Abstract

Different Mechanisms of DEHP-induced Hepatocellular Adenoma Tumorigenesis in Wild-type and Pparα-null Mice: Kayoko Takashima, et al. Department of Preventive Medicine, Shinshu University Graduate School of Medicine—Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) exposure is thought to lead to hepatocellular hypertrophy and hyperplasia in rodents mediated via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα). A recent study revealed that long-term exposure to relatively low-dose DEHP (0.05%) caused liver tumors including hepatocellular carcinomas, hepatocellular adenomas, and chologiocellular carcinomas at a higher incidence in Pparα-null mice (25.8%) than in wild-type mice (10.0%). Using tissues with hepatocellular adenoma, microarray (Affymetrix MOE430A) as well as, in part, real-time quantitative PCR analysis was conducted to elucidate the mechanisms of the adenoma formation resulting from DEHP exposure in both genotyped mice. The microarray profiles showed that the up- or down-regulated genes were quite different between hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type and Pparα-null mice exposed to DEHP. The gene expressions of apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 (Apaf1) and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha (Gadd45a) were increased in the hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice exposed to DEHP, whereas they were unchanged in corresponding tissues of Pparα-null mice. On the other hand, the expressions of cyclin B2 and myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 were increased only in the hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice. Taken together, DEHP may induce hepatocellular adenomas, in part, via suppression of G2/M arrest regulated by Gadd45a and caspase 3-dependent apoptosis in Pparα-null mice, but these genes may not be involved in tumorigenesis in the wild-type mice. In contrast, the expression level of Met was notably increased in the liver adenoma tissue of wild-type mice, which may suggest the involvement of Met in DEHP-induced tumorigenesis in wild-type mice.

Keywords: Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, Tumorigenesis, Apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1, DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha

Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) is a commonly used industrial plasticizer which is used in the synthesis of plastics to improve their pliability and elasticity. These plastics are used extensively in medical devices, plastic wrap, plastic gloves, plastic food packages and other consumer products. Animal studies using DEHP have revealed toxicities including hepatocarcinogenesis1), and a plausible endocrine disruptive effect has also recently attracted attention. Therefore, DEHP has been replaced with alternative plasticizers such as di-isononyl phthalate. In 2002, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) banned the use of DEHP in medical devices, baby toys and food packaging which contact fat and fatty foods directly. In 1982, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified DEHP in Group 2B (possibly carcinogenic to humans). However, in 2000, the IARC re-evaluated DEHP, placing it in the Group 3 category, which is for chemicals not classified as carcinogenic to humans2).

DEHP is a representative peroxisome proliferator (PP) in rodents. PPs such as the clinically used fibrate drug clofibrate and the widely-used experimental compound Wy-14,643, increase peroxisome numbers, up-regulate peroxisomal beta-oxidation, and cause hepatocellular hypertrophy and hyperplasia when administered to rats and mice3).

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα), a nuclear receptor, mediates the biological activities of PPs. In the study of wild-type and Pparα-null mice fed a diet containing 0.1% Wy-14,643 for 11 months, 100% of wild-type mice had multiple hepatocellular neoplasms, including adenomas and carcinomas, while Pparα-null mice were tumor-free4). Two hypotheses have been advanced to account for the mechanism of carcinogenesis by PP3). One is the oxidative stress hypothesis whereby increased β-oxidation induced by PP results in excessive production of reactive oxidative species (ROS)5) leading to DNA damage and cancer3,6,7). Another hypothesis is that imbalance in hepatocyte growth control results in increased cell proliferation and suppression of apoptosis thereby disrupting hepatocyte growth control3). It is likely that the mechanism is a combination of ROS and altered cell proliferation. Indeed, PP-induced cell proliferation is observed in the liver of wild-type mice but not in Pparα-null mice treated with Wy-14,643. In addition, PPARα-dependent alterations in cell cycle regulatory proteins are likely to contribute to the hepatocarcinogenicity of peroxisome proliferators8). Apoptosis was also reported to be suppressed by the PP, nafenopin, possibly through inhibition of transforming factor-beta 1-induced apoptosis9,10). Finally, a microRNA cascade under control of PPARα was found to lead to induction of c-Myc and its downstream target genes resulting in enhanced hepatocellular proliferation11).

A recent study using the Pparα-null and wild-type mice revealed that the incidences of liver tumors including hepatocellular carcinomas, hepatocellular adenomas, and chologiocellular carcinomas were higher in Pparα-null mice exposed to DEHP than in wild-type mice12). In that study, the mechanism of tumorigenesis was investigated using the normal tissues of DEHP-exposed mice, and it was demonstrated that inflammation and protooncogenes altered by 0.05% DEHP-derived oxidative stresses may be involved in the tumorigenesis found in Pparα-null mice, but not in wild-type mice. However, the mechanism was not determined.

Tumorigenesis in Pparα-null mice after low-dose DEHP exposure is Pparα-independent. To determine the mechanism, we examined gene expression profiles in hepatocellular adenoma tissues as well as control livers of wild-type and Pparα-null mice using microarray data. We found the gene expression related to G2/M phase and caspase 3-dependent apoptosis pathways were different in Pparα-null and wild-type mice. Apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 (Apaf1) and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha (Gadd45a) were increased only in wild-type mice. These results indicate that induction of Apaf1 and Gadd45a is inhibited in Pparα-null mice under low-dose DEHP exposure. Thus, the progression of the G2/M phase and suppression of caspase 3-dependent apoptosis may lead to PPARα-independent hepatocellular adenoma formation.

Materials and Methods

Animal experiment protocols

This study was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation of the Shinshu University Animal Center. Pparα-null mice with a Sv/129 genetic background were bred as described elsewhere13), and with wild-type Sv/129 mice they were used to identify PPARα-dependent or -independent hepatic tumor formation caused by DEHP. All mice were housed in a temperature and light controlled environment (25°C, 12 h light/dark cycle), and maintained on stock rodent chow and tap water ad libitum. Diet containing DEHP (0.01 and 0.05%) were prepared with the rodent chow every two weeks, according to the method of Lamb et al.14) The mice were given diets containing 0, 0.01% or 0.05% DEHP throughout the experiment (from three weeks to 22 months of age) and were sacrificed by decapitation at about 23 months of age. Livers were collected to investigate DEHP-mediated pathological changes. Small portions of livers were stored at −80°C until use. The mechanism of DEHP tumorigenesis was investigated using livers of control and hepatic tumor tissues of 0.01% and 0.05% DEHP-exposed mice with hepatocellular adenomas.

