Significance Statement

Use of cold storage for organ preservation in kidney transplantation is associated with cold ischemia-reperfusion injury that contributes to delayed graft function and affects the long-term outcome of transplanted kidneys. Using rat proximal tubule cells and a mouse model, the authors demonstrated that protein kinase C-δ (PKCδ), which is implicated in ischemia-reperfusion injury in other organs, is activated in tubular cells during cold storage–associated transplantation and accumulates in mitochondria. There, it mediates phosphorylation of a mitochondrial fission protein, dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), at serine 616. Drp1 activation leads to mitochondrial fragmentation, accompanied by mitochondrial damage and kidney tubular cell death. Genetic ablation (in PKCδ-knockout mice) or use of a peptide inhibitor of PKCδ reduced kidney injury in cold storage–associated transplantation, pointing to PKCδ as a promising therapeutic target for kidney transplant.

Keywords: transplantation, mitochondria, PKCδ; kidney, ischemia-reperfusion

Abstract

Background

Kidney injury associated with cold storage is a determinant of delayed graft function and the long-term outcome of transplanted kidneys, but the underlying mechanism remains elusive. We previously reported a role of protein kinase C-δ (PKCδ) in renal tubular injury during cisplatin nephrotoxicity and albumin-associated kidney injury, but whether PKCδ is involved in ischemic or transplantation-associated kidney injury is unknown.

Methods

To investigate PKCδ’s potential role in injury during cold storage–associated transplantation, we incubated rat kidney proximal tubule cells in University of Wisconsin (UW) solution at 4°C for cold storage, returning them to normal culture medium at 37°C for rewarming. We also stored kidneys from donor mice in cold UW solution for various durations, followed by transplantation into syngeneic recipient mice.

Results

We observed PKCδ activation in both in vitro and in vivo models of cold-storage rewarming or transplantation. In the mouse model, PKCδ was activated and accumulated in mitochondria, where it mediated phosphorylation of a mitochondrial fission protein, dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), at serine 616. Drp1 activation resulted in mitochondrial fission or fragmentation, accompanied by mitochondrial damage and tubular cell death. Deficiency of PKCδ in donor kidney ameliorated Drp1 phosphorylation, mitochondrial damage, tubular cell death, and kidney injury during cold storage–associated transplantation. PKCδ deficiency also improved the repair and function of the renal graft as a life-supporting kidney. An inhibitor of PKCδ, δV1-1, protected kidneys against cold storage–associated transplantation injury.

Conclusions

These results indicate that PKCδ is a key mediator of mitochondrial damage and renal tubular injury in cold storage–associated transplantation and may be an effective therapeutic target for improving renal transplant outcomes.

Kidney transplantation offers the best form of RRT for the patients with ESKD, leading to improved quality of life and survival. Consequently, the demand for kidney transplantation has grown rapidly and has overwhelmingly exceeded the available supply of organs.1,2 The kidneys for transplantation are from either living or deceased donors. Although the kidneys from living donors are known to have a better long-term outcome, the majority of transplanted kidneys are from deceased donors. Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) or ischemic AKI is an inevitable consequence of transplantation of the kidneys from deceased donors due to cold storage for procurement, tissue typing, and transportation before transplantation occurs. Kidney injury due to cold storage–associated transplantation is known to be a major cause of delayed graft function and a potential contributor of chronic allograft nephropathy.1,3,4

Transplanted kidneys usually undergo several episodes of ischemia, including cold ischemia during organ storage in preservation solutions as well as warm ischemia during organ harvesting and transplantation surgeries.1,4 Under these conditions, dysfunction and the loss of renal proximal tubular cells play a critical role in the pathogenesis of AKI, responsible for deteriorated renal function and structural damage.4–7 The mechanism of proximal tubular cell injury and death in AKI is complex, but it includes mitochondrial damage.8–10 In particular, there is an early disruption of mitochondrial dynamics in ischemic AKI, resulting in mitochondrial fragmentation that contributes to proximal tubular cell injury and death.11–13 The disruption of mitochondrial dynamics has been demonstrated in other types of kidney injury.12,14,15 In a rat model of kidney cold storage–associated transplantation, Parajuli et al.16 demonstrated the loss of mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins, which is associated with mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction. Nonetheless, the role and regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in kidney transplantation remains largely unclear.

Protein kinase C-δ (PKCδ) is a member of the novel PKC family widely expressed in tissue and cell types that has multiple functions, including the regulation of cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.17 In disease models, PKCδ has been linked to ischemic injury of the heart and brain.18–20 However, although PKCδ inhibition protected ex vivo myocardial infarction,19,20 neuronal PKCδ deletion did not protect against transient cerebral ischemic damage,18 suggesting a tissue- or cell type–specific function of PKCδ. In kidneys, we previously reported a role of PKCδ in renal tubular cell injury during cisplatin nephrotoxicity and albumin-induced nephropathy.21–23 However, it is unknown whether PKCδ is involved in ischemic or transplantation-associated kidney injury.

In this study, we have identified PKCδ as a critical regulator of renal tubular injury and regeneration in kidney injury during cold storage–associated transplantation. Blockage of PKCδ either by gene deletion or pharmacologic inhibition in donor kidneys attenuated tissue damage and preserved renal function. Mechanistically, we found that PKCδ may mediate the phosphorylation and activation of the mitochondrial fission protein dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp-1), leading to mitochondrial fragmentation followed by mitochondrial damage and tubular cell death.

Methods

Animals

All animals used in this study were housed in the animal facility of Charlie Norwood Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center. Animal experiments were conducted with the approval of and in accordance with the guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center. Male mice on C57BL/6 background of 10–14 weeks of age were used unless otherwise indicated. PKCδ-knockout (KO) mice were generated by targeted gene deletion as described previously.18

Kidney Transplantation

Kidneys from donor mice were transplanted into syngeneic recipients following previously described procedures with slight modifications.24 Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg intraperitoneally). The left kidney of the donor was excised and flushed with cold heparinized University of Wisconsin (UW) solution and stored in cold UW solution (Belzer UW; Bridge to Life Ltd.) in ice-water bath for the indicated period. For transplantation, the left kidney of the recipient was removed. The donor aortic cuff and renal vein were anastomosed to the recipient abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava, respectively, with 10-0 Ethicon sutures. Graft anastomosis time was standardized at 30 minutes. The ureteral implantation was accomplished by fixing to the exterior wall of the bladder. The end of the ureter was cut and the bladder wall was closed using a 10-0 Ethicon suture. During the recipient surgery, the animals were kept hydrated with normal saline instilled intraperitoneally and were kept on warm heating pads to maintain body temperature. After transplantation, recipient mice were euthanized at the indicated time to collect transplanted kidneys for analysis. To monitor the life-supporting function of transplanted kidneys, the left kidney of the recipient was removed and replaced with the transplant graft, whereas the native right kidney of the recipient was kept for animal survival and graft recovery of initial injury. The native kidney was removed at day 5 post-transplantation to let the mice survive for another day to examine the function and histology of the transplanted kidney at day 6. Renal function was measured as serum creatinine and BUN levels using commercial kits as previously described.25 To determine the effect of the PKCδ inhibitory peptide δV1-1, δV1-1 or TAT-conjugated scramble sequence peptide was injected intraperitoneally at 3 mg/kg to donor mice 30 minutes before graft harvest, included in UW solution at 20 μM during cold preservation, and added to the abdomen immediately after transplantation reperfusion at 3 mg/kg. Purity of the TAT peptides was shown to be ≥98.0% by the manufacturer (GenScript Inc.) in HPLC assay.

Cold-Storage Treatment of Rat Proximal Tubule Cells

Rat proximal tubule cells (RPTCs) were originally from U. Hopfer at Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, OH) and were cultured in Ham F12 Mixture/DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS as described previously.26 For cold storage, complete culture medium was replaced with UW solution to incubate cells at 4°C for indicated times. To simulate rewarming of post-transplantation kidneys, UW solution was replaced with normal culture medium at 37°C for the indicated time. Mitochondrial events including mitochondrial fragmentation, Bax translocation, and cytochrome c release occurred and were examined during cold storage. Cell death was evaluated by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy as previously described.25 Briefly, cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide for 10 minutes. The cells that showed obvious apoptotic morphology (cellular shrinkage, blebbing, and nuclear condensation and fragmentation) were counted as apoptotic cells. Cells with positive propidium iodide staining were counted as necrotic cells. The percentage of cell death including apoptosis and necrosis was estimated in four fields with approximately 200 cells per field.

