Abstract

Heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy (HCSP) is very rare, with only 24 cases reported in the literature. Optimal management is yet to be determined. We describe a 38-year-old woman, G2P1, who presented with vaginal bleeding and haemodynamic instability at 9 weeks of gestation in a HCSP. She was managed with ultrasound-guided lower-segment curettage and bilateral uterine artery ligation. The patient's pregnancy was complicated by preterm rupture of membranes and shortened cervix at 27 weeks of gestation. This necessitated preterm delivery, with subsequent neonatal death attributed to extreme prematurity. The patient later had a spontaneously conceived pregnancy, which was complicated by placenta percreta requiring elective caesarean hysterectomy at 34 weeks of gestation. This is, to our knowledge, the first case report describing preservation of the intrauterine pregnancy and future fertility in a patient with a HCSP and significant first-trimester bleeding. We suggest that ultrasound-guided lower-segment curettage may be a suitable management option for carefully selected patients with HCSP in a tertiary centre. All patients with HCSP require judicious counselling regarding the risk of morbidly adherent placenta and need for tertiary-level obstetric management in future pregnancies.

Keywords: Heterotopic pregnancy, Heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy, Caesarean scar pregnancy, Dilation and curettage, Uterine artery ligation

Highlights

-

•

First trimester bleeding in heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy

-

•

Surgical management of heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy

-

•

Ultrasound guided curettage with preservation of concurrent intrauterine pregnancy

1. Introduction

Heterotopic pregnancy is a rare condition associated with an increased risk of maternal or fetal death [1]. Approximately 90% of heterotopic pregnancies are a result of an intra-uterine pregnancy and a co-existing tubal ectopic pregnancy [1]. Heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy (HCSP), where the ectopic pregnancy is implanted into the uterine scar, is extremely rare, with only 24 cases reported in the literature [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]]. Diagnosing HCSP is challenging, as over half of women affected are asymptomatic. However, these presentations are likely to be seen more frequently secondary to increasing rates of both caesarean deliveries and assisted reproductive technologies [26]. There is no standardised approach to management of these patients and evidence to guide clinical management stems from case series and individual reports [26]. The complexity of management arises from the need to consider the viable intra-uterine gestation in addition to the risk of maternal uterine rupture and life-threatening haemorrhage. Furthermore, caesarean scar pregnancy has been recognised as a precursor to morbidly adherent placenta and is associated with placenta accreta in up to 30% of future pregnancies [27].

This article examines research to provide an update on the diagnosis, management and prognosis of HCSP. It also outlines an extremely rare case of emergency surgical management for acute bleeding in a patient with a HCSP. Hospital departmental ethics was waived following written patient consent. A literature review of English publications within the last 20 years was conducted through Ovid MEDLINE and EMBASE databases, using the terms “heterotopic pregnancy” and “c(a)esarean scar pregnancy” or “heterotopic c(a)esarean scar pregnancy”, “uterine artery ligation”.

2. Case Presentation

We describe a 38-year-old woman, gravida 2 para 1, who presented acutely at 9+0 weeks of gestation in a spontaneously conceived pregnancy with heavy vaginal bleeding and signs consistent with hypovolaemic shock. Her obstetric history included one caesarean section for breech presentation three years earlier. Notably, serial ultrasounds between 5 and 8 weeks of gestation in the current pregnancy demonstrated a viable intrauterine pregnancy with a concurrent cystic structure (up to 2 ml volume) in the lower uterine cavity at the site of the caesarean scar. This raised clinical concern for a heterotopic pregnancy with rupture of the non-viable caesarean scar pregnancy. The patient remained unstable despite resuscitation and was consented for an emergency examination under anaesthesia, dilation and curettage, plus or minus a laparotomy, plus or minus a hysterectomy. She expressed a strong desire to preserve the viable intrauterine pregnancy and her uterus.

The patient proceeded immediately to the operating theatre. Repeat bedside ultrasound showed a viable fundal intrauterine pregnancy and lower uterine segment distension, with a large blood clot and ongoing bleeding. An ultrasound-guided suction curettage of the lower segment was performed, with removal of thrombus and products of conception (confirmed on histopathology). Subsequently, a Foley catheter was inserted into the uterus, inflated to 70 ml and placed under traction. Despite this, the patient had persistent bleeding and a decision was made to proceed with a laparotomy. Intra-operatively there was no evidence of uterine scar rupture. Bilateral uterine artery ligation was performed without complication, which led to a significant reduction in the patient's vaginal bleeding. The patient required massive transfusion intra-operatively with six units packed red blood cells and four units of fresh frozen plasma and her haemoglobin was 96 g/L at the close of the case.

