Abstract

Assessment of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is increasingly recognized as an integral part of the prognostic workflow in triple-negative (TNBC) and HER2-positive breast cancer, as well as many other solid tumors. This recognition has come about thanks to standardized visual reporting guidelines, which helped to reduce inter-reader variability. Now, there are ripe opportunities to employ computational methods that extract spatio-morphologic predictive features, enabling computer-aided diagnostics. We detail the benefits of computational TILs assessment, the readiness of TILs scoring for computational assessment, and outline considerations for overcoming key barriers to clinical translation in this arena. Specifically, we discuss: 1. ensuring computational workflows closely capture visual guidelines and standards; 2. challenges and thoughts standards for assessment of algorithms including training, preanalytical, analytical, and clinical validation; 3. perspectives on how to realize the potential of machine learning models and to overcome the perceptual and practical limits of visual scoring.

Subject terms: Prognostic markers, Tumour immunology, Breast cancer, Tumour biomarkers, Cancer imaging

Introduction

Very large adjuvant trials have illustrated how the current schemes fail to stratify patients with sufficient granularity to permit optimal selection for clinical trials, likely owing to application of an overly limited set of clinico-pathologic features1,2. Histologic evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is emerging as a promising biomarker in solid tumors and has reached level IB-evidence as a prognostic marker in triple-negative (TNBC) and HER2-positive breast cancer3–5. Recently, the St Gallen Breast Cancer Expert Committee endorsed routine assessment of TILs for TNBC patients6. In the absence of adequate standardization and training, visual TILs assessment (VTA) is subject to a marked degree of ambiguity and interobserver variability7–9. A series of published guidelines from this working group (also known as TIL Working group or TIL-WG) aimed to standardize VTA in solid tumors, to improve reproducibility and clinical adoption10–12. TIL-WG is an international coalition of pathologists, oncologists, statisticians, and data scientists that standardize the assessment of Immuno-Oncology Biomarkers to aid pathologists, clinicians, and researchers in their research and daily practice. The value of these guidelines was highlighted in two studies systematically examining VTA reproducibility7,13. Nevertheless, VTA continues to have inherent limitations that cannot be fully addressed through standardization and training, including: 1. visual assessment will always have some degree of inter-reader variability; 2. the time constraints of routine practice make comprehensive assessment of large tissue sections challenging7,13; 3. perceptual limitations may introduce bias in VTA, for example, the same TILs density is perceived to be higher if there is limited stroma.

Research in using machine learning (ML) algorithms to analyze histology has recently produced encouraging results, fueled by improvements in both hardware and methodology. Algorithms that learn patterns from labeled data, based on “deep learning” neural networks, have obtained promising results in many challenging problems. Their success has translated well to digital pathology, where they have demonstrated outstanding performance in tasks like mitosis detection, identification of metastases in lymph node sections, tissue segmentation, prognostication, and computational TILs assessment (CTA)14–17. ‘Traditional' computational analysis of histology focuses on complex image analysis routines, that typically require extraction of handcrafted features and that often do not generalize well across data sets18,19. Although studies utilizing deep learning-based methods suggest impressive diagnostic performance, and better generalization across data sets, these methods remain experimental. Table 1 shows a sample of published CTA algorithms and discusses their strengths and limitations, in complementarity with a previous literature review by the TIL-WG16,20–31.

Table 1.

Sample CTA algorithms from the published literature.

| Stain | Approach | Ref | Data set | Method | Ground truth | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H&E | Patch classification | 24 | Multiple sites | CNN | Labeled patches (yes/no TILs) | Strengths: large-scale study with investigation of spatial TIL maps. AV includes molecular correlates. |

| TCGA data set | Annotations are open-access | Limitations: does not distinguish sTIL and iTIL; does not classify individual TILs*. | ||||

| Other: we defined CTA TIL score as fraction of patches that contain TILs, and found this to be correlated with VTA (R = 0.659, p = 2e-35). | ||||||

| Semantic segmentation | 16 | Breast | FCN | Traced region boundaries (exhaustive) | Strengths: large sample size and regions; investigates inter-rater variability at different experience levels; delineation of tumor, stroma and necrosis regions. | |

| TCGA data set | Annotations are open-access | Limitations: only detects dense TIL infiltrates*; does not classify individual TILs*. | ||||

| Semantic segmentation + Object detection | 25 | Breast | Seeding + FCN | Traced region boundaries (exhaustive) | Strengths: mostly follows TIL-WG VTA guidelines. AV includes correlation with consensus VTA scores and inter-pathologist variability. | |

| Private data set | Labeled & segmented nuclei within labeled region | Limitations: heavy ground truth requirement*; underpowered CV; and limited manually annotated slides. | ||||

| Object detection | 26 | Breast | SVM using morphology features | Labeled nuclei | Strengths: robust analysis and exploration of molecular TIL correlates. | |

| METABRIC data set | Qualitative density scores | Limitations: individual labeled nuclei are limited; does not distinguish TILs in different histologic regions*. | ||||

| 27 | Breast | RG and MRF | Labeled patches (low-medium-high density) | Strengths: explainable model and modular pipeline. | ||

| Private data set | Limitations: does not distinguish sTIL and iTIL; does not classify individual TILs. Limited AV sample size. | |||||

| 28 | NSCLC | Watershed + SVM classifier | Labeled nuclei | Strengths: explainable model; robust CV; captures spatial TIL clustering. | ||

| Private data sets | Limitations: limited AV; does not distinguish sTIL and iTIL. | |||||

| Object detection + inferred TIL localization | 31 | Breast | SVM classifier using morphology features | Labeled nuclei | Strengths: infers TIL localization using spatial localization. Robust CV. Investigation of spatial TIL patterns. | |

| METABRIC + private data sets | Qualitative density scores | Limitations: individual labeled nuclei are limited. not clear if spatial clustering has 1:1 correspondence with regions. | ||||

| IHC | Object detection + manual regions | 29 | Colon | Complex pipeline (non-DL) | Overall density estimates | Strengths: CTA within manual regions, including invasive margin. |

| Private data set | Limitations: unpublished AV. | |||||

| Object detection | 30 | Multiple | Multiple DL pipelines | Labeled nuclei within FOV (exhaustive) | Strengths: large-scale, robust AV. Systematic benchmarking. | |

| Private data set | Limitations: no CV; does not distinguish TILs in different regions*. |