Transient Transfection of RPTC Cells

Cells were plated at 0.5×106 cells per 35-mm dish to reach 50%–60% confluence after overnight growth. The cells were then transfected with 1 μg PKC plasmids (kinase dead PKCδ [PKCδ-KD], PKCδ active fragment [PKCδ-CF]), or PC-DNA3.1b vector using Lipofectamin 2000 (Invitrogen). To label transfected cells, 0.1 μg pEGFP plasmid was cotransfected. To reveal mitochondrial morphology, 0.5 μg pDsRed2-mito plasmid (Clontech) was transfected alone or 0.1 μg cotransfected with other plasmids. To label PKCδ, pEGFP-PKCδ was transfected. Various PKC plasmids were originally from Jae-Won Soh (Inha University, Inchun, Republic of Korea).

Renal Histology and Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase–Mediated Digoxigenin-Deoxyuridine Nick-End Labeling Assay

For histology, kidney tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for paraffin embedding and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Tubular damage was scored by the percentage of renal tubules with cell lysis, loss of brush border, and cast formation (0, no damage; 1, <25%; 2, 25%–50%; 3, 50%–75%; 4, >75%). For terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining, paraffin-embedded kidney tissue sections were stained with In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science). The slides were examined with fluorescent microscopy, and the TUNEL-positive cells were counted from ten randomly picked images for each specimen in the outer medulla and kidney cortex region. The positve control of TUNEL assay was shown in Supplemental Figure 5.

Isolation of Cytosolic and Mitochondrial Fractions

Cells were fractionated into cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions using mitochondria isolation buffer containing 225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 10 mM Tris–hydrochloride, and protein inhibitor cocktail (pH 7.4) as described in our previous work with minor modifications.27 Briefly, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and suspended in cold mitochondria isolation buffer. The cells were then homogenized by passing through a syringe with a 27-gauge needle five times. The homogenates were centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove cell debris and nuclei followed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes to collect the supernatant as cytosolic fraction and the pellet as mitochondrial fraction. The mitochondrial pellet was washed once with mitochondrial isolation buffer and finally dissolved in 2% SDS buffer for protein analysis. For kidney tissues, mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were collected as described in our recent work with minor modifications.28 Briefly, fresh kidney tissues were homogenized in the mitochondria isolation buffer with 0.1% BSA. The homogenates were centrifuged twice at 1000 × g for 10 minutes to remove cell debris and nuclei, and then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 minutes to collect the supernatant as cytosolic fraction and the pellet as mitochondrial fraction. The mitochondrial pellet was washed and finally dissolved in SDS buffer.

Analysis of Mitochondrial Fragmentation

RPTCs transfected with pDsRed2-mito plasmid were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes followed by a PBS rinse. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342. Mitochondrial morphology was examined with confocal microscopy or regular fluorescent microscopy. To quantify mitochondrial fragmentation, 150–200 cells from ten randomly selected areas were examined for each slide to calculate the percentage of cells with mitochondrial fragmentation as described in our previous studies.12,25,29

Examination of Mitochondrial Fragmentation in Kidney Tissues

At 30 minutes after transplantation, the transplanted kidney was perfused with 1 ml of 10 U/ml heparin, followed by 2 ml fixative containing 100 mM sodium cacodylate, 2 mM calcium chloride, 4 mM magnesium sulfate, 4% paraformaldehyde, and 2.5% glutaraldehyde through the abdominal aorta. The right kidney of donor mice was perfusion fixed similarly during kidney harvest as control. A tissue block of approximately 1 mm3 was collected from each kidney, including a portion of renal cortex and outer medulla for standard processing for electron microscopy. The tissue block was examined initially at low magnification (×3000) to identify representative proximal tubules. Cells in these tubules were then examined at high magnification (×15,000) to collect electron micrographs.

Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblotting was performed using a standard method as previously described.25 The primary antibodies used for immunoblotting were as follows: anti-PKCδ (catalog number ab182126), anti–proliferating cell nuclear antigen (anti-PCNA; ab18197), and anti-CoxIV (ab16056) from Abcam; anti–phospho-Drp1 ser-616 (3455), anti-phospho PKCδ tyrosine 311 (Tyr-311) (2055), HSP60 (4870s), anti–cleaved/active caspase-3 (9664S), anti–cyclophilin B (43603S), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (5174s) from Cell Signalling Technology; Drp1 (611113) and anti–cytochrome c (556433) from BD Pharmingen; anti–mitochondria fission factor (anti-Mff; 17090-1-AP) from Protein Tech; anti-Bax (NT) (06-499) from Upstate Biotechnology; and anti–β-actin (A5441) from Sigma-Aldrich.

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemical Staining

Paraffin-embedded kidney sections were rehydrated and steamed with sodium citrate buffer for antigen retrieval, as recently described.25 RPTCs grown on collagen-coated coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Primary antibodies for immunofluorescence included PKCδ (182126; Abcam), Ki67 (9129; Cell Signaling Technology), γHAX2 (ab26350; R&D System), cytochrome c (556432; BD Pharmingen), and polyclonal anti-Bax (NT) (06-499; Upstate Biotechnology). Cy3-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG, Cy3-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG, and FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG were used as secondary antibodies. Some tissue sections were further stained with Fluorescein labeled Lotus Tetragonolobus Lectin (FL-1321; Vector Labs) to mark proximal tubules.30 Primary antibodies for immunohistochemical staining included Ki67 (9129; Cell Signaling Technology) and Kim-1 (AF1750; R&D System).

Statistical Analyses

The t test was used to show the significant difference between two groups, and ANOVA was used for multigroup comparison. The Dunn multiple comparisons and the Fisher least significant difference test were used for one-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA, respectively. P values <0.05 were considered significant. Data were expressed as mean±SD. GraphPad Prism 8 was used for all calculations.

Results

Cold-Storage Time Determines Tubular Cell Injury and Proliferation in Transplanted Kidneys

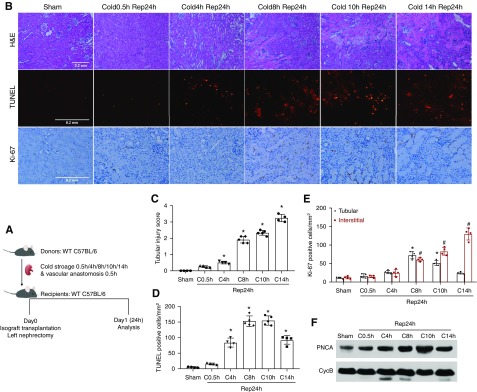

We first observed post-transplantation kidney injury in a mouse model and established the relationship between the duration of cold storage and injury severity. After the harvest operation, donor kidneys were subjected to different durations of cold storage, followed by transplantation (Figure 1A). After cold storage without reperfusion, donor kidneys did not show obvious renal histologic damage in hematoxylin and eosin staining or significant cell death in the TUNEL assay (data not shown). After 24 hours of reperfusion, the transplanted kidneys with 0.5 hours of cold preservation had very mild injury (tissue injury score approximately 0.2) and the injury score did not increase much with 4 hours of cold storage (injury score approximately 0.5). Histologic changes included focal tubular brush border shedding and tubular necrosis in outer medulla (Figure 1B). However, the injury score of post-transplanted kidneys increased remarkably with 8 hours of cold storage (injury score approximately 1.9), and the damage was further aggravated when the donor kidneys had 10 or 14 hours of cold storage (injury scores approximately 2.3 and 3.2, respectively) (Figure 1C). Under these conditions, obvious acute tubular necrosis and microvascular congestion were seen in the outer stripe of the outer medulla (Figure 1B). TUNEL assay detected a significant increase of tubular cell death in transplanted kidneys with 4 hours or longer time cold storage (Figure 1, B and D).