Microarray analysis

Samples of normal or hepatocellular adenoma tissue of wild-type and Pparα-null mice exposed to 0 or 0.05% DEHP, respectively, were homogenized using Mill Mixer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and zirconium beads, and total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). The purity of the RNA was analyzed by gel electrophoresis after confirming the 260/280 nm ratio to be between 2.0 and 2.2. Microarray analysis was conducted using GeneChip® MOE430A probe arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA. USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Superscript Choice system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and T7- (dT) 24-oligonucleotide primer (Affymetrix) were used for cDNA synthesis, cDNA Cleanup Module (Affymetrix) was used for purification, and BioArray High yield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit (Enzo Diagnostics, Farmingdale, NY, USA) for synthesis of biotin-labeled cRNA. Ten micrograms of fragmented cRNA was hybridized to a MOE430A probe array for 18 h at 45°C at 60 rpm, after which the array was washed and stained by streptavidin-phycoerythrin using Fluidics Station 400 (Affymetrix) and scanned by Gene Array Scanner (Affymetrix). The digital image files were processed by Affymetrix Microarray Suite version 5.0. and the intensities were normalized for each chip by setting the mean intensity to the median (per chip normalization). The results of the DNA microarray were analyzed using GeneSpring GX 7.3 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The relative increase or decrease in mRNA abundance for each gene was reported as a fold-change relative to the values of normal tissue in the control group.

Real-time quantitative PCR Analysis

cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using Ominiscript Reverse Transcription (QIAGEN, Tokyo, Japan). Reverse transcription was performed on a DNA Engine Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) using QIAGEN One Step RT-PCR Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Of the up-regulated or down-regulated genes obtained from microarray analysis, analyses of some specific genes thought to be related to the DEHP-induced tumorigenesis of hepatocellular adenomas were conducted by real-time quantitative PCR using GeneAmp5700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Specific primers were generated using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems) or purchased from TAKARA BIO (Otsu, Shiga, Japan). The following primers were generated using Primer Express software and synthesized at Operon Biotechnologies (Tokyo, Japan): myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1(Mcl1), 5 ’ - CATTCTGGTAGAGCACCTAACACTTT-3 ’ (forward), and 5 ’-CATTTACAACCCACATTAACTTGCA-3 ’ (reverse); Bc12-like 1(Bc1211), 5 ’- CAGAGACTGACAGCCTGATGCT-3 ’(forward), and 5’ -ATTTCAAAGAGCTGGAACAAGTGTAG-3’(reverse).

The following primers were purchased from TAKARA BIO: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases (GAPDH), DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha (Gadd45a), apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1(Apaf1) and cyclin B2. Real-time quantitative PCRs were performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) or SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (TAKARA BIO). A comparative threshold cycle (CT) was used to determine gene expression relative to the control (calibrator). Hence, sample mRNA levels are expressed as n-fold differences relative to the calibrator. For each sample, the Mc11, Bcl2l1, Gadd45a, Apaf1 and cyclin B2 CT values were normalized using the formula ΔCT=CT taiget gene - CT target GAPDH. To determine the relative expression levels, the following formula was used: ΔΔCT=Δ CT (1) sample - CT(1) calibrator, and the value used to plot the relative target expression was calculated using the expression 2 −ΔΔCT.

Statistics

Comparisons were conducted on the real-time quantitative PCR analysis using a two-way analysis of variance, followed by Student’s t-test. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Pparα and related genes

In the Pparα-null mice, the PCR product of Pparα was not detected, whereas it was detected in the livers of wild-type mice as a 677bp amplicon (data not shown), suggesting knockout of the Pparα gene in the livers of Pparα-null mice. DEHP is known to up-regulate a gene encoding cytochrome P450, Cyp4a10, via PPARα15). To confirm that 0.05% DEHP activated the PPARα gene, the expression of Cyp4a10 mRNA was analyzed. In the livers of wild-type mice, 0.05% DEHP treatment up-regulated the Cyp4a10 (6.7-fold), compared to the control; no induction was found in the Pparα-null mice (data not shown). However, 0.05% DEHP did not affect the expression of the other PPARα-mediated genes such as acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 (Acox1), suggesting that this dose activated PPARα, albeit very weakly.

List of genes showing at least a 30-fold difference between adenoma and normal liver in wild-type and Pparα-null mice

In order to investigate the characteristic differences in the gene expression profiles of hepatocellular adenomas and normal tissues in wild-type or Pparα-null mice, genes that exhibited more than 30-fold differences in the microarray results were given more detailed consideration (Table 1). Although the microscopic phenotype changes were the same (hepatocellular adenomas) in both mouse lines, the gene expression profiles were quite different, and there were no changes which were common to wild-type and Pparα-null mice. The genes listed in Table 1 were then categorized by Simplified Gene Ontology as shown in the subheading (GO Biological Process), and there were no particular pathways which were altered. These results suggest that the tumorigenesis of hepatocellular adenomas in the wild-type mice may have a mechanism different from that in Pparα-null mice.

Table 1.

List of genes showing at least 30-fold difference between adenoma and normal liver in wild-type and Pparα-null mice

| Annotation | Gene symbol | Affymetrix ID | WT fold change |

Null fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell proliferation | ||||

| antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki 67 | Mki67 | 1426817_at | 6.97 | 56.34 |

| caveolin 2 | Cav2 | 1417327_at | 41.39 | 0.37 |

| discoidin domain receptor family, member 1 | Ddr1 | 1456226_x_at | 88.71 | 1.74 |

| Cell growth | ||||

| endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 | Esm1 | 1449280_at | 80.19 | 0.36 |

| Cell cycle | ||||

| growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 gamma | Gadd45g | 1453851_a_at | 0.02 | 19.49 |

| M phase phosphoprotein 6 | Mphosph6 | 1423848_at | 6.67 | 0.03 |

| polo-like kinase 3 (Drosophila) | Plk3 | 1434496_at | 11.22 | 30.19 |

| Cell death | ||||

| DNA-damage inducible transcript 3 | Ddit3 | 1417516_at | 31.63 | 1.24 |

| helicase, lymphoid specific | Hells | 1417541_at | 34.47 | 0.41 |

| insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 | Igfbp2 | 1454159_a_at | 0.03 | 1.18 |

| tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a | Tnfrsf12a | 1418571_at | 143.52 | 0.57 |

| tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a | Tnfrsf12a | 1418572_x_at | 237.36 | 0.88 |

| Transcription | ||||

| ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V0 subunit A1 | Atp6v0al | 1425227_a_at | 7.73 | 0.03 |

| bromodomain containing 8 | Brd8 | 1452350_at | 5.97 | 31.29 |

| RNA-binding region (RNP1, RRM) containing 2 | Rnpc2 | 1438398_at | 3.17 | 43.87 |

| Regulation of angiogenesis | ||||

| serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 1 | Serpine1 | 1419149_at | 144.33 | 1.03 |

