Abstract

Acetaminophen (APAP) overdose causes hepatotoxicity involving mitochondrial dysfunction. Previous studies showed that translocation of Fe2+ from lysosomes into mitochondria by the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) promotes the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) after APAP. Here, our Aim was to assess protection by iron chelation and MCU inhibition against APAP hepatotoxicity in mice. C57BL/6 mice and hepatocytes were administered toxic doses of APAP with and without starch-desferal (an iron chelator), minocycline (MCU inhibitor), or N-acetylcysteine (NAC). In mice, starch-desferal and minocycline pretreatment decreased ALT and liver necrosis after APAP by >60%. At 24 h after APAP, loss of fluorescence of mitochondrial rhodamine 123 occurred in pericentral hepatocytes often accompanied by propidium iodide labeling, indicating mitochondrial depolarization and cell death. Starch-desferal and minocycline pretreatment decreased mitochondrial depolarization and cell death by more than half. In cultured hepatocytes, cell killing at 10 h after APAP decreased from 83% to 49%, 35% and 27%, respectively, by 1 h posttreatment with minocycline, NAC, and minocycline plus NAC. With 4 h posttreatment in vivo, minocycline and minocycline plus NAC decreased ALT and necrosis by ~20% and ~50%, respectively, but NAC alone was not effective. In conclusion, minocycline and starch-desferal decrease mitochondrial dysfunction and severe liver injury after APAP overdose, suggesting that the MPT is likely triggered by iron uptake into mitochondria through MCU. In vivo, minocycline and minocycline plus NAC posttreatment after APAP protect at later time points than NAC alone, indicating that minocycline has a longer window of efficacy than NAC.

Keywords: acetaminophen, calcium uniporter, iron, minocycline, mitochondria, liver

INTRODUCTION

Acetaminophen (APAP) overdose produces fulminant hepatic necrosis and is the leading cause of acute liver failure in North America (Fontana, 2008). APAP hepatotoxicity is dose-dependent and reproducible in animal models. However, after more than 40 years of investigation, the mechanism of APAP-induced liver injury is still not fully understood. Important in APAP toxicity is generation by cytochrome P450 oxidation of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI) from APAP, which is usually detoxified by glutathione (Mitchell et al., 1973a; James et al., 2003a). However, after glutathione exhaustion, covalent binding of NAPQI to protein occurs, which promotes oxidative stress and onset of the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT), resulting in hepatocellular death (Bajt et al., 2004; Kon et al., 2004; Reid et al., 2005; Hanawa et al., 2008).

A number of studies have examined the importance of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in APAP toxicity (Walker et al., 1980; Burcham and Harman, 1991; Donnelly et al., 1994; Hu et al., 2016b; Ramachandran et al., 2018). The MPT, an abrupt increase in the permeability of the mitochondrial inner membrane to solutes up to a molecular mass of about 1500, has emerged as a major mechanism in APAP hepatotoxicity (Kon et al., 2004; Masubuchi et al., 2005). The MPT is promoted by oxidative stress, which in turn promotes more oxidative stress (Nicotera et al., 1989; Chen et al., 2008). Iron, which catalyzes hydroxyl radical (•OH) formation by Fenton reaction, plays a critical role in oxidative stress in injuries to many organs, including liver, heart, kidney and brain (Pucheu et al., 1993; Ghate et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Fenton chemistry may also have an important role in APAP hepatotoxicity (Adamson and Harman, 1993; Winterbourn, 1995). Iron-catalyzed •OH formation is initiated by O2•− formation and dismutation to H2O2. H2O2 further reacts with Fe2+ to yield •OH and Fe3+. Subsequent reaction of Fe3+ with O2•− then regenerates Fe2+ to continue the reaction. Lysosomal-mitochondrial cross-talk also modulates oxidative stress-dependent cell injury, including APAP hepatotoxicity (Kurz et al., 2007; Uchiyama et al., 2008; Kon et al., 2010; Moles et al., 2018).

Previously, we identified lysosomes/endosomes, which rupture after APAP treatment, as the source of cytosolic mobilizable chelatable iron in APAP hepatotoxicity (Uchiyama et al., 2008; Kon et al., 2010). This Fe2+ is then taken up into mitochondria via the electrogenic mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) to promote intramitochondrial •OH formation by the Fenton reaction, which in turn causes MPT onset and mitochondrial depolarization (Hu et al., 2016a).

Previous studies show that the iron chelator, desferal, decreases APAP-induced hepatotoxicity (Schnellmann et al., 1999; Kon et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2016a). Starch-desferal is synthesized by covalently attaching desferal to a modified starch polymer. This high-molecular-weight chelator retains the affinity and specificity of desferal for iron. Starch-desferal has prolonged vascular retention and greatly reduced acute toxicity as compared with an equivalent dose of desferal (Harmatz et al., 2007). Starch-desferal is taken up into cells by endocytosis and localizes into the lysosomal/endosomal compartment. Starch-desferal, also prevents mitochondrial depolarization and protects cultured hepatocytes against cell death after APAP (Kon et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2016a). However, the effect of starch-desferal on APAP-induced hepatotoxicity in vivo is not known.

MCU transports Fe2+ into mitochondria during oxidative injury to hepatocytes (Flatmark and Romslo, 1975; Uchiyama et al., 2008). Minocycline is a semisynthetic tetracycline antibiotic that protects against neurodegenerative disease, trauma and ischemia/reperfusion injury (Zhu et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2003; Kelly et al., 2004; Chu et al., 2005; Theruvath et al., 2008; Czerny et al., 2012; Aras et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2015). Minocycline also blocks mitochondrial Fe2+ uptake via MCU, suggesting that protection may be by preventing mitochondrial Fe2+ uptake (Schwartz et al., 2013). The glutathione precursor N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is used to treat patients with APAP overdose. However, protection becomes ineffective when NAC is given later than 2 h after APAP overdose in animal studies (Saito et al., 2010). Here, we show that minocycline and starch-desferal protect against mitochondrial dysfunction and hepatic injury after APAP in a mouse model. We show further that therapeutic post-treatment with minocycline is more effective than NAC against APAP overdose-induced liver injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Starch-desferal was the generous gift of Biomedical Frontiers (Minneapolis, MN). Minocycline, tetracycline, N-acetylcysteine, rhodamine 123 (Rh123), propidium iodide (PI), and other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (8–9 weeks) were housed in an environmentally controlled room with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. After overnight fasting, mice were treated with vehicle (warm saline) or APAP (300 mg/kg, i.p.), and food was then made available. Starch-desferal (100 mg/kg), minocycline (10 mg/kg), NAC (300 mg/kg) and vehicle (warm saline) were administrated i.p. 1 h before or 4 h after APAP. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation and Culture of Mouse Hepatocytes

Hepatocytes were isolated from 20 to 25 g overnight-fasted male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) by collagenase perfusion through the inferior vena cava, as described previously (Uchiyama et al. 2008). Hepatocytes were resuspended in Waymouth’s medium MB-752/1 supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum, 100 nM insulin, 100 nM dexamethasone, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, as previously described (Qian et al. 1997). Cell viability was greater than 85% by trypan blue exclusion. Hepatocytes were plated on 0.1% type 1 rat tail collagen-coated 24-well microtiter plates (1.5 × 105 cells per well). After attaching for 3 h in humidified 5% CO2, 95% air at 37°C, hepatocytes were washed once and placed in hormonally defined medium (HDM) consisting of RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 240 nM insulin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 μg/ml transferrin, 0.3 nM selenium, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at pH 7.4.

