Highlights

-

•

Reduced montages with subdermal single-use EEG needle electrodes may be used in comatose COVID-19 patients.

-

•

Full 10-20 EEG placement with an ECG derivation remains the standard.

-

•

Note if the patient undergoes prone positioning, note the patient and head position, along with patterns of breathing.

Keywords: COVID-19, EEG, ICU, Coma, Prone position

Abstract

There are questions and challenges regarding neurologic complications in COVID-19 patients. EEG is a safe and efficient tool for the evaluation of brain function, even in the context of COVID-19. However, EEG technologists should not be put in danger if obtaining an EEG does not significantly advance diagnosis or change management in the patient. Not every neurologic problem stems from a primary brain injury: confusion, impaired consciousness that evolves to stupor and coma, and headaches are frequent in hypercapnic/hypoxic encephalopathies. In patients with chronic pulmonary disorders, acute symptomatic seizures have been reported in acute respiratory failure in 6%. The clinician should be aware of the various EEG patterns in hypercapnic/hypoxic and anoxic (post-cardiac arrest syndrome) encephalopathies as well as encephalitides. In this emerging pandemic of infectious disease, reduced EEG montages using single-use subdermal EEG needle electrodes may be used in comatose patients. A full 10–20 EEG complement of electrodes with an ECG derivation remains the standard. Under COVID-19 conditions, an expedited study that adequately screens for generalized status epilepticus, most types of regional status epilepticus, encephalopathy or sleep may serve for most clinical questions, using simplified montages may limit the risk of infection to EEG technologists. We recommend noting whether the patient is undergoing or has been placed prone, as well as noting the body and head position during the EEG recording (supine versus prone) to avoid overinterpretation of respiratory, head movement, electrode, muscle or other artifacts. There is slight elevation of intracranial pressure in the prone position. In non-comatose patients, the hyperventilation procedure should be avoided. At present, non-specific EEG findings and abnormalities should not be considered as being specific for COVID-19 related encephalopathy.

1. Introduction

EEG provides a readily available, safe, and effective means of evaluating brain function. Despite recent advances in neuroimaging, EEG remains essential in monitoring in neurology, especially in acute neurological conditions seen in the intensive care unit (ICU). With the current COVID-19 pandemic, there is increasing interest in the neurologic complications in these patients. Anosmia and dysgeusia, recently described (Lechien et al., 2020, Xydakis et al., 2020), suggest the invasion of the olfactory nerve and the consequent risk of spread throughout the brain. Several human respiratory viruses are neurotropic and neuroinvasive, and it has been reported that the coronavirus family have a tropism for the CNS (Desforges et al., 2019). For COVID-19 patients, considering the current and expected evolution of the pandemic, updated and relevant appropriate practical guidelines for EEG recordings are warranted.

2. Technical recommendations

Cup or disk electrodes are commonly used in ICU for continuous EEG monitoring, but with infected comatose patients, brief recordings with reduced electrode montages using single-use subdermal EEG needle electrodes should be considered. These pose no problem with decontamination, and they do not require scalp abrasion. Above all, they can be applied rapidly (Caricato et al., 2018, Hopp and Atallah, 2018). Disadvantages include higher impedance (Hopp and Atallah, 2018), the risk of needlestick injury, and cost.

A full 10–20 EEG complement of electrodes with an ECG derivation remains the standard. Three temporal electrodes over each hemisphere are essential for evaluation of the temporal lobe and the inferior part of the frontal lobe. Reduced montages may result in difficulties in identifying artifacts, and especially in the failure to recognize lateralized periodic discharges (LPDs) of the temporal lobe or the inferior part of the frontal lobe. In cases of suspected encephalitis, assuming the involvement of the olfactory nerves, the site of predilection for LPDs is likely to be the temporal lobes, as in herpes simplex virus (HSV). Under COVID-19 conditions, an expedited study that adequately screens for generalized status epilepticus, most types of regional status epilepticus, encephalopathy or sleep may serve for most clinical questions, using simplified montages may limit the risk of infection to EEG technologists.

The EEG technologist should note the position of the patient’s head and body, relaxation of the head and neck muscles and the possible sources of extraneous electrical and medical device artifact. Concomitant video-recording is strongly recommended (see below). A prone (face-down) position is used for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome to improve oxygenation with an average number of sessions of 4 (Guérin et al., 2013), and patients may stay on their stomachs for 16 hours a day (WHO, 2020a). This procedure may require an increase in muscle relaxants or in sedation (Roche-Campo et al., 2011), which could result in a more prolonged ICU stay. The prone position is rarely encountered by electroencephalographers (EEGer), and may result in difficulties in recognizing artifacts commonly seen in the posterior electrodes: in the supine position, occipital electrodes are particularly vulnerable to numerous artifacts, such as contact with the bed/pillow. When prone, these artifacts would be seen in the frontopolar leads that are in contact with the bed.