Figure 1.

Cold-storage time determines tubular cell injury and proliferation in transplanted kidneys. (A) Diagram showing the experimental design. The left kidney was collected from C57BL/6 donor mice for 0.5–14 hours of cold storage, followed by transplantation into syngeneic recipient mice for 24 hours of reperfusion. The right kidney of donor mice without cold-storage transplantation was used as sham control. (B) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, TUNEL assay, and Ki67 immunohistochemistry. Scale bars, 0.2 mm. (C) Tubular damage score. (D) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells. (E) Quantification of Ki67-positive tubular or interstitial cells. (F) Immunoblot analysis of PCNA. Cyclophilin B (CycB) was used as the loading control. Data in (B–D) are expressed as mean±SD (n=4–6). *P<0.05 versus sham control. C, cold; Rep, reperfusion.

After acute injury, renal tubules of the kidney display a remarkable intrinsic capacity for regeneration and repair.31 We investigated the effect of cold-storage/ischemia time on tubular proliferation by examining the expression of Ki67, a marker of cell proliferation.32 The representative images of Ki67 staining is shown in Figure 1B with quantification in Figure 1E. As expected, sham control kidneys had very few Ki67-positive cells. Cold storage for 0.5 to 4 hours with reperfusion did not significantly increase tubular Ki67 staining (18–27 cells/mm2), suggesting that mild injury does not induce tubular cell proliferation in this model. Ki67+ tubular cells peaked at 70 cells/mm2 at 8 hours of cold storage with transplantation (Figure 1E). Further extension of cold storage time to 10 or 14 hours reduced the number of Ki67+ cells in renal tubules, indicating that kidney repair is impaired by severe injury. Notably, severe injury was associated with a dramatic increase in interstitial Ki67+ cells (Figure 1E), which is consistent with the infiltration of immune cells into injured kidneys.33 We further detected a marked increase in the expression of PCNA in the cold storage–associated transplantation kidneys, especially in those with 8–14 hours of cold storage (Figure 1F), confirming cell proliferation.

PKCδ Is Activated in Cold-Storage Transplantation Kidneys

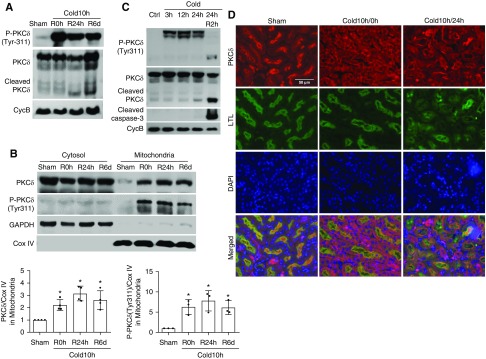

To understand the mechanism of kidney injury and repair during cold storage–associated transplantation, we initially focused on PKCδ, a novel PKC with multiple functions ranging from the regulation of cell growth to differentiation and apoptosis.17 The activation of PKCδ depends on the removal of its autoinhibitory domain from the catalytic domain, which may be induced by the binding of lipid second messenger diacylglycerol, and phosphorylation, translocation, and proteolysis of PKCδ.34,35 It has been reported that phosphorylation at the Tyr-311 site causes a conformational change in PKCδ, resulting in its translocation and activation.36,37 We detected a dramatic increase of PKCδ (Tyr-311) phosphorylation at the end of cold storage of kidneys, and the phosphorylation continued at day 1 and day 6 after kidney transplantation (Figure 2A). In post-transplantation kidneys, we also detected the proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ, which started from day 1 and became evident at day 6 (Figure 2A), further indicating a sustained PKCδ activation during cold storage–associated transplantation. By cellular fractionation, we further showed the accumulation of total and phosphorylated PKCδ in mitochondria in cold storage–associated transplantation kidneys (Figure 2B). In immunofluorescence, PKCδ appeared mostly at the brush border of proximal tubule cells in sham-operated control kidneys (Figure 2D). After cold storage, PKCδ appeared in the cytoplasm and basal membrane of these cells (Figure 2D). In post-transplantation kidneys, there was obvious tubular damage with loss of brush border and, interestingly, PKCδ remained in the cytoplasm and basal membrane of these cells whereas it was enriched in the brush border in relatively healthy proximal tubules (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

PKCδ is activated in cold-storage transplantation kidneys. The left kidney was collected from C57BL/6 donor mice for 10 hours of cold storage, followed by transplantation into syngeneic recipient mice for 0 hours, 24 hours, or 6 days. The right kidney of donor mice without cold storage–associated transplantation was used as sham control. (A) Representative immunoblots to show PKCδ cleavage and the phosphorylation of PKCδ at Tyr-311 in whole kidney lysate. Cyclophilin B (CycB) was used as the loading control. (B) Representative immunoblots and densitometry analysis of PKCδ and phosphorylated PKCδ in renal cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. COX IV and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used as loading controls of mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions, respectively. (C) Representative immunoblots show a rapid and sustained PKCδ (Tyr-311) phosphorylation during cold storage and proteolytic release of the PKCδ catalytic fragment by active caspase-3 during rewarming. Cyclophilin B (CycB) was used as the loading control. (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of PKCδ in renal outer medulla area showing PKCδ translocation. Paraffin-embedded sections were stained for PKCδ with Fluorescein labeled Lotus Tetragonolobus Lectin (LTL) as proximal tubular marker. Data in (B) are expressed as mean±SD (n=3–4). *P<0.05 versus sham control. Ctrl, control; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; R, reperfusion.

Cold-Storage Rewarming Induces Apoptosis, Mitochondrial Damage, and PKCδ Activation in RPTCs

We further analyzed PKCδ activation using an in vitro model of cold storage of tubular cell cultures. To this end, RPTCs were subjected to cold storage in UW solution for different durations, followed by rewarming in full culture medium. Three hours of cold storage with rewarming induced marginal apoptosis in RPTCs, which was increased to 27% and 45% by 12 and 24 hours of cold storage, respectively (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B). This morphologic result was confirmed by immunoblot analysis of PARP cleavage and caspase-3 cleavage or activation (Supplemental Figure 1C). In this model, cold storage induced mitochondrial fragmentation, Bax accumulation in mitochondria, and cytochrome c release from mitochondria into the cytosol (Supplemental Figure 2).

Notably, cold storage led to a rapid PKCδ activation in these cells. As shown in Figure 2C, PKCδ phosphorylation at Tyr-311 was detected during the whole period of cold storage from 3 hours to 24 hours and, after rewarming, there was obvious proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ to release the active fragment, which is associated with caspase activation. By cellular fractionation, we also detected the accumulation of PKCδ and phosphorylated PKCδ to mitochondrial fraction in a manner dependent on cold-storage time (Supplemental Figure 3B). To confirm PKCδ translocation, we transfected the cells with pEGFP-PKCδ to visualize its subcellular localization. In untreated cells, EGFP-PKCδ was diffuse in cytosol; but it showed a perinuclear punctate staining and colocalized with Mito-Red after cold storage (Supplemental Figure 3B), an observation that is in line with PKCδ’s translocation to mitochondria. These cell culture results indicate that PKCδ is activated during cold storage/rewarming and is accompanied by mitochondrial damage and cell death, providing support to our in vivo observation of PKCδ activation in kidney injury by cold storage–associated transplantation (Figure 2).