Fluorimetric Assay of Cell Viability

Cell death were assessed using a NovoStar multiwell plate reader (BMG Lab Technologies, Offenburg, Germany), as previously described (Nieminen et al., 1992). Briefly, after attachment to 24-well plates for 3 h, hepatocytes were washed once and HDM containing 30 μM PI (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) was added. Hepatocytes were then incubated with 10 mM APAP. In some experiments, hepatocytes were treated with 4 μM minocycline and/or 20 mM NAC at 1 h before APAP or at 2 or 4 h after APAP. PI fluorescence from each well was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 544 nm and 620 (40-nm bandpass), respectively. For each well, fluorescence was first measured at 20 min after addition of PI (Initial) and then at various times after treatment of APAP (X). Experiments were terminated by permeabilizing plasma membranes with 375 μM digitonin. After another 20 min, a final fluorescence measurement (Final) was collected. The percentage of nonviable cells (D) was calculated as D = 100(X -Initial)/(Final - Initial). Cell killing assessed by PI fluorimetry correlates closely with trypan blue exclusion and enzyme release as indicators of oncotic necrosis (Nieminen et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2003).

Alanine aminotransferase

At 24 hours after vehicle or APAP injection, mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (100 and 10 mg/kg, respectively, i.p.), and blood was collected from the inferior vena cava. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was measured using a commercial kit (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI).

Histology

Histology was evaluated at 24 h after vehicle or APAP injection. Liver tissues were fixed by immersion in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. In sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), 10 random fields per slide were assessed for necrosis by standard morphologic criteria (e.g., loss of architecture, vacuolization, karyolysis). Images were captured in a blinded manner using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) and a 10X objective lens. Necrotic areas were quantified by computerized image analysis using IP Lab version 3.7 software (BD Biosciences, Rockville, MD) by dividing necrotic areas by total area of the images.

Glutathione Measurement

At 0 to 24 h after APAP or vehicle, mice were euthanized and small pieces of liver tissue were quickly dissected and homogenized in lysis buffer at 4. Total glutathione (GSH plus GSSH) in liver homogenates was measured with a commercial kit (OXIS International, Portland, OR) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Intravital Multiphoton Microscopy

At 24 h after vehicle or APAP injection, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and connected to a small animal ventilator via a respiratory tube (20-gauge catheter) inserted into the trachea. Green-fluorescing Rh123 (2 μmol/mouse) and red-fluorescing PI (0.4 μmol/mouse), indicators of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ) and cell death, respectively, were infused via polyethylene-10 tubing inserted into the femoral vein over 10 min (Theruvath et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2016b). After infusion of these fluorescent probes, individual mice were laparotomized and placed in a prone position. The liver was gently withdrawn from the abdominal cavity and placed over a #1.5 glass coverslip mounted on the stage of an inverted Olympus Fluoview 1200 MPE multiphoton microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) equipped with a 60X 1.30 NA silicone oil-immersion objective lens and a Spectra Physics Mai Tai Deep Sea tunable multiphoton laser (Newport, Irvine, CA). Non-descanned green and red fluorescence were separated using 495–540-nm and 575–630-nm band pass filters. Rh123 and PI fluorescence was imaged simultaneously using 800-nm multiphoton excitation. Unless otherwise stated, images were collected 25 μm from the liver surface. Pericentral areas were identified from the sinusoidal configuration under the microscope.

Punctate green Rh123 and red TMRM fluorescence in hepatocytes represented polarized mitochondria, whereas dimmer diffuse fluorescence signified mitochondrial depolarization. Depolarized areas were quantified in 10 random fields using IP Lab version 3.7 software (BD Biosciences, Rockville, MD) by dividing depolarized areas by total area of the images. Nonviable PI-positive cells, indicated by red nuclear fluorescence, were also counted in ten random fields per liver.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Images shown are representative of three or more experiments. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test using p < 0.05 as the criterion.

RESULTS

Starch-desferal and minocycline decrease acetaminophen-induced ALT release and necrosis

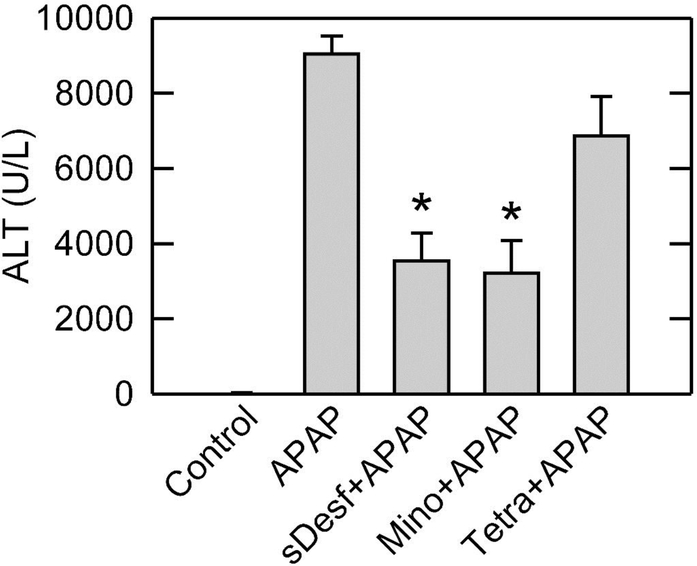

Liver injury after APAP overdose was assessed from ALT release and cell necrosis. Control mice had serum ALT of 32 ± 7.3 U/L. When mice were treated with 300 mg/kg APAP, ALT increased to 9,041 ± 480 U/L after 24 h (Fig. 1), as observed by others (McGill et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2015). After pretreatment with 100 mg/kg starch-desferal or 10 mg/kg minocycline 1 h before APAP addition, ALT decreased to 3538 ± 737 U/L and 3214 ± 862 U/L at 24 h, respectively (P<0.01). Identical treatment with tetracycline did not cause a statistically significant change of serum ALT (6860 ± 1060 U/L) compared to vehicle. To avoid the unnecessary use of animals, we did not evaluate mice treated with starch-desferal, minocycline or tetracycline alone. These agents have been well studied clinically and in animal models to show an absence of acute toxicity at the doses used, especially in the liver (Andrade and Tulkens, 2011; Czerny et al., 2012; Kholmukhamedov et al., 2014; Urban et al., 2017; Nasrallah et al., 2019).

Fig. 1. Starch-desferal and minocycline decrease ALT release after APAP overdose.