Prone positioning effects on the EEG in adults for periods of 16 hours per day are unknown. There is a moderate elevation of intracranial pressure during prone positioning (Roth et al., 2014), which is contraindicated in cases of raised intracranial pressure > 30 mmHg or cerebral perfusion pressure < 60 mmHg (Malhotra and Kacmarek, 2020).

During mechanical ventilation, respiration artifacts are common (Tatum, 2018). Ventilator-triggered artifacts consist of periodic activities typically at about 20 breaths per minute, at regular intervals. In COVID-19 patients, the respiratory rate may be higher (WHO, 2020b), and should be checked by the EEG technologist and noted in the report. Irregular breath intervals are possible when the patient is not on the ventilator (Rampal et al., 2018). These slight head movements produce waveforms that are seen over the posterior head regions (Tatum, 2018), but periodic frontally dominant waveforms may be seen (Rampal et al., 2018). Waveforms can be asymmetric. Water condensation within the tubing connected to the ventilator may produce artifacts that simulate intermittent polysharp-waves (Tatum et al., 2011), and may appear to be lateralized if the ventilator connections lie in close proximity to the anterior head regions, mimicking LPDs (Tatum et al., 2011). Yoo et al. reported one patient with irregular bursts of sharp activity time-locked to a gurgling sound independent of the ventilator rate due to movement of fluids within the upper respiratory tracts and/or the tube (Yoo et al., 2014).

Ballistocardiographic artifacts are more unusual. These result from movements of the head/body synchronous to cardiac activity (pulsatile force on the aortic arch) (Stern, 2015). As it is a result of a slight movement of the head, this peculiar “pulse” artifact is also mainly seen on the posterior electrodes in contact with the bed in the supine position. The ECG helps identify this artifact. There are also many environmental/electric artifacts in ICU, such as 50/60-Hz notch interferences.

EEG reactivity to auditory and nociceptive stimuli should be tested. In comatose patients, the absence of EEG reactivity is usually associated with poor outcome (Rossetti et al., 2017, André-Obadia et al., 2018), and this probably also applies to comatose COVID-19 patients, especially if these are not deeply sedated. In cases of confusional states versus an isolated impairment of vigilance, reactivity can help differentiate metabolic/toxic/respiratory encephalopathies from nonconvulsive status epilepticus (Gélisse et al., 2019, Kaplan et al., 2020) (Table 1 ). In non-comatose patients, hyperventilation is not useful and should be not performed, as it may lead to cerebral vasoconstriction that can be potentially challenging for brain perfusion.

Table 1.

Absence status epilepticus versus metabolic/toxic encephalopathies. The five key questions.

| Question 1 | Is it a confusional state or only a problem of vigilance? |

| Question 2 | Is there a fluctuation of symptoms or change in consciousness from somnolence to coma? |

| Question 3 | Is the EEG activity rhythmic or periodic? |

| Question 4 | Is the EEG activity dynamic, showing spatiotemporal evolution, or relatively monomorphic? |

| Question 5 | Is the EEG reactive to stimuli, wakefulness, sleep, arousal, or antiseizure drugs*? |

Only consider an IV benzodiazepine test positive if both EEG and consciousness normalize.

Simultaneous video recording is strongly advised. This is not a specific recommendation for COVID-19 patients, but video recording in this situation may help see the position of the body (supine versus prone position) and the position of the head (version to the right or to the left). Simultaneous video-EEG recording enables clinical correlations and can help to identify some artifacts with video and audio recordings (Yoo et al., 2014).

3. Recommendations for the electroencephalographers

The clinical context, vital signs, drugs used, results of neuroimaging, and metabolic blood tests should be available.

In COVID-19 patients, arterial-blood gas tests, and cardiac low-flow/no-flow events are important.

Age of the patients and the medical history help with the interpretation of the EEG. For example, vulnerability to metabolic encephalopathies increases with age and cortical/subcortical disease (Gélisse et al., 2019). In advanced Alzheimer’s disease, periodic complexes occasionally occur, but without anterior predominance (Gélisse et al., 2019). Furthermore, elderly people also have increasing impairment of renal function contributing to delayed drug excretion. There is a high prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome, such as COVID-19 (Simonnet et al., 2020). Obesity in the critically ill increases the risk of complications in several organ systems (Schetz et al., 2019).