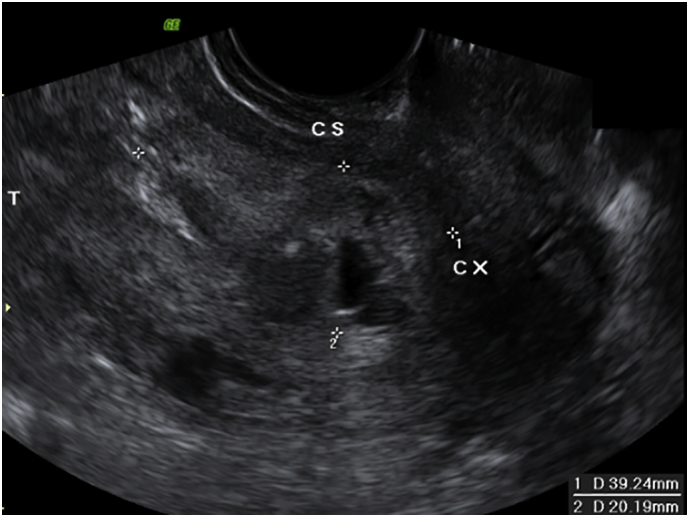

Post-operatively the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for monitoring and the Foley catheter was removed on day 3 post-operatively. She had an ultrasound at 9+4 weeks of gestation, which showed a single live fetus and a heterogenous area in the lower segment of the uterus measuring 61 × 46 × 45 mm (volume 60 ml) (Fig. A1), which was deemed to be consistent with a blood clot. The anterior myometrium was intact throughout its length and there was no free fluid in the pouch of Douglas. The patient was discharged home on day 6 post-operatively and followed up as an outpatient.

Serial ultrasounds between 11 and 20 weeks of gestation demonstrated gradual resolution of the clot at the lower uterine segment to 14x11x5mm (0.4 ml). At 27+0 weeks of gestation the patient was found to have a shortened cervix to 20 mm and was commenced on vaginal progesterone. A serial ultrasound at 27+6 weeks of gestation demonstrated cervical shortening to 11 mm and the patient was subsequently diagnosed with preterm rupture of membranes. Due to the risk of labour and concern about uterine scar rupture, a decision was made to proceed with an emergency lower-segment caesarean section at 28+1 weeks of gestation, following a complete course of antenatal steroids and magnesium sulphate. The caesarean section was uncomplicated; however, the liveborn male infant (1200 g, 56% for gestation) was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit immediately after birth. The neonate unfortunately died on day 3 of life secondary to extreme prematurity, respiratory distress syndrome and bilateral grade three intraventricular haemorrhages.

Two years later the patient had a spontaneously conceived pregnancy, which was complicated by placenta percreta. She underwent an elective laparotomy, classical caesarean section and total abdominal hysterectomy at 34 weeks of gestation, complicated by a 6000 ml intra-operative haemorrhage. The neonate was born in good condition and admitted to the neonatal high-dependency unit for respiratory support. Post-operatively the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for supportive care and both mother and baby were discharged home in a good condition on day 11 post-operatively.

3. Literature Review

A review of the literature revealed 24 case reports of HCSP up until January 2020 (Table 1). The reported incidence of caesarean scar pregnancy is significantly higher in pregnancies that occur through assisted reproductive technology (3 in 100) compared with naturally conceived pregnancies (1 in 30,000) [1]. Despite this, more than half of the reported HCSP examined in this study were spontaneously conceived (13 cases, 54.2%). All 24 cases were diagnosed by transvaginal ultrasound and the majority were asymptomatic.

