Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continues to sweep the world, causing infection of millions and death of hundreds of thousands. The respiratory disease that it caused, COVID-19 (stands for coronavirus disease in 2019), has similar clinical symptoms with other two CoV diseases, severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome (SARS and MERS), of which causative viruses are SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively. These three CoVs resulting diseases also share many clinical symptoms with other respiratory diseases caused by influenza A viruses (IAVs). Since both CoVs and IAVs are general pathogens responsible for seasonal cold, in the next few months, during the changing of seasons, clinicians and public heath may have to distinguish COVID-19 pneumonia from other kinds of viral pneumonia. This is a discussion and comparison of the virus structures, transmission characteristics, clinical symptoms, diagnosis, pathological changes, treatment and prevention of the two kinds of viruses, CoVs and IAVs. It hopes to provide information for practitioners in the medical field during the epidemic season.

Keywords: Coronaviruses, Influenza A viruses, Transmission, Diagnosis, Therapy, Prevention

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, caused a pneumonia epidemic in Wuhan, Hubei province of China. It erupted in many other countries in the following months and eventually became a worldwide pandemic. The pneumonia was officially named COVID-19 by World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. So far, the pandemic is still accelerating. More than 4.3 million people were confirmed infected, 290,000 more people died globally [2], and the virus transmission is expected to last for more than one year [3]. At the same time, other types of coronaviruses and influenza viruses, which have been widespread in the world, may invade human society again during this winter or in other circumstances, circulating together with the SARS-CoV-2 and causing more serious respiratory diseases [4,5]. It is necessary to investigate whether the simultaneous prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses, such as IAVs, can promote the spreading of each other. In addition, because the clinical symptoms caused by CoVs and IAVs infection are very similar to each other [6], it will bring further challenges to clinicians in the timely diagnosis and treatment of patients. This article will summarize and compare the epidemic characteristics, clinical symptoms, treatment, and prevention measures for the diseases which are caused by CoVs or IAVs respectively, hoping to provide a brief comparative information for the clinicians and researchers who are working in the related fields.

1. Viruses

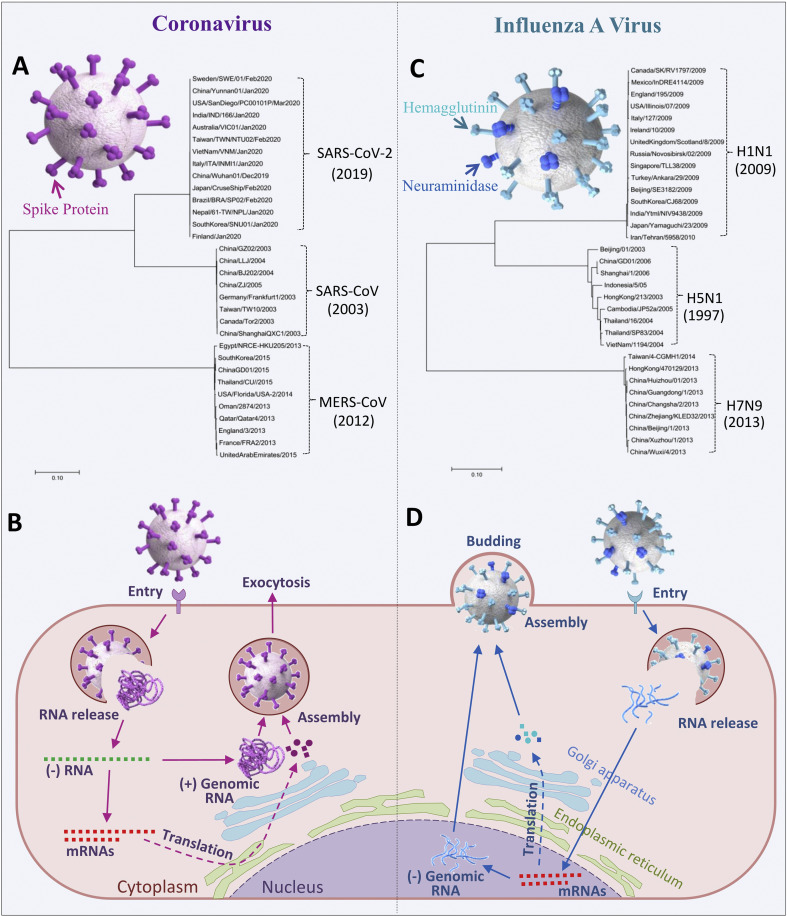

CoVs are enveloped, single strand positive-sense RNA viruses with a genome consisting of 26 to 32k nucleotides, expressing 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1 to nsp16) and four structural proteins, such as spike (S protein), membrane, envelope, and nucleocapsid proteins [7]. As shown in Fig. 1 A, S protein is located on the surface of virus particles, which plays a key role in virus entry into host cells, and is also one of the major targets of antiviral drugs and neutralizing antibodies [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. CoVs are divided into four genera which belongs to Coronaviridae, alpha, beta, delta and gamma CoVs. So far, there are seven CoVs causing human diseases, including three highly pathogenic CoVs (HPCoVs) (SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV) and four normal human CoVs (abbreviated as HCoVs) (HCoV229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU1) [12]. HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 belong to the alpha genus, while the other 5 CoVs belong to the beta genus. The genes of S protein from the three HPCoVs form 3 clusters, as shown in the polygenetic tree in Fig. 1A. Compared with MERS-CoV, the S protein gene of SARS-CoV-2 is a little bit closer to SARS-CoV, as reported they are sharing about 50% identity [13].

Fig. 1.

Spike proteins and life cycles of CoV and IAV. 3D models of CoV with spike protein genes based polygenetic tree (A) and summary diagram of the CoV life cycle (B). (C) IAV with HA protein genes based polygenetic tree and (D) summary diagram of IAV life cycle. Both neighbor-joining trees are generated by using ClustalX 1.83 and MEGA7 with the full length of glycoprotein genes downloaded from GenBank. The year in the brackets indicates that the time of the virus was reported first.

CoVs replication only occurs in the cytoplasm. As show in Fig. 1B, virus binds to its receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and HCoV-NL63), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) (MERS-CoV), 9-O-Acetylated sialic acid (HCoV-OC43), or human aminopeptidase N (CD13) (HCoV-229E) [14], and entry into the cell by direct membrane fusion or endocytosis, in which the virus membrane fusing with cell membrane or endosome membrane and releasing viral RNA, then the virus positive-sense RNA was used as a template to synthesize negative-sense genomic RNA, this was template again to transcript mRNAs and also to replicate progeny positive-sense RNA. Viral proteins were translated by mRNAs through the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus system for packaging into mature viral particles with the progeny RNA in the cytoplasm. Then the virions was transported to cell membrane and released by exocytosis [7,15].

