Abstract

Background

Bangladesh has established more than 13,000 community clinics (CCs) to provide primary healthcare with a plan of each covering a population of around 6,000. The inception of CCs in the country has revolutionized the healthcare delivery to reach the doorstep of people. The provision of healthcare through CCs is truly participatory since the community people donate land for building infrastructure and also involve in management process. The study was conducted to assess pattern of public private partnership in healthcare delivery through participation of community people in establishment, management, monitoring and utilization of community clinics.

Methods

This quantitative study involving descriptive cross sectional design included 63 healthcare providers, 2,238 service-users and 3,285 community people as household members. Data were collected by face-to-face interview and reviewing records of CCs with the help of semi-structured questionnaire and checklist respectively. The public private partnership was assessed in this particular study by finding community participation in different activities of CCs. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Almost all (96.9%) CCs are located in easy-to-reach areas and have good infrastructure. Lands of all CCs are donated by the respective communities. The security of most of the CCs (93.7%) is maintained by community people. Cleanliness of the CCs is maintained by the cleaners or ayas who are appointed by local communities. Community Groups (CGs) of 88.9% and Community Support Groups (CSGs) of 96.8% CCs are found to be active. In most of the CCs (98.4%), monitoring is done by analysis of monthly reports. All CCs provide referral services for pregnant women. Health care delivery is found to be ‘good’ in more than three-fourths while health education service is ‘good’ in 96.7% of CCs. All CCs showed an increased trend in the utilization of services and conduction of normal child deliveries. Benefits of CCs as perceived by service users included free drugs (82.1%), free treatment (81.2%), easy access (76.3%), need-based health services (75.0%), and immunization services (68.6%). Almost all (99.0%) of the CC service users opined that CGs are involved in management of CC activities.

Conclusion

In resource-poor settings of developing countries, public private partnership in primary healthcare delivery through community clinics may play crucial role in sustainable development of community health by providing quality health care. The study recommends public-private partnership for strengthening CCs including establishment, maintenance, utilization, monitoring and supply of essential drugs and logistics.

Keywords: Quality of life, Epidemiology, Pregnancy, Reproductive system, Health education, Inequality, Community clinics, Community participation, Health service delivery, Health service utilization, User satisfaction, Public private partnership

Quality of Life; Epidemiology; Pregnancy; Reproductive System; Health Education; Inequality; Community Clinics, Community Participation, Health Service Delivery, Health Service Utilization, User Satisfaction, Public Private Partnership.

1. Introduction

Community clinic (CC) is a revolutionary initiative to provide basic health care services in the rural communities of Bangladesh. The CCs are the primary level health facilities have been established and functioning by the government along with participation of local communities. Empirical research on the role of community participation in management of community clinics in Bangladesh has hardly been conducted. Some studies in other countries have been done on community participation in primary healthcare but, in Bangladesh, literature surrounding community clinics is limited to newspaper articles, minutes if meetings, proceedings of seminars, workshops, and symposia. The scholarly articles related to public private partnership through community participation in operating community clinic services is very scarce in Bangladesh.

Community participation is an essential part of promoting health as it is "a means of organizing action and motivating individuals and communities" and it helps people to shape policies and projects to meet their priorities [1]. It is an important means of changing people's attitude and actions towards promoting a sense of responsibility in any interventions and this behavioural change is consistent with the community norms and re-affirms the role of people in managing their own health [2]. Based on this premise, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), in the Alma Ata Declaration in 1978, emphasized the participation of community people in primary healthcare. Since then, 150 Member States of the WHO and UN are committed to promoting people's participation in the management of healthcare facilities at the community level. It was intended to revolutionize the health systems development for achieving the aim of “health for all by the year 2000” [3]. Moreover, universal health coverage is the major target of sustainable development goal (SDG-3). To achieve the target, cooperation, collaboration and partnership between private and public sector is needed [4].

High income countries have a set of institutionalized policy instruments for managing the private sector whereas in middle and low income countries, the situation is more challenging as the private sector is expanding rapidly there. Those resource poor countries demand development and implementation of appropriate healthcare delivery policy, regulatory instruments and skill workforce [4]. Country specific research is necessary to find out the better alternative of health service delivery including public-private partnership in those resource poor countries.

Following the lessons learnt from a study in South Australia [5] and China [6], a study was conducted in Bangladesh on the involvement of community people in delivery and management [7].While the studies in both South Australia and China were conducted in urban settings, the one in Bangladesh explored the situation in a rural setting. The study emphasized more on the delivery of Essential Service Package (ESP) in the rural communities than on the overall functionalities of the CCs. The study, however, suggested that development of an appropriate behavior change communication (BCC) program, integration of interpersonal communication channels with the print and electronic media. Demonstration and advocacy workshops are also essential to establish public-private partnership (PPP) through community participation and mobilization for effective operation of the CCs. With this realization, the Government of Bangladesh has been designing its sector-wide programs to ensure access of all people to basic healthcare services. Special emphasis has paid on the participation of rural people in the planning, establishment, and management of community clinics [8, 9]. The same attempts are being continued in the current sector-wide program called the 4th Health, Population and Nutrition Development Program (2017–2022).