The treatment of HCSP is dependent upon the patient's desire to preserve the viable intra-uterine pregnancy. When the patient has no desire to retain the intrauterine pregnancy, methods such as systemic or local injection of methotrexate, or dilation and curettage can be used [26]. The treatment of HCSP in women wishing to preserve the intra-uterine gestation can be divided into three main categories: conservative management (if the ectopic fetal cardiac activity disappears spontaneously); selective embryo reduction in situ; and surgical removal of ectopic gestational tissue. Twenty-two women with a HCSP had a desire to preserve the intrauterine gestation, 15 of whom underwent ultrasound-guided selective reduction (potassium chloride +/− methotrexate +/− embryo aspiration), while 3 underwent surgical excision and 4 were expectantly managed. These treatment modalities were associated with successful preservation of the intrauterine pregnancy and live birth via caesarean section in 18 cases [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8],[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20],23] and vaginal birth after caesarean section in 1 case [24]. There is a high prevalence of complications later in pregnancy, including preterm rupture of membranes (2 cases) [2,4], preterm labour (5 cases) [[5], [6], [7],13,15] and antepartum haemorrhage (2 cases) [3,12], as well as massive haemorrhage after the caesarean section (8 cases) [6,7,12,14,[16], [17], [18],23]. Of the other patients reported, one underwent pregnancy termination for fetal malformation at 12 weeks [9], one required hysterectomy to control haemorrhage secondary to selective reduction and embryo aspiration [22] and one had a septic miscarriage at 16 weeks [25].

4. Discussion

This article outlines a complex case where surgical management was utilised for life-threatening haemorrhage in a patient with a HCSP who wished to preserve the intrauterine pregnancy. To our knowledge, there was only one previously published case report of a HCSP with life-threatening first-trimester bleeding. In this case, the patient required a hysterectomy for uncontrollable haemorrhage following selective embryo reduction and aspiration [22]. Therefore, we describe the first case of successful preservation of the intrauterine pregnancy and future fertility in a HCSP with heavy first-trimester bleeding. Ultrasound-guided suction curettage is an effective method for treating first-trimester caesarean scar pregnancy, with a relatively low risk of bleeding requiring blood transfusion or hysterectomy [28]. Although it has not previously been described in the literature, we suggest that ultrasound-guided suction curettage may be a management strategy for patients with HCSP, to allow preservation of the intrauterine pregnancy and future fertility. This should be performed in a tertiary unit, by a specialist gynaecologist, with appropriate resources to manage complications. Careful case selection is imperative and the patient should be consented for intervention surrounding massive haemorrhage, including uterine artery ligation, uterine artery embolization and hysterectomy.

Caesarean scar pregnancies with higher gestation or vascularity on doppler ultrasound are reported to have a greater risk of bleeding secondary to suction curettage and it has been suggested that initial uterine artery embolization (UAE) reduces this risk [28,29]. However, neither UAE nor uterine artery ligation (UAL) have been studied during pregnancy due to the theoretical concern of poor uterine perfusion and adverse fetal outcomes. As such, there is no definitive data regarding the safety of UAL for a concurrent pregnancy. In this case, bilateral UAL to control ongoing vaginal haemorrhage after suction curettage was an effective surgical intervention to control haemorrhage, whilst preserving the uterus. The UAL had no immediate implications for the intrauterine pregnancy and there were no signs of uteroplacental insufficiency, as suggested by the continuation of the pregnancy until 28 weeks of gestation with no signs of fetal growth restriction. We hypothesise that uterine perfusion was maintained through collateral supply via the ovarian and vaginal arteries, or recanalisation of the uterine arteries. In this case, the subsequent neonatal death was attributed to extreme prematurity and, interestingly, 21% of reported HCSP are complicated by preterm labour [[5], [6], [7],13,15]. However, due to theoretical risk of significant harm to the intrauterine pregnancy, it is imperative UAL is carefully considered and further research regarding the safety of UAL in pregnancy is required.

With increasing global rates of caesarean section and utilisation of assisted reproductive technologies we can expect the incidence of caesarean scar pregnancies to increase. In light of this, clinician awareness regarding the significant risk of morbidly adherent placenta in subsequent pregnancies is required [27]. Women who have a caesarean scar pregnancy should be judiciously counselled regarding the implications for future pregnancies, including the risk of morbidly adherent placenta, major intra-operative haemorrhage or hysterectomy at time of repeat caesarean delivery. We recommend a thorough discussion about contraception and timing of subsequent pregnancy prior to discharge. It may be advisable that some women are counselled against future pregnancies, particularly those with other risk factors for morbidly adherent placenta after caesarean section, including a higher number of caesarean sections and high parity [30]. Women who do conceive subsequently should receive their pregnancy care at a tertiary centre and their first-trimester ultrasound should be performed by an experienced sonographer and assessed for both caesarean scar pregnancy and placenta accreta.