Mice were administered 300 mg/kg APAP or vehicle. Starch-desferal (100 mg/kg), minocycline (10 mg/kg), tetracycline (10 mg/kg), or vehicle was given 1 h before APAP, as described in Materials and Methods. Serum ALT was assessed 24 h after APAP. Values are means ± SE from four or more mice per group. *, p<0.01 vs vehicle and tetracycline.

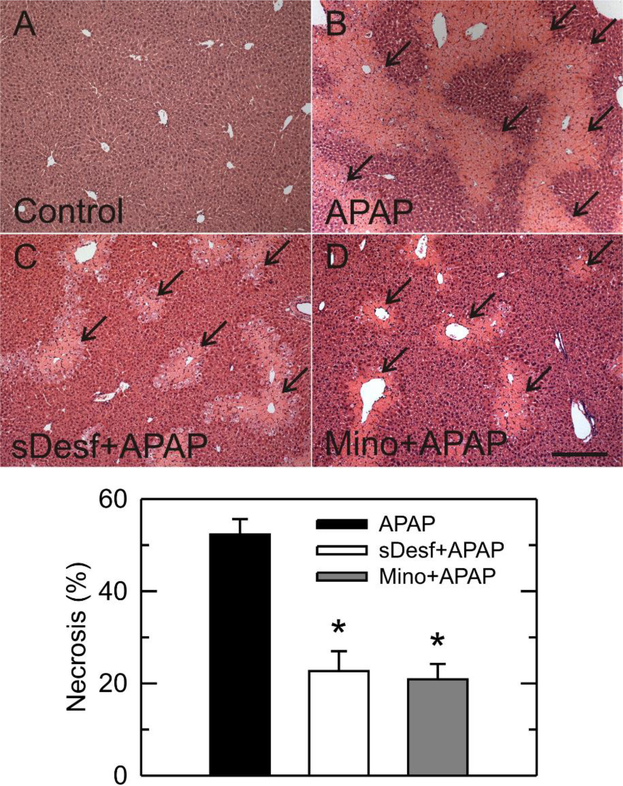

Histology of control livers was normal. By contrast at 24 h after 300 mg/kg APAP, necrotic areas increased to 52% with a predominately pericentral distribution. This necrosis decreased to 22% and 20% by starch-desferal and minocycline, respectively (Fig. 2) (p<0.05). Overall, starch-desferal and minocycline markedly reduced liver injury after APAP.

Fig. 2. Starch-desferal and minocycline decrease necrosis after APAP.

Mice were treated with vehicle (A), APAP (B), APAP plus starch-desferal (C), and APAP plus minocycline (D), as described in Fig. 1. Black arrows identify necrotic areas. Area percent of necrosis was quantified in liver sections by image analysis of 10 random fields per liver. Necrosis in vehicle group was absent and not plotted. Bar is 200 μm. *, p< 0.05.

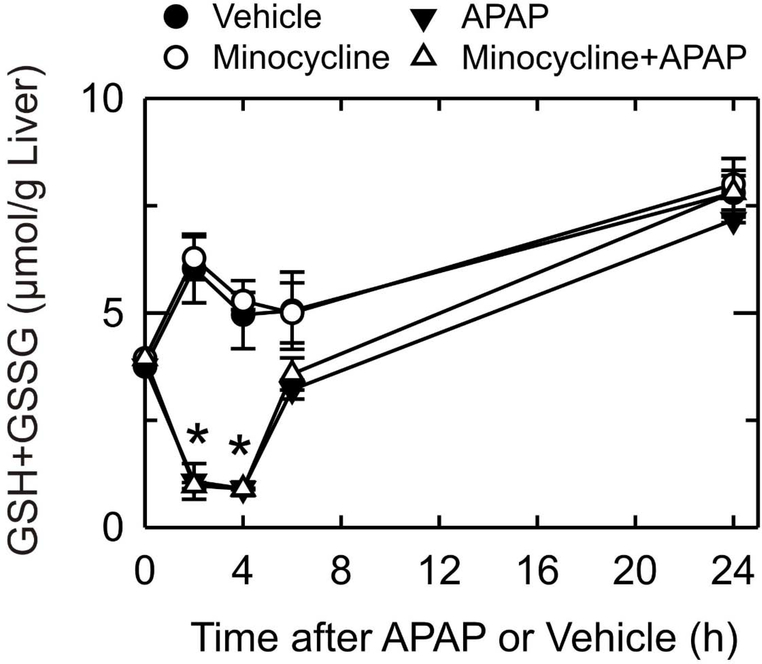

Minocycline does not alter glutathione depletion after acetaminophen

To investigate whether minocycline affected the metabolism of APAP, total glutathione in liver tissue was measured (Fig. 3). Glutathione in livers of control mice not exposed to APAP increased 62%, 32%, 43% and 110% after 2, 4, 6 and 24 h, respectively. Increasing glutathione was due to refeeding of mice after fasting at the beginning of the experiment, since fasting causes a decrease of hepatic glutathione (Vogt and Richie, 1993). Minocycline had no effect on this glutathione recovery. After APAP, total glutathione decreased by 71% and 76% after 2 and 4 h, respectively, and then began to recover after 6 h. After 24 h, glutathione had recovered completely and was not different from APAP-untreated livers. Minocycline pretreatment did not change glutathione depletion and subsequent recovery after APAP treatment. Adduct formation between glutathione and NAPQI causes glutathione depletion after APAP, and the rate of glutathione depletion parallels that for NAPQI formation (Mitchell et al., 1973a; Mitchell et al., 1973b; Jaeschke, 1990). Thus, minocycline did not alter APAP metabolism.

Fig. 3. Minocycline does not alter APAP-induced glutathione depletion.

Mice were treated with vehicle, minocycline and/or APAP, as described in Fig. 1. After 0 to 24 h of treatment with APAP, liver homogenates were prepared, and total glutathione in liver was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means ± SE from 3 mice per group. *, p<0.01 vs vehicle.

Starch-desferal and minocycline prevent mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in vivo after acetaminophen