CC turns the concept of PPP into reality as all CCs are constructed on lands donated by community people; costs relating to construction, medicines, and all necessary logistics, salaries of service providers are met from the government revenues and development funds but the management is done by the community people, unlike the next two tiers of primary healthcare facilities: union sub-centers (USCs) and upazila health complexes (UHCs) that are fully run by the Government.

Each CC is headed by a community healthcare provider (CHCP) who works 6 days a week; a health assistant (HA) and a family welfare assistant (FWA) work alternatively 3 days a week. Community Group (CG) is pivotal in the management of CC. Each Community Group (CG) consists of 13–17members, headed by the elected Union Parishad (UP) Member. In the catchment area of each CC, there are three Community Support Groups (CSGs) each comprising of 13–17members [9].

Since liberation in 1971, the Government of Bangladesh has taken different initiatives for decentralization of health services through establishing upazila (sub-district) health complexes with a vision to extend health services to the grassroots-level in phases and was moving forward with its own strategy to achieving “health for all” [10, 11]. However, Bangladesh had to face a number of challenges for unavailability of resources and inaccessibility of primary-level healthcare to the vast rural community comprising of three-quarters of the population. This realization led to the establishment of CCs to extend Essential Service Package to the doorsteps of rural people [9, 12].

Bangladesh has achieved remarkable success in the health sector and received international awards for reduction of child mortality and improvement of maternal health; life-expectancy, access to safe water and sanitation have increased; poverty and malnutrition have reduced, and quality of life has improved remarkably [9].

An in-depth assessment of the pattern and effects of community participation in health service delivery through this CC approach was essential for further improvement of these grassroots-level tiny health facilities and dissemination of this model to the global community for probable replication in other developing countries. The present study, for the first time, has done this comprehensively. Specific objectives of the study were to assess community participation in: (i) establishment and maintenance of CCs in rural Bangladesh; (ii) management and monitoring of CC activities; (iii) determining quality of physical facilities and healthcare services of the CCs; and (iv) utilization of CC services along with satisfaction of the users.

As a pioneering work, this study laid the foundation for further investigations into the public-private partnership in terms of community participation in the delivery of primary healthcare services at the doorsteps of rural people. The study findings are expected to open an avenue for policy-makers and health managers in Bangladesh and elsewhere in the developing world to understand the pattern of public-private partnership through community participation in healthcare delivery to rural people. This study has made an in-depth assessment of the community participation in healthcare delivery through the CC approach in the rural context of Bangladesh. The study findings on public-private partnership through community participation in basic health care delivery by CCs will contribute to achieve global health goal ‘health for all’ and ‘universal health coverage’.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

The study was a quantitative study and involved descriptive cross-sectional design. The public-private partnership was assessed in this study by finding community participation in different activities including establishment, management, monitoring and utilization of CCs.

2.2. Study period

The study was conducted during the period of 2011–2018 as the thesis of PhD program. Data were collected during the period of 2016–2017. Before that scientific approval and ethical clearance were obtained through specific procedure. As a prerequisite, course work on thesis and scientific seminar were performed by the principal investigator.

2.3. Study population

In addition to the selected community clinics (CCs), the study population comprised of patients attending CCs and adult community people.

2.4. Inclusion criteria

-

•

The CCs were selected randomly.

-

•

Administrative permission was obtained from the Directorate General of Health Services informing respective civil surgeons and upazila health and family planning officers.

-

•

Participants were included by taking informed written consent from each.

-

•

Adult household members aged ≥18 years irrespective of sex were selected.

2.5. Exclusion criteria

-

•

Participants who were severely ill both physically and mentally.

-

•

Visitors or tourists to the communities and community clinics.

2.6. Sample size

The sample-size was calculated for the household survey by using the formula:

n = z2pq/d2where: n = desired sample-size;

p = 0.5 (as there was no estimate of the prevalence rate of community participation for household survey, we were assuming 50% level of community participation for this survey);

q = 1-p = 1–0.5 = 50%;

d = degree of error (absolute precision of the study assumed to be 0.05); and

z = reliability coefficient at the 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.96.

Thus, the required sample-size for the household survey was

n = z2pq/d [2]=(1.96)2 × 0.5 × 0.5÷(0.05)2 = 384 in each district.

In total, 16 districts were selected randomly from eight divisions (2 districts from each division). A total of 5,504 participants from 16 districts (344 from each district) were included in the study. Total 32 community clinics (2 from each district) and, 172 participants from each community were included. Participants included: community healthcare providers (CHCPs), health assistants (HAs), family welfare assistants (FWAs), household members. At the community level, one participant from each household (household member) was randomly included in the study. Therefore, the total sample-size was 5,504 participants and 32CCs. Out of 172 participants in each community, 2 CHCPs/HAs/FWAs, 70 patients and 100 household members were included. Considering availability, response rate and other constraints the study included 63 healthcare providers, 2,238 service-users and 3,285 community people as household members.