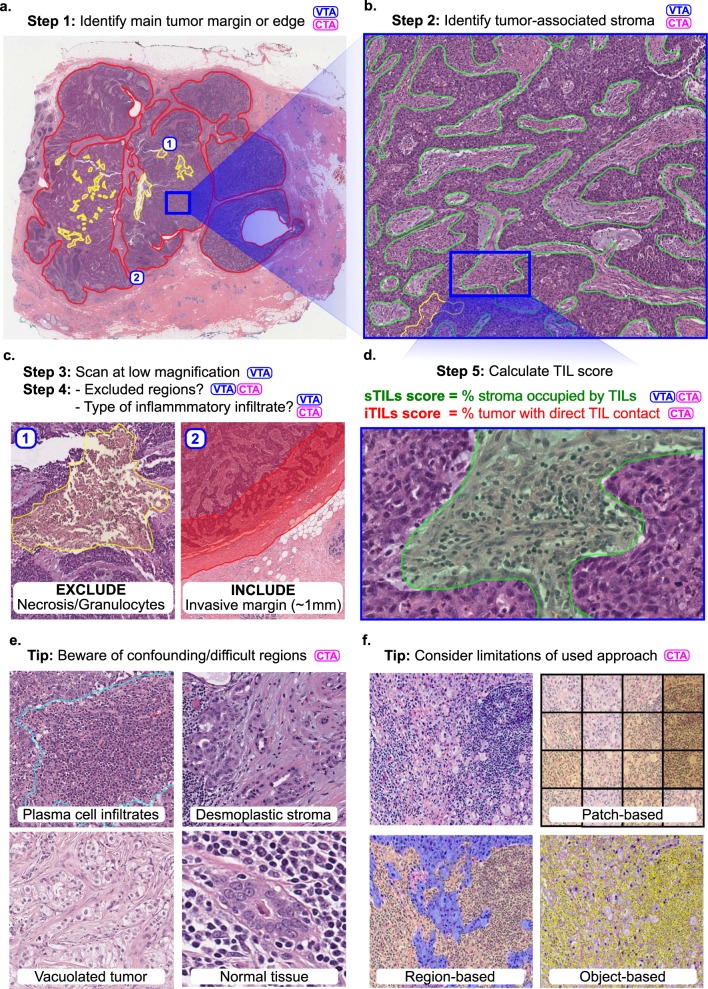

This non-exhaustive list has been restricted to H&E and chromogenic IHC, although excellent works exist showing CTA based on other approaches like multiplexed immunofluorescence21–23. Published CTA algorithms vary markedly in their approach to TIL scoring, the robustness of their validation, their interpretability, and their consistency with published VTA guidelines. Strengths and limitations of each publication is highlighted, with general limitations (related to the broad approach used, not the specific paper) are marked with an asterisk (*). Going forward, nuanced approaches are needed, ideally incorporating workflows for robust quantification and validation as presented in this paper. Different approaches have different ground truth requirements (illustrated in Fig. 1, panel f), hence the need for large-scale ground truth data sets. We encourage all future CTA publications to open-access their data sets whenever possible. Of note are two major efforts: 1. A group of scientists, including the US FDA and the TIL-WG, is collaborating to crowdsource pathologists and collect images and pathologist annotations that can be qualified by the FDA medical device development tool program; 2. The TIL-WG is organizing a challenge to validate CTA algorithms against clinical trial outcome data (CV).

AV analytical validation, CNN convolutional neural network, DL deep learning, FCN fully convolutional network, FOV field of view, MRF markov random field, RG region growing, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, SVM support vector machine.

This review and perspective provides a broad outline of key issues that impact the development and translation of computational tools for TILs assessment. The ideal intended outcome is that CTA is successfully integrated into the routine clinical workflow; there is significant potential for CTA to address inherent limitations in VTA, and partially to mitigate high clinical demands in remote and under-resourced settings. This is not too difficult to conceive, and there are documented success stories in the commercialization and clinical adoption of computational algorithms including pap smear cytology analyzers32, blood analyzers33, and automated immunohistochemistry (IHC) workflows for ER, PR, Her2, and Ki6734–38.

The impact of staining approach on algorithm design and deployment

The type of stain and imaging modality will have a significant impact on algorithm design, validation, and capabilities. VTA guideline from the TIL-WG focus on assessment of stromal TILs (sTIL) using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections, given their practicality and widespread availability, and the clear presentation of tissue architecture this stain provides10–12,39. Multiple studies have relied on in situ approaches like IHC, in situ hybridization (ISH), or genomic deconvolution in assessing TILs11,40,41. These modalities, however, are not typically used in daily clinical TILs assessment, as they are either still experimental, rely on assays of variable reliability, or involve stains not widely used in clinical practice, especially in low-income settings4,10,11. It is also difficult to quantitate and establish consistent thresholds for IHC measurement of even well-defined epitopes, such as Ki67 and ER, between different labs42,43. Moreover, there is no single IHC stain that highlights all mononuclear cells with high sensitivity and specificity, so H&E remains the stain typically used in the routine clinical setting44.

Despite these issues, there are significant potential advantages for using IHC with CTAs. By specifically staining TILs, IHC can make image analysis more reliable, and can also present new opportunities for granular TILs subclassification; different TIL subpopulations, including CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Tregs, NK cells, B cells, etc, convey pertinent information on immune activation and repression4,12. IHC is already utilized in standardization efforts for TILs assessment in colorectal carcinomas45,46. The specific highlighting of TILs by IHC can improve algorithm specificity47,48, and enable characterization of TIL subpopulations that have potentially distinct prognostic or predictive roles49,50. IHC can reduce misclassification of intratumoral TILs, which are difficult to reliably assess given their resemblance to tumor or supporting cells in many contexts like lobular breast carcinomas, small-blue-cell tumors like small cell lung cancer, and primary brain tumors4,12.

Characteristics of CTA algorithms that capture clinical guidelines

TIL-WG guidelines for VTA are somewhat complex4,10–12. There are VTA guidelines for many primary solid tumors and metastatic tumor deposits10,12, for untreated infiltrating breast carcinomas11, post-neoadjuvant residual carcinomas of the breast39, and for carcinoma in situ of the breast39. TILs score is defined as the fraction of a tissue compartment that is occupied by TILs (lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates). Different compartments have different prognostic relevance; tumor-associated sTILs is the most relevant in most solid tumors, whereas intratumoral TIL score (iTILs) has been reported to be prognostic, most notably in melanoma10. The spatial and visual context of TILs is strongly confounded by organ site, histologic subtype, and histomorphologic variables; therefore, it is important to provide situational context and instructions for clinical use of the CTA algorithms24,51,52. For example, a CTA algorithm designed for general-purpose breast cancer TILs scoring should be validated on different subtypes (infiltrating ductal, infiltrating lobular, mucinous, etc) and on a wide array of slides that capture variabilities in tumor phenotype (e.g., vacuolated tumor, necrotic tumor, etc), stromal phenotype (e.g., desmoplastic stroma), TIL densities, and sources of variability like staining and artifacts. That being said, it is plausible to assume that the biology and significance of TILs may vary in different clinical and genomic subtypes of the same primary cancer site, and that a general-purpose TILs-scoring algorithm may not be applicable. Further research into the commonalities and differences in the prognostic and biological value of TILs in different tissue sites and within different subtypes of the same cancer is warranted.

Clear inclusion criteria are helpful in deciding whether a slide is suitable for a particular CTA algorithm. For robust implementation, it is useful to: 1. detect when slides fail to meet its minimum quality; 2. provide some measure of confidence in its predictions; 3. be free of single points of failure (i.e., modular enough to tolerate failure of some sub-components); 4. be somewhat explainable, such that an expert pathologist can understand its limitations, common failure modes, and what the model seems to rely on in making decisions. Algorithms for measuring image quality and detecting artifacts will play an important role in the clinical implementation of CTA53.

From a computer vision perspective, we can subdivide CTA in two separate tasks: 1. segmentation of the region of interest (e.g., intratumoral stroma in case of sTIL assessment) and 2. detection of individual TILs within that region. In practice, a set of complementary computer vision problems often need to be addressed to score TILs (Fig. 1). To segment the region in which TILs will be assessed, it is also often needed to explicitly segment regions for exclusion from the analysis. Although these can be manually annotated by pathologists, these judgements are a significant source of variability in VTA, and developing algorithms capable of performing these tasks could improve reproducibility and standardization7–9.

Fig. 1. Outline of the visual (VTA) and computational (CTA) procedure for scoring TILs in breast carcinomas.