Similar to CoV, IAV is also an enveloped virus, with genome of a single strand but negative-sense RNA, which is divided into eight segments, encoding 12 proteins, including PB2, PB1, PB1–F2, PB1 N40, PA, NP, HA, NA, M1, M2, NS, and NEP/NE2, respectively [16]. As shown in Fig. 1C, haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) are distributed on the surface of virus particles, which are the basis for subtype classification of IAVs and also play important roles during the process of virus invasion and mature virus releasing [17,18]. Like S protein of CoVs, HA and NA are very important targets of antiviral drugs and vaccines [[19], [20], [21]]. In recent 30 years, three subtypes of IAVs, including H1N1pdm09 virus causing 2009 flu pandemic [22], and two highly pathogenic avian viruses, H5N1 and H7N9 viruses, had caused severe respiratory diseases and resulted in thousands of deaths or high mortality in humans [23,24]. The majority subtype of seasonal IAVs is H3N2 [25]. The polygenetic tree in Fig. 1C displays the three clusters of HA genes. They show a distinct difference from each other, with the HA gene of H5N1 virus generating more mutations during its transmission as reported [26].

Compared to CoV, there are two major differences in the life cycle of IAV. First, the IAV needs to replicate its genome in the nucleus. Secondly, the virions are released by assembly and budding from cellular membrane. As illustrated in Fig. 1D, IAV binds to receptor α-2,3-linked sialic acid (H7N9 and H5N1) or α2,6-linked sialic acid (H1N1 and H3N2) to form endosome and enters into cell, and the viral RNA was released into the cytoplasm by viral-endosome membrane fusion. Then the viral RNA is imported into the nucleus, and once there starts both virus RNA transcription and replication. After mRNAs and progeny negative-sense RNAs are exported to cytoplasm, the proteins are translated and trafficked to the cell membrane into packaged RNAs. The mature virus then buds from the cells [27].

2. Transmission

For the spread of viruses, there are no borders between countries as more and more interactions and cooperation were established worldwide. Since the CoVs and IAVs were identified as the major pathogens for respiratory diseases in last century, they have traveled to many corners of the world [28,29]. The transmission and infectivity related information of these viruses were summarized in Table 1 . There are two seasonal flu viruses included, HCoVs and H3N2 IAV (HCoVs represents four CoVs that cause seasonal cold, HCoV229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU1, for convenience in following discussion, they will be denoted as one CoV in this article.). They usually cause moderate clinical symptoms and spread globally [28,30]. The rest of six viruses either show high pathogenicity or are highly transmissible, which could cause much danger for human society. These viruses are called here as HPHTs, which stands for high pathogenicity or highly transmissible viruses. Of the HPHTs, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 is accelerated due to its ability to transmit through airborne droplets during the incubation period [31]. That it may also transmit between human and animals becomes another challenge in the control of the pandemic [31]. Another two viruses, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, reported in 2012 and 2003 respectively, caused mortalities of 35% and 9% in patients respectively. Their transmission mostly started after the patients started showing clinical symptoms [15,32]. Therefore, they could not travel in humans too long before being discovered and controlled. All ages of people were susceptible to these 3 CoVs, but senior people were more likely to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and develop more severe clinical symptoms, while mostly younger people were infected with SARS-CoV [33,34].

Table 1.

A summary of transmission of CoVs and IAVs.

| Viruses | First circulated | Transmitted by contact via |

Susceptible age | Infected people | Infected countries | Mortality | Intermediate host | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human to human | Human to animal | Airborne droplets | ||||||||

| Highly pathogenic or highly transmissible | ||||||||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 2019 | Yes | NAb | Yes | Most were senior | Above 2 million by May 30 of 2020 | Global | About 7% by May 12 of 2020 | NA | [31,33,44,45] |

| MERS-CoV | 2012 | Rarely | Yes | Yes | All ages | 2468 by November of 2019 | 27 | About 35% | Dromedary camel, bat | [15,32,34] |

| SARS-CoV | 2003 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Most were younger | 8447 | 32 | 9% | Palm civet, bat | [15,33,46] |

| H7N9 IAV | 2013 | Rarely | Yes | Yes | Most were senior | 1568 by December of 2019 | Mainly in china | 37% | Avian | [42,47] [48] |

| H1N1pdm09 | 2009 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Most were younger | Above 200 million | Global | 0.001%–0.007% | Swine | [36,49] [50] |

| H5N1 IAV | 1997 | Rarely | Yes | Yes | Most were younger | 861 (2003–2020) | 17 (2003–2020) | 53% | Avian | [41,49] [51] |

| Seasonal | ||||||||||

| HCoVsa | 1966 | Yes | Yes | Yes | All ages | up to 20% of cold cases | Global | NA | Bat, mice, cattle, palm civet | [14,28,[52], [53], [54]] |

| H3N2 IAV | 1968 | Yes | Yes | NA | Most were senior | NA | Global | NA | Swine | [29,30,49,54] |

HCoVs represents the four CoVs which caused common cold, HCoV229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU1.

NA, data unavailable.

Some subtypes of IAVs also resulted in pandemic and caused large number of death tolls. Besides the well documented Spanish flu in 1918, H1N1pdm09 virus spread to 214 countries one year after it appeared in USA in 2009 [35]. It was noticed that the virus caused more deaths in people who are younger than 65 [36]. Some scientists deduced that the senior people may carry the immune memories from those induced by 1918H1N1-like flu viruses in their early years, which cross protected them from the H1N1pdm09 virus attack [37]. However, the fact is that the 1918H1N1 virus also caused more deaths in younger people [38]. H7N9 and H5N1 viruses were limited in transmission due to the similar reason mentioned above with MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV. However, the mortality of H7N9 is as high as 37%, and H5N1 is 53% [39,40]. Nevertheless, the high pathogenicity and high mortality make them easier to be identified and controlled at the beginning of the break. Although H7N9 and H5N1 viruses transmitted in humans ineffectively, their geographic expansion and genetic recombination still suggested the potential of forming the next pandemic [41,42].

As listed in Table 1, people are easily infected with CoVs or IAVs through direct contact and airborne droplets [43]. Since most of these viruses are of animal origin or use animals as intermediate hosts [29,31], it is necessary to keep a safe distance between humans and wild animals, as well as maintaining ecological balance in the world to prevent the breaking of epidemics in future.

3. Clinical symptoms and diagnosis

The major clinical symptoms are summarized in Table 2 . With the overview of the 8 viruses, the average incubation periods of the three HPCoVs are about 5 days or more, which are a little longer than other viruses. At the early stage of disease onset, the cases with the infection of different viruses mostly developed the same clinical symptoms -- cough and fever. However other clinical symptoms were various, such as myalgia which was common in HPCoVs, H1N1pdm09, and H3N2 IAV infection. Dyspnea was present in HPHTs infection, but not common in seasonal virus infections. Diarrhea was usually observed in patients with MERS and SARS, but not common in the other virus infections.

Table 2.