| Cell adhesion | ||||

| cadherin 17 | Cdh17 | 1419331_at | 139.84 | 1.25 |

| camello-like 4 | Cml4 | 1419520_at | 0.02 | 0.45 |

| disabled homolog 1 (Drosophila) | Dab1 | 1421100_a_at | 51.82 | 0.07 |

| integrin alpha 6 | Itga6 | 1422444_at | 101.93 | 1.74 |

| integrin alpha 6 | Itga6 | 1422445_at | 263.27 | 0.12 |

| nidogen 1 | Nid1 | 1448469_at | 32.09 | 0.45 |

| protocadherin alpha 3 | Pcdha3 | 1420798_s_at | 45.77 | 2.28 |

| Cellular lipid metabolic process | ||||

| alpha fetoprotein | Afp | 1416645_a_at | 1701.20 | 1.60 |

| alpha fetoprotein | Afp | 1416646_at | 37.91 | 0.85 |

| alpha fetoprotein | Afp | 1436879_x_at | 668.50 | 25.39 |

| cytochrome P450, family 7, subfamily b, polypeptide 1 | Cyp7b1 | 1421075_s_at | 0.03 | 1.56 |

| elongation of very long chain fatty acids | Elovl3 | 1420722_at | 0.02 | 0.60 |

| (FEN1/Elo2, SUR4/Elo3, yeast)-like 3 | ||||

| glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, mitochondrial | Gpam | 1425834_a_at | 31.76 | 0.61 |

| hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3 beta- and steroid delta-isomerase 5 | Hsd3b5 | 1420531_at | 0.01 | 1.10 |

| Cellular metabolic process | ||||

| 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | Phgdh | 1426657_s_at | 277.81 | 3.05 |

| 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | Phgdh | 1437621_x_at | 140.56 | 10.57 |

| carboxypeptidase E | Cpe | 1415949_at | 60.52 | 0.37 |

| cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily a, polypeptide 2 | Cyp1a2 | 1450715_at | 0.02 | 1.58 |

| cytochrome P450, family 26, subfamily a, polypeptide 1 | Cyp26a1 | 1419430_at | 0.02 | 0.56 |

| glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase X-linked | G6pdx | 1422327_s_at | 41.99 | 0.69 |

| phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2 (mitochondrial) | Pck2 | 1425615_a_at | 43.62 | 1.30 |

| phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 | Psatl | 1451064_a_at | 238.29 | 0.75 |

| proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 4 | Pcsk4 | 1425824_a_at | 0.64 | 43.46 |

| serine peptidase inhibitor, Kazal type 3 | Spink3 | 1415938_at | 186.73 | 3.21 |

| stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase 2 | Scd2 | 1415822_at | 31.90 | 1.46 |

| sulfotransferase family IE, member 1 | Sult1e1 | 1420447_at | 0.03 | 2.67 |

| trimethyllysine hydroxylase, epsilon | Tmlhe | 1452500_at | 0.19 | 33.35 |

| Signal transduction | ||||

| LIM domain binding 1 | Ldb1 | 1452024_a_at | 38.99 | 9.08 |

| membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 4B | Ms4a4b | 1423467_at | 1.65 | 38.19 |

| met proto-oncogene | Met | 1422990_at | 88.36 | 0.09 |

| nischarin | Nisch | 1433757_a_at | 2.99 | 34.77 |

| regulator of G-protein signaling 16 | Rgs16 | 1426037_a_at | 39.07 | 36.22 |

| succinate receptor 1 | Sucnr1 | 1418804_at | 0.02 | 0.69 |

| Transport | ||||

| ATP-binding cassette, sub-family D (ALD), member 2 | Abcd2 | 1419748_at | 67.37 | 5.21 |

| EH-domain containing 2 | Ehd2 | 1427729_at | 0.22 | 46.20 |

| solute carrier family 25, member 24 | Slc25a24 | 1427483_at | 73.30 | 0.86 |

| solute carrier family 35, member A5 | Slc35a5 | 1419972_at | 0.23 | 37.53 |

| solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a1 | Slco1a1 | 1420379_at | 0.01 | 1.13 |

| solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a1 | Slcola1 | 1449844_at | 0.01 | 0.42 |

| Electron transport | ||||

| cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily f, polypeptide 16 | Cyp4f16 | 1430172_a_at | 34.00 | 1.07 |

| NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 | Ndufab1 | 1435934_at | 0.36 | 55.91 |

| alpha/beta subcomplex, 1 | ||||

| Inflammatory response | ||||

| chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 | Cxcl9 | 1418652_at | 229.56 | 14.44 |

| Immune system process | ||||

| histocompatibility 28 | H28 | 1425917_at | 37.13 | 1.68 |

| Immune system development | ||||

| lymphotoxin B | Ltb | 1419135_at | 227.86 | 5.44 |

| Immune response | ||||

| interleukin 18 binding protein | Il18bp | 1450424_a_at | 37.80 | 1.17 |

| Cell differentiation | ||||

| p21 (CDKN1A)-activated kinase 1 | Pak1 | 1450070_s_at | 37.23 | 3.81 |

| Translation | ||||

| ribosomal protein S24 | Rps24 | 1455195_at | 0.69 | 33.39 |

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid dioxygenase | Hpd | 1424618_at | 0.02 | 1.34 |

| brain glycogen phosphorylase | Pygb | 1433504_at | 30.64 | 1.58 |

| CD274 antigen | Cd274 | 1419714_at | 31.35 | 9.19 |

| coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain containing 6 | Chchd6 | 1438659_x_at | 1.61 | 140.90 |

| cytochrome P450, family 26, subfamily a, polypeptide 1 | Cyp26a1 | 1419430_at | 0.02 | 0.56 |

| cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 2 alpha | Ctla2a | 1448471_a_at | 5.29 | 36.13 |

| dedicator of cytokinesis 7 | Dock7 | 1425315_at | 0.03 | 20.73 |

| ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated-protein 10 | Gdap10 | 1420342_at | 0.39 | 41.03 |

| immediate early response 3 | Ier3 | 1419647_a_at | 54.23 | 1.00 |

| interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 | Ifit2 | 1418293_at | 346.68 | 0.43 |

| major urinary protein 1 | Mup1 | 1426154_s_at | 0.02 | 1.60 |

| Metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (non-coding RNA) | Malat1 | 1418188_a_at | 0.75 | 33.73 |

| Metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (non-coding RNA) | Malat1 | 1418189_s_at | 0.71 | 33.07 |

| niban protein | Niban | 1422567_at | 83.17 | 5.39 |

| nuclear protein 1 | Nupr1 | 1419666_x_at | 54.16 | 2.72 |

| orosomucoid 3 | Orm3 | 1450611_at | 0.01 | 0.46 |

| pannexin 1 | Panx1 | 1416379_at | 50.37 | 2.19 |

| per-pentamer repeat gene | Ppnr | 1420747_at | 0.73 | 52.00 |

| proline-rich nuclear receptor coactivator 1 | Pnrc1 | 1438524_x_at | 82.30 | 2.59 |

| Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, alpha type 6 | Psma6 | 1435316_at | 9.90 | 40.91 |

| ras homolog gene family, member C | Rhoc | 1448605_at | 45.61 | 1.68 |

| restin | Rsn | 1425060_s_at | 0.03 | 34.83 |

| ROD1 regulator of differentiation 1 (S. pombe) | Rod1 | 1424084_at | 15.84 | 51.59 |

| similar to transcription factor SOX-4 | LOC672274 | 1433575_at | 35.37 | 1.03 |

| telomeric repeat binding factor 1 | Terf1 | 1418380_at | 37.79 | 2.64 |

| tetraspanin 8 | Tspan8 | 1424649_a_at | 1489.50 | 2.77 |

| tetratricopeptide repeat domain 14 | Ttc14 | 1426544_a_at | 0.82 | 112.05 |

| tubulin, beta 2b | Tubb2b | 1449682_s_at | 41.89 | 2.29 |

| Z-DNA binding protein 1 | Zbp1 | 1429947_a_at | 37.19 | 1.63 |

Data are expressed as the ratio of gene expression to those of respective normal liver exposed to 0.01% DEHP in WT and 0.05% in Null (respective normal level=1). WT, hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice; Null, hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice (n=1).