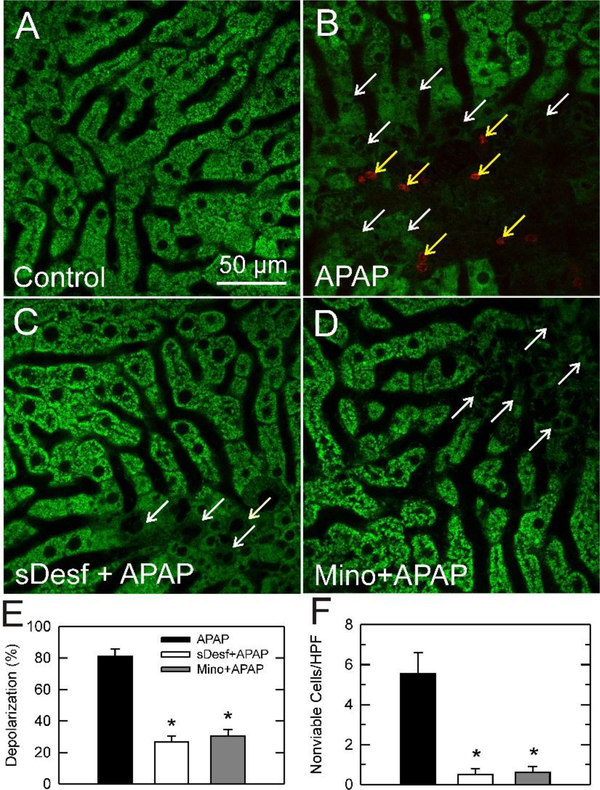

Mitochondria dysfunction is closely related to liver injury. Therefore, we explored whether mitochondrial depolarization occurred after APAP overdose using intravital multiphoton microscopy. In control mice, green fluorescence of Rh123 was punctate in virtually all hepatocytes, indicating mitochondria polarization (Fig. 4A). Cytosolic and nuclear areas had little fluorescence. Red PI labeling of nuclei, an indicator of cell death, was rare. By contrast at 24 h after APAP overdose, Rh123 staining became diffuse and dim in many hepatocytes in a predominately pericentral distribution, indicating mitochondrial depolarization (Fig. 4B, white arrows). Additionally, some nuclei of hepatocytes with depolarized mitochondria labeled with the red-fluorescing PI (Fig. 4B, yellow arrows). Overall, all nonviable cells had depolarized mitochondria. However, many hepatocytes with diffuse and dim Rh123 staining were not yet labeled with PI, indicating that mitochondrial depolarization occurred before cell death.

Fig. 4. Starch-desferal and minocycline decrease mitochondrial depolarization and hepatocellular cell death after APAP.

Mice were treated with vehicle, starch-desferal or minocycline followed by 300 mg/kg APAP or vehicle, as described in Fig. 1. At 24 h after APAP, livers were visualized by multiphoton microscopy, as described in Materials and Methods. Shown are representative overlay images of green Rh123 and red PI fluorescence collected from livers of mice treated with: (A) vehicle only, (B) APAP only, (C) 100 mg/kg starch-desferal 1 h before APAP, (D) 10 mg/kg minocycline 1 h before APAP. Punctate labeling of Rh123 signifies mitochondrial polarization, whereas diffuse, dim cellular staining denotes mitochondrial depolarization (white arrows). Nuclear PI labeling signifies cell death (yellow arrows). In E, the average percentage of hepatocytes with depolarized mitochondria is plotted for various treatment groups from 10 random fields for 3–4 livers per group. In F, PI-labeled nuclei were also counted in 10 random fields for each liver. Depolarization and cell death were absent in vehicle-treated livers and not plotted. *, p<0.05 vs. APAP alone.

After APAP following starch-desferal treatment, fewer hepatocytes had depolarized mitochondria, and most hepatocytes showed bright punctate staining of Rh123, indicating mitochondrial polarization (Fig. 4C, white arrows, compare to 4B). PI labeling of nuclei also decreased after starch-desferal treatment. Similarly, minocycline treatment decreased mitochondrial depolarization and loss of cell viability after APAP (Fig. 4D, white arrows). By contrast, mitochondrial depolarization and cell death after tetracycline treatment were indistinguishable from vehicle-treated mice (data not shown).

At 24 h after APAP, hepatocytes were counted and scored for Rh123 and PI labeling (Fig. 4E, F). In control livers that were not treated with APAP, virtually every hepatocyte contained polarized mitochondria, and PI-labeled nonviable cells were absent. At 24 h after APAP, 81% of hepatocytes contained depolarized mitochondria, and nonviable hepatocytes were 5.5 ± 1.0 cells/HPF (Fig. 4E, F). Starch-desferal treatment decreased mitochondrial depolarization and nonviable cells to 27% and 0.5 ± 0.3 cells/HPF, respectively (P<0.05). After APAP with minocycline treatment, hepatocytes with depolarized mitochondria also decreased to 30% and nonviable cells decreased to 0.6 ± 0.3 cells/HPF (Fig. 4E, F) (P<0.05). Thus, starch-desferal and minocycline conferred similar protection. Because starch-desferal is a lysosomally targeted iron chelator and minocycline is an MCU inhibitor, these results are consistent with the conclusion that APAP overdose induces lysosomal iron release and uptake into mitochondria in vivo to cause hepatotoxicity.

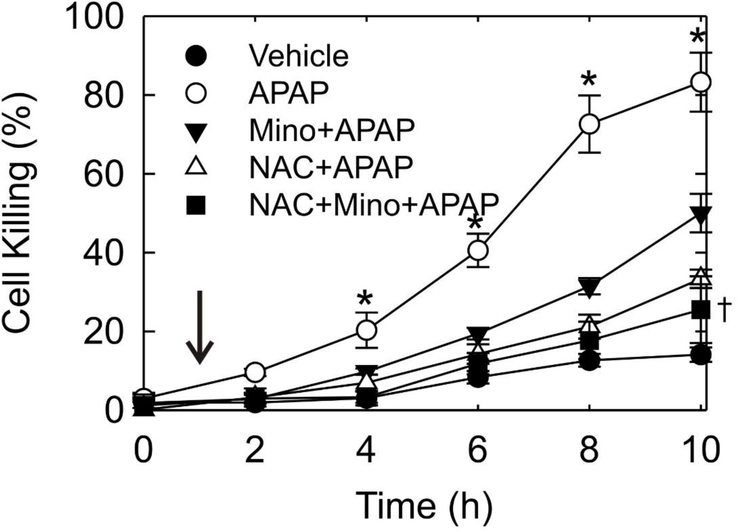

Minocycline and NAC treatment after acetaminophen decreases cell killing in vitro

To test the therapeutic effect of minocycline against APAP hepatotoxicity compared to NAC, mouse hepatocytes were post-treated 1 h after 10 mM APAP with minocycline, NAC, and minocycline plus NAC. Cell killing was determined by PI fluorimetry. After APAP, hepatocytes progressively lost viability, leading to 83% cell death at 10 h. Post-treatment at 1 h with minocycline or NAC individually attenuated cell killing to 49% and 37% at 10 h, respectively (Fig. 5). The combination of minocycline and NAC decreased cell killing to 27%, which was a statistically significant improvement compared to minocycline alone (p<0.05) but not to NAC alone (p=0.14).

Fig. 5. Protection against hepatocyte killing in vitro by treatment with minocycline and/or NAC at 1 h after APAP addition.

Mouse hepatocytes were exposed to 10 mM APAP (0 h) and treated with 4 μM minocycline, 20 mM NAC, 4 μM minocycline plus 20 mM NAC or no addition after 1 h (arrow). Cell viability was determined by PI fluorometry. Vehicle represents hepatocytes unexposed to APAP or other subsequent addition. Values are means ± SE from three or more hepatocyte isolations. *, p<0.01 vs other groups; †, p<0.05 vs Mino+APAP.