TIL scoring is a complex procedure, and breast carcinomas are used as an example. Specific guidelines for scoring different tumors are provided in the references. Steps involved in VTA and/or CTA are tagged with these abbreviations. CTA according to TIL-WG guidelines involves TIL scoring in different tissue compartments. a Invasive edge is determined (red) and key confounding regions like necrosis (yellow) are delineated. b Within the central tumor, tumor-associated stroma is determined (green). Other considerations and steps are involved depending on histologic subtype, slide quality, and clinical context. c Determination of regions for inclusion or exclusion in the analysis in accordance with published guidelines. d Final score is estimated (visually) or calculated (computationally). In breast carcinomas, stromal TIL score (sTIL) is used clinically. Intratumoral TIL score (iTIL) is subject to more VTA variability, which has hampered the generation of evidence demonstrating prognostic value; perhaps CTA of iTILs will prove less variable and, consequently, prognostic. e The necessity of diverse pathologist annotations for robust analytical validation of computational models. Desmoplastic stroma may be misclassified as tumor regions; Vacuolated tumor may be misclassified as stroma; intermixed normal acini or ducts, DCIS/LCIS, and blood vessels may be misclassified as tumor; plasma cells are sometimes misclassified as carcinoma cells. Note that while the term “TILs” includes lymphocytes, plasma cells and other small mononuclear infiltrates, lumping these categories may not be optimal from an algorithm design perspective; plasma cells tend to be morphologically different from lymphocytes in nuclear texture, size, and visible cytoplasm. f Various computational approaches may be used for computational scoring. The more granular the algorithm is, the more accurate/useful it is likely to be, but—as a trade-off—the more it relies on exhaustive manual annotations from pathologists. The least granular approach is patch classification, followed by region delineation (segmentation), then object detection (individual TILs). A robust computational scoring algorithm likely utilizes a combination of these (and related) approaches.

Specifically, segmentation of the “central tumor” and the “invasive margin/edge” enable TILs quantitation to be focused in relevant areas, excluding “distant” stroma along with normal tissue and surrounding structures. A semi-precise segmentation of invasive margin also allows sTILs score to be broken down for the margin and central tumor regions (especially, in colorectal carcinomas) and to characterize peri-tumoral TILs independently10. Within the central tumor, segmenting carcinoma cell nests and intratumoral stroma enables separate measurements for sTIL and iTIL densities. Furthermore, segmentation helps exclude key confounder regions that need to be excluded from the analysis. This includes necrosis, tertiary lymphoid structures, intermixed normal tissue or DCIS/LCIS (in breast carcinoma), pre-existing lymphoid stroma (in lymph nodes and oropharyngeal tumors), perivascular regions, intra-alveolar regions (in lung), artifacts, etc. This step requires high-quality segmentation annotations, and may prove to be challenging. Indeed, for routine clinical practice, it may be necessary to have a pathologist perform a quick visual confirmation of algorithmic region segmentations, and/or create high-level region annotations that may be difficult to produce algorithmically.

When designing a TIL classifier, consideration of key confounding cells is important. Although lymphocytes are, compared with tumor cells, relatively monomorphic, their small sizes offer little lymphocyte-specific texture information; small or perpendicularly cut stromal cells and even prominent nucleoli may result in misclassifications. Apoptotic bodies, necrotic debris, neutrophils, and some tumor cells (especially in lobular breast carcinomas and small-blue-round cell tumors) are other common confounders. Quantitation of systematic misclassification errors is warranted; some misclassifications will have contradictory consequences for clinical decision making. For example, neutrophils are evidently associated with adverse clinical outcomes, whereas TILs are typically associated with favorable outcomes51. Note that some of the TIL-WG clinical guidelines have been optimized for human scoring and are not very applicable in CTA algorithm design. For example, in breast carcinomas it is advised to “include but not focus on” tumor invasive edge TILs and TILs “hotspots”; CTA circumvents the need to address these cognitive biases11. To fully adhere to clinical guidelines, segmentation of TILs is warranted, so that the fraction of intratumoral stroma occupied by TILs is calculated.

Computer-aided versus fully automated TILs assessment

The extent to which computational tools can be used to complement clinical decision making is highly context-dependent, and is strongly impacted by cancer type and clinical setting54–57. In a computer-aided diagnosis paradigm, CTA is only used to provide guidance and increase efficiency in the workflow by any combination of the following: 1. calculating overall TILs score estimates to provide a frame-of-reference for the visual estimate; 2. directing the pathologist attention to regions of interest for TIL scoring, helping mitigate inconsistencies caused by heterogeneity in TILs density in different regions within the same slide; 3. providing a quantitative estimate for TILs density within regions of interest that the pathologist identifies, hence reducing ambiguity in visual estimation. Two models exist to assess this type of workflow during model development. In the traditional open assessment framework, the algorithm is trained on a set of manually annotated data points and evaluated on an independent held-out testing set. Alternatively, a closed-loop framework may be adopted, whereby pathologists can use the algorithmic output to re-evaluate their original decisions on the held-out set after exposure to the algorithmic results55,56. Both frameworks have pros and cons, although the closed-loop framework enables assessment of the potential impact that CTA has on altering the clinical decision-making process56.

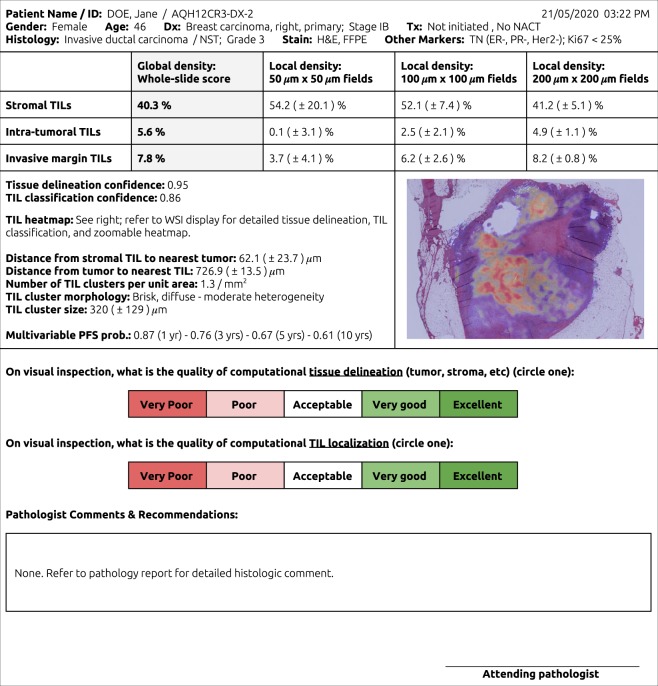

The alternative paradigm is an entirely computational pipeline for CTA. This approach clearly provides efficiency gains, which could markedly reduce costs and accelerate development in a research setting. When the sample sizes are large enough, a few failures (i.e., “noise”) could be tolerated without altering the overall conclusions. This is contrary to clinical medicine, where CTA is expected to be highly dependable for each patient, especially when it is used to guide treatment decisions. Owing to the highly consequential nature of medical decision-making, a stand-alone CTA algorithm requires a higher bar for validation. It is also likely that even validated stand-alone CTA tools will need “sanity checks” by pathologists, guarding against unexpected failures. For example, a CTA report may be linked to a WSI display system to visualize the intermediate results (i.e., detected tissue boundaries and TILs locations) that were used by the algorithm to reach its decision (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Conceptual pathology report for computational TIL assessment (CTA).

CTA reports might include global TIL estimates, broken down by key histologic regions, and estimates of classifier confidence. CTA reports are inseparably linked to WSI viewing systems, where algorithmic segmentations and localizations supporting the calculated scores are displayed for sanity check verification by the attending pathologist. Other elements, like local TIL estimates, TIL clustering results, and survival predictions may also be included.