2.7. Sampling

The study selected the study participants following multistage sampling technique.

The study was conducted in the randomly-selected rural areas of the eight administrative divisions of Bangladesh. The study was conducted using multistage sampling technique. At first, 16 districts (2 from each division) were selected randomly from 8 administrative divisions of Bangladesh. Secondly, 32 CCs (2 from each district) were selected randomly from those 16 districts.

The patients were selected randomly using systematic random sampling technique using a skip interval at the CCduring weekly visits. On the basis of number patients attending in each day and number of patients to be included in study in that respective day from each CC, sampling interval was calculated and accordingly patients were included randomly following that sampling interval.

The household members were selected randomly using systematic random sampling technique at the community kevel. In this case, household number (GR) was used. On the basis of number of households and number of participants to be included in from each community, sampling interval was calculated and following that sampling interval, participants were selected randomly.

2.8. Data-collection instruments

-

➢

Under the quantitative study design, data were collected with the help of a semi-structured questionnaire and checklist. The questionnaire was developed consisting of demographic/socioeconomic status, such as age, gender, education, employment status, household possession, utilization of healthcare, quality of CC facilities and services, reasons behind non-utilization of healthcare facilities, pattern of utilization in respect of type and pattern of health problems, pattern of community participation in different dimensions of CCs.

-

➢

All the instruments were developed as draft followed by pretest done in two CCs and in the catchment areas other than the study site. For pretest, one CC was selected from Sreepur upazila and another from Kaliakair upazila of Gazipur district. The data-collection instruments were finalized by necessary corrections and modifications following findings from the pretest.

2.9. Data-collection procedure

-

➢

Descriptive survey: Data on logistics and physical facilities, human resources, political and administrative services of the community clinics were collected by face-to-face interview under the cross-sectional study design.

-

➢

Patients' survey: Data were collected from the patients by face-to-face interview at the community clinic during weekly visits.

-

➢

Care providers' survey: Data were collected from the healthcare providers by face-to-face interview at the community clinic.

-

➢

Household survey: Data were collected from the household members by face-to-face interview at the community level

2.10. Data processing

The collected data were checked, verified, categorized, coded, and then entered into the computer for analysis with the help of SPSS software. Any inconsistency and irrelevance with data were checked carefully and corrected accordingly.

2.11. Data analysis

Data were analyzed with the help of SPSS software. Descriptive analyses were done to relate the participation with selected characteristics. Non-response from any patient was excluded from the final analysis. The data analysis and data gathering were done simultaneously. Descriptive statistics included mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage.

2.12. Ethical consideration

There was no risk on the study population as there was no hazardous procedure involved in the study. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study. There was neither any loss of working hours of the study population nor physical invasive procedure with the participants. Initially, the ethical clearance for the study was obtained from Bangladesh Medical Research Council (BMRC). Before interview, informed written consent was obtained from each participant and all the participants were also briefed about the objectives and detailed procedures of the study; their voluntary participation in the study was sought.

3. Results

3.1. Community participation in the establishment and maintenance of CCs

Table 1 reveals that, for 22 CCs (68.8%) out of 32 under this study, the CG members donated land and, in the remaining 10 (31.3%) CCs, local members of the community donated land.

Table 1.

Community participation in establishment and maintenance of CCs.

| Attribute | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Establishment of CCs | ||