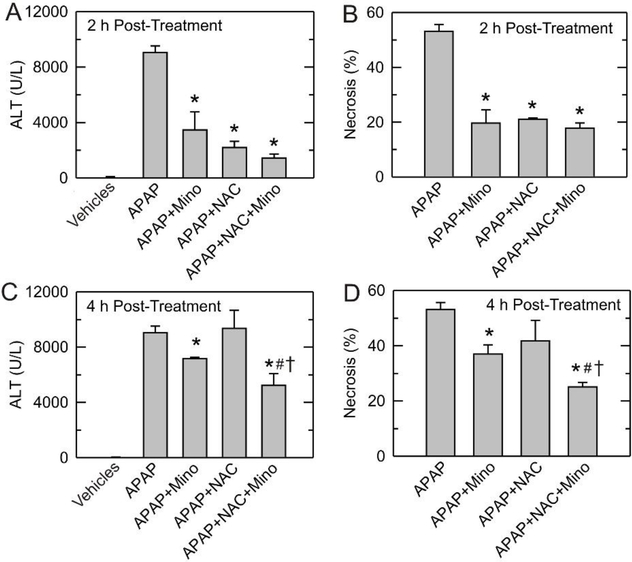

Protection by minocycline and NAC against acetaminophen-induced liver injury in vivo

To assess protection in vivo by minocycline in comparison to NAC against APAP-induced liver injury, mice were treated with APAP followed by minocycline (10 mg/kg) and/or NAC (300 mg/kg) at 2 or 4 h afterwards. At 4 h post-treatment, NAC did not decrease ALT after APAP, although NAC was protective at 2 h post-treatment (Fig. 6A and C). By comparison, minocycline given 2 or 4 h after APAP decreased ALT by 62% and 21%, respectively (p<0.05). Interestingly, minocycline plus NAC treatment after 4 h decreased ALT by 42%, indicating better protection than either minocycline or NAC alone (p<0.05) (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6. Protection by post-treatment with minocycline and NAC against AP AP-induced ALT release and hepatic necrosis in vivo.

Mice were administered 300 mg/kg APAP or vehicle. Vehicle, minocycline (10 mg/kg) and/or NAC (300 mg/kg) were given at 2 h or 4 h after APAP, as described in Materials and Methods. Serum ALT and liver necrosis were assessed 24 h after APAP. Values are means ± SE from 4 or more mice. *, p<0.05 vs vehicle; #, p<0.05 vs NAC alone; †, p<0.05 vs minocycline alone.

Liver injury was also assessed histologically at 24 h after APAP. Overdose APAP induced 53% liver necrosis at 24 h (Fig. 6B and D). After post-treatment at 2 h, minocycline, NAC and minocycline plus NAC were nearly equally protective and decreased necrosis to about 20% (Fig. 6B). After post-treatment at 4 h, NAC failed to decrease necrosis, whereas minocycline and minocycline plus NAC decreased necrosis to 37% and 25%, respectively (Fig. 6D). These results indicated that NAC alone was not effective in preventing hepatotoxicity at 4 h following APAP, but minocycline and minocycline plus NAC given 4 h after APAP still showed protection. Notably, post-treatment with minocycline plus NAC at 4 h after APAP showed better protection than either minocycline or NAC alone (p<0.05) (Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

Two transporters in the mitochondrial inner membrane, MCU and the two isoforms of mitoferrin (Mfrn1/2), play essential roles in mitochondrial transport of iron (Shaw et al., 2006; Troadec et al., 2011; Schwartz et al., 2013). Of these proteins, MCU is most important for mitochondrial iron overloading in a variety of pathological states (Uchiyama et al., 2008; Hung et al., 2013; Schwartz et al., 2013; Zhang and Lemasters, 2013; Sripetchwandee et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2016a). Under normal conditions, mitochondrial iron is utilized for the synthesis of heme and Fe-S clusters, which are important for mitochondrial respiratory enzyme activity, or is stored in mitochondrial ferritin (Lill et al., 2012). However, when the mitochondrial respiratory chain generates superoxide (O2•-) and H2O2 in excess of what can be detoxified by antioxidant systems, as occurs after glutathione depletion following APAP overdose, Fe2+ in mitochondria catalyzes OH• formation via the Fenton reaction, leading to lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction and tissue damage (Aust et al., 1985).

Much previous evidence has shown that the iron chelator, desferal, protects cultured hepatocytes after APAP, whereas addition of iron back to the incubation restores the sensitivity of hepatocytes to APAP (Adamson and Harman, 1993; Ito et al., 1994; Schnellmann et al., 1999; Kon et al., 2010). The lysosomally targeted iron chelator, starch-desferal, also decreases killing of APAP-treated cultured hepatocytes, indicating that lysosomes are a source of mobilizable chelatable iron during APAP hepatotoxicity (Kon et al., 2010).

Iron is present in respiratory enzymes as heme and iron-sulfur complexes, which are both forms of “non-chelatable” iron. Thus, iron chelators like desferal and starch-desferal do not directly remove or extract iron from the respiratory chain. Moreover, starch-desferal accumulates only into the endosomal/lysosomal compartment without access to mitochondrial iron. Chronically, iron deficiency can lead to a decline of heme and non-heme iron in respiratory enzymes as these enzymes turnover, but short term (1 h) treatment with starch-desferal is highly unlikely to alter respiratory function by this mechanism, since the half-time for turnover of respiratory enzymes is 5–6 days (Lee et al., 2018). Moreover, although iron chelation might inhibit iron-dependent respiratory enzymes to decrease mitochondrial production of O2•- and H2O2 after APAP, short term exposure (1 h) of hepatocytes to desferal and starch-desferal did not alter mitochondrial electron transport function as assessed by oxygen consumption rate (data not shown; see (Holmuhamedov et al., 2012)). Rather, acute APAP overdose itself disrupts mitochondrial respiration in vivo, leading to increased oxidative stress, decreased ATP production and hepatic necrosis (Donnelly et al., 1994; Masubuchi et al., 2005). Future studies will be needed to determine whether starch-desferal also prevents this APAP-dependent respiratory dysfunction.

Potentially, due to inhibition of mitochondrial iron chelatase that forms heme, iron chelation might cause accumulation of protoporphyrins, such as protoporphyrin IX (PPIX), a photo-sensitizing agent for photodynamic theory. However, unless a PPIX precursor like aminolevulinic acid is present, iron chelators like desferal do not increase PPIX in cultured cells after 4 h of exposure (Berg et al., 1996). Thus, it is likely that protection by starch-desferal against APAP hepatotoxicity is due directly to iron chelation rather than to a secondary effect on protoporphyrin metabolism or respiratory function.

Recently, minocycline was shown to be a mitochondrial MCU inhibitor that protects hepatocytes from chemical hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion injury both in vitro and in vivo (Schwartz et al., 2013; Kholmukhamedov et al., 2014). Minocycline also prevents cell killing and movement of iron into mitochondria after APAP, suggesting that uptake of Fe2+ into mitochondria via MCU is responsible for APAP hepatotoxicity (Hu et al., 2016a). Here, in an in vivo C57BL/6 mouse model of APAP overdose hepatotoxicity, minocycline pretreatment 1 h before APAP decreased serum ALT and liver necrosis by half. Starch-desferal afforded similar protection, consistent with the conclusion that lysosomal disruption and iron mobilization into mitochondria also occurs in vivo during APAP hepatotoxicity (Fig. 1 and 2). Although different strains of mice may have different levels of iron, the C57BL/6 mouse is an excellent APAP toxicity model, because the sensitivity to APAP overdose is similar to humans. Future studies on different strains of mice will be needed to determine how endogenous iron levels affect APAP hepatotoxicity.

