D; Cook JM; Gerthoffer WT; Emala CW Sr. Targeting the restricted alpha-subunit repertoire of airway smooth muscle GABAA receptors augments airway smooth muscle relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2012, 302, (2), 248–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu XW; Wood K; Spindel ER Prenatal nicotine exposure increases GABA signaling and mucin expression in airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011, 44, (2), 222–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiang YY; Wang SH; Liu MY; Hirota JA; Li JX; Ju W; Fan YJ; Kelly MM; Ye B; Orser B; O’Byrne PM; Inman MD; Yang X; Lu WY A GABAergic system in airway epithelium is essential for mucus overproduction in asthma. Nature Medicine 2007, 13, (7), 862–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yocum GT; Turner DL; Danielsson J; Barajas MB; Zhang Y; Xu D; Harrison NL; Homanics GE; Farber DL; Emala CW GABAA receptor alpha4-subunit knockout enhances lung inflammation and airway reactivity in a murine asthma model. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2017, 313, (2), L406–L415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders RD; Grover V; Goulding J; Godlee A; Gurney S; Snelgrove R; Ma D; Singh S; Maze M; Hussell T Immune cell expression of GABAA receptors and the effects of diazepam on influenza infection. J Neuroimmunol 2015, 282, 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen RW; Sieghart W GABA(A) receptors: Subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology 2009, 56, (1), 141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zahn NM; Huber AT; Mikulsky BN; Stepanski ME; Kehoe AS; Li G; Schussman M; Rashid Roni MS; Kodali R; Cook JM; Stafford DC; Steeber DA; Arnold LA MIDD0301 - A first-in-class anti-inflammatory asthma drug targets GABAA receptors without causing systemic immune suppression. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2019, 125, (1), 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forkuo GS; Nieman AN; Kodali R; Zahn NM; Li G; Rashid Roni MS; Stephen MR; Harris TW; Jahan R; Guthrie ML; Yu OB; Fisher JL; Yocum GT; Emala CW; Steeber DA; Stafford DC; Cook JM; Arnold LA A Novel Orally Available Asthma Drug Candidate That Reduces Smooth Muscle Constriction and Inflammation by Targeting GABAA Receptors in the Lung. Mol Pharm 2018, 15, (5), 1766–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yocum GT; Perez-Zoghbi JF; Danielsson J; Kuforiji AS; Zhang Y; Li G; Rashid Roni MS; Kodali R; Stafford DC; Arnold LA; Cook JM; Emala CW Sr. A novel GABAA receptor ligand MIDD0301 with limited blood-brain barrier penetration relaxes airway smooth muscle ex vivo and in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2019, 316, (2), L385–L390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuwayama T; Yashiro T The behavior of 1,4-benzodiazepine drugs in acidic media. IV. Proton and carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of diazepam and fludiazepam in acidic aqueous solution. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1985, 33, (12), 5503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuwayama T; Kato S; Yashiro T [The behavior of 1,4-benzodiazepine drugs in acidic media. VII. Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of flurazepam in acidic aqueous solution]. Yakugaku Zasshi 1987, 107, (4), 318–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han WW; Yakatan GJ; Maness DD Kinetics and mechanisms of hydrolysis of 1,4-benzodiazepines II: oxazepam and diazepam. J Pharm Sci 1977, 66, (4), 573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Archontaki HA; Panderi IE; Gikas EE; Parissi-Poulou M Kinetic study on the degradation of prazepam in acidic aqueous solutions by high-performance liquid chromatography and fourth-order derivative ultraviolet spectrophotometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal 1998, 17, (4–5), 739–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang TJ; Pu QL; Yang SK Hydrolysis of Temazepam in Simulated Gastric Fluid and Its Pharmacological Consequence. J Pharm Sci 1994, 83, (11), 1543–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han WW; Yakatan GJ; Maness DD Kinetics and mechanisms of hydrolysis of 1,4-benzodiazepines III: nitrazepam. J Pharm Sci 1977, 66, (6), 795–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuwayama T; Yashiro T; Kurono Y; Ikeda K The behavior of 1,4-benzodiazepine drugs in acidic media. VI. Hydrogen exchange reaction and proton and carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of estazolam. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1986, 34, (7), 2994–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersin R Solubility and acid-base behaviour of midazolam in media of different pH, studied by ultraviolet spectrophotometry with multicomponent software. J Pharm Biomed Anal 1991, 9, (6), 451–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sternbach LH; Fryer RI; Metlesics W; Reeder E; Sach G; Saucy G; Stempel A Quinazolines and 1,4-Benzodiazepines. VI. Halo-, Methyl-, and Methoxy-substituted 1,3-Dihydro-5-phenyl-2H-1,4-Benzodiazepin-2-ones. J Org Chem 1962, 27, 3788–3796. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walser A; Benjamin LE; Flynn T; Mason C; Schwartz R; Fryer RI Quinazolines and 1,4-benzodiazepines. 84. Synthesis and Reaction of Imidazo[1,5-a][1,4]benzodiazepines. J. Org. Chem 1977, 43, (5), 936–944. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forkuo GS; Guthrie ML; Yuan NY; Nieman AN; Kodali R; Jahan R; Stephen MR; Yocum GT; Treven M; Poe MM; Li G; Yu OB; Hartzler BD; Zahn NM; Ernst M; Emala CW; Stafford DC; Cook JM; Arnold LA Development of GABAA Receptor Subtype-Selective Imidazobenzodiazepines as Novel Asthma Treatments. Mol Pharm 2016, 13, (6), 2026–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tseng HC; Lee CY; Weng WL; Shiah IM Solubilities of amino acids in water at various pH values under 298.15 K. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2009, 285, (1–2), 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez CH; Dardonville C Rapid Determination of Ionization Constants (pK a) by UV Spectroscopy Using 96-Well Microtiter Plates. ACS Med Chem Lett 2013, 4, (1), 142–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen RI; Box KJ; Comer JE; Peake C; Tam KY Multiwavelength spectrophotometric determination of acid dissociation constants of ionizable drugs. J Pharm Biomed Anal 1998, 17, (4–5), 699–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lameris AL; Hess MW; van Kruijsbergen I; Hoenderop JG; Bindels RJ Omeprazole enhances the colonic expression of the Mg(2+) transporter TRPM6. Pflugers Arch 2013, 465, (11), 1613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.