| Land donation | ||

| Community Group (CG) members | 22 | 68.7 |

| Local community members |

10 |

31.3 |

| 2. Maintenance of CCs | ||

| Community Support Group (CSG) to support CG | ||

| Active | 61 | 96.8 |

| Inactive | 02 | 3.2 |

| Chief patron of the CSG | ||

| UP chairman | 37 | 58.7 |

| Other | 26 | 41.3 |

| Member Secretary of CSG | ||

| CHCP | 61 | 96.8 |

| Other member | 02 | 3.2 |

| Training of CSG members based on training manual & guide | ||

| Yes | 52 | 82.5 |

| No | 11 | 17.5 |

| Cleanliness of the CC is maintained by | ||

| Cleaners from community clean the clinic | 24 | 38.1 |

| CG/CSG supervises the cleanliness | 21 | 33.3 |

| Aya from community cleans the CC | 26 | 41.3 |

| Don't know | 1 | 1.6 |

| Frequency of visits of the FWA/HA to the CC | ||

| Never | 2 | 3.2 |

| Once in a week | 7 | 11.1 |

| Twice in a week | 14 | 22.2 |

| Thrice in a day | 40 | 63.5 |

| Security of CC is maintained by | ||

| Guard | 2 | 6.2 |

| Lock and key after working hours | 16 | 50.0 |

| Persons engaged by CG or neighboring households | 8 | 25.0 |

| Local people | 6 | 18.8 |

Almost all, 96.8% CCs had Community Support Group (CSG) to support community group (CG). In 96.8% cases, CHCP were member secretary of CSG and in 58.7% cases, UP chairman was the chief patron of the CG. About 83% opined that CSG members were trained following training manual & trainer's guide. It was revealed that in the CCs, cleanliness was ensured mostly by ‘Aya’ (41.3%) and ‘Cleaner’ (38.1%). In 33.3% cases, CG/CSG supervised the cleanliness activities. In 63.5% cases, the FWA/HA came to the CC for providing services thrice in a day, 3.2% never came and 11.1% and 22.2% came once in a week and twice in a week respectively. For security of the CCs, only 2 CCs had night guards; 16 were being kept under lock and key at night time; and security of the remaining 14 were maintained either by persons engaged by CG members and neighboring households, or by local people.

3.2. Community participation in management and monitoring of CC activities

3.2.1. Community participation in management of CCs

Table 2 shows structure and role of the Community Group (CG). Quite a large number of the CCs (88.9%) had effective and functioning CG for management of the CC while 11.1% CGs were inactive. In the CCs with inactive CG, 28.6% reported that it was not formed properly, and 71.4% did not know the reason. The posts of member secretary and chief patron of the CG were regarded very important. In most cases (96.8%), CHCP was the member secretary of CG and in more than half of cases (58.7%), UP chairman was the chief patron of the CG. Most (92.1%) of the CG members were trained following training manual & trainer's guide. Most of the CG members (85.7%) met once in a month.

Table 2.

Community participation in management of CCs.

| Attribute | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

CG for Management of the CC | ||

| Active | 56 | 88.9 |

| Inactive |

07 |

11.1 |

|

Reasons for inactivity | ||

| Improperly formed | 02 | 28.6 |

| Did not know |

05 |

71.4 |

|

Member Secretary of CG | ||

| CHCP | 61 | 96.8 |

| Other member |

02 |

3.2 |

|

Patron of the CG | ||

| UP chairman | 37 | 58.7 |

| Other member |

26 |

41.3 |

|

Training of CG members based on training manual & guide | ||

| Yes | 58 | 92.1 |

| No |

05 |

7.9 |

|

How often the CG members meet | ||

| Once in week | 07 | 11.1 |

| Once in a month | 54 | 85.7 |

| Every 3 months | 01 | 1.6 |

| Once in a year | 01 | 1.6 |

3.2.2. Community participation in monitoring of CCs

Table 3 shows that, monitoring for CC activities is done by higher authorities at the monthly meetings at the union, upazila (sub-district), district, and division level based on monthly reports (98.4%) and/or direct online communication (90.5%). Routine visits to CCs by government/non-government organizations and representatives from development partners are also made for monitoring of the CC activities (82.5%).

Table 3.

Monitoring of community clinic activities.

| Way of monitoring | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly report analysis | 62 | 98.4 |

| Routine CC visit by G0, NGOs & DPs of different tiers with specific checklist | 52 | 82.5 |

| Mobile tracking of service providers from HQ | 53 | 84.1 |

| Monthly meeting at division, district, Upazila, union level taking CC issue as top most prioritized agenda | 54 | 85.7 |

| Online report communication through internet | 57 | 90.5 |

3.3. Quality of physical facilities and health care services of the CCs

3.3.1. Physical facilities of CCs

Table 4 provides information regarding the infrastructural facilities of the sampled CCs. Of the 32 CCs under study, 31 had government-approved size (450 sq. ft); only 1 CC was smaller than the approved size. Quality of construction of the CCs, on an average, was good. Quality of doors was good in almost all CCs (96.9%); quality of windows was good in slightly more than four-fifths of the CCs (81.3%) but quality of roofs was good in less than two-thirds of the CCs (62.5%); 81.2% of the CCs consisted of two rooms, and the rest 18.8% had three rooms. More than two-thirds (68.8%) of the CCs had only one latrine while 31.2% had two latrines. For safe drinking-water supply, only 10 (31.2%) had tube wells in functioning condition; 20 (62.5%) CCs had tube wells installed but not functioning; 2 (6.3%) CCs did not have any tube wells. Almost all CCs (30) had waiting space for patients well-furnished with benches and other seating facilities. In only 2 CCs, patients had to remain standing. Only 18 (56.3%) CCs had electric connection. For providing care, 27 CCs (84.4%) had sufficient number of chairs/tables; only 8 CCs (25.0%) of the 32 CCs had hotline numbers for communication but, in one CC, the hotline number was found inactive. Availability of HAs (59.40%) and FWAs (46.90%) were low whereas CHCPs were available in most (90.60%) of the CCs.

Table 4.