Major clinical symptoms of the CoVs and IAVs.

| Viruses | Highly pathogenic or highly transmissible |

Seasonal |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | MERS-CoV | SARS-CoV | H7N9 IAV | H1N1pdm09 | H5N1 IAV | HCoVs | H3N2 IAV | |

| Incubation period (day) | Average 5.2 | Average 5.2 | Average 4.6 | Average 5 | 2 to 7 | 2 to 5 | 2 to 5 | NAf |

| Early stage of onset | ||||||||

| Sore throat | –c | ± | ± | – | + | ± | + | + |

| Cough | +d | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Fever | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Myalgia | + | + | + | ± | + | ± | ± | + |

| Dyspnea | + | + | + | + | + | + | ± | – |

| Nausea and/or vomiting | ±e | 20%–35% | 20% | About 13% | 25% | ± | – | ± |

| Diarrhea | ± | + | + | About 13% | 25% | ± | ± | ± |

| Later stage of onset | ||||||||

| Bilateral pneumonia | + | + | + | + | + | + | ± | NA |

| Ground glass pneumonia | + | + | + | + | ± | – | – | NA |

| Hepatic injury | ± | + | + | + | ± | + | – | NA |

| Kidney injury | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Heart failure | + | – | – | ± | ± | + | – | NA |

| ARDSa | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | NA |

| LDH increaseb | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | NA |

| Lymphocytopenia | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Critical patient ratio | 10.0–30.6% ICU | 50% ICU | 25% ICU | >70% | 25% | 63% | 3.17% | 0.40% |

| Onset to critical (day) | 10 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 3 to 5 | 2 | NA | NA |

| References | [[55], [56], [57], [58]] | [34,[59], [60], [61]] | [52,[62], [63], [64], [65]] | [[66], [67], [68], [69]] | [[70], [71], [72], [73], [74]] | [[75], [76], [77]] | [[78], [79], [80]] | [[81], [82], [83], [84]] |

ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome.

LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase.

“–”, uncommon or none.

“+”, common.

“±”, some cases.

NA, data unavailable.

At the late stage of disease onset, compared with the seasonal viruses, all of the HPHTs can result in similar severe clinical symptoms, such as bilateral pneumonia, kidney damage, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), lactate dehydrogenase, and lymphocytopenia. In addition, three HPCoVs and H7N9 IAV infection usually showed ground glass pneumonia. MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, H7N9 IAV, and H5N1 IAV caused more hepatic injury. SARS-CoV-2 and H5N1 IAV meanwhile caused more heart failure. The critical patient ratio of the HPHTs infection can be 10%–70% after 2–10 days of the disease development.

To detect the causative viruses, similar measures were applied for CoVs and IAVs. The specimen can be swabs, blood, or trachea extracts. Then the viral RNAs can be directly identified by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) based methods, and the virus specific antibodies can be detected with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or related serological methods. More detailed information has been summarized in the previous publication [13]. In order to deal with the simultaneous transmission of IAVs and CoVs, especially the new coronavirus, it is necessary to develop rapid and simple differential diagnosis technologies and methods for identification of IAVs and CoVs.

4. Pathological change

Both CoVs and IAVs can cause ARDS and lead to multiple organ failure and death. The published pathological data that were collected from autopsy, lung biopsies and chest computed tomography (CT) scan are summarized in Table 3 . For patients with HPHTs infection, the general manifestations of the lung pathological change were inflammatory exudation or acute diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), with hyaline membrane formation, fibrin mucoid exudation, interstitial and alveolar edema, inflammatory interstitial infiltration and vascular congestion, epithelial cell proliferation, and pulmonary consolidation. However, there is no fibrin exudate found in the lungs of MERS patients, which may be related to the different stage of the disease progression. Almost all of the virus infections caused bronchioles injury except COVID-19 and H7N9 IAV [85,86], presented as the aggregation of fibrin in the bronchial intracavitary, the loss of cilia, the exfoliation of bronchioles epithelium, etc. It was reported that HCoVs were found to be associated with bronchiolitis in immunocompromised people, the elderly and young children, but showed light disease in the lungs.

Table 3.

The pathological changes of the patients after infection.

| Viruses | Highly pathogenic or highly transmissible |

Seasonal |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | MERS-CoV | SARS-CoV | H7N9 IAV | H1N1pdm09 | H5N1 IAV | HCoVs | H3N2 IAV | |

| Diffuse alveolar damage | +a | + | + | + | + | + | –b | NAc |

| Hyaline membrane | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| The pulmonary interstitial edema and lymphocytic infiltration | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Fibromyxoid exudation | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Pulmonary consolidation | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | NA |

| Bronchiolitis | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + |

| References | [[87], [88], [89]] | [61,90] | [[91], [92], [93]] | [94,95] | [[96], [97], [98]] | [[99], [100], [101], [102]] | [[103], [104], [105], [106]] | [107] |

“+”, common.

“−”, uncommon or none.

NA, data not available.

5. Treatment

The RNA virus inhibitors were designed to target the different steps of virus replication cycle. Some of them inhibit virus entry or release, some interfere gene synthesis, and some inhibit virus protease, or some modulate innate immune response, like interferons etc. However, there are no specific drugs for treatment of CoVs infection. Most often used for treatment of SARS and MERS are ribavirin and lopinavir/ritonavir. Ribavirin is similar to guanosine and inosine and interfere viral RNA replication, which is more frequently used in combination with interferons to treat chronic hepatitis C infection [108]. Lopinavir and ritonavir are two protease inhibitors previously approved for HIV treatment, which usually used together and ritonavir as CYP3A4 inhibitor to enhance the activity of lopinavir [109].

The suitable medications for COVID-19 are still under search. So far, one of the most promising drugs is remdesivir (GS-5734), produced by Gilead Science, a nucleoside analog that mimics adenosine for previously treatment of the Ebola virus infection [110]. Health authorities in China have initiated clinical trials at multiple places in Hubei province to evaluate the safety and efficacy of remdesivir on patients. However, under the pandemic emergencies, the patients who recovered from critical situation usually took multiple medications rather than remdesivir, which made assessment of the data from clinical trials somewhat complicated [111]. Besides of China, Gilead Science started phase III trial. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in the US are conducting phase II trial. The French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) also evaluated the effect of remdesivir and other treatment on COVID-19 patients [112].

Another promising drug is chloroquine or its analog, hydroxychloroquine. It was reported that these two drugs may inhibit viral entry by affecting PH dependent endocytosis, and they may also affect viral glycosylation by inhibiting glycosyl-transferases [113]. They were approved to treat or prevent malaria, as well as rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus etc. Moreover, hydroxychloroquine showed fewer side effects than chloroquine [114]. Several clinical studies on hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine provided fairly satisfying results, better trial designing would be needed to further confirm the therapeutic effectiveness [115]. Besides of these medications, lopinavir/ritonavir, interferons, as well as the Chinese medicine formulate were also recommended by China for treatment of COVID-19 [116].

Currently, for clinical treatment of influenza infection, there are only three classes of FDA (Food and Drug Administration)-approved antiviral drugs available, including M2 ion channel inhibitors (amantadine and rimantadine), neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir, zanamivir, peramivir and laninamivir), and the most recently RNA polymerase inhibitors (balxavirmarboxil) [117].

Amantadine and rimantadine can prevent the virus from shelling in the cytoplasm, thus inhibiting the transmission of virus offspring [118]. Although developed for many years, it has been reported frequently that they are ineffective in clinical treatment due to drug resistance of almost all currently circulating IAVs [119]. Furthermore, they have a relatively large side effect on the human central nervous system, thus are no longer recommended by WHO as the first choice of anti-influenza drugs for the treatment or prophylaxis of influenza [118].