American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (ACNS) recommendation for EEG scoring in ICU should be used (2012) (Hirsch et al., 2013); these have been validated and allow easy generalization of EEG findings (Gaspard et al., 2014).

Electroencephalographers should have a solid knowledge of EEG patterns seen in the ICU, e.g., anoxic (post-cardiac arrest syndrome), toxic, metabolic, sepsis, and hypercapnic/hypoxic encephalopathies (Kaplan and Rossetti, 2011, Bauer et al., 2013, Stern, 2015, Gélisse et al., 2019, Kaplan et al., 2020). Etiologies may be mixed (Fig. 1 ). Sharp waves with triphasic appearance are by no means specific to metabolic disorders and can be observed in respiratory failure, especially in case of respiratory tract infection (Laxenaire et al., 1970; Sutter et al., 2013) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ). Sometimes, EEGs of patients with metabolic/toxic encephalopathy are striking, and nonconvulsive status epilepticus may be part of the differential diagnosis: there are five key questions that should be routinely considered in this case (Table 1) (Gélisse et al., 2019, Kaplan et al., 2020).

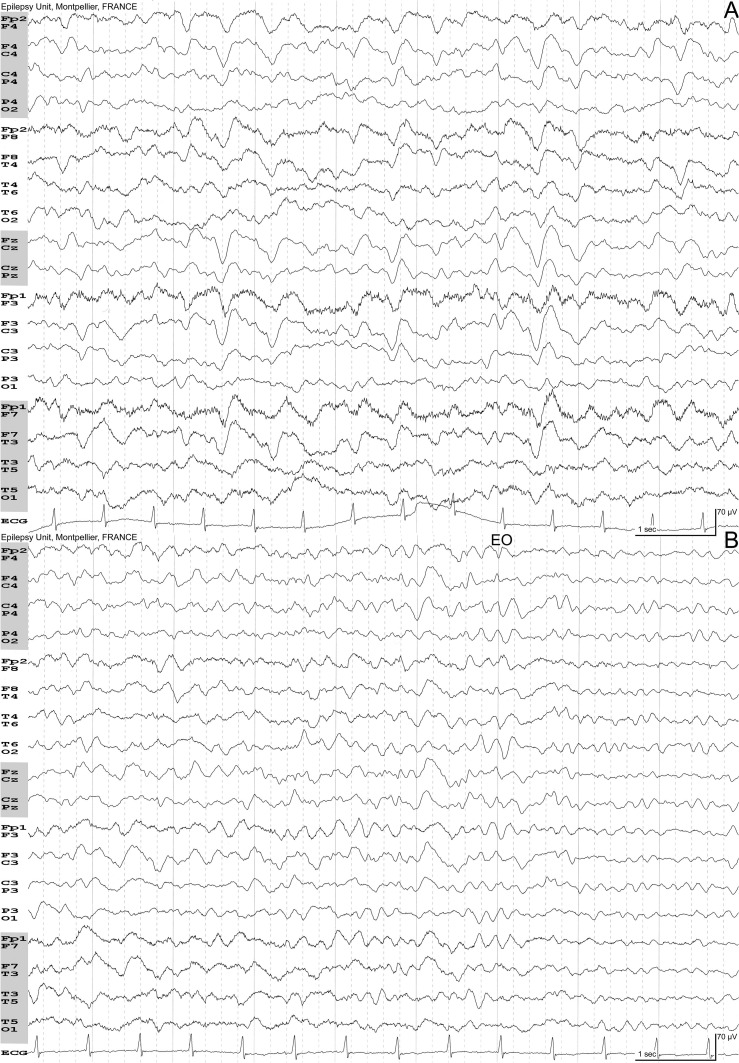

Fig. 1.

Mixed-type encephalopathy (respiratory + sepsis + metabolic). 81-year-old woman. Flu followed by severe acute respiratory syndrome in the context of bacterial pneumonia. Stupor. Arterial blood gas: PaO2 74 mmHg, PaCO2 33 mmHg, pH 7.51, Hb 9.7 g/L. Acute renal failure with serum creatinine of 208 μmol/L. High C-Reactive Protein (174.6 mg/L). A: Eyes closed, drowsy. Bilateral delta waves with anterior predominance. Some triphasic waves can be seen. B: Few seconds later, the patient is more reactive. Note the reactivity to eyes opening (EO). Full recovery 15 days later.