We do not envision computational models at their current level of performance replacing pathologist expertize. In fact, we would argue that quite the opposite is true; CTA enables objective quantitative assessment of an otherwise ambiguous metric, enabling the pathologist to focus more of his/her time on higher-order decision-making tasks54. With that in mind, we argue that the efficiency gains from CTA in under-resourced settings are likely to be derived from workflow efficiency, as opposed to reducing the domain expertize required to make diagnostic and therapeutic assessments. When used in a telepathology setting, i.e., off-site review of WSIs, CTA is still likely to require supervision by an experienced attending pathologist. Naturally, this depends on infrastructure, and one may argue that the cost-effectiveness of CTA is determined by the balance between infrastructure costs (WSI scanners, computing facilities, software, cloud support, etc) and expected long-term efficiency gains.

Validation and training issues surrounding computational TIL scoring

CTA algorithms will need to be validated just like any prognostic or predictive biomarker to demonstrate preanalytical validation (Pre-AV), analytical validation (AV), clinical validation (CV), and clinical utility8,58,59. In brief, Pre-AV is concerned with procedures that occur before CTA algorithms are applied, and include items like specimen preparation, slide quality, WSI scanner magnification and specifications, image format, etc; AV refers to accuracy and reproducibility; CV refers to stratification of patients into clinically meaningful subgroups; clinical utility refers to overall benefit in the clinical setting, considering existing methods and practices. Other considerations include cost-effectiveness, implementation feasibility, and ethical implications59. VTA has been subject to extensive AV, CV, and clinical utility assessment, and it is critical that CTA algorithms are validated using the same high standards7,8. The use-case of a CTA algorithm, specifically whether it is used for computer-aided assessment or for largely unsupervised assessment, is a key determinant of the extent of required validation. Key resources to consult include: 1. Recommendations by the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer, for validation of diagnostic biomarkers; 2. Guidance documents by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); 3. Guidelines from the College of American Pathologists, for validation of diagnostic WSI systems60–64. Granted, some of these require modifications in the CTA context, and we will highlight some of these differences here.

Pre-AV is of paramount importance, as CTA algorithm performance may vary in the presence of artifacts, variability in staining, tissue thickness, cutting angle, imaging, and storage65–68. Trained pathologists, on the other hand, are more agile in adapting to variations in tissue processing, although these factors can still impact their visual assessment. Some studies have shown that the implementation of a DICOM standard for pathology images can improve standardization and improve interoperability if adopted by manufacturers67,69. Techniques for making algorithms robust to variations, rather than eliminating the variations, have also been widely studied and are commonly employed69–72. According to CAP guidelines, it is necessary to perform in-house validation of CTAs in all pathology laboratories, to validate the entire workflow (i.e., for each combination of tissue, stain, scanner, and CTA) using adequate sample size representing the entire diagnostic spectrum, and to re-validate whenever a significant component of the pre-analytic workflow changes62. Pre-AV and AV are most suitable in the in-house validation setting, as they can be performed with relatively fewer slides. It may be argued that proper in-house Pre-AV and AV suffice, provided large-scale prospective (or retrospective-prospective) AV, CV, and Clinical Utility studies were performed in a multi-center setting. Demonstrating local equivalency of Pre-AV and AV results can thus allow “linkage” to existing CV and Clinical Utility results assuming comparable patient populations.

AV typically involves quantitative assessment of CTA algorithm performance using ML metrics like segmentation or classification accuracy, prediction vs truth error, and area under receiver–operator characteristic curve or precision-recall curves. AV also includes validation against “non-classical” forms of ground truth like co-registered IHC, in which case the registration process itself may also require validation. AV is a necessary prerequisite to CV as it answers the more fundamental question: “Do CTA algorithms detect TILs correctly?”. AV should measure performance over the spectrum of variability induced by pre-analytic factors, and in cohorts that reflect the full range of intrinsic/biological variability. Naturally, this means that uncommon or rare subtypes of patterns are harder to validate owing to sample size limitations. AV of nucleus detection and classification algorithms has often neglected these issues, focusing on a large number of cells from a small number of cases.

Demonstrating the validity and generalization of prediction models is a complex process. Typically, the initial focus is on “internal” validation, using techniques like split-sample cross validation and bootstrapping. Later, the focus shifts to “external” validation, i.e., on an independent cohort from another institution. A hybrid technique called “internal–external” (cross-) validation may be appropriate when multi-institutional data sets (like the TCGA and METABRIC) are available, where training is performed on some hospitals/institutions and validation is performed on others. This was recommended by Steyerberg and Harrell and used in some computational pathology studies16,73–75.

Many of the events associated with cancer progression and subtyping are strongly correlated, so it may not be enough to show correspondence between global/slide-level CTA and VTA scores, as this shortcuts the AV process49. AV therefore relies on the presence of quality “ground truth” annotations. Unfortunately, there is a lack of open-access, large-scale, multi-institutional histology segmentation and/or TIL classification data sets, with few exceptions16,24,76,77. To help address this, a group of scientists, including the US FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) and the TIL-WG, is collaborating to crowdsource pathologists and collect images and pathologist annotations that can be qualified by the FDA/CDRH medical device development tool program (MDDT). The MDDT qualified data would be available to any algorithm developer to be used for the analytic evaluation of their algorithm performance in a submission to the FDA/CDRH78. The concept of “ground truth” in pathology can be vague and is often subjective, especially when dealing with H&E; it is therefore important to measure inter-rater variability by having multiple experts annotate the same regions and objects7,8. A key bottleneck in this process is the time commitment of pathologists, so collaborative, educational and/or crowdsourcing settings can help circumvent this limitation16,79. It should be stressed, however, that although annotations from non-pathologists or residents may be adequate for CTA algorithm training; validation may require ground truth annotations created or reviewed by experienced practicing pathologists16,80.

It is important to note that the ambiguity in ground truth (even if determined by consensus by multiple pathologists) typically warrants additional validation using objective criteria, most notably the ability to predict concrete clinical endpoints in validated data sets. One of the best ways to meet this validation bar is to use WSIs from large, multi-institutional randomized-controlled trials. To facilitate this effort, the TIL-WG is establishing strategic international partnerships to organize a machine learning challenge to validate CTA algorithms using clinical trials data. The training sets would be made available for investigators to train and fine tune their models, whereas separate blinded validation sets would only be provided once a locked-down algorithm has been established. Such resources are needed so that different algorithms and approaches can be directly compared on the same, high-quality data sets.

CTA for clinical versus academic use

Like VTA, CTA may be considered to fall under the umbrella of “imaging biomarkers,” and likely follows a similar validation roadmap to enable clinical translation and adoption38,81,82. CTA may be used in the following academic settings, to name a few: 1. as a surrogate marker of response to experimental therapy in animal models; 2. as a diagnostic or predictive biomarker in retrospective clinical studies using archival WSI data; 3. as a diagnostic or predictive biomarker in prospective randomized-controlled trials. Incorporation of imaging biomarkers into prospective clinical trials requires some form of analytical and clinical validation (using retrospective data, for example), resulting in the establishment of Standards of Practice for trial use81. Establishment of clinical validity and utility in multicentric prospective trials is typically a prerequisite for use in day-to-day clinical practice. In a research environment, it is not unusual for computational algorithms to be frequently tweaked in a closed-loop fashion. This tweaking can be as simple as altering hyper-parameters, but can include more drastic changes like modifications to the algorithm or (inter)active machine learning83,84. From a standard regulatory perspective, this is problematic as validation requires a defined “lockdown” and version control; any change generally requires at least partial re-validation64,85. It is therefore clear that the most pronounced difference between CTA use in basic/retrospective research, prospective trials, and routine clinical setting is the rigor of validation required38,81,82.