Management strategies for these complex HCSP cases continue to evolve with an increasing number of cases detailed in the literature. Paramount to any management plan is patient safety, careful counselling and documentation of potential adverse outcomes. Ultrasound-guided surgical management with UAL was successful in managing bleeding and preserving the intra-uterine pregnancy in this case. This provides an example of surgical management that can be applied to carefully selected cases with access to tertiary care in the future. Above all, safe and appropriate follow-up for all patients with HCSP is critical to ensure no significant ongoing morbidity and mortality in both the current pregnancy and any subsequent pregnancies.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

Zoe Laing-Aiken is the primary author of this paper and was involved in all aspects of the project.

Danielle Robson contributed to writing the paper.

Joyce Wu contributed to writing the paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this case report.

Funding

No funding was sought or secured in relation to this case report.

Patient consent

Obtained.

Provenance and peer review

This case report was peer reviewed.

Appendix A

Fig. A1.

Ultrasound post-curettage (at 9+4 weeks of gestation) demonstrating a blood clot in the lower segment of the uterus measuring 61 × 46 × 45 mm (volume 60 ml).

Table 1.

All published heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy case reports.

| Author/Year of publication | Maternal age | G/P | No. of previous CS | Conception | GA at diagnosis | Presenting Symptoms | Treatment modality | Details of treatment | Pregnancy outcome | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salomon et al. 2003 | 36 | 4/1 | 1 | IVF ET | 6 | No | Selective reduction | KCl injection | Live birth by CS at 36 weeks due to PROM | No |

| Jurkovic et al. 2003 | 36 | 10/3 | 3 | Spontaneous | 7 | No | Selective reduction | KCl injection | Live birth by CS at 31 weeks due to vaginal haemorrhage | No |

| Yazicioglu et al. 2004 | 23 | 2/1 | 1 | Spontaneous | 6 + 2 | Vaginal bleeding | Selective reduction | KCl injection | Live birth by CS at 30 + 3 weeks due to PROM | No |

| Hsieh et al. 2004 | 38 | 4/2 | 2 | IVF ET (triplets) | 5 | No | Selective reduction | Embryo aspiration | Live twin birth by CS at 32 weeks due to preterm labour | No |

| Wang et al. 2007 | 38 | 4/3 | 3 | IVF ET | 6 | No | Selective reduction | KCl injection | Live birth by CS at 35 weeks due to preterm labour | PPH managed by bilateral internal iliac ligation |

| Taskin et al. 2009 | 24 | 2/1 | 1 | Spontaneous | 8 + 4 | Vaginal bleeding | Selective reduction | KCl injection | Live birth by CS at 34 weeks due to preterm labour | PPH |

| Demirel et al. 2009 | 34 | 2/1 | 1 | Spontaneous | 6 + 5 | Vaginal bleeding | Surgical excision | Laparoscopic excision | Live birth by CS at 38 weeks | No |

| Gupta et al. 2010 | 37 | ?/4 | 4 | IVF ET | 6 + 1 | No | Selective reduction | Embryo aspiration | Pregnancy termination at 12 weeks due to fetal malformation | No |

| Wang et al. 2010 | 31 | 3/1 | 1 | IVF ET | 7 | Vaginal bleeding | Surgical excision | Hysteroscopic excision | Live birth by CS at 39 weeks | No |

| Duenas-Garcia and Young 2011 | 34 | 5/3 | 3 | Spontaneous | 5 | No | Pregnancy termination | Pregnancy termination by methotrexate | No | |

| Litwicka et al. 2011 | 31 | 2/1 | 1 | IVF ET | 6 | Vaginal bleeding and uterine contractions | Selective reduction | KCl and methotrexate injection | Live birth by CS at 36 weeks due to placenta abruption | PPH |

| Bai et al. 2012 | 37 | 2/1 | 1 | IVF ET | 7 + 6 | No | Expectant management | Live birth by CS at 36 + 4 due to preterm labour | No | |

| Ugurlucan et al. 2012 | 34 | 3/1 | 1 | OI | 6 | No | Selective reduction | KCl injection and embryo aspiration | Live birth by CS at 38 weeks | PPH managed by bilateral internal iliac artery ligation and subtotal hysterectomy |

| Uysal and Uysal 2013 | 29 | 3/2 | 2 | Spontaneous | 8 | No | Selective reduction | KCl injection | Live birth by CS at 35 weeks due to preterm labour | No |

| Kim et al. 2014 | 34 | 5/2 | 2 | Spontaneous | 5 | No | Expectant management | Ectopic CSP migrated into lower uterine segment at 8 weeks | Live twin delivery at 37 weeks by CS | PPH due to placenta accreta requiring excision of anterior lower uterine segment and UAL |