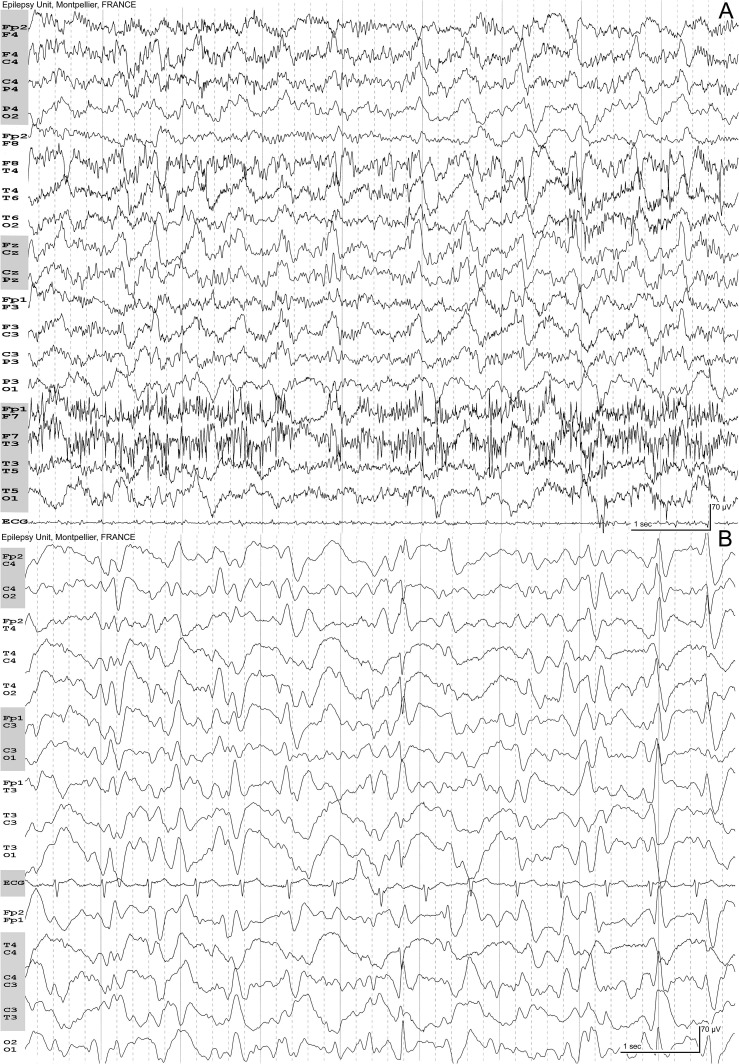

Fig. 2.

A, hypercapnic encephalopathy syndrome: 65-year-old man with a previous history of left pneumonectomy. Impairment of vigilance, mutism. At admittance, the day of the EEG, PaCO2 127 mmHg, PaO2 134 mmHg, pH 7.15, natremia 151 mmol/L, serum creatinine 55 μmol/L. The EEG shows numerous muscular artifacts, especially on the left temporal region. Eyes are open. Periodic paroxysms with a variable interval. The activity is diffuse. The paroxysms have no typical triphasic morphology. B, hypoxemia: 56-year-old woman, impaired vigilance. Arterial blood gas: PaO2 48 mmHg, PaCO2 38 mmHg, pH 7.47, Hb 8.4 g/L. No metabolic change. The EEG shows diffuse periodic activity with triphasic morphology, sharply contoured at the end of the plate.

Among COVID-19 patients with significant clinical symptoms, about 15% experienced severe symptoms (respiratory rate ≥ 30/min, dyspnea, SaO2 ≤ 93%), and 5% are critical (respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction or failure) (Clerkin et al., 2019). Cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes mellitus are common comorbidities in patients with COVID-19 (Yang et al., 2020) as is obesity (Simonnet et al., 2020). Of 138 hospitalized patients, major complications included acute respiratory distress syndrome (19.6%), arrhythmia (16.7%), and shock (8.7%) (Wang et al., 2019). Baldi et al. compared out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (February 21 through March 31, 2020) with the same period in 2019 using the Lombardia Cardiac Arrest Registry, and found a 58% increase, and that the cumulative incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was strongly associated with the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 (Baldi et al., 2020). EEG patterns in anoxic-ischemic encephalopathies are well known, from Generalized Periodic Discharges to burst-suppression and silence (see review in Bauer et al., 2013), but prognostication in some patients may prove challenging (Rossetti et al., 2017, Ruijter et al., 2019, Bongiovanni et al., 2020).