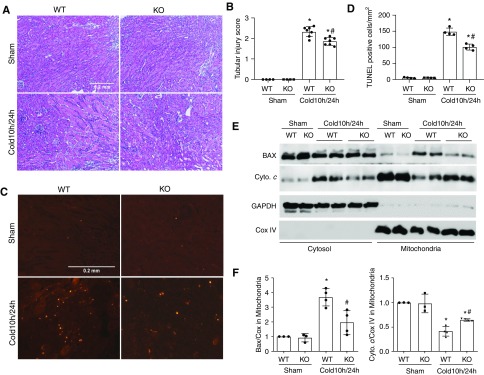

PKCδ Deficiency in Donor Kidney Reduces Cold Storage–Associated Transplantation Injury

To determine the significance of PKCδ activation in kidney injury during cold storage–associated transplantation, we transplanted kidneys from PKCδ-KO mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates into WT recipients. Under control conditions, PKCδ-KO and WT mice displayed normal renal function and histology. Kidneys from these mice were harvested for 10 hours of cold storage followed by transplantation. At 1 day after transplantation, the WT grafts showed numerous lysed/necrotic tubules with notable cast formations in the outer medulla and cortex, whereas PKCδ-KO grafts were better preserved with fewer lysed tubules (Figure 3, A and B). Consistently, less tubular death was detected in PKCδ-KO grafts by TUNEL assay. Quantitatively, the number of TUNEL-positive cells was reduced from 150 in WT to 88 cells per mm2 tissue in PKCδ-KO grafts (Figure 3, C and D). Recruitment of Bax to mitochondria is a characteristic of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis that permeabilizes the mitochondrial outer membrane for release of apoptogenic factors, such as cytochrome c. Bax has also recently been implicated in regulated necrosis or ferroptosis.38 We detected Bax accumulation in mitochondria and the release of cytochrome c in transplanted kidneys, but these changes were less pronounced in PKCδ-KO kidneys than in WT (Figure 3, E and F). These results suggest that PKCδ may contribute to tubular cell death in cold storage–transplanted kidneys by acting on mitochondria.

Figure 3.

PKCδ deficiency in donor kidneys reduces cold storage–associated transplantation injury. The left kidney was collected from PKCδ-KO or WT mice for 10 hours of cold storage, followed by transplantation into WT mice for 24 hours. The right kidney of donor mice without cold-storage transplantation was used as sham control. Kidneys were either fixed for histologic examination or fractionated into cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions for immunoblot analysis. (A) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Scale bar, 0.2 mm. (B) Pathologic score of tubular damage. (C) Representative images of TUNEL staining. Scale bar, 0.2 mm. (D) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells. (E) Representative immunoblots of kidney cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions showing Bax translocation to and cytochrome c release from mitochondria in cold-storage transplantation kidneys. COX IV and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used as the loading controls of mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions, respectively. (F) Quantification of Bax and cytochrome c (Cyto. c) in mitochondria. Data in (B, D, and F) are expressed as mean±SD (n=4–7). *P<0.05 versus the respective sham-operated groups, #P<0.05 versus transplanted WT kidneys.

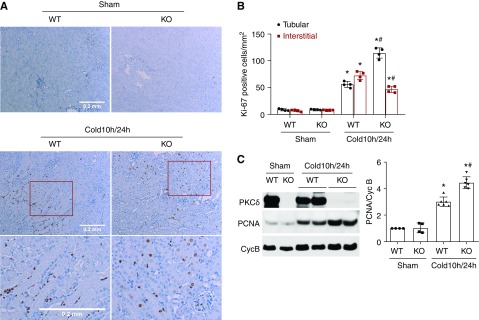

PKCδ Deficiency in Donor Kidneys Increases Tubular Cell Proliferation after Transplantation

We further analyzed tubular cell proliferation in transplanted kidneys. Ki67+ tubular cells were rarely seen in control kidneys regardless of PKCδ (Figure 4A). After 1 day of transplantation after 10 hours of cold storage, WT kidneys showed 50 Ki67+ tubular cells per mm2 tissue, whereas PKCδ-KO grafts had 110 cells per mm2 tissue (Figure 4, A and B). In agreement with Ki67 staining, PKCδ-KO kidneys showed significantly higher PNCA expression than WT after transplantation (Figure 4C). Thus, PKCδ deficiency improved tubular proliferation for kidney repair in transplanted kidneys.

Figure 4.

PKCδ deficiency in donor kidneys increases tubular cell proliferation after transplantation. The left kidney was collected from PKCδ-KO or WT mice for 10 hours of cold storage, followed by transplantation into WT mice for 24 hours. The right kidney of donor mice without cold-storage transplantation was used as sham control. Kidneys were either fixed for histologic examination or lysed for immunoblot analysis. (A) Representative images of Ki67 immunohistochemistry. Bottom panels are enlarged images of the boxed areas in the middle panels. Scale bar, 0.2 mm. (B) Quantification of Ki67-positive tubular cells or interstitial cells. (C) Representative immunoblots and densitometry analysis of PCNA. Cyclophilin B (CycB) was used as loading control and used for normalization in densitometry. Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=4). *P<0.05 versus respective sham control group, #P<0.05 versus cold 10 hours/24 hours WT group.

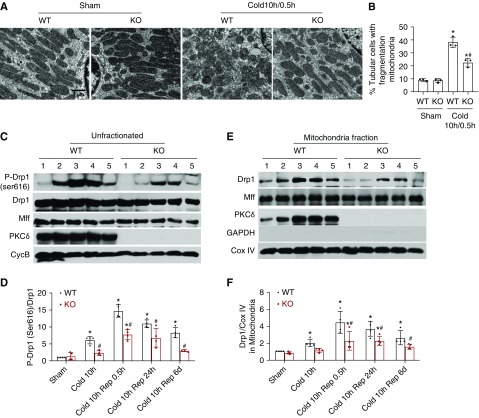

PKCδ Deficiency Suppresses Drp1 Activation and Mitochondrial Fragmentation in Transplanted Kidneys

Mitochondrial fragmentation, as a result of the disruption of mitochondrial dynamics, is an early event in ischemic tissue injury that contributes to mitochondrial damage and cell death.12,13 To further understand PKCδ-mediated mitochondrial damage and tubular cell death in transplanted kidneys, we examined mitochondrial morphology. To this end, donor kidneys were subjected to 10 hours of cold storage, followed by transplantation, and 30 minutes of reperfusion to then fix tissues for electron microscopy. As shown in Figure 5A, proximal tubular cells from sham control kidney displayed filamentous mitochondria that were perpendicular to the base membrane. However, in cold storage–transplanted kidneys, many proximal tubular cells had fragmented mitochondria with a punctate shape and, importantly, mitochondrial fragmentation was significantly reduced in PKCδ-deficient (KO) grafts. In quantification, almost 40% proximal tubular cells in WT renal grafts had fragmented mitochondria after cold storage–associated transplantation, whereas the number was reduced to about 20% in PKCδ-deficient grafts (Figure 5A), suggesting the involvement of PKCδ in mitochondrial fragmentation during cold storage–associated transplantation.Mitochondrial fragmentation in renal IRI involves Drp1, a pivotal mitochondrial fission protein.12 In cold-storage renal transplants, we detected a rapid Drp1 phosphorylation at serine 616 (p-Drp1Ser616; Figure 5, C and D), a well documented mechanism of Drp1 activation.39 Consistently, Drp1 translocation to mitochondria started from cold storage and became most obvious at the early reperfusion stage, and this translocation continued to day 6 after transplantation (Figure 5, E and F). Notably, the Drp1 phosphorylation and translocation were significantly suppressed in PKCδ-deficient transplants (Figure 5, E and F), indicating a role of PKCδ in serine 616 phosphorylation and activation of Drp1. The accumulation of Drp1 in mitochondria often depends on a receptor protein on the mitochondrial outer membrane, for example, Mff,40 but PKCδ WT and KO kidneys had similar MFF expression (Figure 5, C and E). Disruption of mitochondrial fusion may also lead to mitochondrial fragmentation; however, there were no obvious expression changes in mitochondrial fusion proteins including mitofusin 1, mitofusin 2, or optic atrophy 1 (not shown).

Figure 5.