In a basic/retrospective research environment, there is naturally a higher degree of flexibility in adopting CTA algorithms. For example, all slides may be scanned using the same scanner and using similar tissue processing protocols. In this setting, there is no immediate need for worrying about algorithm generalization performance under external processing or scanning conditions. Likewise, it may not be necessary to validate the model using ground truth from multiple pathologists, especially if some degree of noise can be tolerated. Operational issues and practicality also play a smaller role in basic/retrospective research settings; algorithm speed and user friendliness of a particular CTA algorithm may not be relevant when routine/repetitive TILs assessment is not needed. Even the nature of CTA algorithms may be different in a non-clinical setting. For instance, even though there is conflicting evidence on the prognostic value of iTILs in breast cancer, there are motivations to quantify them in a research environment. It should be noted, however, that this flexibility is only applicable for CTA algorithms that are being used to support non-clinical research projects, not for those algorithms that are being validated for future clinical use.

The future of computational image-based immune biomarkers

CTA algorithms can enable characterization of the tumor microenvironment beyond the limits of human observers, and will be an important tool in identifying latent prognostic and predictive patterns of immune response. For one, CTA enables calculation of local TIL densities at various scales, which may serve as a guide to “pockets” of differential immune activation (Fig. 2). This surpasses what is possible with VTA and such measurements are easy to calculate provided that CTA algorithms detect TILs with adequate sensitivity and specificity. Several studies have identified genomic features that in hindsight are associated with TILs, and CTA presents opportunities for systematic investigation of these associations24,26,74,86,87. The emergence of assays and imaging platforms for multiplexed immunofluorescence and in situ hybridization will present new horizons for identifying predictive immunologic patterns and for understanding the molecular basis of tumor-immune interactions88,89; these approaches are increasingly becoming commoditized.

Previous work examined how various spatial metrics from cancer-associated stroma relate to clinical outcomes, and similar concepts can be borrowed; for example, metrics capturing the complex relationships between TILs and other cells/structures in the tumor microenvironment90. CTA may enable precise definitions of “intratumoral stroma”, for example using a quantitative threshold (i.e., “stroma within x microns from nearest tumor nest”). Similar concepts could be applied when differentiating tertiary lymphocytic aggregates, or other TIL hotspots, from infiltrating TILs that presumably have a direct role in anticancer response. It is also important to note that lymphocytic aggregation and other higher-order quantitative spatial metrics may play important prognostic roles yet to be discovered. A CTA study identified five broad categories of spatial organization of TILs infiltration, which are differentially associated with different cancer sites and subtypes24. Alternatively, TILs can be placed on a continuum, such that sTILs that have a closer proximity to carcinoma nests get a higher weight. iTILs could be characterized using similar reasoning. Depending on available ground truth, numerous spatial metrics can be calculated. Nuanced assessment of immune response can be performed; for example, number of apoptotic bodies and their relation to nearby immune infiltrates. It is likely that there would be a considerable degree of redundancy in the prognostic value of CTA metrics; such redundancy is not uncommon in genomic biomarkers91. This should not be problematic as long as statistical models properly account for correlated predictors. In fact, the ability to calculate numerous metrics for a very large volume of cases enables large-scale, systematic discovery of histological biomarkers, bringing us a step closer to evidence-based pathology practice.

Learning-based algorithms can be utilized to learn prognostic features directly from images in a minimally biased manner (without explicit detection of TILs), and to integrate these with standard clinico-pathologic and genomic predictors. The approach of using deep learning algorithms to first detect and classify TILs and structures in histology, and then to calculate quantitative features of these objects, presents a way of closely modeling the clinical guidelines set forth by expert pathologists. Here, the power of learning algorithms is directed at providing highly accurate and robust detection and classification to enable reproducible and quantitative measurement. Although this approach is interpretable and provides a clear path for analytic validation, the limitation is that quantitative features are prescribed instead of learned. Recently, there have been successful efforts to develop end-to-end prognostic deep learning models that learn to directly predict clinical outcomes from raw images without any intermediate classification of histologic objects like TILs17,92. Although these end-to-end learning approaches have the potential to learn latent prognostic patterns (including those impossible to assess visually), they are less interpretable and thus the factors driving the predictions are currently unknown.

Finally, we would note that one of the key limitations of machine learning models, and deep learning models in particular, is their opaqueness. It is often the case that model accuracy comes at a cost to explainability, giving rise to the term “black box” often associated with deep learning. The problem with less explainable models is that key features driving output may not be readily identifiable to evaluate biologic plausibility, and hence the only safeguard against major flaws is extensive validation93. Perhaps the most notorious consequence of this problem is “adversarial examples”, which are images that look natural to the human eye but that are specifically crafted (e.g., by malicious actors) to mislead deep learning models to make targeted misclassifications94. Nevertheless, recent advances in deep learning research have substantially increased model interpretability, and have devised key model training strategies (e.g., generative adversarial neural networks) to increase performance robustness93,95–97.

Conclusions

Advances in digital pathology and ML methodology have yielded expert-level performance in challenging diagnostic tasks. Evaluation of TILs in solid tumors is a highly suitable application for computational and computer-aided assessment, as it is both technically feasible and fills an unmet clinical need for objective and reproducible assessment. CTA algorithms need to account for the complexity involved in TIL-scoring procedures, and to closely follow guidelines for visual assessment where appropriate. TIL scoring needs to capture the concepts of stromal and intratumoral TILs and to account for confounding morphologies specific to different tumor sites, subtypes, and histologic patterns. Preanalytical factors related to imaging modality, staining procedure, and slide inclusion criteria are critical considerations, and robust analytical and clinical validation is key to adoption. In the clinical setting, CTA would ideally provide time- and cost-savings for pathologists, who face increasing demands for reporting biomarkers that are time-consuming to evaluate and subject to considerable inter- and intra- reader variability. In addition, CTA enables discovery of complex spatial patterns and genomic associations beyond the limits of visual scoring, and presents opportunities for precision medicine and scientific discovery.

Acknowledgements

L.A.D.C. is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants U01CA220401 and U24CA19436201. R.S. is supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF), grant No. 17-194. J.S. is supported in part by NCI grants UG3CA225021 and U24CA215109. A.M. is supported in part by NCI grants 1U24CA199374-01, R01CA202752-01A1, R01CA208236-01A1, R01 CA216579-01A1, R01 CA220581-01A1, 1U01 CA239055-01, National Center for Research Resources under award number 1 C06 RR12463-01, VA Merit Review Award IBX004121A from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service, the DOD Prostate Cancer Idea Development Award (W81XWH-15-1-0558), the DOD Lung Cancer Investigator-Initiated Translational Research Award (W81XWH-18-1-0440), the DOD Peer Reviewed Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-16-1-0329), the Ohio Third Frontier Technology Validation Fund, the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation Program in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and the Clinical and Translational Science Award Program (CTSA) at Case Western Reserve University. S.G. is supported by Susan G Komen Foundation (CCR CCR18547966) and a Young Investigator Grant from the Breast Cancer Alliance. T.O.N. receives funding support from the Canadian Cancer Society. M.M.S. is supported by P30 CA16672 DHHS/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG). A.S. is supported in part by NCI grants 1UG3CA225021, 1U24CA215109, and Leidos 14 × 138. This work includes contributions from, and was reviewed by, individuals at the F.D.A. This work has been approved for publication by the agency, but it does not necessarily reflect official agency policy. Certain commercial materials and equipment are identified in order to adequately specify experimental procedures. In no case does such identification imply recommendation or endorsement by the FDA, nor does it imply that the items identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, the United States Government, or other governments or entities. The following is a list of current members of the International Immuno-Oncology Working Group (TILs Working Group). Members contributed to the manuscript through discussions, including at the yearly TIL-WG meeting, and have reviewed and provided input on the manuscript. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in the work of the TILs Working Group and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of their employer.