Respiratory encephalopathies are more often the consequence of hypercapnia than hypoxemia. Patients exhibit drowsiness, asterixis, and headaches that progress to confusion, drowsiness, and coma. The EEG is not specific, with background slowing progressing to discontinuous patterns and burst-suppression. Triphasic waves, as mentioned above, may occur. The degradation of the EEG parallels the deterioration of consciousness. Laxenaire-Aug et al. investigated 70 patients with chronic lung diseases hospitalized for acute respiratory failure (SaO2 ≤ 70%; PaCO2 > 60 mmHg) (Laxenaire-Aug et al., 1970). Acute symptomatic seizures were present in four cases (6%). Headaches were frequent (33%) with occipital predominance, and worse in the morning. These authors classified the EEG in four grades. Grade 1: Alpha rhythm at 8 Hz with some isolated theta waves. The reactivity to eye-opening was good. Grade 2: Background with theta frequencies, incomplete reactivity to eye-opening, bursts of symmetrical, irregular, high-voltage delta waves over the frontotemporal regions. Grade 3: No reactivity to eye-opening. Frequent bursts of anterior delta waves. These can be sharp. Grade 4: Persistent diffuse delta activity. No clear-cut correlation was found between the EEG categories and blood gases (PaCO2, pH, SaO2), but in this older study, an increased severity of the EEG grade corresponded to a significant fall in cerebrospinal fluid pH. These authors also found macular edema in five patients (7%) with poor prognosis. Even when the EEG had periodic suppression, a fatal prognosis was not invariable. The authors noted the earlier heralding of deterioration with worsening EEG.

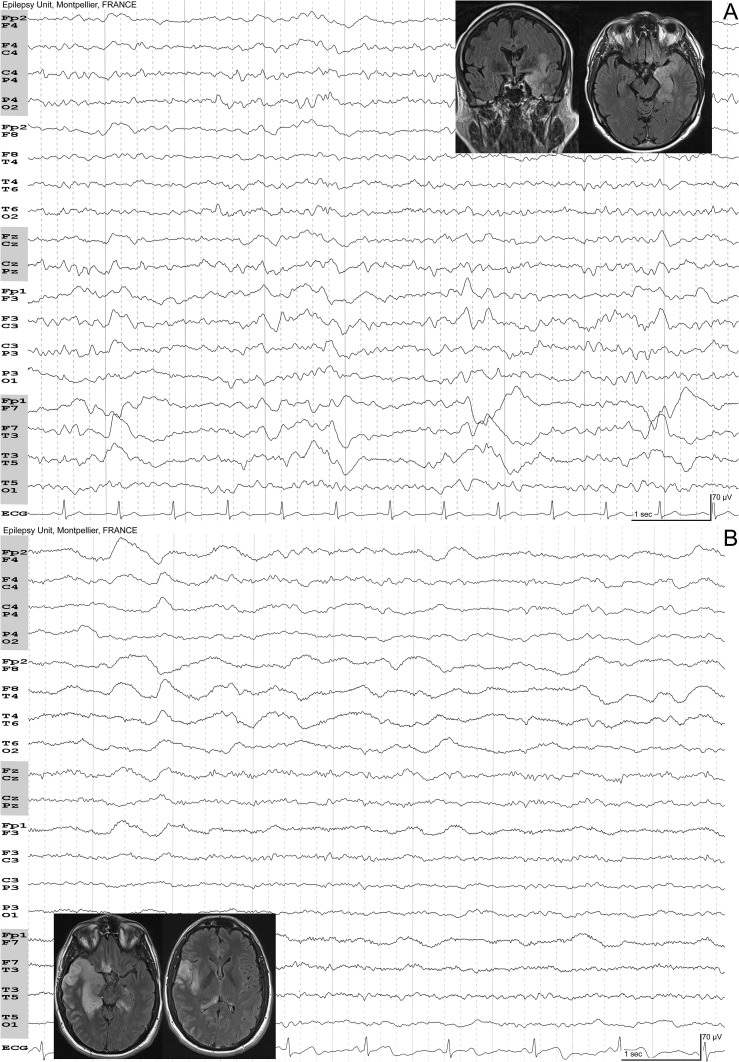

Infectious encephalitides may show LPDs with periodicity of less of four seconds (so called “short periods”) (Gaches, 1971, Dunand and Jallon, 2002). These are suggestive of HSV encephalitis, but can also be seen in other viral etiologies, e.g., herpes virus-6 limbic encephalitis (Gélisse et al., 2019). In HSV encephalitis, these LPDs are seen over the temporal lobes and can spread to the homolateral frontal lobe (Fig. 3 ). In early stages, there is slow polymorphic unilateral delta activity (Dunand and Jallon, 2002). Periodic activities appear early in the course of disease and typically disappear after 15 days, replaced by diffusely abnormal patterns, when pathology may reveal widespread necrosis (Gaches et al., 1978). EEG is thus helpful in identifying patterns of periodic discharges, subclinical seizures, non-convulsive status epilepticus, focal slowing (e.g., with strokes), and delayed recovery from anesthesia (sleep patterns).