Until now, the neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) are still the most ideal reagents for clinical treatment [120]. NAIs can prevent the hydrolytic activity of neuraminidase when the mature virus leaves the cell after budding, therefore stopping the virus from infecting healthy cells [121]. However, with heavy use in clinic, widespread oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 H275Y mutants have been identified [122]. According to a study carried out between 2008 and 2012 by WHO, oseltamivir resistance was found to be 2.9% (16/656 patients) [123], raising the alert that whether we can deal with influenza viruses once they break through the last line of defense? It has been found that probenecid can prevent the renal secretion of the parent compound of oseltamivir and significantly increase the blood concentration of oseltamivir [124]. Therefore the combination of oseltamivir and probenecid may be an important treatment option for severe patients.

Balxavir marboxil, with a brand name of Xofloza, can target to viral polymerase acidic protein (PA), block its endonuclease function, leading to the inhibition of virus mRNA transcription and effectively prevent influenza A virus infection [[125], [126], [127]]. The antiviral spectrum of Xofloza includes seasonal influenza strains and influenza strains resistant to oseltamivir, significantly reducing the viral load compared with oseltamivir [128]. T-705 is a new type of RNA polymerase inhibitor which can inhibit a wide range of viruses by directly entering into the viral RNA chain or by binding directly to the viral RNA polymerase domain to block viral RNA chain replication and transcription [129,130]. It has been approved for listing in Japan [131,132].

With this in mind, it is quite urgent to develop novel anti-influenza drugs with higher antiviral potency and resistance barrier. Hemagglutinin glycoprotein, located on the surface of influenza virions [133], plays a critical role in virus attachment and membrane fusion. Accompanied with HA structure characteristics elucidated, HA inhibitors appear to be one of the most promising candidates [[134], [135], [136], [137]]. With high efficacy and broad antiviral activity, some inhibitors targeting HA such as DAS181 and arbidol are currently in clinical development stage or partly approved for influenza virus infection [[138], [139], [140]]. Considering the antigen drift and shift of IAVs, the conserved regions on HA, such as the HA1 receptor binding sites (RBS) and the HA2 stem domain, are more attractive for new drug design [[141], [142], [143]]. A number of broad-spectrum neutralizing antibodies targeting above the two domains have been identified. For example, CR9114 exerts a broader antiviral effect against both influenza A and B viruses in mice by binding to HA stem domain, which may be useful for the treatment of severe influenza disease [144].

6. Prevention

There are many types of vaccines that have been used or are under investigation for human viral disease, such as live attenuated virus vaccine, inactivated whole virus vaccine, subunit or recombinant vaccine, DNA plasmids based vaccine, and mRNA based vaccine. However, there are no available vaccines for prevention of CoV infection. More than 10 years of research on the development of vaccines against MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV indicated that S protein has the ability to induce neutralizing antibodies to stop virus infection [145,146], which shines light on SARS-CoV-2 vaccine study.

For development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, an intense global effort is currently underway [147]. So far several vaccines candidates have moved into clinical trials in China. One of them moved into phase II trail on April 12, which was produced by the Institute of Bioengineering, Academy of Military Medicine (NCT04341389) [148]. The research team led by Professor Chen took the modified replication defective adenovirus as the vector, carried the S gene of the new CoV, to stimulate immune memory of S protein in humans. Their phase I trial was finished on March 27. In total 108 volunteers have completed the centralized medical observation without showing side effects (NCT04313127). In addition, LV-SMENP-DC, a dendritic cells vaccine, transduced with a lentivirus vector expression of several minigenes of SARS-CoV-2 and immunomodulatory genes, was developed by Shenzhen Geno-Immune Medical Institute (SGIMI) in China and used for injection of people along with activated virus antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells (NCT04276896). SGIMI also developed a second one using artificial antigen presenting cells (aAPCs) modified with lentivirus vector carrying similar genes with LV-SMENP-DC (NCT04299724). Two inactivated vaccines were approved for clinical trial as well, developed by the China National Pharmaceutical Group (Sinopharm) and Sinovac Research and Development Co., Ltd (NCT04352608) [147,[149], [150], [151], [152]].

In addition to COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials in China, there are many SARS-CoV-2 vaccine clinical trials underway worldwide [153], such as a mRNA vaccine, mRNA-1273, produced by Moderna, Inc. in US (NCT04283461); a DNA vaccine, INO-4800 by Inovio, Inc. in US (NCT04336410); Bifidobacterium probiotic carrying S protein gene by Symvivo in Canada (NCT04334980); adenovirus vaccine vector carrying S protein in UK (NCT04324606), etc. Whereas SARS-CoV-2 only started emerging in the human population, S protein, a major direct receptor interaction protein, and other viral proteins may continue modifying themselves to better adapt to humans [154]. Gene modification will bring more challenges into vaccine designing and development, especially the mutation in S protein which has been picked up by most of the vaccines candidates mentioned above.

Since the first H1N1 IAV vaccine was generated for prevention of the Spanish flu in 1938 by Jonas Salk and Thomas Francis [155,156], influenza vaccines have been improved dramatically. There are many types vaccines approved in US with trade names such as FluLaval, Fluarix, Agriflu, and Flublok. A live attenuated vaccine with the name of FluMist was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in US in 2003, and which is delivered through nasal spray [157]. To decrease side effects, animal and insect cells were also approved to replace chicken embryos for growth of vaccine strain [158]. To provide protection from most seasonal virus attacks using one shot, multiple dominant viruses were included into one vaccine, such as those containing 3 or 4 different circulating strains and called trivalent or quadrivalent vaccines [158,159]. Before a universal vaccine was successfully developed, it is necessary to switch vaccines strains year by year as the prevalent influenza viruses mutate their genes or change their subtypes very frequently to escape from the immune recognition [24,29].

Up to now, available commercial vaccines against the IAVs those listed in this article are H1N1, H5N1 and H3N2 IAV vaccines, but not H7N9 flu vaccine. For example, a trivalent inactivated vaccine, TIV, produced by Seqirus Inc., usually has H1N1, H3N2 and B subtype viruses. FluMist, produced by Medimmune, Inc, is also used for H1N1 flu vaccine [158]. For H5N1 IAV, several inactivated vaccines are approved for human use, such as Audenz produced by Seqirus Inc [158], Prepandrix produced by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals S.A [160]. H3N2 virus is usually a seasonal flu subtype in the last 30 years, of which the vaccine has been recommended for injection according to flu surveillance [29].

7. Summary

Human CoVs and IAVs share many characteristics, especially in HPHTs. Most of them infect the respiratory tract through direct contact and airway droplets and cause similar clinical symptoms like fever, cough, and sore throat. In contrast, MERS-CoV, H7N9 and H5N1 viruses rarely transmit between humans. SARS-CoV, H1N1pdm09, and H5N1 viruses easily infect younger people. Severe patients usually infected with HPHTs develop bilateral pneumonia, ARDS, respiratory failure, and even death. CT and autopsy showed that the main pulmonary pathological manifestations were DAD, hyaline membrane formation, alveolar and interstitial edema, fibromyxoid exudation, etc. At present, there are no specific and effective drugs or vaccines for the treatment and prevention of CoVs. However, thanks to clinicians’ and scientists’ efforts worldwide, some promising progress has been made in the treatment of the diseases. Although there are some drugs and vaccines for the treatment and prevention of IAVs, it is still necessary to further research and develop more effective methods of treatment and prevention to better control the influenza epidemic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Chungen Pan was supported by a grant from the Panyu Innovation and Entrepreneurship Leading Team Project (2017-R02-4). Shuwen Liu was supported by Major scientific and technological projects of Guangdong Province (2019B020202002), Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (ZZ13-035-02) and Evidence based capacity building project of traditional Chinese Medicine (2019XZZX-LG04).

