To the Editor,

Over the last two decades, several biologic therapies have emerged for the targeted treatment of severe asthma, defined as asthma inadequately controlled by guideline‐recommended treatment with high‐dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and bronchodilator therapies.1 These biologic therapies target specific mechanisms underlying differing asthma phenotypes. Omalizumab (anti‐immunoglobulin E) is indicated for moderate‐to‐severe allergic asthma,2 and mepolizumab (anti‐interleukin‐5) is indicated for severe eosinophilic asthma.3 Although omalizumab has demonstrated efficacy in clinical studies,4 not all patients achieve good disease control with therapy, some of these patients may also be eligible for mepolizumab treatment. Clinical studies have demonstrated that mepolizumab plus standard of care (SoC) reduces exacerbation frequency, decreases oral corticosteroid (OCS) use, and improves health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), asthma control (Asthma Control Questionnaire [ACQ]‐5), and lung function versus placebo in severe eosinophilic asthma.5, 6, 7, 8

Previously, we performed a post hoc analysis of mepolizumab efficacy in patients from SIRIUS (NCT01691508) and MENSA (NCT01691521) who had previously received omalizumab treatment.9 The analysis included patients treated with intravenous (IV) mepolizumab; the results of each trial are presented separately due to differences in the study populations (eg, SIRIUS patients were OCS dependent). The current post hoc meta‐analysis describes the efficacy of the approved mepolizumab 100 mg SC dose in patients with prior omalizumab use using a pooled data from MENSA and MUSCA (NCT02281318), providing a more robust analysis.

MENSA and MUSCA were randomized, double‐blind, phase III trials7, 8 enrolling patients aged ≥12 years, with ≥2 exacerbations in the prior year requiring systemic corticosteroids (SCS) despite treatment with ICS and additional controller medication(s), blood eosinophil counts ≥150 cells/μL at screening or ≥300 cells/μL in the prior year, and airflow obstruction. MENSA patients received mepolizumab 75 mg IV or 100 mg SC, or placebo, every 4 weeks for 32 weeks. MUSCA patients received mepolizumab 100 mg SC or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. In both studies, treatment was additional to stable SoC medication; concurrent omalizumab use was excluded (omalizumab use within 130 days of screening was an exclusion criterion for both studies). Only the approved mepolizumab dose, 100 mg SC, was included in this meta‐analysis.

Endpoints assessed included the annualized clinically significant exacerbation rate (asthma worsening requiring SCS, emergency department (ED) visit or hospitalization; primary endpoint), exacerbations requiring ED visit/hospitalization and exacerbations requiring hospitalization; change from baseline in prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1), St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score, and ACQ‐5 score; proportions of SGRQ and ACQ‐5 responders (≥4‐point and ≥0.5‐point reductions from baseline, respectively); and change from baseline in blood eosinophil count (secondary endpoints). Exacerbation endpoints were analyzed using negative binomial regression (with logarithm of time on treatment as an offset variable); lung function, HRQoL, and eosinophil counts were analyzed with mixed‐model repeated measures. Responder analyses were analyzed using logistic regression, all including adjustment for covariates (treatment, baseline OCS therapy [yes vs no], region, exacerbations in the prior year [ordinal variable], baseline value (where applicable), and baseline percent‐predicted FEV1 (excluding lung function analysis). Estimated treatment differences were combined across studies using inverse variance‐weighted fixed‐effects meta‐analysis.

Of 936 patients, 468 received mepolizumab 100 mg SC and 468 received placebo, with 14% (n = 65 and 67, respectively) in each group having previously used omalizumab. As expected, patients with prior omalizumab use had more severe disease than those without (Table 1). In particular, patients with prior omalizumab use tended to be former smokers, had longer asthma duration, reported more OCS use and exacerbations, had worse lung function, HRQoL and disease control, and higher blood eosinophil counts and immunoglobulin E levels than those with no prior omalizumab use.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Prior omalizumab use | No prior omalizumab use | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mepolizumab (N = 65) | Placebo (N = 67) | Mepolizumab (N = 403) | Placebo (N = 401) | Prior omalizumab use (N = 132) | No prior omalizumab use (N = 804) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 52.3 (13.1) | 51.8 (12.7) | 50.0 (14.4) | 50.7 (13.7) | 52.1 (12.8) | 50.4 (14.1) |

| Female, n (%) | 36 (55) | 43 (64) | 229 (57) | 240 (60) | 79 (60) | 469 (58) |

| Former smoker, n (%) | 22 (34) | 21 (31) | 99 (25) | 112 (28) | 43 (33) | 211 (26) |

| Duration of asthma, years, mean (SD) | 25.2 (15.8) | 22.8 (14.3) | 19.0 (13.4) | 19.0 (14.9) | 24.0 (15.1) | 19.0 (14.2) |