Fig. 3.

A, herpes simplex encephalitis: 61-year-old man. Confusion. Fever. Eyes closed. Lateralized periodic discharges over the left temporal region. B, Herpes simplex encephalitis: 35-year-old man. Unusual headache for ten days and low-grade fever. Polymorphic delta activity over the right temporal lobe that spreads to the right frontal lobe. There is no periodic activity, maybe because of the subclinical evolution. Insets show fluid attenuated inversion recovery MRIs of the patients with typical mesiotemporal T2w signal hyperintensity.

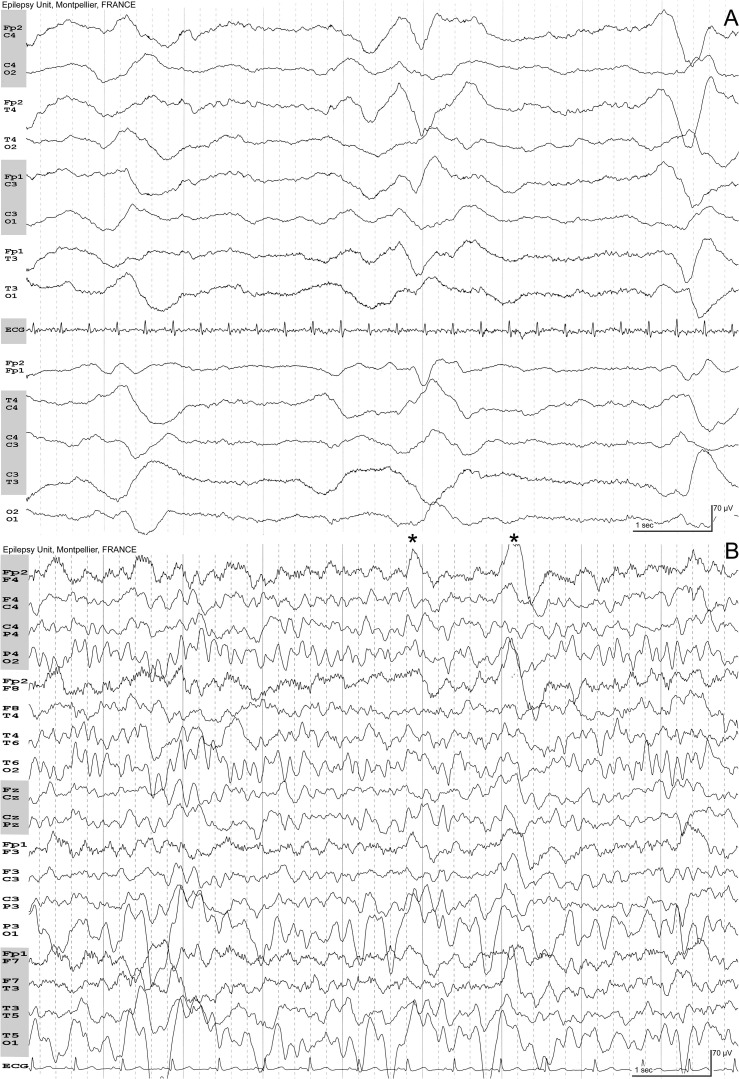

In the context of acute meningo-encephalitis, when periodic EEG bursts are seen bilaterally, and/or symmetrically, a non-HSV infection may be suspected (Fig. 4 ). Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is an inflammatory disorder, typically occurring a few days after a viral or bacterial infection, and is more common in children. The EEG may show bilateral slow-wave activity, more or less symmetrically (Dale et al., 2000, Höllinger et al., 2002, Kaplan and Rossetti, 2011), sometimes with focal slowing and less frequently, with epileptiform discharges (Dale et al., 2000, Höllinger et al., 2002). In children, anterior, bilateral, high-voltage and sometimes asymmetric complexes have been reported (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A, Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis: 17-year-old woman. Fever. Generalized tonic-clonic seizure followed by severe impairment of awareness requiring hospitalization in ICU. Numerous periodic diffuse complexes occurring every 3–4 seconds. B, Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis: 6-year-old boy. Status epilepticus five days after pneumonia. EEG, eight days after the status. Diagnosis of mycoplasma pneumonia on PCR. MRI showed hyperintensities of the caudate and lentiform nuclei bilaterally, especially on the left hemisphere with normalization one month later. Eyes closed. On the left occipital region, the background is abnormal with irregular delta waves. These waves did not react on eyes opening. Frontal complexes evocative of encephalitis can be seen (*) with higher amplitude on the right side.