Carcinogenesis-related genes

Alteration of particular pathways related to adenoma formation was not identified in the overall gene expression profiles in the hepatocellular adenoma tissues of both wild-type and Pparα-null mice when judged by analysis of those genes yielding 30-fold changes. Therefore, the expression levels of carcinogenesis-related genes were inspected (Table 2). Carcinogenesis-related genes were selected according to GeneSpring’s gene category, carcinogenesis and tumor suppressor genes. Surprisingly, the expression profiles of these genes were quite different between wild-type and .Pparα-null mice.

Table 2.

Carcinogenesis-related genes

| Annotation | Gene symbol | Affymetrix ID | WT fold change |

Null fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcinogenesis | ||||

| met proto-oncogene | Met | 1422990_at | 88.36 | 0.09 |

| RAB34, member of RAS oncogene family | Rab34 | 1416590_a_at | 5.06 | 0.16 |

| ect2 oncogene | Ect2 | 1419513_a_at | 3.63 | 0.27 |

| v-ral simian leukemia viral oncogene homolog A (ras related) | Rala | 1450870_at | 2.41 | 0.41 |

| thymoma viral proto-oncogene 1 | Akt1 | 1425711_a_at | 2.28 | 0.24 |

| v-crk sarcoma virus CT10 oncogene homolog (avian)-like | Crk1 | 1421954_at | 15.80 | 0.55 |

| RAB3D, member RAS oncogene family | Rab3d | 1418890_a_at | 6.07 | 0.70 |

| E26 avian leukemia oncogene 2, 3' domain | Ets2 | 1416268_at | 3.59 | 0.89 |

| Rab38, member of RAS oncogene family | Rab38 | 1417700_at | 2.92 | 0.82 |

| RAB3D, member RAS oncogene family | Rab3d | 1418891_a_at | 2.89 | 0.71 |

| RAB6, member RAS oncogene family | Rab6 | 1448305_at | 2.41 | 0.88 |

| RAB1, member RAS oncogene family | Rab1 | 1416082_at | 2.26 | 0.94 |

| N-acetylglucosamine-1 -phosphate transferase, alpha and beta subunits | Gnptab | 1435335_a_at | 2.24 | 0.83 |

| RAB2, member RAS oncogene family | Rab2 | 1418622_at | 2.17 | 0.90 |

| avian reticuloendotheliosis viral (v-rel) oncogene-related B | Relb | 1417856_at | 2.14 | 0.69 |

| RAN, member RAS oncogene family | Ran | 1438977_x_at | 2.13 | 0.83 |

| related RAS viral (r-ras) oncogene homolog 2 | Rras2 | 1417398_at | 1.97 | 0.50 |

| RAB18, member RAS oncogene family | Rab18 | 1420899_at | 1.96 | 0.23 |

| similar to Yamaguchi sarcoma viral (v-yes-1) oncogene homolog | LOC676654 | 1425598_a_at | 1.80 | 0.43 |

| v-crk sarcoma virus CT10 oncogene homolog (avian) | Crk | 1425855_a_at | 1.18 | 0.42 |

| feline sarcoma oncogene | Fes | 1427368_x_at | 1.06 | 3.34 |

| myelocytomatosis oncogene | Myc | 1424942_a_at | 1.02 | 2.62 |

| feline sarcoma oncogene | Fes | 1452410_a_at | 0.86 | 2.84 |

| Fyn proto-oncogene | Fyn | 1417558_at | 0.81 | 2.01 |

| RAB 14, member RAS oncogene family | Rab14 | 1441992_at | 0.81 | 4.73 |

| ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator-like 2 | Rgl2 | 1450688_at | 0.79 | 3.76 |

| ELK4, member of ETS oncogene family | Elk4 | 1427162_a_at | 0.72 | 2.14 |

| E26 avian leukemia oncogene 1,5’ domain | Ets1 | 1422028_a_at | 0.70 | 2.56 |

| v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family, protein G (avian) | Mafg | 1448916_at | 0.68 | 2.77 |

| RAB22A, member RAS oncogene family | Rab22a | 1424504_at | 0.57 | 2.57 |

| v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family, protein B (avian) | Mafb | 1451716_at | 0.26 | 3.49 |

| v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family, protein B (avian) | Mafb | 1451715 _at | 0.09 | 6.86 |

| colony stimulating factor 1 receptor | Csf1r | 1419872_at | 0.46 | 1.44 |

| RAB, member of RAS oncogene family-like 4 | Rabl4 | 1435736_x_at | 0.45 | 1.70 |

| c-mer proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase | Mertk | 1422869_at | 0.43 | 1.46 |

| colony stimulating factor 1 receptor | Csf1r | 1419873_s_at | 0.41 | 1.32 |

| Tumor supressor | ||||

| suppression of tumorigenicity 14 (colon carcinoma) | St14 | 1418076_at | 2.79 | 0.36 |

| large tumor suppressor | Lats1 | 1427679_at | 2.53 | 0.32 |

| tumor suppressor candidate 3 | Tusc3 | 1421662_a_at | 4.42 | 0.57 |

| retinoblastoma-like 1 (p107) | Rbl1 | 1424156_at | 3.26 | 0.79 |

| suppression of tumorigenicity 13 | St13 | 1460193_at | 2.33 | 0.86 |

| tumor suppressing subtransferable candidate 1 | Tssc1 | 1436955_at | 1.51 | 0.43 |

| MAD homolog 4 (Drosophila) | Smad4 | 1422486_a_at | 0.74 | 2.33 |

| large tumor suppressor 2 | Lats2 | 1425420_s_at | 0.13 | 1.94 |

Genes up-regulated in at least 2-fold changes are in black, and those down-regulated at least 2-fold changes are in gray. Data are expressed as the ratio of gene expression to those of respective normal liver exposed to 0.01% DEHP in WT and 0.05% DEHP in Null (respective normal level=1). WT, hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice; Null, hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice (n=1).