Quality of physical facilities of CCs (n=32).

| Attribute | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

Size of community clinics | ||

| Government-approved size (450 sq. ft) | 31 | 96.9 |

| Smaller than approved size |

1 |

3.1 |

|

Quality of construction of CCs | ||

| Good door quality | 31 | 96.9 |

| Good window quality | 26 | 81.3 |

| Good roof quality |

20 |

62.5 |

|

Number of rooms in CCs | ||

| Two | 26 | 81.2 |

| Three |

6 |

18.8 |

|

Number of latrines | ||

| One | 22 | 68.8 |

| Two |

10 |

31.2 |

|

Condition of latrines | ||

| Clean | 16 | 50.0 |

| Dirty |

16 |

50.0 |

|

Condition of tube wells installed at CCs | ||

| Prevalent and functioning | 10 | 31.2 |

| Prevalent but not functioning | 20 | 62.5 |

| Do not have any tube wells |

2 |

6.3 |

|

Waiting space for patients | ||

| Well-furnished with benches and other seating facilities | 30 | 93.7 |

| No seating facilities (patients remain standing) |

2 |

6.3 |

|

Electricity supply at CCs | ||

| Present |

18 |

56.3 |

|

Sufficiency of chairs/tables for care providers | ||

| Sufficient |

27 |

84.4 |

|

Any hotline number at CCs | ||

| Present |

8 |

25.0 |

|

Whether the hotline is active (n=8) | ||

| Yes |

7 |

21.9 |

|

Presence of night guard at CCs | ||

| Yes | 2 | 06.3 |

| No | 30 | 93.7 |

3.4. Quality of health care services provided by CCs

Table 5 provides information regarding quality of health care services provided by the community clinics. The grading of the CCs and facilities were done on the basis of preset criteria; total score of all relevant attributes, where ‘good’ was graded when the score was ≥80% while ‘average when the score was between 50-79% and ‘poor’ when the score was <50% of the total score.

Table 5.

Quality of health care services.

| Attributes | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

Quality of equipment | ||

| Good | 4 | 12.5 |

| Average | 26 | 81.3 |

| Poor |

2 |

6.3 |

|

Quality drug supply services | ||

| Good | 13 | 40.6 |

| Average | 10 | 31.3 |

| Poor |

9 |

28.1 |

|

Quality of furniture and logistics | ||

| Good | 20 | 62.5 |

| Average | 8 | 25.0 |

| Poor |

4 |

12.5 |

|

Quality of health care | ||

| Good | 25 | 78.1 |

| Average |

7 |

21.9 |

|

Quality of health education | ||

| Good | 31 | 96.9 |

| Average | 01 | 3.1 |

3.5. Availability of equipment in CCs

The study assessed sufficiency of equipment, including (i) primary medical kits (scissors, forceps), (ii) blood pressure instrument with stethoscope, (iii) tool kits (gauge, masks, thermometers, timers, sensor kits), (iv) insecticides spraying machine, (v) bathroom scale, (vi) kerosene stove, (vii) hanging scale (viii) umbo bag and penguin sucker, (ix) urinary catheter, (x) syringe, (xi) vaginscope, (xii) flash-cards named ‘Sonali Alo’, and (xiii) others available in the CCs. Each of the equipment was assigned a score in the following way:

Score = 2 if supply was sufficient and condition was perfect; score = 1 if supply was insufficient and condition was perfect or supply was sufficient but condition was not good; score = 0 if supply was insufficient and condition was not good. The total score for the availability of equipment for each CC was calculated. CCs were then graded as ‘poor’, ‘average’, and ‘good’ according to the preset criteria. Only 4 CCs (12.5%) were of the ‘good’ category, more than four-fifths (81.3%) were of ‘average’ and 6.3% were of ‘poor’ category.

3.6. Drug supply services at CCs

To find the state of drug supply services, attributes such as (i) availability of all essential drugs, (ii) supply of essential drugs in due time, (iii) sufficiency in terms of the quantity of essential drugs supplied, (iv) sufficiency of the quantity of essential drugs dispensed, (v) dispensing of essential drugs by assigned persons, were considered. Each attribute was given a score of 1 if it was satisfied and a score of 0 if the attribute was not satisfied. Then the total score for each CC regarding drug supply services was calculated. Finally, the CCs were graded as per given criteria based on the total score.

It was found that the situation was discouraging as only 40.6% CCs were graded as ‘good’ whereas about one-third (31.3%) were just ‘average’ and as high as about one-third (28.1%) were rated as ‘poor’.