4. Conclusion

Not every neurologic problem stems from a primary brain injury. In elderly patients with pneumonia, confusion is common. An isolated alteration of vigilance with a progressive change in consciousness ranging from somnolence to coma evoke an encephalopathy and, in the context of COVID-19, hypercapnic/hypoxic encephalopathy. Recent studies show that 8% to 15% of patients with this infection report headache (Helms et al., 2020, Mao et al., 2019), and this symptom was added to the list of COVID-19 symptoms (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). However, headache is common with fever and with other flu-like symptoms. As mentioned above, headache as a consequence of hypercapnia was frequently reported (1/3 of the patients) in acute respiratory failure in chronic pulmonary patients, and acute symptomatic seizures may occur (Laxenaire-Aug et al., 1970).

Although much information may be gleaned from EEG, the value of this information in the diagnosis and management of the patient must be weighed against the COVID-19 risks of infection to the technologist. EEG findings in COVID-19 are in their early days and care should be given not to generalize or “typify” any such patterns to COVID-19. These recommendations may help the EEG technologist, EEGer and clinician in the use of EEG in this new, challenging time.

Author contributions

Dr. Gélisse - Acquisition of data - Analysis and interpretation - Writing- Reviewing and Editing- Study supervision.

Dr. Rossetti - Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - Reviewing and Editing.

Dr. Genton - Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - Reviewing and Editing.

Dr. Crespel - Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - Reviewing and Editing.

Dr. Kaplan - Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content- Reviewing and Editing.

All co-authors have been substantially involved in the study and preparation of the manuscript. No undisclosed persons have had a primary role in the study or manuscript preparation. All co-authors have approved the submitted version of the paper and accept responsibility for its content.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr. Gélisse, Dr. Rossetti, Dr. Genton and Dr. Crespel report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Dr. Kaplan has been on the board of the American Board of Clinical Neurophysiology, the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society, consulted for Ceribell and lectured on EEG.

References

- André-Obadia N., Zyss J., Gavaret M., Lefaucheur J.P., Azabou E., Boulogne S. Recommendations for the use of electroencephalography and evoked potentials in comatose patients. Neurophysiol Clin. 2018;48:143–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2018.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi E., Sechi G.M., Mare C., Canevari F., Brancaglione A., Primi R. Lombardia CARe Researchers. Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest during the Covid-19 Outbreak in Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer G., Trinka E., Kaplan P.W. EEG patterns in hypoxic encephalopathies (post-cardiac arrest syndrome): fluctuations, transitions, and reactions. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30:477–489. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3182a73e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovanni F., Romagnosi F., Barbella G., Di Rocco A., Rossetti A.O., Taccone F.S. Standardized EEG analysis to reduce the uncertainty of outcome prognostication after cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05921-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caricato A., Melchionda I., Antonelli M. Continuous Electroencephalography Monitoring in Adults in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care. 2018;22:75. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-1997-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html.

- Clerkin K.J., Fried J.A., Raikhelkar J., Sayer G., Griffin J.M., Masoumi A., Disease Coronavirus. (COVID-19) and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2019;2020 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale R.C., de Sousa C., Chong W.K., Cox T.C., Harding B., Neville B.G. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis in children. Brain. 2000;123:2407–2422. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desforges M., Le Coupanec A., Dubeau P., Bourgouin A., Lajoie L., Dubé M. Human coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses: underestimated opportunistic pathogens of the central nervous system? Viruses. 2019;12:pii::E14. doi: 10.3390/v12010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunand A.C., Jallon P. Pseudoperiodic and paroxysmal electroencephalographic activities. Neurophysiol Clin. 2002;32:2–37. doi: 10.1016/s0987-7053(01)00288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaches J., Foncin J.F., Risvegliato M. The diagnostic value of the E.E.G. in herpes encephalitis. Rev EEG Neurophysiol. 1978;8:426–435. doi: 10.1016/S0370-4475(78)80037-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaches J. Periodic activity in the EEG. Rev Electroencephalogr Neurophysiol Clin. 1971;1:9–33. doi: 10.1016/s0370-4475(71)80003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspard N., Hirsch L.J., LaRoche S.M., Hahn C.D., Critical Westover MB., Care E.E.G. Monitoring Research Consortium. Interrater agreement for Critical Care EEG Terminology. Epilepsia. 2014;55:1366–1373. doi: 10.1111/epi.12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gélisse P., Crespel A., Genton P.E.E.G. vol. 3. John Libbey Eurotext; Montrouge: 2019. Neurology and Critical Care. (Atlas of Electroencephalography). [Google Scholar]