Author contributions

This report is produced as a result of discussion and consensus by members of the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group (TILs Working Group). All authors have contributed to: 1) the conception or design of the work, 2) drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, 3) final approval of the completed version, 4) accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests

J.T. is funded by Visiopharm A/S, Denmark. A.M. is an equity holder in Elucid Bioimaging and in Inspirata Inc. He is also a scientific advisory consultant for Inspirata Inc. In addition he has served as a scientific advisory board member for Inspirata Inc, Astrazeneca, Bristol Meyers-Squibb and Merck. He also has sponsored research agreements with Philips and Inspirata Inc. His technology has been licensed to Elucid Bioimaging and Inspirata Inc. He is also involved in an NIH U24 grant with PathCore Inc, and three different R01 grants with Inspirata Inc. S.R.L. received travel and educational funding from Roche/Ventana. A.J.L. serves as a consultant for BMS, Merck, AZ/Medimmune, and Genentech. He is also provides consulting and advisory work for many other companies not relevant to this work. FPL does consulting for Astrazeneca, BMS, Roche, MSD Pfizer, Novartis, Sanofi, and Lilly. S.Ld.H., A.K., M.K., U.K., and M.B. are employees of Roche. J.M.S.B. is consultant for Insight Genetics, BioNTech AG, Biothernostics, Pfizer, RNA Diagnostics, and OncoXchange. He received funding from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Genoptix, Agendia, NanoString technologies, Stratifyer GmBH, and Biotheranostics. L.F.S.K. is a consultant for Roche and Novartis. J.K.K. and A.H.B. are employees of PathAI. D.L.R. is on the advisory board for Amgen, Astra Xeneca, Cell Signaling Technology, Cepheid, Daiichi Sankyo, GSK, Konica/Minolta, Merck, Nanostring, Perking Elmer, Roche/Ventana, and Ultivue. He has received research support from Astrazeneca, Cepheid, Navigate BioPharma, NextCure, Lilly, Ultivue, Roche/Ventana, Akoya/Perkin Elmer, and Nanostring. He also has financial conflicts of interest with BMS, Biocept, PixelGear, and Rarecyte. S.G. is a consultant for and/or receives funding from Eli Lilly, Novartis, and G1 Therapeutics. J.A.W.M.vdL. is a member of the scientific advisory boards of Philips, the Netherlands and ContextVision, Sweden, and receives research funding from Philips, the Netherlands and Sectra, Sweden. S.A. is a consultant for Merck, Genentech, and BMS, and receives funding from Merck, Genentech, BMS, Novartis, Celgene, and Amgen. T.O.N. has consulted for Nanostring, and has intellectual property rights and ownership interests from Bioclassifier LLC. S.L. receives research funding to her institution from Novartis, Bristol Meyers-Squibb, Merck, Roche-Genentech, Puma Biotechnology, Pfizer and Eli Lilly. She has acted as consultant (not compensated) to Seattle Genetics, Pfizer, Novartis, BMS, Merck, AstraZeneca and Roche-Genentech. She has acted as consultant (paid to her institution) to Aduro Biotech. J.H. is director and owner of Slide Score BV. M.M.S. is a medical advisory board member of OptraScan. R.S. has received research support from Merck, Roche, Puma; and travel/congress support from AstraZeneca, Roche and Merck; and he has served as an advisory board member of BMS and Roche and consults for BMS.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A full list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Roberto Salgado, Email: roberto@salgado.be.

Lee A. D. Cooper, Email: lee.cooper@northwestern.edu

International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group:

Aini Hyytiäinen, Akira I. Hida, Alastair Thompson, Alex Lefevre, Allen Gown, Amy Lo, Anna Sapino, Andre Moreira, Andrea Richardson, Andrea Vingiani, Andrew M. Bellizzi, Andrew Tutt, Angel Guerrero-Zotano, Anita Grigoriadis, Anna Ehinger, Anna C. Garrido-Castro, Anne Vincent-Salomon, Anne-Vibeke Laenkholm, Ashley Cimino-Mathews, Ashok Srinivasan, Balazs Acs, Baljit Singh, Benjamin Calhoun, Benjamin Haibe-Kans, Benjamin Solomon, Bibhusal Thapa, Brad H. Nelson, Carlos Castaneda, Carmen Ballesteroes-Merino, Carmen Criscitiello, Carolien Boeckx, Cecile Colpaert, Cecily Quinn, Chakra S. Chennubhotla, Charles Swanton, Cinzia Solinas, Crispin Hiley, Damien Drubay, Daniel Bethmann, Deborah A. Dillon, Denis Larsimont, Dhanusha Sabanathan, Dieter Peeters, Dimitrios Zardavas, Doris Höflmayer, Douglas B. Johnson, E. Aubrey Thompson, Edi Brogi, Edith Perez, Ehab A. ElGabry, Elizabeth F. Blackley, Emily Reisenbichler, Enrique Bellolio, Ewa Chmielik, Fabien Gaire, Fabrice Andre, Fang-I Lu, Farid Azmoudeh-Ardalan, Forbius Tina Gruosso, Franklin Peale, Fred R. Hirsch, Frederick Klaushen, Gabriela Acosta-Haab, Gelareh Farshid, Gert van den Eynden, Giuseppe Curigliano, Giuseppe Floris, Glenn Broeckx, Harmut Koeppen, Harry R. Haynes, Heather McArthur, Heikki Joensuu, Helena Olofsson, Ian Cree, Iris Nederlof, Isabel Frahm, Iva Brcic, Jack Chan, Jacqueline A. Hall, James Ziai, Jane Brock, Jelle Wesseling, Jennifer Giltnane, Jerome Lemonnier, Jiping Zha, Joana M. Ribeiro, Jodi M. Carter, Johannes Hainfellner, John Le Quesne, Jonathan W. Juco, Jorge Reis-Filho, Jose van den Berg, Joselyn Sanchez, Joseph Sparano, Joël Cucherousset, Juan Carlos Araya, Julien Adam, Justin M. Balko, Kai Saeger, Kalliopi Siziopikou, Karen Willard-Gallo, Karolina Sikorska, Karsten Weber, Keith E. Steele, Kenneth Emancipator, Khalid El Bairi, Kim R. M. Blenman, Kimberly H. Allison, Koen K. van de Vijver, Konstanty Korski, Lajos Pusztai, Laurence Buisseret, Leming Shi, Liu Shi-wei, Luciana Molinero, M. Valeria Estrada, Maartje van Seijen, Magali Lacroix-Triki, Maggie C. U. Cheang, Maise al Bakir, Marc van de Vijver, Maria Vittoria Dieci, Marlon C. Rebelatto, Martine Piccart, Matthew P. Goetz, Matthias Preusser, Melinda E. Sanders, Meredith M. Regan, Michael Christie, Michael Misialek, Michail Ignatiadis, Michiel de Maaker, Mieke van Bockstal, Miluska Castillo, Nadia Harbeck, Nadine Tung, Nele Laudus, Nicolas Sirtaine, Nicole Burchardi, Nils Ternes, Nina Radosevic-Robin, Oleg Gluz, Oliver Grimm, Paolo Nuciforo, Paul Jank, Petar Jelinic, Peter H. Watson, Prudence A. Francis, Prudence A. Russell, Robert H. Pierce, Robert Hills, Roberto Leon-Ferre, Roland de Wind, Ruohong Shui, Sabine Declercq, Sam Leung, Sami Tabbarah, Sandra C. Souza, Sandra O’Toole, Sandra Swain, Scooter Willis, Scott Ely, Seong- Rim Kim, Shahinaz Bedri, Sheeba Irshad, Shi-Wei Liu, Shona Hendry, Simonetta Bianchi, Sofia Bragança, Soonmyung Paik, Stephen B. Fox, Stephen J. Luen, Stephen Naber, Sua Luz, Susan Fineberg, Teresa Soler, Thomas Gevaert, Timothy d’Alfons, Tom John, Tomohagu Sugie, Veerle Bossuyt, Venkata Manem, Vincente Peg Cámaea, Weida Tong, Wentao Yang, William T. Tran, Yihong Wang, Yves Allory, and Zaheed Husain