The expressions of the met proto-oncogene (Met) and v-crk sarcoma vims CT10 oncogene homolog (avian)-like (Crkl) were increased only in adenoma tissue of wild-type mice. Expression of v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family, protein B (avian) (Mafb) were decreased in that of wild-type mice, but increased in Pparα-null mice. Most tumor suppressor genes were increased in tumor tissue of wild-type mice, but decreased in that of Pparα-null mice. Only MAD homolog 4 (Smad4) was decreased in tumor tissue of wild-type mice, but increased in that of Pparα-null mice. These results suggest that decreased expression of tumor suppressor genes may be related to the increased tumorigenesis in Pparα-null mice exposed to DEHP.

G2/M phase-related genes

The cell cycle is regulated by cyclins and cyclin-dependent protein kinases, which play an important role in cell growth control16,17). The microarray data of carcinogenicity-related genes did not reveal any typical profiles in either mouse line. Since the expressions of cyclin B1 (Ccnb1) and cyclin B2 (Ccnb2) were up-regulated in tumor tissue of Pparα-null mice, G2/M phase-related genes were explored in more depth (Table 3). Myelin transcription factor 1(Myt1) was down-regulated in tumor tissue of Pparα-null mice, but not in that of wild-type mice. In contrast, the induction levels of cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (Cdk7), growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha (Gadd45a) in tumor tissue of wild-type mice were higher than those in Pparα-null mice.

Table 3.

G2/M cell cycle-related genes

| Gene name | Gene symbol | Affymetrix ID | WT adenoma |

Null adenoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell division cycle 2 homolog A | Cdc2a | 1448314_at | 6.12 | 2.39 |

| Cell division cycle 25 homolog B | Cdc25b | 1421963_a_at | 0.63 | 1.35 |

| Checkpoint kinase 1 homolog | Chek1 | 1450677_at | 0.13 | 0.20 |

| Checkpoint kinase 2 homolog | Chek2 | 1422747_at | 0.76 | 0.43 |

| Cyclin B1 | Ccnb1 | 1448205_at | 1.51 | 3.38 |

| Cyclin B2 | Ccnb2 | 1450920_at | 4.23 | 13.03 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 7 | Cdk7 | 1451741_a_at | 5.21 | 0.46 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (P21) | Cdkn1a | 1421679_a_at | 1.11 | 0.56 |

| Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha | Gadd45a | 1449519_at | 7.09 | 0.78 |

| Myelin transcription factor 1 | Myt1 | 1422773_at | 0.94 | 0.31 |

| Transformation related protein 53 | Trp53 | 1427739_a_at | 1.64 | 1.80 |

Data are expressed as the ratio of gene expression to those of respective normal liver exposed to 0.01% DEHP in WT and 0.05% DEHP in Null (respective normal level=1). WT, hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice; Null, hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice (n=1).

Caspase 3-dependent apoptosis pathway-related genes

Apoptosis is executed via multiple pathways, all involving caspase activation18). Caspase 3-dependent apoptosis pathway-related genes were explored in depth. Table 4 shows expression levels of caspase 3-dependent apoptosis pathway-related genes. The expression level of myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1(Mcl1) in adenoma tissue of Pparα-null mice was higher than that of wild-type mice. In contrast, expression levels of apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1(Apaf1) and caspase 3 in tumor tissue of wild-type mice were higher than in Pparα-null mice.

Table 4.

Caspase3-dependent apoptosis-related genes

| Gene name | Gene symbol | Affymetrix ID | WT adenoma |

Null adenoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 | Apaf1 | 1450223_at | 1.32 | 0.23 |

| Bc12-like 1 | Bcl2l1 | 1420888_at | 0.76 | 1.53 |

| Caspase-3 | Casp3 | 1426165_a_at | 1.48 | 0.44 |

| Caspase-9 | Casp9 | 1437537_at | 0.50 | 1.53 |

| Cytochrome c | Cycs | 1422484_at | 0.72 | 1.00 |

| myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 | Mcl1 | 1456381_x_at | 0.92 | 3.73 |

| myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 | Mcl1 | 1456243_x_at | 1.66 | 2.63 |

Data are expressed as the ratio of gene expression to those of respective normal liver exposed to 0.01% DEHP in WT and 0.05% DEHP in Null (respective normal level=1). WT, hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice; Null, hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice (n=1).

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

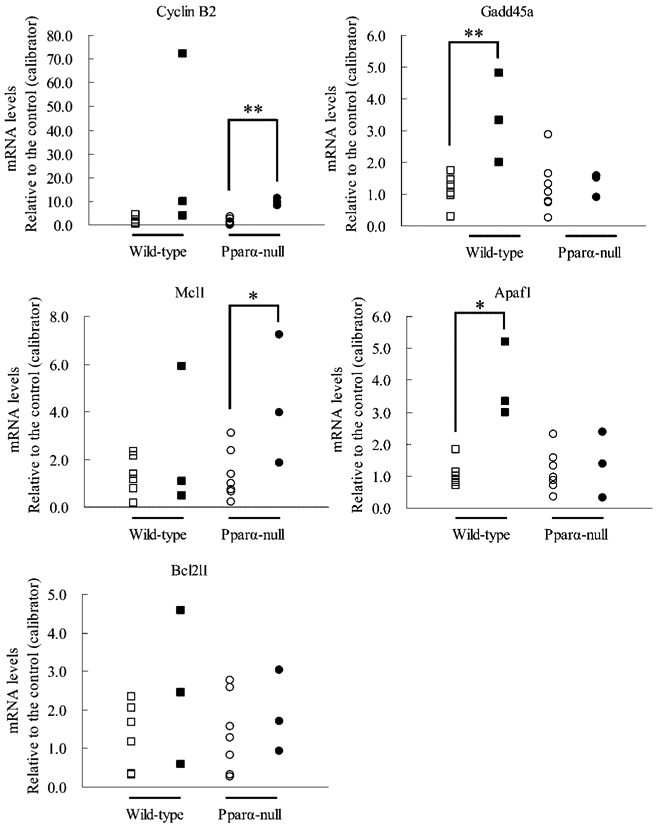

The expressions of two mRNAs related to control of the G2/M cell cycle, cyclin B2 and Gadd45a mRNA, were measured using real-time quantitative PCR analysis (Fig. 1). Expression of cyclin B2 mRNA was significantly up-regulated in tumor tissues of Pparα-null mice compared to the normal tissues of control mice with the same genetic background, and up-regulated in those of wild-type mice; in particular, one tumor revealed a 72-fold up-regulation. The expression of Gadd45a mRNA was significantly up-regulated in tumor tissues of wild-type mice compared to normal tissues of control mice, but not in the tumor tissues of Pparα-null mice.