| Lui et al. 2014 | 36 | 2/1 | 1 | OI + intrauterine insemination | 5 | Vaginal bleeding | Selective reduction | Embryo aspiration | Live birth at 37 by CS | PPH, managed by UAE |

| Yu et al. 2016 | 33 | 2/1 | 1 | IVF ET | 8 | No | Selective reduction | KCl injection at 16 + 4 | Live birth at 37 + 6 by CS | PPH due to ectopic placenta accrete and placenta praevia |

| Vetter et al. 2016 | 29 | 4/1 | 1 | Spontaneous | 5 | Vaginal bleeding | Surgical excision | Open resection | Live birth at 37 + 1 CS | No |

| Czuczwar et al. 2016 | 33 | 1 | Spontaneous | 6 | No | Selective reduction | KCl injection | Live birth at 37 by CS | No | |

| Eftekhariyazdi et al. 2017 | 34 | 5/2 | 2 | Spontaneous | 7 | Vaginal bleeding | Nil | Pregnancy termination with misoprostol then dilation and curettage | Haemorrhage, managed by emergency total abdominal hysterectomy | |

| Miyague et al. 2018 | 27 | 2/1 | 1 | Spontaneous | 6 | No | Selective reduction | KCl injection and embryo aspiration | Attempted laparoscopic dissection, converted to hysterectomy. | Haemorrhage |

| Yin et al. 2018 | 33 | 4/1 | 1 | IVF ET | 9 + 3 | No | Expectant management | Live birth by CS at 35 + 6 due to placenta praevia and DFM | PPH | |

| Vikhareva et al. 2018 | 27 | 2/1 | 1 | Spontaneous | 11 | No | Expectant management | Live birth by NVD at 37 weeks with oxytocin augmentation | No | |

| Tymon-Rosario et al. 2018 | 40 | 5/3 | 2 | Spontaneous | 11 + 0 | No | Selective reduction | KCl injection | Septic abortion at 16 weeks, uterine artery ligation and D&C | Haemorrhage |

Key: G/P gravity/parity; GA gestational age; CS caesarean section; IVF ET in vitro fertilisation embryo transfer; OI ovulation induction; KCl potassium chloride; PROM preterm rupture of membranes; NVD normal vaginal delivery; DFM decreased fetal movements; UAE uterine artery embolization; UAL uterine artery ligation;PPH post-partum haemorrhage.