| Maintenance OCS use, n (%) | 42 (65) | 29 (43) | 74 (18) | 82 (20) | 71 (54) | 156 (19) |

| Exacerbations in prior year, n (%) | ||||||

| 2 | 33 (51) | 28 (42) | 215 (53) | 245 (61) | 61 (46) | 460 (57) |

| 3 | 9 (14) | 16 (24) | 87 (22) | 78 (19) | 25 (19) | 165 (21) |

| ≥4 | 23 (35) | 23 (34) | 101 (25) | 78 (19) | 46 (35) | 179 (22) |

| Exacerbations in prior year requiring ED visit/hospitalization, n (%) | ||||||

| >1 | 19 (29) | 23 (34) | 133 (33) | 133 (33) | 42 (32) | 266 (33) |

| ≥2 | 8 (12) | 13 (19) | 71 (18) | 59 (15) | 21 (16) | 130 (16) |

| Exacerbations in prior year requiring hospitalization, n (%) | ||||||

| >1 | 15 (23) | 21 (31) | 87 (22) | 82 (20) | 36 (27) | 169 (21) |

| ≥2 | 7 (11) | 10 (15) | 38 (9) | 33 (8) | 17 (13) | 71 (9) |

| Pre‐BD % predicted FEV1, mean (SD) | 54.7 (17.98) | 55.9 (15.96) | 59.6 (16.45) | 60.8 (17.01) | 55.3 (16.93) | 60.2 (16.73) |

| SGRQ total score, mean (SD) | 51.2 (18.0) | 56.3 (17.7) | 47.0 (18.7) | 44.9 (19.0) | 53.8 (18.0) | 46.0 (18.9) |

| ACQ‐5 score, mean (SD) | 2.38 (1.22) | 2.78 (1.10) | 2.23 (1.16) | 2.12 (1.17) | 2.58 (1.17) | 2.17 (1.16) |

| Blood eosinophil count, cells/μL, | ||||||

| Geo mean (SD loge) | 320 (0.949) | 440 (0.817) | 310 (0.969) | 320 (0.939) | 380 (0.895) | 320 (0.953) |

| Median (range) | 340 (0‐1800) | 390 (0‐3600) | 330 (0‐14 000) | 350 (0‐3700) | 390 (0‐3600) | 340 (0‐14 000) |

| Total IgE, IU/mL, geo mean (SD loge) | 172.4 (1.16) | 204.9 (1.33) | 169.7 (1.50) | 154.8 (1.51) | 188.3 (1.25) | 162.0 (1.50) |

Abbreviations: ACQ‐5, Asthma Control Questionnaire 5‐point scale; BD, bronchodilator; CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1s; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IU, international unit; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SD, standard deviation; SGRQ, St George's Respiratory Questionnaire.