Contributor Information

Chunhua Pan, Email: chungenp@163.com.

Shuwen Liu, Email: liusw@smu.edu.cn.

Chungen Pan, Email: chhpan@163.com.

References

- 1.Pan X., Ojcius D.M., Gao T., Li Z., Pan C., Pan C. Lessons learned from the 2019-nCoV epidemic on prevention of future infectious diseases. Microbes Infect. 2020;22:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- 3.Mahase E. Covid-19: outbreak could last until spring 2021 and see 7.9 million hospitalised in the UK. BMJ. 2020;368:m1071. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khodamoradi Z., Moghadami M., Lotfi M. Co-infection of coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza A: a report from Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23:239–243. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu X., Cai Y., Huang X., Yu X., Zhao L., Wang F. Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus in patient with pneumonia, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26 doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding Q., Lu P., Fan Y., Xia Y., Liu M. The clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients coinfected with 2019 novel coronavirus and influenza virus in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25781. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maier H.J., Bickerton E., Britton P. Preface. Coronaviruses. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:v. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang S., Hillyer C., Du L. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Trends Immunol. 2020;41:355–359. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y., Zhu Q., Liu S., Zhou Y., Yang B., Li J. Identification of a critical neutralization determinant of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus: importance for designing SARS vaccines. Virology. 2005;334:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia S., Liu M., Wang C., Xu W., Lan Q., Feng S. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020;30:343–355. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu S., Xiao G., Chen Y., He Y., Niu J., Escalante C.R. Interaction between heptad repeat 1 and 2 regions in spike protein of SARS-associated coronavirus: implications for virus fusogenic mechanism and identification of fusion inhibitors. Lancet. 2004;363:938–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15788-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu B., Ge X., Wang L.F., Shi Z. Bat origin of human coronaviruses. Virol J. 2015;12:221. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0422-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu F., Du L., Ojcius D.M., Pan C., Jiang S. Measures for diagnosing and treating infections by a novel coronavirus responsible for a pneumonia outbreak originating in Wuhan, China. Microb Infect. 2020;22:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin Y., Wunderink R.G. MERS, SARS and other coronaviruses as causes of pneumonia. Respirology. 2018;23:130–137. doi: 10.1111/resp.13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song Z., Xu Y., Bao L., Zhang L., Yu P., Qu Y. From SARS to MERS, thrusting coronaviruses into the spotlight. Viruses. 2019:11. doi: 10.3390/v11010059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dadonaite B., Gilbertson B., Knight M.L., Trifkovic S., Rockman S., Laederach A. The structure of the influenza A virus genome. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1781–1789. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0513-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dou D., Revol R., Ostbye H., Wang H., Daniels R. Influenza A virus cell entry, replication, virion assembly and movement. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1581. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosik I., Yewdell J.W. Influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase: yin(-)Yang proteins coevolving to thwart immunity. Viruses. 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/v11040346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang N., Zheng B.J., Lu L., Zhou Y., Jiang S., Du L. Advancements in the development of subunit influenza vaccines. Microb Infect. 2015;17:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloren K.K.S., Kwon J.J., Choi W.S., Jeong J.H., Ahn S.J., Choi Y.K. In vitro and in vivo characterization of novel neuraminidase substitutions in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus identified using laninamivir-mediated in vitro selection. J Virol. 2019;93 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01825-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walz L., Kays S.K., Zimmer G., von Messling V. Neuraminidase-inhibiting antibody titers correlate with protection from heterologous influenza virus strains of the same neuraminidase subtype. J Virol. 2018;92 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01006-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi Z., Hu H., Wang Z., Wang G., Li Y., Zhao X. Antibodies against H1N1 influenza virus cross-react with alpha-cells of pancreatic islets. J Diabetes Investig. 2018;9:265–269. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J., Li P., Yu Y., Fu Y., Jiang H., Lu M. Pulmonary surfactant-biomimetic nanoparticles potentiate heterosubtypic influenza immunity. Science. 2020;367 doi: 10.1126/science.aau0810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan C., Cheung B., Tan S., Li C., Li L., Liu S. Genomic signature and mutation trend analysis of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza A virus. PloS One. 2010;5:e9549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon B., Pichon M., Valette M., Burfin G., Richard M., Lina B. Whole genome sequencing of A(H3N2) influenza viruses reveals variants associated with severity during the 2016(-)2017 season. Viruses. 2019:11. doi: 10.3390/v11020108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tharakaraman K., Raman R., Viswanathan K., Stebbins N.W., Jayaraman A., Krishnan A. Structural determinants for naturally evolving H5N1 hemagglutinin to switch its receptor specificity. Cell. 2013;153:1475–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samji T. Influenza A: understanding the viral life cycle. Yale J Biol Med. 2009;82:153–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaunt E.R., Hardie A., Claas E.C., Simmonds P., Templeton K.E. Epidemiology and clinical presentations of the four human coronaviruses 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43 detected over 3 years using a novel multiplex real-time PCR method. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2940–2947. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00636-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan C., Wang G., Liao M., Zhang G.H., Jiang S. High genetic and antigenic similarity between a swine H3N2 influenza A virus and a prior human influenza vaccine virus: a possible immune pressure-driven cross-species transmission. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen J.D., Ross T.M. H3N2 influenza viruses in humans: viral mechanisms, evolution, and evaluation. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14:1840–1847. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1462639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y., Ning Z., Chen Y., Guo M., Liu Y., Gali N.K. Aerodynamic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in two Wuhan hospitals. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2271-3. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baharoon S., Memish Z.A. MERS-CoV as an emerging respiratory illness: a review of prevention methods. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2019:101520. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2019.101520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han Q., Lin Q., Jin S., You L. Coronavirus 2019-nCoV: a brief perspective from the front line. J Infect. 2020;80:373–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chafekar A., Fielding B.C., MERS-CoV Understanding the latest human coronavirus threat. Viruses. 2018;10 doi: 10.3390/v10020093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jhaveri R. Echoes of 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic in the COVID pandemic. Clin Therapeut. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.04.003. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Girard M.P., Tam J.S., Assossou O.M., Kieny M.P. The 2009 A (H1N1) influenza virus pandemic: a review. Vaccine. 2010;28:4895–4902. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chuah C.X.P., Lim R.L., Chen M.I.C. Investigating the legacy of the 1918 influenza pandemic in age-related seroepidemiology and immune responses to subsequent influenza A(H1N1) viruses through a structural equation model. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:2530–2540. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saglanmak N., Andreasen V., Simonsen L., Molbak K., Miller M.A., Viboud C. Gradual changes in the age distribution of excess deaths in the years following the 1918 influenza pandemic in Copenhagen: using epidemiological evidence to detect antigenic drift. Vaccine. 2011;29(Suppl 2):B42–B48. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu X., Xiao L., Li L. Research progress on human infection with avian influenza H7N9. Front Med. 2020;14:8–20. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0739-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Y., Cao Y., Li Z., Bai T., Zhang H., Hu S.X. Cross-neutralizing anti-hemagglutinin antibodies isolated from patients infected with avian influenza A (H5N1) virus. Biomed Environ Sci. 2020;33:103–113. doi: 10.3967/bes2020.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imai M., Herfst S., Sorrell E.M., Schrauwen E.J., Linster M., De Graaf M. Transmission of influenza A/H5N1 viruses in mammals. Virus Res. 2013;178:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanner W.D., Toth D.J., Gundlapalli A.V. The pandemic potential of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus: a review. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:3359–3374. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Algahtani H., Subahi A., Shirah B. Neurological complications of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2016;2016:3502683. doi: 10.1155/2016/3502683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wan Y., Shang J., Graham R., Baric R.S., Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.L., Abiona O. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skowronski D.M., Astell C., Brunham R.C., Low D.E., Petric M., Roper R.L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a year in review. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.091103.134135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson C.I., Barclay W.S., Zambon M.C., Pickles R.J. Infection of human airway epithelium by human and avian strains of influenza a virus. J Virol. 2006;80:8060–8068. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00384-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.https://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/influenza_h7n9/RiskAssessment_H7N9_23Feb20115.pdf?ua=1