Fig. 1.

mRNA levels of cyclin B2, Gadd45a, Mcl1, Apaf1 and Bcl2l1 in wild-type mice livers with adenoma. mRNA levels of GAPDH mRNA, cyclin B2, Gadd45a, Mcl1, Apaf1 and Bcl2l1 were measured by real-time quantitative PCR method in normal livers (n=7) of control and hepatocellular adenoma tissues (n=3) of wild-type or Pparα-null mice exposed to 0, 0.01 or 0.05% DEHP. mRNA levels of each gene were normalized to those of GAPDH mRNA, and were expressed as an n-fold differences. Open and closed rectangles, normal liver and hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice exposed to 0 and DEHP, respectively; open and closed circles, normal liver and hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice exposed to 0 and DEHP. *Significant difference between normal and tumor tissues, p<0.05. **Significant difference between normal and tumor tissues, p<0.01.

Next, the expression of three apoptosis pathway genes, Mcl1, Apaf1, and Bcl2l1 mRNA, were also measured using the same method. In tumor tissues of Pparα-null mice, the expression of Mcl1 mRNA was significantly up-regulated compared to normal tissues of control mice with the same genetic background. In contrast, expression was down-regulated in tumor tissues of two wild-type mice, and no difference was observed in expression in wild-type mice. The expression of Apaf1 mRNA was significantly up-regulated in the tumor tissues of wild-type mice compared to normal tissues of the control group. On the contrary, there was no significant difference in the expression of these genes in Pparα-null mice. The expression of Bcl2l1 mRNA was not significantly changed between tumor and normal tissues of both Pparα-null and wild-type mice.

Discussion

Differences in tumorigenesis of relatively low-dose DEHP-induced hepatocellular adenomas between Pparα-null and wild-type mice were clearly elucidated in the current study using microarray and real-time quantitative PCR analyses. These findings suggest that DEHP-induced hepatocellular adenoma in Pparα-null mice was caused by enhanced progression at the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint and suppression of apoptosis through caspase signaling. In wild-type mice, however, these pathways might not be involved, suggesting that DEHP-induced tumorigenesis is different in the two genotyped mice.

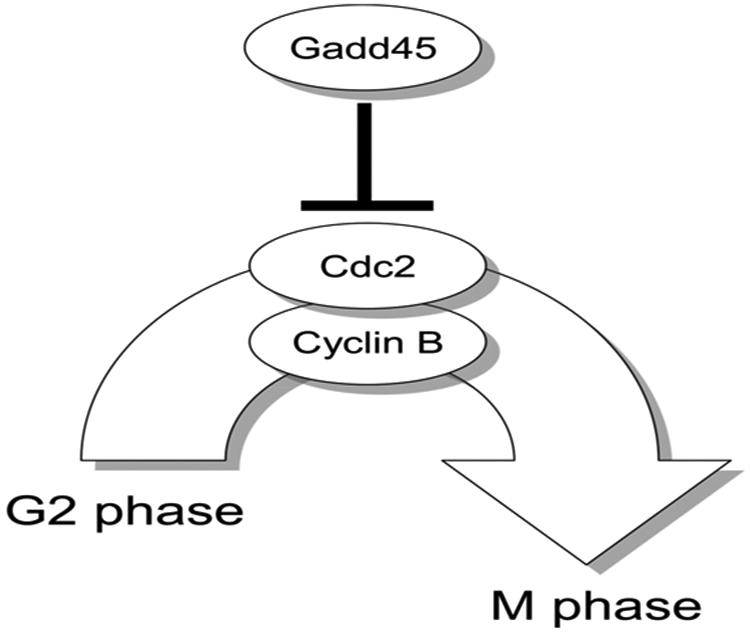

Cyclin B and cyclin D play a central role in cell cycle regulation19-23). From the microarray data in genes encoding G2/M cell cycle phase proteins, cyclin B was increased in hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice. cyclin B forms a complex with Cdc2, which is activated by dephosphorylation, and a dephosphorylated complex triggers mitosis20,22). Gadd45 inhibits mitosis and promotes G2/M arrest24, 25). Our findings that the expression of Gadd45a was increased in the hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice, but not in those of Pparα-null mice, suggest that activation of Cdc2/cyclin B complex was not inhibited by Gadd45a, and that hepatocyte mitosis was promoted in the tumor tissues of Pparα-null mice. However, in the tumor tissues of wild-type mice, increased Gadd45a might inhibit the activation of the Cdc2/cyclin B complex, and mitosis of hepatocyte cells might not be promoted in the tumor tissues. From the microarray data, Myt1 and p21/cip, which inhibit mitosis as well as Gadd45a, appeared to be down-regulated only in the hepatocellular adenoma tissue of Pparα-null mice. Moreover, Cdc25b, which also promotes M-phase entry, tended to be elevated in hepatocellular adenoma tissue of Pparα-null mice. These results suggest that the changes in the expression of Myt1, p21/cip and Cdc25b genes might also be related to control of the cell cycle G2/M checkpoint and enhance cell proliferation in the tumor tissues of Pparα-null mice, though these gene expressions were not reconfirmed by real-time quantitative PCR analysis. Other factors also regulate the cell cycle. Since CDK7, which promotes mitosis, increased in hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice, but not in those of Pparα-null mice, cell proliferation in wild-type mice might partly be related to an increase in CDK7. Taken together, although cell proliferation due to enhanced mitosis may occur in the hepatocellular adenoma tissues of both mouse lines, their signaling pathways may differ.

Why cell cycle regulation was different in hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null and those of wild-type mice could not be resolved in this study. In a previous study, PPARα suppressed DEHP-induced oxidative stress: 8-oxoguanidine (8-OHdG) levels due to DEHP exposure were higher in the livers of Pparα-null mice than those of wild-type mice, suggesting that DNA damage is induced in the livers of Pparα-null mice12). Nevertheless, DEHP treatment did not induce, and even appeared to down-regulate, Gadd45a in the livers of Pparα-null mice, suggesting an enhancement of the surroundings for hepatic tumorigenesis in these mice. Intraperitoneal injection of 2-nitropropane, an oxidative stress inducing agent, increased 8-OHdG levels in mouse liver tissues and also increased the p53 protein level26). The p53 protein is involved in DNA repair by recruiting reaper protein such as Gadd4527). However, there was no significant difference in up-regulation of p53 between tumor tissues of wild-type and Pparα-null mice in the current experiment (data not shown).