The MPT is an important mechanism underlying mitochondrial dysfunction in APAP-induced hepatotoxicity (Kon et al., 2004). Previous studies show that toxic doses of APAP induce mitochondrial depolarization and inner membrane permeabilization in cultured mouse hepatocytes, which MPT inhibitors like CsA and NIM811 decrease (Kon et al., 2004; Reid et al., 2005; Kon et al., 2010). Intravital multiphoton imaging showed directly that mitochondrial depolarization occurs in vivo in mouse livers after APAP overdose (Fig. 4B). Similar to previous results that minocycline inhibits MPT onset in vivo after orthotopic rat liver transplantation and mouse hemorrhagic shock (Theruvath et al., 2008; Czerny et al., 2012) and that starch-desferal inhibits the MPT and cell death in vitro in hepatocytes during APAP hepatotoxicity, oxidative stress and ischemia/reperfusion (Zhang and Lemasters, 2013; Hu et al., 2016a), we found that starch-desferal and minocycline decreased mitochondrial depolarization and cell death in vivo after APAP in the mouse model (Fig. 4C and D). These results suggest that the MPT is likely triggered by iron uptake into mitochondria through MCU during APAP hepatotoxicity.

Tetracycline is an antibiotic similar to minocycline, but which does not inhibit MCU. In ischemia/reperfusion injury during liver transplantation and hemorrhage and resuscitation, tetracycline does not protect against liver injury (Theruvath et al., 2008; Czerny et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 2013). Similarly, in the present study, tetracycline did not protect significantly against APAP-induced ALT release, liver necrosis and mitochondrial depolarization (Fig. 1 and data not shown), suggesting strongly that minocycline protection against APAP hepatotoxicity is mediated by MCU inhibition. After APAP overdose, the rate of glutathione depletion parallels that of NAPQI formation. Here, the time course and extent of hepatic glutathione depletion after APAP were virtually identical with and without minocycline, indicating that minocycline does not inhibit bioactivation of APAP to NAPQI (Fig. 3). Thus, the protection against liver injury and mitochondrial dysfunction by minocycline was likely due to inhibition of iron mobilization into mitochondria via MCU rather than prevention of APAP activation to NAPQI and glutathione depletion.

The ultimate goal of this research was to develop new translatable clinical strategies to minimize liver injury after APAP overdose. The formation of NAPQI, which first depletes glutathione and then subsequently causes protein adduct formation, is a critical event in APAP hepatotoxicity (Zimmerman and Maddrey, 1995). N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a glutathione precursor, which promotes hepatic glutathione synthesis and supports the detoxification of NAPQI (Lauterburg et al., 1983; Corcoran et al., 1985). Accordingly, the glutathione precursor NAC was introduced to treat patients with APAP overdose in the 1970s and remains the preferred therapeutic option for APAP overdose patients. NAC is most effective when given as early as possible after APAP intoxication, and therapeutic efficacy decreases when NAC is administered more than 8 h after APAP poisoning (Whyte et al., 2007). In mice, protection is lost when NAC is given later than 2 h after APAP overdose (Salminen et al., 1998; James et al., 2003b), which the present results confirm (Fig. 6). Previously, an important role of iron in APAP toxicity was shown by the observation that the iron chelator, desferal, administered to mice 1 h after APAP decreased hepatotoxicity without altering covalent adduct formation (Schnellmann et al., 1999). Here, we compared individual post-treatments with minocycline and NAC against APAP-induced liver injury. NAC post-treatment 4 hours after APAP failed to protect, whereas minocycline provided some protection (Fig. 6A and B). However, the combination of minocycline plus NAC at 4 h post-treatment provided better protection against ALT release and liver necrosis than minocycline or NAC alone (Fig. 6A and B). These results may be explained by the different principles of protection by NAC and minocycline. NAC replenishes glutathione, whereas minocycline prevents iron translocation into mitochondria. In cultured mouse hepatocytes, glutathione depletion is maximal at 2 h after APAP (Kon et al., 2004). However, lysosomal iron mobilization via MCU occurs beginning after about 4 h of APAP exposure, which then promotes the MPT and cell killing (Kon et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2016a). Since the Fe2+-dependent MPT is downstream of glutathione depletion after APAP, minocycline may prevent liver injury through inhibition of iron mobilization into mitochondria via MCU at later time points after APAP than NAC. Moreover, since minocycline and NAC act via different mechanisms, their protection is synergistic.

Notably, minocycline plus NAC is more effective than NAC or minocycline alone in treatment of APAP hepatotoxicity both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 5 and 6). Some time for glutathione re-synthesis is required for NAC to be fully effective. By contrast, inhibition of iron movement into mitochondria by minocycline should occur immediately upon MCU blockade, which means minocycline provides protection more rapidly than NAC. Alternatively, glutathione replenishment by NAC may decrease oxidative stress not related to the iron-catalyzed Fenton reaction. Possibly for these reasons, minocycline plus NAC treatment showed better protection than NAC or minocycline alone. Minocycline causes an autoimmune-like hepatotoxicity, but, no hepatotoxicity is associated with short term use (Lawrenson et al., 2000; Urban et al., 2017). Nonetheless, any future human studies will have to take into consideration potential adverse effects of minocycline.

In conclusion, our results indicate that mobilization of chelatable iron from damaged lysosomes into mitochondria via MCU plays a key role in APAP-induced liver injury in vivo. The protection by minocycline post-treatment against APAP hepatotoxicity suggests its clinical benefit, especially in combinations with current therapies using NAC. Future clinical trials will be needed to validate such clinical use.

Highlights.

During acetaminophen (APAP) hepatotoxicity, damaged lysosomes release iron.

Fe2+ enters mitochondria by the calcium uniporter to catalyze toxic ROS formation.

Minocycline blocks the uniporter and protects against APAP hepatotoxicity.

In vivo, minocycline posttreatment after APAP protects better than N-acetylcysteine.

Minocycline plus NAC protects at longer times after APAP than NAC alone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by Grants DK073336, DK037034, T32DK083262, AA021191, AA025379, and DK102142 from the National Institutes of Health. Imaging facilities were supported, in part, by P30 CA138313, 5 P20 GM103542-03 and 1 S10 OD018113 with animal facility support from Grant C06 RR015455.