References

- 1.Hewlett K., Howell C.M. Heterotopic pregnancy: simultaneous viable and nonviable pregnancies. JAAPA. 2020 Mar;33(3):35–38. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000654012.56086.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salomon L.J., Fernandez H., Chauveaud A., Doumerc S., Frydman R. Successful management of a heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy: potassium chloride injection with preservation of the intrauterine gestation: case report. Hum. Reprod. 2003 Jan;18(1):189–191. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurkovic D., Hillaby K., Woelfer B., Lawrence A., Salim R., Elson C.J. First-trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;21(3):220–227. doi: 10.1002/uog.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yazicioglu H.F., Turgut S., Madazli R., Aygün M., Cebi Z., Sönmez S. An unusual case of heterotopic twin pregnancy managed successfully with selective feticide. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2004 Jun;23(6):626–627. doi: 10.1002/uog.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh B.-C., Hwang J.-L., Pan H.-S., Huang S.-C., Chen C.-Y., Chen P.-H. Heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy combined with intrauterine pregnancy successfully treated with embryo aspiration for selective embryo reduction: case report. Hum. Reprod. 2004 Feb;19(2):285–287. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C.-N., Chen C.-K., Wang H.-S., Chiueh H.-Y., Soong Y.-K. Successful management of heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy combined with intrauterine pregnancy after in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer. Fertil. Steril. 2007;88(3) doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.192. Sep 1. (706.e13–706.e16) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taşkin S., Taşkin E.A., Ciftçi T.T. Heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy: how should it be managed? Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2009 Oct;64(10):690–695. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181b8b144. (quiz 697) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demirel L.C., Bodur H., Selam B., Lembet A., Ergin T. Laparoscopic management of heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy with preservation of intrauterine gestation and delivery at term: case report. Fertil. Steril. 2009;91(4) doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.067. Apr. (1293.e5–7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta R., Vaikousi E., Whitlow B. Heterotopic caesarean section scar pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010;30(6):626–627. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2010.491565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C.-J., Tsai F., Chen C., Chao A. Hysteroscopic management of heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy. Fertil. Steril. 2010;94(4) doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.039. Sep. (1529.e15–8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dueñas-Garcia O.F., Young C. Heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy associated with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011;114(2):153–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litwicka K., Greco E., Prefumo F., Fratelli N., Scarselli F., Ferrero S. Successful management of a triplet heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy after in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Fertil. Steril. 2011;95(1) doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.025. Jan. (291.e1–3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai X.-X., Gao H.-J., Yang X.-F., Dong M.-Y., Zhu Y.-M. Expectant management of heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy. Chin. Med. J. 2012 Apr;125(7):1341–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ugurlucan F.G., Bastu E., Dogan M., Kalelioglu I., Alanya S., Has R. Management of cesarean heterotopic pregnancy with transvaginal ultrasound–guided potassium chloride injection and gestational sac aspiration, and review of the literature. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2012 Sep 1;19(5):671–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uysal F., Uysal A. Spontaneous heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy: conservative management by transvaginal sonographic guidance and successful pregnancy outcome. J. Ultrasound Med. 2013 Mar;32(3):547–548. doi: 10.7863/jum.2013.32.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim M.-L., Jun H.S., Kim J.Y., Seong S.J., Cha D.H. Successful full-term twin deliveries in heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy in a spontaneous cycle with expectant management. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014;40(5):1415–1419. doi: 10.1111/jog.12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lui M.-W., Shek N.W.M., Li R.H.W., Chu F., Pun T.-C. Management of heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy by repeated transvaginal ultrasonographic-guided aspiration with successful preservation of normal intrauterine pregnancy and complicated by arteriovenous malformation. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014;175:209–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu H., Luo H., Zhao F., Liu X., Wang X. Successful selective reduction of a heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy in the second trimester: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016 Nov 29;16(1):380. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1171-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vetter M.H., Andrzejewski J., Murnane A., Lang C. Surgical management of a heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy with preservation of an intrauterine pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):613–616. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Czuczwar P., Stępniak A., Woźniak A., Woźniak S., Paszkowski T. Successful treatment of spontaneous heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy by local potassium chloride injection with preservation of the intrauterine pregnancy. Ginekol. Pol. 2016;87(10):727. doi: 10.5603/GP.2016.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eftekhariyazdi M., Moghaddam M.Y., Souizi B., Mortazavi F. Heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy in a non-assisted fertility: a case report. Iran Red. Crescent. Med. J. [Internet] 2017;19(9) http://ircmj.com/en/articles/60000.html Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyague A.H., Chrisostomo A.P., Costa S.L., Nakatani E.T., Kondo W., Gomes C.C. Treatment of heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy complicated with post termination increase in size of residual mass and morbidly adherent placenta. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2018 Mar;46(3):227–230. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin Q., OuYang Z., Li H., Zhong M., Quan S. Expectant management of heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy: a case report. J. Reprod. Med. 2018 Aug;63(8):397–401. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vikhareva O., Nedopekina E., Herbst A. Normal vaginal delivery at term after expectant management of heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy: a case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2018 Jun 21;12(1):179. doi: 10.1186/s13256-018-1713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tymon-Rosario J., Chuang M. Selective reduction of a heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy complicated by septic abortion. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018 Oct 21;2018:6478589. doi: 10.1155/2018/6478589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.OuYang Z., Yin Q., Xu Y., Ma Y., Zhang Q., Yu Y. Heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. J. Ultrasound Med. 2014 Sep;33(9):1533–1537. doi: 10.7863/ultra.33.9.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drever N., Bertolone J., Shawki M., Janssens S. Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: Experience from an Australian tertiary centre. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.1111/ajo.13119. Jan 15; Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jurkovic D., Knez J., Appiah A., Farahani L., Mavrelos D., Ross J.A. Surgical treatment of Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided suction curettage. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016;47(4):511–517. doi: 10.1002/uog.15857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tumenjargal A., Tokue H., Kishi H., Hirasawa H., Taketomi-Takahashi A., Tsushima Y. Uterine artery embolization combined with dilation and curettage for the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy: efficacy and future fertility. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2018 Aug;41(8):1165–1173. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-1934-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martimucci K., Bilinski R., Perez A.M., Kuhn T., Al-Khan A., Alvarez-Perez J.R. Interpregnancy interval and abnormally invasive placentation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019 Feb;98(2):183–187. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]