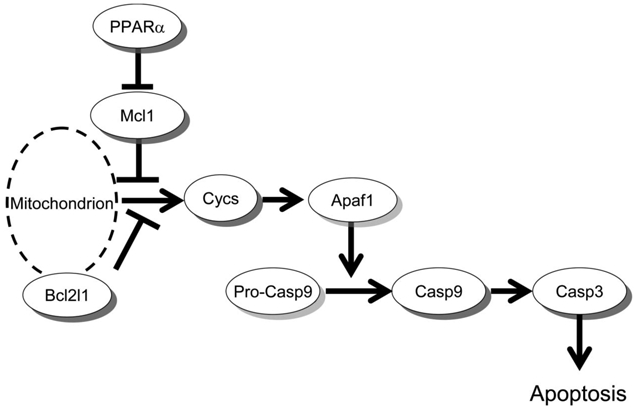

The mitochondrial apoptotic pathway initiates the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. Cytochrome c activates Apaf1 protein, which in turn activates caspase 9, resulting in caspase 3-dependent cell death28-30). Apaf1 mRNA was induced only in hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice, but not in those of Pparα-null mice. In addition, caspase 3 was increased 2.4-fold in adenoma tissues of wild-type mice, but not in those of Pparα-null mice, though the activity was not measured in this experiment. These results suggest that DEHP might suppress apoptosis due to an inactivation event downstream of caspase only in hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice. On the other hand, DEHP up-regulated Mcl1 expression only in the tumor tissues of Pparα-null mice. Mcl1, a member of the Bcl-2 family, strongly inhibits tBid-induced cytochrome c release31), and delays apoptosis induced by c-Myc overexpression in Chinese hamster ovary cells32) and hematopoietic cells33). Short-term treatment of mice with Wy-14,643 significantly decreased the levels of anti-apoptotic Mcl1 transcript and protein in wild-type mice, but not in Pparα-null mice34), suggesting the involvement of PPARα in Mcl1 expression. Since the dose of DEHP used in this experiment was relatively low and activated PPARα very weakly, the effect on Mcl1 might not have been observable in the wild-type mice. However, increased Mcl1 in the hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice might suppress the release of cytochrome c, which may also be involved in the suppression of caspase 3-dependent apoptosis. On the other hand, expression of Bcl2l1, which also inhibits cytochrome c release as well as Mcl1, did not differ in hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null and wild-type mice treated with DEHP.

Of the carcinogenesis-related genes selected according to GeneSpring’s gene category, 16 and 12 genes were up-regulated in liver adenoma tissue of wild-type and Pparα-null mice, respectively. However, expression levels of these genes did not change or were somewhat down-regulated in the liver tissue of Pparα-null and wild-type mice, respectively. In contrast, 5 and 1 of the expression levels of tumor suppressor genes were up-regulated in liver adenoma tissue of wild-type and Pparα-null mice, respectively. It is striking that up- or down-regulation of these carcinogenesis-related genes was starkly inconsistent with the two genotype mice. Although these results were obtained from microarray analysis using only one tissue of normal and adenoma in wild-type and Pparα-null mice, the gene expression differences of these genes in the two genotype mice may explain the different mechanisms of DEHP-induced tumorigenesis observed in wild-type and Pparα-null mice. Met is overexpressed in a variety of malignancies35) and thought to be a proto-oncogene. The expression level of Met was notably increased (88-fold) in liver adenoma tissue in wild-type mice, which may suggest the involvement of Met in DEHP-induced tumorigenesis in wild-type mice.

In this study, data obtained using microarray showed correspondence with those from real-time quantitative PCR. We handled tissues of hepatocellular adenomas obtained from two doses, 0.01 and 0.05% DEHP treatment, as samples of adenoma tissues, and analyzed them together. However, this handling did not affect data interpretation, because data obtained from RT quantitative PCR showed phenotype-, not dose-related results.

The incidence of spontaneous liver tumors in mice is rare in all strains before 12 months of age and then increases with age36). Frequency and liver tumor type depend on strain and sex37). We assume that liver tumors in Pparα-null mice resulted from DEHP exposure, because the frequencies in the DEHP-treated group were higher than in the control group. However, we could not determine whether DEHP promoted the spontaneous liver tumor in Pparα-null mice, because spontaneous hepatocellular tumors are known to occur in these mice at 24 months of age38). Thus, the mechanisms of spontaneous tumorigenesis may be different between Pparα-null and wild-type mice. To clarify this, gene expression profiles of liver tumors in the control group need to be analyzed.

Since neither the number of mice used in each group nor the DEHP concentrations were very high in this experiment, the samples for analyzing tumorigenesis of hepatocellular adenomas induced by DEHP were limited. In addition, we only analyzed mRNA expressions of many genes using microarray and in part real-time quantitative PCR analyses. To reconfirm the different tumorigenesis of DEHP between wild-type and Pparα-null mice reported in this manuscript, further studies are needed with an increase in animal numbers or DEHP exposure concentration, and analysis by immunohistochemical staining and/or western blot of the important genes such as Gadd45a and Apaf1, and caspase 3 activity. The results of such studies may uncover a new mechanism of tumorigenesis which is induced by DEHP.

In summary, tumorigenesis of low-dose DEHP-induced liver adenoma in Pparα-null mice might be different from that of wild-type mice, possibly involving suppression of G2/M arrest in the former which might be caused by inhibition of Gadd45a and inhibition of caspase 3-dependent apoptosis. Thus, several mechanisms of tumorigenesis of hepatocellular adenomas could be triggered by DEHP exposure in mice.

Fig. 2.

G2/M arrest regulated by Gadd45. Gadd45 protein interacts with Cdc2-cyclin B complexes and promotes G2/M arrest. Since Gadd45 in the hepatocellular adenoma tissues of wild-type mice was induced by DEHP exposure, but not in those of Pparα-null mice, the promotion of the arrest might not have occurred in the Pparα-null mice, but may have been in the wild-type mice.

Fig. 3.

Apoptosis pathway diagram via caspase 3. Since expression of Mcl1 was increased only in the hepatocellular adenoma tissues of Pparα-null mice exposed to DEHP, while expression of Apaf1 was induced only in those of wild-type mice, apoptosis via caspase 3 might be inhibited in the Pparα-null mice, but not in the wild-type mice.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Prof. Yoshimitsu Fukushima, Department of Preventive Medicine, Shinshu University School of Medicine, and Dr. Toshikazu Miyagishima, Dr. Toshihiko Kasahara, and Dr. Naoki Toritsuka for assistance with the microarray studies, and Dr. Junji Kuroda and Dr. Makoto Murakami for their cooperation in performing these studies. This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid (No. B 14370121, 17390169) for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

References

- 1).Huber WW, Grasl-Kraupp B and Schulte-Hermann R: Hepatocarcinogenic potential of di (2-Ethelhexyl) phthalate in rodents and its implications on human risk. Cnt Rev Toxicol 26, 365–481 (1996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Some industrial chemicals IARC monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans 77. Lyon: IARC, 2000: 41–148. [Google Scholar]