PKCδ deficiency suppresses Drp1 activation and mitochondrial fragmentation in cold storage–transplanted kidneys. The left kidney was collected from PKCδ-KO or WT mice for 10 hours of cold storage, followed by transplantation into WT mice. The right kidney of donor mice without cold-storage transplantation was used as sham control. (A and B) At 30 minutes after transplantation, the kidneys were perfusion fixed for electron microscopy. (A) Representative electron micrographs of mitochondrial morphology in proximal tubule cells. (B) Percentage of proximal tubule cells with mostly fragmented mitochondria (<1% filamentous mitochondria). (C–F) Kidneys were collected from sham, 10 hours of cold storage, 10 hours of cold storage with transplantation/reperfusion for 0.5 hours, 24 hours, or 6 days (labeled as condition 1–5). (C and D) Whole tissues or (E and F) mitochondrial fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting and densitometry for indicated proteins. Quantitative data are expressed as mean±SD (n=3–4). *P<0.05 versus the respective sham control, #P<0.05 versus cold storage–transplanted WT kidneys. Rep, reperfusion.

We further examined the effects of PKCδ on mitochondrial fragmentation and membrane leakage during cold storage of RPTCs. As shown in Supplemental Figure 4, A and B, 24 hours of cold storage induced significant mitochondrial fragmentation in empty pcDNA vector transfected cells, which was partially suppressed by PKCδ-KD but enhanced by PKCδ-CF. Consistently, PKCδ-KD partially inhibited cold storage–associated cytochrome c release from mitochondria, whereas PKCδ-CF increased its release (Supplemental Figure 4, C and D). Also, cellular fractionation analysis revealed the mitochondrial translocation of Drp1, indicating a role of Drp1 in mitochondrial fragmentation in RPTCs (Supplemental Figure 3B). Moreover, cold storage of RPTCs induced Drp1 phosphorylation at serine 616, which was suppressed by PKCδ-KD and enhanced by PKCδ-CF (Supplemental Figure 4C). Together, these results support the in vivo observation in Figure 5 that PKCδ may mediate Drp1 serine 616 phosphorylation to promote mitochondrial fission and fragmentation during renal cold storage–associated transplantation (Supplemental Figure 5).

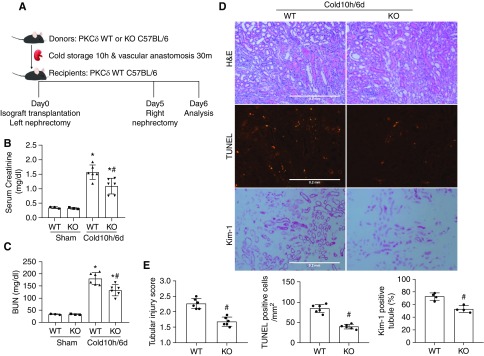

PKCδ-Deficient Grafts Have Better Renal Function and Histology as Life-Supporting Kidneys

Kidney injury after cold-storage transplantation is associated with delayed graft function, which is commonly defined by the need for dialysis in the first week post-transplantation.41,42 To examine graft function in our mouse model, we allowed transplanted kidneys to recover from initial injury for 5 days and then removed the native kidney for 1 day to analyze the function and histology of the transplanted kidney (Figure 6A). After nephrectomy of the native kidney, mice became less active and lost weight (not shown). Serum creatinine and BUN were significantly increased after nephrectomy in these mice, suggesting the transplanted kidney did not have full functional recovery. Compared with the mice receiving WT kidneys, those with PKCδ-KO grafts showed significantly lower serum creatinine and BUN after native kidney nephrectomy (Figure 6, B and C). In histology, kidney injury including tubular necrosis and cast formation resolved at day 6 in comparison with day 1, suggesting kidney repair. However, there were tubular cell flattening, brush border loss, and interstitial infiltration at day 6 (Figure 6D). TUNEL staining indicated persistent tubular cell death, although tubular lysis or necrosis was largely resolved. Consistently, the transplanted kidneys showed positive Kim-1 staining in many renal tubules (Figure 6D). Notably, all of these signs of kidney injury were less pronounced in PKCδ-KO grafts than in WT, suggesting PKCδ deficiency attenuates kidney injury and improves kidney repair after transplantation (Figure 6, D and E). Thus, PKCδ-KO grafts had a better renal histology associated with better renal function as the life-supporting kidney.

Figure 6.

PKCδ-deficient grafts have better renal function and less injury as life-supporting kidneys. (A) Diagram showing the experimental design. The left kidney was collected from PKCδ-KO or WT mice for 10 hours of cold storage, followed by transplantation into WT recipient mice. At day 5 post-transplantation, the native kidney of the recipient mouse was removed so the transplanted kidney became the life-supporting kidney. At day 6, the transplanted kidney and blood samples were collected for analysis. The right kidney of donor mice without cold-storage transplantation was used as sham control. (B) Serum creatinine measurement. (C) BUN measurement. (D) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, TUNEL assay, and Kim-1 immunohistochemistry. (E) Quantitative analysis of tubular damage, TUNEL-positive cells, and Kim-1–positive tubules. Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=4–6). *P<0.05 versus the respective sham-operated grafts, #P<0.05 versus transplanted WT.

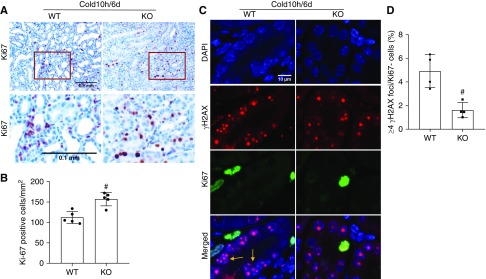

PKCδ Deficiency Improves Tubular Proliferation and Decreases Tubular Senescence in Life-Supporting Grafts

We further analyzed tubular cell proliferation and senescence in PKCδ-KO and WT renal grafts after removal of the native kidney. There were 150 Ki67+ cells per mm2 tissue in PKCδ-KO renal grafts, significantly higher than the 110 Ki67+ cells per mm2 tissue found in WT grafts (Figure 7, A and B). Tubular senescence was indicated by Ki67− cells with high γ-H2AX foci density (four or more foci per nucleus) as previously described (Figure 7, C and D).32,43,44 There were fewer γ-H2AX+/Ki67− cells in PKCδ-KO (approximately 2%) renal grafts than WT (approximately 5%). Thus, PKCδ deficiency enhanced tubular proliferation and suppressed tubular senescence to promote kidney repair after transplantation.

Figure 7.

PKCδ deficiency improves tubular proliferation and decreases tubular senescence in life-supporting grafts. The left kidney was collected from PKCδ-KO or WT mice for 10 hours of cold storage, followed by transplantation into WT recipient mice. At day 5 post-transplantation, the native kidney of the recipient mouse was removed so the transplanted kidney became the life-supporting kidney. At day 6, the transplanted kidney was collected for analysis. (A) Representative images of Ki67 immunohistochemistry. Lower panels are enlarged images of the boxed areas in the upper panels. Scale bar, 0.1 mm. (B) Quantification of Ki67-positive tubular cells. (C) Representative double immunostainings of γH2AX (red) and Ki67 (green). Tubular cells with more than four γ-H2AX foci in nuclei and negative for Ki67 staining were considered senescent (arrows). (D) Quantification of cells with four or more γH2AX foci/Ki67− in kidney tubules. Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=4–5). #P<0.05 versus transplanted WT grafts. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

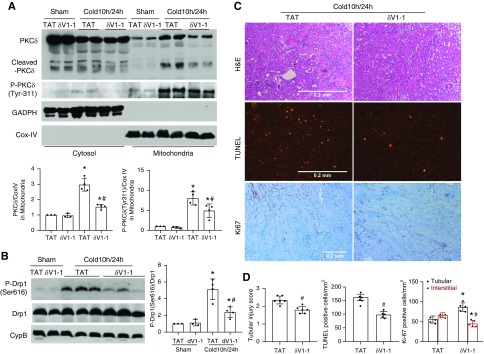

δV1-1 Protects Donor Kidneys in Cold-Storage Renal Transplantation

To explore PKCδ as a therapeutic target in kidney transplantation, we examined the effect of δV1-1, a sequence-based, cell-permeable peptide inhibitor of PKCδ that had been used in vivo to block activation of PKCδ under pathologic conditions in the heart and brain.19,45 δV1-1 or its control TAT peptide was given during the whole process of cold storage–associated transplantation. To verify the inhibitory effect of δV1-1 on PKCδ, we analyzed PKCδ translocation to mitochondria and its proteolytic cleavage in transplanted kidneys (Figure 8A). At 24 hours after transplantation, there was a significant accumulation of total and phosphorylated PKCδ in mitochondria that was attenuated by δV1-1. Cold storage–associated transplantation led to the accumulation of the active PKCδ cleavage fragment in mitochondria, which was also blocked by δV1-1, further confirming the inhibitory effect of δV1-1 on PKCδ in the cold storage–associated transplantation model (Figure 8A). Notably, inhibition of PKCδ by δV1-1 was accompanied by the suppression of Drp1 phosphorylation at serine 616, suggesting an inhibitory effect on mitochondrial fission or fragmentation (Figure 8B). Functionally, δV1-1 had protective effects against kidney tubular damage as shown by renal histology and TUNEL assay of cell death (Figure 8, C and D). Ki67 staining further showed the improvement of cell proliferation by δV1-1 from 52 to 85 cells/mm2 in renal tubules, which was accompanied by a reduction of proliferative cells in renal interstitium (Figure 8, C and D). Together, these results indicate a beneficial effect of pharmacologic PKCδ inhibitors in cold-storage renal transplantation.