3.7. Availability of furniture and logistics at CCs

The stock of furniture/logistics, including (i) labor table, (ii) investigation table, (iii) steel almirah with two compartments, (iv) back-rest bench (for 4–5 persons), (v) mat/cushion bed for service receiver, (vi) blackboard with stand, (vii) wooden/plastic chair (viii) table with drawer, (ix) patients' register, (x) report card, (xi) care providers’ attendance book, (xii) laptop computer (xiii) Internet facility (with Modem), was investigated. Each furniture/logistics was assigned a score in the following way:

Score = 2 if supply was sufficient and condition was good; score = 1 if supply was insufficient but condition was good or supply was sufficient and condition was not good; score = 0 if supply was insufficient and condition was not good. The total score for the availability of furniture/logistics for each CC was calculated and, accordingly, the CCs were graded as ‘poor’, ‘average’, and ‘good’. Less than two-thirds (62.5%) of the CCs were in ‘good’ category, 25.0% were in ‘average’ and 12.5% were in ‘poor’ category.

3.8. Quality of health services provided by CCs

The state of health services provided by the CCs was investigated in this study for (i) reproductive and FP services; (ii) integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI); (iii) maternal and neonatal healthcare; (iv) EPI and ARI; (v) nutrition education and micronutrient supplements; (vi) health and family planning education and counseling; (vii) communicable disease control (viii) identification of emergency and complicated cases with referral to higher facilities for better management; (ix) screening for non-communicable diseases, like-hypertension, diabetes, arsenicosis, cancer, heart diseases, and autism; (x) conduction of normal delivery; (xi) treatment for minor ailments and first-aid for simple injuries and handling of emergency cases, like poisoning, snake-bite, burn, etc.; (xii) establishing effective referral linkage with higher facilities (xiii) establishing effective MIS and database of the community; and (xiv) other services under the Essential Service Package of the Government of Bangladesh.

Each service was given a score 1 if it was provided, and score 0 if it was not provided. Then the total score for each CC regarding health services was calculated. Finally, the CCs were graded as per given criteria based on the total score.

Majority (78.1%) of the CCs were graded as ‘good’ in respect of the provision of health services as required by the people while 21.9% CCs were graded as ‘average’.

3.9. Quality of health education services of CCs

The issues covered in the health education services to the community members included: (i) antenatal care (ANC), (ii) delivery plan, (iii) postnatal care (PNC), (iv) child health, (v) growth monitoring of children, (vi) common health problems, (vii) family planning, and (viii) nutrition.

Each issue was given a score 1 if it was covered, and score 0 if it was not covered. The total score for each CC regarding health education was calculated and, accordingly, the CCs were graded based on the total score. Almost all (96.9%) of the CCs were graded as ‘good’ as far as providing health education was concerned, and only 1 CC (3.1%) was graded as ‘average’.

3.10. Community participation in utilization of CC services and community satisfaction

3.10.1. Community participation through utilization of CC services (last five years)

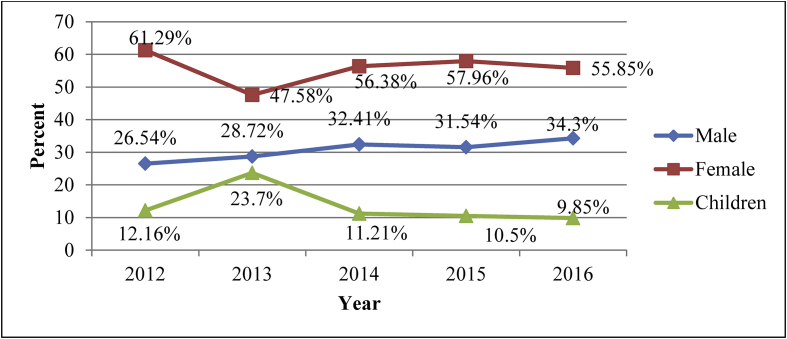

Figure 1 shows the number of patients who utilized CC services during the last five years. It was found that the number of patients utilizing CC services increased over the years. Females used the services more than males and the children.

Figure 1.

Number of patients utilizing CC services during the last five years.

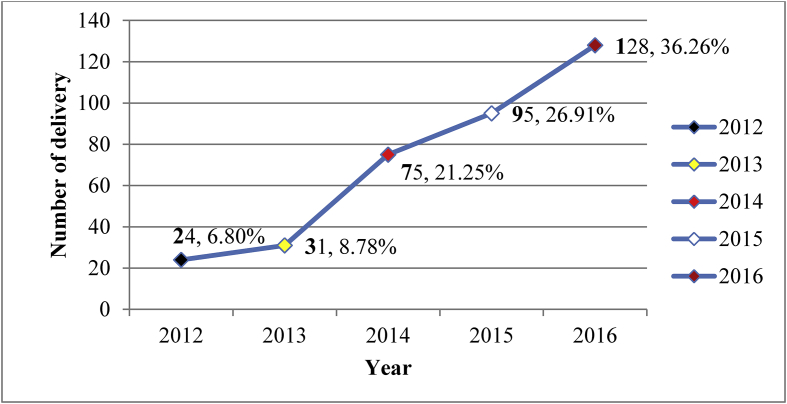

Community participation in utilization of CC services by child delivery (last five years).