References

- 1.Piccart-Gebhart M, et al. Adjuvant lapatinib and trastuzumab for early human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: results from the randomized phase III adjuvant lapatinib and/or Trastuzumab Treatment Optimization Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:1034–1042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Minckwitz G, et al. Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:122–131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denkert C, et al. Tumor-associated lymphocytes as an independent predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:105–113. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savas P, et al. Clinical relevance of host immunity in breast cancer: from TILs to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016;13:228–241. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011;128:305–310. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balic, M., Thomssen, C., Würstlein, R., Gnant, M. & Harbeck, N. St. Gallen/Vienna 2019: a brief summary of the consensus discussion on the optimal primary breast cancer treatment. Breast Care14, 103–110 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Denkert C, et al. Standardized evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer: results of the ring studies of the international immuno-oncology biomarker working group. Mod. Pathol. 2016;29:1155–1164. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wein L, et al. Clinical validity and utility of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in routine clinical practice for breast cancer patients: current and future directions. Front. Oncol. 2017;7:156. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brambilla E, et al. Prognostic effect of tumor lymphocytic infiltration in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:1223–1230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendry S, et al. Assessing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in solid tumors: a practical review for pathologists and proposal for a standardized method from the international immunooncology biomarkers working group: part 1: assessing the host immune response, tils in invasive breast carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ, metastatic tumor deposits and areas for further research. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2017;24:235–251. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salgado R, et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26:259–271. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendry S, et al. Assessing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in solid tumors: a practical review for pathologists and proposal for a standardized method from the international immuno-oncology biomarkers working group: part 2: tils in melanoma, gastrointestinal tract carcinomas, non-small cell lung carcinoma and mesothelioma, endometrial and ovarian carcinomas, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, genitourinary carcinomas, and primary brain tumors. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2017;24:311–335. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunyé TT, Mercan E, Weaver DL, Elmore JG. Accuracy is in the eyes of the pathologist: the visual interpretive process and diagnostic accuracy with digital whole slide images. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017;66:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehteshami Bejnordi B, et al. Diagnostic assessment of deep learning algorithms for detection of lymph node metastases in women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2017;318:2199–2210. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.14585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tellez, D. et al. Whole-slide mitosis detection in H&E breast histology using PHH3 as a reference to train distilled stain-invariant convolutional networks. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging (2018). 10.1109/TMI.2018.2820199 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Amgad M, et al. Structured crowdsourcing enables convolutional segmentation of histology images. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:3461–3467. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mobadersany P, et al. Predicting cancer outcomes from histology and genomics using convolutional networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E2970–E2979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717139115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litjens G, et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017;42:60–88. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janowczyk A, Madabhushi A. Deep learning for digital pathology image analysis: a comprehensive tutorial with selected use cases. J. Pathol. Inform. 2016;7:29. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.186902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klauschen F, et al. Scoring of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes: from visual estimation to machine learning. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018;52:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barua S, et al. Spatial interaction of tumor cells and regulatory T cells correlates with survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2018;117:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schalper, K. A. et al. Objective measurement and clinical significance of TILs in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 107, dju435 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Brown JR, et al. Multiplexed quantitative analysis of CD3, CD8, and CD20 predicts response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:5995–6005. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saltz J, et al. Spatial organization and molecular correlation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes using deep learning on pathology images. Cell Rep. 2018;23:181–193.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amgad, M. et al. Joint region and nucleus segmentation for characterization of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer. in Medical Imaging 2019: Digital Pathology (eds. Tomaszewski, J. E. & Ward, A. D.) 20 (SPIE, 2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Yuan Y, et al. Quantitative image analysis of cellular heterogeneity in breast tumors complements genomic profiling. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:157ra143. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basavanhally AN, et al. Computerized image-based detection and grading of lymphocytic infiltration in HER2+ breast cancer histopathology. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010;57:642–653. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2035305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corredor G, et al. Spatial architecture and arrangement of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for predicting likelihood of recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:1526–1534. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon HH, et al. Intertumoral heterogeneity of CD3 and CD8 T-cell densities in the microenvironment of dna mismatch-repair-deficient colon cancers: implications for prognosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:125–133. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swiderska-Chadaj, Z. et al. Convolutional Neural Networks for Lymphocyte detection in Immunohistochemically Stained Whole-Slide Images. (2018).

- 31.Heindl, A. et al. Relevance of spatial heterogeneity of immune infiltration for predicting risk of recurrence after endocrine therapy of ER+ breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110, djx137 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Stoler MH. Advances in cervical screening technology. Mod. Pathol. 2000;13:275–284. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vis JY, Huisman A. Verification and quality control of routine hematology analyzers. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2016;38:100–109. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perkel JM. Immunohistochemistry for the 21st century. Science. 2016;351:1098–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.351.6277.1098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lloyd MC, et al. Using image analysis as a tool for assessment of prognostic and predictive biomarkers for breast cancer: how reliable is it? J. Pathol. Inform. 2010;1:29. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.74186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holten-Rossing H, Møller Talman M-L, Kristensson M, Vainer B. Optimizing HER2 assessment in breast cancer: application of automated image analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015;152:367–375. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3475-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gavrielides MA, Gallas BD, Lenz P, Badano A, Hewitt SM. Observer variability in the interpretation of HER2/neu immunohistochemical expression with unaided and computer-aided digital microscopy. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2011;135:233–242. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-135.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamilton PW, et al. Digital pathology and image analysis in tissue biomarker research. Methods. 2014;70:59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dieci MV, et al. Update on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer, including recommendations to assess TILs in residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy and in carcinoma in situ: a report of the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group on Breast Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018;52:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finotello F, Trajanoski Z. Quantifying tumor-infiltrating immune cells from transcriptomics data. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018;67:1031–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2150-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chakravarthy A, et al. Pan-cancer deconvolution of tumour composition using DNA methylation. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3220. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ács B, et al. Ki-67 as a controversial predictive and prognostic marker in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Diagn. Pathol. 2017;12:20. doi: 10.1186/s13000-017-0608-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi M, et al. Which threshold for ER positivity? a retrospective study based on 9639 patients. Ann. Oncol. 2014;25:1004–1011. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Göranzon C, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of lymphocytes in microscopic colitis. J. Crohns. Colitis. 2013;7:e434–e442. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pagès F, et al. International validation of the consensus Immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: a prognostic and accuracy study. Lancet. 2018;391:2128–2139. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30789-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galon J, et al. Towards the introduction of the ‘Immunoscore’ in the classification of malignant tumours. J. Pathol. 2014;232:199–209. doi: 10.1002/path.4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Väyrynen JP, et al. An improved image analysis method for cell counting lends credibility to the prognostic significance of T cells in colorectal cancer. Virchows Arch. 2012;460:455–465. doi: 10.1007/s00428-012-1232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh U, et al. Analytical validation of quantitative immunohistochemical assays of tumor infiltrating lymphocyte biomarkers. Biotech. Histochem. 2018;93:411–423. doi: 10.1080/10520295.2018.1445290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buisseret L, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte composition, organization and PD-1/ PD-L1 expression are linked in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1257452. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1257452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blom S, et al. Systems pathology by multiplexed immunohistochemistry and whole-slide digital image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:15580. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15798-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gentles AJ, et al. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat. Med. 2015;21:938–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stanton SE, Adams S, Disis ML. Variation in the incidence and magnitude of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer subtypes: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1354–1360. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janowczyk A, Zuo R, Gilmore H, Feldman M, Madabhushi A. HistoQC: an open-source quality control tool for digital pathology slides. JCO Clin. Cancer Inf. 2019;3:1–7. doi: 10.1200/CCI.18.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hipp J, et al. Computer aided diagnostic tools aim to empower rather than replace pathologists: Lessons learned from computational chess. J. Pathol. Inform. 2011;2:25. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.82050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gurcan MN. Histopathological image analysis: path to acceptance through evaluation. Microsc. Microanal. 2016;22:1004–1005. doi: 10.1017/S1431927616005869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fauzi MFA, et al. Classification of follicular lymphoma: the effect of computer aid on pathologists grading. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2015;15:115. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0235-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Madabhushi A, Agner S, Basavanhally A, Doyle S, Lee G. Computer-aided prognosis: predicting patient and disease outcome via quantitative fusion of multi-scale, multi-modal data. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2011;35:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayes DF. Precision medicine and testing for tumor biomarkers-are all tests born equal? JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:773–774. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Selleck, M. J., Senthil, M. & Wall, N. R. Making meaningful clinical use of biomarkers. Biomark. Insights12, 11772719–17715236 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Masucci GV, et al. Validation of biomarkers to predict response to immunotherapy in cancer: Volume I - pre-analytical and analytical validation. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2016;4:76. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0178-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dobbin KK, et al. Validation of biomarkers to predict response to immunotherapy in cancer: volume II - clinical validation and regulatory considerations. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2016;4:77. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0179-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pantanowitz L, et al. Validating whole slide imaging for diagnostic purposes in pathology: guideline from the College of American Pathologists Pathology and Laboratory Quality Center. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2013;137:1710–1722. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0093-CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fda, M. Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff - Technical Performance Assessment of Digital Pathology Whole Slide Imaging Devices. (2016). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/90791/download.