Figure 8.

δV1-1 protects donor kidneys in cold storage–associated transplantation. δV1-1 or TAT was injected intraperitoneally to donor mice 30 minutes before graft harvest at 3 mg/kg, included in UW solution during cold preservation at 20 µM, and added to abdomen cavity immediately after graft revascularization at 3 mg/kg. The transplanted kidneys were collected at 24 hours after transplantation for paraffin-embedded section, cytosolic and mitochondrial fractionation, and total kidney tissue lysis. (A) Representative immunoblots and densitometry analysis showing PKCδ and P-PKCδ-Tyr-311 accumulation in mitochondria and its inhibition by δV1-1. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and Cox IV were analyzed as cytosolic and mitochondrial protein loading controls, respectively, which were also used for normalization in densitometry analysis. (B) Representative immunoblots and densitometry analysis of phospho-Drp1 (Ser616) and total Drp1. Total Drp1 was used for normalization in densitometry quantification of p-Drp1. Cyclophilin B (CycB) was used as loading control. (C) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of renal histology, TUNEL assay, and Ki67 immunohistochemistry. Scale bar, 0.2 mm. (D) Pathologic score of tubular damage, quantification of TUNEL-positive cells, and quantification of Ki67-positive cells. Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=4–6). *P<0.05 versus respective sham-operated grafts, #P<0.05 versus TAT-treated transplantation groups.

Discussion

Cold storage is a standard method of organ preservation in transplantation that acts to reduce cellular metabolism to prevent tissue deterioration. However, it is also inherently associated with cold IRI. In human patients, each additional hour of cold-storage ischemia leads to a significant increase in graft failure and mortality after kidney transplantation.42 Renal tubular injury and cell death is critical to kidney injury in cold storage–associated transplantation, but the underlying mechanism is largely unclear. In this study, we have demonstrated: (1) PKCδ is rapidly activated in renal tubular cells during cold-storage transplantation; (2) upon activation, PKCδ translocates to mitochondria where it mediates the phosphorylation and activation of Drp1; (3) Drp1 activation leads to mitochondrial fragmentation, resulting in mitochondrial damage, tubular cell death, and loss of kidney function; (4) genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of PKCδ ameliorates acute injury in cold-storage transplantation and may promote better graft function in the long term. Together, these findings unveil a pathogenic role of PKCδ in cold-storage transplantation that may be a novel therapeutic target.

PKCδ is known to play an important role in the regulation of cell death, survival, and differentiation.17,46 But there are no reports about PKCδ in renal transplantation or IRI. Nonetheless, PKCδ has been implicated in IRI of other organs. For example, Chou et al.18 showed that PKCδ-null mice were resistant to ischemic brain injury or stroke. Notably, by exchanging bone marrow between PKCδ-null and WT mice, their stroke phenotypes were reversed, suggesting that PKCδ regulates brain ischemic injury by working in bone marrow–derived cells and not in neural tissue. In contrast, pharmacologic inhibition of PKCδ by δV1-1 protected the heart from IRI and transgenic overexpression of the PKCδ inhibitory peptide specifically in cardiac myocytes conferred similar cardioprotective effects, supporting a pivotal role of cardiac myocyte PKCδ in IRI in the heart.47,48 These studies suggest that PKCδ may contribute to IRI in a cellular context– and experimental condition–dependent manner by promoting inflammation and/or mediating intrinsic cell death. In this study, we have provided the first evidence for PKCδ regulation of kidney injury in cold-storage transplantation, a model relevant to cold ischemia reperfusion.16,49–51 We show that kidney injury due to cold storage-associated transplantation was markedly reduced when PKCδ was ablated in donor kidneys (Figure 6), indicating an essential role of renal intrinsic PKCδ. In line with this observation, we detected PKCδ activation in kidney tissues, especially in renal tubules (Figure 2). Cold storage also induced PKCδ activation in renal tubular cell cultures (Supplemental Figure 3). In addition to less injury, PKCδ-null kidneys also showed a higher rate of tubular cell proliferation after cold storage–associated transplantation (Figure 4), indicating better kidney repair. Thus, the better function of transplanted PKCδ-null kidneys for life supporting at day 6 after transplantation should be the combined result of less injury and better proliferation or repair in renal tubules.

PKCδ may participate in cell injury and death by multiple mechanisms.17,46 The data in this study indicate that it may induce kidney cell death in cold storage–associated transplantation mainly by inducing mitochondrial damage. We detected an early and sustained accumulation of PKCδ and its active form in mitochondria during kidney transplantation (Figure 2), which was accompanied by Drp1 phosphorylation at serine 616 and translocation to mitochondria, mitochondrial fragmentation (Figure 5), mitochondrial membrane leakage, and tubular cell death (Figure 3). Remarkably, all of these molecular and cellular changes were attenuated in PKCδ-null kidneys (Figures 5 and 6), supporting a role of PKCδ in activating Drp1 for mitochondrial fission or fragmentation under these conditions. These results, however, do not provide the evidence that PKCδ directly phosphorylates Drp1 at serine 616 for its activation. In this regard, Qi et al.52 reported the interaction of PKCδ with Drp1 in brain tissues of hypertensive rats. They further proved the direct phosphorylation of Drp1 by PKCδ at serine 579 in Drp1 isoform 3, which is comparable to the serine 616 in Drp1 isoform 1 in our study.52 PKCδ has been implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction and damage by promoting a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, Bax activation, and production of reactive oxygen species.29,35–38 The results of our study and those of Qi et al.52 indicate that PKCδ may induce these mitochondrial damage phenotypes by activating Drp1 and disrupting mitochondrial dynamics.

Although our data support an important role of PKCδ in Drp1 activation with ensuing mitochondrial fragmentation, damage, and cell death, these changes were significantly—but not completely—attenuated by δV1-1 or PKCδ deficiency in cold storage–associated transplantation. In control conditions, mitochondrial fission and fusion are well balanced to maintain the cellular homeostasis. Under cell stress, mitochondrial fission is increased while fusion may be arrested, resulting in a shift from mitochondrial fusion to fission with consequent mitochondrial fragmentation. Our earlier work demonstrated that Bak (a proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein) normally interacts with both mitofusin 1 and 2 but, upon cell stress, Bak dissociates from mitofusin 2 and enhances its interaction with mitofusin 1, leading to the arrest of mitochondrial fusion.29 Our more recent work further indicated that OPA1, a mitochondrial inner membrane fusion protein, is inactivated by proteolysis during cell stress to prevent the fusion of inner membranes.27 For fission, Drp1 activation and associated mitochondrial fragmentation were shown in experimental models of renal IRI that contributed significantly to kidney injury and functional loss.12 We further suggested the dephosphorylation of Drp1 at serine 637 by calcineurins as a mechanism of Drp1 activation in renal IRI.53 Moreover, Parajuli et al.16 demonstrated the changes in expression of mitochondrial fission-fusion proteins in cold storage–associated transplantation. Therefore, the mechanism of mitochondrial fragmentation in renal warm and cold IRI, including cold storage–associated transplantation, is very complicated and involves regulation and expression changes in both mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins. This complexity provides an explanation for why pharmacologic and genetic inhibition of PKCδ had only partial effects on mitochondrial fragmentation and cell death during kidney cold storage–associated transplantation in this study. Nonetheless, the finding of PKCδ-mediated phosphorylation and activation of Drp1 sheds new light on the mechanism of the disruption of mitochondrial dynamics in kidney diseases.