- 3).Corton JC, Anderson SP and Stauber A: Central role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in the actions of peroxisome proliferators. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 40, 491–518 (2000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Peters JM, Cattley RC and Gonzalez FJ: Role of PPAR alpha in the mechanism of action of the nongenotoxic carcinogen and peroxisome proliferator Wy-14,643. Carcinogenesis 18, 2029–2033 (1997) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Ashby J, Brady A, Elcombe CR, Elliott BM, Ishmael J, Odum J, Tugwood JD, Kettle S and Purchase IF: Mechanistically-based human hazard assessment of peroxisome proliferator-induced hepatocarcinogenesis. Hum Exp Toxicol 13, S1–S117 (1994) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Bursch W, Lauer B, Timmermann-Trosiener I, Barthel G, Schuppler J and Schulte-Hermann R: Controlled death (apoptosis) of normal and putative preneoplastic cells in rat liver following withdrawal of tumor promoters. Carcinogenesis 5, 453–458 (1984) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Marsman DS, Goldsworthy TL and Popp JA: Contrasting hepatocytic peroxisome proliferation, lipofuscin accumulation and cell turnover for the hepatocarcinogens Wy-14,643 and clofibric acid. Carcinogenesis 13, 1011–1017 (1992) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Peters JM, Aoyama T, Cattley RC, Nobumitsu U, Hashimoto T and Gonzalez FJ: Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in altered cell cycle regulation in mouse liver. Carcinogenesis 19, 1989–1994 (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Bayly AC, Roberts RA and Dive C: Suppression of liver cell apoptosis in vitro by the non-genotoxic hepatocarcinogen and peroxisome proliferator nafenopin. J Cell Biol 125, 197–203 (1994) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Gill JH, James NH, Roberts RA and Dive C: The non-genotoxic hepatocarcinogen nafenopin suppresses rodent hepatocyte apoptosis induced by TGFbeta1, DNA damage and Fas. Carcinogenesis 19, 299–304 (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Shah YM, Morimura K, Yang Q, Tanabe T, Takagi M and Gonzalez FJ: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha regulates a microRNA-mediated signaling cascade responsible for hepatocellular proliferation. Mol Cell Biol 27, 4238–4247 (2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Ito Y, Yamanoshita O, Asaeda N, Tagawa Y, Lee CH, Aoyama T, Ichihara G, Furuhashi K, Kamijima M, Gonzalez FJ and Nakajima T: Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate induces hepatic tumorigenesis through a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-independent pathway. J Occup Health 49, 172–182 (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Lee SS, Pineau T, Drago J, Lee EJ, Owens JW, Kroetz DL, Fernandez-Salguero PM, Westphal H and Gonzalez FJ: Targeted disruption of the alpha isoform of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene in mice results in abolishment of the pleiotropic effects of peroxisome proliferators. Mol Cell Biol 15, 3012–3022 (1995) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Lamb JC 4th, Chapin RE, Teague J, Lawton AD and Reel JR: Reproductive effects of four phthalic acid esters in the mouse. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 88, 255–269 (1987) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Richert L, Lamboley C, Viollon-Abadie C, Grass P, Hartmann N, Laurent S, Heyd B, Mantion G, Chibout SD and Staedtler F: Effects of clofibric acid on mRNA expression profiles in primary cultures of rat, mouse and human hepatocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 191, 130–146 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Arellano M and Moreno S: Regulation of CDK/cyclin complexes during the cell cycle. Int Biochem Cell Biol 29, 559–573 (1997) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Sherr CJ: Mammalian G1 cyclins. Cell 73, 1059–1065 (1993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Wesche-Soldato DE, Swan RZ, Chung CS and Ayala A: The apoptotic pathway as a therapeutic target in sepsis. Curr Drug Targets 8, 493–500 (2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Kato J, Matsushime H, Hiebert SW, Ewen ME and Sherr CJ: Direct binding of cyclin D to the retinoblastoma gene product (pRb) and pRb phosphorylation by the cyclin D-dependent kinase CDK4. Genes Dev 7, 331–342 (1993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Lew DJ and Kornbluth S: Regulatory roles of cyclin dependent kinase phosphorylation in cell cycle control. Curr Opin Cell Biol 8, 795–804 (1996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Lundberg AS and Weinberg RA: Functional inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein requires sequential modification by at least two distinct cyclin-cdk complexes. Mol Cell Biol 18, 753–761 (1998) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Solomon MJ, Glotzer M, Lee TH, Philippe M and Kirschner MW: Cyclin activation of p34cdc2. Cell 63, 1013–1024 (1990) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Weinberg RA: The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell 81, 323–330 (1995) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Maeda T, Hanna AN, Sim AB, Chua PP, Chong MT and Tron VA: GADD45 regulates G2/M arrest, DNA repair, and cell death in keratinocytes following ultraviolet exposure. J Invest Dermatol 119, 22–26 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Zhan Q, Antinore MJ, Wang XW, Carrier F, Smith ML, Harris CC and Fornace AJ Jr: Association with Cdc2 and inhibition of Cdc2/Cyclin B1 kinase activity by the p53-regulated protein Gadd45. Oncogene 18, 2892–2900 (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Cabelof DC, Raffoul JJ, Yanamadala S, Guo Z and Heydari AR: Induction of DNA polymerase beta-dependent base excision repair in response to oxidative stress in vivo. Carcinogenesis 23, 1419–1425 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Kastan MB, Zhan Q, el-Deiry WS, Carrier F, Jacks T, Walsh WV, Plunkett BS, Vogelstein B and Fornace AJ Jr.: A mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway utilizing p53 and GADD45 is defective in ataxia-telangiectasia. Cell 71, 587–597 (1992) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Bossy-Wetzel E and Green DR: Apoptosis: checkpoint at the mitochondrial frontier. Mutat Res 434, 243–251 (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Budihardjo I, Oliver H, Lutter M, Luo X and Wang X: Biochemical pathways of caspase activation during apoptosis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 15, 269–290 (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Cecconi F: Apaf1 and the apoptotic machinery. Cell Death Differ 6, 1087–1098 (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Clohessy JG, Zhuang J, de Boer J, Gil-Gómez G and Brady HJ: Mcl-1 interacts with truncated Bid and inhibits its induction of cytochrome c release and its role in receptor-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem 281, 5750–5759 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Reynolds JE, Yang T, Qian L, Jenkinson JD, Zhou P, Eastman A and Craig RW: Mcl-1, a member of the Bcl-2 family, delays apoptosis induced by c-Myc overexpression in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cancer Res 54, 6348–6352 (1994) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Zhou P, Qian L, Kozopas KM and Craig RW: Mcl-1, a Bcl-2 family member, delays the death of hematopoietic cells under a variety of apoptosis-inducing conditions. Blood 89, 630–643 (1997) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Xiao S, Anderson SP, Swanson C, Bahnemann R, Voss KA, Stauber AJ and Corton JC: Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha enhances apoptosis in the mouse liver. Toxicol Sci 92, 368–377 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Sattler M and Salgia R: c-Met and hepatocyte growth factor: potential as novel targets in cancer therapy. Curr Oncol Rep 9, 102–108 (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Frith CH and Wiley L: Spontaneous hepatocellular neoplasms and hepatic hemangiosarcomas in several strains of mice. Lab Anim Sci 32, 157–162 (1982) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Nakamura K, Kuramoto K, Shibasaki K, Shumiya S and Ohtsubo K: Age-related incidence of spontaneous tumors in SPF C57BL/6 and BDF1 mice. Jikken Dobutsu 41, 279–285 (1992) (in Japanese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Howroyd P, Swanson C, Dunn C, Cattley RC and Corton JC: Decreased longevity and enhancement of age-dependent lesions in mice lacking the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha). Toxicol Pathol 32, 591–599 (2004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]