- 49.Krammer F., Smith G.J.D., Fouchier R.A.M., Peiris M., Kedzierska K., Doherty P.C. Influenza. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:3. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0002-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.https://www.who.int/csr/don/2010_08_06/en

- 51.https://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/H5N1_cumulative_table_archives/en/

- 52.Su S., Wong G., Shi W., Liu J., Lai A.C.K., Zhou J. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corman V.M., Muth D., Niemeyer D., Drosten C. Hosts and sources of endemic human coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 2018;100:163–188. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan Q.S., Zhong J.S., Zhou H., Zhou J.Y. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 245 cases of influenza A (H3N2) Zhonghua Jiehe He Huxi Zazhi. 2019;42:510–514. doi: 10.3760/cma..j.issn.1001-0939.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Cardona-Ospina J.A., Gutierrez-Ocampo E., Villamizar-Pena R., Holguin-Rivera Y., Escalera-Antezana J.P. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020:101623. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y. Early transmission dynamics in wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Senga M., Arabi Y.M., Fowler R.A. Clinical spectrum of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Memish Z.A., Perlman S., Van Kerkhove M.D., Zumla A. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2020;395:1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Al-Rabiah F.A., Al-Hajjar S., Al-Barrak A. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hui D.S.C., Zumla A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: historical, epidemiologic, and clinical features. Infect Dis Clin. 2019;33:869–889. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leung G.M., Hedley A.J., Ho L.M., Chau P., Wong I.O., Thach T.Q. The epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in the 2003 Hong Kong epidemic: an analysis of all 1755 patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:662–673. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-9-200411020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Booth C.M., Matukas L.M., Tomlinson G.A., Rachlis A.R., Rose D.B., Dwosh H.A. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:2801–2809. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peiris J.S., Chu C.M., Cheng V.C., Chan K.S., Hung I.F., Poon L.L. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361:1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu L., Wang Z., Chen Y., Ding W., Jia H., Chan J.F. Clinical, virological, and histopathological manifestations of fatal human infections by avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1449–1457. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu H., Cowling B.J., Feng L., Lau E.H., Liao Q., Tsang T.K. Human infection with avian influenza A H7N9 virus: an assessment of clinical severity. Lancet. 2013;382:138–145. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61207-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao H.N., Lu H.Z., Cao B., Du B., Shang H., Gan J.H. Clinical findings in 111 cases of influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2277–2285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen X., Yang Z., Lu Y., Xu Q., Wang Q., Chen L. Clinical features and factors associated with outcomes of patients infected with a Novel Influenza A (H7N9) virus: a preliminary study. PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Poeppl W., Hell M., Herkner H., Stoiser B., Fritsche G., Schurz-Bamieh N. Clinical aspects of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in Austria. Infection. 2011;39:341–352. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0121-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patel M., Dennis A., Flutter C., Khan Z. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:128–142. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khandaker G., Dierig A., Rashid H., King C., Heron L., Booy R. Systematic review of clinical and epidemiological features of the pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2011;5:148–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Agarwal P.P., Cinti S., Kazerooni E.A. Chest radiographic and CT findings in novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus (S-OIV) infection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1488–1493. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peiris J.S., Poon L.L., Guan Y. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A virus (S-OIV) H1N1 virus in humans. J Clin Virol. 2009;45:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liem N.T., Tung C.V., Hien N.D., Hien T.T., Chau N.Q., Long H.T. Clinical features of human influenza A (H5N1) infection in Vietnam: 2004-2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1639–1646. doi: 10.1086/599031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hui D.S. Review of clinical symptoms and spectrum in humans with influenza A/H5N1 infection. Respirology. 2008;13(Suppl 1):S10–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yu H., Gao Z., Feng Z., Shu Y., Xiang N., Zhou L. Clinical characteristics of 26 human cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in China. PloS One. 2008;3:e2985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang S.F., Tuo J.L., Huang X.B., Zhu X., Zhang D.M., Zhou K. Epidemiology characteristics of human coronaviruses in patients with respiratory infection symptoms and phylogenetic analysis of HCoV-OC43 during 2010-2015 in Guangzhou. PloS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cabeca T.K., Granato C., Bellei N. Epidemiological and clinical features of human coronavirus infections among different subsets of patients. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7:1040–1047. doi: 10.1111/irv.12101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pyrc K., Berkhout B., van der Hoek L. The novel human coronaviruses NL63 and HKU1. J Virol. 2007;81:3051–3057. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01466-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wie S.H., So B.H., Song J.Y., Cheong H.J., Seo Y.B., Choi S.H. A comparison of the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of adult patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza A or B during the 2011-2012 influenza season in Korea: a multi-center study. PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Irving S.A., Patel D.C., Kieke B.A., Donahue J.G., Vandermause M.F., Shay D.K. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes of medically attended influenza A and influenza B in a defined population over four seasons: 2004-2005 through 2007-2008. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rogo L.D., Rezaei F., Marashi S.M., Yekaninejad M.S., Naseri M., Ghavami N. Seasonal influenza A/H3N2 virus infection and IL-1Beta, IL-10, IL-17, and IL-28 polymorphisms in Iranian population. J Med Virol. 2016;88:2078–2084. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaji M., Watanabe A., Aizawa H. Differences in clinical features between influenza A H1N1, A H3N2, and B in adult patients. Respirology. 2003;8:231–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang Z., Xia Y., Lu Y., Yang J., Zhang L., Su H. Prediction of H7N9 epidemic in China. Chin Med J. 2014;127:254–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang S., Gu D., Ouyang X., Xie W. Proinflammatory effects of the hemagglutinin protein of the avian influenza A (H7N9) virus and microRNAmediated homeostasis response in THP1 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:6241–6246. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shi H., Han X., Jiang N., Cao Y., Alwalid O., Gu J. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:425–434. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barton L.M., Duval E.J., Stroberg E., Ghosh S., Mukhopadhyay S. COVID-19 autopsies, Oklahoma, USA. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153:725–733. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ng D.L., Al Hosani F., Keating M.K., Gerber S.I., Jones T.L., Metcalfe M.G. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural findings of a fatal case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the United Arab Emirates, April 2014. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nicholls J.M., Poon L.L., Lee K.C., Ng W.F., Lai S.T., Leung C.Y. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1773–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Franks T.J., Chong P.Y., Chui P., Galvin J.R., Lourens R.M., Reid A.H. Lung pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a study of 8 autopsy cases from Singapore. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:743–748. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(03)00367-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gu J., Gong E., Zhang B., Zheng J., Gao Z., Zhong Y. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202:415–424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Feng Y., Hu L., Lu S., Chen Q., Zheng Y., Zeng D. Molecular pathology analyses of two fatal human infections of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:57–63. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang Q., Zhang Z., Shi Y., Jiang Y. Emerging H7N9 influenza A (novel reassortant avian-origin) pneumonia: radiologic findings. Radiology. 2013;268:882–889. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bal A., Suri V., Mishra B., Bhalla A., Agarwal R., Abrol A. Pathology and virology findings in cases of fatal influenza A H1N1 virus infection in 2009-2010. Histopathology. 2012;60:326–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mauad T., Hajjar L.A., Callegari G.D., da Silva L.F., Schout D., Galas F.R. Lung pathology in fatal novel human influenza A (H1N1) infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:72–79. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1420OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bai L., Gu L., Cao B., Zhai X.L., Lu M., Lu Y. Clinical features of pneumonia caused by 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus in Beijing, China. Chest. 2011;139:1156–1164. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nakajima N., Van Tin N., Sato Y., Thach H.N., Katano H., Diep P.H. Pathological study of archival lung tissues from five fatal cases of avian H5N1 influenza in Vietnam. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:357–369. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Korteweg C., Gu J. Pathology, molecular biology, and pathogenesis of avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1155–1170. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Uiprasertkul M., Kitphati R., Puthavathana P., Kriwong R., Kongchanagul A., Ungchusak K. Apoptosis and pathogenesis of avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:708–712. doi: 10.3201/eid1305.060572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peiris J.S., Yu W.C., Leung C.W., Cheung C.Y., Ng W.F., Nicholls J.M. Re-emergence of fatal human influenza A subtype H5N1 disease. Lancet. 2004;363:617–619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15595-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Tsoi H.W., Huang Y., Poon R.W., Chu C.M. Clinical and molecular epidemiological features of coronavirus HKU1-associated community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1898–1907. doi: 10.1086/497151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vabret A., Mourez T., Gouarin S., Petitjean J., Freymuth F. An outbreak of coronavirus OC43 respiratory infection in Normandy, France. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:985–989. doi: 10.1086/374222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pene F., Merlat A., Vabret A., Rozenberg F., Buzyn A., Dreyfus F. Coronavirus 229E-related pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:929–932. doi: 10.1086/377612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ebihara T., Endo R., Ma X., Ishiguro N., Kikuta H. Detection of human coronavirus NL63 in young children with bronchiolitis. J Med Virol. 2005;75:463–465. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Guarner J., Falcon-Escobedo R. Comparison of the pathology caused by H1N1, H5N1, and H3N2 influenza viruses. Arch Med Res. 2009;40:655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hall C.B. Ribavirin. Infect Dis Newsl (N Y) 1985;4:73–75. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2316(85)80008-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dyall J., Gross R., Kindrachuk J., Johnson R.F., Olinger G.G., Jr., Hensley L.E. Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome: current therapeutic options and potential targets for novel therapies. Drugs. 2017;77:1935–1966. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0830-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ledford H. Hopes rise for coronavirus drug remdesivir. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01295-8. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cao Y.C., Deng Q.X., Dai S.X. Remdesivir for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 causing COVID-19: an evaluation of the evidence. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020:101647. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.19/remdesivir-clinical-trials hwgcpa-g-hc