Another interesting observation in this study is that PKCδ appeared to regulate tubular cell proliferation and kidney repair in cold storage–associated transplantation (Figure 7). Unlike the heart or brain, kidneys have an enormous capacity to repair or recover after IRI, which involves intrinsic tubular cell proliferation for replacement of the lost tubular epithelium.5,54 Cell proliferation is an energy-requiring activity that depends on the activation of the cell cycle. Moderate injury associated with <8 hours of cold-storage ischemia led to tubular cell death while stimulating significant proliferation in surviving tubules after transplantation, but tubular cell proliferation was reduced by severe injury of >10 hours of cold storage (Figure 1). PKCδ deficiency not only suppressed tubular cell death in cold storage–associated transplantation but also improved tubular cell proliferation and reduced senescence (Figure 7). The pleiotropic effect probably stems from the protective effect of PKCδ deficiency against tubular cell injury and death, especially mitochondrial damage in these cells. In support of this possibility, Perry et al.13 reported that deletion of Drp1 from proximal tubules prevented mitochondrial fragmentation and preserved mitochondrial function, resulting in improvement in tubular cell proliferation and kidney recovery after renal IRI. Of note, PKCδ may also directly inhibit the cell cycle by affecting cyclin-dependent kinases.55 Regardless of the mechanism, it is important to verify that enhanced tubular proliferation at the early stage of transplantation improves kidney repair and graft function, because there is a concern that proliferative tubular cells may be more sensitive to apoptosis than quiescent cells, especially in an inflammatory microenvironment.56–58 To clarify this, we allowed the graft to recover from initial injury and removed the native kidney at day 5 after transplantation to observe the function of the transplanted kidney for another day (Figure 6). Under these conditions, the PKCδ-deficient graft showed improved kidney repair with better histology and function compared with the WT graft, indicating that blockade or loss of PKCδ may indeed benefit the transplanted kidney in the long term for life support. Furthermore, a recent study involving renal transplant biopsies demonstrated that degree of expression of the proliferation marker Ki67 correlated with stable or improved renal function.59

The beneficial effects of PKCδ deficiency in cold storage–associated transplantation support the therapeutic potential of pharmacologic inhibitors of PKCδ. The events of transplant injury can be anticipated, which allows the usage of pharmacologic agents before graft harvest or as additives in the storage solution for the improvement of cold IRI intolerance. The PKCδ peptide inhibitor δV1-1 tested in our study rapidly distributes to tissues after intravenous infusion and accumulates more in kidneys than other organs.60 δV1-1 is also well tolerated in animal models and did not have significant adverse events in a phase I/II clinical trial.61 In our current study, δV1-1, when used locally and temporarily during cold storage–associated transplantation, could efficiently suppress the activation, mitochondrial translocation, and proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ in transplanted kidneys, which was accompanied by the suppression of Drp1 serine 616 phosphorylation. Remarkably, δV1-1 reduced kidney injury and improved tubular proliferation (Figure 8), supporting its therapeutic potential for kidney injury during cold storage–associated transplantation.

In summary, we have demonstrated the activation of PKCδ in kidney cold storage–associated transplantation. Upon activation, PKCδ promotes renal tubular cell injury and death, and suppresses tubular cell proliferation and kidney repair. Mechanistically, it may do so by activating Drp1 via phosphorylation, resulting in mitochondrial fragmentation and damage. Inhibition of PKCδ alleviates kidney injury and benefits kidney repair in transplanted kidneys, suggesting the therapeutic potential of targeting PKCδ.

Disclosures

Dr. Dong reports grants from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)/National Institutes of Health (NIH) and grants from VA during the conduct of the study. The authors have nothing else to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported in part by NIDDK/NIH grants DK058831 and DK087843, and US Department of VA Merit Review Award I01 BX000319. Dr. Dong is a recipient of the US Department of VA Senior Research Career Scientist Award.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Daria Mockley-Rosen at Stanford University School of Medicine for providing δV1-1 and Dr. Robert Messing at University of Texas Dell Medical School for originally providing the PKCδ-KO mouse line.

Dr. Dong and Dr. Zhu designed experiments; Dr. Zhu, Dr. Liu, Dr. Shu, Dr. Song, Dr. Xiang, Dr. Yang, and Dr. Zhang performed experiments; Dr. Dong, Dr. Wei, and Dr. Zhu analyzed results; Dr. Dong, Dr. Wei, and Dr. Zhu wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2019101060/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. Cold storage rewarming injury induces apoptosis in cultured tubular cells.

Supplemental Figure 2. Cold storage leads mitochondria fragmentation and leakage.

Supplemental Figure 3. Cold preservation induces PKCδ activation in cultured tubular cells.

Supplemental Figure 4. PKCδ promotes mitochondrial fragmentation and leakage during cold storage.

Supplemental Figure 5. Positive control of TUNEL assay.