Figure 2 reveals information regarding the number of normal deliveries conducted at the CCs during the last five years. It was found that the number of normal deliveries has increased over time-from 24 in 2012 to 128 in 2016.

Figure 2.

Number of normal deliveries conducted at CCs during the last five years.

In this study, attempt was made to quantify the level of satisfaction by assigning score to different levels of satisfaction about each service: Score = 2 if satisfied, Score = 1 if partially satisfied, Score = 0 if not satisfied. So the total score for all 11 services given by a patient ranged from 22 to 0. Level of patient satisfaction about CC services was graded as 18–22: Good, 11–17: Average, ≤10 = Poor.

Table 6 shows that most of the service-users were satisfied with prompt services (85.7%), waiting arrangement (85.7%), qualifications of the service providers (85.6%), interactions and behavior of the care providers (85.3%), and the quality of health education (84.4). They were least satisfied with the arrangement of privacy (72.9%).

Table 6.

Level of user satisfaction over CC services and facilities (n=2,238).

| Services and facilities | Satisfied f (%) | Partially satisfied f (%) | Not satisfied f (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waiting arrangement | 1918 (85.7) | 297 (13.3) | 23 (1.0) |

| Waiting time | 1719 (76.8) | 486 (21.7) | 33 (1.5) |

| Cleanliness of the CC | 1798 (80.3) | 410 (18.3) | 30 (1.3) |

| Privacy maintained | 1631 (72.9) | 535 (23.9) | 72 (3.2) |

| Interaction and behavior of care providers | 1908 (85.3) | 320 (14.3) | 10 (0.4) |

| Perceived quality of services | 1805 (80.7) | 401 (17.9) | 32 (1.4) |

| Availability of medicines | 1707 (76.3) | 477 (21.3) | 54 (2.4) |

| Qualified person(s) provide service | 1916 (85.6) | 285 (12.7) | 37 (1.7) |

| Enough information was given | 1714 (76.6) | 475 (21.2) | 49 (2.2) |

| Received prompt service | 1919 (85.7) | 268 (12) | 51 (2.3) |

| Quality of health education | 1889 (84.4) | 276 (12.3) | 73 (3.3) |

4. Discussion

Community clinics were designed in a way that each can provide health services to around 6,000 rural people, and it was envisaged that their appropriate locations would make them accessible for more than 80% of the population within less than 30-minute walking distance. The infrastructure is simple—two rooms with drinking-water and lavatory facilities under a covered waiting area.

The study revealed that most of the sampled CCs (96.9%) had the government-approved size (450 sq. ft); only 1 CC was smaller than the approved size. More than four-fifths of the CCs under study had two rooms, and the rest (18.8%) had three rooms. Quality of construction of the CCs, on an average, was good. Quality of doors was good in almost all CCs (96.9%), Quality of windows was good in slightly more than four-fifths of the CCs (81.3%) but the quality of roofs was good in less than two-thirds of the CCs (62.5%). Land for all the CCs was donated by local community and in most cases (96.8%) community support groups are actively involved in maintenance of CCs. But in many cases, the quality of construction was below the necessary standard, and the buildings were already showing signs of dilapidation. In 38% of the community clinics, windows and doors were found broken and, in 25% CCs, the roofs had leaks. Seven CCs were in very bad condition within 6–12 months after construction. All these findings indicate that though the government of Bangladesh adopts the concept of public-private partnership but the maintenance issue is still mot up to the mark.

According to the government guidelines11, every CC should have two latrines—one for the males and the other for females. Very few of the sampled CCs met this standard, with many (68.8%) having only one latrine. Half of the latrines were in poor condition (dirty). Less than one-third (31.3%) had tube wells for safe drinking-water. Alarmingly, half of the latrines were dirty which posed a threat to healthy environment.

Almost all CCs (93.75%) had waiting space for patients, well-furnished with benches and other seating facilities. In only 2 CCs, patients had to remain standing. Only 18 (56.3%) of the CCs were found to have electric connection. The findings also show that very few (21.88%) CCs had active hotline telecommunication system.

The essential equipment required to be available at each CC as per government guidelines [11] are listed under the `Results' section. The study found that none of the CCs had the full set of equipment available. However, more than four-fifths of the CCs were found to function with adequate number of primary medical kits (87.5%). When categorized in terms of adequacy and condition (good or bad), the aggregate picture of the availability of equipment in sufficient quantity and good condition was not encouraging. Only 4 CCs (12.5%) were in ‘good’ category, more than four-fifths (81.3%) were in ‘average’ and 6.3% were in ‘poor’ category. In terms of the availability of furniture/logistics, nearly two-thirds of CCs 62.5% were rated to be in ‘good’ category, 25.0% were ‘average’ and 12.5%were in ‘poor’ category. Findings from another study [13] show that none of the CCs surveyed received all the scheduled categories of mentioned equipments.