- 113.Sinha N., Balayla G. Hydroxychloroquine and covid-19. Postgrad Med. 2020 doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137785. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pereira B.B. Challenges and cares to promote rational use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: a timely review. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2020;23:177–181. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2020.1752340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chowdhury M.S., Rathod J., Gernsheimer J. A rapid systematic review of clinical trials utilizing chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19. Acad Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1111/acem.14005. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chan K.W., Wong V.T., Tang S.C.W. COVID-19: an update on the epidemiological, clinical, preventive and therapeutic evidence and guidelines of integrative Chinese-western medicine for the management of 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Am J Chin Med. 2020:1–26. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X20500378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pizzorno A., Padey B., Terrier O., Rosa-Calatrava M. Drug repurposing approaches for the treatment of influenza viral infection: reviving old drugs to fight against a long-lived enemy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:531. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jia Q., Li D., Wang X., Yang S., Qian Y., Qiu J. Simultaneous determination of amantadine and rimantadine in feed by liquid chromatography-Qtrap mass spectrometry with information-dependent acquisition. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2018;410:5555–5565. doi: 10.1007/s00216-018-1022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tsuruoka Y., Nakajima T., Kanda M., Hayashi H., Matsushima Y., Yoshikawa S. Simultaneous determination of amantadine, rimantadine, and memantine in processed products, chicken tissues, and eggs by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2017;1044–1045:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tejada S., Campogiani L., Sole-Lleonart C., Rello J. Alternative regimens of neuraminidase inhibitors for therapy of hospitalized adults with influenza: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Adv Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01347-5. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Doll M.K., Winters N., Boikos C., Kraicer-Melamed H., Gore G., Quach C. Safety and effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza treatment, prophylaxis, and outbreak control: a systematic review of systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2990–3007. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Abed Y., Pizzorno A., Bouhy X., Rheaume C., Boivin G. Impact of potential permissive neuraminidase mutations on viral fitness of the H275Y oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus in vitro, in mice and in ferrets. J Virol. 2014;88:1652–1658. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02681-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jarhult J.D. Oseltamivir (Tamiflu((R))) in the environment, resistance development in influenza A viruses of dabbling ducks and the risk of transmission of an oseltamivir-resistant virus to humans - a review. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2012;2 doi: 10.3402/iee.v2i0.18385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hill G., Cihlar T., Oo C., Ho E.S., Prior K., Wiltshire H. The anti-influenza drug oseltamivir exhibits low potential to induce pharmacokinetic drug interactions via renal secretion-correlation of in vivo and in vitro studies. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:13–19. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kakuya F., Haga S., Okubo H., Fujiyasu H., Kinebuchi T. Effectiveness of baloxavir marboxil against influenza in children. Pediatr Int. 2019;61:616–618. doi: 10.1111/ped.13855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Locke S.C., Splawn L.M., Cho J.C. Baloxavir marboxil: a novel cap-dependent endonuclease (CEN) inhibitor for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza. Drugs Today. 2019;55:359–366. doi: 10.1358/dot.2019.55.6.2999889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Koszalka P., Tilmanis D., Roe M., Vijaykrishna D., Hurt A.C. Baloxavir marboxil susceptibility of influenza viruses from the Asia-Pacific, 2012-2018. Antivir Res. 2019;164:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ng K.E. Xofluza (baloxavir marboxil) for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza. P T. 2019;44:9–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Furuta Y., Komeno T., Nakamura T. Favipiravir (T-705), a broad spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2017;93:449–463. doi: 10.2183/pjab.93.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cai L., Sun Y., Song Y., Xu L., Bei Z., Zhang D. Viral polymerase inhibitors T-705 and T-1105 are potential inhibitors of Zika virus replication. Arch Virol. 2017;162:2847–2853. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3436-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Fang Q.Q., Huang W.J., Li X.Y., Cheng Y.H., Tan M.J., Liu J. Effectiveness of favipiravir (T-705) against wild-type and oseltamivir-resistant influenza B virus in mice. Virology. 2020;545:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Koshimichi H., Tsuda Y., Ishibashi T., Wajima T. Population pharmacokinetic and exposure-response analyses of baloxavir marboxil in adults and adolescents including patients with influenza. J Pharmaceut Sci. 2019;108:1896–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Shen X., Zhang X., Liu S. Novel hemagglutinin-based influenza virus inhibitors. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(Suppl 2):S149–S159. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.06.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ilyushina N.A., Komatsu T.E., Ince W.L., Donaldson E.F., Lee N., O’Rear J.J. Influenza A virus hemagglutinin mutations associated with use of neuraminidase inhibitors correlate with decreased inhibition by anti-influenza antibodies. Virol J. 2019;16:149. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1258-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Li F., Ma C., Wang J. Inhibitors targeting the influenza virus hemagglutinin. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:1361–1382. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150227153919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lin D., Luo Y., Yang G., Li F., Xie X., Chen D. Potent influenza A virus entry inhibitors targeting a conserved region of hemagglutinin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;144:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Shen X.T., Zhang X.X., Liu S.W. Novel hemagglutinin-based influenza virus inhibitors. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5:S149–S159. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.06.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Salvatore M., Satlin M.J., Jacobs S.E., Jenkins S.G., Schuetz A.N., Moss R.B. DAS181 for treatment of parainfluenza virus infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients at a single center. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:965–970. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Dhakal B., D’Souza A., Pasquini M., Saber W., Fenske T.S., Moss R.B. DAS181 treatment of severe parainfluenza virus 3 pneumonia in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients requiring mechanical ventilation. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:8503275. doi: 10.1155/2016/8503275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Colombo R.E., Fiorentino C., Dodd L.E., Hunsberger S., Haney C., Barrett K. A phase 1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of DAS181 (Fludase(R)) in adult subjects with well-controlled asthma. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:54. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1358-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lvov D.K., Bogdanova V.S., Kirillov I.M., Shchelkanov M.Y., Burtseva E.I., Bovin N.V. [Evolution of pandemic influenza virus A(H1N1)pdm09 in 2009-2016: dynamics of receptor specificity of the first hemagglutinin subunit (HA1).] Vopr Virusol. 2019;64:63–72. doi: 10.18821/0507-4088-2019-64-2-63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Cueno M.E., Imai K., Shimizu K., Ochiai K. Homology modeling study toward identifying structural properties in the HA2 B-loop that would influence the HA1 receptor-binding site. J Mol Graph Model. 2013;44:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.L’Vov D.K., Burtseva E.I., Prilipov A.G., Bogdanova V.S., Shchelkanov M., Bovin N.V. [A possible association of fatal pneumonia with mutations of pandemic influenza A/H1N1 sw1 virus in the receptor-binding site of the HA1 subunit] Vopr Virusol. 2010;55:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Sutton T.C., Lamirande E.W., Bock K.W., Moore I.N., Koudstaal W., Rehman M. In vitro neutralization is not predictive of prophylactic efficacy of broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies CR6261 and CR9114 against lethal H2 influenza virus challenge in mice. J Virol. 2017;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01603-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Cao Z., Liu L., Du L., Zhang C., Jiang S., Li T. Potent and persistent antibody responses against the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein in recovered patients. Virol J. 2010;7:299. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Wang N., Shang J., Jiang S., Du L. Subunit vaccines against emerging pathogenic human coronaviruses. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:298. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Chen W.H., Strych U., Hotez P.J., Bottazzi M.E. The SARS-CoV-2 vaccine pipeline: an overview. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s40475-020-00201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zhang J., Zeng H., Gu J., Li H., Zheng L., Zou Q. vol. 8. 2020. (Progress and prospects on vaccine development against SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines (basel)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wang F., Kream R.M., Stefano G.B. An evidence based perspective on mRNA-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development. Med Sci Mon Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2020;26:e924700. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Pawelec G., Weng N.P. Can an effective SARS-CoV-2 vaccine be developed for the older population? Immun Ageing. 2020;17:8. doi: 10.1186/s12979-020-00180-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Bhattacharya M., Sharma A.R., Patra P., Ghosh P., Sharma G., Patra B.C. Development of epitope-based peptide vaccine against novel coronavirus 2019 (SARS-COV-2): immunoinformatics approach. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25736. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Ahmed S.F., Quadeer A.A., McKay M.R. Preliminary identification of potential vaccine targets for the COVID-19 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on SARS-CoV immunological studies. Viruses. 2020;12(3) doi: 10.3390/v12030254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Tu Y.F., Chien C.S., Yarmishyn A.A., Lin Y.Y., Luo Y.H., Lin Y.T. A review of SARS-CoV-2 and the ongoing clinical trials. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7) doi: 10.3390/ijms21072657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Yin C. Genotyping coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: methods and implications. Genomics. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.04.016. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Francis M.E., McNeil M., Dawe N.J., Foley M.K., King M.L., Ross T.M. vol. 7. 2019. (Historical H1N1 influenza virus imprinting increases vaccine protection by influencing the activity and sustained production of antibodies elicited at vaccination in ferrets. Vaccines (basel)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Huang P., Yu S., Wu C., Liang L. Highly conserved antigenic epitope regions of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase genes between 2009 H1N1 and seasonal H1N1 influenza: vaccine considerations. J Transl Med. 2013;11:47. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Schaefer S., Simon M. FluMist: reconsidering the contraindications. Clin Pediatr. 2015;54:1021. doi: 10.1177/0009922815591893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.McDonald J., Moore D. FluMist vaccine: questions and answers - summary. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Grohskopf L.A., Sokolow L.Z., Broder K.R., Walter E.B., Bresee J.S., Fry A.M. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices - United States, 2017-18 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep) 2017;66:1–20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6602a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Carter N.J., Plosker G.L. Prepandemic influenza vaccine H5N1 (split virion, inactivated, adjuvanted) [Prepandrix]: a review of its use as an active immunization against influenza A subtype H5N1 virus. BioDrugs. 2008;22:279–292. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200822050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]