- 64.US Food and Drug Administration. Device Advice for AI and Machine Learning Algorithms. NCIPhub - Food and Drug Administration. Available at: https://nciphub.org/groups/eedapstudies/wiki/DeviceAdvice. (Accessed: 4th July 2017).

- 65.Leo P, et al. Evaluating stability of histomorphometric features across scanner and staining variations: prostate cancer diagnosis from whole slide images. J. Med. Imaging (Bellingham) 2016;3:047502. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.3.4.047502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pantanowitz L, Liu C, Huang Y, Guo H, Rohde GK. Impact of altering various image parameters on human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 image analysis data quality. J. Pathol. Inform. 2017;8:39. doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_46_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pantanowitz L, et al. Twenty years of digital pathology: an overview of the road travelled, what is on the horizon, and the emergence of vendor-neutral archives. J. Pathol. Inform. 2018;9:40. doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_69_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zarella MD, Yeoh C, Breen DE, Garcia FU. An alternative reference space for H&E color normalization. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0174489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herrmann MD, et al. Implementing the DICOM standard for digital pathology. J. Pathol. Inform. 2018;9:37. doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_42_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Eycke, Y.-R., Allard, J., Salmon, I., Debeir, O. & Decaestecker, C. Image processing in digital pathology: an opportunity to solve inter-batch variability of immunohistochemical staining. Sci. Rep. 7, 42964 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Tellez, D. et al. Quantifying the effects of data augmentation and stain color normalization in convolutional neural networks for computational pathology. http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.06543 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Hou, L. et al. Unsupervised histopathology image synthesis. http://arxiv.org/abs/1712.05021 (2017).

- 73.Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE., Jr. Prediction models need appropriate internal, internal-external, and external validation. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016;69:245–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Natrajan R, et al. Microenvironmental heterogeneity parallels breast cancer progression: a histology-genomic integration analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Loi S, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis: a pooled individual patient analysis of early-stage triple-negative breast canc ers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:559–569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beck AH. Open access to large scale datasets is needed to translate knowledge of cancer heterogeneity into better patient outcomes. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Litjens, G. et al. 1399 H&E-stained sentinel lymph node sections of breast cancer patients: the CAMELYON dataset. Gigascience7, giy065 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.US Food and Drug Administration. Year 2: High-throughput truthing of microscope slides to validate artificial intelligence algorithms analyzing digital scans of pathology slides: data (images + annotations) as an FDA-qualified medical device development tool (MDDT). Available at: https://ncihub.org/groups/eedapstudies/wiki/HighthroughputTruthingYear2?version=2.

- 79.Ørting, S. et al. A survey of crowdsourcing in medical image analysis. http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09159 (2019).

- 80.Hannun AY, et al. Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network. Nat. Med. 2019;25:65–69. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0268-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.O’Connor JPB, et al. Imaging biomarker roadmap for cancer studies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017;14:169–186. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Abramson RG, et al. Methods and challenges in quantitative imaging biomarker development. Acad. Radiol. 2015;22:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nalisnik M, et al. Interactive phenotyping of large-scale histology imaging data with HistomicsML. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:14588. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15092-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kwolek, B. et al. Breast Cancer Classification on Histopathological Images Affected by Data Imbalance Using Active Learning and Deep Convolutional Neural Network: 28th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Munich, Germany, September 17–19, 2019, Proceedings. in Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning—ICANN 2019: Workshop and Special Sessions (eds. Tetko, I. V., Kůrková, V., Karpov, P. & Theis, F.) 11731, 299–312 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

- 85.U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Considerations for Design, Development, and Analytical Validation of Next Generation Sequencing-Based In Vitro Diagnostics Intended to Aim in the Diagnosis of Suspected Germline Diseases. (2018). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM509838.pdf.

- 86.Mukherjee A, et al. Associations between genomic stratification of breast cancer and centrally reviewed tumour pathology in the METABRIC cohort. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2018;4:5. doi: 10.1038/s41523-018-0056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cooper LA, et al. PanCancer insights from The Cancer Genome Atlas: the pathologist’s perspective. J. Pathol. 2018;244:512–524. doi: 10.1002/path.5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Anderson R. Multiplex fluorescence in situ hybridization (M-FISH) Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;659:83–97. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-789-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Longuespée R, et al. Tissue proteomics for the next decade? Towards a molecular dimension in histology. OMICS. 2014;18:539–552. doi: 10.1089/omi.2014.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Beck AH, et al. Systematic analysis of breast cancer morphology uncovers stromal features associated with survival. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:108ra113. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cantini L, et al. Classification of gene signatures for their information value and functional redundancy. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 2018;4:2. doi: 10.1038/s41540-017-0038-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meier, A. et al. 77PEnd-to-end learning to predict survival in patients with gastric cancer using convolutional neural networks. Ann. Oncol. 29 10.1093/annonc/mdy269.07510.1093/annonc/mdy269.075 (2018).

- 93.Guidotti R, et al. A survey of methods for explaining black box models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018;51:1–42. doi: 10.1145/3236009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yuan X, He P, Zhu Q, Li X. Adversarial examples: attacks and defenses for deep learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn Syst. 2019;30:2805–2824. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2886017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang Q-S, Zhu S-C. Visual interpretability for deep learning: a survey. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2018;19:27–39. doi: 10.1631/FITEE.1700808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yousefi S, et al. Predicting clinical outcomes from large scale cancer genomic profiles with deep survival models. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11707. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11817-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yi X, Walia E, Babyn P. Generative adversarial network in medical imaging: a review. Med. Image Anal. 2019;58:101552. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2019.101552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]