- Guérin C., Reignier J., Richard J.C., Beuret P., Gacouin A., Boulain T. PROSEVA Study Group. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms J., Kremer S., Merdji H., Clere-Jehl R., Schenck M., Kummerlen C. Neurologic Features in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch L.J., LaRoche S.M., Gaspard N., Gerard E., Svoronos A., Herman S.T. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society's Standardized Critical Care EEG Terminology: 2012 version. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30:1–27. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3182784729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höllinger P., Sturzenegger M., Mathis J., Schroth G., Hess C.W. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in adults: a reappraisal of clinical, CSF, EEG, and MRI findings. J Neurol. 2002;249:320–329. doi: 10.1007/s004150200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopp J.L., Atallah C. Electrodes and Montages. In: LaRoche S.M., Haider H.A., editors. Handbook of ICU EEG monitoring. second edition. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 2018. pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan P.W., Gélisse P., Sutter R. An Electroencephalographic Voyage in search of Triphasic Waves (TWs) - the Sirens and Corsairs on the Encephalopathy/EEG horizon: a survey of TWs. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000725. [in press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan P.W., Rossetti A.O. EEG patterns and imaging correlations in encephalopathy: encephalopathy part II. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;28:233–251. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31821c33a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxenaire-Aug M.C., Laxenaire M., Collombier N., Weber M., Saunier C. EEG changes during acute respiratory failure in chronic pulmonary patients. Respiration. 1970;27:345–362. doi: 10.1159/000192692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechien J.R., Chiesa-Estomba C.M., De Siati D.R., Horoi M., Le Bon S.D., Rodriguez A. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A, Kacmarek RM. Prone ventilation for adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. In: Parsons PE, section editor and Finlay G, deputy editor: UpToDate®. Wolters Kluwers; Apr 21, 2020.

- Mao L., Jin H., Wang M., Hu Y., Chen S., He Q. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampal N., Maciel C.B., Hirsch L.J. Electroencephalography and Artifact in the Intensive Care Unit. In: Tatum W.O., editor. Atlas of Artifacts in Clinical Neurophysiology. Demos Medical; New York: 2018. pp. 60–93. [Google Scholar]

- Roche-Campo F., Aguirre-Bermeo H., Mancebo J. Prone positioning in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): when and how? Presse Med. 2011;40:e585–e594. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti A.O., Tovar Quiroga D.F., Juan E., Novy J., White R.D., Ben-Hamouda N. Electroencephalography Predicts Poor and Good Outcomes After Cardiac Arrest: A Two-Center Study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:e674–e682. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth C., Ferbert A., Deinsberger W., Kleffmann J., Kästner S., Godau J. Does prone positioning increase intracranial pressure? A retrospective analysis of patients with acute brain injury and acute respiratory failure. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21:186–191. doi: 10.1007/s12028-014-0004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruijter B.J., Tjepkema-Cloostermans M.C., Tromp S.C., van den Bergh W.M., Foudraine N.A., Kornips F.H.M. Early electroencephalography for outcome prediction of postanoxic coma: A prospective cohort study. Ann Neurol. 2019;86:203–214. doi: 10.1002/ana.25518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schetz M., De Jong A., Deane A.M., Druml W., Hemelaar P., Pelosi P. Obesity in the critically ill: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:757–769. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05594-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonnet A., Chetboun M., Poissy J., Raverdy V., Noulette J., Duhamel A. Lille Intensive Care COVID-19 and Obesity study group. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JM. Atlas of EEG patterns. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippicott Williams & Wilkins, 2015.

- Sutter R., Stevens R.D., Kaplan P.W. Significance of triphasic waves in patients with acute encephalopathy: a nine-year cohort study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;124:1952–1958. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum W.O., Dworetzky B.A., Freeman W.D., Schomer D.L. Artifact: recording EEG in special care units. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;28:264–277. doi: 10.1097/WNP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum WO. Adult Electroencephalography Artifact. In Tatum WO, editor. Atlas of Artifacts in Clinical Neurophysiology. New York Demos Medical; 2018, p. 111–82.

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (a). Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected: Interim guidance V 1.2. WHO Reference Number: WHO/2019-nCoV/clinical/2020.4.

- World Health Organization (b). COVID-19 v4. Operational Support & Logistics Disease Commodity Packages.

- Xydakis M.S., Dehgani-Mobaraki P., Holbrook E.H., Geisthoff U.W., Bauer C., Hautefort C. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;S1473–3099(20):30293. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30293-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X., Pu K., Chen Z., Guo Q. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J.Y., Gaspard N., Hirsch L.J., Alkawadri R. Respiratory artifact on EEG independent of the respirator. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2014;31:e16–e17. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]