Abbreviations

- •OH

hydroxyl radical

- ΔΨ

membrane potential

- APAP

acetaminophen

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- HDM

hormonally defined medium

- MCU

mitochondrial Ca2+ Fe2+ uniporter

- MPT

mitochondrial permeability transition

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- NAPQI

N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine

- PI

propidium iodide

- Rh123

rhodamine 123

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adamson GM, Harman AW, 1993. Oxidative stress in cultured hepatocytes exposed to acetaminophen. Biochem Pharmacol 45, 2289–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade RJ, Tulkens PM, 2011. Hepatic safety of antibiotics used in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother 66, 1431–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aras M, Altas M, Motor S, Dokuyucu R, Yilmaz A, Ozgiray E, Seraslan Y, Yilmaz N, 2015. Protective effects of minocycline on experimental spinal cord injury in rats. Injury 46, 1471–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aust SD, Morehouse LA, Thomas CE, 1985. Role of metals in oxygen radical reactions. J Free Radic Biol Med 1, 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Knight TR, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H, 2004. Acetaminophen-induced oxidant stress and cell injury in cultured mouse hepatocytes: protection by N-acetyl cysteine. Toxicol Sci 80, 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg K, Anholt H, Bech O, Moan J, 1996. The influence of iron chelators on the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in 5-aminolaevulinic acid-treated cells. Br J Cancer 74, 688–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burcham PC, Harman AW, 1991. Acetaminophen toxicity results in site-specific mitochondrial damage in isolated mouse hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 266, 5049–5054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Aleksa K, Woodland C, Rieder M, Koren G, 2008. N-Acetylcysteine prevents ifosfamide-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Br J Pharmacol 153, 1364–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu HC, Lin YL, Sytwu HK, Lin SH, Liao CL, Chao YC, 2005. Effects of minocycline on Fas-mediated fulminant hepatitis in mice. Br J Pharmacol 144, 275–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran GB, Racz WJ, Smith CV, Mitchell JR, 1985. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on acetaminophen covalent binding and hepatic necrosis in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 232, 864–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerny C, Kholmukhamedov A, Theruvath TP, Maldonado EN, Ramshesh VK, Lehnert M, Marzi I, Zhong Z, Lemasters JJ, 2012. Minocycline decreases liver injury after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation in mice. HPB Surg 2012, 259512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly PJ, Walker RM, Racz WJ, 1994. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration in vivo is an early event in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Arch Toxicol 68, 110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatmark T, Romslo I, 1975. Energy-dependent accumulation of iron by isolated rat liver mitochondria. Requirement of reducing equivalents and evidence for a unidirectional flux of Fe(II) across the inner membrane. J Biol Chem 250, 6433–6438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana RJ, 2008. Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am 92, 761–794, viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghate NB, Chaudhuri D, Das A, Panja S, Mandal N, 2015. An Antioxidant Extract of the Insectivorous Plant Drosera burmannii Vahl. Alleviates Iron-Induced Oxidative Stress and Hepatic Injury in Mice. PLoS One 10, e0128221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Chen Q, Tang J, Zhang J, Tao Y, Li L, Zhu G, Feng H, Chen Z, 2015. Minocycline-induced attenuation of iron overload and brain injury after experimental germinal matrix hemorrhage. Brain Res 1594, 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa N, Shinohara M, Saberi B, Gaarde WA, Han D, Kaplowitz N, 2008. Role of JNK translocation to mitochondria leading to inhibition of mitochondria bioenergetics in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J Biol Chem 283, 13565–13577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmatz P, Grady RW, Dragsten P, Vichinsky E, Giardina P, Madden J, Jeng M, Miller B, Hanson G, Hedlund B, 2007. Phase Ib clinical trial of starch-conjugated deferoxamine (40SD02): a novel long-acting iron chelator. Br J Haematol 138, 374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Kholmukhamedov A, Lindsey CC, Beeson CC, Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ, 2016a. Translocation of iron from lysosomes to mitochondria during acetaminophen-induced hepatocellular injury: Protection by starch-desferal and minocycline. Free Radic Biol Med 97, 418–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Ramshesh VK, McGill MR, Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ, 2016b. Low Dose Acetaminophen Induces Reversible Mitochondrial Dysfunction Associated with Transient c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Activation in Mouse Liver. Toxicol Sci 150, 204–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung HI, Schwartz JM, Maldonado EN, Lemasters JJ, Nieminen AL, 2013. Mitoferrin-2-dependent mitochondrial iron uptake sensitizes human head and neck squamous carcinoma cells to photodynamic therapy. J Biol Chem 288, 677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Suzuki Y, Ogonuki H, Hiraishi H, Razandi M, Terano A, Harada T, Ivey KJ, 1994. Role of iron and glutathione redox cycle in acetaminophen-induced cytotoxicity to cultured rat hepatocytes. Dig Dis Sci 39, 1257–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, 1990. Glutathione disulfide formation and oxidant stress during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice in vivo: the protective effect of allopurinol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 255, 935–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LP, Mayeux PR, Hinson JA, 2003a. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab Dispos 31, 1499–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LP, McCullough SS, Lamps LW, Hinson JA, 2003b. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on acetaminophen toxicity in mice: relationship to reactive nitrogen and cytokine formation. Toxicol Sci 75, 458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KJ, Sutton TA, Weathered N, Ray N, Caldwell EJ, Plotkin Z, Dagher PC, 2004. Minocycline inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in a rat model of ischemic renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287, F760–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholmukhamedov A, Czerny C, Hu J, Schwartz J, Zhong Z, Lemasters JJ, 2014. Minocycline and doxycycline, but not tetracycline, mitigate liver and kidney injury after hemorrhagic shock/resuscitation. Shock 42, 256–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Qian T, Lemasters JJ, 2003. Mitochondrial permeability transition in the switch from necrotic to apoptotic cell death in ischemic rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 124, 494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon K, Kim JS, Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ, 2004. Mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis of cultured mouse hepatocytes. Hepatology 40, 1170–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon K, Kim JS, Uchiyama A, Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ, 2010. Lysosomal iron mobilization and induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced toxicity to mouse hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci 117, 101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz T, Terman A, Brunk UT, 2007. Autophagy, ageing and apoptosis: the role of oxidative stress and lysosomal iron. Arch Biochem Biophys 462, 220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterburg BH, Corcoran GB, Mitchell JR, 1983. Mechanism of action of N-acetylcysteine in the protection against the hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen in rats in vivo. J Clin Invest 71, 980–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrenson RA, Seaman HE, Sundstrom A, Williams TJ, Farmer RD, 2000. Liver damage associated with minocycline use in acne: a systematic review of the published literature and pharmacovigilance data. Drug Saf 23, 333–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill R, Hoffmann B, Molik S, Pierik AJ, Rietzschel N, Stehling O, Uzarska MA, Webert H, Wilbrecht C, Muhlenhoff U, 2012. The role of mitochondria in cellular iron-sulfur protein biogenesis and iron metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823, 1491–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masubuchi Y, Suda C, Horie T, 2005. Involvement of mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. J Hepatol 42, 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill MR, Lebofsky M, Norris HR, Slawson MH, Bajt ML, Xie Y, Williams CD, Wilkins DG, Rollins DE, Jaeschke H, 2013. Plasma and liver acetaminophen-protein adduct levels in mice after acetaminophen treatment: dose-response, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 269, 240–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JR, Jollow DJ, Potter WZ, Davis DC, Gillette JR, Brodie BB, 1973a. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. I. Role of drug metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 187, 185–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JR, Jollow DJ, Potter WZ, Gillette JR, Brodie BB, 1973b. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. IV. Protective role of glutathione. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 187, 211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moles A, Torres S, Baulies A, Garcia-Ruiz C, Fernandez-Checa JC, 2018. Mitochondrial-Lysosomal Axis in Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity. Front Pharmacol 9, 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah GK, Salem R, Da’as S, Al-Jamal OLA, Scott M, Mustafa I, 2019. Biocompatibility and toxicity of novel iron chelator Starch-Deferoxamine (S-DFO) compared to zinc oxide nanoparticles to zebrafish embryo: An oxidative stress based apoptosis, physicochemical and neurological study profile. Neurotoxicol Teratol 72, 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotera P, Rundgren M, Porubek DJ, Cotgreave I, Moldeus P, Orrenius S, Nelson SD, 1989. On the role of Ca2+ in the toxicity of alkylating and oxidizing quinone imines in isolated hepatocytes. Chem Res Toxicol 2, 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen AL, Gores GJ, Bond JM, Imberti R, Herman B, Lemasters JJ, 1992. A novel cytotoxicity screening assay using a multiwell fluorescence scanner. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 115, 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucheu S, Coudray C, Tresallet N, Favier A, de Leiris J, 1993. Effect of iron overload in the isolated ischemic and reperfused rat heart. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 7, 701–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran A, Visschers RGJ, Duan L, Akakpo JY, Jaeschke H, 2018. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a mechanism of drug-induced hepatotoxicity: current understanding and future perspectives. J Clin Transl Res 4, 75–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid AB, Kurten RC, McCullough SS, Brock RW, Hinson JA, 2005. Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity: role of oxidative stress and mitochondrial permeability transition in freshly isolated mouse hepatocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312, 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito C, Zwingmann C, Jaeschke H, 2010. Novel mechanisms of protection against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in mice by glutathione and N-acetylcysteine. Hepatology 51, 246–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen WF Jr., Voellmy R, Roberts SM, 1998. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on heat shock protein induction by acetaminophen in mouse liver. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 286, 519–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnellmann JG, Pumford NR, Kusewitt DF, Bucci TJ, Hinson JA, 1999. Deferoxamine delays the development of the hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen in mice. Toxicol Lett 106, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J, Holmuhamedov E, Zhang X, Lovelace GL, Smith CD, Lemasters JJ, 2013. Minocycline and doxycycline, but not other tetracycline-derived compounds, protect liver cells from chemical hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibition of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 273, 172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GC, Cope JJ, Li L, Corson K, Hersey C, Ackermann GE, Gwynn B, Lambert AJ, Wingert RA, Traver D, Trede NS, Barut BA, Zhou Y, Minet E, Donovan A, Brownlie A, Balzan R, Weiss MJ, Peters LL, Kaplan J, Zon LI, Paw BH, 2006. Mitoferrin is essential for erythroid iron assimilation. Nature 440, 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Rehman H, Ramshesh VK, Schwartz J, Liu Q, Krishnasamy Y, Zhang X, Lemasters JJ, Smith CD, Zhong Z, 2012. Sphingosine kinase-2 inhibition improves mitochondrial function and survival after hepatic ischemia-reperfusion. J Hepatol 56, 137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripetchwandee J, KenKnight SB, Sanit J, Chattipakorn S, Chattipakorn N, 2014. Blockade of mitochondrial calcium uniporter prevents cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction caused by iron overload. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 210, 330–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theruvath TP, Zhong Z, Pediaditakis P, Ramshesh VK, Currin RT, Tikunov A, Holmuhamedov E, Lemasters JJ, 2008. Minocycline and N-methyl-4-isoleucine cyclosporin (NIM811) mitigate storage/reperfusion injury after rat liver transplantation through suppression of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Hepatology 47, 236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troadec MB, Warner D, Wallace J, Thomas K, Spangrude GJ, Phillips J, Khalimonchuk O, Paw BH, Ward DM, Kaplan J, 2011. Targeted deletion of the mouse Mitoferrin1 gene: from anemia to protoporphyria. Blood 117, 5494–5502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama A, Kim JS, Kon K, Jaeschke H, Ikejima K, Watanabe S, Lemasters JJ, 2008. Translocation of iron from lysosomes into mitochondria is a key event during oxidative stress-induced hepatocellular injury. Hepatology 48, 1644–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban TJ, Nicoletti P, Chalasani N, Serrano J, Stolz A, Daly AK, Aithal GP, Dillon J, Navarro V, Odin J, Barnhart H, Ostrov D, Long N, Cirulli ET, Watkins PB, Fontana RJ, Drug-Induced Liver Injury N., Pharmacogenetics of Drug-Induced Liver Injury, g., International Serious Adverse Events, C., 2017. Minocycline hepatotoxicity: Clinical characterization and identification of HLA-B *35:02 as a risk factor. J Hepatol 67, 137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BL, Richie JP Jr., 1993. Fasting-induced depletion of glutathione in the aging mouse. Biochem Pharmacol 46, 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RM, Racz WJ, McElligott TF, 1980. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Lab Invest 42, 181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhu S, Drozda M, Zhang W, Stavrovskaya IG, Cattaneo E, Ferrante RJ, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM, 2003. Minocycline inhibits caspase-independent and - dependent mitochondrial cell death pathways in models of Huntington’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 10483–10487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YQ, Wang MY, Fu XR, Peng Y, Gao GF, Fan YM, Duan XL, Zhao BL, Chang YZ, Shi ZH, 2015. Neuroprotective effects of ginkgetin against neuroinjury in Parkinson’s disease model induced by MPTP via chelating iron. Free Radic Res 49, 1069–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte IM, Francis B, Dawson AH, 2007. Safety and efficacy of intravenous N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose: analysis of the Hunter Area Toxicology Service (HATS) database. Curr Med Res Opin 23, 2359–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn CC, 1995. Toxicity of iron and hydrogen peroxide: the Fenton reaction. Toxicol Lett 82–83, 969–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Woolbright BL, Kos M, McGill MR, Dorko K, Kumer SC, Schmitt TM, Jaeschke H, 2015. Lack of Direct Cytotoxicity of Extracellular ATP against Hepatocytes: Role in the Mechanism of Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity. J Clin Transl Res 1, 100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Lemasters JJ, 2013. Translocation of iron from lysosomes to mitochondria during ischemia predisposes to injury after reperfusion in rat hepatocytes. Free Radic Biol Med 63, 243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Stavrovskaya IG, Drozda M, Kim BY, Ona V, Li M, Sarang S, Liu AS, Hartley DM, Wu DC, Gullans S, Ferrante RJ, Przedborski S, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM, 2002. Minocycline inhibits cytochrome c release and delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Nature 417, 74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman HJ, Maddrey WC, 1995. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) hepatotoxicity with regular intake of alcohol: analysis of instances of therapeutic misadventure. Hepatology 22, 767–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]