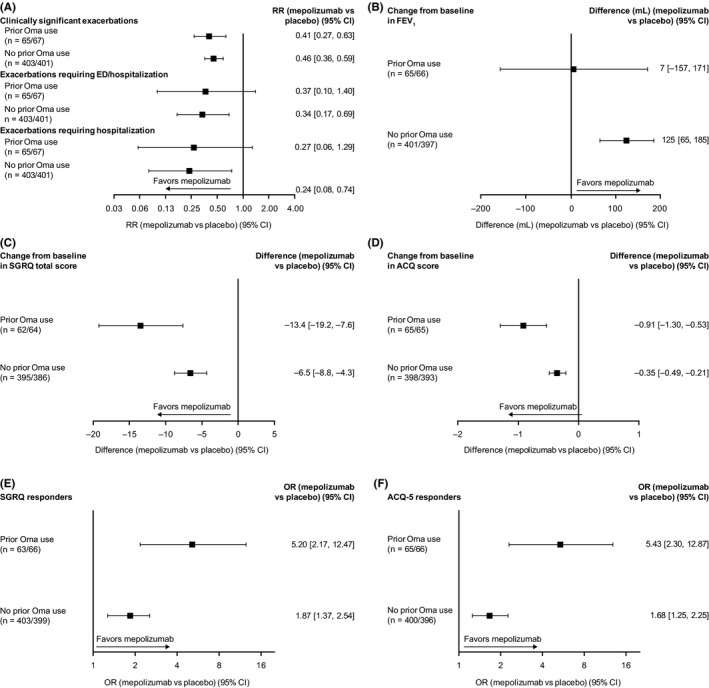

Clinically relevant reductions of ≥54% in annualized clinically significant exacerbation rates with mepolizumab versus placebo were observed irrespective of prior omalizumab use, consistent with our previous analysis (Figure 1A).9 Although studies were 24‐32 weeks in duration, an annualized exacerbations rate was calculated and is presented here; enrollment was over a 1‐year period to address any potential seasonal effect. Additionally, mepolizumab reduced the frequency of severe events requiring ED visits or hospitalization, or hospitalization only, versus placebo. Improvements from baseline in FEV1 of 125 mL with mepolizumab versus placebo were observed in patients with no prior omalizumab use; there was no change in FEV1 in patients with prior omalizumab use (Figure 1B). This reflects opposing findings in the two trials; a worsening in FEV1 was seen in the prior omalizumab group from the MENSA trial, likely due to low patient numbers, in contrast to an improvement in the same group from the MUSCA trial (data not shown). As with our previous analysis,9 mepolizumab improved HRQoL and disease control, as indicated by greater reductions in SGRQ and ACQ‐5 scores versus placebo, regardless of prior omalizumab use (Figure 1C, D). These results were further supported by SGRQ and ACQ‐5 responder analyses, in which mepolizumab increased the proportion of patients with clinically significant ≥ 4‐point and ≥0.5‐point score improvements from baseline, respectively, irrespective of omalizumab use (Figure 1E,F). There was a trend for greater SGRQ and ACQ‐5 score improvements in patients who had prior omalizumab use versus those without, likely due to the former patients’ higher morbidity leading to greater capacity for improvements. However, a limitation of this analysis was the small number of patients in the prior omalizumab use group, which resulted in large confidence intervals. Finally, mepolizumab reduced blood eosinophil counts from baseline by 79% and 81% versus placebo in patients with and without prior omalizumab use, respectively.

Figure 1.

Treatment responses to mepolizumab versus placebo in patients with prior or no prior omalizumab use. ‘n = ‘represents the number of patients on mepolizumab and placebo, respectively. Clinically significant exacerbations were defined as asthma worsening requiring systemic corticosteroid (intravenously or orally for ≥3 d, or single intramuscular dose), or ED visit or hospitalization; SGRQ responders defined as patients with a ≥4‐point improvement in total score; ACQ‐5 responders defined as patients with a ≥0.5‐point improvement in score. ACQ‐5, Asthma Control Questionnaire 5‐point scale; CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; FEV 1, forced expiratory volume in 1s; Oma, omalizumab; OR, odds ratio; RR, rate ratio; SGRQ, St George's Respiratory Questionnaire

Overall, these results indicate that mepolizumab 100 mg SC reduced exacerbation frequency and improved HRQoL and asthma control (ie, ACQ‐5) versus placebo (added to SoC) in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma with and without prior omalizumab use. This is consistent with a previous analysis that examined the effect of prior omalizumab use in the SIRIUS and MENSA studies separately and included the mepolizumab 75 mg IV dose.9 Together, these data suggest that eligible patients are likely to benefit from mepolizumab irrespective of their omalizumab therapy history.

In conclusion, this meta‐analysis provides further support for mepolizumab treatment benefits in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma, irrespective of prior omalizumab use.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

DJB, SWY, and CMP are employees of GSK and hold stocks/shares. FCA was employed by GSK during the time of the analysis and holds stock/shares in GSK. SH has received honoraria for lectures from Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca K.K., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Novartis Pharma K.K., Sanofi K.K., Teijin Pharma, and Torii Pharmaceutical. MH has received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, GSK, Roche, and Sanofi. MCL has received grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, MedImmune, and Mereo BioPharm.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Anonymized individual participant data from the studies listed within this publication and their associated documents can be requested for further research from http://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, including development of the initial draft from the source data, assembling tables and figures, collating authors comments, grammatical editing and referencing) was provided by Elizabeth Hutchinson PhD, CMPP, at Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK.

Funding information

This analysis (GSK ID: 208116) and the original MENSA and MUSCA studies (GSK ID: MEA115588/NCT01691521, and GSK ID: 200862/NCT02281318, respectively) were funded by GSK.

REFERENCES

- 1. GINA . Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. https://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention. Accessed October, 2018.

- 2. Novartis . Omalizumab (XOLAIR) highlights of prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/103976s5224lbl.pdf; http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/003860/WC500198037.pdf. Accessed October, 2018.

- 3. GlaxoSmithKline . Mepolizumab (NUCALA) highlights of prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125526s004lbl.pdf; http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/003860/WC500198037.pdf. Accessed October, 2018.

- 4. Corren J, Kavati A, Ortiz B, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in children and adolescents with moderate‐to‐severe asthma: a systematic literature review. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017;38(4):250‐263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9842):651‐659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al. Oral glucocorticoid‐sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1189‐1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1198‐1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chupp GL, Bradford ES, Albers FC, et al. Efficacy of mepolizumab add‐on therapy on health‐related quality of life and markers of asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma (MUSCA): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group, multicentre, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(5):390‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Magnan A, Bourdin A, Prazma CM, et al. Treatment response with mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma patients with previous omalizumab treatment. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1335‐1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]