References

- 1.Tullius SG, Rabb H: Improving the supply and quality of deceased-donor organs for transplantation. N Engl J Med 378: 1920–1929, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Gustafson SK, Wilk AR, Castro S, et al.: OPTN/SRTR 2017 annual data report: Kidney. Am J Transplant 19[Suppl 2]: 19–123, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schröppel B, Legendre C: Delayed kidney graft function: From mechanism to translation. Kidney Int 86: 251–258, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nehus EJ, Devarajan P: Acute kidney injury: AKI in kidney transplant recipients--here to stay. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 198–199, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonventre JV, Yang L: Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 121: 4210–4221, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linkermann A, Chen G, Dong G, Kunzendorf U, Krautwald S, Dong Z: Regulated cell death in AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2689–2701, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salahudeen AK: Cold ischemic injury of transplanted kidneys: new insights from experimental studies. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F181–F187, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhan M, Brooks C, Liu F, Sun L, Dong Z: Mitochondrial dynamics: Regulatory mechanisms and emerging role in renal pathophysiology. Kidney Int 83: 568–581, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ralto KM, Parikh SM: Mitochondria in acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 36: 8–16, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emma F, Montini G, Parikh SM, Salviati L: Mitochondrial dysfunction in inherited renal disease and acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 267–280, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks C, Cho SG, Wang CY, Yang T, Dong Z: Fragmented mitochondria are sensitized to Bax insertion and activation during apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C447–C455, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks C, Wei Q, Cho SG, Dong Z: Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell culture and rodent models. J Clin Invest 119: 1275–1285, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry HM, Huang L, Wilson RJ, Bajwa A, Sesaki H, Yan Z, et al.: Dynamin-related protein 1 deficiency promotes recovery from AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 194–206, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W, Wang Y, Long J, Wang J, Haudek SB, Overbeek P, et al.: Mitochondrial fission triggered by hyperglycemia is mediated by ROCK1 activation in podocytes and endothelial cells. Cell Metab 15: 186–200, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayanga BA, Badal SS, Wang Y, Galvan DL, Chang BH, Schumacker PT, et al.: Dynamin-related protein 1 deficiency improves mitochondrial fitness and protects against progression of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2733–2747, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parajuli N, Shrum S, Tobacyk J, Harb A, Arthur JM, MacMillan-Crow LA: Renal cold storage followed by transplantation impairs expression of key mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins. PLoS One 12: e0185542, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qvit N, Mochly-Rosen D: The many hats of protein kinase Cδ: One enzyme with many functions. Biochem Soc Trans 42: 1529–1533, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chou WH, Choi DS, Zhang H, Mu D, McMahon T, Kharazia VN, et al.: Neutrophil protein kinase Cdelta as a mediator of stroke-reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 114: 49–56, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Hahn H, Wu G, Chen CH, Liron T, Schechtman D, et al.: Opposing cardioprotective actions and parallel hypertrophic effects of delta PKC and epsilon PKC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 11114–11119, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inagaki K, Chen L, Ikeno F, Lee FH, Imahashi K, Bouley DM, et al.: Inhibition of delta-protein kinase C protects against reperfusion injury of the ischemic heart in vivo. Circulation 108: 2304–2307, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang D, Pan J, Xiang X, Liu Y, Dong G, Livingston MJ, et al.: Protein kinase Cδ suppresses autophagy to induce kidney cell apoptosis in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1131–1144, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Pabla N, Wei Q, Dong G, Messing RO, Wang CY, et al.: PKC-delta promotes renal tubular cell apoptosis associated with proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1115–1124, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pabla N, Dong G, Jiang M, Huang S, Kumar MV, Messing RO, et al.: Inhibition of PKCδ reduces cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity without blocking chemotherapeutic efficacy in mouse models of cancer. J Clin Invest 121: 2709–2722, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang JJ, Hockenheimer S, Bickerstaff AA, Hadley GA: Murine renal transplantation procedure. J Vis Exp (29): 1150, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei Q, Sun H, Song S, Liu Y, Liu P, Livingston MJ, et al.: MicroRNA-668 represses MTP18 to preserve mitochondrial dynamics in ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 128: 5448–5464, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woost PG, Orosz DE, Jin W, Frisa PS, Jacobberger JW, Douglas JG, et al.: Immortalization and characterization of proximal tubule cells derived from kidneys of spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Kidney Int 50: 125–134, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho SG, Xiao X, Wang S, Gao H, Rafikov R, Black S, et al.: Bif-1 interacts with prohibitin-2 to regulate mitochondrial inner membrane during cell stress and apoptosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1174–1191, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng J, Li X, Zhang D, Chen JK, Su Y, Smith SB, et al.: Hyperglycemia, p53, and mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis are involved in the susceptibility of diabetic models to ischemic acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 87: 137–150, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brooks C, Wei Q, Feng L, Dong G, Tao Y, Mei L, et al.: Bak regulates mitochondrial morphology and pathology during apoptosis by interacting with mitofusins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 11649–11654, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barresi G, Tuccari G, Arena F: Peanut and Lotus tetragonolobus binding sites in human kidney from congenital nephrotic syndrome of Finnish type. Histochemistry 89: 117–120, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agarwal A, Dong Z, Harris R, Murray P, Parikh SM, Rosner MH, et al.; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative XIII Working Group: Cellular and molecular mechanisms of AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1288–1299, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Besschetnova TY, Brooks CR, Shah JV, Bonventre JV: Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat Med 16: 535–543, 1p following 143, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang HR, Rabb H: Immune cells in experimental acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 88–101, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinberg SF: Structural basis of protein kinase C isoform function. Physiol Rev 88: 1341–1378, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinberg SF: Distinctive activation mechanisms and functions for protein kinase Cdelta. Biochem J 384: 449–459, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rybin VO, Guo J, Sabri A, Elouardighi H, Schaefer E, Steinberg SF: Stimulus-specific differences in protein kinase C delta localization and activation mechanisms in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 279: 19350–19361, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Q, Langston JC, Tang Y, Kiani MF, Kilpatrick LE: The role of tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase C delta in infection and inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 20: E1498, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linkermann A: Nonapoptotic cell death in acute kidney injury and transplantation. Kidney Int 89: 46–57, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koval OM, Nguyen EK, Santhana V, Fidler TP, Sebag SC, Rasmussen TP, et al.: Loss of MCU prevents mitochondrial fusion in G1-S phase and blocks cell cycle progression and proliferation. Sci Signal 12: eaav1439, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otera H, Wang C, Cleland MM, Setoguchi K, Yokota S, Youle RJ, et al.: Mff is an essential factor for mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1 during mitochondrial fission in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 191: 1141–1158, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kayler LK, Srinivas TR, Schold JD: Influence of CIT-induced DGF on kidney transplant outcomes. Am J Transplant 11: 2657–2664, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Debout A, Foucher Y, Trébern-Launay K, Legendre C, Kreis H, Mourad G, et al.: Each additional hour of cold ischemia time significantly increases the risk of graft failure and mortality following renal transplantation. Kidney Int 87: 343–349, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawless C, Wang C, Jurk D, Merz A, Zglinicki T, Passos JF: Quantitative assessment of markers for cell senescence. Exp Gerontol 45: 772–778, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braun H, Schmidt BM, Raiss M, Baisantry A, Mircea-Constantin D, Wang S, et al.: Cellular senescence limits regenerative capacity and allograft survival. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1467–1473, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi X, Inagaki K, Sobel RA, Mochly-Rosen D: Sustained pharmacological inhibition of deltaPKC protects against hypertensive encephalopathy through prevention of blood-brain barrier breakdown in rats. J Clin Invest 118: 173–182, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reyland ME, Jones DN: Multifunctional roles of PKCδ: Opportunities for targeted therapy in human disease. Pharmacol Ther 165: 1–13, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inagaki K, Hahn HS, Dorn GW 2nd, Mochly-Rosen D: Additive protection of the ischemic heart ex vivo by combined treatment with delta-protein kinase C inhibitor and epsilon-protein kinase C activator. Circulation 108: 869–875, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn HS, Yussman MG, Toyokawa T, Marreez Y, Barrett TJ, Hilty KC, et al.: Ischemic protection and myofibrillar cardiomyopathy: dose-dependent effects of in vivo deltaPKC inhibition. Circ Res 91: 741–748, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei J, Wang Y, Zhang J, Wang L, Fu L, Cha BJ, et al.: A mouse model of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury solely induced by cold ischemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 317: F616–F622, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lo S, MacMillan-Crow LA, Parajuli N: Renal cold storage followed by transplantation impairs proteasome function and mitochondrial protein homeostasis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 316: F42–F53, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aufhauser DD Jr, Wang Z, Murken DR, Bhatti TR, Wang Y, Ge G, et al.: Improved renal ischemia tolerance in females influences kidney transplantation outcomes. J Clin Invest 126: 1968–1977, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qi X, Disatnik MH, Shen N, Sobel RA, Mochly-Rosen D: Aberrant mitochondrial fission in neurons induced by protein kinase Cdelta under oxidative stress conditions in vivo. Mol Biol Cell 22: 256–265, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cho SG, Du Q, Huang S, Dong Z: Drp1 dephosphorylation in ATP depletion-induced mitochondrial injury and tubular cell apoptosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F199–F206, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Humphreys BD, Cantaluppi V, Portilla D, Singbartl K, Yang L, Rosner MH, et al.; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) XIII Work Group: Targeting endogenous repair pathways after AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 990–998, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Griner EM, Kazanietz MG: Protein kinase C and other diacylglycerol effectors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 7: 281–294, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DiRocco DP, Bisi J, Roberts P, Strum J, Wong KK, Sharpless N, et al.: CDK4/6 inhibition induces epithelial cell cycle arrest and ameliorates acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F379–F388, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomasova D, Anders HJ: Cell cycle control in the kidney. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 1622–1630, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Megyesi J, Andrade L, Vieira JM Jr, Safirstein RL, Price PM: Positive effect of the induction of p21WAF1/CIP1 on the course of ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int 60: 2164–2172, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cassis P, Solini S, Azzollini N, Aiello S, Rocchetta F, Conti S, et al.: An unanticipated role for survivin in organ transplant damage. Am J Transplant 14: 1046–1060, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyaji Y, Walter S, Chen L, Kurihara A, Ishizuka T, Saito M, et al.: Distribution of KAI-9803, a novel δ-protein kinase C inhibitor, after intravenous administration to rats. Drug Metab Dispos 39: 1946–1953, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lincoff AM, Roe M, Aylward P, Galla J, Rynkiewicz A, Guetta V, et al.; PROTECTION AMI Investigators: Inhibition of delta-protein kinase C by delcasertib as an adjunct to primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Results of the PROTECTION AMI Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur Heart J 35: 2516–2523, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.