The study tried to find the number of patients utilizing CC services during the last five years preceding the survey year. It was found that the number of patient utilizing CC services increased over the years. Such as, the number of normal delivery conducted at the CC during the last five years was determined. It was found that the number of normal delivery conducted at the CC increased over time – from 24 in 2012 to 128 in 2016. This finding indicated that community people are being more aware of utilization of services.

The present study attempted to find the level of satisfaction of the service users about the quality of CC services and facilities. Overall it was good; out of 11 criteria more than 80% users were satisfied with 7 criteria: waiting arrangement, cleanliness of the CC, perceived quality of services, interaction and behavior of provider, qualified person providing service, receiving prompt service, and, quality of health education. About 75.0% users were satisfied the remaining 4 service quality categories – waiting time, maintaining privacy, Availability of medicine, and, access to information. Above mention findings indicated that though the quality of CCs were not encouraging, but the user's satisfaction was up to the mark. It may be due to the fact that, in a low-middle income country, like Bangladesh, peoples' expectation for the services was very low, which was fulfilled by the CCs.

The present study revealed that community participation in establishment, management, maintenance and utilization of community clinic is contributory and satisfactory to some extent. But considering the increasing workload on the service providers, creation of more core positions for the community groups, creation of posts for the service providers along with strengthening of domiciliary services of the CC staffs are needed.

As stated earlier, the activities of CCs remained closed from 2001 to 2008 due to a change in the Government. After another change with the previous political party taking over power, the CCs were again made functional since 2009 under a project titled “Revitalization of Community Healthcare Initiatives in Bangladesh (RCHCIB)." [11] At this phase, several international agencies, such as WHO, JICA, Gavi The Vaccine Alliance, UNICEF, USAID, TIKA, OMRON, Save the Children and some NGOs [14] came up with financial and technical assistance for training of service providers, repair and construction of more CCs, and ensuring availability of drugs and equipment. This will lead to remarkable improvements of the CCs and of health indicators among the rural populace.

5. Conclusion

In spite of some limitations in the provision of healthcare services, community clinics have emerged as a flagship programme of the Government of Bangladesh aiming at making health services available at the doorstep of rural people. Mobility of rural people has increased for seeking essential treatment from community clinics. Availability of basic healthcare services at their doorsteps and referrals of complicated cases to the higher-level facilities have been possible due to establishment of these tiny, grassroots-level health facilities. Health education and counselling through CCs have created mass awareness of many health problems and of the necessity of seeking care from the formal health professionals instead of the quacks and traditional healers. To ensure effective health care provision, further improvements of CCs is essential. This could be possible through infrastructure development, employment of more skilled health personnel, adequate supply of essential drugs and logistics, proper supervision and monitoring. To make it successful revolutionise the attempt of public-private partnership thorough effective community participation in operating community health facilities is inevitable.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

B.K. Riaz: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

L. Ali: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

S.A. Ahmad and K.R. Ahmed: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

M.Z. Islam: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

S. Hossain: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Chu C. 2016. Chapter 20 community participation in public Health : definitions and conceptual framework; p. 232. August), 20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Bangladesh; Dhaka: 1998. Health and Population Sector Program 1998-2003, Program Implementation Plan, Part 1 and II. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO/UNICEF . 1978. Alma Ata, Primary HealthE Care. Report of the International Conference on Primary HealthCare, Alma Ata, USSR 6-12 September. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke D., Doerr S., Hunter M., Schmets G., Paviza A. 2019. The Private Sector and Universal Health Coverage; pp. 434–435. (April) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.E Baum Frances, Bush Robert A., Modra Carolyn C., Charlie J., Murray Epidemiology of participation: an Australian community study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2000;54:414–423. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.6.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Qingwen. Community participation in urban China: identifying mobilization factors. Nonprofit Voluntary Sect. Q. December 1, 2007;36(4):622–642. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahriar Ahsan, Routh Subrata, Bhuiyanet al Mohammed Ali. Operations Research Project Working Paper No. 129. 1999. Operationalization of ESP delivery and community clinics. Behaviour change communication needs of community clinics: a study of providers perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helfenbein S., Sayeed A. 2000. Increasing Community Participation. http://www.ERC-CHS/Com.participation.htlm. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Ministry of Health and Fmily Welfare. Health, Nutrition and Population Sector Program. HNPSP); 2003. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Health Population Nutrition Sector Development Program (HPNSDP); 2011. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revitalization of Community Health Care Initiatives in Bangladesh (RCHCIB) Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Bangladesh: March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) 2015. Health bulletin Dhaka, Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Normand C., Iftekar M.H., Rahman S.A. quality and utilization of services; 2002. Assessment of the Community Clinics: Effects on Service Delivery. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Community Clinic News Letter; 2017. Community based health care (CBHC)http://communityclinic.gov.bd/index.php/infrastructure?id=35 Available at: 2016. [Google Scholar]